Abstract

Objective:

To familiarize athletic trainers with methodologic issues regarding the development and implementation of neuropsychological tests used in programs for monitoring sport-related cerebral concussion.

Data Sources:

Knowledge base and MEDLINE and PsychLit searches from 1980–2000 using the terms sports, athletes, concussion, and brain.

Data Synthesis:

Neuropsychological testing is a proven method for evaluating symptoms of concussion that results from a variety of different causes. These tests have been shown to be effective in evaluating symptoms of subtle cognitive dysfunction in a number of patient groups. Applying these tests in an athletic population has required some procedural modifications, including the use of brief test batteries, collection of preseason baseline data, and evaluation of subtle postconcussive changes in test scores over time. New methods are now being used for improved evaluation of the reliability and validity of neuropsychological tests in athletes. Proper scientific analysis of the psychometric properties of neuropsychological tests and the ultimate value of their use in the sport setting will require years of detailed study on large numbers of athletes with and without symptoms of concussion.

Conclusions/Recommendations:

Athletic trainers and related personnel need to be aware of the training and methodologic issues associated with neuropsychological testing. Knowledge of the scientific properties of these tests, their advantages, and current limitations will ultimately enhance the athletic trainer's ability to use information from neuropsychological testing in an effective manner.

Keywords: concussion, head injury, assessment, psychometrics

Symptoms of sport-related cerebral concussion are, by nature, subjective and vaguely defined. People who evaluate head injuries in the athlete need objective means to determine the pattern and severity of symptoms. The field of sports medicine has turned to neuropsychology, the scientific study of brain-behavior relationships, to provide methods that can be used on the sideline and in the athletic training room for assessment of postconcussive changes in orientation, concentration, and memory. In this article, I will review many of the methodologic issues involved in using neuropsychological tests and the advantages they offer for assessment of athletes with symptoms of sport-related cerebral concussion.

WHAT IS CLINICAL NEUROPSYCHOLOGY?

Clinical neuropsychology is a relatively new professional field that has evolved over the years from advancements in both clinical and experimental psychology to a distinct specialty. Individuals who practice clinical neuropsychology are doctoral-level professionals who specialize in the evaluation of diseases that affect the brain. Clinical neuropsychologists complete graduate training in psychology plus additional training at the internship and postdoctoral levels in the assessment and treatment of brain disorders. The practice of neuropsychology requires state licensure as a psychologist. Many practitioners also receive board certification in the field. Most neuropsychologists work in medical and mental health facilities, whereas others work in private practices or rehabilitation settings.

Assessment of concussion is by no means new to the field of neuropsychology. Many years of experience have gone into developing tests for evaluating impairments in attention, memory, and higher-order executive functions that may be exhibited by those with concussion secondary to various causes, including motor vehicle crashes, work injuries, or violent crimes.

Neuropsychologists are very much aware that no single test is effective in diagnosing the presence or absence of concussion. The tests that are used are not effective when used in isolation, and they are not designed for that purpose. Neuropsychological tests are administered most appropriately as groups, otherwise termed test batteries.1 The purpose of using a test battery is to look for consistencies in symptoms as exhibited in variations among a number of different test scores. In a typical clinical setting, assessment of a patient with a concussion often requires a long test battery that may take from 4 to 8 hours to administer. Neuropsychologists are trained to evaluate the patient's motivational and emotional states, in addition to measuring the pattern and severity of cognitive impairment. They also consider to what degree an individual's age, educational background, or a multitude of other factors may influence test performance. Interpretation of these tests takes years of clinical training supplemented by extensive clinical experience. These are among the many reasons why neuropsychological tests need to be administered and interpreted under the immediate supervision of a doctoral-level psychologist who has obtained the requisite training.

