Abstract

Chicory (Cichorium intybus) sesquiterpene lactones were recently shown to be derived from a common sesquiterpene intermediate, (+)-germacrene A. Germacrene A is of interest because of its key role in sesquiterpene lactone biosynthesis and because it is an enzyme-bound intermediate in the biosynthesis of a number of phytoalexins. Using polymerase chain reaction with degenerate primers, we have isolated two sesquiterpene synthases from chicory that exhibited 72% amino acid identity. Heterologous expression of the genes in Escherichia coli has shown that they both catalyze exclusively the formation of (+)-germacrene A, making this the first report, to our knowledge, on the isolation of (+)-germacrene A synthase (GAS)-encoding genes. Northern analysis demonstrated that both genes were expressed in all chicory tissues tested albeit at varying levels. Protein isolation and partial purification from chicory heads demonstrated the presence of two GAS proteins. On MonoQ, these proteins co-eluted with the two heterologously produced proteins. The Km value, pH optimum, and MonoQ elution volume of one of the proteins produced in E. coli were similar to the values reported for the GAS protein that was recently purified from chicory roots. Finally, the two deduced amino acid sequences were modeled, and the resulting protein models were compared with the crystal structure of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) 5-epi-aristolochene synthase, which forms germacrene A as an enzyme-bound intermediate en route to 5-epi-aristolochene. The possible involvement of a number of amino acids in sesquiterpene synthase product specificity is discussed.

The chicory (Cichorium intybus) plant contains bitter sesquiterpene lactones, such as lactucin, 8-deoxylactucin, and lactupicrin, in most of its organs e.g. (tap) roots, leaves, and stems and also in the etiolated heads, which are eaten as a vegetable in some parts of the world (Rees and Harborne, 1985; Beek et al., 1990; Price et al., 1990). These sesquiterpene lactones were shown to have significant anti-feedant activity (Rees and Harborne, 1985). In addition, Monde et al. (1990) demonstrated the induction of an anti-fungal guaianolide sesquiterpene lactone in chicory upon infection with Pseudomonas cichorii. Other composite plant species such as lettuce (Lactuca salva and Lactuca sativa), radicchio (Cichorium intybus), endive (Cichorium endiva), and artichoke (Cynara scolymus) have been demonstrated to contain similar sesquiterpene lactones as bitter constituents (Herrmann, 1978; Price et al., 1990). Several of these sesquiterpene lactones such as tenulin (from Helenium amarum), helenalin (from sneezeweed, Helenium autumnale), and parthenin (from Parthenium histerophorus) have been described as having anti-feedant activity on herbivorous insects and vertebrate herbivores (Picman, 1986). In addition, many sesquiterpene lactones were shown to possess pharmacological activities. For example, parthenolide from feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium) has an anti-migraine effect (Hewlett et al., 1996). Finally, anti-fungal, anti-bacterial, anti-protozoan, schistomicidal, and molluscicidal activities have been reported for many sesquiterpene lactones (Picman, 1986).

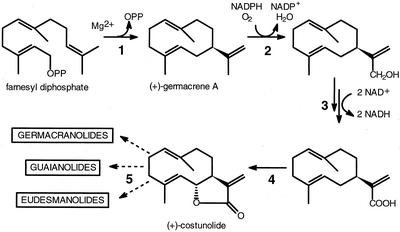

de Kraker et al. (1998, 2001, 2002) showed that the sesquiterpene lactones in chicory and probably also in a large number of other plant species originate from a common germacrane precursor, (+)-germacrene A. The biosynthesis of this sesquiterpene olefin from the ubiquitous sesquiterpene precursor farnesyl diphosphate (FDP) is catalyzed by a (+)-germacrene A synthase (GAS; Fig. 1). In a number of additional steps, the germacrene A precursor is oxidized into germacrene A carboxylic acid (de Kraker et al., 2001) that is further oxidized to produce the lactone ring (de Kraker et al., 2002). This is then further functionalized and/or cyclized to the respective guaianolide, eudesmanolide, and germacranolide sesquiterpene lactones (Fig. 1; de Kraker et al., 2002). The work by de Kraker et al. on the biosynthesis of sesquiterpene lactones was carried out using chicory taproots and, so far, little is known about the activity of the GAS in other plant organs or about its genetic regulation.

