Abstract

Objective:

To compare the perceptions of students and clinical instructors regarding helpful clinical instructor characteristics.

Design and Setting:

We developed a questionnaire containing helpful clinical instructor characteristics for facilitating student learning from a review of the medical and allied health clinical education literature. Respondents rated clinical instructor characteristics from 1 (among the least helpful) to 10 (among the most helpful). Respondents also identified the overall 10 most helpful and 10 least helpful characteristics.

Subjects:

A total of 206 undergraduate students and 46 clinical instructors in the National Athletic Trainers' Association District 4 athletic training education programs accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs responded to the survey.

Measurements:

We computed individual-item and subgroup mean scores for students, clinical instructors, and combined students and instructors. Pearson product moment correlations were computed to evaluate the level of agreement between students and instructors. Correlations were also computed to evaluate the level of agreement between the open-ended responses and the Likert-scale responses.

Results:

Agreement was high between the students' and the clinical instructors' ratings of individual items. Agreement was also high between individual-item means and the directed, open-ended 10 most helpful and 10 least helpful clinical instructor characteristics. Modeling professional behavior was considered the most helpful subgroup of clinical instructor characteristics. Integration of knowledge and research into clinical education was considered the least helpful subgroup of clinical instructor characteristics.

Conclusions:

Clinical instructors should model professional behavior to best facilitate student learning. Integration of research into clinical education may need more emphasis.

Keywords: clinical education, clinical skills, teaching and learning

The National Athletic Trainers' Association (NATA) Education Council has positioned clinical education as one of the most pressing issues of reform in athletic training education.1 One approach to this reform is to qualify the clinical education experience with purposeful objectives rather than chance learning experiences. Many health care professions use clinical education2–6 to reinforce the theoretic information presented in a didactic (classroom) format. This “hands-on” experience has been shown to be valuable in athletic training7–9 and other health care professions such as medicine, nursing, and physical therapy.2,10–15 Clinical education, the integration of theoretic and practical educational components into real-life situations with athletes or patients, should promote and help ensure a positive and constructive learning experience, so that appropriate skills, behaviors, and attitudes for future professional practice are learned and applied.16 Clinical education helps students to learn skills and to apply theoretic knowledge2,10–12; therefore, improving athletic training professional services depends upon maintaining high-quality clinical education. Clinical instructors serve an important role in the facilitation and integration of athletic training knowledge and skills; thus, it is important to identify and promote helpful clinical instructor qualities.

Certified athletic trainers agree that clinical instruction is an important component of athletic training education.9 However, the characteristics that constitute effective clinical instruction in athletic training are not well defined. Therefore, clinical instructors may lack information and direction in instructing students and in improving their own professional development activities.9

Previous researchers7 have identified and described critical helpful and hindering clinical teaching behaviors of supervising athletic trainers, as perceived by student athletic trainers. Yet no athletic training research has compared the responses of both students and clinical instructors regarding helpful teaching characteristics. The purpose of our study was to compare the perceptions of students and clinical instructors of the instructor characteristics that were regarded as the most and least helpful in facilitating student learning.

METHODS

We developed a 49-item, 8-subgroup questionnaire containing helpful clinical instructor characteristics from a review of the medical and allied health clinical education literature.3,4,8,16–21 Only items and subgroups that were validated by the literature to be “helpful” toward student learning were included. The questionnaire was piloted with a convenience sample of 22 students and 7 clinical instructors to gather information about clarity, format, redundancies, and relevance. As a result of the feedback from the pilot study, the 8 subgroups were unchanged; however, 7 individual items were eliminated, leaving a 42-item questionnaire. The subgroups included in the questionnaire were Student Participation (4 items); Clinical Instructor Attitude Toward Teaching (4 items); Problem Solving (5 items); Instructional Strategy (6 items); Humanistic Orientation (6 items); Knowledge and Research (6 items); Modeling (7 items); and Self-Perception (4 items).

Packets with questionnaires, instructions, and postage-paid return envelopes were mailed to all directors of athletic training education programs accredited by the Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs in NATA District 4 (n = 20), excluding Ball State University. Program directors were informed that the study was approved by the institutional review board and that participation was voluntary. We asked that the questionnaires be distributed to clinical instructors and undergraduate student athletic trainers. A clinical instructor was defined as a person who provides direct supervision and instruction to students in the clinical aspect of athletic training education. Graduate assistants were considered clinical instructors if they were classified as such by the program director. Student athletic trainers were defined as students who were formally accepted into the undergraduate athletic training education program and who were deemed by the program director to have an opinion on helpful clinical instructor characteristics.

