Abstract

There are no effective therapeutics for treating invasive Scedosporium prolificans infections. Doses of 15, 25, and 50 mg/kg of body weight/day for the new triazole albaconazole (ABC) were evaluated in an immunocompetent rabbit model of systemic infection with this mold. Treatments were begun 1 day after challenge and given for 10 days. ABC at any dose was more effective than amphotericin B (AMB) at 0.8 mg/kg/day at clearing S. prolificans from tissue (P < 0.007). The percentages of survival at 25 mg of ABC/kg/day were similar to those obtained with AMB. Rabbits showed 100% survival when they were treated with 50 mg of ABC per kg (P < 0.0001 versus control group), and only this dosage was able to reduce tissue burden significantly in the five organs studied, i.e., spleen, kidneys, liver, lungs, and brain.

Scedosporium prolificans is an emerging filamentous fungus that infects both immunosuppressed and healthy patients, and it is the most common agent of disseminated phaeohyphomycosis (2, 11, 14, 15, 20). The infection is probably mostly acquired by inhalation of conidia and can take a wide variety of forms. Disseminated infection is associated mainly with patients with underlying blood malignancies and is usually fatal. The infection is generally treated with amphotericin B (AMB) and occasionally with other drugs, although the outcome is not often successful (2, 9, 15, 20). Several in vitro studies have demonstrated that S. prolificans is generally resistant to the antifungal agents available, and this correlates with the poor clinical response (5, 7). In a previous paper, we demonstrated that high doses of liposomal amphotericin B (10 mg/kg of body weight/day) combined with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor were moderately effective in the treatment of murine scedosporiosis (18). However, further studies are required to determine whether more appropriate dosages of the drug and more suitable strategies that combine it with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or other lymphokines provide better results. Another alternative, which is practically unexplored, is to use a therapy combining two antifungal agents. In vitro studies have demonstrated that itraconazole combined with terbinafine has a synergic effect against clinical isolates of this fungus (16). This is a line of investigation that deserves to be developed, although the rapid clearance of both drugs in mice makes it necessary to use other animal models for testing this combination. In spite of these promising approaches, alternative treatments for these severe and increasingly frequent mycoses still need to be investigated. The new triazole albaconazole (ABC) showed good in vitro activity against this fungus in a recent study which tested 30 strains (5). This drug has also shown good in vitro activity against dermatophytes, Aspergillus, Paecilomyces, and Candida species, among others (4, 8, 19). The concentrations of this drug achieved in plasma of mice are very low, and its half-life is short; however, its pharmacokinetics and bioavailability are excellent in rabbits (1). The aim of the present study was to develop a rabbit model of systemic infection by S. prolificans to evaluate the efficacy of an escalation in dose of ABC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

Two strains of S. prolificans, FMR 6654 and FMR 3569, isolated from human blood, were used.

Animals.

New Zealand White male rabbits (weight, ca. 2.5 kg) obtained from San Bernardo S.L., Navarra, Spain, were used in the study. The rabbits were individually housed and were maintained with water and standard rabbit feed ad libitum. They were monitored daily for 18 days. Conditions were approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the Rovira i Virgili University.

Inoculum preparation.

The strains were retrieved from storage in slant cultures with sterile paraffin oil and were subcultured on potato dextrose agar plates at 30°C for 7 to 10 days. The inoculum was prepared as described in previous studies (18). Rabbits were infected intravenously via a lateral ear vein.

Model infection.

To determine a suitable lethal dose, groups of five rabbits were established. Three inocula of two different strains were tested, i.e., 5 × 106, 1 × 107, and 1 × 108 CFU of the strain FMR 6654/animal and 5 × 106, 1 × 107, and 5 × 108 CFU of the strain FMR 3569/animal. Animals were checked daily for 18 days.

Antifungal agents.

ABC (Uriach & cía., Barcelona, Spain) was dissolved in 0.2% carboxymethylcellulose and 1% Tween 80 in distilled water at a concentration of 125 mg/ml. AMB (Fungizona; Squibb Industria Farmaceutica, Barcelona, Spain) was dissolved in distilled water for a final stock solution of 5 mg/ml. The final concentration for administration was prepared in 5% dextrose.

