Abstract

Observations of fast unfolding events in proteins are typically restricted to <100°C. We use a novel apparatus to heat and cool enzymes within tens of nanoseconds to temperatures well in excess of the boiling point. The nanosecond temperature spikes are too fast to allow water to boil but can affect protein function. Spikes of 174°C for catalase and ∼290°C for horseradish peroxidase are required to produce irreversible loss of enzyme activity. Similar temperature spikes have no effect when restricted to 100°C or below. These results indicate that the “speed limit” for the thermal unfolding of large proteins is shorter than 10−8 s. The unfolding rate at high temperature is consistent with extrapolation of low temperature rates over 12 orders of magnitude using the Arrhenius relation.

Probing the folding and unfolding processes of proteins as a function of temperature is a major challenge in biophysics. Here we examine the effects of temperature spikes that heat and cool proteins within tens of nanoseconds. Our results show these spikes are capable of causing irreversible changes sufficient to eliminate protein activity.

The folding and unfolding of proteins over milliseconds is commonly described using conventional chemical kinetics and transition-state theory (1). On submicrosecond timescales, it has been reported that proteins are simply too large to undergo the significant structural changes required for folding, and that the assumptions of conventional rate kinetics break down (1). “Speed limits” for protein folding of the order of 1 μs have been reported (2,3). In general, smaller and less complex proteins fold and unfold more quickly than larger proteins, and most cases of folding near the “speed limit” involve polypeptides <100 residues in size.

In the case of unfolding, the opportunity exists to substantially increase the rates by increasing the temperature. “T-jump” experiments have observed unfolding of proteins on microsecond timescales (4,5), and significant structural change of small proteins in nanoseconds (6). Molecular dynamics simulations performed at high temperatures (100–225°C) have predicted an unfolding “speed limit” of ∼0.1 ns (7), but so far no experiments have been able to show unfolding near this limit.

Temperature-jump experiments are restricted to temperatures below the boiling point of the solution, thus limiting the rate at which unfolding may occur. Attempts to heat proteins to higher temperatures have been made (8), but these simultaneously induce nonthermal effects (extreme levels of electromagnetic fields and microbubbles) likely to affect proteins. Here, we use a technique that can heat proteins to calibrated temperatures well above 100°C without these potentially destructive effects. Our measurements achieve heat/cool times of 40 ns, with significant cooling within 10 ns.

By measuring protein activity we monitor the active site of proteins without making assumptions about how much secondary structure remains intact away from the active site. In this article, we define unfolding to refer to a structural change significant enough to cause loss of protein activity.

All reports of thermally induced unfolding on a nanosecond timescale have used proteins that unfold reversibly. In this article, nanosecond temperature spikes are applied to two enzymes, horseradish peroxidase isozyme C (HRP-C) and catalase, which have previously been shown to irreversibly unfold when heated (9,10). Temperature spikes below 100°C do not affect these enzymes, but at higher temperatures, irreversible thermal unfolding is induced using temperature spikes lasting only tens of nanoseconds.

We exploit three opportunities for the production of very brief temperature spikes in solution:

Heat rapidly diffuses away from very thin layers in a heat conductive medium. By solving the heat conduction equation, it is readily shown that confining a temperature rise to a small structure results in extremely fast cooling times.

Metals combine a high thermal conductivity with a large extinction coefficient for visible light. For example, a 150 nm gold film on glass transmits <0.1% of incident laser light (Fig. 1 a). The film is also thin enough to deliver significant heat to the gold surface and the liquid medium in contact with it. In this way, “pure” conducted heat is delivered to macromolecules attached to the gold-liquid interface without the complicating effect of large electromagnetic field or photons with sufficient energy to break covalent bonds.

The boiling of a liquid on a surface requires the formation of active vapor nuclei. For a smooth water-metal interface at the temperatures and timescales that we employ, the rate of vapor generation is negligible (11).

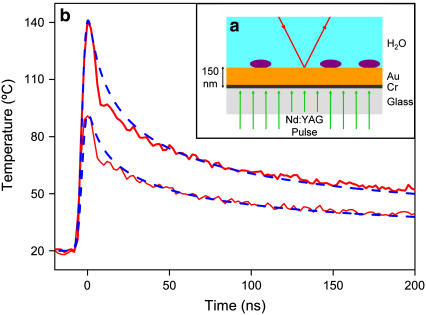

FIGURE 1.

Laser heating system used to deliver temperature pulses to proteins (purple ellipses). Temperature is monitored using the top reflecting beam (red). (b) Two typical temperature pulses comparing the calculated transient (dashed blue lines) and the measured temperature (red lines). Full width at half-maximum of both modeled spikes is 40 ns.

