Abstract

PURPOSE: This study was designed to estimate the prevalence of, and identify risk factors associated with, fecal incontinence in racially diverse females older than aged 40 years. METHODS: The Reproductive Risks for Incontinence Study at Kaiser is a population-based study of 2,109 randomly selected middle-aged and older females (average age, 56 years). Fecal incontinence, determined by self-report, was categorized by frequency. Females reported the level of bother of fecal incontinence and their general quality of life. Potential risk factors were assessed by self-report, interview, physical examination, and record review. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the independent association between selected risk factors and the primary outcome of any reported fecal incontinence in the past year. RESULTS: Fecal incontinence in the past year was reported by 24 percent of females (3.4 percent monthly, 1.9 percent weekly, and 0.2 percent daily). Greater frequency of fecal incontinence was associated with decreased quality of life (Medical Outcome Short Form-36 Mental Component Scale score, P = 0.01), and increased bother (P < 0.001) with 45 percent of females with fecal incontinence in the past year and 100 percent of females with daily fecal incontinence reporting moderate or great bother. In multivariate analysis, the prevalence of fecal incontinence in the past year increased significantly [odds ratio per 5 kg/m2 (95 percent confidence interval)] zwith obesity [1.2 (1.1–1.3)], chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [1.9 (1.3–2.9)], irritable bowel syndrome [2.4 (1.7–3.4)], urinary incontinence [2.1 (1.7–2.6)], and colectomy [1.9 (1.1–3.1)]. Latina females were less likely to report fecal incontinence than white females [0.6 (0.4–0.9)]. CONCLUSIONS: Fecal incontinence, a common problem for females, is associated with substantial adverse affects on quality of life. Several of the identified risk factors are preventable or modifiable, and may direct future research in fecal incontinence therapy.

Keywords: Fecal incontinence, Epidemiology, Risk factors, Prevalence

Fecal incontinence (FI) results in significant physical and psychologic disability. Many people with FI suffer from ongoing depression, social isolation, and work absenteeism because they are too embarrassed to discuss the problem with their health care providers and, therefore, are unaware of available treatments.1-3 Despite a number of existing studies, more research is needed to better understand the prevalence, impact, and risk factors of this condition among females in the United States.

The reported prevalence of FI has varied considerably depending on the provenance of the population studied, and definition of incontinence used. In clinic-based studies, such as general medicine or gynecology, the reported prevalence has varied from 2 to 18 percent,4-7 whereas studies in nursing homes have reported a higher prevalence, from 10 to 47 percent.8,9 The higher estimates in gynecology clinics and nursing homes are consistent with common assumptions regarding females, the elderly, and the infirm being disproportionately affected by the condition. In population-based samples, the prevalence has been reported to be 2 to 12 percent depending on the age of the cohort.1,3,5,10,11 Those studies that included males and females demonstrated fairly equal gender distribution, although most patients seeking treatment are females.12 Only two population-based studies to date have reported on prevalence by race/ethnicity; both focused on whites and African-Americans and found no significant differences in prevalence based on race.10,11 Furthermore, there is no standardized definition of fecal incontinence, either by type of loss (liquid, mucous, solid stool) or time frame of loss (never, previous 12 months, previous month, etc.), and few studies have examined prevalence based on type and frequency of incontinence, making it difficult to assess the severity of the problem.

Fecal incontinence is known to have a profound effect on quality of life. Many people are unable to socialize or participate in activities outside the home because of their need to maintain close access to a toilet. Research has shown that physical, psychologic, and social functioning of patients are affected, and FI results in a poorer perception of overall health.10,13,14 However, what is not well described is whether the impact or burden of the condition varies by frequency of incontinence or the population sampled.

Studies examining independent risk factors predictive of fecal incontinence have implicated age, obstetric and gynecologic factors, several medical conditions, and poor health.1,4,5,10,11 In particular, age, parity, vaginal delivery, diabetes, diarrhea, and neurologic conditions have been notably associated. However, some of these factors have been reported in only one study. Furthermore, these studies, and others that only used univariate analysis, have been difficult to interpret because of poor definitions of incontinence, lack of measurement of frequency of incontinence, and possible confounding factors, such as age, body mass index, parity, and common medical conditions not being included in the analysis.

Ascertaining the prevalence of fecal incontinence in a racially diverse general population of females by frequency and impact on quality of life is critical to fully understand the scope of this condition for females in the United States. Because many risk factors that have been associated with FI are related, it also is important to examine whether these risk factors are independently associated with FI. Therefore, we examined a racially diverse, population-based cohort of middle-aged and older females to estimate the prevalence of fecal incontinence by frequency, associated level of bother, and impact on quality of life. In addition, we sought to identify independent risk factors associated with fecal incontinence in our cohort.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

