Abstract

To explore the meaning and function of attachment organization during adolescence, its relation to multiple domains of psychosocial functioning was examined in a sample of 131 moderately at-risk adolescents. Attachment organization was assessed using the Adult Attachment Interview; multiple measures of functioning were obtained from parents, adolescents, and their peers. Seczurity displayed in adolescents' organization of discourse about attachment experiences was related to competence with peers (as reported by peers), lower levels of internalizing behaviors (as reported by adolescents), and lower levels of deviant behavior (as reported by peers and by mothers). Preoccupation with attachment experiences, seen in angry or diffuse and unfocused discussion of attachment experiences, was linked to higher levels of both internalizing and deviant behaviors. These relations generally remained even when other attachment-related constructs that had been previously related to adolescent functioning were covaried in analyses. Results are interpreted as suggesting an important role for attachment organization in a wide array of aspects of adolescent psychosocial development.

INTRODUCTION

An individual's attachment organization, reflected in characteristic strategies for processing affect and memories surrounding attachment experiences (Bowlby, 1969/1980), has been implicated in numerous aspects of functioning in both childhood and adulthood and now also appears to be readily transmitted across generations (Allen, Hauser, & Borman-Spurrell, 1996; Cowan, Cohn, Cowan, & Pearson, 1996; Crowell & Feldman, 1988; Elicker, Englund, & Sroufe, 1992; Kobak & Sceery, 1988; Lyons-Ruth, 1996; Pianta, Egeland, & Adam, 1996; Rosenstein & Horowitz, 1996; Sroufe, Schork, Motti, Lawroski, & LaFreniere, 1984; Sroufe, Carlson, & Shulman, 1993; van IJzendoorn, 1995; Waters, Merrick, Albersheim, & Treboux, 1995). In adolescence, unlike childhood and adulthood, the meaning and the import of the construct of attachment for social functioning is derived primarily from theoretical inference and from a few studies examining its correlates within unusual samples. Yet, attachment organization appears likely to be integrally related to a range of domains of psychosocial functioning in adolescence both because it reflects core aspects of the ways adolescents process affect in social relationships and because it is also likely to be associated with qualities of ongoing relationships with parents (Allen & Hauser, 1996; Allen & Land, in press). If attachment organization is indeed linked to social functioning in adolescence, it has the potential ultimately to help explain life-span and intergenerational continuities in problems in functioning that often appear in adolescence (e.g., delinquency, depression, and so forth) by suggesting an internal mechanism with demonstrated stability that may account for these continuities. Anchoring the construct of attachment within an adequate nomological net in adolescence is thus crucial to beginning to understand how life-span and intergenerational continuities in attachment organization and in related aspects of functioning are maintained and displayed during adolescence.

In this study, we assessed the connection between attachment organization and three major indices of adolescent psychosocial functioning: (1) competence in peer relationships, (2) presence of internalizing behavior problems such as depression and anxiety, and (3) presence of externalizing and delinquent behaviors. The potential theoretical linkages of attachment organization to each of these distinct indices of functioning, discussed below, suggests just how broad and deep the connections between attachment and psychosocial functioning may be in adolescence, although they have yet to receive substantial empirical scrutiny.

Formation of meaningful peer relationships is one of the developmental tasks of adolescence with possibly the strongest theoretical links to attachment behavior. Peer relationships increase markedly in intensity during adolescence and in some cases may themselves become attachment relationships (Ainsworth, 1989; Ainsworth & Marvin, 1995; Berndt, 1979; Bowlby, 1980). A secure attachment organization, which is characterized in adolescence and adulthood by coherence in talking about attachment-related experiences and affect, should permit similar experiences and affect in peer relationships to be processed more accurately. In contrast, the defensive exclusion of information or inability to integrate different types of information about attachment experiences that is characteristic of insecure organizations may lead to distorted communications and to negative expectations about others, which have been linked to problems in social functioning in other research (Cassidy, Kirsch, Scolton, & Parke, 1996; Dodge, 1993; Slough & Greenberg, 1990).

A related possibility is that insecure attachment organization may mark problematic ongoing difficulties in relationships with parents that make it difficult for the adolescent to move freely beyond these relationships to establish successful new relationships with peers (Gavin & Furman, 1996). If attachment is related to competence with peers, understanding whether the current parental relationship accounts for this relation becomes important. Prior research has linked attachment organization to functioning with peers in childhood (Elicker et al., 1992; Sroufe et al., 1993; Waters, Wippman, & Sroufe, 1979), and in a high-functioning college sample (Kobak & Sceery, 1988). Yet, no research has examined the link between attachment organization and competence with peers in adolescence nor considered the extent to which a current parental relationship may account for this link.

Internalizing behavior problems, such as anxiety and depression, may result from attachment insecurity in several ways. Insecure attachment organizations may reflect beliefs that one is unable to get attachment needs met by others or that one does not merit getting attachment needs met by others; these negative expectations appear similar to the feelings of low self-worth and negative explanatory styles that have been closely linked to depression (Cummings & Cicchetti, 1990; Kobak, Sudler, & Gamble, 1991). Similarly, some forms of anxiety, such as childhood separation anxiety, are also believed to stem from the negative evaluations of caregiver availability that are associated with an insecure attachment organization (Bowlby, 1973). The presence of negative evaluations of one's ability to get attachment needs met may thus serve as a mediator between insecurity and both anxiety and depression.

One type of insecurity, preoccupation with attachment experiences and behaviors, may also increase the likelihood that internalizing symptoms will be strongly expressed, because the expression of such symptoms may serve as an attachment behavior itself—a call for help from powerful others (Allen, Kuperminc, & Moore, in press; Dozier & Lee, 1995; Kobak & Cole, 1994). Preoccupation has been found to be more strongly linked to affective disorders than other types of insecurity in a sample of insecure, psychiatrically hospitalized adolescents (Rosenstein & Horowitz, 1996). Insecure and preoccupied attachment organizations have also distinguished the most depressed adolescents from within a sample of adolescents all of whom were experiencing at least somewhat elevated levels of depression (Kobak et al., 1991). These studies leave open the question of how attachment is related to internalizing behaviors in samples that also include nondistressed adolescents, and of the extent to which low self-worth may account for links between attachment insecurity and internalizing problems.

