Abstract

Gemin3 is a DEAD-box RNA helicase that binds to the Survival of Motor Neurons (SMN) protein and is a component of the SMN complex, which also comprises SMN, Gemin2, Gemin4, Gemin5, and Gemin6. Reduction in SMN protein results in Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a common neurodegenerative disease. The SMN complex has critical functions in the assembly/restructuring of diverse ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. Here we report that Gemin3 and Gemin4 are also in a separate complex that contains eIF2C2, a member of the Argonaute protein family. This novel complex is a large ∼15S RNP that contains numerous microRNAs (miRNAs). We describe 40 miRNAs, a few of which are identical to recently described human miRNAs, a class of small endogenous RNAs. The genomic sequences predict that miRNAs are likely to be derived from larger precursors that have the capacity to form stem–loop structures.

Keywords: MicroRNA, RNP, Gemin3, Argonaute, SMN, SMA

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a common, autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disease caused by deletions or loss-of-function mutations of the Survival of Motor Neurons (SMN) protein (Melki 1997). The SMN protein is in a complex with five proteins known as Gemin2 (formerly SIP1; Liu et al. 1997), Gemin3 (a DEAD-box putative RNA helicase; Charroux et al. 1999), Gemin4 (Charroux et al. 2000), Gemin5 (Meister et al. 2001; Gubitz et al. 2002), and Gemin6 (Pellizzoni et al. 2002). The SMN complex plays important roles in the assembly/restructuring and function of diverse ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes, including spliceosomal small nuclear RNPs (snRNPs; Fischer et al. 1997; Pellizzoni et al. 1998; Meister et al. 2001), small nucleolar RNPs (snoRNPs; Jones et al. 2001; Pellizzoni et al. 2001a) heterogeneous nuclear RNPs (hnRNPs; Mourelatos et al. 2001), and transcriptosomes (Pellizzoni et al. 2001b).

eIF2C (eukaryotic initiation factor 2C), a protein of unknown biochemical function, is a member of a large family of proteins known as Argonaute proteins (Grishok et al. 2001; Kataoka et al. 2001). Argonaute proteins contain two conserved domains of unknown function known as the PAZ and PIWI domains (Grishok et al. 2001; Kataoka et al. 2001). Genetic studies indicate a role for Argonaute family members in two important pathways of gene regulation: RNA interference (RNAi) and developmental regulation by the two small temporal RNAs (stRNAs) lin-4 and let-7 (Lee et al. 1993; Reinhart et al. 2000). In RNAi, small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) of 21–23 nt recognize homologous mRNAs and silence gene expression by degradation of the mRNA (Fire et al. 1998; Bass 2000; Zamore et al. 2000; Elbashir et al. 2001; Sharp 2001). In contrast, stRNAs, also of ∼22 nt, recognize complementary sequences in the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of target mRNAs and prevent the accumulation of nascent polypeptides (Lee et al. 1993; Reinhart et al. 2000). In Caenorhabditis elegans, the Argonaute family member rde-1 was shown to be essential for RNAi (Tabara et al. 1999), whereas alg-1 and alg-2 are required for the maturation and activity of stRNAs (Grishok et al. 2001). Although these pathways are distinct, both require cleavage of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) precursors by the nuclease Dicer to generate siRNAs or stRNAs (Bernstein et al. 2001; Grishok et al. 2001; Hutvagner et al. 2001; Ketting et al. 2001; Knight and Bass 2001). siRNAs were shown to assemble in an ∼500-kD complex termed RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex; Hammond et al. 2000). This complex contains the active species that subsequently recognize homologous mRNAs and guide their cleavage by an unidentified nuclease(s) present in RISC. Interestingly, Argonaute2, a Drosophila protein, was found to be part of the RISC nuclease and to copurify with siRNAs (Hammond et al. 2001). RNAi is evolutionary conserved. A similar siRNA-mediated mechanism of gene silencing known as posttranscriptional gene silencing (PTGS) in plants (Hamilton and Baulcombe 1999; Vance and Vaucheret 2001) and quelling in Neurospora Crassa (Romano and Macino 1992) also requires the Argonaute proteins AGO1 (Fagard et al. 2000) and QDE-2 (Catalanotto et al. 2000), respectively. In Drosophila, another Argonaute protein, Aubergine, is required both for silencing of the repetitive Stellate locus via an RNAi-like mechanism (Aravin et al. 2001) and for proper posterior body patterning (Harris and Macdonald 2001). The stRNAs are initially transcribed as ∼75-nt precursors that are predicted to form stem–loop structures. The mature 22-nt stRNA sequences are found in one of the strands of the double-stranded stems of the precursors and are released by the action of Dicer (Hutvagner et al. 2001; Ketting et al. 2001). These observations gave rise to speculation that Argonaute family members may function in association with siRNAs, stRNAs, and possibly other, as yet unidentified, small RNA cofactors to regulate their maturation and activity. However, a physical interaction between Argonaute proteins and stRNAs or other small endogenous RNAs has not been shown.

