Abstract

The cleavage of human serum monomeric immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1) and human secretory IgA1 (S-IgA1) by IgA1 proteinase of Neisseria meningitidis and cleavage by the proteinase from Proteus mirabilis have been compared. For serum IgA1, both proteinases cleaved only the α chain. N. meningitidis proteinase cleaved only in the hinge. P. mirabilis proteinase sequentially removed the tailpiece, the CH3 domain, and the CH2 domain. The cleavage of S-IgA1 by N. meningitidis proteinase occurred only in the hinge and was as rapid as that of serum IgA1. P. mirabilis proteinase predominantly cleaved the secretory component (SC) of S-IgA1. The SC of S-IgA1, whether cleaved or not, appeared to protect the α1 chain. Purified Fc fragment derived from the cleavage of serum IgA1 by N. meningitidis proteinase stimulated a respiratory burst in neutrophils through Fcα receptors, whereas the (Fcα1)2-SC fragment from digested S-IgA1 did not. The loss of the tailpiece from serum IgA1 treated with P. mirabilis proteinase had little effect, but the loss of the CH3 domain was concurrent with a rapid loss in the ability to bind to Fcα receptors. S-IgA1 treated with P. mirabilis proteinase under the same conditions retained the ability to bind to Fcα receptors. The results are consistent with the Fcα receptor binding site being at the CH2-CH3 interface. These data shed further light on the structure of S-IgA1 and indicate that the binding site for the Fcα receptor in S-IgA is protected by SC, thus prolonging its ability to activate phagocytic cells at the mucosal surface.

Human immunoglobulin A (IgA), which occurs in two isotypic forms, IgA1 and IgA2, is unlike other immunoglobulins in that it exists in a variety of molecular forms, each with a characteristic distribution in various body fluids (10, 22). Serum IgA, which is synthesized mainly in the bone marrow, is predominantly a monomer of IgA1 (160 kDa). This IgA is composed of two α1 chains, each of 60 kDa and containing one variable domain, a hinge region, and three constant domains (CH1, CH2, and CH3). The α1 chains are linked by disulfide bonds to each other and to two light chains (λ or κ chains) that are identical to those found in other immunoglobulins. In normal human serum, ca. 10% of the IgA comprises dimeric and higher polymeric forms. The proportion of IgA in these forms increases in a number of disease states (29). Dimeric and polymeric forms of IgA contain an additional protein known as J chain, which links the IgA monomers via the tailpiece—an 18-amino-acid extension of the α chain (22).

Secretory IgA (S-IgA) is the form of IgA synthesized at mucosal surfaces to protect them from microbial attack. S-IgA is dimeric or polymeric IgA complexed with a heavily glycosylated protein called the secretory component (SC). SC is part of a cell surface receptor that mediates the transport of polymeric IgA across the epithelial barrier (23). SC is thought to provide stability to the structure of S-IgA to increase its resistance to proteolytic degradation (10). Colostral S-IgA is composed of approximately equal proportions of S-IgA1 and S-IgA2, although the ratio differs in other secretions.

A number of important bacterial pathogens that invade mucosal surfaces, particularly species of Streptococcus, Haemophilus, and Neisseria, have the ability to cleave IgA (14, 33). The proteinases that they produce are highly specific and cleave, almost exclusively, IgA1 from humans and from higher apes at the hinge (27). Human IgA1 in its secretory form is also cleaved by them, suggesting that the hinge is not protected by SC. These IgA1 proteinases are unable to cleave IgA2 because it lacks the sequence of the IgA1 hinge. Although these IgA1 proteinases are extremely specific, recent studies have identified other, nonimmunoglobulin substrates susceptible to cleavage by them (8, 17, 35).

The IgA1 proteinases are believed to be virulence factors because they are produced in vivo (9, 15), convalescing patients have antibodies to them (2, 4, 5), and species of related organisms which are not pathogenic do not produce them (24, 28).

Proteus mirabilis is a common cause of urinary tract infections, particularly in young boys and elderly women (7, 31). Most strains of P. mirabilis of diverse types produce an EDTA-sensitive metalloproteinase which, unlike the IgA1 proteinases described above, is able to cleave not only IgA1 but also IgA2, IgG, and other, nonimmunoglobulin substrates (32, 18). The gene encoding this proteinase has been cloned and characterized (39). The proteinase is both produced and active in vivo in patients with P. mirabilis urinary tract infections (34) and is thought to play a significant role, along with other factors, in the virulence of the organism for the urinary tract (30, 38). P. mirabilis proteinase has been purified and characterized (19), and its action on IgG has been studied in detail (12). The enzyme is typical of a class of IgA-cleaving enzymes produced by a number of pathogens, including species of Pseudomonas, Serratia, and some parasites (reviewed in reference 15).

The aim of this study was to compare the actions on serum IgA1 and S-IgA1 of proteinases from P. mirabilis and Neisseria meningitidis, chosen as models of the two classes of IgA proteinases. These studies increase the understanding of the structural organization and functional activities of different parts of IgA. They may ultimately increase the understanding of the roles of these enzymes as virulence factors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria.

P. mirabilis strain 64676 serotype O28 was an isolate obtained from the urine of a patient with a urinary tract infection (32). Haemophilus influenzae strain R8 was a producer of a type 1 IgA1 proteinase, and N. meningitidis strain 3564 was a producer of a type 2 IgA1 proteinase. Both strains were isolated from clinical specimens obtained from local patients.

