Abstract

Integration of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) into the host genome is catalyzed by the viral integrase (IN) and preferentially occurs within transcriptionally active genes. During the early phase of HIV-1 infection, the incoming viral preintegration complex (PIC) recruits the integrase interactor 1 (INI1)/hSNF5, a chromatin remodeling factor which directly binds to HIV-1 IN. The impact of this event on viral replication is so far unknown, although it has been hypothesized that it could tether the preintegration complex to transcriptionally active genes, thus contributing to the bias of HIV integration for these regions of the genome. Here, we demonstrate that while INI1 is dispensable for HIV-1 transduction, it can facilitate HIV-1 transcription by enhancing Tat function. INI1 bound to Tat and both the repeat (Rpt) 1 and Rpt 2 domains of INI1 were required for efficient activation of Tat-mediated transcription. These results suggest that the incoming PICs might recruit INI1 to facilitate proviral transcription.

Finding

Integrase (IN) catalyses the integration of viral DNA into the host genome, which is an essential step of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) replication [1]. Integrase interactor 1 (INI1), also known as hSNF5, a core component of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling SWI/SNF complex [2], directly interacts with HIV-1 IN and stimulates its activity in vitro [3]. INI1 contains three conserved regions including two direct imperfect repeats, repeat Rpt 1 and Rpt2, and a carboxyl (C)-terminal coiled-coil domain [4]. INI1 also acts as a tumor suppressor, as mutations in the ini1 gene leads to aggressive pediatric atypical teratoid and malignant rhabdoid tumors (AT/MRTs) [5], suggesting a role for the SWI/SNF complex in control of the cell cycle. In fact, INI1 induces cell cycle arrest at G1 through repression of cyclin D1 transcription [6,7].

INI1 has been reported to interact with other viral proteins, including the Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2) [8-10], human papillomavirus E1 [11], and herpesvirus K8 [12] as well as cellular factors c-MYC [13], ALL1 (MLL) [14], GADD34 [15], and p53 [16]. During the early phase of the HIV-1 life cycle, the incoming HIV-1 preintegration complex (PIC) triggers the exportin-mediated cytoplasmic export of and associates with INI1 and PML [17,18]. The PML-nuclear body (PML-NB)/nuclear domain 10 (ND10)/PML oncogenic domain (POD) is a target of DNA viruses such as herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1), human cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus, papillomavirus, and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [19]. The recruitment of PML to HIV-1 PICs could promote its association with PML-interacting proteins such as the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) CBP/p300, or with other transcription factors. Similarly, the binding of INI1 to the HIV-1 PICs may trigger the recruitment of the SWI/SNF complex to the PIC, possibly targeting HIV integration to actively transcribed regions of the genome or facilitating subsequent expression of the provirus. To probe these issues, we investigated the potential roles of INI1 and PML in HIV-1 integration and transcription.