From October 1999 through February 2003, 2,109 community-dwelling females were enrolled in the Reproductive Risks for Incontinence Study at Kaiser (RRISK), a population-based, racially diverse cohort of middle-aged and older females. The study cohort was constructed by identifying females between age 40 and 69 years who, since age 18, had been members of the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California (KPMCP), a large integrated health care delivery system with >3 million members, which serves approximately 25 percent of the population in the area. Although previous studies have found KPMCP members to underrepresent extremes in economic status and to be slightly more educated, members have been shown to be similar to the population in the geographic area served with respect to all other demographic characteristics.15 From a group of approximately 66,000 long-term female members, a sample of 10,230 females was randomly selected within age and race strata, with a goal of obtaining approximately equal numbers of females in each five-year age group with a race/ethnicity composition of 20 percent African–American, 20 percent Latina, 20 percent Asian–American, and 40 percent white (non-Hispanic). After the determination of eligibility, which included having at least one-half of all births at Kaiser, 2,109 females were enrolled and comprise the sample for this cross-sectional study. Details of the recruitment have been separately reported.16

Data on fecal incontinence were collected by self-report questionnaires. Fecal incontinence was assessed by the question “During the last 12 months, how often have you experienced leakage of stool (bowel movements), accidents, or soiling because of inability to control passage of stool (bowel movements) until you reach the toilet?” Frequency was reported as daily, weekly, monthly, less than monthly, or never in the past year. Prevalence of fecal incontinence by frequency of loss was estimated. Because the number of females with daily fecal incontinence was small (n = 4), the daily and weekly groups were combined (hereafter identified as the “weekly” group). Only females who reported any stool leakage were asked to report whether they were bothered by leakage (“not at all,” “slightly,” “moderately,” or “greatly”). Flatal incontinence was assessed by the question “During the last 12 months, how often have you experienced leakage of gas (unexpected or embarrassing loss of control of gas)?” with frequency reported as daily, weekly, monthly, less than monthly, or never in the past year. We analyzed data from 2,106 of 2,109 females enrolled in the study who responded to questions regarding fecal incontinence.

Factors potentially associated with fecal incontinence were assessed by questionnaire, interview, medical record review, and physical examination. Participants completed an in-person interview with a structured questionnaire, which included questions about age, race/ethnicity, demographic characteristics (education, employment, and income level), reproductive and menopause history (parity, menopausal status, current oral estrogen use), presence of selected medical conditions (diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), irritable bowel syndrome, and inflammatory bowel disease), previous surgeries (hysterectomy, pelvic organ prolapse repair (i.e., for cystocele, rectocele, uterine, or vaginal prolapse), appendectomy, colectomy, and cholecystectomy), and general health status. Other pelvic floor disorders were assessed by self-report of urinary incontinence (“During the last 12 months, have you leaked urine, even a small amount?”) or pelvic organ prolapse (ever having “dropped or prolapsed female/pelvic organs (bladder, uterus, vagina, rectum)”). Quality of life was assessed by the Medical Outcome Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) from which a standardized mental component scale (SF-36 MCS) and physical component scale (SF-36 PCS) were calculated.17 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated (kg/m2) based on the participant's weight and height measured at the time of the interview. Method of delivery (vaginal or cesarean section) was abstracted from review of labor and delivery and surgical medical records archived since 1946 and categorized as none, at least one cesarean section, or only vaginal delivery(ies).

In our primary analysis, we used multivariate logistic regression models to control for potential confounding variables and to determine the independent associations between risk factors identified a priori and fecal incontinence. Because the occurrence of any fecal incontinence in a population-based cohort of females was believed to be clinically important, females who reported any fecal incontinence in the last 12 months (fecal incontinence) were compared with females with no fecal incontinence in the last 12 months (no fecal incontinence). Variables associated (P ≤ 0.2) with fecal incontinence in univariate models that remained significant at this level after adjustment were retained in the final multivariate models. Results are presented as odds ratios (OR) and 95 percent confidence intervals (95 percent CI). Use of a logistic regression model with a dichotomous outcome of any vs. no fecal incontinence provided a clearer presentation of independent risk factors for fecal incontinence. Additional analyses using a proportional odds model18 were performed to examine frequency of fecal incontinence as an ordinal variable using the categories of never in the past year, less than monthly, monthly, weekly, or more frequently. Similar significant associations to fecal incontinence were found by using both logistic and ordinal models. In a separate analysis, we compared frequency of incontinence to degree of bother. Multivariable linear models using analogous criteria for the selection of covariates were used to assess fecal incontinence frequency as a predictor of quality of life, assessed by scores on the SF-36 MCS and PCS scales; linear contrasts in the coefficients were used to test for trends across frequency categories. Results of this model are presented as adjusted mean scores for each frequency category, with 95 percent confidence intervals. All analyses were performed in SAS Version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The mean (±standard deviation) age of this cohort was 55.9 ± 8.6 years and participants were racially diverse (48 percent white, 18 percent African–American, 17 percent Latina, and 16 percent Asian; Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Reproductive Risks for Incontinence Cohort (RRISK) by Frequency of Fecal Incontinence

| Risk Factor | Overall (N = 2,106) | No Fecal Incontinencea (n = 1,595) | Fecal Incontinenceb (n = 511) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age category (yr) | <0.001 | |||