Proteinases.

The proteinase of P. mirabilis strain 64676 was purified from the filtrates (0.45- and 0.22-μm-pore-size filters) of the supernatant of 1 liter of a nutrient broth culture which had been incubated at 37°C for 48 h. Purification was done by affinity chromatography with a column (25 by 5 cm) of phenyl-Sepharose (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and then anion-exchange chromatography with a fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) Mono Q column (Pharmacia) as described previously (19). The purity and activity of the purified proteinase were confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and SDS-gelatin-PAGE as described previously (19). The IgA1 proteinases of H. influenzae and N. meningitidis were usually the supernatants of centrifuged suspensions of the bacteria in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 0.1% sodium azide that had been washed from growth on dialysis tubing membranes overlying solid culture media as described previously (32). In addition, a pure preparation of a type2 IgA1 proteinase from N. meningitidis strain HF13 was kindly donated by M. Kilian, Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark. This latter preparation gave the same results as the preparation from strain 3564.

Purification of serum monomeric IgA1 and S-IgA1.

Serum IgA1 was purified from fresh, pooled normal human serum (20). After clarification of the serum by filtration through glass wool and centrifugation, solid ammonium sulfate was added to the clear supernatant to 50% saturation, and the mixture was stirred for 3 h at 4°C. The precipitated proteins were collected by centrifugation at 23,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C, redissolved in distilled water, applied to a Sepharose 6B gel column, and eluted with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The fractions collected were analyzed by radial immunodiffusion (RID) to detect those containing IgA. The latter were subsequently analyzed by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions and immunoblotting. IgA-containing fractions were pooled and applied to a DEAE-Sephacel anion-exchange column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) to remove contaminating IgG which had been eluted from the Sepharose column by the buffer. IgA was then eluted from the Sephacel column at 0.1 to 0.2 M NaCl by the application of a 0 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient. Fractions containing pure IgA were identified by RID, pooled, and applied to a Jacalin-Sepharose column equilibrated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.1 mM CaC12 to separate IgA1 from IgA2 (19). The column was incubated at 4°C for 1 h to maximize IgA1 binding, and then PBS-CaCl2 was used to remove IgA2 by elution. The retained IgA1 was eluted with PBS containing 0.8 M galactose and concentrated by ultrafiltration. The purity of the IgA1 preparation was confirmed by RID, SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, gold staining, and immunoblotting. Some of the pure IgA1 was labeled with 125I by the chloramine-T method of Greenwood et al. (6).

S-IgA1 was purified from pooled human colostrum by a previously described method (11).

Δtp immunoglobulin.

Δtp was a pure recombinant chimeric IgA1 preparation of the mouse light-chain and variable heavy-chain domains and the human constant heavy-chain domain. The tailpiece was deleted through the introduction of a stop codon after CH3. Δtp was generously donated by J. M. Woof, Department of Molecular and Cellular Pathology, University of Dundee.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

SDS-PAGE was performed by the method of Laemmli (16) with a 4% acrylamide stacking gel over a 5 to 15% acrylamide gradient resolving gel. The upper tank buffer was 50 mM Tris containing 0.39% glycine and 0.1% SDS (pH 8.9), and the lower tank buffer was 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.1) containing 0.1% SDS. Samples were reduced by being boiled for 2 min with an equal volume of disruption buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 8 M urea, 2% SDS, and a trace of bromophenol blue dye) containing 80 mM dithiothreitol and then blocked by the immediate addition of iodoacetamide to 100 mM. Nonreduced samples were prepared by the addition of an equal volume of disruption buffer containing 40 mM iodoacetamide and boiling for 2 min. Samples were electrophoresed at 30 mA/gel in the cold until the dye front reached the bottom of the gels. The separated proteins were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes by electrophoresis with aqueous 25 mM Tris- 190 mM glycine containing 10% methanol at 4°C for 16 h at 10 V. The membranes were either stained with 0.2% Ponceau S dye in 3% trichloroacetic acid or washed in PBS containing 0.3% Tween 20 and stained with gold (Protogold; British Biocell International, Cardiff, United Kingdom); the positions of reference proteins were marked.

For immunoblotting, the membranes were blocked by agitation for 2 h in PBS containing 5% dried milk powder and then agitated for 2 h with 5% dried milk powder in PBS containing a 1/500 dilution of either alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human α or κ and λ chains (Sigma) or rabbit antibody to human SC (Dako Immunoglobulins, Copenhagen, Denmark). In the latter case, after extensive washing in PBS, the membranes were agitated for 2 h in PBS containing 5% dried milk powder and a 1/500 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (whole molecule) (Sigma). After further extensive washing in PBS, the membranes were developed in a buffer (100 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 9.5]) containing 0.33 mg of nitroblue tetrazolium/ml and 0.17 mg of bromochloroindolyl phosphate/ml.

The molecular mass markers used were maltose binding protein-galactosidase (175 kDa), maltose binding protein-paramyosin (83 kDa), glutamic dehydrogenase (62 kDa), aldolase (47.5 kDa), triosephosphate isomerase (32.5 kDa), β-lactoglobulin A (25 kDa), lysozyme (16.5 kDa), and aprotinin (6.5 kDa) (New England Biolabs, Hitchin, United Kingdom).