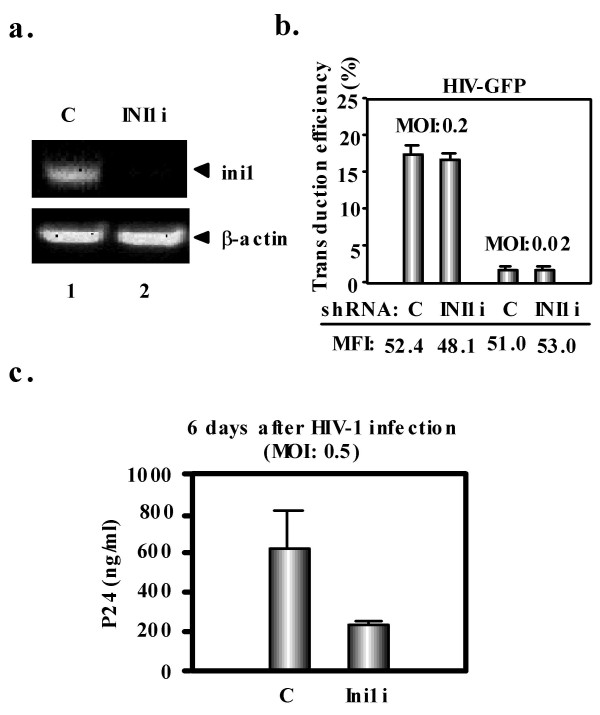

To analyze the effect of INI1 on HIV-1 transduction efficiency, we first used lentiviral vector-mediated RNA interference to stably knockdown INI1 protein in CD4+ LTR-β-Gal HeLa-derived P4.2 cells [20]. Oligonucleotides with the following sense and antisense sequences were used for the cloning of small hairpin RNA (shRNA)-encoding sequences in lentiviral vector: INI1, 5'-GATCCCCAGGCAACAGGTCATGTTCATTCAAGAGATGAACATGACCTGTTGCCTTTTTTGGAAA-3' (sense), 5'-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAAGGCAACAGGTCATGTTCATCTCTTGAATGAACATGACCTGTTGCCTGGG-3' (antisense). The oligonucleotides above were annealed and subcloned into the BglII-HindIII site of pSUPER [21]. To construct pLVshRNA against INI1 (pLV281), the BamHI-SalI fragment of pSUPER-INI1i (pSP281) plasmid was subcloned into the BamHI-SalI site of pRDI292 [22], downstream from an RNA polymerase III promoter within the context of an HIV-1-derived self-inactivating lentiviral vector containing a puromycin marker allowing for the selection of the transduced cells. We used the vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV)-G pseudotyped HIV1 based vector system as previously described [23,24]. RT-PCR measurements demonstrated a very effective downregulation of ini1 mRNA in cells transduced with the lentiviral vector expressing the INI1 shRNA (Fig. 1a). These and control P4.2 cells were then exposed to a VSV-G-pseudotyped, HIV-1-derived lentiviral vector expressing GFP under the control of the E1Fα promoter. FACS analyses performed forty-eight hours later revealed that the INI1 knockdown (INI1i) and control P4.2 cells (C) were equally susceptible to lentiviral vector-mediated transduction (Fig. 1b). As well, an HIV vector could effectively transduce INI1-deficient MON cells derived from a malignant rhabdoid tumor (data not shown), suggesting that INI1 is not essential for HIV-1 integration. We then measured rates of HIV-1 replication in the INI1 knockdown P4.2 cells. After infection with an HIV-1 X4 strain, p24 viral capsid levels were significantly reduced in the supernatant of INI1 knockdown cells compared with control P4.2 cells (Fig. 1c). In view of the normal transduction susceptibility of these cells, this results suggested a role for INI1 in later step of replication.

Figure 1.

INI1 is dispensable for HIV-1 transduction. a. Inhibition of ini1 expression by shRNA-producing lentiviral vector. Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel analysis of RT-PCR amplification products of cytoplasmic RNA from INI1 knockdown P4.2 cells (INI1i) as well as in P4.2 cells transduced with a control (C) lentiviral vector. Cytoplasmic RNA was obtained using RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and RT-PCR was performed using SuperScript one-step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq kit (Invitrogen) with following primers: ini1, 5'-TCTGGAGGCGACTAGCCACTGTG-3' (forward primer) and 5'-GATCACAGCTGGGTCATGGTCATC-3' (reverse primer); beta-actin, 5'-TGACGGGGTCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTA-3' (forward primer) and 5'-CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGACGATGGAGGC-3' (reverse primer). b. Transduction efficiency in the same cells was determined by GFP fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis with a FACStrak apparatus (Becton Dickinson) 2 days after exposure to VSV-G-pseudotyped GFP-expressing HIV-1-derived lentiviral vector at the indicated MOI. Experiments were done in duplicate and columns represent the mean percentage of transduced cells, with mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) indicated below. c. Reduced HIV-1 replication in INI1 knockdown cells. INI1 knockdown P4.2 cells were infected with HIV-1 at a MOI of 0.5. HIV-1 replication was assayed by p24 ELISA in the culture supernatant 6 days later.