Externalizing and delinquent behaviors also appear likely to be related to adolescent attachment organization. Insecurity may lead to externalizing behavior by engendering anger and hostility toward parents that reduces their leverage in exercising appropriate behavioral controls over their adolescents, thus eliminating a major buffer against adolescent deviance (Allen et al., in press; Greenberg & Speltz, 1988; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989). Different types of insecure attachment may also have different relations with externalizing behaviors. Some theories of adolescent and adult criminality posit that such criminality reflects alienation, and devaluing of social relationships and of societal norms more generally (Gottfredson & Hirschi, 1990), which most resembles insecure attachment organizations characterized by dismissal of the importance of attachment. It is also possible, however, that delinquent activity may serve as a primitive form of communication to attachment figures of a need for help by adolescents who are preoccupied with attachment (Allen & Land, in press). In adolescent research, dismissing attachments have been more strongly linked to conduct disorders than preoccupied attachments in a sample of insecure, hospitalized adolescents (Rosenstein & Horowitz, 1996). Research at other stages of the life span has been inconclusive: In adulthood, insecure attachment has been linked to criminal behavior (Allen, Hauser, & Borman-Spurrell, 1996); yet, in childhood, researchers have only inconsistently found links from insecurity to child noncompliance (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978; Alexander, Waldron, Barton, & Mas, 1989; Lay, Waters, & Park, 1989; Russo, Cataldo, & Cushing, 1981; Sroufe et al., 1984; Waters et al., 1979). No studies have considered relations between attachment security and delinquent and externalizing behaviors in adolescence nor considered the possible interaction of attachment organization with parental behavioral control styles in predicting externalizing behavior problems.

This study examined multiple theoretical connections between attachment organization and adolescent psychosocial functioning in an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of moderately at-risk ninth and tenth graders. The sample was selected to allow assessments within a maximally meaningful range of psychosocial functioning, including substantial numbers of adolescents functioning both adequately and poorly. Assessments were designed so that each construct was evaluated from the perspective of the most objective rater in a position to observe it. Direct links of attachment organization to the major domains of functioning reviewed above were examined first. Following this, analyses examined whether observed links between attachment and social functioning could be accounted for by other theoretically related constructs with well-established links to functioning (i.e., adolescent perceived self-worth, quality of current maternal relationship, and degree of maternal control over adolescent behavior). This approach allows both a more stringent assessment of what is gained by using attachment theory to consider adolescent psychosocial functioning and an assessment of how attachment organization predicts functioning when considered in the context of these other factors.

METHOD

Participants

Data for the analyses in this study were collected from 131 ninth and tenth graders (66 male and 65 female), their mothers, and their peers. The mean age of the adolescents was 16.0 years (SD = 0.8), with a range from 14 to 18 years. The self-identified racial/ethnic background of the sample was 66% European American, 33% African American, and 1% other. Thirty-four percent of adolescents were living with both biological parents. The median family income was $25,000 (range was from less than $5,000 to greater than $60,000), and parents' median education level was a high school diploma with some training post-high school, with a range from less than an eighth grade education to completion of an advanced degree.

Adolescents were recruited through public school systems serving rural, suburban, and moderately urban populations. Ninth and tenth graders were selected for inclusion in the study based upon the presence of at least one of four possible academic risk factors, including failing a single course for a single marking period, any lifetime history of grade retention, 10 or more absences in one marking period, and any history of school suspension. These broad selection criteria were established to sample a sizable range of adolescents who could be identified from academic records as having the potential for future academic and social difficulties, including both adolescents already experiencing serious difficulties and those who are performing adequately with only occasional, minor problems. As intended, these criteria identified approximately one-half of all ninth- and tenth-grade students as eligible for the study.

Each teen also was asked to name several friends who knew him or her well; two of these peers were then recruited for the study for each teen. The mean age of peer participants was 16.2 years (SD = 1.3), with a range from 13 to 24 years. Peers had known participating teens for an average of 3.9 years (SD = 4.9 years).

Procedure

After adolescents who met study criteria were identified, letters were sent to each family of a potential participant explaining the investigation as an ongoing study of the lives of teens and families. These initial explanatory letters were then followed by phone calls to families who indicated a willingness to be further contacted. If both the teen and the parent(s) agreed to participate in the study, the family was scheduled to come to our offices for two 3 hr sessions. Approximately 50% of approached families agreed to participate. Families were paid a total of $105 for participation. At each session, active, informed consent was obtained from parents and teens. In the initial introduction and throughout both sessions, confidentiality was assured to all family members, and adolescents were told that their parents would not be informed of any of the answers they provided. Participants' data were protected by a Confidentiality Certificate issued by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services which protected information from subpoena by federal, state, and local courts. Transportation and child care were provided if necessary.

Active consent was obtained from both peers and parents of peers participating in the study. Peers were paid $10 to come in separately for a 1 hr session, during which they completed written questionnaires and used Q-sort techniques to rate the teens in the study. As with study participants, peers were assured that all information would be kept confidential and, in particular, were told that study participants would not learn of their questionnaire responses.

Measures

Adult Attachment Interview and Q-set (George, Kaplan, & Main, 1996; Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, Fleming, & Gamble, 1993)

This structured interview probes individuals' descriptions of their childhood relationships with parents in both abstract terms and with requests for specific supporting memories. For example, participants were asked to list five words describing their early childhood relationships with each parent and then to describe specific episodes that reflected those words. Other questions focused upon specific instances of upset, separation, loss, trauma, and rejection. Finally, the interviewer asked participants to provide more integrative descriptions of changes in relationships with parents and the current state of those relationships. The interview consisted of 18 questions and lasted 1 hr on average. Slight adaptations to the adult version were made to make the questions more natural and easily understood for an adolescent population (Ward & Carlson, 1995). Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed for coding.

