Abstract

Immunological responsiveness was studied throughout the clinical and histopathological spectrum of leprosy (Ridley–Jopling scale) by the methods of lymphocyte transformation, leucocyte migration inhibition and delayed skin hypersensitivity,

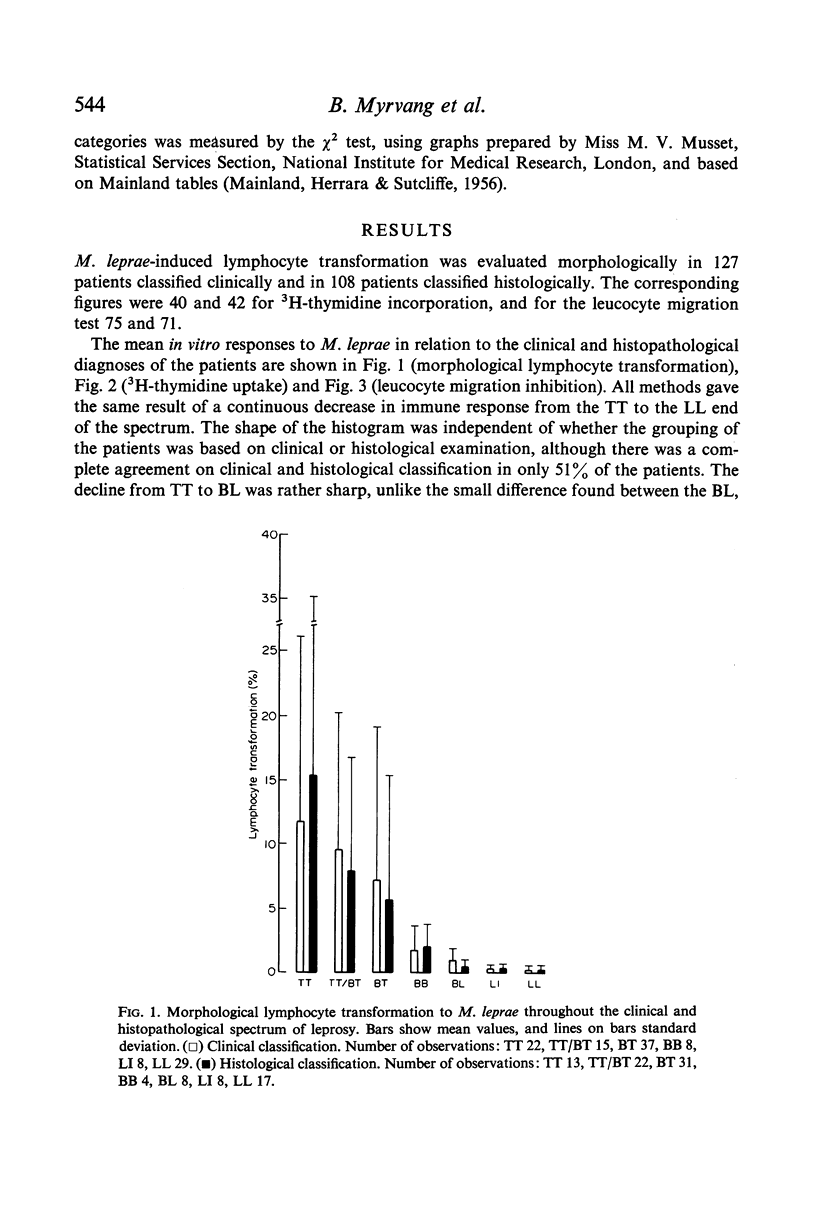

The response to Mycobacterium leprae showed by all methods a continuous decrease from strong responses in the polar tuberculoid (TT) group to virtually negative responses in the polar lepromatous (LL) group. There was a good agreement between the in vitro methods and the lepromin skin test, giving support to the latter as useful tool in the evaluation of immune responsiveness to M. leprae in leprosy patients.

The immune response to BCG and PPD on the other hand, decreased only slightly towards the lepromatous pole of the spectrum, confirming the high degree of specificity of the immune defect in lepromatous leprosy. Patients grouped histologically as subpolar tuberculoid (TT/BT) reacted particularly strongly to BCG and PPD.