Here we report the identification of a novel RNP that sediments as an ∼15S particle on sucrose gradients and contains Gemin3, Gemin4, and human eIF2C2 along with numerous very small, cellular, ∼22-nt RNAs (microRNAs, miRNAs). We identify 40 miRNAs, only a few of which are identical to human miRNAs, a recently described class of small endogenous RNAs (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001). The genomic sequences predict that miRNAs are likely to be derived from larger precursors that have the capacity to form stem–loop structures.

Results

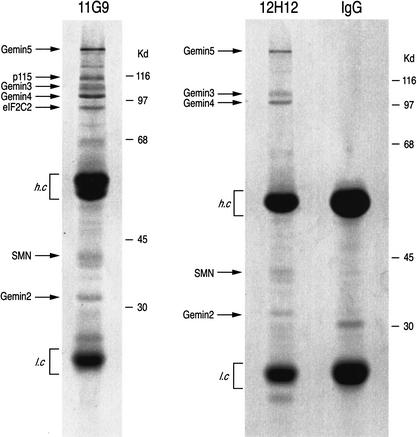

Gemin3 is in a complex with eIF2C2 in vivo

To better understand the physiological role of Gemin3, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed to identify novel, putative Gemin3 RNA target(s) and protein cofactors. The two specific monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against Gemin3, 11G9 and 12H12 (Charroux et al. 1999), were used to characterize Gemin3-associated components in HeLa cell lysates, and nonimmune mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) served as a negative control. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by staining with Coomassie blue. As shown in Figure 1, both 11G9 and 12H12 immunoprecipitated Gemin3 and all other known components of the SMN complex, including SMN, Gemin2, Gemin4, and Gemin5 (Meister et al. 2001; Gubitz et al. 2002). Two additional proteins with apparent molecular masses of ∼115 kD and ∼95 kD were immunoprecipitated with 11G9. These proteins were excised from the gel and microsequenced using nanoelectrospray mass spectrometry (Pandey and Mann 2000). The 95-kD protein was found to be human eIF2C2 (accession no. AY077717). The 115-kD protein will be described elsewhere.

Figure 1.

Gemin3 is in a complex with eIF2C2 in vivo. Immunoprecipitations were performed with monoclonal antibodies 11G9 or 12H12 against Gemin3 or with nonimmune mouse IgG from total HeLa cell lysates. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. The identity of immunoprecipitated proteins is shown on the left. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the right; (h.c) heavy chain of the antibody; (l.c) light chain of the antibody.

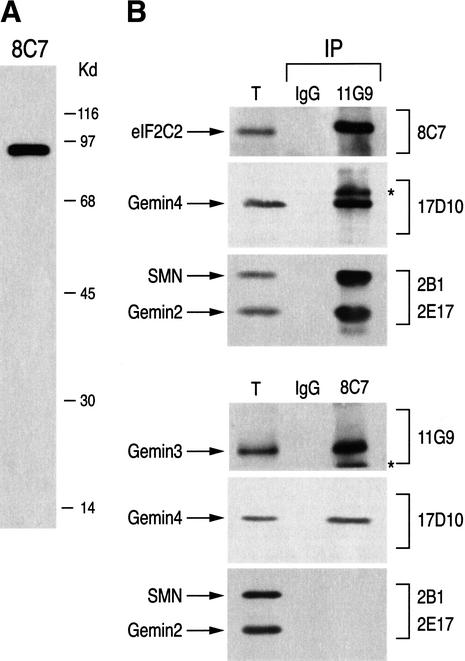

Gemin3 and Gemin4 associate with eIF2C2 in vivo and in vitro

The majority of Gemin3 and Gemin4 proteins are found in the SMN complex; however, a less abundant Gemin3–Gemin4 complex, separate from the SMN complex, has also been found (Charroux et al. 2000). To further investigate the interaction between eIF2C2 and Gemin3, we produced a monoclonal antibody to eIF2C2, designated 8C7. 8C7 recognizes a single band of the expected ∼95 kD on a Western blot of total HeLa cell extract (Fig. 2A) and specifically immunoprecipitates in vitro translated eIF2C2 under stringent conditions (data not shown). We next carried out immunoprecipitations from HeLa cell lysates using 8C7 or the anti-Gemin3 antibody 11G9. The immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting with 8C7, 11G9, and with 17D10 against Gemin4, 2B1 against SMN, and 2E17 against Gemin2. Nonimmune mouse IgG was used as negative control. As shown in Figure 2B, Gemin3, Gemin4, and eIF2C2 coimmunoprecipitated, indicating that they are associated in a complex in vivo, whereas SMN and Gemin2 coimmunoprecipitated only with Gemin3. Because the anti-eIF2C2 antibody 8C7 did not coimmunoprecipitate SMN or Gemin2 (Fig. 2B) and antibodies to SMN or Gemin2 did not coimmunoprecipitate eIF2C2 (data not shown), the Gemin3–Gemin4–eIF2C2 complex must be different and separate from the SMN complex. To investigate whether eIF2C2, Gemin3, and Gemin4 interact with each other, we performed in vitro binding experiments. In these experiments recombinant glutathione S-tranferase–eIF2C2 fusion protein (GST–eIF2C2) or GST was immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads and incubated with [35S]methionine-labeled proteins produced by in vitro transcription and translation in rabbit reticulocyte lysate. To exclude the possibility of nucleic acid-mediated interactions, all in vitro translated products were treated with DNase I and RNase A prior to bindings. As shown in Figure 2C, Gemin3 and Gemin4, but not SMN or Gemin2, bind to GST–eIF2C2. No binding of these proteins to GST alone was detected (data not shown). Similarly, in vitro translated eIF2C2 binds efficiently to recombinant GST–Gemin3 and GST–Gemin4, but not to GST alone (Fig. 2D). Thus, Gemin3 and Gemin4 interact with eIF2C2, although we cannot exclude the possibility that other proteins present in the reticulocyte lysate mediate or stabilize this interaction.