NEUROPSYCHOLOGY IN THE SPORT SETTING

Moving from the clinical laboratory to the sport setting has provided new challenges and opportunities for the field of clinical neuropsychology.2–4 Sport-related concussion occurs on the practice or playing field, where methods for an immediate assessment of symptoms are needed. Many teams do not have the financial resources to send their athletes for extensive neuropsychological evaluations. Athletes rarely have the time to undergo a 4- to 8-hour examination in the midst of the season. The ages of athletes participating in organized sports range from childhood to mid adulthood, and participants come from a variety of cultural and educational backgrounds. Previous studies5 have demonstrated that learning disabilities are prevalent and effective in influencing neuropsychological test performance. In contrast to a typical patient with concussion whose self-reports of symptoms brings him or her to medical attention, athletes are often known to minimize the severity of their symptoms to remain on the active roster. The emotional and motivational factors that influence neuropsychological test performance in athletes are markedly different from those seen in other individuals with concussion.

Neuropsychology has made many recent advances to meet the demands of the sport setting. A neuropsychological method for evaluating symptoms immediately following concussion has been developed by McCrea et al.6,7 The Standardized Assessment of Concussion (SAC) is a brief (5-minute), standardized measure of orientation, concentration, and memory that can be given at the sideline by athletic trainers and other team officials who have received training in its administration and interpretation. The SAC comes in alternate forms, devised to avoid the presence of “learning effects,” which are liable to occur when tests are administered on more than one occasion. In its typical use, the SAC is administered to all players at the beginning of the athletic season to obtain a baseline of their performance. Athletes with suspected concussion are administered an alternate form of the SAC to determine if there are any changes in scores that would represent the effects of concussion. This information is used with other clinical criteria to make decisions about return to play and the need for a more extensive neurodiagnostic workup, including a neurologic consultation and more detailed neuropsychological testing.

Models of assessment using more extensive batteries of neuropsychological tests have been developed for use with athletes during the past 10 to 15 years.2,3 These batteries are being implemented by an increasing number of teams in the high school, college, and professional ranks to assess more persistent symptoms that may result from concussion. The approach consists of a brief (20- to 30-minute) test battery that is used to obtain baseline information on the athlete before the athletic season. Athletes who receive a concussion during the season are sent to a neuropsychological consultant for additional testing within 24 to 48 hours after the injury to determine the presence or absence of changes from the initial test performance. Objective information regarding the player's cognitive functioning is then provided to the team's medical staff to help them make determinations about return to play. Athletes who exhibit clear features of cognitive disturbance attributable to concussion are then followed up with additional testing until their test scores return to baseline levels.

The demands of the sport setting make it necessary for neuropsychologists to adopt test batteries that are shorter and more portable than those used in a typical clinical or hospital setting. The availability of baseline results is crucial to these models of testing. Obtaining baseline information on a given player enables the neuropsychologist to shorten the neuropsychological test battery by avoiding the use of long and arduous tests for evaluating overall intelligence and estimating premorbid level of functioning. The use of serial testing enables the neuropsychologist to control for many pre-existing factors, including intelligence, cultural factors, and a medical history, including effects of previous concussions, that might be influencing the athlete's test scores. With baseline test results available, the neuropsychologist can make informed decisions about the presence or absence of changes in cognitive functioning over time by using the athlete's previous functioning as a starting point.

Although the use of brief test methods administered during several periods provides many advantages, a number of methodologic challenges exist for the neuropsychologist working in the sport setting. Many of these are reviewed herein.

PSYCHOMETRIC PROPERTIES OF NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL TESTS

A clinical examination is a systematic evaluation designed to elicit pathologic signs or symptoms. In the past, sideline evaluation of an athlete with suspected concussion might have included a number of haphazard questions about the current location, date, or score of the game. Many of the same questions would then be repeated during follow-up examinations. Neuropsychological tests offer the advantage of being standardized in their administration and use. This means that the procedures, materials, and scoring of the tests are fixed so that the same precise methods can be followed by others at different times and places. This type of testing offers a means of observing symptoms in a controlled manner, with the use of a numeric scale that can be compared with previous test scores or with scores obtained from other individuals who have been administered the same procedure. Using these methods, officials from one team can compare their athletes' test results with those obtained from another team or evaluate how an athlete's performance compares with published norms taken from a large sample of athletes.