Digestion of immunoglobulins.

Pure immunoglobulin preparations were digested in a water bath at 37°C either with microbial proteinases in 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 0.04% sodium azide or with pepsin in 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.5). Reactions involving N. meningitidis proteinase were terminated by boiling, those involving P. mirabilis proteinase were terminated by the addition of disodium EDTA to 10 mM, and those involving pepsin were terminated by the addition of Tris to 200 mM.

For cleavage with P. mirabilis proteinase, 20 μl of IgA1 (4 mg/ml in PBS) was incubated for 4, 8, 16, 24, 48, and 72 h with 80 μl of pure proteinase (0.2 mg/ml in 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]), yielding an enzyme/substrate ratio of 1:5.

Chemiluminescence assays.

Pure serum monomeric IgA1 or colostral S-IgA1 (4 mg/ml in PBS) was digested with either P. mirabilis proteinase or pepsin (0.05 mg/ml) as described above at 37°C. At intervals over 72 h, 20-μl samples were removed and digestion was terminated by the addition of 2.5 μl of either 2 M Tris or 100 mM disodium EDTA. PBS (200 μl) was then added to each sample, 20 μl of the mixture was removed and saved for later analysis by SDS-PAGE, and aliquots of the remainder were added in duplicate or triplicate to wells of microtitration Luminometer plates (Dynatech). In other experiments, wells were coated in triplicate with 100 μl of either intact serum IgA1 or S-IgA1 or the Fc fragments produced by cleavage of IgA1 with N. meningitidis proteinase which had been purified by gel filtration with FPLC Superdex 200. After incubation of the plates overnight at 4°C and subsequent washing three times in PBS, 100 μl of Luminol (1.3 mg/20 ml of Hanks balanced salts solution [Gibco] containing 1 mg of bovine serum albumin/ml) (HBSS-BSA) and 50 μl of human neutrophils in HBSS-BSA (106/ml) were added to each well. The neutrophils had been purified from heparinized blood obtained from healthy volunteers by centrifugation with Ficoll-Hypaque as described previously (36). Luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence was measured by using a MicroLUMAT LB96 Luminometer (EG&G Berthold, Milton Keynes, United Kingdom) at 37°C for 60 min.

RESULTS

Proteinase action on human serum monomeric IgA1.

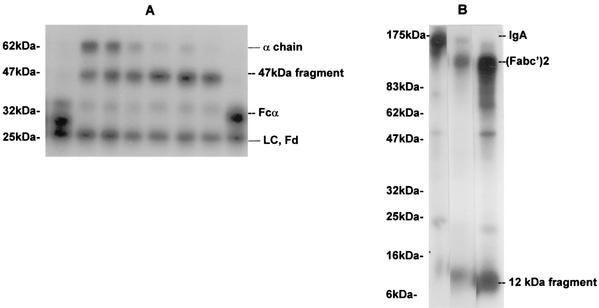

Under reducing conditions, cleavage of 125I-labeled serum IgA1 by pure P. mirabilis proteinase resulted in the formation of a major fragment of 47 kDa, which appeared to represent cleavage of the heavy chain between the CH2 and CH3 domains. There was no cleavage of the light chain (Fig. 1A). This pattern of cleavage was very different from the pattern resulting from cleavage of serum IgA1 by the IgA1 proteinases of H. influenzae and N. meningitidis, which cleaved the α1 chain only in the hinge region to give Fd and Fc fragments (Fig. 1A). Under the conditions used, the rate of cleavage of the α1 chain of serum IgA1 by the P. mirabilis proteinase was much slower than that given by the proteinases of H. influenzae and N. meningitidis. Prolonged incubation with the latter enzymes resulted in no further cleavage of the fragments, whereas prolonged incubation with large amounts of P. mirabilis proteinase resulted in the cleavage of the 47-kDa fragment to a 34-kDa fragment, probably representing the loss of the CH2 domain. When the products of cleavage of 125I-labeled serum IgA1 by the P. mirabilis proteinase were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, a large fragment of 140 kDa [F(abc′)2] and a small fragment of 12 kDa (CH3 domain) were observed (Fig. 1B). The large fragment was identical in mobility to that produced by the cleavage of IgA1 with pepsin, which is known to cleave at the CH2-CH3 interface (13).

FIG. 1.

Time course of cleavage of human serum IgA1 by various proteinases and pepsin. (A) Cleavage of radiolabeled human serum IgA1 by proteinases from P. mirabilis, H. influenzae, and N. meningitidis. 125I-labeled serum IgA1 was incubated at 37°C with proteinases from H. influenzae for 4 h (lane 1); P. mirabilis for 4, 8, 16, 24, 32, or 48 h (lanes 4 to 9, respectively); or N. meningitidis for 4 h (lane 8). Products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and detected by autoradiography. LC, light chain. Positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left. (B) Cleavage of radiolabeled human serum IgA1 by pepsin and P. mirabilis proteinase. 125I-labeled serum IgA1 was incubated at 37°C with buffer alone (lane 1), pepsin (lane 2), or P. mirabilis proteinase (lane 3) for 48 h. Products were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions and detected by autoradiography. Positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left.

