Abstract

Extraintestinal Escherichia coli strains cause meningitis, sepsis, urinary tract infection, and other infections outside the bowel. We examined here extraintestinal E. coli strain CFT073 by differential fluorescence induction. Pools of CFT073 clones carrying a CFT073 genomic fragment library in a promoterless gfp vector were inoculated intraperitoneally into mice; bacteria were recovered by lavage 6 h later and then subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Eleven promoters were found to be active in the mouse but not in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth culture. Three are linked to genes for enterobactin, aerobactin, and yersiniabactin. Three others are linked to the metabolic genes metA, gltB, and sucA, and another was linked to iha, a possible adhesin. Three lie before open reading frames of unknown function. One promoter is associated with degS, an inner membrane protease. Mutants of the in vivo-induced loci were tested in competition with the wild type in mouse peritonitis. Of the mutants tested, only CFT073 degS was found to be attenuated in peritoneal and in urinary tract infection, with virulence restored by complementation. CFT073 degS shows growth similar to that of the wild type at 37°C but is impaired at 43°C or in 3% ethanol LB broth at 37°C. Compared to the wild type, the mutant shows similar serum survival, motility, hemolysis, erythrocyte agglutination, and tolerance to oxidative stress. It also has the same lipopolysaccharide appearance on a silver-stained gel. The basis for the virulence attenuation is unclear, but because DegS is needed for σE activity, our findings implicate σE and its regulon in E. coli extraintestinal pathogenesis.

Extraintestinal Escherichia coli strains cause meningitis, sepsis, and infections of the urinary tract. These strains are the primary cause of the latter, being responsible for 80% of community-acquired cases, and cause an estimated 30% of all cases of neonatal meningitis (52). The toll of these infections is high: one in five neonates with meningitis dies despite treatment, and urinary tract infection leads to 7.3 million physician office visits and $1.6 billion in medical costs annually (23).

Extraintestinal E. coli differ from fecal strains phenotypically, an observation first made more than 80 years ago when Lyon reported that E. coli strains isolated from urine were more often hemolytic (34). More recently, a study found 58% of pyelonephritis isolates carried hemolysin versus 9% of fecal E. coli from healthy women (40). Disparities are also seen for toxins such as cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1, the siderophore aerobactin, and adhesins such as P pili (20).

Recently, the genomic sequence of the uropathogenic E. coli strain CFT073 was reported (53). A three-way comparison of its genome with those of the laboratory strain MG1655 and the enterohemorrhagic strain EDL933 found that, although all three are E. coli, they have in common only 39% of their combined (i.e., nonredundant) set of proteins. Examination of the large pathogenicity island in CFT073 shows marked differences between it and islands described in two other uropathogenic strains, J96 and 536. The hypothesis was made that these and perhaps other extraintestinal E. coli strains arose independently from multiple clonal lineages (53).

The differences among E. coli strains indicate that there exist forces that drive not only the evolutionary divergence of strains in different niches (laboratory, bowel, urinary tract) but also drive the convergence of disparate lineages within the same niche. Certainly, the physical conditions of the environment, as well as the nature and extent of the host immune response, rank as some of the most potent of these forces, for these would be quite different in different regions of the host.

Recent technical advances have made it possible to observe aspects of pathogen physiology during infection of a host. One such technique is differential fluorescence induction (DFI), which gives a view of a bacterium's genetic response to its environment. Central to DFI is the segregation of bacterial populations by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (50). The fluorescence comes from the Aquorea victorea-derived green fluorescent protein fused to a promoter library constructed from the bacterial genome. Bacteria that carry an active promoter-gfp fusion are separated from clones that do not. Successive sorts from different environments yield bacteria that are fluorescent in vivo but not in vitro, and the differentially induced promoters can be identified by DNA sequence analysis.

DFI was initially used to identify Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium promoters activated by acid stress in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth culture (50). Subsequently, Valdivia and Falkow expanded the technique to identify serovar Typhimurium promoters induced during invasion of macrophages (51). Other groups have studied other bacteria in other broth and tissue culture models (4-6, 28, 37, 43, 45). Recently, Marra et al. described the first use of DFI to identify promoters induced during an animal infection (36). They sorted Streptococcus pneumoniae clones from infections of the middle ear, mouse lung, and peritoneum. The latter involved recovery of S. pneumoniae clones from intraperitoneal chamber implants.

In the present study we sought to sort E. coli directly from lavage fluid from a mouse with peritonitis. This is an in situ use of DFI that marks the first time this technique been applied to the study of an Enterobacteriaceae strain during host infection. Background fluorescence and sorting inefficiencies revealed that FACS of bacteria directly from inflammatory tissue carries technical limitations. Nonetheless, 11 sequences were identified which promote green fluorescent protein expression inside the mouse but not in LB broth culture. Disruption mutations of the associated genes were made, and the mutants were tested in mice in competition with the wild type. Mutation of one gene in particular, degS, caused virulence attenuation both within the mouse peritoneum and in the urinary tract. DegS is required for the activity of the alternative, extracytoplasmic sigma factor σE; thus, the findings here may be the first indication that σE is required for virulence in E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, growth conditions, and reagents.

Uropathogenic E. coli strain CFT073, serotype O6:H1:K2, was isolated from the blood of a woman with acute pyelonephritis (35, 42). Except as noted, bacteria were grown at 37°C in LB broth with shaking or on LB agar. As appropriate, 50 μg of nalidixic acid, 50 μg of kanamycin, or 250 μg of carbenicillin/ml was added. These and other reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo., and recombinant enzymes were from Promega Corp., Madison, Wis. (T4 ligase and Taq polymerase); Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Ind. (Pwo polymerase); and New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass. (restriction enzymes).