The AAI Q-set (Kobak et al., 1993)

This Q-set was designed to closely parallel the Adult Attachment Interview Classification System (Main & Goldwyn, in press) but to yield continuous measures of qualities of attachment organization. The data produced by the system nevertheless can be reduced via an algorithm to classifications that largely agree with three-category ratings from the AAI Classification System (Borman-Spurrell, Allen, Hauser, Carter, & Cole-Detke, 1995; Kobak et al., 1993). Each rater reads a transcript and provides a Q-sort description by assigning 100 items into nine categories ranging from most to least characteristic of the interview, using a forced distribution. All interviews were blindly rated by at least two raters with extensive training in both the Q-sort and the Main Adult Attachment Interview Classification System.

These Q-sorts were then compared with dimensional prototype sorts for: secure versus anxious interview strategies, reflecting the overall degree of coherence of discourse, the integration of episodic and semantic attachment memories, and a clear objective valuing of attachment; preoccupied strategies, reflecting either rambling, extensive but ultimately unfocused discourse about attachment experiences or angry preoccupation with attachment figures; dismissing strategies, reflecting inability or unwillingness to recount attachment experiences, idealization of attachment figures that is discordant with reported experiences, and lack of evidence of valuing attachment; and deactivating versus hyperactivating strategies, which simply represents the overall balance of dismissing and preoccupied styles. These dimensions had been previously validated (Kobak et al., 1993), and using them, Kobak reports being able to capture classifications from the AAI classification system with good accuracy. The correlation of the 100 items of an individual's Q-sort with each dimension (ranging from −1.00 to 1.00) were then taken as the participant's scale score for that dimension. The Spearman-Brown reliabilities for the final scale scores were .84, .89, .82, and .91 for the secure, dismissing, preoccupied, and hyperactivating versus deactivating scales, respectively. Although this system was designed to yield continuous measures of qualities of attachment organization, rather than to replicate classifications from the Main and Goldwyn (in press) system, when scale scores were reduced to classifications in this study by simply using the largest Q-scale score above .20 as the primary classification (Kobak et al., 1993) and compared to a subsample (N = 76) of AAI's classified by an independent coder with well-established reliability in classifying AAI's (U. Wartner), 74% received identical codes (kappa = .56, p < .001), and 84% matched in terms of security versus insecurity (kappa = .68).

Social acceptance (peer report)

Peers completed a modified version of the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1988), as described above. The measure was modified so that peers completed it as they thought it best described the target teen in the study. Scores from the two peers who rated each participating teen were averaged to produce a peer social acceptance score for each teen. These untrained adolescent raters nevertheless produced ratings that correlated with each other surprisingly well (Spearman-Brown r = .63), and the resulting scale had good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = .84).

Internalizing behavior problems (self-report)

Youths completed the Youth Self-Report, a well-validated and normed measure of problematic adolescent behaviors (Achenbach, 1991). Adolescents were asked to rate how well a variety of descriptions of symptomatic behaviors applied to them during the previous 6 months, on a scale of 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very or often true. The internalizing behavior problems scale has been well validated and incorporates reports about problems such as depression, anxiety, and social withdrawal.

Externalizing behavior problems (maternal report)

Mothers reported their adolescents internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors using the 120-item Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). This measure has been widely used in research and clinical applications with samples of normal and clinically referred youths and shows good evidence of reliability and validity (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1979, 1981). Mothers responded to how well each item described their adolescent on a 3 point scale ranging from “Not true” to “Very true or often true.”

Delinquency (peer report)

To obtain peers' ratings of adolescents' delinquent behavior, six items were assessed using the format of the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1988), to reduce effects of social desirability. These items, which were averaged to produce a 0–4 scale, focused upon the extent to which participants got into trouble at school, got into physical fights, assaulted other people, did things serious enough to get sent to jail or reform school, and had trouble getting along with both adults and peers. Peers demonstrated substantial agreement with one another (Spearman-Brown r = .70) for this scale, which showed good internal consistency (α = .79).

Perceived self-worth (self-report)

Adolescents completed the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile (Harter, 1988). For each item, two sentence stems were presented side by side, for example, “Some teenagers find it hard to make friends,” but “For other teenagers it's pretty easy.” Adolescents were asked to decide which stem best described them and whether the statement was “sort of true” or “really true” for them. This format was designed to reduce the effects of a pull for social desirability. The self-worth scale sums five items in a similar format, each assessing teens' satisfaction with themselves and the way they are leading their lives. Harter (1988) reports good psychometric characteristics for these scales. Internal consistency (Cronbach's α) for this sample was .86.

Quality of relationship with mother (self-report)

The Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987) was used to assess adolescents' perceptions of the current degree of trust, communication, and alienation in their relationships with their mothers. A composite score of the overall quality of this relationship is obtained from 25 5-point Likert scale items. This composite measure has been shown to have good test-retest reliability and has been related to other measures of family environment and teen psychosocial functioning (Armsden & Greenberg, 1987), although it is not a proxy for security of attachment organization (Crowell, Treboux, & Waters, 1993). Cronbach's α in this sample was .95 for the composite score.

Parental control of teens' behavior (maternal report)

Mothers completed this measure, originally designed by Baumrind (1991) and subsequently revised and further validated by Hetherington and Clingempeel (1992). This study used a scale for mothers' perception of their actual control over their teenagers' behavior in a variety of contexts. The questions focus on teens' friends, intellectual interests, school activities, sexual behavior, health habits, substance use, and extracurricular activities. Cronbach's α in this sample was .89.