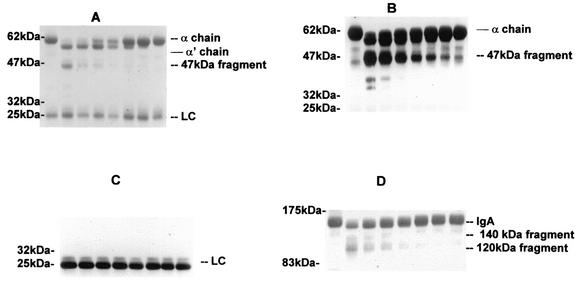

When a detailed analysis of the kinetics of cleavage and the products identified by immunoblotting was made, the P. mirabilis proteinase was shown to cleave the serum IgA1 α chain sequentially at different sites (Fig. 2A). The first cleavage, achieved by low concentrations of P. mirabilis proteinase, resulted in a reduction in the size of the α chain from 60 to ca. 57.5 kDa (α′). This fragment appeared to be formed through the removal of the tailpiece because it was similar in size to the α1 chain of the recombinant Δtp immunoglobulin, which lacks the tailpiece (Fig. 3C). On further incubation or with higher concentrations of P. mirabilis proteinase, the α1 chains of both IgA and Δtp immunoglobulin were cleaved further to yield a fragment of ca. 47 kDa and then, ultimately, one of 34 kDa; these fragments represent, respectively, removal of the CH3 domain and then the CH2 domain (results not shown). Our interpretation of the site of cleavage is based on the molecular masses of the fragments, the known sensitivity to proteolysis of sites between the domains, and the fact that the anti-α-chain antiserum used recognizes determinants predominantly in the Fab (CH1) region. The light chain was resistant to cleavage even on prolonged incubation with the proteinase (Fig. 2C). Upon analysis of the fragments by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions (Fig. 2D), IgA1 was seen to be cleaved to yield fragments of 140 and 120 kDa, corresponding to the fragment with the tailpiece deleted and the F(abc′)2 fragment (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 2.

Cleavage of human serum IgA1 by P. mirabilis proteinase. Aliquots of 80 μg of serum IgA1 in 20 μl of buffer were incubated for 72 h at 37°C with 20 μl of buffer alone (lane 1) or at 37°C with 20 μl of purified P. mirabilis proteinase at 0.2 mg/ml (lane 2) or as serial doubling dilutions (lanes 3 to 8). The products (10 μg of IgA1) were analyzed on 5 to 20% gradient polyacrylamide gels run under reducing (A to C) or nonreducing (D) conditions. After the transfer of proteins to nitrocellulose membranes, the blots were stained with Ponceau S dye (A and D) or incubated with anti-α chain (B) or anti-light chain (LC) (C) alkaline phosphatase-conjugated antibodies and developed.

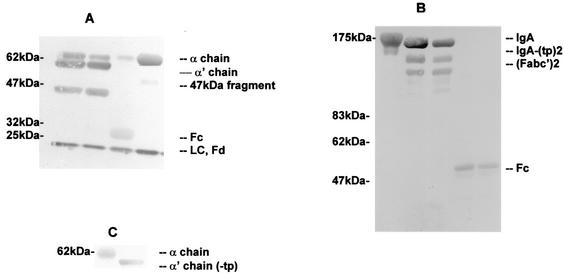

FIG. 3.

Cleavage of human serum IgA1 by purified proteinases from P. mirabilis and N. meningitidis. (A and B) Serum IgA1 was incubated at 37°C with buffer alone for 40 h (A, fourth lane; B, first lane), purified P. mirabilis proteinase for 24 and 40 h (A, first and second lanes; B, second and third lanes), or purified N. meningitidis proteinase for 8 h (A, third lane; B, fourth and fifth lanes). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing (A) or nonreducing (B) conditions and gold stained. LC, light chain. (C) Immunoblot of recombinant IgA1 (lane1) and recombinant IgA1 with the tailpiece deleted (−tp) (lane 2) analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions.

Incubation of human serum monomeric IgA1 with the purified type 2 IgA1 proteinase of N. meningitidis resulted in a single cleavage of the α1 chain at the hinge region and the formation of an Fc fragment of ca. 33 kDa and an Fd fragment of ca. 26 kDa which, under reducing conditions, ran close to the light chain (Fig. 3A, third lane). Under nonreducing conditions, the Fab and Fc fragments corresponded to peptides of ca. 48 and 60 kDa, respectively (Fig. 3B, fourth and fifth lanes). On extended incubation, further cleavage of the fragments was not observed.

Proteinase action on human S-IgA1.

When S-IgA1 was incubated with proteinase from N. meningitidis, the α1 chain was cleaved rapidly and at a rate similar to that for the cleavage of serum IgA1. N. meningitidis proteinase did not cleave the SC or the light chain (Fig. 4). When S-IgA1 cleavage was analyzed in detail by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and Western blotting, it was clear that the α1 chain was cleaved by the enzyme to produce fragments of ca. 33 and ca. 26 kDa (Fig. 4, sixth through eighth lanes), identical to those produced from serum IgA1 (Fig. 3A, third lane). Under the conditions in which the α1 chain of serum monomeric IgA1 was cleaved by P. mirabilis proteinase, the α1 chain of S-IgA1 was not cleaved (Fig. 4, second through fourth lanes). However, upon extended incubation with more enzyme, some of the α1 chain was cleaved to yield the 47-kDa fragment and ultimately the 34-kDa fragment (results not shown).