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic pathway of sesquiterpene lactones in chicory. Solid arrows indicate enzymatic steps previously demonstrated (de Kraker et al., 1998, 2001, 2002). 1, GAS; 2, germacrene A hydroxylase, 3, germacrene A alcohol dehydrogenase(s); 4, costunolide synthase; 5, further modifications. Broken arrows indicate postulated further steps (de Kraker et al., 2002).

In addition to being an intermediate in sesquiterpene lactone biosynthesis, germacrene A is in itself an important compound. For a long time, its detection in some systems escaped attention because of its rather high sensitivity to temperature and acidic conditions (de Kraker et al., 1998). However, (−)-germacrene A has been identified as the alarm pheromone in spotted alfalfa (Medicago sativa) aphids (Nishino et al., 1977). An unidentified enantiomer of germacrene A has been identified as an important constituent of spider mite induced volatiles in sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum; C. van de Boom, T.A. van Beek, and M. Dicke, unpublished data). Germacrene A has also been demonstrated to be an (enzyme-bound) intermediate in the biosynthesis of 5-epi-aristolochene and vetispiradiene, which are the sesquiterpene precursors of phytoalexins such as capsidiol and debneyol (Whitehead et al., 1989). Because of the importance of germacrene A both as an intermediate and as end product in many plant-organism interactions, we decided to clone and characterize the GAS-encoding cDNA from chicory.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

cDNA Isolation and Bacterial Expression

Degenerate primers designed on conserved areas of sesquiterpene synthases (Wallaart et al., 2001) were used in a reverse transcription PCR reaction to clone a sesquiterpene synthase homolog from (etiolated) chicory heads. Two different fragments with the expected length of about 550 bp were obtained. Sequencing of both fragments revealed homology to known sesquiterpene synthases present in public databases. We subsequently used both fragments as probes for cDNA library screening. This resulted in the isolation of two different, full-length cDNAs CiGASsh and CiGASlo containing a putative open reading frame of 1,674 (558 amino acids; hence, sh for short) and 1,749 bp (583 amino acids; hence, lo for long; Fig. 2). CiGASsh encodes a protein of 64.4 kD with a calculated pI of 4.89. CiGASlo encodes a protein of 67.1 kD with a calculated pI of 5.19. The two sequences exhibited 72% identity on the deduced amino acid level. Both genes exhibited highest homology with the (+)-δ-cadinene synthases from Gossypium arboreum (among others Q39760, Q39761, and O49853) and cotton (Gossypium hirsutum; P93665), the potato (Solanum tuberosum) vetispiradiene synthase (AAD02223), and the tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; T03714) and pepper (AJ005588) 5-epi-aristolochene synthases.

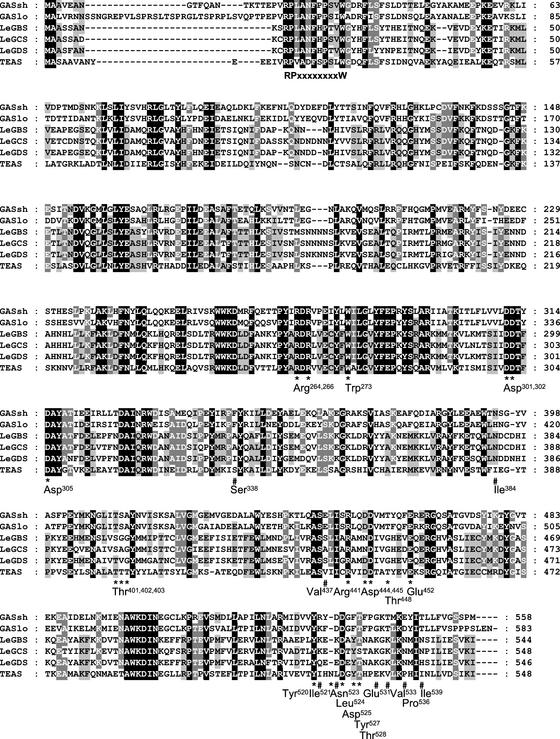

Figure 2.