The development and standardization of a neuropsychological test take many steps. These steps include deciding on the psychological construct or symptom to be evaluated, establishing the format of questions or procedures to be administered, and performing a series of scientific experiments to determine the quality of the information the test provides.

Individuals experiencing a concussion often report feeling “slowed down” or “foggy.”8 They also report difficulties with processing and retaining information. Clinicians have known for years that disturbances in concentration and memory are among the most prominent and most persisting complaints. Neuropsychologists who investigate the underlying features of these cognitive disturbances have developed a number of paper-and-pencil tests of sustained attention, learning, and recall to be used as objective measures of these often vaguely defined symptoms. Years of work have gone into the development of these measures. Scientific studies have been performed to determine whether the tests are able to properly assess the process in question and whether they are able to accurately identify impairments in patients with verified brain dysfunction.9

Neuropsychologists turn to the field of psychometrics, the study of psychological tests and measurements, to evaluate the scientific quality of their measures. In this context, the terms reliability and validity are often used. Reliability refers to the consistency or stability of test scores when they are obtained for an individual after repeated observations or under different testing conditions.10 When discussing reliability, one needs to consider both the “true score,” which would be the value obtained if the test were a perfect measure of the ability in question, and the “test error,” which represents the effects that other factors may impose on the measurement process. Neuropsychologists are well aware that there is no error-free test. Thus, one can assume that a test score reflects some reality of the measurement in question. However, one must also consider other factors that clearly can contribute to the overall test score. These may include random influences, such as motivational state or factors specific to the testing conditions, such as the presence of extraneous noise in the room. Other factors may be attributed to inherent inaccuracies in the test itself. Much of a test's value lies in its ability to maximize its assessment of a given ability while minimizing the effects of these extraneous error factors.

Validity is a concept that refers to how well an instrument measures what it is supposed to be measuring.10 This is an extremely important issue in the field of neuropsychology. Neuropsychologists consider many aspects of validity when a decision is made whether or not to use a particular test. One of these concerns whether the content of the test provides an accurate representation of the symptom in question. Another factor to consider is how performance on the test in question compares with other tests that have been established for evaluating the same symptom. Finally, one must know the demonstrated accuracy of the test in making a clinical decision. When using tests to measure symptoms of brain dysfunction, the neuropsychologist needs to know how successfully the tests have been used to distinguish between those with and without independently verified features of brain impairment.

Performing a validation study on a neuropsychological test requires sampling an adequate number of subjects to demonstrate the efficacy of the measure. Samples sizes of 35 or more subjects with independently diagnosed conditions are needed to perform the statistical analyses necessary to study the condition in question. Some suggest that sample sizes exceeding 400 subjects may be required.11 This presents a challenge when evaluating a condition such as sport-related cerebral concussion, for which the expected rate of occurrence in a sample of high school football players is less than 4%.12 To properly determine the validity of a test in evaluating symptoms in this population, one would minimally need to study 875 athletes at baseline, follow up the athletes closely throughout the season, and identify all the subjects who develop symptoms of concussion. To establish more precise validity statistics, samples sizes of 10 000 need to be obtained. The time and effort required to perform an acceptable validation study in athletes is certainly not negligible.

Reliability and validity provide the foundation of all forms of scientific measurement, including neuropsychological testing. Accurate interpretation of the neuropsychological test findings is based on the premise that the test is reasonably free of measurement error or random influence and that the test can be used to support a specific clinical inference, such as the presence or absence of cognitive dysfunction secondary to brain injury. In basic terms, the psychometric properties of a given test instrument, combined with the experience of using it, directly affect the neuropsychologist's ability to trust that a given score may represent a “true” performance accurately measuring the symptom in question. An example of the steps required for proper development and implementation of a neuropsychological test is provided herein.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE SYMBOL DIGIT MODALITIES TEST

Developing a neuropsychological test requires an extensive amount of work. This will be illustrated with a discussion of the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT), a measure that is frequently used for assessment of sport-related concussion. Most of the teams in the National Hockey League and the National Football League are now using the written version of this test. The test is also now included in test batteries used by the increasing number of concussion monitoring programs developed for high school and collegiate athletes.

