Abstract

As reported previously (J. R. Jarvest et al., J. Med. Chem. 45:1952-1962, 2002), potent inhibitors (at nanomolar concentrations) of Staphylococcus aureus methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MetS; encoded by metS1) have been derived from a high-throughput screening assay hit. Optimized compounds showed excellent activities against staphylococcal and enterococcal pathogens. We report on the bimodal susceptibilities of S. pneumoniae strains, a significant fraction of which was found to be resistant (MIC, ≥8 mg/liter) to these inhibitors. Using molecular genetic techniques, we have found that the mechanism of resistance is the presence of a second, distantly related MetS enzyme, MetS2, encoded by metS2. We present evidence that the metS2 gene is necessary and sufficient for resistance to MetS inhibitors. PCR analysis for the presence of metS2 among a large sample (n = 315) of S. pneumoniae isolates revealed that it is widespread geographically and chronologically, occurring at a frequency of about 46%. All isolates tested also contained the metS1 gene. Searches of public sequence databases revealed that S. pneumoniae MetS2 was most similar to MetS in Bacillus anthracis, followed by MetS in various non-gram-positive bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic species, with streptococcal MetS being considerably less similar. We propose that the presence of metS2 in specific strains of S. pneumoniae is the result of horizontal gene transfer which has been driven by selection for resistance to some unknown class of naturally occurring antibiotics with similarities to recently reported synthetic MetS inhibitors.

The development of antimicrobial compounds with novel modes of action is critical to the treatment of bacterial infections, which are increasingly showing broad resistance to the available agents used for therapy. Particularly promising bacterial targets are the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (13), which serve in protein synthesis for the attachment of an amino acid to its cognate tRNA. The natural product compound mupirocin (pseudomonic acid) is a specific inhibitor of bacterial isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase (6) and is used as a topical antibiotic against Staphylococcus aureus infections (15).

In our search for novel antibiotics effective against gram-positive coccal bacteria, we have undertaken high-throughput screening of small-molecule libraries for inhibitors of each aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase from S. aureus. We recently reported on a potent series of inhibitors of methionyl-tRNA synthetase (MetS; encoded by the gene metS) (11). This series of compounds exhibited activity against whole cells of a variety of gram-positive bacteria. Additionally, one compound was active in animal models. Whole-cell activity was shown by both physiological and genetic techniques to be due to MetS inhibition.

Although the MetS inhibitors are potent against a large number of strains of S. aureus and Enterococcus sp. isolates, the MICs of the MetS inhibitors for Streptococcus pneumoniae, as reported here, exhibited a broad distribution. We found that the MICs of a given compound could vary from 0.5 to >64 μg/ml for otherwise antibiotic-susceptible strains. Heterogeneous activity against strains of an important human pathogen such as S. pneumoniae is not a desirable trait for an antibiotic, so we embarked on a study to determine the cause of resistance. Here we show that resistance is due to the presence of a second MetS enzyme, MetS2, which is resistant to the compounds active against MetS1 and whose gene is widespread among clinical isolates of S. pneumoniae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, media, and growth conditions.

The S. pneumoniae strains used in the study described in this report were R6 (a commonly used laboratory strain), QA1442, and their derivatives. S. pneumoniae QA1442 was chosen for this study not only because of its resistance to MetS inhibitors but also because it is highly transformable. QA1442 is a member of the set of 40 strains originally tested for their sensitivities to MetS inhibitors. This set is from our Microbiology departmental strain collection and is used for routine profiling of antimicrobial compounds. Also used, where indicated, were clinical isolates collected as part of the Alexander Project, a global surveillance program for the monitoring of antibacterial resistance in key respiratory pathogens (5). S. pneumoniae was routinely propagated in THY medium (Todd-Hewitt medium supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract) at 37°C. MICs were determined by the broth microdilution method (11).

Isolation of SB-362916-sensitive mutants.

Strain QA1442 was mutagenized with 2% ethyl methanesulfonate. Mutagenized samples were subjected to three rounds of penicillin enrichment, as follows. Exponentially growing cells at an A600 of about 0.3 were treated with SB-362916 at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, followed 30 min later by treatment with penicillin G at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml. After 2 to 4 h of treatment, the penicillin G was removed by extensive washing and a second round of enrichment was commenced. Alternatively, samples of enriched cultures were frozen at −80°C in the presence of 10% glycerol and regrown for further enrichment. Survivors were plated on Trypticase soy agar-5% sheep blood agar plates, and the colonies were scored by their ability to grow in THY medium containing 10 μg of SB-362916 per ml. After three rounds of enrichment, approximately 20% of the survivors were sensitive to SB-362916. Two isolates, named QS1 and QS2, were further used in this study.