Alignment of deduced amino acid sequences of chicory GASs, GASsh (=CiGASsh; GenBank accession no. AF498000) and GASlo (=CiGASlo; GenBank accession no. AF497999), with related plant sesquiterpene synthases: tomato germacrene B synthase (LeGBS; AAG41891), tomato germacrene C synthase (LeGCS; AAC39432), tomato germacrene D synthase (LeGDS; van der Hoeven et al., 2001), and tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase (TEAS; T03714). The amino acid residues marked with an asterisk and three-letter code and position correspond to the position in TEAS and were hypothesized by Chappell and coworkers to be involved in catalysis of TEAS (Starks et al., 1997). Residues marked with # are also discussed in the text. The alignment was made using the ClustalX and Genedoc software.

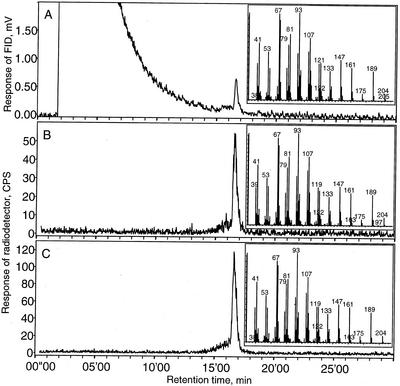

The catalytic activity of the two encoded proteins was examined using an enzyme assay on a cell-free extract of Escherichia coli BL 21 (DE3) harboring the two different cDNAs in the pET 11d vector. Radio-gas liquid chromatography (radio-GLC) showed that both extracts catalyzed the conversion of [3H]FDP to a radiolabeled product co-eluting with germacrene A (Fig. 3). A cell-free extract of E. coli BL 21 (DE3) harboring an empty vector did not produce any apolar radiolabeled products. GC-mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) analysis showed that retention times (not shown) and mass spectra (Fig. 3) of the major peak were identical to those of an authentic standard of germacrene A, thus, confirming that both cDNAs encode a GAS.

Figure 3.

Radio-GLC analysis of radiolabeled products formed from [3H]FDP in assays with protein extracts from transformed E. coli BL 21 (DE3) cells (Stratagene). A, Flame-ionization detector signal showing an unlabeled authentic standard of germacrene A. B and C, Radio traces showing enzymatic products of protein extracts from BL 21 (DE3) cells transformed with CiGASsh and CiGASlo, respectively. Insets show the mass spectra obtained using GC-MS analysis on an HP5-MS column of the same samples.

Finally, the possibility was checked that the two enzymes catalyze the formation of two different enantiomers of germacrene A. This was done by GC-MS analysis using an enantioselective column in combination with the principle of (stereoselective) heat-induced rearrangement of germacrene A to β-elemene (de Kraker et al., 1998). At an injection port temperature of 150°C, germacrene A was the major product of both the short and the long protein. Small amounts of α-selinene, β-selinene, and selina-4,11-diene, which are proton-induced rearrangement products (i.e. they are not produced enzymatically) were also detected (Teisseire, 1994; de Kraker et al., 1998; data not shown). When the injection port temperature was increased, only the (−)-enantiomer of β-elemene was formed from the germacrene A produced by both enzymes, implying that both clones encode enzymes exclusively producing (+)-germacrene A (de Kraker et al., 1998).