Construction of promoter library.

Chromosomal DNA from CFT073 was partially digested with Sau3A, and fragments of from 0.5 to 4 kb were purified after excision from an agarose gel. The fragments were ligated into the BamHI site of pFPV25 immediately before the promoterless gfpmut3 (50). Ligation products were electroporated into CFT073, and eight pools, each containing ca. 2,000 transformants, were assembled and stored at −80°C in LB medium-glycerol.

Mouse peritoneal infection.

Individual bacterial strains or pooled transformants were grown overnight, washed, and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to an inoculum of ca. 5 × 107 CFU in 200 μl. This was injected into the peritoneal cavity of Swiss-Webster female mice (Harlan Teklad, Madison, Wis.). After 6 h, mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation. Dissection was performed to reveal the intact ventral peritoneal wall, and lavage with 2 ml of PBS was carried out. Recovered lavage fluid was cultured on LB agar or directly and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry or sorted by FACS. Spleens from mice were collected by dissection and excision and then were homogenized in 1 ml of PBS. Dilutions of the homogenate were cultured.

DFI.

Aliquots of each pool of CFT073/pFPV25 genomic library transformants were used to start a culture in LB broth. After overnight growth, the bacteria were washed and diluted in PBS then inoculated transperitoneally into mice. The bacteria were recovered by lavage 6 h later and immediately sorted, with nonfluorescent and constitutively fluorescent CFT073/pFPV25 clones used as controls (5). The most fluorescent (uppermost 1%) were collected and grown on plates. The following day, the colonies on LB agar were scraped to pool them and then sorted by FACS. The least fluorescent (lowest 5%) were collected. After overnight growth, the clones were again inoculated into mice, recovered by peritoneal lavage after 6 h, and sorted for high fluorescence, collecting and culturing the uppermost 1%. Individual colonies were subcultured, and then each was individually tested in mice and LB broth to confirm high and low fluorescence, respectively, by flow cytometry.

Sequence analysis.

Plasmid inserts were sequenced (ACGT, Inc., Northbrook, Ill.), and the sequences were aligned to the genome of CFT073 at http://www.genome.wisc.edu/. BLAST searches for sequence homology were carried out at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Generation of mutants.

Deletion mutants of in vivo-induced loci were generated by the linear recombination (λ Red) method of Datsenko and Wanner (17). More than 90% of the putative coding sequence of each locus was deleted, leaving behind the 5′ and 3′ ends. A kanamycin resistance cassette was inserted in place of the deleted sequence, and kanamycin was used for selection. The insertion cassette was derived from the nonpolar (in frame, with added ribosome binding site) plasmid template pKD4 (17). The deletion and insertion mutations were confirmed by PCR.

A disruption mutation of degS was constructed by homologous recombination. A 500-base internal degS fragment was generated by PCR with genomic DNA from strain CFT073 as a template. The fragment extends from bases 248 to 748 (NCBI accession no. AE016767, bases 175543 to 176043) of the predicted 1,063-base degS open reading frame (ORF). KpnI and SacI restriction sites were incorporated into the primers and, after digestion with these enzymes, the 500-bp fragment was ligated into the multiple cloning site of pEP185.2, a conjugative, π-dependent suicide vector (5). This construct, pWAM2851, was placed into the E. coli donor strain S17λpir, and mating introduced pWAM2851 into CFT073. Antibiotic selection (nalidixic acid and chloramphenicol) isolated WAM2853, produced by crossover of pWAM2851 into the degS chromosomal locus. WAM2854 is WAM2853 transformed with a plasmid carrying degS. This plasmid was constructed by insertion of full-length degS between BamHI and PstI sites on pACYC177. For this cloning, the degS insert was generated by PCR from wild-type CFT073 chromosomal DNA (AE016767, bases 175208 to 176372) by using primers incorporating BamHI and PstI restriction sites.

In vitro phenotype screening.

Colony size and morphology were compared on LB agar and MacConkey agar. Guinea pig and human erythrocyte agglutination was used to assess type 1 and P fimbriation, respectively (39). Mannose resistance was checked by the addition of 25 mM mannose to red blood cells agglutinated by bacteria. Hemolysin activity was determined by comparison of colony lysis zones on sheep erythrocyte agar and by liquid hemolysis assay (7). Culture stabs into 0.3% LB agar were used to compare motility. Growth curves were determined by serial optical density at 600 nm readings from LB broth cultures at 37, 43, and at 37°C in LB broth containing 3% (vol/vol) ethanol. Matching readings of the optical density at 600 nm were confirmed by quantitative cultures. Tolerance to oxidative stress was determined by monitoring growth at 37°C in LB broth containing 750 μM H2O2. Tolerance to envelope stress was also examined by monitoring of growth in the presence of 1.5 U of polymyxin B/ml. Serum resistance was assayed by quantitative recovery of bacteria incubated in Veronal-buffered saline plus 50% nonimmune human serum for 1 h at 37°C (32). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) profiles were obtained by whole-cell lysis, followed by proteinase K digestion and then separation by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and silver staining (27).

Competitive murine urinary tract infection.

CBA/J female mice (Harlan Teklad, Madison, Wis.), 6 to 8 weeks old, were anesthetized and inoculated transurethrally by using a catheter and syringe. The inoculum was prepared from LB broth cultures, grown without shaking at 37°C over 6 days, with passaging into fresh broth on the second and fourth days. After centrifugation and resuspension in PBS, type 1 fimbriation was assessed by guinea pig red blood cell agglutination and, if equal, the two strains to be compared (wild-type CFT073 and mutant) were mixed 1:1 to create the inoculum for a total of ca. 5 × 108 bacteria suspended in 50 μl of PBS. Two days after inoculation, mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation, and kidneys and bladder were retrieved by dissection. These tissues were homogenized with PBS inside sterile plastic field specimen bags (Whirl-Pak; Nasco, Fort Atkinson, Wis.) by rolling compression by using a round glass bottle. Homogenates were diluted and cultured on LB agar, and the mutant and wild type were distinguished by antibiotic sensitivity (patching or replica plating onto kanamycin- or chloramphenicol-treated LB agar).