Treatments.

After screening two strains of S. prolificans at different concentrations of inocula, animals, in groups of eight, were infected with an inoculum of 107 CFU of the strain FMR 6654. Treatments began 24 h after infection and were given once daily for 10 days. ABC was administered orally with a 5-ml syringe with an attached animal feeding needle at 15, 25, and 50 mg/kg. AMB was administered intravenously as a bolus, via a lateral ear vein, at 0.8 mg/kg. The control group received oral placebo treatment, i.e., 0.2% carboxymethylcellulose and 1% TWEEN 80 in distilled water.

Tissue burden study.

Animals which experienced paralysis, convulsion, or prolonged anorexia or dehydration or survived to the end of the experiment were sacrificed by injecting a concentrated pentobarbital solution intravenously (22). Kidneys, spleen, liver, lungs, and brain were collected, and portions of 1 g of each organ were homogenized in 2 ml of 0.9% saline. Homogenates were serially diluted in saline and plated in duplicate on potato dextrose agar, and colonies were counted after 96 h of incubation at 30°C.

Histopathology.

A portion of each specimen was placed in 10% buffered formalin for the histopathological study. Organs were sectioned in a paraffin block, and the sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin, periodic acid Schiff, and Grocott methenamine silver (6).

Statistical methods.

Survival rates were evaluated with the Kaplan-Meyer test using Graph Pad Prism software, version 3.00 for Windows. Organ burdens were converted to log10 CFU and compared using the Mann-Whitney U test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In general mortality correlated with the size of the inocula. The largest inoculum (108 CFU) of the strain FMR 6654 was highly lethal (100% mortality in 5 days) for rabbits with a mean survival time (MST) of 4 days. The rabbits infected with 107 CFU died between 4 and 10 days postinfection (MST = 7.13 days). With the smallest inoculum (5 × 106 CFU), only two animals died in 18 days. Rabbits infected with 5 × 108 CFU of strain FMR 3569 showed an MST of 2 days. Animals which received an inoculum of 107 CFU of that strain had an MST of 11.5 days, and those infected with 5 × 106 CFU had 100% survival (MST > 18 days).

Inocula of 107 for both strains were tested again in triplicate. The results obtained with the strain FMR 6654 were more reproducible (MST = 7.19 ± 0.32 days) than with strain FMR 3569 (MST = 9.58 ± 4.69 days). On the basis of these results, an inoculum of 107 CFU of strain FMR 6654/animal was chosen for the study.

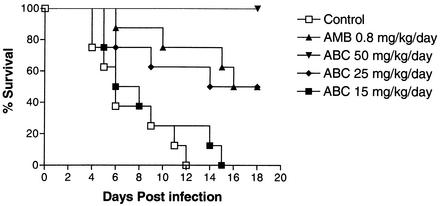

Figure 1 shows the survival curves for the treated animals and the control group. Untreated animals began to die 4 days postinfection, and by day 12 no animal survived (MST = 7.12). The mortality of the animals treated with ABC at 15 mg/kg/day was similar (MST = 7.25) to that of the control group (P = 0.34). Animals treated with ABC at 25 mg/kg/day or AMB at 0.8 mg/kg/day showed 50% survival (MST = 13.37 and 14.87, respectively), and survival rates were significantly greater than those for untreated animals (P < 0.01). All the animals that received ABC at 50 mg/kg/day survived at the end of the experiment (P < 0.0001 versus control group results).

FIG. 1.

Survival curves of rabbits infected with 107 CFU of S. prolificans FMR 6654.

CFU counts from semiquantitative cultures of spleen, kidney, liver, lung and brain are shown in Table 1. The organs of all the untreated animals, in particular the kidneys, were extensively infected. The animals treated with ABC at all tested doses had lower tissue burdens than the control group. S. prolificans was undetectable in the liver, spleen, and lung cultures. AMB reduced tissue burden significantly in the liver and spleen (P = 0.002 and 0.012 versus control group results, respectively), but ABC was more effective at all doses in the spleen (P < 0.001 versus AMB group results). In lung tissue, AMB reduced colony counts but not significantly (P = 0.061). However, all the animals that received ABC showed negative cultures from this organ (P < 0.007 versus AMB results; P < 0.001 versus results for untreated animals). In the kidney and brain, only animals receiving ABC at a dose of 50 mg/kg/day significantly reduced tissue burden in comparison to the control group (P < 0.001 and P = 0.023, respectively).