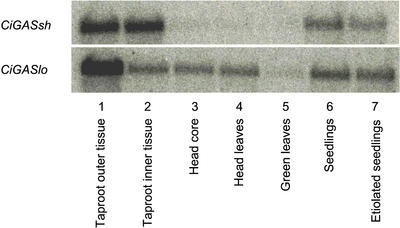

CiGASsh and CiGASlo Expression in Chicory

The expression of CiGASsh and CiGASlo in a number of chicory organs and tissues was analyzed. Both genes showed marked differences in expression, with CiGASsh being expressed particularly in taproot tissues (approximately equally in the outer and inner tissues) and in green and etiolated seedlings. Hardly any expression was detected in the head or in green leaves (Fig. 4). CiGASlo was expressed strongest in the outer taproot tissue, and much less in the inner taproot tissue. It was expressed at similar levels in head core tissue and leaves, and green and etiolated seedlings but at a much lower level in green leaves. The expression of the two genes in all tissues investigated correlates well with the observation that these tissues also contain sesquiterpene lactones (Beek et al., 1990). The evolutionary importance of the presence of two GASs in chicory is unclear. Perhaps it is significant that CiGASsh is preferentially expressed in the roots (that were also included as part of the seedlings) where accumulation of bitter sesquiterpene lactones is highest (Fig. 4; Rees and Harborne, 1985). CiGASsh has a lower Km and higher apparent Vmax than CiGASlo (see below) and this may also correlate with a higher accumulation of sesquiterpene lactones in roots.

Figure 4.

Western blot showing the expression of CiGASsh and CiGASlo in a number of chicory tissues. For each tissue and specific probe, 2 μg of total RNA was used (see “Materials and Methods” for more details).

Presence of GAS Isoenzyme Proteins in Chicory

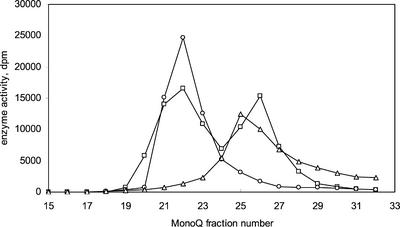

The fact that two GAS cDNAs were found was somewhat surprising because de Kraker et al. (1998) partially purified only one GAS from chicory roots. As a consequence, a protein extract was made from chicory heads from which the two cDNAs had also been obtained. This protein extract was partially purified using Q-Sepharose and MonoQ anion-exchange chromatography to confirm the presence of the two GAS proteins. The catalytic activity eluted as one peak from the Q-Sepharose column. However, on MonoQ, when using a slow gradient, the activity could be separated into two fractions (Fig. 5). Both these fractions were shown to produce radiolabeled germacrene A using radio-GLC (data not shown). The GASs that had been produced in E. coli were also chromatographed on the MonoQ column. The elution volumes of these proteins perfectly matched the elution volumes of the two plant GASs (Fig. 5). The difference in calculated pI of the two proteins did not correspond to the elution order from MonoQ. The protein with the lowest predicted pI (CiGASsh) eluted earlier. Finally, a sample of GAS purified from chicory roots using DE-52 anion exchanger as described by de Kraker et al. (1998) was also chromatographed on MonoQ. This sample showed only one peak of activity, which matched the elution volume of CiGASlo (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Elution from MonoQ of two GAS proteins CiGASsh (○) and CiGASlo (▵), that were obtained using heterologous expression in E. coli and a partially purified (using Q-Sepharose anion-exchange chromatography) protein extract prepared from chicory (□). Enzymatic activity of eluting fractions was assayed using [3H]FDP as substrate and determining hexane soluble radiolabeled product formation using scintillation counting. Product identity was verified using radio-GLC.