Statistical analysis.

Analysis of relative recovery of strains from competitive mouse infections was done by Mann-Whitney U testing by using the Instat statistical program (GraphPad Software).

RESULTS

DFI analysis.

We sought to identify promoters induced by exposure to conditions inside the mouse peritoneum but repressed by growth in rich medium. A DFI enrichment strategy was used, as described above. From a promoter trap library of ca. 16,000 clones, 11 promoters were found after screening and sequencing steps, to be unique (Table 1). The ratio of in vivo to in vitro fluorescence ranged from 2.9 to 24. All 11 clones matched sequence in CFT073, but three matched putative promoter regions for ORFs of uncertain function. The eight remaining were linked to genes encoding a diverse range of proteins involved in siderophore synthesis, metabolism, regulation, and adherence.

TABLE 1.

E. coli CFT073 clones with differentially induced GFP expression

| Clone | GenBank accession no.a | Insert match (base range) | Inductionb | Putative induced locus | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 301 | AE016767 | 174120-176043 | 2.9 | degS | σE regulation |

| 504 | AE016757 | 183205-183893 | 5.3 | sucA | Succinate dehydrogenase |

| 508 | AE016757 | 73190-74849 | 4.6 | ybdL | Unknown |

| 514 | AE016767 | 26654-27564 | 7.9 | yqjH | Unknown |

| 606 | AE016761 | 115753-114223 | 4.4 | ydiJ | Unknown |

| 723 | AE016762 | 115531-118130 | 9.6 | irp2 | Yersiniabactin synthesis |

| 957 | AE016767 | 156345-157876 | 6.4 | gltB | Glutamate synthesis |

| 1031 | AE016766 | 143717-140819 | 19 | iucA | Aerobactin synthesis |

| 1053 | AE016766 | 124661-123556 | 18 | iha | Adherence (?) |

| 1217 | AE016757 | 63076-66096 | 23 | entC | Enterobactin synthesis |

| 1218 | AE016770 | 210782-211820 | 24 | metA | Methionine synthesis |

NCBI GenBank accession number (sections of CFT073 genome).

Ratio of fluorescence (geometric mean) in peritoneal versus LB broth preparations. The average (mean) of three determinations is given.

Iron acquisition.

Of the 11 promoters, 3 appear to be linked to iron acquisition genes. The siderophore enterobactin is represented on clone 1217, which contains on its insert the promoter of entC, encoding the first enzyme in enterobactin synthesis (49). Another clone, 1031, contains the start of the aerobactin synthesis operon, iucABCD, while a third clone, 723, contains the promoter for irp2, the first gene of the operon for yersiniabactin synthesis (19, 24).

Two other clones show sequences that may be associated with iron acquisition. One, 514, carries the first 42 bases of yqjH, an ORF of unknown function but whose predicted protein product has 28% identity to ViuB, a cytoplasmic vibriobactin utilization protein in Vibrio cholerae (11). The plasmid insert in another, clone 1053, contains the promoter for iha, a gene not present in the K-12 E. coli strain MG1655 but described in E. coli O157:H7 as the IrgA homolog adhesin (“iha”) (46). The iha locus in strain CFT073 has also been annotated as ORF R4, the “exogenous ferric siderophore receptor” on the basis of protein homology (26).

Metabolic enzymes.

Three clones carry genes with metabolic functions. One of these, clone 504, has the promoter for the sucAB operon. The product of sucAB forms, with that of lpd, the 2-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex, an enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (15). Another, clone 1218, carries the promoter for metA, which encodes the enzyme for the first committed step in the methionine synthesis (25). The promoter and initial 137 bases of gltB appear on the insert of a third, clone 957. The gltBDF operon encodes the large subunit of glutamate synthase.

Unknowns.

Clone 514 features the promoter for yqjH, an ORF of unknown function but, as noted above, with protein homology to a vibriobactin utilization protein. Two others, 508 and 606, carry promoters for ybdL and ydiJ, ORFs with no known function or homology.

Regulation.

The product of degS, whose promoter appears in clone 301, plays a regulatory role. This gene encodes a cytoplasmic membrane serine protease whose only known target is another inner membrane protein, RseA (3). RseA binds and represses σE, a sigma factor associated with the bacterial response to envelope stress (1). When RseA is degraded by DegS, σE is free to activate its regulon.

Mutant survival in mice.

Deletion mutants were made of the loci associated with the identified promoter regions, and deletions were replaced by an antibiotic resistance marker. If the promoters appeared to be linked to an operon, the first gene of that operon was mutated. In the case of clone 723, two mutants were made: CFT073 irp2 and CFT073 fyuA. The former gene encodes a yersiniabactin synthesis enzyme, whereas the latter encodes an outer membrane yersiniabactin uptake receptor. Both are transcribed from the same promoter in a long operon in the Yersinia enterocolitica high-pathogenicity island (HPI) (8). In the case of clone 301, the degS locus could not be deleted by the λ Red method, but a single crossover disruption mutation could be made (see above).

