Abstract

We investigated the molecular basis of the activity of 4-phenoxyphenoxyethyl thiocyanate (WC-9) against Trypanosoma cruzi, the etiological agent of Chagas’ disease. We found that growth inhibition of T. cruzi epimastigotes induced by this compound was associated with a reduction in the content of the parasite's endogenous sterols due to a specific blockade of their de novo synthesis at the level of squalene synthase.

There is an urgent need for safer and more potent drugs for the specific treatment of Chagas’ disease, the largest parasitic disease burden in Latin America. Currently available drugs have serious limitations due to limited efficacy, particularly in the chronic stage of the disease, and frequent toxic side effects (25). The etiological agent of Chagas’ disease, the kinetoplastid protozoan Trypanosoma cruzi, has a complex life cycle with proliferative and infective stages in both its insect (Reduviidae) vectors and mammalian hosts, where the parasite develops intracellularly, leading to tissue damage compounded by the ensuing inflammatory response (2). There are 16 to 18 million people already infected in Latin America. Most of them are in the chronic stage of the disease, in which 30 to 40% will develop serious, often lethal, cardiac and gastrointestinal tract lesions (7, 25).

We have recently described the potent and selective in vitro activity of 4-phenoxyphenoxy and aryloxyethyl derivatives against both the extracellular epimastigote and the clinically relevant intracellular amastigote forms of T. cruzi, but the molecular mechanisms of these effects remained unclear (4, 8). T. cruzi and related trypanosomatid parasites have a strict requirement for specific endogenous sterols (ergosterol and analogs) for survival and growth and cannot use the abundant supply of cholesterol present in their mammalian hosts (14-17). We have shown that ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors with potent in vitro activity and special pharmacokinetic properties in mammals (large volumes of distribution and long half-lives) can induce radical parasitological cure in animal models of both acute and chronic experimental Chagas’ disease (14-18). We decided to investigate the possible effect of 4-phenoxyphenoxyethylthiocyanate (WC-9), the most potent member of this group of compounds, on the de novo sterol biosynthesis in intact T. cruzi epimastigotes, because previous work indicated interference by this type of compounds with steroid biogenesis in mammals (22, 23).

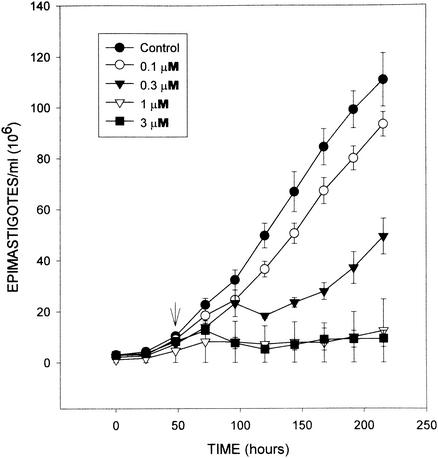

WC-9 induced a dose-dependent effect on growth of the epimastigote form of the EP strain of parasite (Fig. 1). When the EP strain was grown in liver infusion tryptose (LIT) medium (6), the MIC for the organism (defined as the minimal concentration required to inhibit growth by >99% after 96 h) was 1 μM, in agreement with previous results with the Y strain (4). We analyzed the free sterol contents of control and treated cells by capillary gas-liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (18-21). We found (Table 1) that the growth-inhibitory effects of WC-9 were associated with a depletion of the parasite's endogenous sterols, ergosterol and its 24-ethyl analog, and a concomitant increase in the relative proportion of cholesterol, which is taken passively from the growth medium by the epimastigotes (18-21). At the MIC, an almost complete disappearance of the parasite's sterols was observed, with no accumulation of sterol intermediates (Table 1) (see reference 21 for a detailed description of the sterol biosynthesis pathway in T. cruzi epimastigotes) or precursors, such as lanosterol or squalene (not shown). These facts indicated a blockade of the biosynthetic pathway at a presqualene level (18).

FIG. 1.