Transformation of S. pneumoniae.

A total of 106 S. pneumoniae R6 competent cells were incubated with DNA at 30°C for 30 min in the presence of 1 mg of competence-stimulating heptadecapeptide per ml by published methods (8) and transferred to 37°C for 90 min to allow expression of antibiotic resistance. The transformation mixtures were plated onto AGCH agar (12) containing antibiotic and were incubated at 37°C for 36 h under 5% CO2.

Preparation of an enriched genomic library.

Samples of genomic DNA digested to completion with different restriction enzymes were tested for their abilities to confer resistance to sensitive isolate QS1. It was found that HindIII-digested DNA was capable of transforming a sensitive strain, indicating that the target gene and sufficient flanking sequences for recombination lacked a HindIII restriction site. HindIII-digested DNA was then fractionated by sucrose density centrifugation, and fractions were tested for their abilities to transform QS1 to SB-362916 resistance. A fraction of HindIII-digested genomic DNA that conferred resistance (size range, 2 to 8 kb) was used to construct an enriched library in S. pneumoniae-Escherichia coli shuttle vector pDL278 (12a). Strain QS1 was then transformed with this library. The transformation mixture was plated onto medium containing either 25 or 40 μg of SB-362916 per ml (6 and 10 times the MIC, respectively).

Generation of S. pneumoniae metS allelic replacement mutants.

Chromosomal DNA fragments (500 bp) flanking the genes of interest were amplified from S. pneumoniae QA1442 chromosomal DNA by PCR. Primers were designed so that flanking genes and potential promoters would remain intact in the deletion mutant to minimize polar effects. The fragments were used to make allelic replacement constructs in which they flanked the erythromycin resistance gene (ermAM) from pAMβ1 or the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene from pC194. S. pneumoniae QA1442 competent cells were prepared and transformed in the presence of 1 mg of competence-stimulating heptadecapeptide per ml by published methods (8).

To generate allelic replacement mutants, a total of 106 S. pneumoniae QA1442 competent cells were incubated with 500 ng of the allelic replacement construct at 30°C for 30 min and transferred to 37°C for 90 min to allow expression of antibiotic resistance. The transformation mixtures were plated in AGCH agar (12) containing 1 μg of erythromycin per ml or 2.5 μg chloramphenicol per ml and were incubated at 37°C for 36 h under 5% CO2. Chromosomal DNA was prepared from the metS1 deletion mutants and was used to transform S. pneumoniae QA1442, from which metS2 was deleted, in the presence of 1 mg of competence-stimulating heptadecapeptide per ml. Similarly, DNA from the metS2 deletion mutant was used to transform the metS1 null strain. If no transformants were obtained in three separate transformation experiments with positive allelic replacement and transformation controls, the target gene was considered to be essential in vitro under the conditions chosen. Antibiotic-resistant S. pneumoniae colonies were picked and grown overnight in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco) supplemented with 5% (wt/vol) yeast extract.

Chromosomal DNA from putative S. pneumoniae allelic replacement mutants was examined by both Southern blotting and diagnostic PCR analyses to verify that the appropriate chromosomal DNA rearrangement had occurred. By the former method, flanking DNA fragments labeled by using the enhanced chemiluminescence random-prime labeling kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) were used as probes for chromosomal DNA restricted with appropriate enzymes and blotted by standard methods (14). By the latter method, DNA primers designed to hybridize within the antibiotic resistance determinant were paired with primers hybridizing to distal chromosomal sequences to generate DNA amplification products of characteristic sizes. DNA fragments were directly sequenced in both directions by using 3100 or 3700 automated sequencers (Applied Biosystems).

Sequence analysis.

We found other methionyl-tRNA synthetase sequences in public databases, including partial genome sequences (National Center for Biotechnology Information), using S. pneumoniae MetS2 as the query sequence. Searches for both translated open reading frames and complete DNA sequences were conducted by using the programs BLASTP and TBLASTN, respectively (1). Preliminary sequence data for Bacillus anthracis (Ames strain) were obtained from The Institute for Genomic Research through its website (http://www.tigr.org). The sequences were initially aligned by using the CLUSTALW program (version 1.8) (2) and were then manually refined by using the SEQLAB program of the GCG package (version 10.2; Genetics Computer Group, Madison Wis.). Sequence comparisons are based on the BLOSUM62 weighting matrix and the lengths of the shorter sequence without gaps.