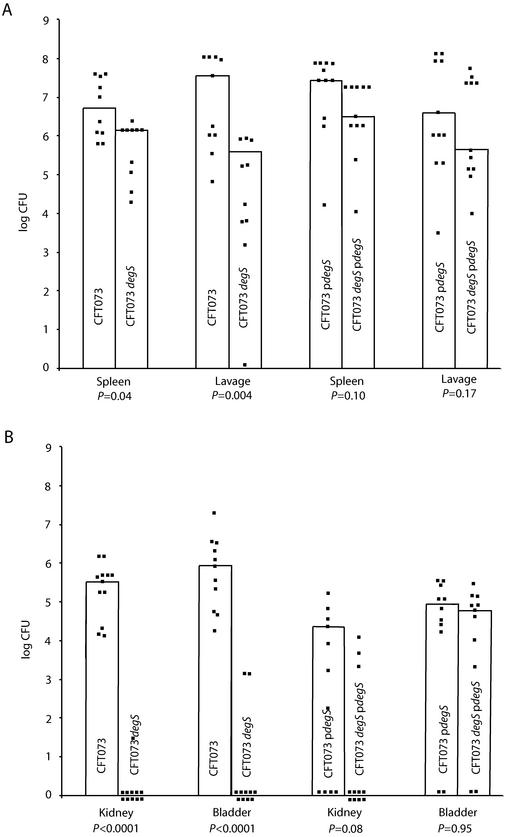

The mutants were inoculated into the mouse peritoneal cavity in competition with the wild type. Bacteria were recovered by culture of the lavage fluid and spleen after 6 h, and the relative numbers of mutant and wild type were compared. None of the mutants showed a statistically significant competitive disadvantage except CFT073 degS (WAM2853, Table 2). CFT073 degS recovery from the spleen and lavage fluid could be restored to that of the wild type by plasmid complementation of degS (Fig. 1A).

TABLE 2.

Survival of mutants compared to wild-type after mixed peritoneal infection of micea

| CFT073 mutation | Mutant vs wild-type spleens

|

Mutant vs wild-type lavage

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ratio | n | P | Ratio | n | P | |

| degS | 0.05 | 10 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 10 | 0.004 |

| sucA | 0.6 | 6 | 0.70 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.40 |

| yqjH | 1.1 | 6 | 0.99 | 1.0 | 6 | 0.93 |

| ybdH | 1.0 | 6 | 0.59 | 0.9 | 6 | 0.94 |

| ydiJ | 1.2 | 6 | 0.48 | 1.2 | 6 | 0.70 |

| irp2 | 1.3 | 6 | 0.31 | 1.4 | 6 | 0.18 |

| fyuA | 1.2 | 5 | 0.55 | 1.5 | 5 | 0.55 |

| gltB | 0.7 | 6 | 0.70 | 0.8 | 6 | 0.40 |

| iha | 1.3 | 6 | 0.81 | 1.1 | 6 | 0.81 |

| metA | 1.0 | 6 | 0.94 | 1.5 | 6 | 0.70 |

Ratio, recovered mutant/number of recovered wild-type CFU; n, number of mice; P, comparison as determined by Mann-Whitney U test.

FIG. 1.

Competitive infections in mice. Squares denote the CFU counts in individual mice. The bar height is the median number of CFU per gram (spleen, bladder, and kidney) or per milliliter (lavage fluid culture). (A) Wild-type versus CFT073 degS recovery from spleen and lavage fluid after a 1:1 mixed inoculation of the peritoneum. Recovery of wild type and mutant with plasmid-borne degS is also shown. (B) Wild-type versus CFTO73 (degS) recovery from bladder and kidney after mixed inoculation of bladder. Complemented strain recovery is also shown. P values were determined by using the Mann-Whitney U test.

The CFT073 degS mutant was also tested in a mouse model of ascending urinary tract infection. Here, relative numbers of mutant and wild type organisms were compared in bladder and kidney cultures made 2 days after transurethral inoculation. Again, the mutant showed diminished in vivo survival compared to wild type in both culture sites. Plasmid complementation (WAM2854) brought up CFT073 degS numbers in bladder cultures to match those of wild type. In the kidney, too, complementation with degS statistically improved mutant survival, but in many mice the complemented CFT073 degS strain could not be recovered from the kidneys (Fig. 1B).

CFT073 degS in vitro phenotypes.

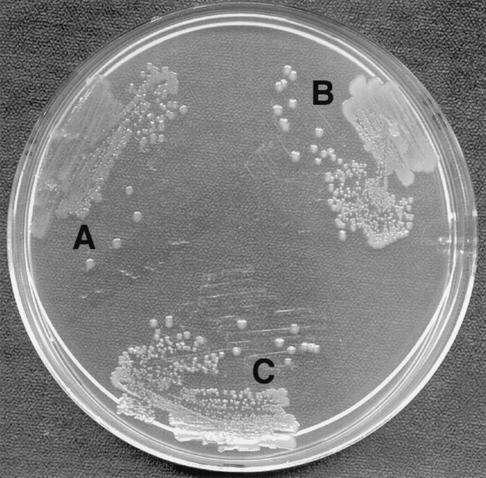

The degS mutant has a colony size and morphology similar to that of the wild type on LB agar and MacConkey medium. However, CFT073 degS colonies are more translucent than wild-type colonies (Fig. 2). Plasmid complementation restores colony opacity, so that the complemented degS mutant resembles the wild type (Fig. 2). The mutant and wild type are motile. Both agglutinate red blood cells and are equally hemolytic. No difference between the degS mutant and the wild type was detectable when LPS was compared on a silver-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel (data not shown). No difference was seen in serum sensitivity after exposure to 50% nonimmune human serum. The degS mutant grows as well in LB broth as does the wild type in the presence of polymyxin B (1.5 U/ml) or hydrogen peroxide (750 μM) (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Colony appearance on LB agar. (A) CFT073 degS; (B) CFT073 wild type; (C) CFT073 degS/pdegS.