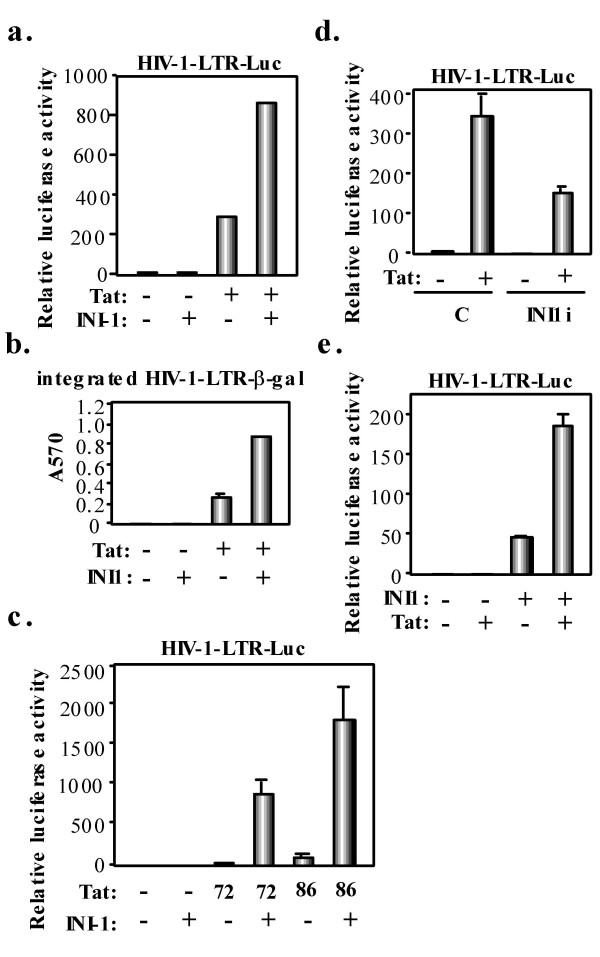

To test the possibility that INI1 might modulate HIV-1 transcription, CD4+ HeLa P4.2 cells were cotransfected with plasmids expressing Tat and/or INI1, together with a Tat-responsive HIV-1-LTR-driven luciferase reporter plasmid [25]. INI1 significantly increased Tat-mediated trans-activation of the HIV-1 LTR (about 4 fold), while it had a negligible effect in the absence of transactivator (Fig. 2a). As well, INI1 could coactivate the Tat-mediated transcription of a stably integrated HIV1-LTR-β-gal construct, as assessed by measuring LacZ activity in the transfected P4.2 cells (Fig. 2b). To identify the domain of Tat essential for response to INI1, we used the C-terminal deletion mutants of Tat, Tat72 and Tat86 [26]. INI1 could fully coactivate their transcriptional activities (Fig. 2c), indicating that the C-terminal domain of Tat (amino acids 73–101) is dispensable for transcriptional activation by INI1. Next, we found that Tat-mediated transcription was significantly inhibited in INI1 knockdown P4.2 cells compared to control, INI1-expressing P4.2 cells (Fig. 2d). Reciprocally, Tat activity was markedly increased in INI1 deficient MON cells when INI1 was reintroduced by transfection (Fig. 2e). Taken together, these data demonstrate that INI1 synergizes with Tat to activate HIV-1 transcription.

Figure 2.

INI1 coactivates Tat-mediated HIV-1 transcription. a. P4.2 cells (2 × 104 cells per well) were cotransfected with 100 ng of pHIV-1-LTR-Luc [25], 100 ng of pcDNA3-Tat101-FLAG [41], and/or 200 ng of pCGN-INI1 [7]. Luciferase assay was performed 24 h later. All transfections utilized equal total amounts of plasmid DNA owing to the addition of empty vector into the transfection mixture. Results were obtained through three independent transfections. Relative stimulation of luciferase activity (fold) is shown. b. 100 ng of pcDNA3-Tat101-FLAG, and/or 200 ng of pCGN-INI1 were cotransfected into P4.2 cells in triplicate. Beta-galactosidase activity was measured 24 h later. c. P4.2 cells were cotransfected with 100 ng of pHIV-1-LTR-Luc, 50 ng of pH2F Tat (Tat86) or pH2Tat (Tat72) [26], and/or 200 ng of pCGN-INI1 and performed luciferase assays 24 h later. d. 100 ng of pHIV-1-LTR-Luc, and/or 100 ng of pcDNA3-Tat101-FLAG were cotransfected into INI1 knockdown P4.2 cells (INI1i) or P4.2 cells transduced with a control (C) lentiviral vector and luciferase assays were performed 24 h later. e. INI1 deficient MON cells (2 × 104 cells per well) were cotransfected with 100 ng of pHIV-1-LTR-Luc, 50 ng of pcDNA3-Tat101-FLAG, and/or 200 ng of pCGN-INI1 and luciferase assays performed 24 h later.

