Abstract

Objective To quantify the prevalence and characteristics of hardcore smokers in England.

Design Cross sectional survey.

Setting Interview in respondents' household.

Participants 7766 adult cigarette smokers.

Main outcome measures Hardcore smoking defined by four criteria (less than a day without cigarettes in the past five years; no attempt to quit in the past year; no desire to quit; no intention to quit), all of which had to be satisfied.

Results Some 16% of all smokers were categorised as hardcore. Hardcore smoking was associated with nicotine dependence, socioeconomic deprivation, and age, rising from 5% in young adults aged 16-24 to 30% in those aged ≥ 65 years. Hardcore smokers displayed distinctive attitudes towards and beliefs about smoking. In particular they were likely to deny that smoking affected their health or would do so in the future. Prevalence of hardcore smoking was almost four times higher than in California.

Conclusion Hardcore smoking presents a serious challenge to public health efforts to reduce the prevalence of smoking, but the proportion of hardcore smokers does not necessarily increase as overall prevalence in a population declines. More hardcore smokers could be persuaded to quit, but this will require interventions that are targeted to the particular needs and perceptions of both socially disadvantaged and older smokers.

Introduction

The idea that there might exist a group of cigarette smokers who are especially resistant to giving up has attracted considerable interest. 1,2 No generally accepted definition of a hardcore smoker exists, but by consensus they are those who are very unlikely to give up, either because they are determined not to or because they lack any confidence in their ability to do so successfully. One version of the hardcore hypothesis postulates that as prevalence of smoking declines over time in a population, those who continue to smoke will be increasingly intransigent, possibly with both high dependence and low motivation to quit. 3 It is also plau-sible that in any given cohort of smokers, those who want to quit and are able to change their behaviour successfully will succeed as they get older, with the result that older smokers, on average, may be more likely to be hard core than younger smokers.

There have been few attempts to quantify the extent of hardcore smoking. Recent estimates from California have indicated that about 5% of smokers aged 26 and above could be considered hard core. 4 The Californian study adopted an operational definition based on three principal characteristics: no attempts to quit in the past 12 months; an expectation of never quitting in the future; and cigarette consumption of at least 15 cigarettes per day. Typical hardcore smokers were older, white, male, of low income, poorly educated, and living alone.

We examined the prevalence and demographic correlates of hardcore smoking in Britain. Our preferred definition was different from that used in the Californian study. We did not include cigarette consumption as one of our criteria but placed additional weight on the absence of quitting in the past and on the lack of desire to give up smoking as well as lack of intention. The main justification for including cigarette consumption as a criterion is that it is an indicator of dependence on tobacco. We prefer a concept of hardcore smoking that is based entirely on measures reflecting motivation. The extent to which dependence is associated with hardcore smoking can then be assessed. However, for purposes of comparison, we also estimated the prevalence of hardcore smoking using the Californian definition.

Methods

The data considered here were gathered in four surveys of adults in England that were commissioned by the Health Education Authority as part of its national smoking education campaign. 5 The first survey was carried out in November/December 1994, the second in March/April 1995, the third in April/May 1996, and the fourth in May/June 1997. These surveys monitored smoking prevalence and consumption, provided information about smokers' attitudes and beliefs, and examined smokers' recent attempts at quitting and their desires, intentions, and confidence of succeeding in future attempts. Each survey used the same methods. Households were selected by a random probability sampling technique, using the postcode as the sampling frame, with a method that ensured comparability between waves.

When interviewers made successful contact, they collected basic demographic details and smoking habits for each adult in the household from an index respondent. In households where it was established that a current cigarette smoker (or someone who had given up within the past six months) lived, interviewers carried out a more detailed interview with that person. When two or more people were eligible, a random selection process was used. Response rates for the initial household interview averaged just over 80% across the four surveys, and the more detailed interview with selected smokers or recent ex-smokers was completed with 67%, 63%, 61% and 63%, in surveys one to four, respectively. The data reported here were gathered at the detailed interview. The survey methods are described more fully elsewhere. 5

We defined hardcore smoking in terms of several indicators, including both previous behaviour and future desires and intentions. To be classified as a hardcore smoker, respondents had to satisfy all of the following criteria: less than a day without cigarettes in the past five years (based on response to “Not counting times when you were ill or in hospital, what is the longest time you have ever gone without smoking over the past five years?”); no attempt to give up smoking in the past 12 months (no to “Are you currently trying to give up smoking altogether” and to “In the last 12 months have you tried to give up smoking altogether?”); no to “Do you want to give up smoking altogether?”; no intention to give up smoking (selection of response option “I don't intend to give up smoking” from multiple choice options assessing future intention to give up).