FIG. 4.

Cleavage of S-IgA1 by purified proteinases from P. mirabilis and N. meningitidis. S-IgA1 was incubated at 37°C with buffer alone for 40 h (first and fifth lanes); P. mirabilis proteinase for 8, 16, or 40 h (second through fourth lanes); or N. meningitidis proteinase for 2, 4, or 8 h (sixth to eighth lanes). Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and gold stained. LC, light chain.

Although the α1 chain was not cleaved as rapidly by P. mirabilis proteinase in S-IgA1 as in serum IgA1, the SC itself was cleaved from 82.5 to 79 kDa (Fig. 4). The SC in both its intact and its cleaved forms appeared to protect the sites on the α1 chain at which P. mirabilis proteinase normally cleaves. Again, the light chain remained intact.

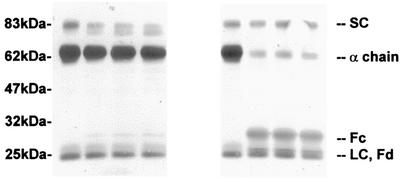

Effect of IgA cleavage on Fcα receptor binding.

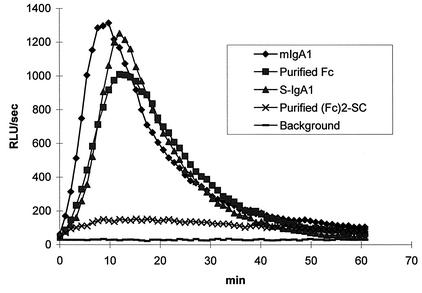

The effect of cleavage of different forms of IgA1 by microbial proteinases on the ability of the fragments to bind to Fcα receptors was assessed by chemiluminescence (Fig. 5 and 6). When serum monomeric IgA1 was cleaved by proteinase from N. meningitidis, there was but little loss of the ability of the product to stimulate a respiratory burst from neutrophils, suggesting that the Fc fragment remained fully functional in the assay used. This finding was confirmed by coating the plates with the gel filtration-purified Fcα1 fragment from the digestion. Both intact serum IgA1 and the Fcα1 fragment stimulated neutrophils to similar extents.

FIG. 5.

Stimulation of neutrophil chemiluminescence by human serum monomeric IgA1 (mIgA1), S-IgA1, and the Fc fragments derived from them by cleavage with N. meningitidis proteinase. Wells of microtiter plates were coated in triplicate with human serum monomeric IgA1, S-IgA1, or the Fc fragments produced by their cleavage with N. meningitidis proteinase which had been purified by gel filtration with FPLC Superdex 200. Luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence was measured at 37°C for 60 min after the addition of purified neutrophils. The traces show the mean values for triplicate samples. RLU, relative light units.

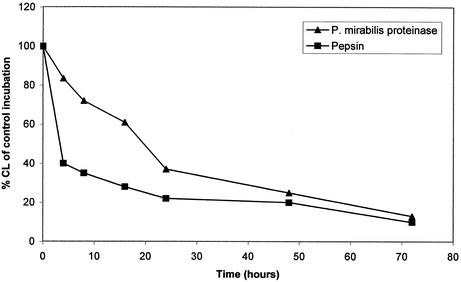

FIG. 6.

Effect of digestion of human serum IgA1 with pepsin or P. mirabilis proteinase on its ability to stimulate neutrophil chemiluminescence. Serum IgA1 was left untreated or was cleaved at 37°C for up to 72 h with pepsin at pH 4.5 or with P. mirabilis proteinase at pH 8.0. The products were bound in duplicate to microtiter plates before the addition of purified neutrophils and Luminol. The mean chemiluminescence (CL) was measured and calculated as a percentage of the value for the undigested serum control. The P. mirabilis proteinase had cleaved the tailpiece from IgA1 by 5 h as well as the CH3 domain by 24 h.

S-IgA1 stimulated neutrophils to the same extent as serum IgA1. However, the purified (Fcα1)2-SC fragment derived from S-IgA1 cleaved by N. meningitidis proteinase did not elicit a respiratory burst (Fig. 5).

When serum IgA1 was digested with pepsin, there was a rapid loss of its ability to trigger a respiratory burst in neutrophils (Fig. 6), indicating a loss of the ability of the cleaved IgA1 to bind to neutrophil Fcα receptors. SDS-PAGE analysis revealed that this loss was synchronous with the cleavage of IgA1 to the F(abc′)2 fragment. When serum IgA1 was digested with P. mirabilis proteinase, there was a complete loss of the tailpiece in the first 4 h but only a slight diminution in the ability to trigger a respiratory burst (Fig. 6). Later, as the IgA1 was being cleaved further to an F(abc′)2 fragment, there was an increasingly greater diminution in the ability to trigger a respiratory burst (Fig. 6). When S-IgA was incubated with P. mirabilis proteinase under the same conditions, there was no loss in the ability to trigger a respiratory burst in neutrophils, corresponding to the fact that under these conditions, the α1 chain was unaffected by this treatment, although SC was cleaved (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

IgA, particularly S-IgA, because of its role and as a consequence of its structure, is often considered the most resistant of all the immunoglobulins to proteolytic attack. However, IgA has been shown to be cleaved by proteinases from a number of pathogenic microorganisms. The proteinases from N. meningitidis and P. mirabilis are typical examples of two different classes of proteinases which have been shown to cleave IgA in vivo and in vitro. The former cleaves only human IgA1 and a few other, nonimmunoglobulin substrates (15), whereas the latter has proteolytic activity for a much broader range of substrates, including a variety of immunoglobulin types and other, nonimmunoglobulin substrates (18).