RESULTS

Preliminary Analyses

Sample means

Means and standard deviations of all measures used are presented in Table 1. For the Child Behavior Checklist, which has published norms for both clinical and nonclinical samples, mean scores are approximately twice as high as norms for nonclinical samples and, yet, 50% lower than norms for clinical populations (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). These means are thus consistent with the moderately at-risk nature of the sample. Scores on attachment scales were roughly comparable to scores from the one other normative sample of adolescents reported in the literature (Kobak et al., 1993).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Attachment and Outcome Variables

| Measures | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Attachment measures: | ||

| Security | .23 | .38 |

| Preoccupation | .04 | .21 |

| Dismissal of attachment | .11 | .41 |

| Psychosocial functioning: | ||

| Social acceptance (peer report) | 3.04 | .65 |

| Internalizing behaviors (self-reported) | 13.72 | 9.34 |

| Externalizing behaviors (maternal report) | 15.43 | 10.48 |

| Delinquency (peer report) | 1.88 | .60 |

| Nonattachment predictors of functioning: | ||

| Quality of relationship | 90.72 | 19.75 |

| Perceived self-worth | 3.09 | .72 |

| Maternal control of behavior | 26.82 | 7.77 |

Note: Ns for all measures except peer-report measures range from 116 to 131 due to missing data. Ns for peer-report measures are 107.

Demographic effects

Analyses examined the relation of both attachment measures and indices of social functioning to adolescents' gender, self-identified racial/ethnic background, age, family composition (nondivorced two-parent family versus other family types), and parents' income. Results indicated effects beyond those expected by chance only for adolescents' gender, racial/ethnic minority status, and family income. These three demographic factors were thus entered into all analyses predicting adolescent functioning so as to make sure that any attachment effects obtained were not simply artifacts of demographic differences in the sample. These demographic effects are reported along with other analyses below.

Interactions of the demographic factors with the relation of attachment to indices of social functioning were also assessed, to examine whether findings reported were truly applicable across different demographic groups of adolescents examined (e.g., males versus females, and so on). Interactions in this study were assessed by standardizing the two variables of interest and taking their product as the interaction term. Such moderator effects were found only for predictors of externalizing and delinquent behaviors and are reported with those analyses.

Intercorrelations among measures of functioning

Correlations across the four different indices of functioning assessed (social competence, internalizing behaviors, externalizing behaviors, and delinquent behaviors) ranged in absolute value from r = .17 to r = .25 (with the exception of a somewhat higher correlation, r = .36, between maternal report of externalizing behaviors and peer report of serious delinquent behaviors). These modest correlations suggest that truly different aspects of functioning were being assessed across different domains.

Intercorrelations among attachment measures

The security scale was highly correlated with both the dismissing and hyperactivating versus deactivating scales, rs = −.93 and −.73. This finding reflected the relatively high proportion of dismissing attachment classifications 38% (relative to preoccupied classifications, 8%) in the sample. The scales for security and preoccupation were correlated at r = −.34. Because of the redundancy indicated by the high correlations among the security, dismissing, and hyperactivating scales, the dismissing and hyperactivating scales were not used in further analyses.

Primary Analyses

A twofold analytic strategy was employed. First, simple partial correlations of attachment security and preoccupation with the outcome in question were performed, partialing the three demographic factors previously identified (family income, a dummy variable for gender, and a dummy variable for membership in a racial/ethnic minority group). These data, along with unpartialed correlations, are presented for all outcomes in the study in Table 2 and indicate a range of correlations of attachment strategies and indices of functioning that will be discussed in detail below.

Table 2.

Correlations of Psychosocial Functioning Indices with Attachment Strategies (after Partialing Gender, Racial/Ethnic Status, and Family Income)

| Security |

Preoccupation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indices of Psychosocial Functioning | Partial r | r | Partial r | r |

| Social acceptance (peer report) | .34*** | .20* | −.17+ | −.11 |

| Internalizing behaviors (self-report) | −.21* | −.10 | .33*** | .38*** |

| Externalizing behaviors (maternal report) | −.24** | −.21* | .08 | .09 |

| Delinquency (peer report) | −.25** | −.32*** | .29** | .24** |

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Next, we examined the extent to which attachment organization would add to the explained variance in functioning measures over and above variance explained by three constructs (perceived self-worth, quality of maternal relationship, and maternal control over adolescent behavior) that have been previously linked to one or more of the measures of adolescent functioning being considered. Finally, relevant interaction effects were considered. For example, in a hierarchical regression predicting social acceptance by peers, we first entered a block of demographic factors, then entered the block of existing related measures. Security of attachment organization was entered next, followed by adolescent's use of preoccupied attachment strategies. Finally, relevant interactions of attachment with demographic factors or with the quality of the relationship with mother were examined in a final block. The final block of interactions was presented only when it significantly added to prediction of the outcome in question.

Social acceptance by peers

Partial correlations of attachment strategies with social acceptance reported in Table 2 indicate an effect of overall security in predicting peer-rated social acceptance, after accounting for effects of demographic characteristics. A trend toward a prediction of social acceptance by lower levels of preoccupation with attachment was also found. Analyses of results of hierarchical regressions, presented in Table 3, in which social acceptance was predicted after accounting for demographic factors, self-worth, quality of the maternal relationship and maternal control, indicated that security remained a predictor of social acceptance even after accounting for these other factors. After accounting for security, use of preoccupied strategies did not add additional explained variance.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Adolescent Social Acceptance from Adolescent Attachment Organization after Accounting for Related Covariates

| Social Acceptance (Peer-Reported) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| Predictors | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

| I: | |||

| Gender (1 = M, 2 = F) | .14 | … | … |

| Race (1 = European American, 2 = African American) | .14 | … | … |

| Family income | −.08 | … | … |

| … | .052 | .052 | |

| II: | |||

| Perceived self-worth (teen report) | .08 | … | … |

| Maternal control (maternal report) | −.05 | … | … |

| Relationship with mother (teen report) | .18 | … | … |

| … | .103 | .051 | |

| III: Security | .34** | .174** | .061** |

| IV: Preoccupation | −.01 | .174* | .000 |

Note: β weights are those taken from entry of variables into models. N = 103.