TABLE 1.

Semiquantitative results of organ cultures of rabbits treated with antifungal therapy begun 24 h after challenge

| Groupg | Log10 geometric mean CFU/g [95% CIf] (no. of positive cultures/no. of rabbits cultured)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spleen | Kidney | Liver | Lung | Brain | |

| Control | 2.17 [2.15-2.27] (8/8) | 3.94 [3.5-4.71] (8/8) | 2.01 [1.54-2.48] (8/8) | 2.82 [2.68-2.94] (8/8) | 2.42 [1.50-3.34] (8/8) |

| AMB | 1.43 [0.91-1.95]c (6/8) | 3.44 [2.88-4.00] (8/8) | 0.58 [−0.32-1.47]c (2/8) | 1.70 [0.17-3.22] (4/8) | 0.95 [−5.22-2.43] (2/8) |

| ABC 15 | 0b,d (0/8) | 2.94 [2.21-3.71] (8/8) | 0d (0/8) | 0a,d (0/8) | 1.08 [0.10-2.07] (4/8) |

| ABC 25 | 0b,d (0/8) | 3.21 [2.80-3.44] (8/8) | 0d (0/8) | 0a,d (0/8) | 1.11 [0.11-2.10] (4/8) |

| ABC 50 | 0b,d (0/8) | 0.33 [−0.27-0.95]b,d (1/8) | 0d (0/8) | 0a,d (0/8) | 0.42 [−0.23-1.08]c (2/8) |

P < 0.007 versus values obtained with AMB.

P < 0.001 versus values obtained with AMB.

P < 0.012 versus values obtained with control.

P < 0.001 versus values obtained with control.

P = 0.023 versus values obtained with control.

CI, confidence interval.

Drug and dose in milligrams/kilogram/day are given.

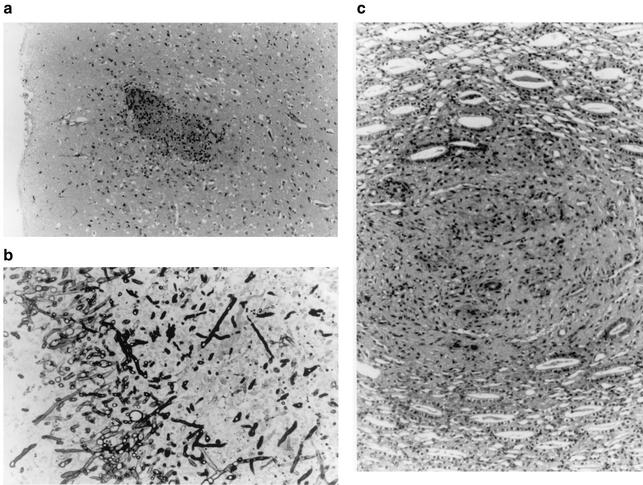

The histopathological study confirmed that the kidney was the organ that was most affected, but no visible lesions were observed in the liver, lung, or spleen from either treated or untreated animals. In control animals, the kidney showed numerous micro- and macroabscesses with central necrotic areas, considerable inflammatory cell response, and numerous fungal elements in parenchymatous tissue (Fig. 2b) and the pelvis. Small areas of glomerular and tubular necrosis with hyphae and conidia were observed. Approximately 20% of control animals showed microabscesses in the brain (Fig. 2a). The histopathological features of the animals treated with the lowest doses of ABC were similar to those of the untreated group. No lesions, however, were found in the brain. AMB or ABC at 25 mg/kg/day attenuated the histopathological severity in the kidney the same as in controls. In both groups, abscesses with some inflammatory and fungal cells were observed. No histological damage was observed in the central nervous system.

FIG. 2.