Several indicators of socioeconomic status were available. Occupational class of the main income earner in the household was categorised as manual or non-manual. Housing tenure was dichotomised into rented and owner occupied. Age of completing full time education was scored as 16 or less or older than 16 years. These were combined into a summary index of socioeconomic deprivation, as in previous studies, 6,7 assigning a score of 1 to each of manual class, rented housing, and completing education by age 16 years. This gave a total score ranging from 0 in the most affluent to 3 in the most deprived respondents. Available indicators of dependence on smoking included time to first cigarette of the day, average daily cigarette consumption, and age at starting to smoke regularly.

We examined the univariate significance of associations between hardcore smoking and variables of interest using χ2 tests and conducted multiple logistic regression analyses to assess the independent predictive contribution of age, sex, socioeconomic deprivation, and tobacco dependence. We combined the data from all four surveys. An indicator variable for wave of survey was entered into all multivariate statistical analyses.

Results

Information was available for 7766 current cigarette smokers. Of these, 1216 (16%) were classified as hardcore smokers. Table 1 gives characteristics of all the smokers. The most striking difference was that hardcore smokers were about 10 years older on average and tended to be more dependent on tobacco. Significantly more hardcore smokers had manual occupations, lived in rented accommodation, and had completed their full time education by the age of 16 years. There was no difference by sex.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hardcore and other smokers. Figures are numbers (percentage) of people unless stated otherwise

| Hardcore (n=1216) | Other smokers (n=6550) | |

|---|---|---|

| Want to quit | 0 | 4205 (64.2) |

| Intend to quit | 0 | 4461 (68.1) |

| Attempted to quit in past 12 months | 0 | 2646 (40.4) |

| Median time without smoking in past 5 years * | <1 day | 1-4 weeks |

| Men | 545 (44.8) | 2974 (45.4) |

| Mean age (years) | 51.9 | 41.4 |

| Completed education by age 16 | 1029 (84.6) | 4736 (72.3) |

| Living in rented housing | 541 (44.5) | 2699 (41.2) |

| Manual occupation | 777 (63.9) | 3838 (58.6) |

| First cigarette within 30 minutes of waking | 824 (67.8) | 3584 (52.8) |

| Mean daily cigarette consumption | 15.4 | 13.6 |

| Started smoking before age 16 | 565 (46.5) | 2646 (40.4) |

Original responses were choices from several ranges.

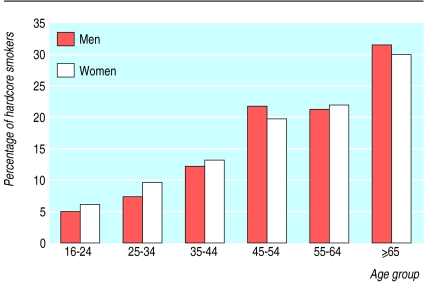

We examined the independent association of these predictor variables with hardcore smoking in a multiple logistic regression analysis ( table 2). The strongest predictor was age. The odds of being a hardcore smoker rose in a linear fashion with increasing age to nearly 8 in those aged ≥ 65 years compared with smokers aged 16-24 years ( figure). About 5% of smokers in the youngest age group scored as hard core, rising to 30% in those aged ≥ 65. There was also a significant trend of higher odds with increasing socioeconomic deprivation. By comparison with the most affluent, odds of hardcore smoking were 1.4 in the most deprived group. All three of the dependence indicators had independent predictive value, but the association was strongest with time to first cigarette. Odds of hardcore smoking were 2.3 among those who lit their first cigarette of the day within 5 minutes of waking compared with smokers who waited for two hours or more before having their first cigarette.