Enzyme Characterization

The proteins encoded by CiGASsh and CiGASlo (produced by bacterial expression) exhibited a pH optimum of 7.0 and 6.8, respectively. Enzymatic assays with the two MonoQ-purified E. coli-produced proteins were linear over a wide range of protein concentrations up to about 0.4 μg of protein per assay. Assays containing 0.2 μg of CiGASsh protein and 0.4 μg of CiGASlo protein were linear for up to 60 min at an FDP concentration as low as 2 μm. Although both proteins were only partially purified, the results suggest that the specific activity of the CiGASsh protein is about twice that of the CiGASlo protein. Kinetic analysis for both proteins yielded the typical hyperbolic saturation curves. The apparent Km and Vmax values for the substrate FDP were for CiGASsh 3.2 μm and 21.5 pmol h−1 μg−1 protein and for CiGASlo 6.9 μm and 13.9 pmol h−1 μg−1 protein. Both the pH optimum and the Km value of the long protein (pH 6.8 and 6.9 μm, respectively) are similar to the values reported for the GAS enzyme isolated from chicory roots (pH 6.7 and 6.6 μm, respectively; de Kraker et al., 1998). This supports the conclusion, based on the co-elution on MonoQ, that de Kraker et al. had purified the same long GAS protein from chicory roots. However, it is unclear why de Kraker et al. (1998) only found the CiGASlo encoded protein, when it is evident from the present study that, in addition to expression in the heads, both genes are also expressed in the roots (Fig. 4). It is possible that the CiGASsh encoded protein was lost during the purification procedure employed by de Kraker et al. (1998). The use of the weaker anion exchanger DE-52 (Whatman, Clifton, NJ) by these authors instead of the Q-Sepharose used here could be the reason for this loss, although the small difference in elution volume from MonoQ does not suggest that a large difference in elution from DE-52 would be expected.

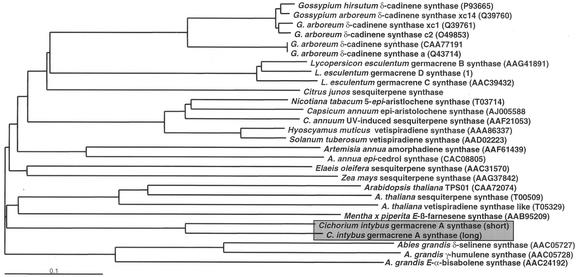

Phylogenetic Analysis

Phylogenetic analysis shows that the chicory GASs cluster separately from the other two Asteraceae sesquiterpene synthases, 5-epi-cedrol and amorpha-4,11-diene synthase from Artemisia annua (Fig. 6). It may be significant that chicory belongs to a separate subfamily of the Asteraceae, the Liguliflorae, whereas A. annua belongs to the Tubuliflorae. As reported before (Bohlmann et al., 1998), the gymnosperm sesquiterpene synthases isolated from grand fir (Abies grandis) diverged at an early stage from the angiosperm sesquiterpene synthases (Fig. 6). The only two monocotyledonous sesquiterpene synthases present in GenBank from Elais oleifera and maize (Zea mays) also cluster together (although the catalytic function of these two sequences has not yet been proven by heterologous expression). The catalytic activity of the Arabidopsis sesquiterpene synthase-like sequences that all cluster together has also not yet been demonstrated. Most of the Solanaceous tobacco, pepper, and Hyoscyamus muticus sesquiterpene synthases group together closely, with the exception of the tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) germacrene synthases. It may be significant that the former group contains elicitor/pathogen-induced sesquiterpene synthases, whereas those from tomato are constitutively expressed genes.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of sesquiterpene synthases (from Van der Hoeven et al., 2001).

The public databases contain a number of sequences that were isolated from one or a number of closely related species encoding either isoenzyme sesquiterpene synthases or sesquiterpene synthases with a different catalytic function. In Gossypium spp., for example, a large number of (+)-δ-cadinene synthase isoenzymes have been reported. Many of these have apparently only evolved relatively recently, although there is one branch that diverged earlier. The germacrene synthases in tomato have diverged relatively recently, even though each has a different product specificity. In contrast, the chicory GASs have diverged even earlier than the vetispiradiene synthases of two different species (potato and H. muticus).

In Figure 2, the most obvious difference between the two chicory GASs and the other sesquiterpene synthases is the presence of additional amino acids at the N-terminal end of the sequence, especially for CiGASlo. The presence of these amino acids is usually restricted to monoterpene synthases, which have about 40 to 60 additional amino acids upstream of an RRxxxxxxxxW motif of which the tandem Arg is supposed to be involved in plastid-targeting (Bohlmann et al., 2000). In all sesquiterpene synthases, the second Arg of this targeting motif has changed to a Pro (Fig. 2). The high degree of conservation of this motif in the sesquiterpene synthases suggests that, although it is no longer a targeting signal, the motif may still play a role in the catalytic activity of the enzymes. Trapp and Croteau (2001) postulated that the terpene synthases have all evolved from a common diterpene synthase ancestor bearing a targeting signal and that was likely involved in primary metabolism. During the evolution of the sesquiterpene synthases, this targeting signal was lost. However, the chicory GASs still bear the remnants of this targeting signal just as the putative Arabidopsis sesquiterpene synthases and Mentha β-farnesene synthase. This is supported by the phylogenetic grouping of these three species and their early divergence from the other sesquiterpene synthases (Fig. 6).