| 40–49 | 598 (28) | 492 (82) | 106 (18) | |

| 50–59 | 796 (38) | 603 (76) | 193 (24) | |

| 60–69 | 553 (26) | 393 (71) | 160 (29) | |

| ≥70 | 159 (8) | 107 (67) | 52 (33) | |

| Race | 0.0195 | |||

| White | 1,002 (48) | 730 (73) | 272 (27) | |

| African–American | 383 (18) | 294 (77) | 89 (23) | |

| Asian | 344 (16) | 267 (78) | 77 (22) | |

| Latina | 349 (17) | 284 (81) | 65 (19) | |

| Native American/other | 28 (1) | 20 (71) | 8 (29) | |

| Education | 0.7664 | |||

| HS or less | 64 (3) | 52 (81) | 12 (19) | |

| HS/some college | 1,304 (62) | 987 (76) | 317 (24) | |

| Bachelor/some grad | 472 (22) | 356 (75) | 116 (25) | |

| Grad/professional school | 265 (13) | 199 (75) | 66 (25) | |

| Job status | <0.001 | |||

| Employed/student | 1,367 (65) | 1,072 (78) | 295 (22) | |

| Unemployed/other | 97 (5) | 66 (68) | 31 (32) | |

| Retired | 501 (24) | 341 (68) | 160 (32) | |

| Homemaker | 139 (7) | 114 (82) | 25 (18) | |

| Income ($) | 0.0011 | |||

| <40,000 | 471 (24) | 327 (69) | 144 (31) | |

| 40,000–79,999 | 845 (43) | 659 (78) | 186 (22) | |

| ≥80,000 | 631 (32) | 489 (77) | 142 (23) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <0.001 | |||

| <25 | 717 (34) | 583 (81) | 134 (19) | |

| 25 to <30 | 658 (31) | 490 (74) | 168 (26) | |

| 30 to <35 | 389 (19) | 292 (75) | 97 (25) | |

| 35 to <40 | 195 (9) | 132 (68) | 63 (32) | |

| ≥40 | 135 (6) | 88 (65) | 47 (35) | |

| Health conditions and habits | ||||

| Self-reported health status | <0.001 | |||

| Excellent | 362 (17) | 299 (83) | 63 (17) | |

| Very good/good | 1,501 (71) | 1,139 (76) | 362 (24) | |

| Fair/poor | 243 (12) | 157 (65) | 86 (35) | |

| Diabetes | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 174 (8) | 113 (65) | 61 (35) | |

| No | 1,932 (92) | 1,482 (77) | 450 (23) | |

| COPD | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 123 (6) | 73 (59) | 50 (41) | |

| No | 1,983 (94) | 1,522 (77) | 461 (23) | |

| IBS | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 204 (10) | 113 (55) | 91 (45) | |

| No | 1,902 (90) | 1,482 (78) | 420 (22) | |

| IBD | 0.0671 | |||

| Yes | 22 (1) | 13 (59) | 9 (41) | |

| No | 2,084 (99) | 1,582 (76) | 502 (24) | |

| Any cancer historyc | 0.0874 | |||

| Yes | 191 (9) | 135 (71) | 56 (29) | |

| No | 1,915 (91) | 1,460 (76) | 455 (24) | |

| Current smoker | 0.441 | |||

| Yes | 212 (10) | 156 (74) | 56 (26) | |

| No | 1,894 (90) | 1,439 (76) | 455 (24) | |

| Reproductive history | ||||

| Parity/delivery type | 0.0196 | |||

| None | 385 (19) | 308 (80) | 77 (20) | |

| C-section only | 116 (6) | 95 (82) | 21 (18) | |

| At least one vaginal | 1,523 (75) | 1,132 (74) | 391 (26) | |

| Postmenopausal | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1,377 (67) | 987 (72) | 390 (28) | |

| No | 684 (33) | 573 (84) | 111 (16) | |

| Current estrogen use | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 650 (31) | 459 (71) | 191 (29) | |

| No | 1,456 (69) | 1,136 (78) | 320 (22) | |

| Pelvic floor dysfunction | ||||

| Urinary incontinence | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 602 (29) | 383 (64) | 219 (36) | |

| No | 1,504 (71) | 1,212 (81) | 292 (19) | |

| Pelvic organ prolapse | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 159 (8) | 99 (62) | 60 (38) | |

| No | 1,947 (92) | 1,496 (77) | 451 (23) | |

| UTI ≥ 1 in past year | 0.2692 | |||

| Yes | 263 (12) | 192 (73) | 71 (27) | |

| No | 1,843 (88) | 1,403 (76) | 440 (24) | |

| Surgery | ||||

| Hysterectomy | 0.015 | |||

| Yes | 474 (23) | 339 (72) | 135 (28) | |

| No | 1,632 (77) | 1,256 (77) | 376 (23) | |

| Other pelvic surgery | 0.0326 | |||

| Yes | 981 (47) | 722 (74) | 259 (26) | |

| No | 1,125 (53) | 873 (78) | 252 (22) | |

| POP surgery | 0.0072 | |||

| Yes | 75 (4) | 47 (63) | 28 (37) | |

| No | 2,031 (96) | 1,548 (76) | 483 (24) | |

| Colon surgery | 0.0012 | |||

| Yes | 78 (4) | 47 (60) | 31 (40) | |

| No | 2,028 (96) | 1,548 (76) | 480 (24) | |

| Appendectomy | 0.177 | |||

| Yes | 378 (18) | 276 (73) | 102 (27) | |

| No | 1,726 (82) | 1,317 (76) | 409 (24) | |

| Cholecystectomy | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 222 (11) | 143 (64) | 79 (36) | |

| No | 1,881 (89) | 1,450 (77) | 431 (23) |

Data are numbers with percentages in parentheses unless otherwise indicated. Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

HS = high school; grad = graduate school; BMI = body mass index; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IBS = irritable bowel syndrome; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; UTI = urinary tract infection; POP = pelvic organ prolapse.