Identification of metS2 among clinical isolates.

S. pneumoniae isolates were obtained from the collections of the Alexander Project (5). The earliest (1992) to the most recent (1999) isolates (n = 315) available from a wide geographical range were selected. Detection of the two loci in different strains was done by separate amplification reactions by PCRs with primers specific for metS1 (primer metS1F [5′-CATATCGGTTCTGCCTACACAACTAT-3′] and primer metS1R[5′-CTCGATGAAGTTGCGTAGCATTTCATT-3′]) and metS2 (primermetS2F [5′-GCAAACGGTTCGTTACATATTGGTCA-3′] and primer metS2R [5′-CTCAGGAGCATTTATTGTTAGGAAGTA-3′]), which amplified DNA fragments of 565 and 1,054 kb, respectively. Colonies on blood agar were transferred directly to PCR mixtures (PCR SuperMix High Fidelity; Gibco-BRL), which were set up according to the conditions recommended by the vendor. An initial cycle of 3 min of 94°C was followed by 35 cycles of 30 s of 94°C, 45 s of 50°C, and 1 min of 72°C, with a final cycle of 2 min of 72°C. All experiments were run in duplicate with positive and negative amplification controls. Following electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel, the gels were evaluated for the presence or absence of DNA fragments of the proper length. DNA fragments from 10 randomly selected experiments were sequenced to confirm that the metS1 and metS2 genes were the proper amplification products.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The S. pneumoniae metS2 gene is available from GenBank under accession number AY198311.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

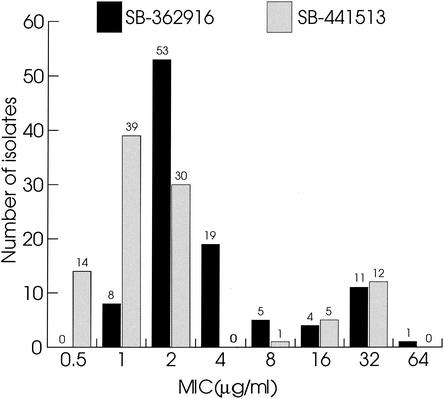

In our initial survey, 11 of 40 S. pneunomiae isolates were significantly more resistant to a class of synthetic MetS inhibitors (MICs, 8 μg/ml or higher). An extended profile was initiated to get a better indication of the distribution of the MICs. Of 101 clinical isolates recently collected from different clinics worldwide, about 20% were resistant to MetS inhibitors (as defined by MICs ≥8 μg/ml) (Fig. 1). Resistance to antimicrobial compounds is frequently due to target-based mutations. However, analysis of the sequences of the metS1 genes from a number of resistant isolates failed to reveal any consistent differences from those of the metS1 genes of sensitive strains (data not shown), making a target-based mechanism of resistance unlikely. For those strains the profiles of resistance to known antibiotics were not correlated with resistance to MetS inhibitors, which led us to conclude that the observed MICs were not the result of some multidrug resistance mechanism. These findings strongly suggested that the resistance mechanism was novel and unique to MetS inhibitors. A genetic approach was therefore undertaken to identify it.

FIG. 1.

Distribution of resistance in 101 S. pneunomiae isolates to three synthetic small-molecule inhibitors of MetS. Resistance to MetS inhibitors SB-362916, SB-430537, and SB-441513 is measured as the MIC. The absolute numbers of isolates are shown above each bar.