To probe the mechanism of this phenomenon, we performed co-immunoprecipitation analyses on extracts of 293T cells expressing FLAG-tagged Tat- and HA-tagged INI1 (Fig. 3). Both proteins could be immunoprecipitated with either anti-Flag or anti-HA antibody, indicating that they formed a complex, whether directly or indirectly.

Figure 3.

INI1 binds to Tat. 293T cells were cotransfected with 5 μg of pcDNA3-Tat101-FLAG [41] and/or 5 μg of pCGN-HA-INI1 [7]. Cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 4 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP-40, 10 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM DTT and 1 mM PMSF. Lysates were pre-cleared with 30 μl of protein-G-sepharose (Amersham Biosciences). Pre-cleared supernatants were incubated with either 2 μg of anti-HA antibody (HA 11, Babco) or anti-FLAG antibody (M2, Sigma) at 4°C for 1 h. Following absorption of the precipitates on 30 μl of protein-G-sepharose resin for 1 h, the resin was washed four times with 700 μl lysis buffer. Bound proteins were eluted by boiling the resin for 5 min in 1× Laemmli sample buffer. The proteins were then subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblotting analysis using either anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibodies.

To identify the domain of INI1 important for boosting Tat function, we co-expressed Tat and various INI1 deletion mutants [7] in 293T cells transfected with the HIV-1-LTR-luciferase plasmid (Fig. 4a). The full-length protein (INI1) and the two deletion mutants (20.2 and 1.2) still containing repeat Rpt 1 and Rpt2 domains increased Tat-mediated HIV-1 transcription by a factor ten (Fig. 4b). In contrast, mutants 3B and 27B, which lack the Rpt2 domain, could still bind Tat (Fig. 4c), but enhanced transcription by only 2-fold. These results suggest that both Rpt1 and Rpt2 domains of INI1 participate in allowing for full coactivation of Tat-mediated HIV-1 transcription. Interestingly, both Rpt1 and Rpt2 domain are required for the formation of a functional SWI/SNF complex.

Figure 4.

Both Rpt1 and Rpt2 domains of INI1 are required for the efficient activation of Tat-mediated HIV-1 transcription. a. Schematic representation of HA-tagged full-length INI1 and its mutants. b. 293T cells (2 × 104 cells per well) were cotransfected with 100 ng of pHIV-1-LTR-Luc [25], 50 ng of pcDNA3-Tat101-FLAG [41], and/or 200 ng of pCGN-INI1 or its mutant (20.2, 1.2, 3B, 27B) [7] in triplicate and luciferase assays were performed 24 h later. c. 293T cells were cotransfected with 5 μg of pcDNA3-Tat101-FLAG and/or 5 μg of pCGN-HA-INI1 or its mutant (20.2, 3B, 27B) and IP-western blotting was performed in the similar way as shown in Fig. 3. Asterisk denotes HA-INI1 or its mutant.

Tat-mediated transactivation is essential for HIV-1 replication. Tat exerts its transcriptional effect by binding of P-TEFb, a transcription elongation factor composed of cyclin T1 and CDK9, and the interaction of Tat with P-TEFb and TAR leads to hyperphosphorylation of the C-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) thus increasing the processivity of RNA Pol II [27]. In addition, it has been suggested that Tat plays a critical role in the assembly of the transcription complex (TC) during preinitiation [27]. It is likely that the interaction of Tat with the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex promotes this step rather than the elongation of viral transcripts. Correspondingly, our data are consistent with recent reports indicating that SWI/SNF is recruited onto the HIV-1-LTR promoter in Tat-dependent manner [28-30]. These other studies further revealed that, in addition to INI1, Tat also recruits Brm or the closely related Brg-1, the ATPase subunit of the SWI/SNF complex. INI1 and Brg-1 then appear to synergize with the p300 histone acetyltransferase to activate the HIV-1 promoter. Both the binding of Tat to Brm and the synergistic activation of the HIV LTR by Tat and the SWI/SNF complex were found to require Tat acetylation on lysine 50 [28-30].