Table 2.

Multiple logistic regression * predicting hardcore smoking

| No | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex: | ||

| Men | 3484 | 1.00 |

| Women | 4202 | 1.14 (1.00 to 1.30) |

| Age (years): | ||

| 16-24 | 1134 | 1.00 |

| 25-34 | 1730 | 1.46 † (1.08 to 1.99) |

| 35-44 | 1477 | 2.21 † (1.63 to 2.98) |

| 45-54 | 1346 | 3.97 † (2.96 to 5.32) |

| 55-64 | 916 | 4.36 † (3.21 to 5.93) |

| ≥65 | 1083 | 7.95 † (5.94 to 10.65) |

| Deprivation score: | ||

| 0 | 1005 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 2163 | 1.10 (0.86 to 1.41) |

| 2 | 2853 | 1.19 (0.94 to 1.51) |

| 3 | 1665 | 1.41 † (1.10 to 1.81) |

| Time to first cigarette: | ||

| <5 min | 1324 | 2.27 † (1.73 to 2.97) |

| 5-15 min | 1259 | 1.80 † (1.38 to 2.35) |

| 15-30 min | 1659 | 1.85 † (1.43 to 2.39) |

| 30 min-1 hour | 1365 | 1.55 † (1.18 to 2.02) |

| 1-2 hours | 812 | 1.19 (0.87 to 1.62) |

| ≥2 hours | 1267 | 1.00 |

| Age when person started to smoke: | ||

| ≤15 | 3189 | 1.46 † (1.24 to 1.72) |

| 16-17 | 2087 | 1.23 † (1.03 to 1.47) |

| ≥18 | 2410 | 1.00 |

| Cigarette consumption/day: | ||

| 0-9 | 2287 | 1.00 |

| 10-19 | 2992 | 0.93 (0.78 to 1.11) |

| 20-29 | 1937 | 1.24 † (1.03 to 1.50) |

| ≥30 | 470 | 1.49 † (1.14 to 1.94) |

Model included term for survey number, but this variable was not a significant predictor and coefficients are not shown.

P<0.05.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of hardcore smoking by age and sex: England 1994-7

Differences in attitudes and beliefs

We compared attitudes towards and beliefs about smoking in hardcore and other smokers ( table 3). There were several striking differences. Hardcore smokers were much more likely to reject the notion that smoking was currently harming their health or would do so in the future. As many as a third of hardcore smokers thought that their current health was completely unaffected by smoking compared with 13% of other smokers. They were also much less willing to acknowledge that stopping smoking would lead to an improvement in health and much less likely to see an improvement in health as a personal advantage if they were to give up. Hardcore smokers were more likely to see smoking as their main pleasure in life (31% v 14%) and were likely to strongly agree that they enjoyed smoking too much to give it up (58% v 21%). They were very ready to agree that there were things that were far worse for them than smoking (41% v 25%).

Table 3.

Comparison between hardcore and other smokers on attitudes towards and beliefs about smoking. Figures are percentage who responded as shown

| Response | Hardcore smokers | Other smokers | x2 (df=1) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much, if at all, do you think the amount you smoke affects your health now? | Not at all | 33.2 | 13.2 | 315.3 | <0.001 |

| How much, if at all, do you think the amount you smoke will affect your health in the future? | Not at all | 18.6 | 5.1 | 444.8 | <0.001 |

| Improvement of health would be a main advantage of giving up for me personally | Agree | 30.5 | 58.6 | 326.2 | <0.001 |

| I enjoy smoking too much to give it up | Strongly agree | 57.5 | 20.7 | 615.4 | <0.001 |

| I don't think I could give up smoking because I would suffer too much from withdrawal symptoms | Strongly agree | 28.2 | 16.2 | 94.1 | <0.001 |

| Smoking is my main source of pleasure | Strongly agree | 31.2 | 14.3 | 187.8 | <0.001 |

| I couldn't cope without cigarettes | Strongly agree | 27.2 | 12.7 | 143.6 | <0.001 |

| There are things which are far worse for me than smoking | Strongly agree | 41.0 | 24.5 | 163.7 | <0.001 |