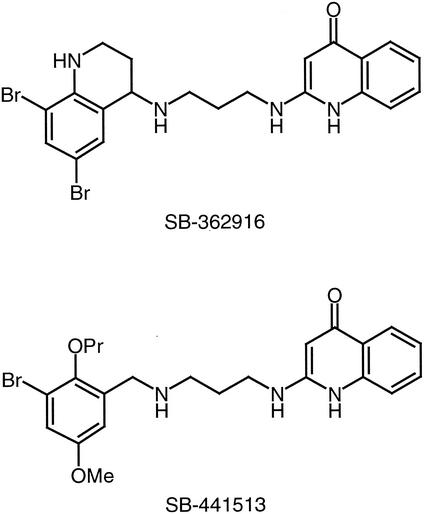

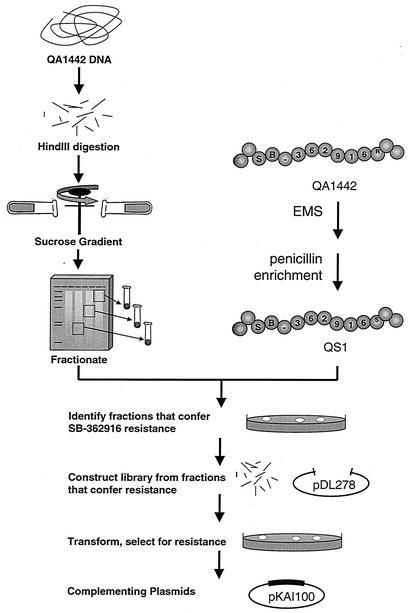

The strategy that we devised to identify the gene or genes required for resistance is based on the genetic transformation of a sensitive strain to resistance with DNA isolated from a resistant strain. Compound SB-362916 (Fig. 2), typical of the class of MetS inhibitors derived from the high-throughput screening effort, was used throughout this study. First attempts at transformation of sensitive strain R6 with genomic DNA from a resistant strain failed. This raised the possibility that the resistance determinant was part of an island of DNA not found in the genome of the sensitive strain; thus, DNA fragments with resistance factors could not recombine with the genome of the sensitive host. To address this, we isolated SB-362916-sensitive mutants of the normally resistant strain S. pneumoniae QA1442. The MICs for eight SB-362916-sensitive isolates were 4 μg/ml, whereas the MIC for the parent strain was 128 μg/ml. One of these sensitive isolates, QS1, was selected for further studies. Genomic DNA from QA1442 was capable of transforming QS1 to resistance, suggesting that the determinant is carried on a single locus (or on multiple tightly linked loci). To identify the allele responsible, an enriched library was constructed as described in Materials and Methods and was used to isolate clones capable of conferring SB-362916 resistance to QS1 (the scheme used to identify the resistance locus is outlined in Fig. 3). Screening of eight SB-362916-resistant colonies revealed that the sizes of the plasmid inserts were 1.5 to 4 kb. Five of the recombinant plasmids containing approximately 3-kb inserts were selected and used to transform S. pneumoniae R6. Of the clones tested, four were capable of transforming laboratory strain S. pneumoniae R6 to SB-362916 resistance. Sequence analysis of two of the plasmids that conferred SB-362916 resistance showed that they contained identical HindIII fragments. Further analysis of the 3-kb insert showed that it contained only one complete open reading frame, which encodes a novel MetS protein. To distinguish the two enzyme-encoding genes and their products, the previously identified gene is defined as metS1 and encodes MetS1. The second gene is designated metS2 and encodes the putative drug-resistant synthetase MetS2 (see below).

FIG. 2.

Structures of SB-362916 and SB-441513. Me, methyl; Pr, propyl.

FIG. 3.

Scheme used to identify the resistance locus. EMS, ethyl methanesulfonate

To confirm that the metS2 gene encodes an enzyme (MetS2) resistant to SB-362916, we constructed deletion mutants of strain S. pneumoniae QA1442 from which both metS1 and metS2 were deleted by allelic replacement. The ability to isolate deletion mutants from which each gene by itself is deleted indicates that both genes are functional and can complement each other, and consequently, neither gene is essential for viability in this strain background. A double-deletion mutant could not be generated, consistent with the expectation that no other source of MetS activity is present. We could not isolate a metS1 deletion mutant in laboratory strain S. pneumoniae R6, strongly suggesting that metS1 is essential in strains in which metS2 is lacking.

MIC analysis was performed with the QA1442 metS1 and metS2 deletion mutants. As shown in Table 1, deletion of metS2 completely abolished resistance to SB-362916, while deletion of metS1 had no effect on the MIC. We also sequenced metS2 from strains QS1 and QS2, sensitive variants of QA1442, and found alterations in one of two highly conserved residues, R35H and P487S. Taken together with the observed MICs of SB-362916 for these two sensitive mutants, which were identical to the MIC for the metS2 deletion mutant, we conclude that these mutants are likely metS2 null strains. Further evidence that MetS2 is responsible for the observed resistance is the finding that the recombinant MetS2 enzyme is resistant to MetS1 inhibitors in vitro (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

MICs of various compounds for S. pneumoniae QA1442 and its mutants

| Strain | MIC (μg/ml)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SB-362916 | Tetracycline | Chloramphenicola | Erythromycin | |

| QA1442 | >64 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.125 |

| QA1442 ΔmetS1 | >64 | 0.5 | 4 | >64 |

| QA1442 ΔmetS2 | 4 | 0.5 | 32 | 0.125 |

| QA1442 QS1 | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.125 |

| QA1442 QS2 | 4 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.125 |

The increased MICs of erythromycin and chloramphenicol for QA1442 ΔmetS1 and QA1442 ΔmetS2, respectively, are due to the resistance cassette used for gene disruption.

