Short abstract

The NHS focus on memory clinics driven by drugs that slow cognitive decline is taking resources away from services offering long term integrated care. The role of these clinics needs reconsideration alongside availability of the drugs

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is approaching the end of a controversial consultation process on proposed radical revisions to its guidelines on drugs for dementia. Since 2001 the institute has recommended that the National Health Service in England and Wales should make the licensed cholinesterase inhibitors donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine available to people with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease.1

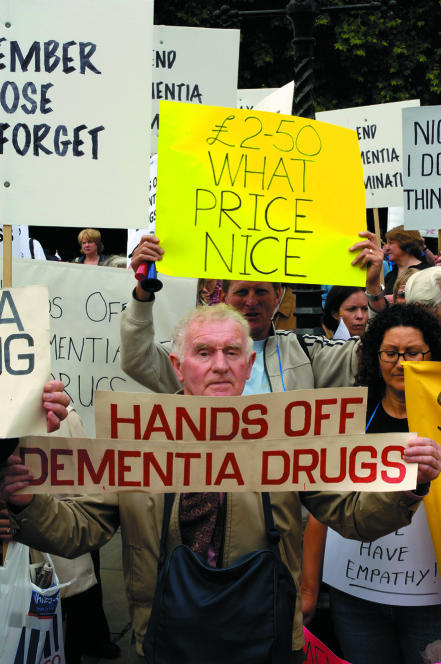

Figure 1.

NICE guidelines met a hostile reception

Credit: MARK THOMAS

The available research in 2001 could not provide guidance on which patients would respond to these drugs.2 However, when compared with placebo these drugs slowed cognitive decline. Over six months there was an average advantage of 2-3 points on the cognitive section of the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale, which has a range of 70 to 0. Rates of progression vary widely, but the expected average annual decline on this scale in placebo treated patients is 5-6 points.1,2 Outside trials the mean annual rate of change is about 8-9 points.3

Carers often report improvements in behavioural disturbances, neuropsychiatric symptoms, motivation, and activities of daily living when their relatives start taking cognitive enhancers but also when they are prescribed placebo. A combination of these features plus cognitive function influence clinicians' global ratings of change, which have usually favoured the active treatments in controlled trials.2

Unanswered questions

NICE and its main advisers acknowledged shortcomings in their and others' economic analyses. Calculation of quality adjusted life years (QALYs) has been based on cross sectional data from carers of patients with Alzheimer's disease using the health utility index, which was not designed for use in dementia.4 A major influence on costs is the duration from onset until full time nursing care is required. However, this is crucially influenced by characteristics of the care givers, as well as patients' cognitive functioning, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and functional abilities and social, cultural, financial, and health service issues.5,6 The randomised trials did not directly examine whether cholinesterase inhibitors delayed placement in care homes, but this was assumed on the basis of evidence of a slow down in cognitive decline.2

NICE stressed that further research was required—not just drug trials but also examination of other key interventions such as home support and rehabilitation. It flagged up the need for improved measures of outcome that were meaningful to patients, carers, and policy makers, and it planned to revisit its recommendations after several years.1,2

Effect on psychiatric services

The guidelines were welcomed by patient and carer organisations and led to optimism among some clinicians.7 They may have contributed to earlier referral of patients with memory impairment to secondary care services.8 Another consequence has been a large increase in the number of specialist memory clinics.9,10

Memory clinics had been established in teaching hospitals during the previous three decades. Their model of service provision has been solely office based, even though this was not previously a major component of old age psychiatry.11,12 The clinics are multidisciplinary, with input from psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, psychiatric nurses, and sometimes occupational therapists, speech therapists, geriatricians, and neurologists.9,13,14 The clinics' aims were to establish specialist centres for the diagnosis of dementia and for refining the methods of diagnosis; to give advice and counselling to patients and carers; and to provide post-graduate education. Their main aim has been to facilitate recruitment of patients for aetiological research and randomised controlled trials.9,13,14

Early exponents of memory clinics can be criticised for not being clear in their own minds whether they were running projects or contributing to regional health services. However, when the centres were confined to a few academic centres of excellence they did not adversely influence (and, indeed, could help inform) the hospital and community care of people with dementia. Unfortunately, this service model has been widely adopted in the wake of the introduction of cholinesterase inhibitors, sometimes with funding from the drug manufacturers.9,15