The SDMT was developed as a measure of sustained attention and concentration by researchers at the University of Michigan in the late 1960s for use in screening for cerebral dysfunction in adults and children.13 The test requires rapid transcription of meaningless designs into numeric responses. The final score reflects the number of correct transcriptions performed in 90 seconds. Standardized instructions for administration and methods for scoring and interpreting the test are provided in the test manual.13

Normative data for the SDMT were obtained from studies performed on a total of 1307 adult volunteers and 3680 children.13 Evidence for the reliability of the test was initially obtained in a study of 80 adults administered the test in 2 test sessions throughout approximately 30 days. Comparisons of test scores obtained at times 1 and 2 resulted in a test-retest correlation of 0.80. Individuals tested at baseline obtained a score of 56.79 ± 9.84. Scores increased an average of 3.67 points to 60.46 ± 11.16 at retesting. The increase in scores at time 2 reflects a “practice effect,” a feature that is commonly seen in test-retest situations.

The data, taken together, indicate that approximately 64% of the variance can be accounted for by a feature that is intrinsic to the SDMT. The other 36% of the variance is thus attributable to random error, including these observed practice effects. Although this figure may seem high, it is similar to the degree of error observed in similar tests of these abilities. This finding illustrates the fact that neuropsychological measures do not provide error-free indexes of complex abilities such as cognitive functioning. However, these methods are currently the best measures that science has to offer.

Research has shown that scores obtained from SDMT correlate with other measures of attention and concentration. Investigators comparing scores from the SDMT and the Digit Symbol subtest from various versions of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale have found correlation coefficients ranging from 0.73 to 0.79.1 In one study, the pooled correlation coefficient with a group of other commonly used test measures, including the Stroop Color Word Test, Paced Auditory Serial Addition Test, and measures of simple and choice reaction time, was 0.58.14 Early validity studies were performed on individuals with and without brain dysfunction. Scores obtained from 36 individuals with brain trauma were lower than those observed in the controls.13 The SDMT has been shown effective in discriminating between subjects with head injuries and controls.14 Its sensitivity to detecting symptoms of concussion in a sample drawn from an initial total of 2350 athletes has also been demonstrated.2

DEVELOPMENTS IN EVALUATION OF TEST RELIABILITY

Assessment of clinical change is essential to the use of neuropsychological testing in the management of concussion in the sport setting. The major premise is that decreases from baseline test scores at retesting signal the presence of cognitive impairment secondary to concussion. Increasing scores in subsequent testing reflect improvement in functioning, with an eventual return to the baseline level. Accurate detection of changes in test scores is a critical component to detection of the often subtle changes in behavior after concussion.

As mentioned herein, understanding the reliability of a given test is important when examining changes in test scores over time. In many applications, psychological tests can provide highly reliable scores, particularly when stable traits, such as verbal skills or personality characteristics, are assessed.10 Unfortunately, this is not the case when assessing symptoms of concentration disturbance in conditions, including concussion. In studies of healthy individuals, it is well known that scores on tests of attention, processing speed, and memory are among the most unreliable indexes, since they happen to be most prone to the influence of “normal” confounding factors, such as anxiety level and fatigue.9 The situation becomes even more complicated when evaluating individuals who have sustained a concussion, when the goal is to assess changes attributable to mild brain dysfunction. In these patients, one must consider not only the effects of normal variations in test scores but also those attributed to the added influence of other factors, including pain and possible side effects of medications.8 Those evaluating changes in neuropsychological functioning that result from concussion are thus faced with the difficult challenge of measuring subtle changes in symptoms having inherently low levels of reliability in the presence of a multitude of other factors that may cause confounding changes in test scores.