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Internalizing behaviors

Partial correlations of attachment and internalizing behaviors revealed an effect for security to be related to fewer self-reported internalizing symptoms and for preoccupation to be related to higher levels of internalizing symptoms. In initial stages of hierarchical regressions, reported in Table 4, gender predicted internalizing symptoms (females greater than males), and, as expected, perceived self-worth was also a predictor. After accounting for demographic and other factors that have been related to adolescent functioning, the relation of security to internalizing behaviors became nonsignificant, whereas preoccupation remained a predictor of higher levels of internalizing behaviors.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Adolescent Internalizing Symptoms from Adolescent Attachment Organization after Accounting for Related Covariates

| Internalizing Symptoms (Self-Report) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| Predictors | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

| I: | |||

| Gender (1 = M, 2 = F) | .28** | … | … |

| Race (1 = European American, 2 = African American) | −.09 | … | … |

| Family income | .01 | … | … |

| … | .087* | .087* | |

| II: | |||

| Perceived self-worth (teen report) | −.49*** | … | … |

| Maternal control (maternal report) | −.01 | … | … |

| Relationship with mother (teen report) | −.15+ | … | … |

| … | .402*** | .315*** | |

| III: Security | −.11 | .410*** | .008 |

| IV: Preoccupation | .28*** | .473*** | .063*** |

Note: β weights are those taken from entry of variables into models. N = 126.

p ≤ .10;

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01;

p ≤ .001.

Externalizing and delinquent behaviors

Partial correlations, reported in Table 2, indicate that after accounting for demographic factors, security was related to both peer and maternal reports of externalizing behaviors. Preoccupation was linked to peer reports but not to maternal reports. In regression analyses that examined predictions of externalizing behavior over and above predictions from demographic self-worth and maternal relationship measures, these main effects remained, except for the effect of security in predicting maternal report of teen externalizing behaviors, which dropped to the trend level. However, several moderator effects of security and preoccupation were detected in each analysis.

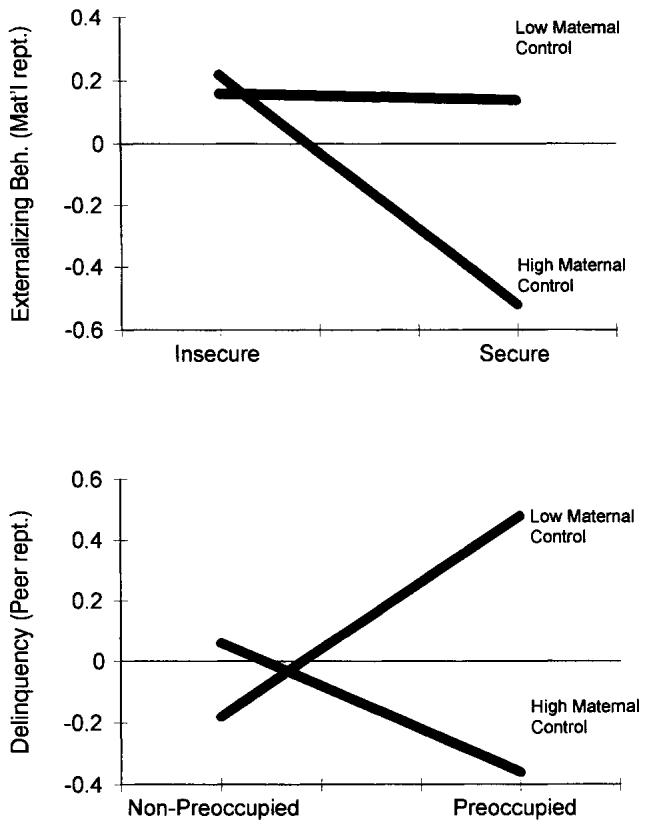

In predicting maternal reports of externalizing behaviors (see Table 5), the degree of maternal control over adolescent behavior interacted with both security and preoccupation. In these interactions (depicted in Figure 1) high maternal control was related to lower levels of externalizing behavior primarily for adolescents with secure or with more preoccupied attachment organizations. For insecure/nonpreoccupied adolescents, maternal control displayed relatively little relation to adolescent externalizing behavior. Examination of the preoccupation × income interaction (not depicted) revealed that preoccupation was more strongly related to delinquency in low-income families.

Table 5.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Maternal Reports of Externalizing Behaviors from Adolescent Attachment Organization after Accounting for Related Covariates

| Externalizing Behaviors (Maternal Report) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| Predictors | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

| I: | |||

| Gender (1 = M, 2 = F) | −.09 | … | … |

| Race (1 = European American, 2 = African American) | −.10 | … | … |

| Family income | −.15 | … | … |

| … | .022 | .022 | |

| II: | |||

| Perceived self-worth (teen report) | −.19+ | … | … |

| Maternal control (maternal report) | −.15 | … | … |

| Relationship with mother (teen report) | −.18+ | … | … |

| .159** | .137*** | ||

| III: Security | −.19+ | .182** | .023+ |

| IV: Preoccupation | .03 | .183** | .001 |

| V: | |||

| Security × control | −.18* | … | … |

| Preoccupation × control | −.27** | … | … |

| Preoccupation × income | −.20* | … | … |

| … | .298*** | .115*** | |

Note: β weights are those taken from entry of variables into models. N = 115.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p ≤ .01;

p < .001.

Figure 1.

Interaction of maternal control behaviors with attachment organization in predicting adolescent maternal reports of externalizing behaviors. Top, interaction of security with maternal control; bottom, interaction of preoccupation with maternal control. Variables are presented in standardized form.