Respondents were asked to rate each characteristic on a 1 to 10 Likert scale, indicating the characteristic's helpfulness to student learning, with 1 being among the least helpful and 10 being among the most helpful. Each item was scored independently. Respondents were then asked to identify the 10 most helpful and 10 least helpful characteristics overall in a directed, open-ended format. For this section, respondents could choose any of the 42 items from the questionnaire, regardless of their prior rating of helpfulness. This was done to compare the mean ratings of the individual items.

Sixteen (80.0%) of the program directors returned questionnaires. We computed individual-item and subgroup mean scores for students, clinical instructors, and combined students and instructors. Subgroup mean scores were also computed. We computed Pearson product moment correlations to evaluate the level of agreement between the students' and instructors' individual-item means and between male and female students' individual-item means. Pearson product moment correlations were also computed for the individual-item mean responses with the proportion of respondents who identified items in the directed, open-ended listing of the 10 most and 10 least helpful characteristics.

RESULTS

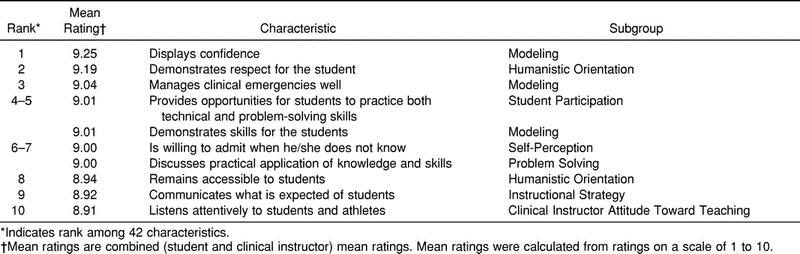

Of the 47 clinical instructor respondents, 25 (53.2%) had 10 or more years of experience, and 42 (89.4%) had a graduate degree. Of the 206 student respondents, 157 (76.2%) had 400 or more hours of clinical education experience, 146 (70.9%) were juniors or seniors, 127 (62%) were women, and 79 (38%) were men. The combined (student and clinical instructor) mean ratings for the 10 most helpful clinical instructor characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Most Helpful Clinical Instructor Characteristics

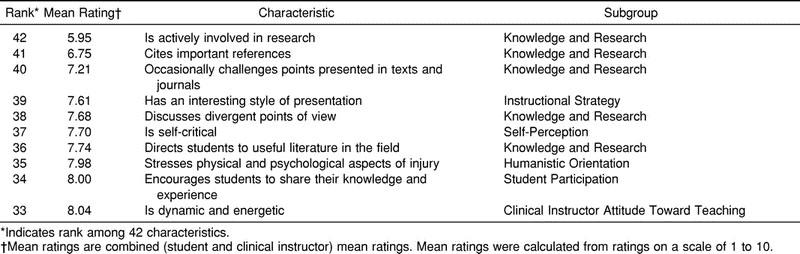

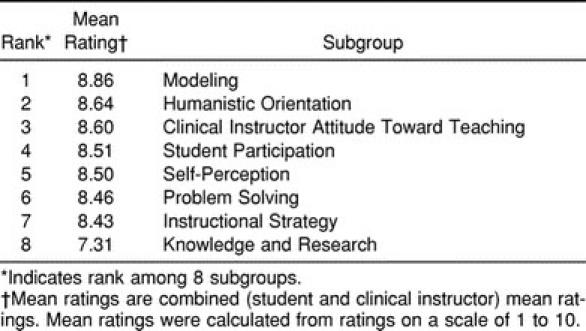

The combined mean ratings for the 10 least helpful characteristics are presented in Table 2. The mean score gives an indication of an individual item's helpfulness toward student learning, with 10 representing among the most helpful. The ranking gives the relative importance of each item in comparison with all other questionnaire items. Agreement was high between the students' and clinical instructors' mean ratings (r = .88) and between male and female students' mean ratings (r = .95). Agreement was also high between the combined mean Likert scores of students and clinical instructors and the items chosen in the directed, open-ended 10 most helpful characteristics (r = .83) and the directed, open-ended 10 least helpful characteristics (r = .95). As seen in Table 3, subgroup mean ratings ranged from 7.31 to 8.86. The Modeling subgroup contained the most helpful clinical instructor characteristics and had a subgroup mean of 8.86. “Displays confidence,” “manages clinical emergencies well,” and “demonstrates skills for the students” were perceived by both students and clinical instructors as the most important characteristics. Other Modeling characteristics, “works effectively with health care members,” “maintains rapport with patients/athletes,” “actively and regularly engages in clinical practice,” and “consults with others when needed,” also received high ratings (more than 8.0) by both the students and clinical instructors. Three of the top 5 individual-item means and 2 of the 10 directed, open-ended most helpful characteristics were from this subgroup. The Knowledge and Research subgroup had the lowest mean rating (7.31). Five of the lowest 7 individual-item means and 5 of the 10 directed, open-ended least helpful characteristics were from this subgroup. There was relatively little discrimination among the other 6 subgroups (means ranged from 8.43 to 8.64), with no particular pattern of individual-item means or directed, open-ended most and least helpful characteristics.