| If I tried to give up smoking I would probably put on too much weight | Strongly agree | 29.7 | 24.5 | 10.0 | 0.002 |

| I feel more confident in social situations if I have a cigarette | Strongly agree | 22.5 | 15.2 | 13.0 | <0.001 |

| These days smokers are put under too much pressure to give up smoking | Strongly agree | 55.7 | 32.2 | 199.3 | <0.001 |

| People who give up smoking will soon begin to notice their health improving | Strongly agree | 21.8 | 41.4 | 260.5 | <0.001 |

| Doctors are becoming increasingly helpful in supporting smokers who are trying to give up | Strongly agree | 32.1 | 32.0 | 0.024 | 0.88 |

| How likely do you think it is that your smoking will influence whether or not the children in this household become smokers? | Very unlikely | 39.5 | 27.2 | 21.2 | <0.001 |

| How likely do you think it is that your smoking will affect the health of the children who live in this household? | Very likely | 16.8 | 26.3 | 16.1 | <0.001 |

| Do you think that if a child lives with someone who smokes, this increases his or her chance of chest infections? | Yes | 62.0 | 80.8 | 189.7 | <0.001 |

| I smoke in front of my own children or grandchildren | Always | 22.5 | 17.6 | 9.2 | 0.002 |

Hardcore smokers were less tolerant of social pressure to quit (56% v 32% strongly agreed that smokers are now put under too much pressure to quit) and were less prepared to accept that their smoking would have a modelling influence on younger people (40% v 27% thought it very unlikely that their smoking would influence the uptake of smoking by children living in the household).

Differences in attitudes and beliefs by level of dependence

To test whether it was appropriate to exclude a measure of cigarette dependence from our criteria for defining hardcore smoking we compared attitudes and beliefs by dependence in hardcore and other smokers ( table 4). For most items, beliefs were similar in low and high dependence hardcore smokers but strikingly different from those of other smokers. For example, almost 60% of both low and high dependency non-hardcore smokers agreed that improved health would be a major benefit from quitting whereas among hardcore smokers only 27% of low dependency and 32% of high dependency smokers agreed. Similar differentiation in beliefs by hardcore smoking status, but not dependence level, emerged for other items, especially those related to health.

Table 4.

Attitudes towards and beliefs about smoking according to dependence (low or high *) in hardcore and other smokers. Figures are percentage who responded as shown

|

Hardcore

|

Other smokers

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response | Low (390, 4.8%) | High (821, 10.1%) | Low (3071, 37.6%) | High (3446, 42.2%) | |

| How much, if at all, do you think the amount you smoke affects your health now? | Not at all | 39.2 | 30.3 | 14.8 | 11.8 |

| How much, if at all, do you think the amount you smoke will affect your health in the future? | Not at all | 26.0 | 15.0 | 6.3 | 3.9 |

| Improvement of health would be a main advantage of giving up for me personally | Agree | 27.3 | 31.9 | 59.0 | 58.2 |

| I enjoy smoking too much to give it up | Strongly agree | 48.9 | 62.0 | 16.2 | 24.5 |

| I don't think I could give up smoking because I would suffer too much from withdrawal symptoms | Strongly agree | 21.0 | 31.6 | 10.2 | 21.6 |

| Smoking is my main source of pleasure | Strongly agree | 24.1 | 34.6 | 10.0 | 18.2 |

| I couldn't cope without cigarettes | Strongly agree | 18.3 | 31.4 | 6.6 | 18.0 |

| There are things which are far worse for me than smoking | Strongly agree | 42.9 | 40.2 | 23.5 | 25.4 |

| If I tried to give up smoking I would probably put on too much weight | Strongly agree | 21.9 | 33.9 | 20.9 | 27.8 |

| I feel more confident in social situations if I have a cigarette | Strongly agree | 16.5 | 25.6 | 13.6 | 16.8 |

| These days smokers are put under too much pressure to give up smoking | Strongly agree | 50.3 | 58.1 | 26.8 | 37.0 |

| People who give up smoking will soon begin to notice their health improving | Strongly agree | 19.2 | 23.0 | 41.6 | 41.4 |