Figure 2.

Gemin3 and Gemin4 associate with eIF2C2 in vivo and in vitro. (A) 8C7 recognizes a single band at ∼95 kD corresponding to eIF2C2, on Western blot of total HeLa cell lysate. Molecular mass markers (in kilodaltons) are shown on the right. (B) Immunoprecipitations (IP) were performed from total HeLa cell lysates with antibodies against Gemin3 (11G9), eIF2C2 (8C7), or nonimmune mouse IgG as negative control. The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with monoclonal antibodies 8C7, 11G9, 17D10 (anti-Gemin4), 2B1 (anti-SMN), and 2E17 (anti-Gemin2) as indicated. Total (T) shows ∼3% of the input used for IPs. (*) Undissociated heavy and light chains of the antibodies used for IPs. (C,D) The indicated proteins were produced by in vitro transcription and translation in reticulocyte lysate, labeled with [35S]methionine, and incubated with recombinant GST–eIF2C2 (C) or GST–Gemin3, GST–Gemin4, and GST (D); bound proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by fluorography. Total refers to 10% of the input fraction used for binding.

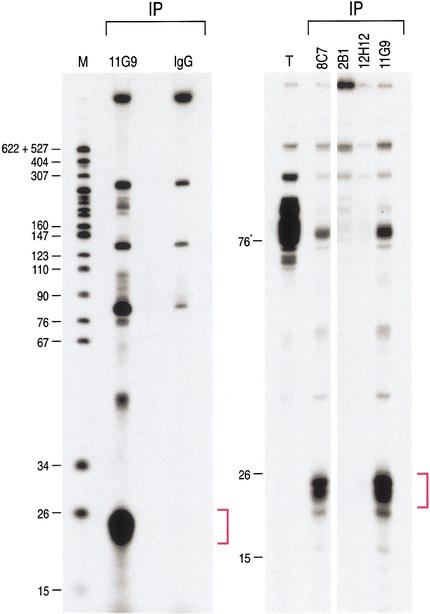

Gemin3–eIF2C2 complexes contain ∼22-nt microRNAs

We next wished to determine whether RNA(s) are found in the Gemin3–eIF2C2 complex in vivo. For this, we performed immunoprecipitations from HeLa cell lysate with the anti-Gemin3 mAb 11G9 and with the anti-eIF2C2 mAb 8C7. To assess the specificity of the interactions, immunoprecipitations were also carried out with 12H12, the antibody that recognizes the pool of Gemin3 that associates only with the SMN complex, with mAb 2B1 against SMN, and with the nonimmune mouse IgG. Immunoprecipitates were digested with proteinase K, and RNAs were isolated, 3′-end-labeled with [5′-32P]-pCp, and resolved by electrophoresis on 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gels. As shown in Figure 3, a major RNA band migrating at ∼22 nt was immunoprecipitated with mAb 11G9 and with mAb 8C7 but not with the other antibodies. The size of these RNAs suggested that they may represent the mature forms of endogenous, stRNA-like RNAs. For consistency with other designations (see below), we refer to these very small RNAs here as microRNAs (miRNAs) and to the corresponding RNPs as miRNPs. These experiments show that miRNAs specifically associate with Gemin3–eIF2C2 complexes.

Figure 3.

∼22-nt RNAs (miRNAs) are in a complex with Gemin3 and eIF2C2 in vivo. Immunoprecipitations were performed with 11G9 (anti-Gemin3), nonimmune mouse IgG, 8C7 (anti-eIF2C2), 2B1 (anti-SMN), and 12H12 (anti-Gemin3) from total HeLa cell lysates. RNA was isolated, 3′-end-labeled with [5′-32P]-pCp, and resolved by electrophoresis on 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Total (T) shows RNA representing ∼3% of the input used for immunoprecipitations (IPs). The lane marked M contains 32P-labeled pBR322/MspI digest as size marker; nucleotide sizes are indicated on the left.