Table 2.

Least Helpful Clinical Instructor Characteristics

Table 3.

Subgroup Mean Ratings

DISCUSSION

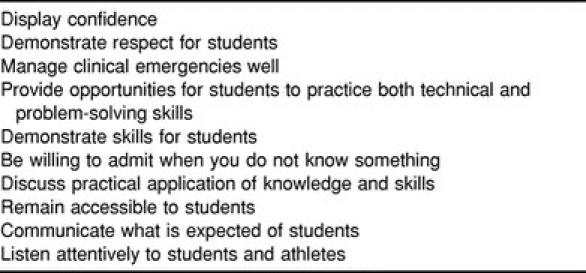

Athletic training clinical education is often judged by the quantity of clinical hours completed by a student. This perspective of clinical education places no value on the clinical instructor. The students' and clinical instructors' perceptions identified in this study of helpful clinical teaching characteristics can more meaningfully help direct the clinical instruction process. Table 4 presents teaching tips for athletic trainers serving as clinical instructors, which will also, we hope, serve as a catalyst for athletic trainers to seek professional development activities designed to improve clinical instruction.

Table 4.

Teaching Tips for Clinical Instructors

The small ratio of students to clinical instructors in athletic training clinical education allows clinical instructors to individualize instruction. Considering individualized instruction, Curtis et al7 recommended that sex differences be explored. We found no differences in the perceptions of male and female athletic training students regarding helpful clinical instructor characteristics, and therefore, the teaching tips presented in Table 4 can be used by clinical instructors regardless of the student's sex.

Modeling professional behavior is the most helpful category of clinical instructor characteristics. Clinical instructors need to demonstrate and consistently improve their knowledge and skills. Consistent with these modeling behaviors, good clinical instructors have been identified as being involved with the students, being clear and organized, emphasizing problem solving, mentoring, having sound communication skills, having a positive attitude, and providing good feedback.3,7,16–21 Quality clinical instructors have been described as being both master teachers and master practitioners.20 Modeling and its specific characteristics (eg, displaying confidence, managing clinical emergencies well, and demonstrating skills for students) are appropriately considered qualifications for these designations.

In other research,19 medical students indicated that involvement of their clinical instructors was an important consideration in learning. Modeling, identified in this research as the overall most important characteristic of clinical instructors, requires such involvement.

It is important to note that all of the clinical instructor characteristics framed in this study were considered helpful by students and clinical instructors and may improve student learning. The top 7 characteristics received mean scores of 9.00 or above on a 10-point Likert scale. The middle mean scores ranged between 8.00 and 9.00. Only the lower 8 items received mean scores below 8.00, with only the last 2 scores below 7.00. This pattern suggests that all of the characteristics identified in this study should be considered helpful or very helpful for facilitating student learning. No other subgroup of clinical instructor characteristics can be identified as the second most important for student learning. Student Participation, Clinical Instructor Attitude Toward Teaching, Problem Solving, Instructional Strategy, Humanistic Orientation, and Self-Perception all received very high ratings (8.43 to 8.64). There is little perceived difference overall among these other subgroups of helpful clinical instructor characteristics. From other research, however, there is evidence regarding the influence of negative clinical instructor characteristics on student learning. Clinical instructors should not treat students with disrespect, provide negative feedback, or be unavailable.7,16,20 These behaviors are perceived to hinder student learning.

The Knowledge and Research subgroup was consistently identified by both students and clinical instructors as the set of least helpful clinical instructor characteristics in student learning. It appears that both students and clinical instructors involved in undergraduate athletic training education likely focus more on learning subject matter and clinical skills than on conducting research to support clinical practices. Ultimately, for the athletic training profession to develop and mature, it must establish its own body of knowledge.22 The transmission of this knowledge to entry-level professionals through effective and proven instructional methods is also critically important. The actual practice or clinical application of athletic training should have shared importance with research and education. Perhaps a more balanced approach to entry-level athletic training clinical education would include avenues for infusing research into clinical practice. For example, emphasis on critical-thinking skills during clinical education may develop an appreciation of the need for athletic training research. Other avenues for infusing research into student athletic trainers' education may include undergraduate didactic education and graduate education.