Although there is extensive evidence that IgA proteinases of both classes are secreted and are active at sites of infection, characterization of the activities of these enzymes has been largely restricted to studies of their activities for serum monomeric IgA1. This focus is somewhat artificial, since their activities are assumed to be most important at mucosal surfaces, where IgA is present in the form of S-IgA.

Our results confirm and extend the findings of Senior et al. (32) and Loomes et al. (18) that the proteinase of P. mirabilis cleaves the heavy chain of serum IgA1 at sites different from those cleaved by the IgA1 proteinases of pathogenic Haemophilus and Neisseria spp. The latter enzymes cleave the α1 chain exclusively in the hinge region to generate Fab and Fc fragments. In contrast, the P. mirabilis proteinase cleaves the α chain in serum IgA1 in a sequential manner, starting with the removal of the tailpiece, then the CH3 domain, and finally the CH2domain. Furthermore, unlike the Haemophilus and Neisseria proteinases, the P. mirabilis proteinase has the ability to cleave SC.

Kinetic studies showed that the rate of cleavage by the N. meningitidis proteinase of the α1 chain in serum IgA1 was similar to that in S-IgA1 and that the Fc fragment formed from the latter was in the form of (Fcα1)2-SC. In contrast, the rate of cleavage by the P. mirabilis proteinase of the α1 chain in serum IgA1 was considerably higher than that in S-IgA1. Thus, it appears that while the presence of the SC in S-IgA1 affords no protection to the α1 chain from cleavage by the N. meningitidis proteinase, SC, even in its cleaved form, still protects the α1 chain from cleavage by the P. mirabilis proteinase. The gels showed no evidence of asymmetrical cleavage of S-IgA1 by the Proteus proteinase (or the Neisseria proteinase), such as the α1 chain of one monomer but not the other being cleaved.

The site on IgA that binds to Fcα receptors has been characterized in detail (3, 26). In contrast to leukocyte IgG Fc receptors (FcγRI, FcγRII, and FcγRIII), which bind IgG at the hinge region, leukocyte IgA Fc receptors (FcαR/CD89) bind IgA at the CH2-CH3 interface. These data are consistent with the fact that human IgA1 and IgA2, which differ predominantly in the hinge, bind with similar affinities to FcαR and trigger similar responses through the receptor. These data do, however, appear to be at variance with observations (36, 21) that S-IgA1 and S-IgA2 bind to FcαR in spite of the presence of SC, which is suggested by some models of the structure of S-IgA1 to cover this binding region. Our interpretation of these data is to suggest that FcαR binds to S-IgA via one of the monomers, whereas binding to the other is obstructed by SC (21). However, the lack of detection of asymmetrically cleaved S-IgA1 after digestion with P. mirabilis protease suggests that each of the CH2-CH3 interfaces is equally inaccessible to the enzyme.

The consequence of IgA1 cleavage by the IgA1 proteases is the loss of the Fcα1 part of the molecule from the rest and thus the loss of mechanisms for the elimination of antigens. Moreover, the Fabα1 fragments remaining may mask relevant epitopes from the immune system and prevent the binding of intact antibodies of other isotyopes with more potential for killing (15).

Although the purified Fcα1 fragment resulting from the cleavage of serum IgA1 by the N. meningitidis proteinase clearly possesses the ability to trigger a respiratory burst in neutrophils when aggregated artificially by binding to plates, there are no known mechanisms for achieving such aggregation of Fc in vivo. Unexpectedly, the (Fcα1)2-SC fragment from the cleavage of S-IgA1 by the N. meningitidis proteinase was unable to stimulate a respiratory burst, suggesting a change in the conformation of the (Fcα1)2-SC fragment following cleavage from the Fab regions.

Although the removal of the tailpiece from serum IgA1 by the P. mirabilis proteinase did not prevent the truncated antibody from binding to FcαR and stimulating a respiratory burst, once there had been subsequent cleavage between the CH2 and CH3 domains, the ability to bind to FcαR was abolished. This results suggests that the binding of IgA to FcαR involves not only the primary binding site on CH2 but also determinants on CH3. This idea would give support to the observation of Pleass et al. (25) that the blocking of two loops at the CH2-CH3 interface by some streptococcal proteins prevented IgA from binding to the FcαR CD89 receptor and stimulating a respiratory burst.