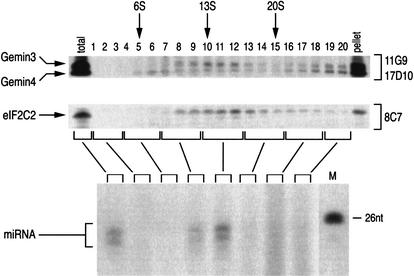

Gemin3, Gemin4, eIF2C2, and miRNAs are in ∼15S RNPs

To further characterize the Gemin3–Gemin4–eIF2C2–miRNA complex, we analyzed HeLa cell lysate by sedimentation on sucrose gradients. The sucrose gradients were then fractionated and their proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE; the presence of Gemin3, Gemin4, and eIF2C2 in each fraction was determined by immunoblotting using antibodies 11G9, 17D10, and 8C7, respectively. The data, presented in Figure 4, show that Gemin3, Gemin4, and eIF2C2 cosediment with a peak at ∼15S. Most of the Gemin3 and Gemin4 proteins are found in the pellet, which is consistent with their presence in SMN complexes that sediment under the same conditions mostly as larger particles of >20S (data not shown). In contrast, most of the eIF2C2 protein is found in the 15S peak with only a small fraction at the bottom of the gradient. To determine if these Gemin3–Gemin4–eIF2C2 particles also contain the miRNAs, immunoprecipitations with 11G9 were carried out from pooled fractions, and the coimmunoprecipitated RNAs were identified by labeling with [5′-32P]-pCp followed by electrophoresis on 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gels. As shown in Figure 4, ∼22-nt miRNAs cosediment with the peak of the Gemin3–Gemin4–eIF2C2 particles. These experiments thus provide physical evidence that Gemin3, Gemin4, eIF2C2, and miRNAs form large novel RNPs that sediment at ∼15S.

Figure 4.

miRNPs sediment on sucrose gradients as ∼15S particles. Total HeLa cell lysate was sedimented on a 5%–20% sucrose gradient. Fractions were collected (indicated by numbers), resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblotting with 11G9 (anti-Gemin3), 17D10 (anti-Gemin4), and 8C7 (anti-eIF2C2). Total lane shows ∼5% of input used for gradient analysis; lane marked pellet shows ∼5% of the pellet from the gradient. (Bottom panel) fractions were pooled (indicated by brackets) and used for immunoprecipitations with 11G9. RNA was isolated, 3′-end-labeled with [5′-32P]-pCp, and resolved by electrophoresis on a 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. Nucleotide size marker (M) is shown on the right. S-values are shown.

Numerous miRNAs, derived from novel genes, associate with the Gemin3–Gemin4–eIF2C2 complex

To identify the small RNAs that associate with the Gemin3–Gemin4–eIF2C2 particle, we directionally cloned the ∼22-nt RNAs present in the 11G9 immunoprecipitates using a previously described method (Elbashir et al. 2001). Of the ∼200 independent isolates that were sequenced, ∼50% contained inserts, which are presented in Table 1. We identified 40 different miRNAs ranging in size from 16 nt to 24 nt. BLAST searches against human genomic sequences revealed the chromosomal localization and flanking sequences for 25 miRNAs (Table 1). One miRNA (miR-22) was represented in the EST database, but no gene locus was found. Two miRNAs (miR-106 and miR-107) were identified by their homology to miR-91 and miR-103, respectively, although we do not know if they are, indeed, present in Gemin3–eIF2C2 RNPs. These miRNAs and flanking genomic sequences are predicted to fold into stem–loop structures similar to the precursors of stRNAs (Fig. 5A). By analogy to the maturation of stRNAs, it seems very likely that the mature ∼22-nt miRNAs are processed from longer stem–loop precursors by an RNAi-like mechanism. Several of the putative miRNA precursors are found in the genome as clusters (Fig. 5B), whereas others are present as copies in the same or different chromosomes (Table 1). There was no database entry for 19 of the miRNAs (Table 1), possibly because they correspond to areas of the human genome that have not been sequenced. None of the miRNAs represented fragments of mRNAs or other known RNAs, such as snRNAs or snoRNAs. While this manuscript was in the final stages of preparation, three groups reported the identification of several stRNA-like, small RNAs that they named microRNAs (miRNAs), by cloning ∼22-nt RNAs from C. elegans (Lee and Ambros 2001; Nelson et al. 2001), D. melanogaster, and HeLa cells (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001). Lagos-Quintana et al. (2001) identified 21 novel miRNAs from HeLa cells, 9 of which are identical to the miRNAs described here (Table 1). Our findings confirm the existence of a large class of small RNAs (miRNAs) with probable regulatory roles, and identify 31 novel miRNAs (Table 1). Importantly, we provide evidence for the existence of a novel class of RNPs containing Gemin3, Gemin4, eIF2C2, and miRNAs. It is interesting to note that there is only a small overlap between the miRNAs that we identified and the human miRNAs reported (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001). This suggests that the number of miRNAs is much higher than so far appreciated. Because the miRNAs were directionally cloned, their 5′ to 3′ polarity was preserved and showed that the miRNAs associated with Gemin3–eIF2C2 were present in a single-stranded form, as there was no case in which the complementary strand of the miRNAs was identified. This result is analogous to what was found for mature stRNAs and miRNAs and unlike the siRNAs that include both strands. The presence of the same miRNAs in the 11G9 and 8C7 immunoprecipitates as well as their expression in HeLa cells was confirmed by Northern blots (data not shown).