Problems of memory clinics

Widespread clinics have distorted clinical priorities. Memory clinics have recruited full multidisciplinary teams while there is a shortage of mental health professionals throughout the United Kingdom. Their patients are routinely given intensely detailed neuropsychological assessments, even though the findings seldom influence clinical decisions. In some clinics a consultant geriatrician evaluates every patient, often identifying problems such as vascular disease, drug side effects, and vitamin deficiencies.13,14 Detection of such problems is part of the day to day work of old age psychiatrists, who refer to physicians and neurologists only when their diagnostic and therapeutic skills are genuinely required. The clinical activity of some memory clinic nurses is explicitly based on ensuring adherence to NICE's prescribing guidelines.16 They spend their time monitoring the decline of patients taking cholinesterase inhibitors rather than ensuring the delivery of multidisciplinary care plans.

Specialist memory clinics do not offer care in the community to their patients as they decline.9,14 This means that the clinics are confining themselves to the easy parts of the management of neurodegenerative disorders. Patients are assessed and then discharged or else reviewed until cognitive deterioration and behavioural disturbances become problematic. They are then referred to ordinary old age psychiatry teams, which have to arrange proper management plans; this sometimes involves undoing what has been done by clinicians who lack experience with long term care of people with dementia. The task is not made easier when potential members of the multidisciplinary team have been recruited to memory clinics.

Draft revised guidelines

Further research is now available to policy makers.17-21 The meta-analyses show quite consistently that these medicines have modest beneficial effects compared with placebo. For example, studies show a significant weighted mean difference of 2-3 points at six months on the Alzheimer's disease assessment scale,17-21 a weighted mean advantage of 2.4 points (P < 0.0001) in assessment of activities of daily living on the progressive deterioration scale (range 0-100),21 and weighted mean difference of about 2.5 points at six months (P = 0.004) on the neuropsychiatric inventory (range 12-120).20,21

The findings on efficacy are relatively uncontroversial compared with the health economic analyses. The important work of Neumann and colleagues on health utilities in dementia4 has not been sufficiently developed, but assumptions about these make crucial differences when modelling costs per QALY gained.

Extrapolations from improved cognitive test scores to delays in care home placement are still being made. A multicentre trial in the United Kingdom that chose placement in care homes as a primary outcome found that 9% of the donepezil group and 14% of patients receiving placebo had been admitted to care homes within one year—a potentially clinically important but not statistically significant difference. After three years the figures in the two groups were almost identical (42% v 44%).w1 NICE has given substantial weight to this trial, although its findings are disputed on several grounds including the use of drug washout periods that may have lessened efficacy and are not used in clinical practice.w2 Observational studies making ambitious claims for cholinesterase inhibitors in delaying admission to care homes have been cited, but these are unhelpful because of their (often obvious and severe) methodological flaws.w3-w5

A draft of revised guidelines released in March 2005 concluded that the NHS should no longer prescribe cholinesterase inhibitors because they do not provide value for money.w6 This led to almost uniformly hostile reactions from clinicians, patients, and carers and their representative organisations with support from the lay media. NICE received over 7000 responses, and concerns were voiced by politicians inside and outside government.w7

The appraisal committee revisited their proposals in the light of the consultation process and after subgroup analyses that seem to stretch NICE's methods to breaking point.w8 These analyses suggested a differential advantage for more severely affected patients. In mild Alzheimer's disease the best estimate of cost per QALY ranged from £56 000 to £72 000 (€83 000-€107 000, $106 000-$137 000). At a moderately severe stage the best estimate was £23 000 to £35 000.w9 The committee could not reach a consensus and had a ballot on whether it should stick with the view that these medicines should no longer be used at all or whether they should be recommended for only moderate Alzheimer's disease.w10 Restricted use was favoured by 16 votes to 12. Draft proposals to this effect have been through yet another acrimonious consultation process,w11 and the results of formal appeals are awaited. There are widespread clinical concerns about these latest recommendations, not least because it will be extremely difficult (perhaps impossible) to wait for a diagnosed patient to deteriorate before starting treatment.

Summary points

The appropriate use of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease is controversial

Most of the controversy arises because their effects are, by any criteria, modest

Memory clinics have been established for the prescription and monitoring of these medicines

These clinics are diverting resources from high quality integrated care

Better care

The scientific debate has been accompanied by moving accounts from carers of marked improvements in their affected relatives after starting treatment and dismay that a source of hope is being taken away. NICE has been unfairly accused of ageism and stigmatisation of people with dementia.w7 w12 A frequent argument is that the new recommendations are wrong because “the medicines are all that doctors have to offer.”w13 This argument is unacceptable. Modern dementia health care involves working with patients and relatives from referral (which can sometimes predate a diagnosis by years) through to death. There should be continuity of care from a multidisciplinary team working with general practitioners, the local social work department, and other care providers. It should aspire to early intervention and, when required, assistance during crises and assertive outreach.