No fecal incontinence reported in the last 12 months.

Any fecal incontinence reported in the last 12 months.

Excluding non-melanomatous skin cancer.

The prevalence of medical conditions ranged from 1 percent (inflammatory bowel disease) to 10 percent (irritable bowel syndrome). Seventy-five percent of females had at least one vaginal delivery, 29 percent reported at least weekly urinary incontinence, and 8 percent reported pelvic organ prolapse.

Nearly one-fourth of females reported fecal incontinence in the previous 12 months and 5.5 percent reported at least monthly fecal incontinence (Table 2). Weekly flatal incontinence was reported by >15 percent of females and daily flatal incontinence by 9 percent. Of note, 40 percent of females reporting fecal incontinence in the past year also reported at least weekly flatal incontinence.

Table 2.

Frequency of Fecal and Flatal Incontinence

| Total | No Incontinence | Less Than Monthly | Monthly | More Than Weekly | Daily | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fecal incontinence | 2,106 | 1,595 (76) | 395 (19) | 71 (3) | 41 (2) | 4 (<1) |

| Flatal incontinence | 2,101 | 609 (29) | 707 (34) | 292 (14) | 307 (15) | 186 (9) |

Data are numbers with percentages in parentheses.

No incontinence = no reported incontinence in the past 12 months; Less than monthly = at least one incontinent episode per year but not monthly; Monthly = at least one incontinent episode per month but not weekly; Weekly = at least one incontinent episode per week but not daily.

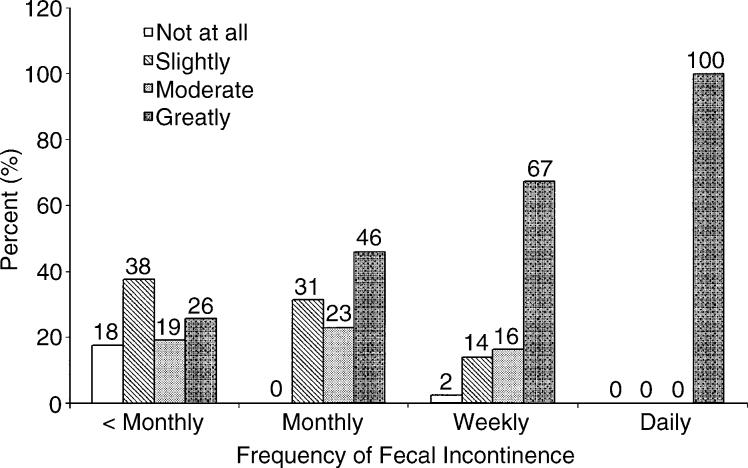

Frequency of fecal incontinence is highly correlated with both females' self-reported quality of life and level of bother about their fecal incontinence (Table 3 and Fig. 1). In unadjusted models, higher frequencies of fecal incontinence were associated with lower SF-36 scores for both the physical (PCS; P < 0.006) and mental (MCS; P < 0.02) health component scales (Table 3). In models adjusting for variables associated with SF-36 MCS and SF-36 PCS scores, a lower SF-36 score was independently associated with an increasing frequency of fecal incontinence (P < 0.01). Increasing frequency of fecal incontinence was also associated with increased bother (Fig. 1; P < 0.001 by the Mantel–Haenszel chi-squared (a transformation of the Spearman rank-correlation coefficient)). More than 45 percent of females with fecal incontinence in the past year reported that they are moderately or greatly bothered by the condition, and 100 percent of females with daily fecal incontinence report that they are greatly bothered. Level of bother of fecal incontinence was not associated with SF-36 MCS or PCS scores (P = 0.2 and P = 0.29, respectively, by chi-squared analysis).

Table 3.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Quality of Life by Frequency of Fecal Incontinence

| No Incontinence | Less Than Monthly | Monthly | More Than Weekly | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF-36 MCS | |||||

| Unadjusted | 44.7 (44.4, 45) | 43.9 (43.3, 44.5) | 43.9 (42.4, 45.4) | 42.2 (40.2, 44.3) | 0.006 |

| Adjustedb | 44.7 (44.5, 45) | 43.8 (43.3, 44.4) | 44.3 (43, 45.6) | 42.2 (40.5, 43.9) | 0.01 |

| SF-36 PCS | |||||

| Unadjusted | 46.5 (46.2, 46.8) | 44.8 (44.1, 45.4) | 42.7 (40.8, 44.6) | 44.9 (42.8, 47.1) | 0.02 |

| Adjustedc | 46.1 (45.9, 46.4) | 45.7 (45.2, 46.2) | 45.5 (44.3, 46.7) | 47 (45.4, 48.5) | 0.36 |

Data are means with 95 percent confidence intervals in parentheses unless otherwise indicated (SF-36 scoring: the MCS and PCS are scored from 0 to100, with increasing score for increasing quality of life; No incontinence = no reported fecal incontinence in the past 12 months; Less than monthly = at least 1 fecal incontinent episode per year but not monthly; Monthly = at least 1 fecal incontinent episode per month but not weekly; Weekly = at least 1 incontinent episode per week).