It is frequently reported that one of the functions of SC is to protect S-IgA from cleavage by proteinases in the gut and elsewhere, but the evidence for this notion is limited. Our results show clearly that, in contrast to the situation where SC provides no protection to S-IgA1 from cleavage by the N. meningitidis proteinase, the sites in S-IgA1 between the CH3-tailpiece and the CH3-CH2 interfaces, vulnerable to cleavage by the P. mirabilis proteinase, are protected by SC. This scenario would be expected to allow S-IgA1 to retain its biological activity for a much longer time in the presence of P. mirabilis than in the presence of N. meningitidis. In addition, protection of the FcαR binding site by SC has the potential to prolong the ability of S-IgA1 to P. mirabilis to activate phagocytic cells at mucosal surfaces. SC appears to protect both α1 chains in the IgA1 molecule equally and to protect both IgA1 monomers in dimeric S-IgA1. It would therefore appear that fragments of IgA arising in vivo and detected in the urine of patients with P. mirabilis urinary tract infections (34) were derived from serum IgA rather than S-IgA.

Our data raise an interesting point that binding sites for FcαR and the Proteus protease, which appear to be closely related in serum IgA1, appear in S-IgA1 to be accessible to the receptor but not to the enzyme. This point can be explained if the site at the CH2-CH3 interface required for binding to FcαR is close to but not identical to that which is cleaved by the P. mirabilis proteinase and which is protected by the SC. However, the possibility that cleavage of the S-IgA molecule might be followed by a conformational change cannot be excluded. Indeed, the observation that the (Fcα1)2-SC fragment from the cleavage of S-IgA1 by the N. meningitidis proteinase is unable to elicit a respiratory burst from neutrophils through FcαR, whereas the intact molecule can, does suggest that this possibility is the case.

Models of serum IgA structures have been based on those of IgG because there are no crystallographic structures for IgA, other than for the Fab region of a mouse IgA (37). However, recent models of the structure of serum monomeric IgA1 based on solution-scattering methods (1) suggest a predominantly T-shaped rather than Y-shaped molecule, with the tailpiece binding back across the Fc region rather that extending away from the Fc region, as is often drawn. This arrangement implies that both the Fab region and the tailpiece interact with the Fc region. Models of S-IgA have been based largely on electron microscopy and, until recently, there has been much controversy about the mode of association of the individual components of the molecule. Models of S-IgA showing the SC covering both Fc regions appear to be incorrect, since S-IgA is able to bind to FcαR. However, the SC clearly offers considerable protection of the Fc region to proteolysis. It should, however, be remembered that S-IgA is a highly asymmetrical molecule. J chain is covalently bound to only two of the four α chains; the other two bind to each other. The single SC molecule binds covalently to only one of the four α chains and must associate in a different manner with the two IgA monomers. It is clear that a fuller explanation of these observations must await a more detailed understanding of the structures of the different forms of IgA, which at present are poorly understood.

Editor: J. D. Clements

REFERENCES

- 1.Boehm, M. K., J. M. Woof, M. A. Kerr, and S. J. Perkins. 1999. The Fab and Fc fragments of IgA1 exhibit a different arrangement from that in IgG: a study by X-ray and neutron solution scattering and homology modelling. J. Mol. Biol. 286:1421-1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks, G. F., C. J. Lammel, M. S. Blake, B. Kusecek, and M. Achtman. 1992. Antibodies against IgA protease are stimulated both by clinical disease and asymptomatic carriage of serogroup A Neisseria meningitidis. J. Infect. Dis. 166:1316-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carayannopoulos, L., J. M. Hexam, and J. D. Capra. 1996. Localization of the binding site for the monocyte immunoglobulin (Ig) A-Fc receptor (CD89) to the domain boundary between Calpha2 and Calpha3 in human IgA1. J. Exp. Med. 183:1579-1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devenyi, A. G., A. G. Plaut, F. J. Grundy, and A. Wright. 1993. Post-infectious human serum antibodies inhibit IgA1 proteinases by interaction with the cleavage site specificity determinant. Mol. Immunol. 30:1243-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilbert, J. V., A. G. Plaut, B. Longmaid, and M. E. Lamm. 1983. Inhibition of microbial IgA proteases by human secretory IgA and serum. Mol. Immunol. 20:1039-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenwood, F. C., W. M. Hunter, and J. S. Glover. 1963. The preparation of I131-labelled human growth hormone of high specific radioactivity. Biochem. J. 89:114-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hallett, R. J., L. Pead, and R. Maskell. 1976. Urinary infection in boys. A three year prospective study. Lancet 2:1107-1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hauck, C. R., and T. F. Meyer. 1997. The lysosomal/phagosomal membrane protein h-lamp-1 is a target of the IgA1 protease of Neissseria gonorrhoea. FEBS Lett. 405:86-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Insel, R. A., P. Z. Allen, and I. D. Berkowitz. 1982. Types and frequency of Haemophilus influenzae IgA1 proteases. Semin. Infect. Dis. 4:225-231. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerr, M. A. 1990. The structure and function of human IgA. Biochem. J. 271:285-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kerr, M. A., L. M. Loomes, B. C. Bonner, A. B. Hutchings, and B. W. Senior. 1997. Purification and characterization of human serum and secretory IgA1 and IgA2 using Jacalin. Methods Mol. Med. 9:265-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kerr, M. A., L. M. Loomes, and B. W. Senior. 1995. Cleavage of IgG and IgA in vitro and in vivo by the urinary tract pathogen Proteus mirabilis. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 371A:609-611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr, M. A., L. M. Loomes, and R. Thorpe. 1994. Purification and fragmentation of immunoglobulins, p. 102-113. In M. A. Kerr and R. Thorpe (ed.), Immunochemistry. BIOS Scientific Publisher, Oxford, England.