Development of newer tests with increasing levels of reliability might help to address some of the issues encountered when evaluating changes in attention and concentration test scores over time. Given the length of time needed to develop and study the use of new tests, this is not likely to provide any immediate solution to the problem. In the meantime, neuropsychologists are evaluating new ways to interpret changes in test scores in those measures currently in use.

Some investigators have studied the use of Reliable Change Indices (RCIs) as a method of evaluating “true” changes in test scores over time.15,16 An RCI is a statistical method for developing cutoff scores that are useful for evaluating meaningful changes in test scores independent of psychometric issues, such as practice effects and other sources of variance.

Computation of an RCI can be performed on any neuropsychological test measure that has been studied through a test-retest paradigm with the population of interest. The standard error of the difference is derived and standardized according to the normal distribution. In its typical use, the RCI results in a difference score, representing changes that occur in less than 5% of the study sample. Change scores that exceed this level thus represent the effects of “true” changes attributable to the effects of concussion or recovery. Recent applications of the RCI paradigm in the sport setting have been conducted on studies of Australian National Rugby League professionals17; these authors have determined that reliable changes can be detected with a 6-point difference on the SDMT. Thus, players retested after injury with decreases of 6 points or more on the SDMT are likely to be showing impairments in processing speed attributable to the effects of concussion. Similar studies are currently under way to derive RCIs for other tests in current use with athlete populations.

DEVELOPMENTS IN EVALUATION OF TEST VALIDITY

Those contemplating using neuropsychological testing as part of their concussion management program often ask, “How accurate are these tests in evaluating the effects of concussion?” This is a question about the validity of the tests. As mentioned herein, most of the neuropsychological tests currently used in sport settings have been validated in previous studies of concussion. Further validation through more specific studies of athletes with concussion is currently under way.

Assessing the validity of neuropsychological tests is typically limited to the analysis of group means. For example, if patients with traumatic brain injury are found to have significantly lower scores on a given memory test than healthy controls, then that memory test is usually considered to provide a valid measure of memory impairment associated with brain injury. What is not assessed by this type of analysis, however, is what proportion of patients can be correctly classified into brain-injured and non–brain-injured groups by a given score on the test. Analyses of classification rates and the diagnostic accuracy of clinical test data are often overlooked in neuropsychological studies of test validity.

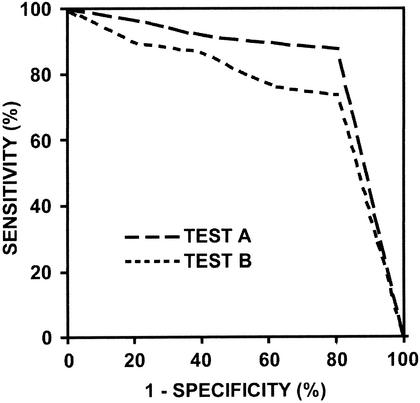

Interest is now turning to studying the ability to predict the outcome of an individual case. To address this issue, an increasing number of investigators are assessing the accuracy of neuropsychological tests through the use of signal detection statistics and computation of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.18,19 Signal detection statistics provide indexes of the ability to make a clinical decision when faced with a given criterion or test score. The sensitivity of a measure refers to the proportion of individuals with the condition in question whose scores exceed that criterion. Specificity of a measure refers to the number of individuals without the condition classified accurately as not achieving that criterion. The ROC curves provide graphic representations of the tradeoff between true-positive and false-positive rates of classification. Calculation of the area under the ROC curve provides an empirical method for determining the diagnostic accuracy of a given test or helping to determine which of 2 tests is more accurate for diagnosing a certain condition. An example of ROC curves for 2 hypothetical tests is provided in the Figure.

Receiver operating characteristic curve for hypothetical tests A and B developed for assessment of concentration disturbance secondary to sport-related concussion. Sensitivity and specificity values for classification of athletes with and without concussion are represented graphically for both tests. The larger area under the curve indicates that test A provides more accurate classification of these 2 athlete groups. This finding can be demonstrated empirically through statistical comparison of area-under-the-curve values for both tests. Such information would be used to establish that test A is a more valid and sensitive measure for assessing the effects of concussion than test B.