CONCLUSIONS

Modeling professional behavior is perceived by students and clinical instructors to be the most helpful category of clinical instructor characteristics in student learning. Student Participation, Clinical Instructor Attitude Toward Teaching, Problem Solving, Instructional Strategy, Humanistic Orientation, and Self-Perception were all viewed as positive categories of characteristics that are helpful toward student learning; however, no clear discrimination (ie, differences in ratings) can be discerned between the items in these categories. Infusing research into clinical instruction is perceived to be the least helpful clinical instructor characteristic.

Although we focused this research on the clinical instructor characteristics perceived to be the most helpful toward student learning, we did not measure the impact of these characteristics on student skills and knowledge. Further research should compare clinical instructor characteristics with student success in mastering entry-level skills and competencies. Further research is also needed to determine the characteristics of students completing clinical education. What specific characteristics are necessary for a student to maximize the clinical education experience? Research should also focus on the clinical setting to determine the influence of environmental, administrative, and personnel factors on clinical instruction and student learning.

Although the more experienced sample of students in this study may have ensured that our responses were from a group familiar with clinical education, it may not have revealed differences in the perceptions between experienced and inexperienced students. Perhaps students with different levels of experiences, including entry-level undergraduate students and entry-level graduate students, have unique perceptions of helpful clinical instructor characteristics. Further research should also focus on the influence of student and clinical instructor learning styles on the perceptions of helpful clinical instructor characteristics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported through a grant from the Great Lakes Athletic Trainers' Association Research Assistance Fund (Thomas G. Weidner).

REFERENCES

- 1.Starkey C. Reforming athletic training education [editorial] J Athl Train. 1997;32:113–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson DC, Harris IB, Allen S, et al. Comparing students' feedback about clinical instruction with their performances. Acad Med. 1991;66:29–34. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199101000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Emery MJ. Effectiveness of the clinical instructor: students' perspective. Phys Ther. 1984;64:1079–1083. doi: 10.1093/ptj/64.7.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gjerde CL, Coble RJ. Resident and faculty perceptions of effective clinical teaching in family practice. J Fam Pract. 1982;14:323–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Infante MS, Forbes EJ, Houldin AD, Naylor MD. A clinical teaching project: examination of a clinical teaching model. J Prof Nurs. 1989;5:132–139. doi: 10.1016/s8755-7223(89)80111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Flom-Kegel P. Evaluating and improving clinical instruction. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1977;54:708–715. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197710000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtis N, Helion JG, Domsohn M. Student athletic trainer perceptions of clinical supervisor behaviors: a critical incident study. J Athl Train. 1998;33:249–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen MB, Larson GA, Luebe JJ. Student and supervisor perceptions of the quality of supervision in athletic training education. J Athl Train. 1997;32:328–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster DT, Leslie DK. Clinical teaching roles of athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 1992;27:298–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blue AV, Stratton TD, Plymale M, DeGnore LT, Schwartz RW, Sloan DA. The effectiveness of the structured clinical instruction module. Am J Surg. 1998;176:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slotnick HB. How doctors learn: the role of clinical problems across the medical school-to-practice continuum. Acad Med. 1996;71:28–34. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199601000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villafuerte A. Structured clinical preparation time for culturally diverse baccalaureate nursing students. Int J Nurs Stud. 1996;33:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(95)00047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sloan DA, Donnelly MB, Plymale MA, et al. Improving residents' clinical skills with the structured clinical instruction module for breast cancer: results of a multiinstitutional study. Breast Cancer Education Working Group. Surgery. 1997;122:324–333. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ladyshewsky RK, Barrie SC, Drake VM. A comparison of productivity and learning outcome in individual and cooperative physical therapy clinical education models. Phys Ther. 1998;78:1288–1298. doi: 10.1093/ptj/78.12.1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frisch NA, Coscarelli W. Systematic instructional strategies in clinical teaching: outcomes in student charting. Nurse Educ. 1986;11:29–32. doi: 10.1097/00006223-198611000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarski RW, Kulig K, Olson RE. Clinical teaching in physical therapy: student and teacher perceptions. Phys Ther. 1990;70:173–178. doi: 10.1093/ptj/70.3.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Irby DM. What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69:333–342. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199405000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Irby DM, Ramsey PG, Gillmore GM, Schaad D. Characteristics of effective clinical teachers of ambulatory care medicine. Acad Med. 1991;66:54–55. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199101000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irby DM, Gillmore GM, Ramsey PG. Factors affecting ratings of clinical teachers by medical students and residents. J Med Educ. 1987;62:1–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irby DM. Clinical teacher effectiveness in medicine. J Med Educ. 1978;53:808–815. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197810000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stritter FT, Hain JD, Grimes DA. Clinical teaching reexamined. J Med Educ. 1975;50:876–882. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osternig LR. Research in athletic training: the missing ingredient. Athl Train. 1988;23:223–225. [Google Scholar]