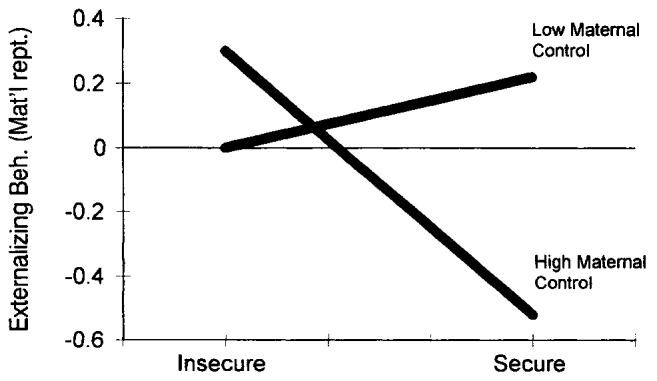

In predicting peer-reported delinquent behavior (see Table 6), both security and preoccupation added to prediction of delinquent behavior. Maternal control also interacted with security in this model. Examination of the security × control interaction (depicted in Figure 2) revealed that high maternal control was related to lower levels of peer-reported delinquency primarily for adolescents who displayed secure attachment organizations. For insecure adolescents, maternal control appeared relatively unrelated to adolescent deviance. Finally, family income and adolescent gender also interacted with preoccupation in predicting peer-reported delinquency. Examination of the income and gender interactions revealed that preoccupation was most strongly related to delinquency in low-income families and in males.

Table 6.

Hierarchical Regressions Predicting Peer-Reported Delinquent Behavior from Adolescent Attachment Organization after Accounting for Related Covariates

| Delinquent Behaviors (Peer Report) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| Predictors | β | R2 | ΔR2 |

| I: | |||

| Gender (1 = M, 2 = F) | −.18+ | … | … |

| Race (1 = European American, 2 = African American) | .03 | … | … |

| Family income | −.16 | … | … |

| … | .063 | .063 | |

| II: | |||

| Perceived self-worth (teen report) | −.07 | … | … |

| Maternal control (maternal report) | −.14 | … | … |

| Relationship with mother (teen report) | −.12 | … | … |

| … | .116+ | .053 | |

| III: Security | −.26* | .162* | .046* |

| IV: Preoccupation | .28* | .216** | .046* |

| V: | |||

| Security × control | −.24** | … | … |

| Preoccupation × income | −.24* | … | … |

| Preoccupation × gender | −.30** | … | … |

| … | .369*** | .153*** | |

Note: β weights are those taken from entry of variables into models. N = 98.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p ≤ .01;

p < .001.

Figure 2.

Interaction of maternal control behaviors with attachment organization in predicting peer reports of adolescents' delinquent behavior. Variables are presented in standardized form.

DISCUSSION

In this study, adolescent attachment organization was linked to a wide array of indices of adolescent psychosocial functioning. Security of attachment organization was linked in predicted directions to all four major indices of functioning examined after partialing the effects of gender, race/ethnicity, and family income. Adolescents who were relatively more able to talk about attachment experiences in ways that reflected balance, perspective, autonomy, and open acknowledgment of the importance of attachment were more likely to be socially accepted by peers and less likely to experience internalizing symptoms or to engage in externalizing and delinquent behaviors. These findings suggest a strikingly general and pervasive relation of attachment organization to different aspects of adolescent psychosocial functioning, particularly given that the four indices of functioning assessed were only modestly correlated with one another and in three of four cases were assessed by raters other than the adolescent.

After considering the direct relations of attachment organization to adaptive functioning, we went on to consider attachment as a predictor of functioning after accounting for several existing constructs that have been linked to adolescent functioning. Attachment organization added to variance in predicting each outcome even after accounting for these other predictors. In some cases, such as the prediction of social acceptance or peer-reported delinquency, inclusion of other predictors did not appreciably lessen the predictive value of attachment security. In other cases, such as the prediction of internalizing behaviors, the effect of some aspects of attachment organization (i.e., security but not preoccupation) disappeared after accounting for factors such as adolescents' perceived self-worth. This suggests not that insecurity is unrelated to internalizing behaviors but, rather, that the aspect of insecurity that was related to internalizing behaviors overlapped with an individual's low perceived self-worth. This is consistent with the idea that insecure attachment organizations may partly reflect internal models in which the self is viewed as unable, and perhaps unworthy, of getting attachment needs met from attachment figures (Bowlby, 1980).

Overall, these findings suggest that in adolescence, security in attachment organization is not simply a marker of positive models of oneself or one's relationship with parents, although it does overlap to some degree with such markers in predicting functioning. Rather, security is clearly linked to functioning via other mechanisms as well, perhaps because it reflects a capacity for internal organization of affect and cognition surrounding attachment experiences that has broad applicability to psychosocial functioning (Lay, Waters, Posada, & Ridgeway, 1995; Main, 1996). Notably, the adult attachment interview focuses only briefly upon qualities of current relationships, and its coding primarily assesses cognitive processes reflected in adolescents' discourse about affectively charged attachment experiences. It is the degree of overall coherence embodied in these processes that thus appears most likely to be broadly linked to psychosocial functioning.

Preoccupation with attachment experiences was found to be less broadly related to adolescent functioning but did contribute to explained variance in both adolescents' internalizing symptoms and in their externalizing and delinquent behavior. The relation of preoccupation to reported internalizing behaviors is suggestive of the ruminative styles of coping with stress that have been found predictive of depression in adolescence and beyond (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993). Both preoccupation and ruminative coping styles may reflect a pattern of repeated yet unproductive attention to (and expression of) internal signs of distress. Attachment theory suggests that these styles might be interpreted as attachment behaviors that implicitly seek comfort from others and become hyperactivated in some individuals (Allen et al., in press; Dozier & Lee, 1995; Kobak & Cole, 1994). Alternatively, high levels of internal distress might lead to difficulties in getting this distress assuaged by attachment figures, which in turn could lead to insecurity and preoccupation with attachment relationships.

The link between preoccupied attachment organization and peer-reported delinquency somewhat differs from prior findings that have associated externalizing behaviors with use of dismissing attachment strategies (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Alexander et al., 1989; Allen, Hauser, & Borman-Spurrell, 1996; Lay et al., 1989; Russo et al., 1981; Sroufe et al., 1984; Waters et al., 1979). One explanation is that a preoccupied attachment organization may so undermine progress in the critical developmental task of establishing autonomy with parents that adolescents may turn to delinquent behaviors either in frustration or in a desperate attempt to gain autonomy (Allen, Hauser, Eickholt, Bell, & O'Connor, 1994; Allen, Hauser, O'Connor, Bell, & Eickholt, 1996). Alternatively, externalizing behaviors may serve as a primitive call for help from attachment figures in adolescence and thus serve to heighten the intensity of the attachment relationship, albeit in a negative fashion (Allen & Hauser, 1996; Allen & Land, in press).