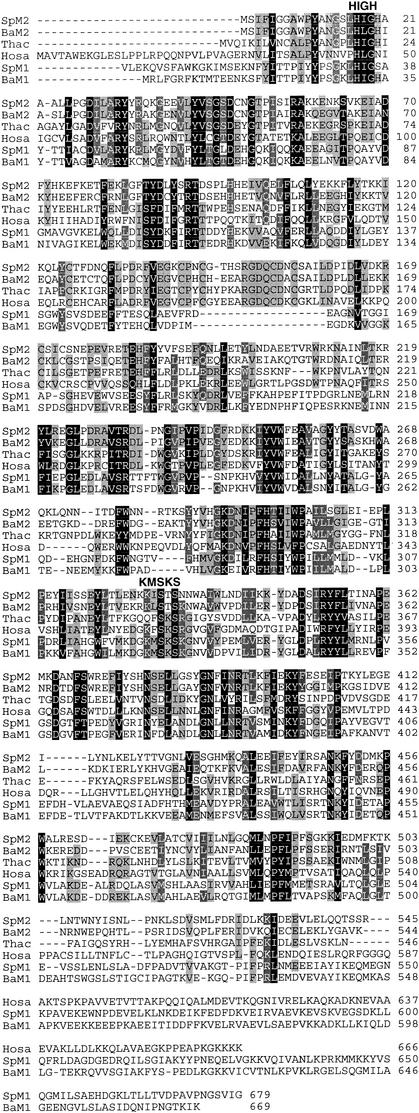

The amino acid sequence of S. pneumoniae MetS2 is highly distinctive from those of the MetS1 proteins typically found in S. pneumoniae and other gram-positive bacteria (Fig. 3). Searches of public sequence databases for sequences homologous with the MetS2 sequence revealed that the closest homologs to MetS2 were MetS from members of the domain Archaea, eukaryotes, and non-gram-positive bacteria such as Chlamydia and spirochetes, with one exception. Interestingly, B. anthracis has a MetS2 protein that was similar (65%) to that of S. pneumoniae. In addition to various amino acid substitutions, all MetS2-type proteins, including those of B. anthracis and S. pneumoniae, differ from MetS1-type proteins by having an inserted sequence of 17 or 18 amino acids between residues F173 and N192 of the human MetS protein (Fig. 4). Furthermore, B. anthracis has a second, more typical metS1 locus which is similar to those found in other Bacillus species as well as S. pneumoniae metS1. A comparison of the amino acid sequence similarities suggests that metS2 did not arise from a recent gene duplication event after the speciation of S. pneumoniae. We suggest that metS2 was probably acquired by S. pneumoniae from a distantly related species via horizontal gene transfer. A more extensive evolutionary analysis of MetS will be presented elsewhere.

FIG. 4.

Multiple-sequence alignment of MetS. The sequences shown are those of S. pneumoniae MetS1 (SpM1) and MetS2 (SpM2) and examples of closely related orthologs in public genome databases, B. anthracis MetS1 (BaM1) and MetS2 (BaM2), Thermoplasma acidophilum (Thac), a member of the domain Archaea, and Homo sapiens (Hosa). The locations of the conserved amino acid motifs HIGH and KMSKS, which are signatures for class I aminoacyl-tRNA, are indicated above the sequences. The dark, medium, and light shadings represent high (100%), medium (80%), and low (60%) levels of amino acid conservation, respectively. The figure was prepared with GeneDoc software (version 2.6002; K. B. Nicholas and H. B. Nicholas, Jr., 2000 [distributed by the authors at www.psu.edu/biomed/genedoc]).