Effects of compound WC-9 on the proliferation of T. cruzi epimastigotes. Epimastigotes were cultured in LIT medium at 28°C with strong aeration. An arrow indicates the time the drug was added at the indicated concentrations. Cell densities were measured by turbidity at 560 nm and by direct counting with a hemocytometer. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and each bar represents 1 standard deviation.

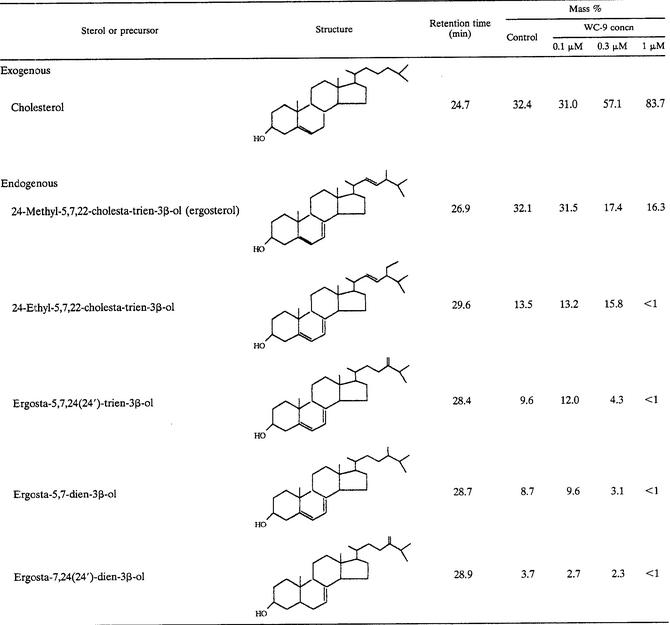

TABLE 1.

Free sterols and precursors present in T. cruzi epimastigotes (EP stock) grown in the presence or absence of WC-9a

Sterols were extracted from T. cruzi epimastigotes cultured in LIT medium for 120 h in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of WC-9; they were separated from polar lipids by silicic acid column chromatography and analyzed by quantitative capillary gas-liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry (18-21).

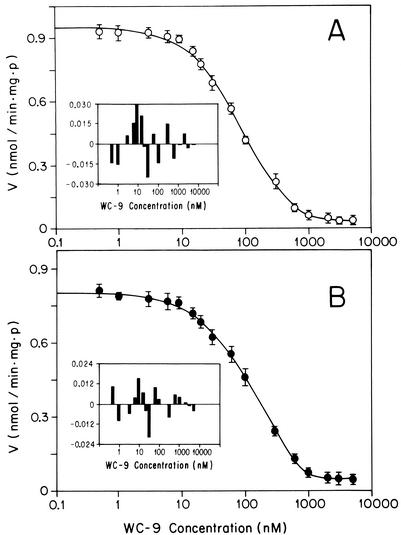

To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of compound WC-9 on two key enzymes of the poly-isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway: farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS [EC 5.3.3.2]) and squalene synthase (SQS [EC 2.5.1.1]). The product of the reaction catalyzed by FPPS, farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), is the main branching point of the poly-isoprenoid pathway, while SQS catalyzes the first committed step in sterol biosynthesis, in which a reductive dimerization of two molecules of FPP yields squalene. Using a recombinant T. cruzi FPPS expressed in Escherichia coli as previously described (10), we found that WC-9 was essentially inactive against this enzyme (9% inhibition at 4 μM and 13% inhibition at 40 μM). Turning to SQS, we used as an enzyme source highly purified glycosomes and mitochondrial membrane vesicles obtained from T. cruzi epimastigotes gently broken by abrasion with silicon carbide and fractionated by differential and isopycnic centrifugation (5, 18). SQS was assayed by a radioactive spot wash assay (12). The results (Fig. 2) indicated that WC-9 is a potent inhibitor of both glycosomal and mitochondrial T. cruzi SQS, with 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50) of 88 and 129 nM, respectively, at saturating concentrations of the enzyme substrates (25 μM FPP and 1 mM NADPH). The inhibitory activities of WC-9 on purified SQS can readily explain the effects of this compound on the free sterol composition (Table 1) and growth (Fig. 1) of whole epimastigotes and strongly suggest a causal relationship between the latter two phenomena. The dose-response curves for the activity of WC-9 against T. cruzi SQS (Fig. 2) were consistent with noncompetitive inhibition, with Ki = IC50; these Ki values are 2 to 3 orders of magnitude lower than the Km of the substrates (18). This suggested that WC-9, with its electrophilic sulfur center linked to the relatively nonpolar (hydrophobic) 4-phenoxyphenoxyethyl moiety, could act by mimicking the carbocationic transition state of the reaction, leading to formation of the cyclopropylcarbinyl intermediate presqualene diphosphate (1, 9, 11). A similar rationale has been advanced to explain the potent anti-SQS activity of aryl-quinuclidine derivatives against both mammalian SQS and T. cruzi SQS (3, 13, 18, 24). Based on this hypothesis, it should be possible to design new and more potent SQS inhibitors, using WC-9 as lead structure (i.e., by increasing the electrophilic character of the 4-phenoxyphenoxyethyl substituent).