Our apparatus (Fig. 1 a) consists of a frequency doubled (532 nm) Nd:YAG laser with 5 ns pulse length, heating a 135 nm thick gold film with 15 nm chromium underlayer on a glass substrate. The chromium is used to increase film adhesion and also increases the absorbance of laser light.

Thermal modeling, previously reported in detail (12), shows that temperature rises affect an aqueous layer up to 30 nm from the gold surface (much larger than the protein dimensions). The modeled temperature profiles are in close agreement with temperature measurements obtained using a thermoreflectance method. There is a significant reduction in temperature elevation within 10 ns and a 50% reduction in 40 ns (Fig. 1 b). The uniformity of surface temperature is determined by the intensity distribution of the laser beam, by the uniformity of the gold layer, and by the effect of interference fringes from the glass substrate. The total nonuniformity in temperature rise, expressed as a standard deviation of the mean temperature change, was 18 ± 4% for experiments with catalase and 25 ± 5% for HRP-C.

Catalase is a ubiquitous enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of hydrogen peroxide and whose activity can be simply measured (13). It is a 250 kDa tetramer, considerably larger than the proteins whose nanosecond unfolding kinetics have previously been observed (4–6).

HRP-C is a 43 kDa enzyme widely used in biotechnology for its ability to oxidize a variety of substances in a reaction coupled with hydrogen peroxide. We found that both proteins were enzymatically active when adsorbed onto gold films and suffered irreversible loss of activity after ambient heating. Binding of the proteins to the gold surface reduced protein stability, with the thermal inactivation rate of catalase on the surface roughly equivalent to that in a solution 10°C warmer than the surface.

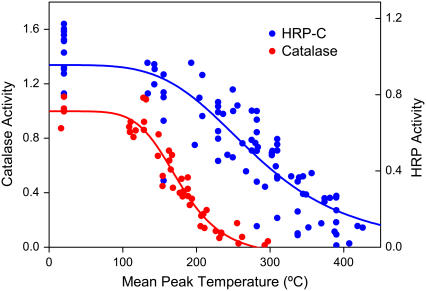

The enzymatic activities of catalase and HRP after exposure to thermal spikes of varying peak temperatures are shown in Fig. 2. The temperature range over which the loss of function occurs is broadened due to nonuniformities in the exposure. A 50% loss of activity was used as the criterion for assessing the loss of function as this measure was found to be insensitive to these nonuniformities. For catalase, 50% loss of activity occurred after a single temperature pulse reaching 174 ± 7°C (95% confidence interval), or after 100 pulses each reaching 139 ± 9°C (95% confidence interval). Fig. 2 also presents data for HRP-C, which show a similar pattern of activity loss, but require significantly greater temperatures. Loss of activity for HRP-C was achieved using 100 pulses each producing a temperature of ∼290°C. Fourier transform infrared measurements of the protein amide I band before and after heating show that the loss of activity is not due to removal of protein from the surface.

FIGURE 2.

Normalized enzymatic activities for catalase (red) and HRP-C (blue). Data above 230°C assume a linear extrapolation of the measured temperature versus pulse energy relation beyond that point.

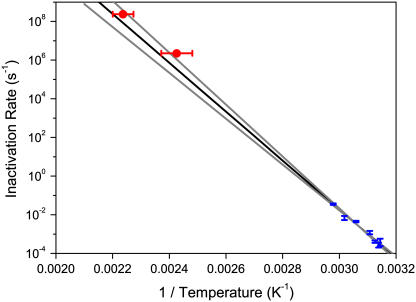

To elucidate the mechanism involved in catalase inactivation, we have compared the laser heating of catalase with experiments performed using ambient heating between 45°C and 63°C for catalase attached to identical chromium-gold films. The inactivation rates observed in this range were fit with a simple Arrhenius equation, which when extrapolated to higher temperatures predicts inactivation rates in good agreement with those measured using the laser apparatus (Fig. 3). The intermediate range of Fig. 3 (k ∼ 100 – 104 s−1) cannot be measured with either technique used here. This range would require a prohibitively large number of laser pulses using the thermal spike technique. Nonetheless, the compatibility of the two results, using water bath heating and laser-induced temperature spikes, is strongly suggestive of a similar mechanism for thermally induced unfolding across a change in inactivation rate of nearly 12 orders of magnitude.

FIGURE 3.

Arrhenius plot of the rate of loss of enzymatic activity of catalase immobilized at a gold surface (see Fig. 1 a). The data points in the lower right are obtained by heating in a water bath (error bars represent mean ± SE fits to inactivation rate), whereas the upper left data points used the laser heating apparatus 1 (error bars are 95% confidence interval). The line of best fit (bold) and 95% confidence interval lines were determined by fitting the water bath data only.