Database searches failed to reveal other examples of metS2 in gram-positive coccal species; thus, we assume that this locus is specific to particular S. pneumoniae strains. In order to evaluate the global distribution of metS2, we surveyed 315 clinical S. pneumoniae isolates collected as part of the Alexander Project surveillance program for the occurrence of metS1 and metS2 using PCR with specific DNA primer pairs. These isolates were obtained from various clinics in seven different countries between 1992 and 1998. We found the metS2 locus to be very widespread in terms of both geography and time (Table 2), being detected in 46% of all isolates tested. Insufficient sample size is the likely explanation for the few missing occurrences of metS2 in particular country and year combinations.

TABLE 2.

Occurrence of metS2 loci in S. pneumoniae clinical isolates

| Country | Yr of isolation | No. of isolates in which metS2 isa:

|

Frequency of metS2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | Total | |||

| France | 1992 | 3 | 8 | 11 | 0.27 |

| 1993 | 9 | 11 | 20 | 0.45 | |

| 1994 | 7 | 7 | 14 | 0.50 | |

| 1995 | 9 | 4 | 13 | 0.69 | |

| 1996 | 7 | 6 | 13 | 0.54 | |

| 1997 | 6 | 9 | 15 | 0.40 | |

| 1998 | 4 | 11 | 15 | 0.27 | |

| Germany | 1992 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0.25 |

| 1994 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0.00 | |

| 1997 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.67 | |

| 1998 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 0.17 | |

| Italy | 1994 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0.50 |

| 1995 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 0.60 | |

| 1996 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 0.30 | |

| 1997 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0.43 | |

| 1998 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0.00 | |

| Spain | 1992 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 0.40 |

| 1993 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 0.43 | |

| 1994 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 0.86 | |

| 1995 | 9 | 1 | 10 | 0.90 | |

| 1996 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0.80 | |

| 1997 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 0.75 | |

| United Kingdom | 1992 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0.50 |

| 1993 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 0.13 | |

| 1994 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0.33 | |

| 1995 | 10 | 2 | 12 | 0.83 | |

| 1996 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 0.75 | |

| 1997 | 7 | 3 | 10 | 0.70 | |

| 1998 | 21 | 38 | 59 | 0.36 | |

| United States | 1992 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0.00 |

| 1997 | 7 | 10 | 17 | 0.41 | |

| Hong Kong | 1997 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0.00 |

| Total | 144 | 171 | 315 | 0.46 | |

The isolates were evaluated for the presence or absence of metS2 by PCR amplification experiments.

The rate of occurrence of metS2, as determined by PCR, in clinical isolates is higher (46%) than that which would be predicted from MIC data collected in earlier studies (20%). Larger sample sizes might result in more consistent results between the two methods. Also, there could be variability with respect to resistance to MetS inhibitors among metS2 gene products, or metS2 may not be expressed in all strains that possess it. More extensive MIC profiling and PCR surveys would be required to test these alternative hypotheses.

All Alexander Project isolates have been tested for resistance to at least 15 commercially available antibiotics (5). We did not find any trend in the occurrence of metS2 and resistance or susceptibility to existing classes of antibiotics. Therefore, metS2 does not appear to be associated with known mechanisms of drug resistance or temporal or geographical segregation. Interestingly, the typical metS1 locus was found in all isolates surveyed, which supports the hypothesis that metS1 was present in the ancestor of S. pneumoniae, while metS2 was horizontally transferred into specific S. pneumoniae strains.

Dual copies of a few types of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases have been reported for some bacteria, such as tyrosyl-, threonyl-, and histidyl-tRNA synthetases in the gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis, all of which are duplications within the domain Bacteria and were not acquired by horizontal transfer from an archaebacterium or eukaryote (for reviews, see references 2 and 17). An exception is the acquisition of plasmids with eukaryote-like isoleucyl-tRNA synthetases by certain strains of S. aureus (3). Similar to MetS, this divergent isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase conveys resistance to an antibiotic, pseudomonic acid (mupirocin), which is the derivative of a natural product (4, 7, 9). However, unlike mupirocin, recently developed MetS inhibitors are totally synthetic compounds and do not resemble any known classes of natural antibiotics (11). Thus, bacteria have never been exposed to these compounds in either clinical or natural environments. The widespread occurrence of the metS2 gene suggests that it must contribute some selective advantage to those strains harboring it. It is therefore possible that MetS is inhibited by some unknown class of natural product antibiotics and that S. pnuemoniae acquired metS2 as a countermeasure to such compounds.