SF-36 MCS = Medical Outcome Short Form-36 Mental Component Score; SF-36 PCS = Medical Outcome Short Form-36 Physical Component Score.

P values are based on tests for trend.

Adjusted for race, age, body mass index, self-reported health status, irritable bowel syndrome, current smoker, menopause status, pelvic organ prolapse, ≥1 urinary tract infection in the past year and pelvic organ prolapse surgery.

Adjusted for race, age, body mass index, self-reported health status, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, irritable bowel syndrome, weekly urinary incontinence, ≥1 urinary tract infection in the past year, pelvic organ prolapse surgery and cholecystectomy.

Figure 1.

Females' level of bother of fecal incontinence by frequency of fecal incontinence. Numbers above each bar are the percentage of females reporting each level of bother within each fecal incontinence frequency group. There is a significant linear association between frequency of incontinence and bother (P < 0.001). < Monthly = at least one fecal incontinent episode per year but not monthly; Monthly = at least one fecal incontinent episode per month but not weekly; Weekly = at least one incontinent episode per week.

The univariate analyses of factors potentially associated with any fecal incontinence in the past year indicate that increasing age was associated with increasing prevalence of fecal incontinence (P < 0.001; Table 1). Compared with 18 percent of females in the 40- to 49-year-old age group, >30 percent of females older than aged 70 years reported any fecal incontinence. The prevalence of fecal incontinence also varied by race/ethnicity: from 19 percent of Latina females to 29 percent of Native American females (P < 0.02). When adjusted for age, race did not affect the prevalence of fecal incontinence (results not shown, P = 0.27). Obesity also was associated with increasing prevalence of fecal incontinence (P < 0.001), with 19 percent of females with a BMI < 25 kg/m2 compared with 35 percent of females with BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 reporting any fecal incontinence.

All variables that were associated with fecal incontinence (P < 0.2; Table 1) in univariate analyses were included in a multivariate model comparing females reporting any fecal incontinence in the past year to those with no fecal incontinence (Table 4). Factors independently associated with a higher prevalence of fecal incontinence in the past year were obesity (20 percent greater for each 5-unit increase in BMI), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (90 percent increase), irritable bowel syndrome (2.4-fold increase), weekly or greater urinary incontinence (2-fold increase), and colectomy (90 percent increase). The prevalence of reporting fecal incontinence was 40 percent lower among Latina females than among non-Latina white females (P < 0.04).

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis of Factors Independently Associated With Fecal Incontinence in the Past 12 Months

| Odds Ratio | Stratum | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 5 yr) | 1.1 | 1–1.2 | 0.15 | |

| Race (vs. white) | African–American | 0.9 | 0.7–1.3 | 0.03 |

| Asian | 1.2 | 0.9–1.6 | ||

| Latina | 0.6 | 0.4–0.9 | ||

| Native American | 1.2 | 0.5–3 | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m2, per 5 units) | 1.2 | 1.1–1.3 | 0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 1.4 | 1–2.1 | 0.07 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1.9 | 1.3–2.9 | 0.002 | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 2.4 | 1.7–3.4 | <0.001 | |

| Parity (vs. none) | C-section | 1 | 0.5–1.7 | 0.22 |

| At least one vaginal birth | 1.3 | 0.9–1.7 | ||

| Postmenopausal | 1.4 | 1–2 | 0.05 | |

| Current estrogen use | 1.3 | 1–1.7 | 0.05 | |

| Urinary incontinence | 2.1 | 1.7–2.6 | <0.001 | |

| Pelvic organ prolapse surgery | 1.4 | 0.9–2 | 0.12 | |

| Hysterectomy | 0.7 | 0.6–1 | 0.05 | |

| Colectomy | 1.9 | 1.1–3.1 | 0.02 | |

| Cholecystectomy | 1.4 | 1–1.9 | 0.07 |

Age, previous vaginal delivery, health status, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic organ prolapse, hysterectomy, cholecystectomy, and surgery for pelvic organ prolapse were not independently associated with reporting fecal incontinence in the past year. Currently using estrogen and being postmenopausal were each associated with a 30 to 40 percent increase and having had a hysterectomy was associated with a 30 percent decrease in prevalence of fecal incontinence (all P = 0.05).