| Doctors are becoming increasingly helpful in supporting smokers who are trying to give up | Strongly agree | 30.8 | 32.6 | 32.3 | 31.8 |

| How likely do you think it is that your smoking will influence whether or not the children in this household become smokers? | Very unlikely | 46.1 | 36.8 | 27.9 | 26.6 |

| How likely do you think it is that your smoking will affect the health of the children who live in this household? | Very likely | 14.1 | 17.8 | 23.9 | 28.6 |

| Do you think that if a child lives with someone who smokes, then this increases their chance of chest infections? | Yes | 64.6 | 61.0 | 85.2 | 76.9 |

| I smoke in front of my own children or grandchildren | Always | 13.9 | 26.6 | 9.8 | 24.8 |

High=first cigarette within 30 minutes of waking; low=first cigarette after 30 minutes.

Comparison with Californian estimates

Using the same definition of hardcore smoking as adopted in the Californian study, we found a prevalence of 17% across all age groups and 19% among smokers aged ≥ 26 compared with a figure of 5% for this group in the US study. When we added the Californian requirement of ≥ 15 cigarettes a day to our criteria we found a prevalence of 10% among smokers aged ≥ 26, still twice the prevalence in California.

Discussion

Our findings indicate that a substantial minority of cigarette smokers in England have no history of attempting to give up or have had any period of abstinence from smoking and also have no desire or intention to give up in the future. As many as 16% of smokers could be considered hard core by our criteria. There is no generally accepted definition of the construct of hardcore smoking, but our operational definition, which emphasised past behaviour as well as future desires and intentions, was fairly stringent. Our decision to exclude an indicator of dependence was supported by the finding that attitudes and beliefs were generally similar in low and high dependency hardcore smokers but markedly different from other smokers. As expected we found that hardcore smoking was associated with higher levels of nicotine dependence and also increased with socioeconomic deprivation; not surprising in view of the low rate of cessation associated with social disadvantage. 6 But the strongest association was with age.

Age and hardcore smoking

Nearly a third of all smokers aged ≥ 65 scored as hardcore compared with only 5% of smokers in early adulthood. Part of the increase in the proportion of hardcore smokers with age may be due to selective loss from the smoking population of those who are more highly motivated to quit. However, the observed figures go beyond this. Among young adults aged 16-24, some 2% of the whole age group are hardcore smokers (cigarette prevalence of 35%, 8 of whom 5% are hardcore). Among those aged ≥ 65 this figure rises to 5% (cigarette prevalence of 16%, 8 of whom 30% are hardcore). This suggests that the absolute number and not just the proportion of hardcore smokers increases. The implication is that the number of hardcore smokers is not fixed in young adulthood but rises over time, perhaps as dependence increases and a false sense of security develops when years of smoking are perceived not to have affected health. It is, of course, possible that the pattern of hardcore smoking rising with age is only partially attributable to the concentration of resistant smokers increasing. In a cross sectional survey it is not possible to exclude cohort effects that are not connected with cessation.

Older smokers are likely to be especially resistant to stopping smoking. We do not know whether this is through denial of personal risk, the feeling that smoking is too enjoyable and their only pleasure in life, or a feeling that it is too late because the damage is done. All of these could be true, for different smokers. Recent reports indicate that smokers who give up as late as age 65 gain an average of more than two years of additional life expectancy. 9 Campaigns targeted at older smokers and that focus on the substantial personal health gains they stand to make from giving up smoking may be profitable.

Comparison with California

Our estimate of the prevalence of hardcore smoking was much higher than that reported in California. We adopted a different definition of what constitutes hardcore smoking, but even when we used the same definition our estimate was close to four times higher. Why should hardcore smoking be more common in England and what are the implications? There has been an intensive campaign against smoking in California over the past decade or so, resulting in a sharp decline in prevalence to levels that are substantially below those in most other US states as well in the United Kingdom. 10,11 Cigarette smoking prevalence in California in 1997 was 18% 12 compared with 23% in the United States as a whole and 28% in Britain. 8 It is possible that the lower social acceptability of smoking in California has had the effect of moving some smokers who would have been hard core in Britain towards wanting and intending to quit. Whether or not this is true, it is clear that it is not necessarily the case that lowered prevalence will inevitably result in a higher proportion of hardcore smokers as California has both lower cigarette prevalence and a markedly lower proportion of hardcore smokers.