- 14.Kilian, M., J. Reinholdt, H. Lomholt, K. Poulsen, and E. V. Frandsen. 1996. Biological significance of IgA1 proteases in bacterial colonization and pathogenesis: critical evaluation of experimental evidence. APMIS 104:321-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilian, M., and M. W. Russell. 1999. Microbial evasion of IgA functions, p. 241-251. In P. L. Ogra et al. (ed.), Mucosal immunology, 2nd ed. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 16.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin, L., P. Ayala, J. Larson, M. Mulks, M. Fukuda, S. R. Carlsson, C. Enns, and M. So. 1997. The Neisseria type 2 IgA1 protease cleaves LAMP1 and promotes survival of bacteria within epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 24:1083-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loomes, L. M., B. W. Senior, and M. A. Kerr. 1990. A proteolytic enzyme secreted by Proteus mirabilis degrades immunoglobulins of the immunoglobulin A1 (IgA1), IgA2, and IgG isotypes. Infect. Immun. 58:1979-1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loomes, L. M., B. W. Senior, and M. A. Kerr. 1992. Proteinases of Proteus spp.: purification, properties, and detection in urine of infected patients. Infect. Immun. 60:2267-2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loomes, L. M., W. W. Stewart, R. L. Mazengera, B. W. Senior, and M. A. Kerr. 1991. Purification and characterization of human immunoglobulin IgA1 and IgA2 isotypes from serum. J. Immunol. Methods 141:209-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazengera, R. L., and M. A. Kerr. 1990. The specificity of the IgA receptor purified from human neutrophils. Biochem. J. 272:159-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mestecky, J., I. Moro, and B. J. Underdown. 1999. Mucosal immunoglobulins, p. 133-152. In P. L. Ogra et al. (ed.), Mucosal immunology, 2nd ed. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, Calif.

- 23.Mostov, K. E. 1994. Transepithelial transport of immunoglobulins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 12:63-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plaut, A. G. 1983. The IgA proteases of pathogenic bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 37:603-622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pleass, R. J., T. Areschoug, G. Lindahl, and J. M. Woof. 2001. Streptococcal IgA-binding proteins bind in the Cα2-Cα3 interdomain region and inhibit binding of IgA to human CD 89. J. Biol. Chem. 276:8197-8204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pleass, R. J., J. I. Dunlop, C. M. Anderson, and J. M. Woof. 1999. Identification of residues in the CH2/CH3 domain interface of IgA essential for interaction with the human Fcα receptor (FcαR) CD 89. J. Biol. Chem. 274:23508-23514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu, J., G. P. Brackee, and A. G. Plaut. 1996. Analysis of the specificity of bacterial immunoglobulin A (IgA) proteases by a comparative study of ape serum IgAs as substrates. Infect. Immun. 64:933-937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reinholdt, J., and M. Kilian. 1997. Comparative analysis of immunoglobulin A1 protease activity among bacteria representing different genera, species, and strains. Infect. Immun. 65:4452-4459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts-Thomson, P. J., and K. Shepherd. 1990. Molecular Size heterogeneity of immunoglobulins in health and disease. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 79:328-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rozalski, A., Z. Sidorczyk, and K. Kotelko. 1997. Potential virulence factors of Proteus bacilli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:65-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Senior, B. W. 1979. The special affinity of particular types of Proteus mirabilis for the urinary tract. J. Med. Microbiol. 12:1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Senior, B. W., M. Albrechtsen, and M. A. Kerr. 1987. Proteus mirabilis strains of diverse type have IgA protease activity. J. Med. Microbiol. 24:175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Senior, B. W., L. M. Loomes, and M. A. Kerr. 1991. Microbial IgA proteases and virulence. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 2:200-207. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Senior, B. W., L. M. Loomes, and M. A. Kerr. 1991. The production and activity in vivo of Proteus mirabilis IgA protease in infections of the urinary tract. J. Med. Microbiol. 35:203-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Senior, B. W., W. W. Stewart, C. Galloway, and M. A. Kerr. 2001. Cleavage of the hormone human chorionic gonadotropin, by the type 1 IgA1 protease of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and its implications. J. Infect. Dis. 184:922-925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart, W. W., and M. A. Kerr. 1990. The specificity of the human neutrophil IgA receptor (Fc alpha R) determined by measurement of chemiluminescence induced by serum or secretory IgA1 or IgA2. Immunology 71:328-334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suh, S. W., T. N. Bhat, M. A. Navia, G. H. Cohen, D. N. Rao, S. Rudikoff, and D. R. Davis. 1986. The galactan-binding immunoglobulin Fab J539. An X-ray diffraction study at 2.6 Å resolution. Proteins 1:74-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker, K. E., S. Moghaddame-Jafari, C. V. Lockatell, D. Johnson, and R. Belas. 1999. ZapA, the IgA-degrading metalloprotease of Proteus mirabilis, is a virulence factor expressed specifically in swarmer cells. Mol. Microbiol. 32:825-836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wassif, C., D. Cheek, and R. Belas. 1995. Molecular analysis of a metalloprotease from Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 177:5790-5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]