Comparison with the Tobacco TEAS

Chappell and coworkers were the first to crystallize a plant sesquiterpene synthase, the tobacco TEAS (Starks et al., 1997). TEAS was shown to produce germacrene A as an enzyme-bound intermediate that is not released by the enzyme but is further cyclized to produce the bicyclic 5-epi-aristolochene. As a consequence, because a considerable part of the catalytic reaction is the same, TEAS is considered a suitable reference material for the two chicory GASs.

Chappell and coworkers postulated that the further cyclization of the enzyme-bound intermediate germacrene A to 5-epi-aristolochene is moderated by the presence of one amino acid residue, Tyr-520. This was later confirmed by Rising et al. (2000) who introduced a mutation Tyr-520/Phe into the TEAS cDNA, causing the mutated protein to produce germacrene A instead of 5-epi-aristolochene (at 3% of the original activity). Chappell and coworkers recognized that support for their results should come from the isolation of the GAS from chicory that had been characterized biochemically by de Kraker et al. (1998; Rising et al., 2000). The isolation of not just one but two GASs with fairly low homology (considering that they encode isoenzymes) presents a good opportunity to study the importance of the active-site amino acids for the formation of germacrene A, the termination of the cyclization reaction at germacrene A, and the further cyclization to 5-epi-aristolochene.

In Figure 2, the amino acids hypothesized to be involved in the catalysis of TEAS by Chappell and coworkers, are indicated with an asterisk (Starks et al., 1997; Rising et al., 2000). Most of these amino acids are conserved in the chicory GASs (as well as in most of the other germacrene synthases) and, thus, apparently do not determine product specificity. The exceptions are Thr-402,403, Asn-523, and Tyr-527. Of these, the change of Thr-403 to Ala and of Tyr-527 to Phe constitute significant alterations in polarity. The larger number of amino acids between Tyr-520 and Asp-525 in TEAS (and the H. muticus vetispiradiene synthase, not shown) compared with all the other germacrene synthases, due to the deletion of Asn-523 (Fig. 2), may be significant as well because it is highly conserved.