During the early phase of the HIV-1 life cycle, not only INI1 but also PML is exported to the cytoplasm where it can be found in association with the incoming preintegration complex [17,18]. The recruitment of PML to PICs could subsequently promote the association of PML-interacting proteins such as histone acetyltransferase (HAT) CBP/p300 or other transcription regulators to the HIV promoter. P300 was shown to bind to HIV1 IN and enhances the catalytic activity of this recombinase by acetylation [31]. Interestingly, Marcello et al. found that cyclin T1, the cellular cofactor of Tat responsible for phosphorylating the C-terminus of Pol II polymerase, hence of augmenting the processivity of HIV1 transcription, is recruited to PML nuclear bodies through a direct interaction with the PML protein [32]. Therefore, PML might regulate Tat-mediated transcription through its association with cyclin T1. However, we failed to observe significant effects of PML on Tat-mediated transcription as well as HIV-1 transduction efficiency in HeLa P4.2 cells in which levels of PML were decreased by at least 90% by RNA interference (data not shown). A possible influence of PML on HIV replication thus remains to be demonstrated, perhaps using other cellular systems and more effective knockdowns of this gene.

Retroviral integration favors active genes, MLV concentrating in and around promoters while HIV tends to land in the transcribed region of genes [33-35]. The determinant of such selectivity is unknown. High mobility group protein A1 (HMG-A1), barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF) and Ku have been suggested to influence this step, as these proteins are found in both HIV-1 and MLV PICs [1]. Another candidate is lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF)/p75, which was identified as an IN-interacting protein [36] that can enhance HIV-1 IN strand transfer activity in vitro [36] and influence the intracellular trafficking of HIV-1 but not MLV IN [37]. Accordingly, it was recently demonstrated that LEDGF can affect HIV1 integration site selection in human cells [38]. Whether INI1, which binds to HIV-1 IN but not to MLV IN [39], also participates in this process remains to be established. While this protein is dispensable for HIV-1 transduction per se (Fig. 1 and reference [18]), Maroun et al. recently reported that INI1 interferes with early steps of HIV-1 infection [40]. Moreover, we did not ask whether integration site selection was modified in INI1 knockdown cells. While further studies are required to clarify the roles of factors that associate with the retroviral preintegration complex, the present work suggests that some of them may exert their effect after the provirus is established.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

YA carried out luciferase assay, immunoprecipitation, and was involved in drafting the manuscript. FS and PT carried out luciferase assays, western blotting, and PML knockdown study. AT participated in the construction of lentiviral vector expressing INI1 shRNA. DT participated in the design of the study and in drafting the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Bastien Mangeat, Sandrine Vianin, and Elisabeth Buhlmann for discussion and help with the experiments, and Monsef Benkirane, Masakazu Hatanaka, Hiroyuki Sakai, Yoshihiro Kitamura, Richard Iggo, and Ganjam V. Kalpana for the gift of reagents. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (18790326), and the Naito Foundation.

Contributor Information

Yasuo Ariumi, Email: ariumi@md.okayama-u.ac.jp.

Fatima Serhan, Email: fatima.serhan@epfl.ch.

Priscilla Turelli, Email: priscilla.turelli@epfl.ch.

Amalio Telenti, Email: amalio.telenti@chuv.ch.

Didier Trono, Email: didier.trono@epfl.ch.