When analyses were repeated comparing females with monthly or greater fecal incontinence to those without fecal incontinence, additional independent risk factors were identified: age (OR, 1.2 for each 5 years of age; 95 percent CI, 1.1–1.4), diabetes (OR, 2.3; 95 percent CI, 1.3–4), parity (OR, 3.5, 95 percent CI, 1.1–11.2 for cesarean section only vs. no delivery; OR, 3.2, 95 percent CI, 1.4–7.3 for ≥1 vaginal delivery vs. no delivery), and cholecystectomy (OR, 2.1; 95 percent CI, 1.3–3.5).

When proportional odds models were used to examine factors independently associated with increasing frequency of fecal incontinence as an ordinal categoric variable, the results were similar to the multivariate analysis of factors associated with any fecal incontinence in the past year. Specifically, obesity, COPD, diabetes, irritable bowel syndrome, weekly or greater urinary incontinence, colectomy, and cholecystectomy were positively associated with increasing frequency of fecal incontinence (data not shown). Latina females had a significant negative association to increasing frequency of fecal incontinence compared with white females.

DISCUSSION

Among this cohort of 2,106 racially diverse females, fecal incontinence was found to be as common as many chronic medical conditions. Nearly one-quarter of females in this cohort reported fecal incontinence in the previous year with nearly 6 percent reporting at least monthly fecal incontinence. Almost one-half of the females with monthly fecal incontinence were moderately or greatly bothered by it, and all females with daily fecal incontinence reported that they were greatly bothered by their condition. Even for females with infrequent fecal incontinence (less than monthly), nearly one-quarter of females had a high level of bother. In addition, fecal incontinence was independently associated with diminished general quality of life, with a greater impact on mental health compared with physical health. Flatal incontinence was much more common than fecal incontinence, with almost three times as many females reporting leakage of gas. The loss of gas, which often is included in studies of anal incontinence, needs to be examined further because the prevalence, frequency, quality of life, and level of bother of flatal incontinence are poorly defined.

The diversity of our large population-based RRISK cohort provides a unique opportunity to examine differences in fecal incontinence among four major racial/ethnic groups within one study. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first population-based study to ascertain fecal incontinence that includes all major racial/ethnic groups, and thereby avoids the problems inherent in comparing fecal incontinence prevalence across studies. We found that Latina females reported the lowest prevalence, followed by Asian–American, African–American, and non-Latina white females. Latina females remained at the lowest risk for fecal incontinence, even after we adjusted for common risk factors. Interestingly, in the RRISK cohort, Latina females had the highest prevalence of weekly or greater urinary incontinence, followed by white, African–American, and Asian–American females (36, 30, 25, and 19 percent, respectively, P < 0.001).16 The decreased prevalence of FI and increased prevalence of urinary incontinence in Latinas could be a result of reporting bias or other unmeasured factors not included in our analysis. Future studies of prevalence using larger sized Latina populations and anorectal physiology studies pertaining to FI in Latinas may further clarify this new finding. Unfortunately, most studies to date have not addressed issues of race and ethnicity and, therefore, data are limited.1,3-6,19 Two studies comparing the prevalence of fecal incontinence between racial/ethnic groups have evaluated only whites vs. African–Americans, and observed no significant difference in prevalence.10,11 The etiology of fecal incontinence may be better understood with studies that investigate if there are any racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of and risk factors for fecal incontinence.

We identified several other independent risk factors for fecal incontinence in the previous year, including obesity, COPD, irritable bowel syndrome, urinary incontinence, and colectomy. In addition, when we examined factors independently associated with monthly or more frequent fecal incontinence, age, diabetes, parity, and cholecystectomy also were significant. These risk factors likely contribute to FI via multiple mechanisms: anatomic, neurologic, congenital, and functional.12 Mechanistically, fecal incontinence results from an imbalance of the propulsive forces of stool with the resistive mechanisms of the pelvis. Associations of certain conditions with increased abdominal pressure (obesity and coughing related to COPD), increased intestinal motility or loose stool (irritable bowel syndrome, diabetes, colectomy, cholecystectomy), and sphincter or pelvic floor weakness from an anatomic defect or nerve damage (age, parity, diabetes) may all contribute to fecal incontinence.

Increased abdominal pressure is a potential mechanism for the increased FI seen with obesity and COPD. The association of FI with increasing obesity has been described in previous studies4,20; however, the wide range of BMI in this study allows for more precise estimates of its independent association. We postulate that excess weight increases abdominal and pelvic pressure both at rest and with exertion, which in turn damages pelvic floor support, leading to FI. It is unknown whether this effect is reversible. Independent of smoking, COPD was associated with a nearly twofold higher odds of FI. It is possible that chronic cough caused by COPD also increases pelvic pressure and damages the pelvic floor structures in a similar way as obesity.

Liquid stool associated with increased intestinal motility has been observed by others as an independent predictor of fecal incontinence.10 Diarrhea has been noted in patients with diabetes,21-23 irritable bowel syndrome,24 and those who have had previous cholecystectomy25 or colectomy.26 Previous studies of FI have examined associations with diabetes and irritable bowel syndrome,4,11,23 and our study additionally found cholecystectomy and colectomy to be associated with FI. If the diarrhea and increased motility associated with these conditions could be treated, it might be possible to decrease the frequency of or eliminate FI in these patients.