Only a few researchers have addressed the diagnostic accuracy of using neuropsychological tests for assessment of concussion in a sport setting. In a recent study using the SAC, a decline of 1 point or more from baseline was observed in 94% of a sample of 50 high school and collegiate football players assessed within 15 minutes of experiencing a concussion.20 This level of decline was observed in only 24% of a sample of uninjured athletes undergoing routine retesting as part of a larger study. These results provide further validation of the use of the SAC as a measure of the immediate effects of concussion in athletes. The study also provides the clinician with information that athletes who exhibit a decline from their baseline score on this measure after injury will have more than a 90% chance of exhibiting the effects of concussion as opposed to a less than 25% chance of a false-positive error. Information of this nature is of obvious benefit to the clinician, who will use this information, with his or her experience and other relevant information, to make decisions about return to play. Similar statistics regarding sensitivity and specificity will be available for other neuropsychological tests once a number of ongoing studies with athletes have been completed.

DISCUSSION

Neuropsychological testing provides a scientific method for evaluating symptoms of cognitive dysfunction that result from sport-related cerebral concussion. The ultimate goal in using these tests is to provide the athletic trainer and team physician with objective information to help them arrive at a decision about return to play or the need for obtaining additional workup. Neuropsychological test results should not be used in isolation but rather in the context of a full postinjury evaluation, including all appropriate and available methods.

Many athletic trainers inquire about the requirements for implementing neuropsychological testing programs for their athletes. One must first consider the fact that the practice of neuropsychological assessment requires years of specific preparation, consisting of graduate school course work and clinical training. Most states require a license in psychology to purchase and use these instruments in a clinical setting. Thus, by law, the clinical application of neuropsychological test batteries in a sport setting should be conducted under the direct supervision of a licensed psychologist who has received training in the use of these instruments. Athletic training staff and trainees should be encouraged to receive instruction in the use of more portable screening instruments, such as the SAC, for immediate assessment of athletes on the sideline. One must remember that these screening measures have been developed for evaluation of the immediate effects of sport-related concussion and provide the team medical staff with information regarding the need for more detailed medical evaluation, including neuropsychological assessment.

The development and validation of neuropsychological tests require years of work and studies of large numbers of subjects. Test batteries currently used for assessing athletes represent an adaptation of methods developed for use in a hospital or clinical setting. The potential to obtain baseline test results on an “at-risk” athletic population represents a relative advantage over the typical clinical situation, in which information regarding the subject's uninjured state is rarely available. In athletes, time constraints require the use of brief neuropsychological test batteries that can be completed in less than ½ hour. Emphasis on the analysis of changes from baseline to postinjury scores requires detailed knowledge about the performance of the tests when given on multiple occasions. The relative brevity of the battery places more attention on the ability of each test to detect subtle changes that result from brain injury. Much more work needs to be done to further our understanding about the reliability and validity of neuropsychological tests when used with an athletic population.

Scientific advances are now being made to provide more precise information about the use of neuropsychological testing with athletes. Information including RCIs to determine changes in scores and signal detection statistics cannot be used blindly by sports medicine clinicians in their care of athletes with known or suspected concussion. There will never be a neuropsychology “cookbook” that spells out all the decision rules regarding the use of these test scores. Although the tests may yield a plethora of numbers, the ultimate use of this statistical information remains with the decision-making team, with much room for interpretation. For example, if neuropsychological test scores yield a “conservative” estimate of an 80% chance that a particular athlete has experienced a concussion, parents and educators might want the athlete to remain out of competition. Coaches or other team officials, however, might view the same numbers as indicating a 20% chance of no symptoms and recommend an immediate return to play. It should be made clear that the cutoff points used in any statistical decision are ultimately arbitrary and need to be set by the clinician, depending on experience and the question at hand.