Table 1.

Human microRNAs

| miRNA

|

Number of clones

|

miRNA sequence

|

Size (nt)

|

Chromosome

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-91 | 2 | CAAAGUGCUUACAGUGCAGGUAGU | 24 | 13 |

| miR-18 | 1 | UAAGGUGCAUCUAGUGCAGAU | 21 | 13 |

| miR-19a | 1 | UGUGCAAAUCUAUGCAAAACUGA | 23 | 13 |

| miR-19b | 11 | UGUGCAAAUCCAUGCAAAACUGA | 23 | 13, X |

| miR-92 | 3 | UAUUGCACUUGUCCCGGCCUGU | 22 | 13, X |

| miR-93 | 1 | AAAGUGCUGUUCGUGCAGGUAG | 22 | 7 (twice) |

| miR-94 | 1 | AAAGUGCUGACAGUGCAGAU | 20 | 7 |

| miR-23 | 6 | AUCACAUUGCCAGGGAUUUCCA | 22 | 19 |

| miR-21 | 23 | UAGCUUAUCAGACUGAUGUUGAC | 23 | 17 |

| miR-95 | 1 | UUCAACGGGUAUUUAUUGAGCA | 22 | 4 |

| miR-96 | 4 | UUUGGCACUAGCACAUUUUUGC | 22 | 7 |

| miR-97 | 2 | UGUAAACAUCCUCGACUGGAAGC | 23 | 6 |

| miR-98 | 1 | UGAGGUAGUAAGUUGUAUUGUU | 22 | X |

| miR-99 | 1 | AACCCGUAGAUCCGAUCUUGUG | 22 | 21 |

| miR-27 | 3 | UUCACAGUGGCUAAGUUCC | 19 | 19 |

| miR-100 | 1 | AACCCGUAGAUCCGAACUUGUG | 22 | 11 |

| miR-101 | 1 | UACAGUACUGUGAUAACUGAAG | 22 | 1, 9 |

| miR-102 | 2 | UAGCACCAUUUGAAAUCAGU | 20 | 1, 7 (twice) |

| miR-24 | 2 | UGGCUCAGUUCAGCAGGAACAG | 22 | 9, 19 |

| miR-103 | 1 | AGCAGCAUUGUACAGGGCUAUGA | 23 | 5, 20 |

| miR-104 | 2 | UCAACAUCAGUCUGAUAAGCUA | 22 | 17 |

| miR-105 | 3 | UCAAAUGCUCAGACUCCUGU | 20 | X (twice) |

| miR-16 | 1 | UAGCAGCACGUAAAUAUUGGCG | 22 | 3, 13 |

| miR-106 | — | AAAAGUGCUUACAGUGCAGGUAGC | 24 | X |

| miR-107 | — | AGCAGCAUUGUACAGGGCUAUCA | 23 | 10 |

| miR-108 | 1 | AUAAGGAUUUUUAGGGGCAUU | 21 | — |

| miR-109 | 1 | CUGGUCGAGUCGGCCUGCGC | 20 | — |

| miR-22 | 1 | AAGCUGCCAGUUGAAGAAC | 19 | — |

| miR-110 | 1 | UCGAGCGGCCGACGUCG | 17 | — |

| miR-111 | 1 | UGUGCAAAUCUAUGCAAAACUGU | 23 | — |

| miR-112 | 1 | GGUCCUGACAUCCACGGAA | 19 | — |

| miR-113 | 1 | UCGAGCCCUGGUGCGCCCACCA | 22 | — |

| miR-114 | 1 | UAGCUGCACGUAAAUAUUGGCG | 22 | — |

| miR-115 | 2 | UGAAGCGGAGCUGGAA | 16 | — |

| miR-116 | 2 | UUGAUCCUGGCUCAGGACGAACGCUG | 26 | — |

| miR-117 | 1 | UUCAGCAGGAACAGUU | 16 | — |

| miR-118 | 1 | AUGCCUUGAGUGUAGGAU | 18 | — |

| miR-119 | 1 | AUUGCCAGGGAUUACCAU | 18 | — |

| miR-120 | 1 | GGCGGGACGCAGCGUGU | 17 | — |

| miR-121 | 1 | UGAACCACCUGAUCCCUUCCCGAA | 24 | — |

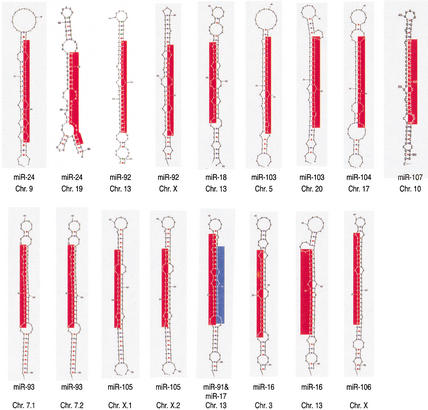

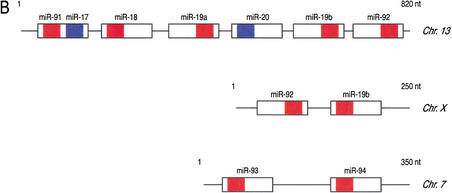

Figure 5.