Our study shows the great importance of understanding intraspecific genomic variation in pathogenic bacteria. Although the complete genome sequences of two different S. pneumoniae strains are available, neither had MetS2 or any indication of duplicate aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (10, 16). As witnessed here, a large number of S. pneumoniae strains are capable of incorporating genes from diverse exogenous species. This gene incorporation introduces considerable intraspecific genetic variation and, potentially, seemingly novel modes of resistance. Thus, in the development of novel antimicrobial compounds, it is critical to extensively survey clinical bacterial isolates for unusual patterns of resistance. Any resistant strains that are observed should be subjected to a thorough molecular biological analysis in order to understand the underlying mechanisms of resistance and intraspecific genetic variation.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Becker for laboratory work in surveying S. pnuemoniae isolates.

The Institute for Genomic Research acknowledges the U.S. Department of Energy, U.S. Office of Naval Research, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and DERA for support of the B. anthracis genome project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown, J. R. 1998. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Evolution of a troubled family, p. 217-230. In J. Wiegel and M. W. W. Adams (ed.), Thermophiles: the keys to molecular evolution and the origin of life? Taylor and Francis Ltd., London, United Kingdom.

- 3.Brown, J. R., J. Zhang, and J. E. Hodgson. 1998. A bacterial antibiotic resistance gene with eukaryotic origins. Curr. Biol. 8:R365-R367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyke, K. G. H., S. P. Curnock, M. Golding, and W. C. Noble. 1991. Cloning of the gene conferring resistance to mupirocin in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 77:195-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Felmingham, D., and J. Washington. 1999. Trends in the antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial respiratory tract pathogens—findings of the Alexander Project 1992-1996. J. Chemother. 11:5-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuller, A. T., G. Mellows, M. Woolford, G. T. Banks, K. D. Barrows, and E. B. Chain. 1971. Pseudomonic acid: an antibiotic produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens. Nature 234:416-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbart, J., C. R. Perry, and B. Slocombe. 1993. High-level mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: evidence for two distinct isoleucyl-tRNA synthetases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 37:32-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Havarstein, L. S., G. Coomaraswamy, and D. A. Morrison. 1995. An un-modified heptadecapeptide pheromone induces competence for genetic transformation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:11140-11144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hodgson, J. E., C. P. Curnock, K. G. Dyke, R. Morris, D. R. Sylvestor, and M. S. Gross. 1994. Molecular characterization of the gene encoding high-level mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus J2870. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38:1205-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoskins, J., W. E. Alborn, Jr., J. Arnold, L. C. Blaszczak, S. Burgett, B. S. DeHoff, S. T. Estrem, L. Fritz, D. J. Fu, W. Fuller, et al. 2001. The genome of the bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae strain R6. J. Bacteriol. 183:5709-5717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jarvest, J. R., J. M. Berge, V. Berry, H. F. Boyd, M. J. Brown, J. S. Elder, A. K. Forrest, A. P. Fosberry, D. R. Gentry, M. J. Hibbs, D. D. Jaworski, P. J. O'Hanlon, A. J. Pope, S. Rittenhouse, R. J. Sheppard, C. Slater-Radosti, and A. Worby. 2002. Nanomolar inhibitors of Staphylococcus aureus methionyl tRNA synthetase with potent antibacterial activity against gram-positive pathogens. J. Med. Chem. 45:1952-1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacks, S. 1966. Integration efficiency and genetic recombination in pneumococcal transformation. Genetics 53:207-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Leblanc, D. J., L. N. Lee, and A. Abu-Al-Jaibat. 1992. Molecular genetic, and functional analysis of the basic replicon of pVA380-1, a plasmid of oral streptococci origin. Plasmid 28:130-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne, D. J., N. B. Wallis, D. R. Gentry, and M. Rosenberg. 2000. The impact of genomics on novel antibacterial targets. Curr. Opin. Drug Disc. Dev. 3:177-190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 15.Sutherland, R., R. J. Boon, K. E. Griffin, P. J. Masters, B. Slocombe, and A. R. White. 1985. Antibacterial activity of mupirocin (pseudomonic acid), a new antibiotic for topical use. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 27:495-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tettelin, H., K. E. Nelson, I. T. Paulsen, J. A. Eisen, T. D. Read, S. Peterson, J. Heidelberg, R. T. DeBoy, D. H. Haft, R. J. Dodson, et al. 2001. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Science 293:498-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woese, C. R., G. J. Olsen, M. Ibba, and D. Söll. 2000. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, the genetic code, and the evolutionary process. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64:202-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]