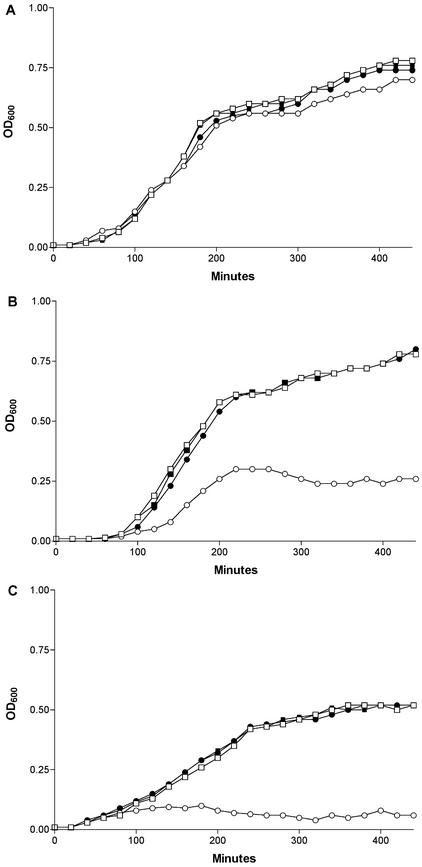

The growth kinetics of CFT073 degS do not, however, match those of the wild type in conditions of heat or ethanol stress. At 37°C in LB broth the growth curves are similar, but at 43°C the degS mutant shows a longer lag phase, a prolonged exponential phase, and a stationary-phase plateau lower than those of the wild type (Fig. 3B). Plasmid complementation of the degS mutant restores its growth curve to match that of the wild type. The addition of ethanol to LB broth (3% [vol/vol]) moderately impairs wild type but markedly impedes the growth of the degS mutant at 37°C (Fig. 3B). Again, plasmid complementation of the CFT073 degS mutant restores its growth kinetics to match those of wild type in 3% ethanol.

FIG. 3.

Growth curves in LB broth (average of three determinations) at 37°C (A), 43°C (B), or 37°C (C) in LB broth plus 3% ethanol. Symbols: □, wild-type CFT073; ▪, CFT073/pWAM2851; ○, CFT073 degS; •, CFT073 degS/pWAM2851.

DISCUSSION

The present study sought to examine the response at the genetic level of a pathogenic bacterium to its host environment. DFI was used, with sorting of clones directly from mouse peritoneal lavage fluid. Of eight pools of clones, 11 promoters in the extraintestinal E. coli strain CFT073 were found to be active in mouse peritonitis but relatively quiescent in LB medium.

This undoubtedly is not a complete list of in vivo-induced promoters. A major hindrance to the DFI technique in our system is the considerable amount of debris present in the mixture of bacteria and inflammatory peritoneal lavage fluid put through the cell sorter. Autofluorescent particles within the bacterial size range tested the discriminatory abilities of the FACS instrument. Of 10,000 “events” sorted as highly fluorescent, ca. 1,000 showed up in culture as viable bacteria. Even with successive high- and low-fluorescence sorting, most of the isolated clones did not demonstrate differential induction when tested individually in mice and broth. Thus, the combination of small bacterial size and background fluorescence pushes the limits of FACS capabilities and leads to errors and decreased sensitivity in sorting.

The same constraints limit the feasibility of using animal tissue to do the obverse of what was done here, that is, use of FACS to identify promoters that are active in LB culture but downregulated in mouse peritoneum. This is because the enrichment series to isolate such clones would require sorting nonfluorescent bacteria from the peritoneal fluid. The efficiency of FACS at this end of the fluorescence spectrum is particularly low due to the masking effect of background autofluorescence.

Technical issues such as these are probably the reason that almost all previous studies with DFI have been done with in vitro model systems. Nonetheless, despite its limitations, DFI in the present study provides a glimpse of the genetic response of a bacterium directly interacting with attack by the immune response and other environmental stresses inside the mouse.

Notable among the 11 in vivo-induced promoters is the number associated with iron acquisition genes. These include not only the three siderophores but also iha and yqjH, based on the homology as noted above. Thus, almost half of the 11 loci identified potentially relate to iron, a testament to the importance of this element, both as a nutrient and potentially as a signal to the pathogen of entry into the host.

As in other in vivo induction analyses, we found a variety of genes with metabolic functions. Why such “housekeeping” genes should be induced in vivo but not in vitro is in many cases not clear, but in some a particular stimulus can be postulated. For example, glutamate synthetase, the product of gltB, may be upregulated in response to nitrogen limitation in the mouse peritoneum (22). Homoserine transsuccinylase (the metA product) may be upregulated to maintain sufficient levels of this enzyme. In fact, this gene product, which catalyzes the first step of methionine synthesis, has been described as the most temperature-sensitive biosynthetic enzyme and, since it also is inactivated by stressors such as ethanol and cadmium, it has been suggested that MetA denaturation itself serves as an environmental sensor (9). The present study marks the third time suc has been identified by in vivo screening (12, 13). Why this tricarboxylic acid cycle component is upregulated inside a host is unclear. Bryk et al. showed that in Mycobacterium tuberculosis parts of the succinyltransferase complex can shunt reducing equivalents to sustain the specialized antioxidant defenses of the Mycobacterium (10). Whether a connection such as this between intermediary metabolism and pathogenesis exists in the Enterobacteriaceae has yet to be demonstrated.

Mutants were made of 9 of the 11 loci linked to the identified promoters. Two of the in vivo-induced genes, entC and iucB, have been studied in vivo previously (48) and were excluded from further analysis. Mutants at the nine other loci were tested in competition with the wild type in the mouse peritonitis model. In these infections, the only mutant showing attenuation was CFT073 degS.