References

- Turlure F, Devroe E, Silver PA, Engelman A. Human cell proteins and human immunodeficiency virus DNA integration. Front Biosci. 2004;9:3187–3208. doi: 10.2741/1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Côté J, Xue Y, Zhou S, Khavari PA, Biggar SR, Muchardt C, Kalpana GV, Goff SP, Yaniv M, Workman JL, Crabtree GR. Purification and biochemical heterogeneity of the mammalian SWI-SNF complex. EMBO J. 1996;15:5370–5382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalpana GV, Marmon S, Wang W, Crabtree GR, Goff SP. Binding and stimulation of HIV-1 integrase by a human homolog of yeast transcription factor SNF5. Science. 1994;266:2002–2006. doi: 10.1126/science.7801128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov A, Yung E, Kalpana GV. Structure-function analysis of integrase interactor 1/hSNF5L1 reveals differential properties of two repeat motifs present in the highly conserved region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1120–1125. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versteege I, Sévenet N, Lange J, Rousseau-Merck M-F, Ambros P, Handgretinger R, Aurias A, Delattre O. Truncating mutations of hSNF5/INI1 in aggressive paediatric cancer. Nature. 1998;394:203–206. doi: 10.1038/28212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ae K, Kobayashi N, Sakuma R, Ogata T, Kuroda H, Kawaguchi N, Shinomiya K, Kitamura Y. Chromatin remodeling factor encoded by ini1 induces G1 arrest and apoptosis in ini1-deficient cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:3112–120. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z-K, Davies KP, Allen J, Zhu L, Pestell RG, Zagzag D, Kalpana GV. Cell cycle arrest and repression of cyclin D transcription by INI1/hSNF5. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5975–5988. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.16.5975-5988.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowski B, Chen SYJ, Schubach WH. CKII site in Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 controls binding to hSNF5/Ini1 and is important for growth transformation. J Virol. 2004;78:6067–6072. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.11.6067-6072.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DY, Kalpana GV, Goff SP, Schubach WH. Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2 (EBNA2) binds to a component of the human SNF-SWI complex, hSNF5/Ini1. J Virol. 1996;70:6020–6028. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.6020-6028.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DY, Krumm A, Schubach WH. Promoter-specific targeting of human SWI-SNF complex by Epstein-Barr virus nuclear protein 2. J Virol. 2000;74:8893–8903. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.19.8893-8903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Sohn H, Kalpana GV, Choe J. Interaction of E1 and hSNF5 proteins stimulates replication of human papillomavirus DNA. Nature. 1999;399:487–491. doi: 10.1038/20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S, Lee D, Gwack Y, Min H, Choe J. Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus K8 protein interacts with hSNF5. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:665–676. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18699-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng SW, Davies KP, Yung E, Beltran RJ, Yu J, Kalpana GV. c-MYC interacts with INI1/hSNF5 and requires the SWI/SNF complex for transactivation function. Nat Genet. 1999;22:102–105. doi: 10.1038/8811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt-Rosen O, Rozovskaia T, Burakov D, Sedkov Y, Tillib S, Blechman J, Nakamura T, Croce CM, Mazo A, Canaani E. The C-terminal SET domains of ALL-1 and TRITHORAX interact with the INI1 and SNR1 proteins, components of the SWI/SNF complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4152–4157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler HT, Chinery R, Wu DY, Kussick SJ, Payne JM, Fornace AJ, Jr, Tkachuk DC. Leukemic HRX fusion proteins inhibit GADD34-induced apoptosis and associate with the GADD34 and hSNF5/INI1 proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7050–7060. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.7050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee D, Kim JW, Seo T, Hwang SG, Choi E-J, Choe J. SWI/SNF complex interacts tumor suppressor p53 and is necessary for the activation of p53-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:22330–22337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turelli P, Doucas V, Craig E, Mangeat B, Klages N, Evans R, Kalpana G, Trono D. Cytoplasmic recruitment of INI1 and PML on incoming HIV preintegration complexes: interference with early steps of viral replication. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1245–1254. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00255-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boese A, Sommer P, Gaussin A, Reimann A, Nehrbass U. Ini1/hSNF5 is dispensable for retrovirus-induced cytoplasmic accumulation of PML and does not interfer with integration. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maul GG. Nuclear domain 10, the site of DNA virus transcription and replication. BioEssays. 1998;20:660–667. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<660::AID-BIES9>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charneau P, Mirambeau G, Roux P, Paulous S, Buc H, Clavel F. HIV1 reverse transcription. A termination step at the center of the genome. J Mol Biol. 1994;241:651–662. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brummelkamp TR, Bernard R, Agami R. A system for stable expression of short interfering RNAs in mammalian cells. Science. 