Neuropsychological testing has been used in the sport setting increasingly during the past 5 years. Although the tests have shown promise in the management of sport-related cerebral concussion, their limitations should be realized. These measures provide the scientific “state of the art” for assessment of cognitive dysfunction secondary to a wide range of medical causes, although they are by no means perfect. The field of clinical neuropsychology is known for being more critical of its methods than other health-related disciplines. This ultimately results in continued studies of ways to improve methods. Continued use of neuropsychological tests is recommended despite their inherent flaws, although athletic trainers and team medical personnel have a right to suspend judgment about their ultimate value in a sport setting until more information about their use in athletes has been obtained.

Scientific data regarding the reliability and validity of the most commonly used paper-and-pencil tests are now emerging and are appearing increasingly in the professional literature. These data are the results of many years of hard work testing many thousands of individual athletes. New computerized methods for assessing neuropsychological functioning in athletes are now in development. Athletic trainers should remain skeptical about these more automated methods until their psychometric properties, including reliability and validity, have been demonstrated in an empirical manner on adequate numbers of athletes, both with and without symptoms of concussion. Keeping in mind the methodologic issues involved in the development and use of these methods will ultimately make the athletic trainer an informed consumer of neuropsychological testing services, both in the present and in the future.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lezak M. Neuropsychological Assessment. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth JT, Alves WM, Ryan TV, et al. Mild head injury in sports: neuropsychological sequelae and recovery of function. In: Levin HS, Eisenberg HM, Benton AL, editors. Mild Head Injury. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1989. pp. 257–275. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lovell MR, Collins MW. Neuropsychological assessment of the college football player. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13:9–26. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199804000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maroon JC, Lovell MR, Norwig J, Podell K, Powell JW, Hartl R. Cerebral concussion in athletes: evaluation and neuropsychological testing. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:659–669. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200009000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Collins MW, Grindel SH, Lovell MR, et al. Relationship between concussion and neuropsychological performance in college football. JAMA. 1999;282:964–970. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.10.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCrea M, Kelly JP, Kluge J, Ackley B, Randolph C. Standardized assessment of concussion in football players. Neurology. 1997;48:586–588. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.3.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCrea M, Kelly JP, Randolph C, et al. Standardized assessment of concussion (SAC): on-site mental status evaluation of the athlete. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13:27–35. doi: 10.1097/00001199-199804000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexander MP. Mild traumatic brain injury: pathophysiology, natural history, and clinical management. Neurology. 1995;45:1253–1260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.7.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franzen MD. Reliability and Validity in Neuropsychological Assessment. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anastasi A. Psychological Testing. New York, NY: MacMillan Publishing Co Inc; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charter RA. Sample size requirements for precise estimates of reliability, generalizability, and validity coefficients. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1999;21:559–566. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.4.559.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell JW, Barber-Foss KD. Traumatic brain injury in high school athletes. JAMA. 1999;282:958–963. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.10.958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith A. Symbol Digit Modalities Test Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ponsford J, Kinsella G. Attentional deficits following closed-head injury. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1992;14:822–838. doi: 10.1080/01688639208402865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chelune GJ, Naugle RI, Luders H, Sedlak J, Awad IA. Individual change after epilepsy surgery: practice effects and base-rate information. Neuropsychology. 1993;7:41–52. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hinton-Bayre AD, Geffen GM, Geffen LB, McFarland KA, Friis P. Concussion in contact sports: reliable change indices of impairment and recovery. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1999;1:70–86. doi: 10.1076/jcen.21.1.70.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr WB. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis of Wechsler Memory Scale: revised scores in epilepsy surgery candidates. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:171–176. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFall RM, Treat TA. Quantifying the information value of clinical assessments with signal detection theory. Ann Rev Psychol. 1999;50:215–241. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barr W, McCrea M. Sensitivity and specificity of standardized neurocognitive testing immediately following sports concussion. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. In press doi: 10.1017/s1355617701766052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]