The apparently undiminished virulence of the majority of the mutants may be a demonstration that redundant pathways exist for the functions carried out by their deficient gene products. The in vivo redundancy of iron uptake systems in strain CFT073 has been shown previously (48). In some cases, however, the lack of attenuation is surprising compared to studies in other bacterial strains. For example, the HPI present in CFT073 matches closely the island in Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis (41). This HPI contains the synthesis genes and uptake system for yersiniabactin, as well as a transcription regulator, YbtA. In Y. pestis, loss of the HPI has been shown to be associated with a marked increase in the 50% lethal dose when injected subcutaneously in mice (8). Similarly, an extraintestinal E. coli strain producing yersiniabactin was significantly more lethal than an isogenic, synthesis-defective mutant when injected subcutaneously into mice (44). However, in CFT073 deletion of the first gene of the synthesis operon, irp2, or deletion of the yersiniabactin uptake receptor gene, fyuA, had no effect on mutant survival compared to wild type in the first 6 h of mouse peritoneal infection (Table 2). This suggests either that CFT073 is different from other extraintestinal E. coli strains or that animal virulence assays have different sensitivities.

The only mutant significantly outcompeted by the wild type in peritoneal infection is CFT073 degS. The degS mutant was further tested in competition with the wild type in the mouse urinary tract. Here, too, it is attenuated, as measured by its recovery compared to that of wild type in bladder and kidney cultures. Complementation of the mutant with full-length degS on a plasmid significantly improves its in vivo survival.

DegS plays a major role in the central event of σE regulation, the degradation of RseA. Liberation of σE from RseA inner membrane repression frees it to activate its regulon, which includes rpoE, the gene for σE. In E. coli K-12 strains, rpoE is essential, and degS, too, is essential (3, 18). The failure of linear recombination to delete the degS locus in CFT073 may reflect its essential nature in this pathogenic E. coli strain as well. However, functional disruption was accomplished by recombination into degS of a plasmid introduced by conjugation. This suggests that degS may not be essential in CFT073 or that this gene disruption method is more permissive, allowing the emergence of mutants with secondary, suppressor mutations.

The CFT073 degS mutant studied here, therefore, may well contain a second, uncharacterized mutation. The nature of this mutation is that it permits the mutant to grow in rich medium at 37°C. The mutant also is tolerant of oxidative stress, unlike σE mutants in other bacterial species (47). The mutant does not, however, tolerate heat or ethanol stress as well as the wild type, nor does it appear to tolerate the in vivo stress of peritoneal or urinary tract infection. All of the these deficits can be restored by degS complementation, so the secondary mutation, if there is one, only partially compensates for the loss of DegS function.

The regulon of σE in a K-12 E. coli strain in one study was found to contain 25 promoters (16). Almost half of these were linked to genes of unknown function. The remainder were linked to transcription factors (rpoE, rpoH, and rpoD), periplasmic folding enzymes, and LPS biogenesis enzymes. Some of these genes (e.g., rpoH and rpoD) are transcribed from multiple promoters. Two members of the regulon, yqjA and yaeL, have been found to be essential. The function of yqjA remains unknown, but the product of yaeL was reported last year to be, like DegS, an RseA degradase (2, 31). Thus, degradation of the σE repressor, RseA, appears to be a two-step process (2). Interestingly, yaeL was recently found among genes in a cDNA-based screen of avian E. coli genes upregulated during infection of chickens (21).

The degradation of RseA by DegS (and YaeL) is necessary for the release of σE and activation of the σE regulon. The genes needed for virulence would therefore appear to be one or more members of that regulon. Of the genes in E. coli K-12 described thus far as σE dependent, none are known virulence genes per se (16). However, nine remain unknown, and the σE regulon could be larger or different in CFT073, so further characterization is needed of the function and extent of genes regulated by σE in this strain.

σE has previously been implicated in virulence, but not in E. coli. In S. enterica serovar Typhimurium and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae, σE has been found to be necessary for survival inside macrophages (14, 29). In V. cholerae σE is needed for survival inside the intestine (33). In Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgU (σE) is needed to counter hyperosmolar, oxidative, and heat stresses (38, 54). AlgU also activates the expression of genes needed for alginate production, a secreted polysaccharide required for bacterial persistence in human lungs (38). Alginate therefore serves as an example of a well-established virulence factor linked to σE.

Envelope stress, like iron depletion, may serve as a signal to the pathogen that it has entered its host or changed locales within the host. Transduction of this signal could trigger specialized pathways involved in virulence. Hung et al. found that CpxR activates transcription of the pap gene cluster, the synthesis and assembly genes of the P pilus. These investigators also report that it may increase the transcription of other virulence factors, since they see putative CpxR binding sites upstream of genes for hemolysin, cytotoxic necrotizing factor, and type 1 pili (30). This regulator, which with CpxA transduces signals of envelope stress, is thus linked to genes on pathogenicity islands. Whether the transmission of similar information by DegS and σE activates virulence mechanisms in E. coli will be a subject for further study in this laboratory.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants AI01583 and AI39000 from the National Institutes of Health.