When full time nursing becomes necessary, the local old age psychiatry service should continue to provide support to patients and to care home staff. Any prescribing, monitoring, and discontinuation of cholinesterase inhibitors should be carried out within such a service framework. The evidence based interventions that should be provided by properly organised multidisciplinary services are well known to old age psychiatrists and have recently been outlined in a draft document commissioned by NICE and its sister organisation the Social Care Institute for Excellence.w14

It has been claimed that adoption of the revised guidelines would be devastating for patients and carers. The tragedy is not the proposed restrictions, but the fact that the only currently licensed medicines for a cruel illness have turned out to be of marginal benefit—from statistical, clinical, and public health viewpoints. This is the main reason for the prolonged and tortuous debate on their appropriate use. Whatever the final outcome of NICE's deliberations, the human and financial resources that have become tied up in clinics organised around prescription of cholinesterase inhibitors must be diverted to old age psychiatry teams and their social care counterparts. These medicines should no longer be allowed to have such influence on services for patients with Alzheimer's disease and their families.

Supplementary Material

References w1-w14 are on bmj.com

References w1-w14 are on bmj.com

We thank the referees for their helpful comments on an earlier draft.

Contributors and sources: GAJ, SVM, and AJP all have a particular interest in delivery of psychiatry services. This article is the end product of several years' discussion on this topic, and experience of dealing with patients with dementia within their services. All authors contributed to the ideas for this paper and to its writing and redrafting. AJP is the guarantor.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Technology appraisal guidance number 19. Donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. London: NICE, 2001.

- 2.Clegg A, Bryant J, Nicholson T, McIntyre L, De Broe S, Gerard K, et al. Clinical and cost effectiveness of donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine for Alzheimer's disease: a rapid and systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2001;5(1). 1-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corey-Bloom J, Fleisher AS. The natural history of Alzheimer's disease. In: Burns A, O'Brien J, Ames D, eds. Dementia. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005: 376-86.

- 4.Neumann PJ, Kuntz KM, Leon J, Araki SS, Hermann RC, Hsu MA, et al. Health utilities in Alzheimer's disease: a cross-sectional study of patients and caregivers. Med Care 1999;37: 27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeo G, Gallagher-Thompson D, eds. Ethnicity and the dementias. Washington, DC: Taylor and Francis, 1996.

- 6.Yaffe K, Newcomer R, Lindquist K, Covinsky KE. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA 2002;287: 2090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O'Brien JT, Ballard CG. Drugs for Alzheimer's disease. Cholinesterase inhibitors have passed NICE's hurdle. BMJ 2001;323: 123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Loughlin C, Darley J. Has the referral of older adults with dementia changed since the availability of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and the NICE guidelines? Psychiatric Bull 2006;30: 131-4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker Z, Butler R. The memory clinic guide. London: Martin Dunitz, 2001.

- 10.Hope J. Memory clinics face axe due to drug ban. Daily Mail 2005. March 10.

- 11.Levy R, Post F, eds. The psychiatry of late life. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1982.

- 12.Dening T. Community psychiatry of old age: a UK perspective. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 1992;7: 757-66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson P, Inglis F, Findlay D, Gilchrist J, McMurdo MET. Memory clinic attenders: a review of 150 consecutive patients. Aging Mental Health 1997;1: 181-3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilcock GK, Bucks RS, Rockwood K. Diagnosis and management of dementia. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- 15.Boseley S. Lodged in the memory. Guardian 2002. November 25.

- 16.Sheehan B, Saad K. Service innovations: a dedicated drug treatment service for dementia. Psychiatr Bull 2006;30: 146-8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loveman E, Green C, Kirby J, Takeda A, Picot J, Payne E, et al. The clinical and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine, and memantine for Alzheimer's disease. Health Technol Assess 2006;10(1): 1-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birks J, Harvey RJ. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD001190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Birks J, Grimley Evans J, Iakovidou V, Tsolaki M. Rivastigmine for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(4):CD001191. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Loy C, Schneider L. Galantamine for Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD001747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;(1):CD005593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.