Although there were direct relations between security and adolescents' externalizing and delinquent behavior, these relations were strongest in adolescents who also displayed other demographic and behavioral risk factors for externalizing behavior, such as low family income. The interactions depicted in Figure 1 also suggest something more specific about the relation of maternal control to adolescent deviance. In both interactions, high maternal control was associated with lower levels of adolescent deviance primarily for adolescents who appeared open to thinking about attachment relationships, whether such openness appeared as secure valuing of attachment or as preoccupation with attachment. This suggests an important potential modification to theories about the importance of parental behavioral control techniques (Patterson et al., 1989). These techniques may be differentially effective depending upon the adolescents' orientation toward attachment experiences and may be truly effective only when adolescents are not dismissing of attachment. The interaction of attachment organization with maternal control strategies found in this study also suggests an explanation for why studies that have simply related attachment to externalizing behavior problems (without considering possible moderating effects of maternal control strategies) have yielded somewhat conflicting results (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Alexander et al., 1989; Lay et al., 1989; Russo et al., 1981; Sroufe et al., 1984; Waters et al., 1979).

Overall, these findings suggest that attachment organization is integrally linked to a broad array of distinct indicators of adolescent psychosocial functioning assessed by a variety of different reporters and methods. One explanation for this broad pattern of findings is that the capacity to process emotion and memories around attachment experiences is a fundamental developmental capacity in adolescence that is integrally linked (both directly, indirectly, and as a moderator) to numerous aspects of adolescent psychosocial functioning. This would mean that qualities of attachment organization, although initially derived from interactions with a specific caregiver, may become generalized to suffuse a wide array of social interactions by adolescence. Evidence of substantial continuity of attachment organization across the life span and across generations (Benoit & Parker, 1994; Waters et al., 1995) raises the possibility that attachment organization may serve as an important internal (yet observable) mediator of well-established long-term connections between problematic parent-child interactions and negative adolescent outcomes (Allen & Land, in press). If this premise is supported in future longitudinal and experimental research, then it also suggests cognitive mechanisms (i.e., incoherence, distortion of memories, and inability to think/speak clearly about attachment relationships) that may serve as potential points of intervention in breaking such links.

The cross-sectional nature of this study also leaves open several types of alternative explanations for its overall findings, including the possibility that poor functioning leads to insecure attachment organization or that other unmeasured factors are influencing both adolescent functioning and attachment organization. Emerging data about the relatively high degree of long-term and intergenerational continuity in patterns of attachment organization (Benoit & Parker, 1994; Waters et al., 1995) suggest that attachment organization may temporally precede some of the indices of psychosocial functioning examined. Although this temporal precedence leads us to prefer explanations based upon a causal role of attachment organization in functioning as outlined above, ultimately, these explanations are unprovable with the available data and must await further longitudinal and experimental research for either confirmation or disconfirmation.

In addition to its cross-sectional nature, a second limitation to these findings stems from the goal of the study to assess relations of attachment to indices of social functioning in a moderately at-risk sample, for whom differences in levels of psychosocial functioning were most likely to be truly meaningful. Whereas this sample is fairly easily identified (representing the “risky half” of a high school class academically) this does not mean that these findings would necessarily generalize to all adolescents in typical high school classes. Further, within the identified population, only about half of potentially eligible families chose to participate in the study. Although this is to be expected in a study requiring significant investments of family time, possible selection biases in who did and did not participate would further tend to limit generalizability of these data. Also, inclusion of data on fathers would have allowed further examination of the role of parental, not just maternal, relationships upon indices of functioning.

Limits to the attachment data themselves also suggest several areas where further research might be profitable. First, the nature of this sample precluded examination of dismissing attachment organizations as separate from insecurity generally, as these two were highly confounded. Also, the Q-sort methodology employed in this study, although empirically linked to classifications using the adult attachment interview classification system, did not allow assessment of insecure/unresolved classifications. This does not invalidate the present findings, as unresolved organization is a superordinate classification that coexists with an otherwise secure, dismissing, or preoccupied attachment organization, but it does suggest that future studies might explore the role of this additional aspect of attachment organization in adolescent functioning.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the Spencer and William T. Grant foundations. Write-up of this study was also funded by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health to the first author.

REFERENCES

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Youth Self-Report and 1991 Profile. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. The child behavior profile: II. Boys aged 12–16 and girls aged 6–11 and 12–16. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:223–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the child behavior checklist. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Behavioral problems and competencies reported by parents of normal and disturbed children aged four through sixteen. (Serial No. 188).Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1981;46(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist. 1989;44:709–716. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the Strange Situation. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Marvin RS. Waters E, Vaughn BE, Posada G, Kondo-Ikemura K, editors. On shaping of attachment theory and research: An interview with Mary D. S. Ainsworth (Fall 1994) (Serial No. 244).Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1995;60(2–3) Caregiving, cultural, and cognitive perspectives on secure-base behavior and working models. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JF, Waldron HB, Barton C, Mas CH. The minimizing of blaming attributions and behaviors in delinquent families. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;57:19–24. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST. Autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-family interactions as predictors of young adults' states of mind regarding attachment. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Borman-Spurrell E. Attachment insecurity and related sequelae of severe adolescent psychopathology: An eleven-year follow-up study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:254–263. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, Eickholt C, Bell KL, O'Connor TG. Autonomy and relatedness in family interactions as predictors of expressions of negative adolescent affect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:535–552. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Hauser ST, O'Connor TG, Bell KL, Eickholt C. The connection of observed hostile family conflict to adolescents' developing autonomy and relatedness with parents. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:425–442. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Kuperminc GP, Moore CM. Developmental approaches to understanding adolescent deviance. In: Luthar SS, Burack JA, Cicchetti D, Weisz J, editors. Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on risk and disorder. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Land D. Attachment in adolescence. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment theory and research. Guilford; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1987;16:427–454. doi: 10.1007/BF02202939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Effective parenting during the early adolescent transition. In: Cowan PA, Hetherington EM, editors. Family transitions: Advances in family research series. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D, Parker K. Stability and transmission of attachment across three generations. Child Development. 1994;65:1444–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ. Developmental changes in conformity to peers and parents. Developmental Psychology. 1979;15:608–616. [Google Scholar]