2002;296:550–553. doi: 10.1126/science.1068999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge AJ, Pebernard S, Ducraux A, Nicoulaz A-L, Iggo R. Induction of an interferon response by RNAi vectors in mammalian cells. Nat Genet. 2003;34:263–264. doi: 10.1038/ng1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naldini L, Blömer U, Gallay P, Ory D, Mulligan R, Gage FH, Verma IM, Trono D. In vivo gene delivery and stable transduction of nondividing cells by a lentiviral vector. Science. 1996;272:263–267. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5259.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zufferey R, Nagy D, Mandel RJ, Naldini L, Trono D. Multiply attenuated lentiviral vector achieves efficient gene delivery in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:871–875. doi: 10.1038/nbt0997-871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariumi Y, Kaida A, Hatanaka M, Shimotohno K. Functional cross-talk of HIV1 Tat with p53 through its C-terminal domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:556–561. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo S, Kubota S, Siomi H, Adachi A, Oroszlan S, Maki M, Hatanaka M. A region of basic amino-acid cluster in HIV-1 Tat protein is essential for trans-acting activity and nucleolar localization. Virus Genes. 1989;3:99–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00125123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady J, Kashanchi F. Tat gets the "green" light on transcription initiation. Retrovirology. 2005;2:69. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudi T, Parra M, Vries RGJ, Kauder SE, Verrijzer CP, Ott M, Verdin E. The SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex is a cofactor for Tat transactivation of the HIV promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19960–19968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tréand C, du Chéné I, Brés V, Kiernan R, Benarous R, Benkirane M, Emiliani S. Requirement for SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex in Tat-mediated activation of the HIV-1 promoter. EMBO J. 2006;25:1690–1699. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbottah E, Deng L, Dannenberg LO, Pumfery A, Kashanchi F. Effect of SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex on HIV-1 Tat activated transcription. Retrovirology. 2006;3:48. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cereseto A, Manganaro L, Gutierrez MI, Terreni M, Fittipaldi A, Lusic M, Marcello A, Giacca M. Acetylation of HIV-1 integrase by p300 regulates viral integration. EMBO J. 2005;24:3070–3081. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcello A, Ferrari A, Pellegrini V, Pegoraro G, Lusic M, Beltram F, Giacca M. Recruitment of human cyclin T1 to nuclear bodies through direct interaction with the PML protein. EMBO J. 2003;22:2156–2166. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trono D. Picking the right spot. Science. 2003;300:1670–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.1086238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder ARW, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR, Bushman F. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell. 2002;110:521–529. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Li Y, Crise B, Burgess SM. Transcription start regions in the human genome are favored targets for MLV integration. Science. 2003;300:1749–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1083413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherepanov P, Maertens G, Proost P, Devreese B, Van Beeumen J, Engelborghs Y, De Clercq E, Debyser Z. HIV-1 integrase forms stable tetramers and associates with LEDGF/p75 protein in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:372–381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209278200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano M, Vanegas M, Fregoso O, Saenz D, Chung S, Peretz M, Poeschla EM. LEDGF/p75 determines cellular trafficking of diverse lentiviral but not murine oncoretroviral integrase proteins and is a component of functional lentiviral preintegration complexes. J Virol. 2004;78:9524–9537. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.17.9524-9537.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciuffi A, Llano M, Poeschla E, Hoffmann C, Leipzig J, Shinn P, Ecker JR, Bushman F. A role for LEDGF/p75 in targeting HIV DNA integration. Nat Med. 2005;11:1287–1289. doi: 10.1038/nm1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung E, Sorin M, Wang E-J, Perumal S, Ott D, Kalpana GV. Specificity of interaction of INI1/hSNF5 with retroviral integrases and its functional significance. J Virol. 2004;78:2222–2231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2222-2231.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroun M, Delelis O, Coadou G, Bader T, Ségéral E, Mbemba G, Petit C, Sonigo P, Rain J-C, Mouscadet J-F, Benarous R, Emiliani S. Inhibition of early steps of HIV-1 replication by SNF5/Ini1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:22736–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604849200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brés V, Kiernan RE, Linares LK, Chable-Bessia C, Plechakova O, Treand C, Emiliani S, Peloponese JM, Jeang KT, Coux O, Scheffner M, Benkirane M. A non-proteolytic role for ubiquitin in Tat-mediated transactivation of the HIV1 promoter. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:754–761. doi: 10.1038/ncb1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]