Editor: A. D. O'Brien

REFERENCES

- 1.Ades, S. E., L. E. Connolly, B. M. Alba, and C. A. Gross. 1999. The Escherichia coli σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response is controlled by the regulated proteolysis of an anti-sigma factor. Genes Dev. 13:2449-2461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alba, B. M., J. A. Leeds, C. Onufryk, C. Z. Lu, and C. A. Gross. 2002. DegS and YaeL participate sequentially in the cleavage of RseA to activate the σE-dependent extracytoplasmic stress response. Genes Dev. 16:2156-2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alba, B. M., H. J. Zhong, J. C. Pelayo, and C. A. Gross. 2001. degS (hhoB) is an essential Escherichia coli gene whose indispensable function is to provide sigma activity. Mol. Microbiol. 40:1323-1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allaway, D., N. A. Schofield, M. E. Leonard, L. Gilardoni, T. M. Finan, and P. S. Poole. 2001. Use of differential fluorescence induction and optical trapping to isolate environmentally induced genes. Environ. Microbiol. 3:397-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badger, J. L., C. A. Wass, and K. S. Kim. 2000. Identification of Escherichia coli K1 genes contributing to human brain microvascular endothelial cell invasion by differential fluorescence induction. Mol. Microbiol. 36:174-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bartilson, M., A. Marra, J. Christine, J. S. Asundi, W. P. Schneider, and A. E. Hromockyj. 2001. Differential fluorescence induction reveals Streptococcus pneumoniae loci regulated by competence stimulatory peptide. Mol. Microbiol. 39:126-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer, M. E., and R. A. Welch. 1997. Pleiotropic effects of a mutation in rfaC on Escherichia coli hemolysin. Infect. Immun. 65:2218-2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bearden, S. W., J. D. Fetherston, and R. D. Perry. 1997. Genetic organization of the yersiniabactin biosynthetic region and construction of avirulent mutants in Yersinia pestis. Infect. Immun. 65:1659-1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biran, D., N. Brot, H. Weissbach, and E. Z. Ron. 1995. Heat shock-dependent transcriptional activation of the metA gene of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 177:1374-1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryk, R., C. D. Lima, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, and C. Nathan. 2002. Metabolic enzymes of mycobacteria linked to antioxidant defense by a thioredoxin-like protein. Science 295:1073-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butterton, J. R., and S. B. Calderwood. 1994. Identification, cloning, and sequencing of a gene required for ferric vibriobactin utilization by Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 176:5631-5638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camilli, A., and J. J. Mekalanos. 1995. Use of recombinase gene fusions to identify Vibrio cholerae genes induced during infection. Mol. Microbiol. 18:671-683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakrabortty, A., S. Das, S. Majumdar, K. Mukhopadhyay, S. Roychoudhury, and K. Chaudhuri. 2000. Use of RNA arbitrarily primed-PCR fingerprinting to identify Vibrio cholerae genes differentially expressed in the host following infection. Infect. Immun. 68:3878-3887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig, J. E., A. Nobbs, and N. J. High. 2002. The extracytoplasmic sigma factor, σE, is required for intracellular survival of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in J774 macrophages. Infect. Immun. 70:708-715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cronan, J. E., and D. Laporte. 1996. Tricarboxylic acid cycle and glyoxylate bypass, p. 208-211. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 16.Dartigalongue, C., D. Missiakas, and S. Raina. 2001. Characterization of the Escherichia coli σE regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 276:20866-20875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:6640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Las Penas, A., L. Connolly, and C. A. Gross. 1997. σE is an essential sigma factor in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:6862-6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Lorenzo, V., A. Bindereif, B. H. Paw, and J. B. Neilands. 1986. Aerobactin biosynthesis and transport genes of plasmid ColV-K30 in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 165:570-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donnenberg, M., and R. A. Welch. 1996. Virulence determinants of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 21.Dozois, C. M., F. Daigle, and R. Curtiss III. 2003. Identification of pathogen-specific and conserved genes expressed in vivo by an avian pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100:247-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ernsting, B. R., J. W. Denninger, R. M. Blumenthal, and R. G. Matthews. 1993. Regulation of the gltBDF operon of Escherichia coli: how is a leucine-insensitive operon regulated by the leucine-responsive regulatory protein? J. Bacteriol. 175:7160-7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foxman, B., R. Barlow, H. D'Arcy, B. Gillespie, and J. D. Sobel. 2000. Urinary tract infection: self-reported incidence and associated costs. Ann. Epidemiol. 10:509-515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gehring, A. M., I. I. Mori, R. D. Perry, and C. T. Walsh. 1998. The nonribosomal peptide synthetase HMWP2 forms a thiazoline ring during biogenesis of yersiniabactin, an iron-chelating virulence factor of Yersinia pestis. Biochemistry 37:17104.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greene, R. C. 1996. Biosynthesis of methionine, p. 542-560. In F. C. Neidhardt, R. Curtiss III, J. L. Ingraham, E. C. C. Lin, K. B. Low, B. Magasanik, W. S. Reznikoff, M. Riley, M. Schaechter, and H. E. Umbarger (ed.), Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology, 2nd ed. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 26.Guyer, D. M., J. S. Kao, and H. L. Mobley. 1998. Genomic analysis of a pathogenicity island in uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073: distribution of homologous sequences among isolates from patients with pyelonephritis, cystitis, and catheter-associated bacteriuria and from fecal samples. Infect. Immun. 66:4411-4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hitchcock, P. J., and T. M. Brown. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154:269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman, J. A., J. L. Badger, Y. Zhang, and K. S. Kim. 2001. Escherichia coli K1 purA and sorC are preferentially expressed upon association with human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 31:69-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Humphreys, S., A. Stevenson, A. Bacon, A. B. Weinhardt, and M. Roberts. 1999. The alternative sigma factor, σE, is critically important for the virulence of Salmonella typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 67:1560-1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hung, D. L., T. L. Raivio, C. H. Jones, T. J. Silhavy, and S. J. Hultgren. 2001. Cpx signaling pathway monitors biogenesis and affects assembly and expression of P pili. EMBO J. 20:1508-1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanehara, K., K. Ito, and Y. Akiyama. 2002. YaeL (EcfE) activates the σE pathway of stress response through a site-2 cleavage of anti-σE, RseA. Genes Dev. 16:2147-2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klerx, J. P., C. J. Beukelman, H. Van Dijk, and J. M. Willers. 1983. Microassay for colorimetric estimation of complement activity in guinea pig, human and mouse serum. J. Immunol. Methods 63:215-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kovacikova, G., and K. Skorupski. 2002. The alternative sigma factor σE plays an important role in intestinal survival and virulence in Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 70:5355-5362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lyon, M. W. 1917. A case of cystitis caused by Bacillus coli-hemolyticus. JAMA 69:353-358. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manges, A. R., J. R. Johnson, B. Foxman, T. T. O'Bryan, K. E. Fullerton, and L. W. Riley. 2001. Widespread distribution of urinary tract infections caused by a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli clonal group. N. Engl. J. Med. 345:1007-1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marra, A., J. Asundi, M. Bartilson, S. Lawson, F. Fang, J. Christine, C. Wiesner, D. Brigham, W. P. Schneider, and A. E. Hromockyj. 2002. Differential fluorescence induction analysis of Streptococcus pneumoniae identifies genes involved in pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 70:1422-1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marra, A., S. Lawson, J. S. Asundi, D. Brigham, and A. E. Hromockyj. 2002. In vivo characterization of the psa genes from Streptococcus pneumoniae in multiple models of infection. Microbiology 148:1483-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin, D. W., M. J. Schurr, H. Yu, and V. Deretic. 1994. Analysis of promoters controlled by the putative sigma factor AlgU regulating conversion to mucoidy in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: relationship to σE and stress response. J. Bacteriol. 176:6688-6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mobley, H. L., G. R. Chippendale, J. H. Tenney, R. A. Hull, and J. W. Warren. 1987. Expression of type 1 fimbriae may be required for persistence of Escherichia coli in the catheterized urinary tract. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:2253-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Opal, S. M., A. S. Cross, P. Gemski, and L. W. Lyhte. 1990. Aerobactin and alpha-hemolysin as virulence determinants in Escherichia coli isolated from human blood, urine, and stool. J. Infect. Dis. 161:794-796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rakin, A., S. Schubert, C. Pelludat, D. Brem, and J. Heesemann. 1999. The high-pathogenicity island of yersiniae, p. 77-90. In J. B. Kaper and J. Hacker (ed.), Pathogenicity islands and other mobile virulence elements. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, D.C.