Predicted secondary structure of putative miRNA precursors and organization of miRNA gene clusters. (A) 70 nt of genomic sequence upsteam and 70 nt downstream of the cloned miRNAs were used to predict the secondary structure of putative miRNA precursors, using the computer program mfold (Mathews et al. 1999). The size of the putative miRNA precursors was then reduced to ∼80 nt, and this sequence was used again for secondary structure prediction by mfold. The putative precursor of miR-91 also contains the sequence of miR-17 on the opposite strand (colored in blue). This finding is similar to the C. elegans miR-56 and miR-56*, which are processed from the same precursor, although only miR-56 is thought to be the functional miRNA (Nelson et al. 2001). Chromosomal location is indicated. Red areas represent mature miRNAs. (B) The putative miRNA precursors are represented as boxes, and the mature miRNAs identified in this study as part of miRNPs are indicated in red. Previously reported miRNAs (Lagos-Quintana et al. 2001) not found in this study are shown in blue. The chromosomal location is indicated on the right. The miRNA cluster on chromosome 13 contains two miRNAs (miR-91 and miR-92) not previously identified; miRNA-91 and miR-17 (colored in blue) are presumably derived from the same precursor. The size of clusters in nucleotides (nt) is shown.

Discussion

Several important conclusions emerge from this study. Gemin3, Gemin4, and eIF2C2 assemble with miRNAs to form novel RNPs (miRNPs). The function of miRNAs is presently unknown, but the discovery of the miRNPs is of considerable significance because RNAs function in cells in the form of RNPs, and the identification of their components is essential for understanding the function of the RNAs with which they are associated. Furthermore, the specific major components of the miRNPs we identified—Gemin3, Gemin4, and eIF2C2—provide intriguing clues and possible connections to the function of miRNAs and pathways with which they may intersect. From the composition of the immunoprecipitations with 11G9 and 8C7, we conclude that there may be a few additional proteins in miRNPs, but Gemin3, Gemin4, and eIF2C2 appear to be the major constituents. By analogy to stRNAs, miRNAs are likely to regulate the expression of other RNAs. The presence of a plethora of miRNAs within miRNPs likely reflects their ability to recognize a wide range of diverse RNA targets, the identification of which will be critical for understanding the function of miRNPs. The finding that eIF2C2 associates with mature miRNAs ties together the genetic studies that show that Argonaute family members are required for the maturation and activity of stRNAs (Grishok et al. 2001) as well as siRNAs (Tabara et al. 1999), and the demonstration that Argonaute2 is part of RISC (Hammond et al. 2001). Moreover, the discovery of Gemin3, a DEAD-box putative RNA helicase in miRNPs, indicates that Gemin3 may mediate RNA unwinding or RNP restructuring events during the maturation of miRNAs and/or in downstream events such as target RNA recognition. Indeed, genetic studies have shown that many putative helicases, such as qde-3 (Cogoni and Macino 1999), SDE3 (Dalmay et al. 2001), mut6 (Wu-Scharf et al. 2000), as well as Dicer, are essential for RNAi, whereas the DEAH-box RNA helicase Spindle-E is required for silencing of the Stellate locus in Drosophila via an RNAi-like mechanism (Aravin et al. 2001). It is possible that Gemin3, Gemin4, and eIF2C2 are common components of all miRNPs, but it is also possible that other miRNPs are comprised, for example, of Gemin3 associated with different members of the Argonaute family and, conversely, that different Argonaute proteins associate with different RNA helicases resulting in miRNPs with different properties. The fact that most of the Gemin3 and Gemin4 proteins are found in the SMN complex (Charroux et al. 1999, 2000) raises the intriguing possibility that the SMN complex, a key factor in the biogenesis and function of diverse RNPs, may intersect with the pathways in which miRNPs function. The binding of Gemin3 to SMN is impaired in SMN mutants found in SMA patients (Charroux et al. 1999). It will be of great interest to determine what effect this has on miRNPs in this devastating neurodegenerative disease and, more generally, what regulates the distribution of Gemin3 and Gemin4 between the SMN complex and miRNPs.