FIG. 2.

Effects of WC-9 on activity of T. cruzi glycosomal (A) and mitochondrial (B) SQS in the presence of saturating substrate concentrations. The dose-response curves were fitted by nonlinear regression to the equation V = Vo {1 + ([I]/Ki)n}−1, where V is the measured enzyme activity, Vo is the control (uninhibited) activity, and Ki is the apparent inhibition constant. The results were Ki = 88 ± 4 nM and n = 1.05 ± 0.04 for the glycosomal enzyme and Ki = 129 ± 6 nM and n = 0.99 ± 0.03 for the mitochondrial enzyme, consistent with a noncompetitive inhibition. Insets show residuals of the regression.

In conclusion, our results indicate that a primary mechanism of the antiproliferative effects of WC-9 against T. cruzi is the depletion of essential endogenous sterols by a specific blockade of their de novo biosynthesis at the level of SQS. This is the first explanation at a molecular level of the mechanism of action of 4-phenoxyphenoxy derivatives against this parasite, and it suggests that this and related compounds could represent a new class of SQS inhibitors with potential antiparasitic and cholesterol-lowering activity in humans.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (55000620) and the Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research to J.A.U.; the UNDP/World Bank/World Health Organization Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (A00044) to R.D., J.A.U., and J.B.R.; and CONICET (PIP 635/98) and the Universidad de Buenos Aires (X-080) to J.B.R. J.A.U. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Research Scholar.

We thank Luis Alvarez for help with the preparation of figures.

Footnotes

We dedicate this paper to the memory of Zigman Brener, pioneer in experimental chemotherapy studies of Chagas’ disease.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blagg, B. S., M. B. Jarstfer, D. H. Rogers, and C. D. Poulter. 2002. Recombinant squalene synthase. A mechanism for the rearrangement of presqualene diphosphate to squalene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:8846-8853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brener, Z. 1992. Trypanosoma cruzi: taxonomy, morphology and life cycle, p. 13-29. In S. Wendel, Z. Brener, M. E. Camargo, and A. Rassi (ed.), Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis): its impact on tranfusion and clinical medicine. International Society for Blood Transfusion, São Paulo, Brazil.