What is already known on this topic

There are concerns that hardcore smoking could become more common as overall cigarette smoking prevalence declines

Some 5% of smokers in California scored as hardcore, but there has been relatively little study of this phenomenon

What this study adds

A total of 16% of English smokers were classified as hardcore

Hardcore smokers tended to be older, more dependent, and from more socioeconomically deprived backgrounds

They were likely to dismiss any effect of smoking on their health

Several other studies have found that older smokers are more recalcitrant in their views than younger smokers 13,14 and more likely to be resistant to giving up. Our findings, which strongly reinforce this conclusion, suggest that the current tendency to be more concerned about cessation in young rather than older smokers is misplaced. The health of older smokers is most imminently at risk and their short term health gains from giving up smoking will be greater.

Progress in reducing smoking related disease will depend on delivering interventions that are targeted to the particular needs and perceptions of both socially disadvantaged and older hardcore smokers.

Contributors: MJJ had the idea for the study, analysed the data, and drafted the paper. J Wardle and J Waller contributed to data analysis and drafting. LO was responsible for designing the questionnaires and the survey methodology, and for overseeing data collection. MJJ is guarantor for this study.

Funding: MJJ, J Wardle, and J Waller are funded by Cancer Research UK. The guarantor accepts full responsibility for the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Warner KE, Burns DM. Hardening and the hardcore smoker: concepts, evidence, and implications. Nicotine Tob Res 2003;5: 37-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute. Those who continue to smoke: Is achieving abstinence harder and do we need to change our interventions? Washington DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No 15) (in press).

- 3.Hughes J. The case for hardening. In: National Cancer Institute. Those who continue to smoke: Is achieving abstinence harder and do we need to change our interventions? San Diego, California: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute (Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No 15) (in press).

- 4.Emery S, Gilpin EA, Ake C, Farkas AJ, Pierce JP. Characterizing and identifying “hardcore” smokers: implications for further reducing smoking prevalence. Am J Public Health 2000;90: 387-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turtle J, Hamlyn B, Lewis D. Smoking in England 1994-1997. London: BMRB International, 1998. (Report No 1153-266.)

- 6.Jarvis MJ. Patterns and predictors of unaided smoking cessation in the general population. In: Bolliger CT, Fagerstrom KO, eds. The tobacco epidemic. Basel: Karger, 1997: 151-64.

- 7.Jarvis MJ, Wardle J. Social patterning of health behaviours: the case of cigarette smoking. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson R, eds. Social determinants of health. Oxford: OUP, 1999: 240-55.

- 8.Thomas M, Walker A, Wilmot A, Bennett N. Living in Britain: Results from the 1996 general household survey. London: Stationery Office, 1998.

- 9.Taylor J, Hasselblad V, Henley S, Thun M, Sloan F. Benefits of smoking cessation for longevity. Am J Public Health 2002;92: 990-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elder JP, Edwards CC, Conway TL, Kenney E, Johnson CA, Bennett ED. Independent evaluation of the California tobacco education program. Pubic Health Rep 1996;111: 353-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegel M, Mowery PD, Pechacek TP, Strauss WJ, Schooley MW, Merritt RK, et al. Trends in adult cigarette smoking in California compared with the rest of the United States, 1978-1994. Am J Public Health 2000;90: 372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bolen J, Rhodes L, Powell-Griner E, Bland S, Holtzman D. State-specific prevalence of selected health behaviors, by race and ethnicity—behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 1997. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 2000;49: 1-60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orleans CT, Jepson C, Resch N, Rimer BK. Quitting motives and barriers among older smokers. The 1986 Adult Use of Tobacco Survey revisited. Cancer 1994;74(7 suppl): 2055-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kviz FJ, Clark MA, Crittenden KS, Freels S, Warnecke RB. Age and readiness to quit smoking. Prev Med 1994;23: 211-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]