Materials and methods

Identification of human eIF2C2 and plasmid constructs

The 95-kD band present in the 11G9 immunoprecipitate was excised from the gel, digested with trypsin, microsequenced by nanoelectrospray mass spectrometry, and was unambiguously identified as human eIF2C2. eIF2C2 was cloned by RT-PCR from HeLa cell mRNA, and the sequence was deposited in GenBank under accession number AY077717. The primers used to amplify eIF2C2 cDNA were: forward, ATAATAGGATTCCA TGGACATCCCCAAAATTGACATCTATC; reverse, ATATT AGAATTCTCAAGCAAAGTACATGGTGCGCAGAGTGTC. After digestion of the PCR product with BamHI and EcoRI enzymes (NEB), the cDNA was subcloned in the following vectors: pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) for in vitro translations; pGEX-6P-2 (Pharmacia) for production of recombinant protein fused to GST; pet28a (Novagen) for production of His-tag recombinant protein. SMN, Gemin2, Gemin3, and Gemin4 constructs have been described previously (Liu et al. 1997; Charroux et al. 1999, 2000).

Antibodies

mAb 8C7 against eIF2C2 was prepared by immunizing mice with recombinant His-tagged eIF2C2 protein. mAbs 2B1 against SMN, 2E17 against Gemin2, and 11G9 and 12H12 against Gemin3 have been previously described (Charroux et al. 1999).

Immunoprecipitations and cloning of miRNAs

Total HeLa cell lysate was prepared by brief sonication in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 200 mM sodium chloride, 2.5 mM magnesium chloride, and 0.05% NP-40; lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 25,000g for 15 min at 4°C. Binding and washing buffer for the experiments shown in Figures 1 and 3 was the same as the lysis buffer. For Figure 2B, the binding and washing buffer was 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM sodium chloride, 2.5 mM magnesium chloride, and 0.05% NP-40. For RNA immunoprecipitations, lysate from ∼107 cells was used with 40 μg of purified antibody; the immunoprecipitates were treated with DNAse I (0.5 U/μL; Roche) at 30°C for 15 min, followed by Proteinase K digestion (0.2 μg/μL; Roche) at 37°C for 30 min. RNA was extracted with saturated phenol followed by two phenol/chloroform extractions and ethanol precipitation. The RNA was 3′-end-labeled with [5′-32P]-pCp and T4 RNA ligase (NEB). The ∼22-nt miRNAs were cloned by using the protocol developed by Elbashir et al. (2001).

In vitro protein-binding assays

The in vitro protein-binding assays were performed as previously described (Charroux et al. 1999). To exclude nucleic acid-mediated interactions, all in vitro translated products were treated with DNase I (0.5 U/μL) and RNase A (100 μg/mL; Roche) at 30°C for 15 min, prior to bindings.

Sucrose gradient centrifugation

Total HeLa cell lysate, prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 100 mM sodium chloride, and 2.5 mM magnesium chloride buffer, were separated on a 5%–20% sucrose gradient at 33,000 rpm in an SW41 rotor at 4°C for 15 h and 20 min. Fractions (0.5 mL) were collected, and 6% of each fraction was separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting. The remaining fractions were pooled as indicated and used for RNA-immunoprecipitation analysis. The S-values of fractions were estimated according to Osterman (1984).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to members of our laboratory, especially Westley Friesen, Livio Pellizzoni, Nao Kataoka, Amelie Gubitz, Jennifer Baccon, Tracey Golembe, Severine Massenet, and Jeongsik Yong for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript and to Gina Daly for secretarial assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants to G.D. and Z.M., by a grant from the Canadian Institute of Health Research to J.D., and by the Association Française contre les Myopathies (A.F.M.). G.D. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL gdreyfuss@hhmi.upenn.edu; FAX (215) 573-2000.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.974702.