There are strong theoretical reasons to expect that the Arrhenius behavior we observe will not continue indefinitely. Protein unfolding is likely to be subject to a “speed limit”. The limit suggested by molecular dynamics modeling, performed on substantially smaller proteins than those used here, is of the order of 1010 s−1 (7). We have shown that behavior similar to that predicted by an Arrhenius equation holds very close to this predicted limit, for two large proteins (43 and 250 kDa). We have also demonstrated experimentally that irreversible unfolding of these proteins can occur due to thermal spikes lasting only tens of nanoseconds in duration, a timescale significantly faster than the “speed limit” associated with protein folding.

The ability to probe protein kinetics at ultrahigh temperatures on a nanosecond timescale has direct applications to the management of pulsed exposures to electromagnetic radiation (14), and to the development of new techniques emerging in laser surgery and medicine (15,16). Our use of a planar geometry, besides allowing a straightforward measurement of temperature, has the advantage of enabling surface imaging after nanosecond temperature spikes. This would provide opportunities to investigate the kinetic behavior of biological macromolecules such as motor proteins (17). Moreover, our results provide information about fundamental protein kinetics at temperatures previously inaccessible to experiment.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

References

- 1.Yang, W. Y., and M. Gruebele. 2003. Folding at the speed limit. Nature. 423:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qiu, L. L., and S. J. Hagen. 2005. Internal friction in the ultrafast folding of the tryptophan cage. Chem. Phys. 312:327–333. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li, M. S., D. K. Klimov, and D. Thirumalai. 2004. Thermal denaturation and folding rates of single domain proteins: size matters. Polym. 45:573–579. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung, H. S., M. Khalil, A. W. Smith, Z. Ganim, and A. Tokmakoff. 2005. Conformational changes during the nanosecond-to-millisecond unfolding of ubiquitin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:612–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayor, U., N. R. Guydosh, C. M. Johnson, J. G. Grossmann, S. Sato, G. S. Jas, S. M. V. Freund, D. O. V. Alonso, V. Daggett, and A. R. Fersht. 2003. The complete folding pathway of a protein from nanoseconds to microseconds. Nature. 421:863–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips, C. M., Y. Mizutani, and R. M. Hochstrasser. 1995. Ultrafast thermally-induced unfolding of RNase-A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:7292–7296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Day, R., and V. Daggett. 2005. Sensitivity of the folding/unfolding transition state ensemble of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2 to changes in temperature and solvent. Protein Sci. 14:1242–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huttmann, G., B. Radt, J. Serbin, and R. Birngruber. 2003. Inactivation of proteins by irradiation of gold nanoparticles with nano- and picosecond laser pulses. Proc. SPIE. 5142:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartoszek, M., and M. Ksciuczyk. 2005. Study of the temperature influence on catalase using spin labelling method. J. Mol. Struct. 744:733–736. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pina, D. G., A. V. Shnyrova, F. Gavilanes, A. Rodriguez, F. Leal, M. G. Roig, I. Y. Sakharov, G. G. Zhadan, E. Villar, and V. L. Shnyrov. 2001. Thermally induced conformational changes in horseradish peroxidase. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernardin, J. D., and I. Mudawar. 2002. A cavity activation and bubble growth model of the Leidenfrost point. J. Heat Trans.-T. ASME. 124:864–874. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steel, B., M. M. Bilek, C. G. dos Remedios, and D. R. McKenzie. 2004. Apparatus for exposing cell membranes to rapid temperature transients. Eur. Biophys. J. 33:117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen, G., M. Kim, and V. Ogwu. 1996. A modified catalase assay suitable for a plate reader and for the analysis of brain cell cultures. J. Neurosci. Methods. 67:53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurence, J. A., D. R. McKenzie, and K. R. Foster. 2003. Application of the heat equation to the calculation of temperature rises from pulsed microwave exposure. J. Theor. Biol. 222:403–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zharov, V. P., E. N. Galitovskaya, C. Johnson, and T. Kelly. 2005. Synergistic enhancement of selective nanophotothermolysis with gold nanoclusters: potential for cancer therapy. Lasers Surg. Med. 37:219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamad-Schifferli, K., J. J. Schwartz, A. T. Santos, S. Zhang, and J. M. Jacobsen. 2002. Remote electronic control of DNA hybridization through inductive coupling to an attached metal nanocrystal antenna. Nature. 415:152–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawaguchi, K., and S. Ishiwata. 2001. Thermal activation of single kinesin molecules with temperature pulse microscopy. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 49:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]