- Borman-Spurrell E, Allen JP, Hauser ST, Carter A, Cole-Detke HC. Assessing adult attachment: A comparison of interview-based and self-report methods. 1995 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. Basic Books; New York: 1980. Original work published 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: anxiety and anger. Basic Books; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss, sadness and depression. Basic Books; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J, Kirsch S, Scolton K, Parke RD. Attachment and representations of peer relationships. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:892–904. [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cohn DA, Cowan CP, Pearson JL. Parents' attachment histories and children's externalizing and internalizing behaviors: Exploring family systems models of linkage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:53–63. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell J, Feldman S. The effects of mothers' internal models of relations and children's developmental and behavioral status on mother-child interactions. Child Development. 1988;59:1273–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowell J, Treboux D, Waters E. Alternatives to the Adult Attachment Interview: Self-reports of attachment style and relationships with mothers and partners; Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development; New Orleans. 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Cicchetti D. Toward a transactional model of relations between attachment and depression. In: Greenberg MT, Cicchetti D, Cummings EM, editors. Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA. Social-cognitive mechanisms in the development of conduct disorder and depression. Annual Review of Psychology. 1993;44:559–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.44.020193.003015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozier M, Lee SW. Discrepancies between self- and other-report of psychiatric symptomatology: Effects of dismissing attachment strategies. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:217–226. [Google Scholar]

- Elicker J, Englund M, Sroufe LA. Predicting peer competence and peer relationships in childhood from early parent–child relationships. In: Parke RD, Ladd G, editors. Family-peer relationships: Modes of linkage. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1992. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin LA, Furman W. Adolescent girls' relationships with mothers and best friends. Child Development. 1996;67:375–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, Main M. Adult Attachment Interview. 3d ed. Department of Psychology, University of California; Berkeley: 1996. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson M, Hirschi T. A general theory of crime. Stanford University Press; Stanford, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Speltz ML. Attachment and the ontogeny of conduct problems. In: Belsky J, Nezworski T, editors. Clinical implications of attachment. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. pp. 177–218. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Adolescent Self-Perception Profile. Author; Denver: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington EM, Clingempeel WG. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. (Serial No. 227).Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1992;57(2–3):1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole C. Attachment and metamonitoring: Implications for adolescent autonomy and psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, editor. Rochester symposium on development and psychopathology: Vol. 5. Disorders of the self. Rochester University Press; Rochester, NY: 1994. pp. 267–297. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole HE, Ferenz-Gillies R, Fleming WS, Gamble W. Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem solving: A control theory analysis. Child Development. 1993;64:231–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Sceery A. Attachment in late adolescence: Working models, affect regulation and representations of self and others. Child Development. 1988;59:135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1988.tb03201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Sudler N, Gamble W. Attachment and depressive symptoms during adolescence: A developmental pathways analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Lay KL, Waters E, Park KA. Maternal responsiveness and child compliance: The role of mood as mediator. Child Development. 1989;60:1405–1411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lay K, Waters E, Posada G, Ridgeway D. Waters E, Vaughn BE, Posada G, Kondo-Ikemura K, editors. Attachment security, affect regulation, and defensive responses to mood induction. (Serial No. 244).Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1995;60(2–3) Caregiving, cultural, and cognitive perspectives on secure-base behavior and working models. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K. Attachment relationships among children with aggressive behavior problems: The role of disorganized early attachment patterns. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:64–73. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Introduction to the special section on attachment and psychopathology: 2. Overview of the field of attachment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:237–243. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Goldwyn R. Adult attachment rating and classification systems. In: Main M, editor. A typology of human attachment organization assessed in discourse, drawings and interviews (working title) Cambridge University Press; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. Effects of rumination and distraction on naturally occurring depressed mood. Cognition and Emotion. 1993;7:561–570. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Egeland B, Adam EK. Adult attachment classification and self-reported psychiatric symptomatology as assessed by the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:273–281. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstein DS, Horowitz HA. Adolescent attachment and psychopathology. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:244–253. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo DC, Cataldo MF, Cushing PJ. Compliance training and behavioral covariation in the treatment of multiple behavior problems. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:209–222. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slough NM, Greenberg MT. Five-year-olds' representations of separation from parents: Responses from the perspective of self and other. In: Bretherton I, Watson MW, editors. Children's perspectives on the family. Vol. 48. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1990. New Directions for Child Development. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Carlson E, Shulman S. Individuals in relationships: Development from infancy through adolescence. In: Funder D, Parke R, Tamlinson-Keasey C, Widaman K, editors. Studying lives through time. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1993. pp. 315–342. [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Schork E, Motti E, Lawroski N, LaFreniere P. The role of affect in emerging social competence. In: Izard C, Kagan J, Zajonc R, editors. Emotion, cognition and behavior. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1984. pp. 289–319. [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH. Adult attachment representations, parental responsiveness, and infant attachment: A meta-analysis on the predictive validity of the Adult Attachment Interview. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:387–403. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward MJ, Carlson EA. Associations among adult attachment representations, maternal sensitivity, and infant-mother attachment in a sample of adolescent mothers. Child Development. 1995;66:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Merrick SK, Albersheim LJ, Treboux D. Attachment security from infancy to early adulthood: A 20-year longitudinal study; Paper presented at the biennial conference of the Society for Research in Child Development; New Orleans. Mar, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Wippman J, Sroufe LA. Attachment, positive affect, and competence in the peer group: Two studies in construct validation. Child Development. 1979;50:821–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]