References

- Aravin AA, Naumova NM, Tulin AV, Vagin VV, Rozovsky YM, Gvozdev VA. Double-stranded RNA-mediated silencing of genomic tandem repeats and transposable elements in the D. melanogaster germline. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1017–1027. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass BL. Double-stranded RNA as a template for gene silencing. Cell. 2000;101:235–238. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)71133-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Caudy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a bidentate ribonuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalanotto C, Azzalin G, Macino G, Cogoni C. Gene silencing in worms and fungi. Nature. 2000;404:245. doi: 10.1038/35005169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charroux B, Pellizzoni L, Perkinson RA, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Dreyfuss G. Gemin3: A novel DEAD box protein that interacts with SMN, the spinal muscular atrophy gene product, and is a component of gems. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1181–1194. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.6.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charroux B, Pellizzoni L, Perkinson RA, Yong J, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Dreyfuss G. Gemin4. A novel component of the SMN complex that is found in both gems and nucleoli. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:1177–1186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.6.1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogoni C, Macino G. Posttranscriptional gene silencing in Neurospora by a RecQ DNA helicase. Science. 1999;286:2342–2344. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmay T, Horsefield R, Braunstein TH, Baulcombe DC. SDE3 encodes an RNA helicase required for post-transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2001;20:2069–2078. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.8.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir SM, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. RNA interference is mediated by 21- and 22-nucleotide RNAs. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:188–200. doi: 10.1101/gad.862301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagard M, Boutet S, Morel JB, Bellini C, Vaucheret H. AGO1, QDE-2, and RDE-1 are related proteins required for post-transcriptional gene silencing in plants, quelling in fungi, and RNA interference in animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:11650–11654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200217597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer U, Liu Q, Dreyfuss G. The SMN–SIP1 complex has an essential role in spliceosomal snRNP biogenesis. Cell. 1997;90:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80368-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grishok A, Pasquinelli AE, Conte D, Li N, Parrish S, Ha I, Baillie DL, Fire A, Ruvkun G, Mello CC. Genes and mechanisms related to RNA interference regulate expression of the small temporal RNAs that control C. elegans developmental timing. Cell. 2001;106:23–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00431-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubitz AK, Mourelatos Z, Abel L, Rappsilber J, Mann M, Dreyfuss G. Gemin5: A novel WD repeat protein component of the SMN complex that binds Sm proteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5631–5636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton AJ, Baulcombe DC. A species of small antisense RNA in posttranscriptional gene silencing in plants. Science. 1999;286:950–952. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Bernstein E, Beach D, Hannon GJ. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates post-transcriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature. 2000;404:293–296. doi: 10.1038/35005107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Boettcher S, Caudy AA, Kobayashi R, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2, a link between genetic and biochemical analyses of RNAi. Science. 2001;293:1146–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1064023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AN, Macdonald PM. Aubergine encodes a Drosophila polar granule component required for pole cell formation and related to eIF2C. Development. 2001;128:2823–2832. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Balint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KW, Gorzynski K, Hales CM, Fischer U, Badbanchi F, Terns RM, Terns MP. Direct interaction of the spinal muscular atrophy disease protein smn with the small nucleolar RNA-associated protein fibrillarin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38645–38651. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106161200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka Y, Takeichi M, Uemura T. Developmental roles and molecular characterization of a Drosophila homologue of Arabidopsis Argonaute1, the founder of a novel gene superfamily. Genes Cells. 2001;6:313–325. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketting RF, Fischer SE, Bernstein E, Sijen T, Hannon GJ, Plasterk RH. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:2654–2659. doi: 10.1101/gad.927801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight SW, Bass BL. A role for the RNase III enzyme DCR-1 in RNA interference and germ line development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;293:2269–2271. doi: 10.1126/science.1062039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294:853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Fischer U, Wang F, Dreyfuss G. The spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, SMN, and its associated protein SIP1 are in a complex with spliceosomal snRNP proteins. Cell. 1997;90:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews DH, Sabina J, Zuker M, Turner DH. Expanded sequence dependence of thermodynamic parameters improves prediction of RNA secondary structure. J Mol Biol. 1999;288:911–940. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G, Bühler D, Pillai R, Lottspeich F, Fischer U. A multiprotein complex mediates the ATP-dependent assembly of spliceosomal U snRNPs. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:945–949. doi: 10.1038/ncb1101-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melki J. Spinal muscular atrophy. Curr Opin Neurol. 1997;10:381–385. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199710000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourelatos Z, Abel L, Yong J, Kataoka N, Dreyfuss G. SMN interacts with a novel family of hnRNP and spliceosomal proteins. EMBO J. 2001;20:5443–5452. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CL, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:858–862. doi: 10.1126/science.1065062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterman LA. Methods of protein and nucleic acid research. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A, Mann M. Proteomics to study genes and genomes. Nature. 2000;405:837–846. doi: 10.1038/35015709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni L, Kataoka N, Charroux B, Dreyfuss G. A novel function for SMN, the spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 1998;95:615–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81632-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni L, Baccon J, Charroux B, Dreyfuss G. The survival of motor neurons (SMN) protein interacts with the snoRNP proteins fibrillarin and GAR1. Curr Biol. 2001a;11:1079–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni L, Charroux B, Rappsilber J, Mann M, Dreyfuss G. A functional interaction between the survival motor neuron complex and RNA polymerase II. J Cell Biol. 2001b;152:75–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano N, Macino G. Quelling: Transient inactivation of gene expression in Neurospora crassa by transformation with homologous sequences. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3343–3353. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PA. RNA interference—2001. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:485–490. doi: 10.1101/gad.880001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabara H, Sarkissian M, Kelly WG, Fleenor J, Grishok A, Timmons L, Fire A, Mello CC. The rde-1 gene, RNA interference, and transposon silencing in C. elegans. Cell. 1999;99:123–132. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance V, Vaucheret H. RNA silencing in plants—defense and counterdefense. Science. 2001;292:2277–2280. doi: 10.1126/science.1061334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu-Scharf D, Jeong B, Zhang C, Cerutti H. Transgene and transposon silencing in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by a DEAH-box RNA helicase. Science. 2000;290:1159–1162. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamore PD, Tuschl T, Sharp PA, Bartel DP. RNAi: Double-stranded RNA directs the ATP-dependent cleavage of mRNA at 21 to 23 nucleotide intervals. Cell. 2000;101:25–33. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80620-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]