- 3.Brown, G. R., A. J. Foubister, S. Freeman, P. J. Harrison, M. C. Johnson, K. B. Mallion, J. McCormick, F. McTaggart, A. C. Reid, G. J. Smith, and M. J. Taylor. 1996. Synthesis and activity of a novel series of 3-biarylquinuclidine squalene synthase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 39:2971-2979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cinque, G. M., S. H. Szajnman, L. Zhong, R. Docampo, A. J. Schvartzapel, J. B. Rodriguez, and E. G. Gros. 1998. Structure-activity relationship of new growth inhibitors of Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Med. Chem. 41:1540-1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Concepcion, J. L., D. Gonzalez-Pacanowska, and J. A. Urbina. 1998. 3-Hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA reductase in Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: subcellular localization and kinetic properties. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 352:114-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Maio, A., and J. A. Urbina. 1984. Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: terminal oxidases in two growth phases in vitro. Acta Cient. Venez. 35:136-141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Docampo, R. 2001. Recent developments in the chemotherapy of Chagas' disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 7:1157-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elhalem, E., B. N. Bailey, R. Docampo, I. Ujváry, S. H. Szajnman, and J. B. Rodriguez. 2002. Design, synthesis and evaluation of aryloxyethyl thiocyanate derivatives against Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Med. Chem. 45:3984-3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jarstfer, M. B., D. L. Zhang, and C. D. Poulter. 2002. Recombinant squalene synthase. Synthesis of non-head-to-tail isoprenoids in the absence of NADPH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124:8834-8845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montalvetti, A., B. N. Bailey, M. B. Martin, G. W. Severin, E. Oldfield, and R. Docampo. 2001. Bisphosphonates are potent inhibitors of Trypanosoma cruzi farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 276:33930-33937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radisky, E. S., and C. D. Poulter. 2000. Squalene synthase: steady-state, pre-steady state and isotope-trapping studies. Biochemistry 39:1748-1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tait, R. M. 1992. Development of a radiometric spot-wash assay for squalene synthase. Anal. Biochem. 203:310-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ugawa, T., H. Kakuta, H. Moritani, K. Matsuda, T. Ishihara, M. Yamaguchi, S. Naganuma, Y. Iizumi, and H. Shikama. 2000. YM-53601, a novel squalene synthase inhibitor, reduces plasma cholesterol and triglycerides in several animal species. Br. J. Pharmacol. 131:63-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urbina, J. A. 1997. Lipid biosynthesis pathways as chemotherapeutic targets in kinetoplastid parasites. Parasitology 117:S91-S99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urbina, J. A. 2000. Sterol biosynthesis inhibitors for Chagas' disease. Curr. Opin. Anti-Infect. Inv. Drugs 2:40-46. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Urbina, J. A. 2001. Specific treatment of Chagas disease: current status and new developments. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 14:733-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Urbina, J. A. 2002. Chemotherapy of Chagas disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 8:287-295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urbina, J. A., J. L. Concepcion, S. Rangel, G. Visbal, and R. Lira. 2002. Squalene synthase as a chemotherapeutic target in Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania mexicana. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 125:35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Urbina, J. A., G. Payares, L. M. Contreras, A. Liendo, C. Sanoja, J. Molina, M. Piras, R. Piras, N. Perez, P. Wincker, and D. Loebenberg. 1998. Antiproliferative effects and mechanism of action of SCH 56592 against Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi: in vitro and in vivo studies. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:1771-1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urbina, J. A., G. Payares, J. Molina, C. Sanoja, A. Liendo, K. Lazardi, M. M. Piras, R. Piras, N. Perez, P. Wincker, and J. F. Ryley. 1996. Cure of short- and long-term experimental Chagas disease using D0870. Science 273:969-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Urbina, J. A., J. Vivas, G. Visbal, and L. M. Contreras. 1995. Modification of the sterol composition of Trypanosoma (Schizotrypanum) cruzi epimastigotes by Δ24(25) sterol methyl transferase inhibitors and their combinations with ketoconazole. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 73:199-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vladusic, E. A., O. P. Pignataro, L. E. Bussmann, and E. H. Charreau. 1995. Regulation of cholesterol ester cycle and progesterone synthesis by juvenile hormone in MA-10 Leydig tumor cells. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 52:83-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vladusic, E. A., O. P. Pignataro, L. E. Bussmann, A. M. Stoka, J. B. Rodriguez, E. G. Gros, and E. H. Charreau. 1994. Effect of juvenile hormone on mammalian steroidogenesis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 50:181-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward, W. H. J., G. A. Holdgate, S. Freeman, F. McTaggart, P. A. Girdwood, R. G. Davidson, K. B. Mallion, G. R. Brown, and M. A. Eakin. 1996. Inhibition of squalene synthase in vitro by 3-(biphenyl-4-yl)-quinuclidine. Biochem. Pharmacol. 51:1489-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. 1997. Thirteenth Programme report. UNDP/World Bank/World Health Organization Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.