- 42.Rasko, D. A., J. A. Phillips, X. Li, and H. L. Mobley. 2001. Identification of DNA sequences from a second pathogenicity island of uropathogenic Escherichia coli CFT073: probes specific for uropathogenic populations. J. Infect. Dis. 184:1041-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneider, W. P., S. K. Ho, J. Christine, M. Yao, A. Marra, and A. E. Hromockyj. 2002. Virulence gene identification by differential fluorescence induction analysis of Staphylococcus aureus gene expression during infection-simulating culture. Infect. Immun. 70:1326-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schubert, S., B. Picard, S. Gouriou, J. Heesemann, and E. Denamur. 2002. Yersinia high-pathogenicity island contributes to virulence in Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal virulence. Infect. Immun. 70:5335-5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seubert, A., R. Schulein, and C. Dehio. 2002. Bacterial persistence within erythrocytes: a unique pathogenic strategy of Bartonella spp. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 291:555-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarr, P. I., S. S. Bilge, J. C. Vary, Jr., S. Jelacic, R. L. Habeeb, T. R. Ward, M. R. Baylor, and T. E. Besser. 2000. Iha: a novel Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence-conferring molecule encoded on a recently acquired chromosomal island of conserved structure. Infect. Immun. 68:1400-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Testerman, T. L., A. Vazquez-Torres, Y. Xu, J. Jones-Carson, S. J. Libby, and F. C. Fang. 2002. The alternative sigma factor σE controls antioxidant defences required for Salmonella virulence and stationary-phase survival. Mol. Microbiol. 43:771-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Torres, A. G., P. Redford, R. A. Welch, and S. M. Payne. 2001. TonB-dependent systems of uropathogenic Escherichia coli: aerobactin and heme transport and TonB are required for virulence in the mouse. Infect. Immun. 69:6179-6185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tummuru, M. K., T. J. Brickman, and M. A. McIntosh. 1989. The in vitro conversion of chorismate to isochorismate catalyzed by the Escherichia coli entC gene product: evidence that EntA does not contribute to isochorismate synthase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 264:20547-20551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valdivia, R. H., and S. Falkow. 1996. Bacterial genetics by flow cytometry: rapid isolation of Salmonella typhimurium acid-inducible promoters by differential fluorescence induction. Mol. Microbiol. 22:367-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Valdivia, R. H., and S. Falkow. 1997. Fluorescence-based isolation of bacterial genes expressed within host cells. Science 277:2007-2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warren, J. 1996. Clinical presentations and epidemiology of urinary tract infections. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 53.Welch, R. A., V. Burland, G. Plunkett, 3rd, P. Redford, P. Roesch, D. Rasko, E. L. Buckles, S. R. Liou, A. Boutin, J. Hackett, D. Stroud, G. F. Mayhew, D. J. Rose, S. Zhou, D. C. Schwartz, N. T. Perna, H. L. Mobley, M. S. Donnenberg, and F. R. Blattner. 2002. Extensive mosaic structure revealed by the complete genome sequence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:17020-17024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu, H., M. J. Schurr, and V. Deretic. 1995. Functional equivalence of Escherichia coli σE and Pseudomonas aeruginosa AlgU: E. coli rpoE restores mucoidy and reduces sensitivity to reactive oxygen intermediates in algU mutants of P. aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 177:3259-3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]