Theoretically, weakness of the pelvic floor muscles and support associated with advancing age and parity may impair the resistive forces of the pelvis that prevent leakage of stool. Although some studies have reported that age1,4 and parity5 are independently associated with fecal incontinence, our study did not. Whereas vaginal delivery often is considered a risk factor for fecal incontinence, it did not remain one in our multivariate analysis. Additionally, both cesarean section and vaginal delivery were associated with monthly or more frequent incontinence in our study, indicating that parity, and perhaps labor, are risk factors, not mode of delivery. The association of vaginal delivery with incontinence was weaker in our study than in others,5,27 probably because we adjusted for multiple related factors, such as age and other medical conditions.

Urinary incontinence was an independent risk factor for fecal incontinence in this study. Other studies also have shown this association, leading investigators to believe that urinary and fecal incontinence share etiologic factors, including damage to the pelvic floor as a result of pregnancy and childbirth.10,20,28 Therefore, urinary incontinence may be a marker for pelvic floor damage and dysfunction rather than a cause of fecal incontinence. This underscores the importance of asking patients with fecal or urinary incontinence whether they experience symptoms of the other condition.

Hysterectomy, estrogen use, and menopause also were found to be independently associated with fecal incontinence. Findings on the association of hysterectomy with fecal incontinence are inconsistent in studies using multivariate analysis. Although we observed a decreased risk of fecal incontinence in females with a hysterectomy, another study found a significant increased risk of fecal incontinence after hysterectomy with oophorectomy (OR, 1.93; 95 percent CI, 1.06–3.54)10 and one study reported no association with hysterectomy.4 Females currently using estrogens were at a 30 percent increased risk of fecal incontinence. Only one study examining estrogen replacement therapy demonstrated no association in a univariate analysis.6 Recent, large, randomized trials of hormone therapy in females with urinary incontinence have found that standard doses of oral estrogen, with or without progestin, worsen urinary incontinence.29,30 A number of mechanisms for increased urinary incontinence have been suggested, including increased collagen breakdown and subsequent decreased periurethral collagen,31 and increased loose, vascular connective tissue layer of the urethra.32 Similar mechanisms may affect the rectal sphincter, resulting in fecal incontinence. When females are considering hormone therapy, they should be informed of the potential increased risk of fecal incontinence. Similarly, our finding of increased risk of fecal incontinence in postmenopausal females has not been observed in other studies, begging the inclusion of these variables in future studies of risk factors for fecal incontinence.

Finally, diabetes may contribute to fecal incontinence through neurologic and microvascular pathways. We found diabetes to be associated with a 40 percent increased risk of fecal incontinence. Previous studies also have found diabetes to increase risk for fecal incontinence.11,23 Microvascular complications associated with diabetes may damage the innervation of the rectum and pelvic floor musculature. In addition, acute hyperglycemic episodes inhibit external sphincter function and diminished rectal compliance, which can potentially exacerbate fecal incontinence.33

Several of these risk factors for fecal incontinence are potentially preventable and/or modifiable: obesity, COPD, diabetes, and irritable bowel syndrome. Management of diarrhea is a standard first line of therapy for fecal incontinence.34 Additional treatment and control of irritable bowel syndrome or diabetes and intervention for weight loss and coughing associated with COPD also may affect fecal incontinence. Identifying preventable and modifiable risk factors may guide future research for prevention or treatment of fecal incontinence. Furthermore, females with fecal incontinence should be assessed for any medical conditions that are associated with fecal incontinence because treatment of these conditions may secondarily affect symptoms of incontinence.

Our study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the study is cross-sectional and thus cannot determine causal associations. Second, as in previous large epidemiologic studies, fecal incontinence was defined by self-report without specifying the consistency of stool lost or using any other characteristics that may help to define severity. Unfortunately, there are as yet no standardized definitions for severity of incontinence, which has had a significant impact on research in this field. A scoring system needs to be developed that can assign a numeric value to important variables that define incontinence, such as consistency of stool, frequency of loss, the presence of urgency, and the need for pads or diapers. A third limitation is that quality of life was measured by the SF-36, a commonly used instrument14 that is not incontinence specific, and by a question of bother. A recently validated fecal incontinence-specific quality of life instrument, the Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life instrument (FIQL), measures four areas (lifestyle, coping/behavior, depression/self-perception, and embarrassment) and is more sensitive than symptom-nonspecific scales for fecal incontinence.35 However, our study is the first to adjust the analyses of quality of life for other medical conditions that may have confounded the results. Finally, the participants in the study were generally healthy, community-dwelling volunteers who were long-term members of a large prepaid health delivery system. Before initiating the study, we determined that females who were Kaiser members since age 18 years were similar to all female members of the same age with respect to multiple characteristics, including the number of office visits in the past 27 months to gynecology, urology, and family practice/internal medicine clinics, previous hysterectomies, and use of hormone replacement therapy. However, this aspect of our study should be considered when generalizing our results to other populations.

CONCLUSIONS

Fecal incontinence affects almost 25 percent of community-dwelling females. Thus, fecal incontinence is more common than most medical conditions. In addition, it has a profound impact on quality of life and is greatly bothersome. Several of the risk factors for fecal incontinence are preventable or modifiable. These conditions should be considered when planning future research for fecal incontinence therapy.