As it is likely that the methods used mainly measured T-lymphocyte function, the clinicopathological manifestations of leprosy appear to reflect the strength of the cellular immune response against M. leprae. Thus the findings give strong support to the concept of a host-determined, immunological diseases pectrum as expressed in the Ridley–Jopling classification.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bullock W. E., Jr, Fasal P. Studies of immune mechanisms in leprosy. 3. The role of cellular and humoral factors in impairment of the in vitro immune response. J Immunol. 1971 Apr;106(4):888–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURRIE G. Macular leprosy in Central Africa with special reference to the "maculoid" (dimorphous) form. Int J Lepr. 1961 Oct-Dec;29:473–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaparas S. D., Thor D. E., Godfrey H. P., Baer H., Hedrick S. R. Tuberculin-active carbohydrate that induces inhibition of macrophage migration but not lymphocyte transformation. Science. 1970 Nov 6;170(3958):637–639. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3958.637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estrada-Parra S. Immunochemical identification of a defined antigen of Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun. 1972 Feb;5(2):258–259. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.2.258-259.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federlin K., Maini R. N., Russell A. S., Dumonde D. C. A micro-method for peripheral leucocyte migration in tuberculin sensitivity. J Clin Pathol. 1971 Sep;24(6):533–536. doi: 10.1136/jcp.24.6.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froland S. S., Natvig J. B. Surface-bound immunoglobulin on lymphocytes from normal and immunodeficient humans. Scand J Immunol. 1972;1(1):1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1972.tb03730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröland S. S., Natvig J. B. Effect of polyspecific rabbit anti-immunoglobulin antisera on human lymphocytes in vitro. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1970;39(2-3):121–132. doi: 10.1159/000230341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugas J. M. Enhancing effect of antilymphocytic globulin on human leprosy infection in thymectomized mice. Nature. 1968 Dec 21;220(5173):1246–1248. doi: 10.1038/2201246a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godal T., Myklestad B., Samuel D. R., Myrvang B. Characterization of the cellular immune defect in lepromatous leprosy: a specific lack of circulating Mycobacterium leprae-reactive lymphocytes. Clin Exp Immunol. 1971 Dec;9(6):821–831. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godal T., Myrvang B., Froland S. S., Shao J., Melaku G. Evidence that the mechanism of immunological tolerance ("central failure") is operative in the lack of host resistance in lepromatous leprosy. Scand J Immunol. 1972;1(4):311–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1972.tb03296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godal T., Myrvang B., Samuel D. R., Ross W. F., Lofgren M. Mechanism of "reactions" in borderline tuberculoid (BT) leprosy. A preliminary report. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand Suppl. 1973;236(0):45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godal T., Rees R. J., Lamvik J. O. Lymphocyte-mediated modification of blood-derived macrophage function in vitro; inhibition of growth of intracellular mycobacteria with lymphokines. Clin Exp Immunol. 1971 Apr;8(4):625–637. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jondal M., Holm G., Wigzell H. Surface markers on human T and B lymphocytes. I. A large population of lymphocytes forming nonimmune rosettes with sheep red blood cells. J Exp Med. 1972 Aug 1;136(2):207–215. doi: 10.1084/jem.136.2.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane F. C., Unanue E. R. Requirement of thymus (T) lymphocytes for resistance to listeriosis. J Exp Med. 1972 May 1;135(5):1104–1112. doi: 10.1084/jem.135.5.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner R. A., Glassock R. J., Dixon F. J. The role of anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody in the pathogenesis of human glomerulonephritis. J Exp Med. 1967 Dec 1;126(6):989–1004. doi: 10.1084/jem.126.6.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackaness G. B. The influence of immunologically committed lymphoid cells on macrophage activity in vivo. J Exp Med. 1969 May 1;129(5):973–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.129.5.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milde E. J., Tönder O. Demonstration of rheumatoid factor in tissue by mixed agglutination with tissue sections. Arthritis Rheum. 1968 Aug;11(4):537–545. doi: 10.1002/art.1780110403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees R. J., Waters M. F., Weddell A. G., Palmer E. Experimental lepromatous leprosy. Nature. 1967 Aug 5;215(5101):599–602. doi: 10.1038/215599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees R. J., Weddell A. G., Palmer E., Pearson J. M. Human leprosy in normal mice. Br Med J. 1969 Jul 26;3(5664):216–217. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5664.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley D. S., Jopling W. H. Classification of leprosy according to immunity. A five-group system. Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 1966 Jul-Sep;34(3):255–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley D. S., Waters M. F. Significance of variations within the lepromatous group. Lepr Rev. 1969 Jul;40(3):143–152. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19690026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soborg M., Bendixen G. Human lymphocyte migration as a parameter of hypersensitivity. Acta Med Scand. 1967 Feb;181(2):247–256. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1967.tb07255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soborg M. In vitro detection of cellular hypersensitivity in man. Specific migration inhibition of white blood cells from brucella-positive persons. Acta Med Scand. 1967 Aug;182(2):167–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk J. L., Bryceson A. D. Immunological phenomena in leprosy and related diseases. Adv Immunol. 1971;13:209–266. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk J. L., Waters M. F. Immunological significance of changes in lymph nodes across the leprosy spectrum. Clin Exp Immunol. 1971 Mar;8(3):363–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]