(a) Subcortical microabscess in the brain of an untreated animal. Periodic acid Schiff stain (magnification, ×60). (b) Fungal growth in parenchymatic tissue of kidney of an untreated animal. Grocott stain was used (magnification, ×240). (c) Area of tissue regeneration after a necrotic process in renal parenchyma. Animal was treated for 10 days with ABC at 50 mg/kg/day. Periodic acid Schiff stain was used (magnification, ×200).

The least renal affection was observed in animals that received ABC at a rate of 50 mg/kg/day. In this group, only small residual foci with few or no fungal cells were observed. It is worth mentioning that in the animals of this group, areas with postnecrotic tissular regeneration, without inflammatory or fungal cells, were also present (Fig. 2c). No signs of toxicity were detected in any of the treated animals.

Up to now murine models were the only models developed to study Scedosporium infections in animals (3, 17, 18). The mouse is usually the animal of choice for infections by numerous fungal species because of its availability and the large accumulation of information regarding its pathophysiology. However, in our case the pharmacokinetics of ABC in mice was not useful. The rapid clearance of ABC in mice makes these animals unsuitable for testing efficacy. Consequently, we established a reproducible model of acute scedosporiosis in rabbits and demonstrated that the severity of the infection is determined by the size of the inoculum. Although not as commonly used as mice, rabbits have been useful for testing several drugs against systemic infections by different species of filamentous fungi (12, 13, 21, 22). In the development of our rabbit model, we have followed some of the procedures used in such studies. In our model, the infection was especially acute in the kidneys and brain, where abscesses and hyphae were clearly evident. Previously, we had also noticed tropism of S. prolificans for these organs in mice (3). The results of our present study demonstrated that ABC has therapeutic efficacy against systemic scedosporiosis in nonimmunosuppressed animals. This is important because the fungus causes infections not only in neutropenic patients but also in immunocompetent people (10, 23). In the latter, the fungus usually causes bone and joint infections and locally invasive diseases. Infections by S. prolificans have increased dramatically in recent years, and it is now one of the most common filamentous fungi that cause systemic infections in humans. In a recent review of disseminated phaeohyphomycosis reported in the last decade, S. prolificans was by far the most common species (20). The fact that even low doses of ABC were able to reduce tissue burden more effectively than AMB and that at higher doses rabbits reached 100% survival is very hopeful, because so far there have been no effective treatments of systemic scedosporiosis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartolí, J., E. Turmo, M. Algueró, E. Boncompte, M. L. Vericat, L. Conte, J. Ramis, M. Merlos, J. García-Rafanell, and J. Forn. 1998. New azole antifungal. 3. Synthesis and antifungal activity of 3-substituted-4 (3H)-quinazolinones. J. Med. Chem. 41:1869-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berenguer, J., J. L. Rodríguez-Tudela, C. Richard, M. Álvarez, M. A. Sanz, L. Gaztelurrutia, J. Ayats, and J. V. Martínez-Suárez. 1997. Deep infections caused by Scedosporium prolificans. A report on 16 cases in Spain and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 76:256-265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cano, J., J. Guarro, E. Mayayo, and J. Fernández-Ballart. 1992. Experimental infection with Scedosporium inflatum. J. Med. Vet. Mycol. 30:413-420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capilla, J., M. Ortoneda, F. J. Pastor, and J. Guarro. 2001. In vitro antifungal activities of the new triazole UR-9825 against clinically important filamentous fungi. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2635-2637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrillo, A. J., and J. Guarro. 2001. In vitro activities of four novel triazoles against Scedosporium spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2115-2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiller, T. M., J. Capilla-Luque, R. A. Sobel, K. Farrokhshad, K. V. Clemons, and D. A. Stevens. 2002. Development of a murine model of cerebral aspergillosis. J. Infect. Dis. 186:574-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuenca-Estrella, M., B. Ruiz-Díez, J. V. Martínez-Suárez, A. Monzón, and J. L. Rodríguez-Tudela. 1999. Comparative in-vitro activity of voriconazole (UK-109, 496) and six other antifungal agents against clinical isolates of Scedosporium prolificans and Scedosporium apiospermum. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 43:149-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernández-Torres, B., A. J. Carrillo, E. Martín, A. del Palacio, M. K. Moore, A. Valverde, M. Serrano, and J. Guarro. 2001. In vitro activities of 10 antifungal drugs against 508 dermatophyte strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2524-2528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gosbell, I. B., M. L. Morris, J. H. Gallo, K. A. Weeks, S. A. Neville, A. H. Rogers, R. H. Andrews, and D. H. Ellis. 1999. Clinical, pathologic and epidemiologic features of infection with Scedosporium prolificans: four cases and review. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 5:672-686. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greig, J. R., M. A. Khan, N. S. Hopkinson, B. G. Marshall, P. O. Wilson, and S. U. Arman. 2001. Pulmonary infection with Scedosporium prolificans in an immunocompetent individual. J. Infect. 43:15-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoog, G. S., F. D. Marvin-Sikkema, G. A. Lahpoor, J. C. Gottschall, R. A. Prins, and E. Guého. 1994. Ecology and physiology of the emerging opportunistic fungi Pseudallescheria boydii and Scedosporium prolificans. Mycoses 37:71-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamei, K. 2000. Animal models of zygomycosis—Absidia, Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, and Cunninghamella. Mycopathologia 152:5-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirkpatrick, W. R., R. K. McAtee, A. W. Fothergill, D. Loebenberg, M. G. Rinaldi, and T. F. Patterson. 2000. Efficacy of SCH56592 in a rabbit model of invasive aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:780-782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.López, L., L. Gaztelurrutia, M. Cuenca-Estrella, A. Monzón, J. Barrón, J. L. Hernández, and R. Pérez. 2001. Infección y colonización por Scedosporium prolificans. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 19:308-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maertens, J., K. Lagrou, H. Deweerdt, I. Surmon, G. E. Verhoef, J. Verhaegen, and M. A. Boogaerts. 2000. Disseminated infection by Scedosporium prolificans: an emerging fatality among hematology patients. Case report and review. Ann. Hematol. 79:340-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meletiadis, J., J. W. Mouton, J. L. Rodríguez-Tudela, J. F. Meis, and P. E. Verweij. 2000. In vitro interaction of terbinafine with itraconazole against clinical isolates of Scedosporium prolificans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2:470-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ortoneda, M., F. J. Pastor, E. Mayayo, and J. Guarro. 2002. Comparison of the virulence of Scedosporium prolificans strains from different origins in a murine model. J. Med. Microbiol. 51:924-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ortoneda, M., J. Capilla, I. Pujol, F. J. Pastor, E. Mayayo, J. Fernández-Ballart, and J. Guarro. 2002. Liposomal amphotericin B and granulocyte colony stimulating factor therapy in a murine model of invasive infection by Scedosporium prolificans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 49:525-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramos, G., M. Estrella-Cuenca, A. Monzón, and J. L. Rodríguez-Tudela. 1999. In-vitro comparative activity of UR-9825, itraconazole and fluconazole against clinical isolates of Candida spp. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 44:283-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Revankar, S. G., J. E. Patterson, D. A. Sutton, R. Pulen, and M. G. Rinaldi. 2002. Disseminated phaeohyphomycosis: review of an emerging mycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 34:467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roberts, J., K. Schock, S. Marino, and V. T. Andriole. 2000. Efficacies of two new antifungal agents, the triazole ravuconazole and the echinocandin LY-303366, in an experimental model of invasive aspergillosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:3381-3388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams, P. L., R. A. Sobel, K. N. Sorensen, K. V. Clemons, L. M. Shuer, S. S. Royaltey, Y. Yao, D. Pappagianis, J. E. Lutz, C. Reed, M. E. River, B. C. Lee, S. U. Bhatti, and D. A. Stevens. 1998. A model of coccidioidal meningoencephalitis and cerebrospinal vasculitis in the rabbit. J. Infect. Dis. 178:1217-1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wood, G. M., J. G. McCormack, D. B. Muir, D. H. Ellis, M. F. Ridley, R. Pritchard, and M. Harrison. 1992. Clinical features of human infection with Scedosporium inflatum. Clin. Infect. Dis. 14:1027-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]