Footnotes

The Reproductive Risk of Incontinence Study in Kaiser (RRISK) was funded by the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant # R01-DK53335.

Presented at the meeting of The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, April 30 to May 5, 2005.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nelson R, Norton N, Cautley E, Furner S. Community-based prevalence of anal incontinence. JAMA. 1995;274:559–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakanishi N, Tatara K, Shinsho F, et al. Mortality in relation to urinary and faecal incontinence in elderly people living at home. Age Ageing. 1999;28:301–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/28.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boreham MK, Richter HE, Kenton KS, et al. Anal incontinence in women presenting for gynecologic care: prevalence, risk factors, and impact upon quality of life. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1637–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faltin DL, Sangalli MR, Curtin F, Morabia A, Weil A. Prevalence of anal incontinence and other anorectal symptoms in women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12:117–20. doi: 10.1007/pl00004031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gordon D, Groutz A, Goldman G, et al. Anal incontinence: prevalence among female patients attending a urogynecologic clinic. Neurourol Urodyn. 1999;18:199–204. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6777(1999)18:3<199::aid-nau6>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johanson JF, Lafferty J. Epidemiology of fecal incontinence: the silent affliction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:33–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tobin GW, Brocklehurst JC. Faecal incontinence in residential homes for the elderly: prevalence, aetiology and management. Age Ageing. 1986;15:41–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/15.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson R, Furner S, Jesudason V. Fecal incontinence in Wisconsin nursing homes: prevalence and associations. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1226–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02258218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goode PS, Burgio KL, Halli AD, et al. Prevalence and correlates of fecal incontinence in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:629–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quander CR, Morris MC, Melson J, Bienias JL, Evans DA. Prevalence of and factors associated with fecal incontinence in a large community study of older individuals. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:905–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.30511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Madoff RD, Parker SC, Varma MG, Lowry AC. Faecal incontinence in adults. Lancet. 2004;364:621–32. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16856-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Byrne CM, Pager CK, Rex J, Roberts R, Solomon MJ. Assessment of quality of life in the treatment of patients with neuropathic fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:1431–6. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6444-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothbarth J, Bemelman WA, Meijerink WJ, et al. What is the impact of fecal incontinence on quality of life? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:67–71. doi: 10.1007/BF02234823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:703–10. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.5.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thom DH, Van Den Eeden SK, Ragins AI, et al. Differences in prevalence of urinary incontinence by race/ethnicity. J Urol. 2006;175:259–64. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00039-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCullagh P, Nelder JA. Generalized linear models. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nygaard IE, Rao SS, Dawson JD. Anal incontinence after anal sphincter disruption: a 30-year retrospective cohort study. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:896–901. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uustal Fornell E, Wingren G, Kjolhede P. Factors associated with pelvic floor dysfunction with emphasis on urinary and fecal incontinence and genital prolapse: an epidemiological study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:383–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lysy J, Israeli E, Goldin E. The prevalence of chronic diarrhea among diabetic patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2165–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson RL. Epidemiology of fecal incontinence (1 Suppl 1) Gastroenterology. 2004;126:S3–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with diabetes mellitus: a population-based survey of 15,000 adults. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1989–96. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.16.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guilera M, Balboa A, Mearin F. Bowel habit subtypes and temporal patterns in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1174–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauter GH, Moussavian AC, Meyer G, Steitz HO, Parhofer KG, Jungst D. Bowel habits and bile acid malabsorption in the months after cholecystectomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1732–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ho YH, Low D, Goh HS. Bowel function survey after segmental colorectal resections. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:307–10. doi: 10.1007/BF02049473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLennan AH, Taylor AW, Wilson DH, Wilson D. The prevalence of pelvic floor disorders and their relationship to gender, age, parity and mode of delivery. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2000;107:1460–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb11669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lacima G, Pera M. Combined fecal and urinary incontinence: an update. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003;15:405–10. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200310000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grady D, Brown JS, Vittinghoff E, Applegate W, Varner E, Snyder T. Postmenopausal hormones and incontinence: the Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:116–20. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hendrix SL, Cochrane BB, Nygaard IE, et al. Effects of estrogen with and without progestin on urinary incontinence. JAMA. 2005;293:935–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.8.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson S, James M, Abrams P. The effect of oestradiol on vaginal collagen metabolism in postmenopausal women with genuine stress incontinence. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;109:339–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson D, Rainer RO, Washburn SA, Clarkson TB. Effects of estrogen and progestin replacement on the urogenital tract of the ovariectomized cynomolgus monkey. Neurourol Urodyn. 1996;15:215–21. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6777(1996)15:3<215::AID-NAU6>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russo A, Botten R, Kong MF, et al. Effects of acute hyperglycaemia on anorectal motor and sensory function in diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2004;21:176–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soffer EE, Hull T. Fecal incontinence: a practical approach to evaluation and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1873–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rockwood TH, Church JM, Fleshman JW, et al. Fecal Incontinence Quality of Life Scale: quality of life instrument for patients with fecal incontinence. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02237236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]