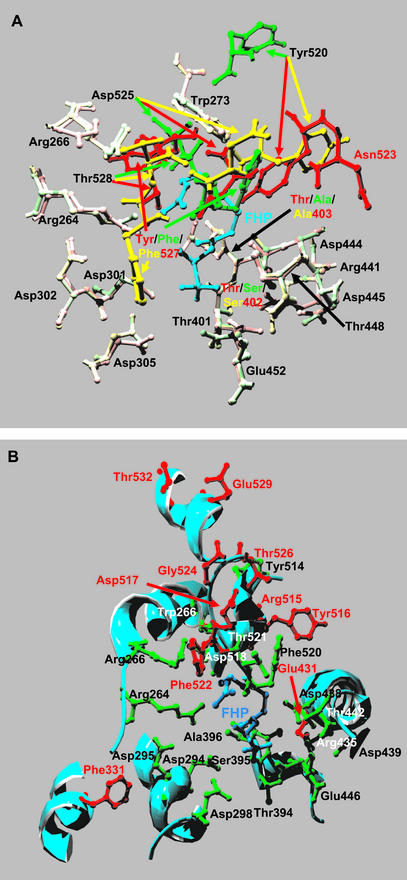

Modeling of GASs. Changes in Catalytic Amino Acids

The short and long chicory GAS (sharing 39% and 40% identity with TEAS, respectively) were modeled into the crystal structure of TEAS. The two models obtained in this way are quite similar and show a typical terpene synthase fold. Most of the amino acids indicated by Chappell and coworkers to be involved in catalysis are positioned almost identically in both the crystal and the two modeled GASs (Arg-264,266, Trp-273, Asp-301,302,305, Thr-401, Thr-402/Ser, Thr-403/Ala, Arg-441, Asp-444,445, Thr-448, and Glu-452; Fig. 7A). This would agree with the initial catalytic steps of both GASs and TEAS being identical. In contrast, quite a few differences occurred in amino acid identity and/or spatial location in the recently modeled δ-cadinene synthase, which were suggested to reflect the different enzyme mechanisms (Benedict et al., 2001). However, the modeled spatial location of Tyr-520 in the J-helix and Asp-525, Tyr-527/Phe, and Thr-528 in the J-K loop are significantly different not only, as could be expected, between TEAS and both GASs but also between the two GASs (Fig. 7A). The conservation of Tyr-520 in the GASs may undermine the conclusion of Rising et al. (2000) that Tyr-520 is required for the further cyclization of the enzyme-bound germacrene A to epi-aristolochene. However, the fact that the positional analogs of the TEAS Tyr-520 in the GASs are modeled to point away from the active site could again support their work. On the other hand, in view of the different spatial structure of the enzyme-bound germacrene carbocation recently reported by Rising et al. (2000), as compared with the original hypothesis (Starks et al., 1997), it is likely that Tyr-520 is not involved in the further cyclization of germacrene A to epi-aristolochene. As a consequence, the change of Tyr-527 to Phe or the different predicted spatial orientation of the latter in both GAS models (Fig. 7A) may be the change that is responsible for the termination of the reaction at germacrene A in the GASs.

Figure 7.

Molecular models of the two chicory GAS isoenzymes CiGASsh and CiGASlo. A, Detailed view of the active site residues of CiGASsh in (pale) green and CiGASlo in (pale) yellow and TEAS (T03714) in (pale) red. Pale colors indicate the amino acids with an identical position in the TEAS crystal structure and the GASs models. Bright colors indicate amino acids with differences in identity and/or spatial position that are discussed in the text. B, Detailed view of the active site residues of CiGASsh (green) and a selected number of amino acids (red) that have different physiochemical properties in the GASs compared with TEAS and that are discussed in the text. Molecular modeling was carried out using the Swiss-model service (http://www.expasy.ch/swissmod/; Peitsch, 1995, 1996; Guex and Peitsch, 1997) using the crystal structure of TEAS as a template. Models were rendered using POV-Ray for Windows (http://www.povray.org). Numbering follows the TEAS numbering (A) or the numbering of CiGASsh (B; also see Fig. 2).

Additional Changes in Amino Acids

To study the importance of any other amino acids in the catalysis of germacrene A formation, the two chicory GASs were aligned based on physiochemical properties. This alignment showed a very high conservation. About 98% of the deduced amino acids were grouped as having the same properties for the two GASs. When this was then compared with an alignment with TEAS, about 55 amino acid positions were classified as having similar properties in the GASs but different in TEAS. The model shows that many of these amino acids are located in loops and helices far away from the active site and, thus, probably do not affect product specificity (data not shown). However, Starks et al. (1997) hypothesized that amino acids in the layers surrounding the active site may also or even mainly influence the active site conformation and, hence, product specificity. For example, the analysis by Back and Chappell (1996) of the product formation of a number of chimeras of H. muticus vetispiradiene synthase and TEAS showed that the product specificity of these enzymes is located in domains that are, at least in part, not directly lining the active site. Using the physiochemical alignment of the GASs with TEAS, a number of amino acid changes could be pinpointed in the positional analogs of the domains identified by Back and Chappell. For example, the polar Ser-338 of TEAS that is located in the “epi-aristolochene domain” (Back and Chappell, 1996) is replaced by the apolar Phe-331 (Figs. 2 and 7B). The protein model predicts that the Phe is sticking out of the D-helix in the direction of the active site and close to the F-helix catalytic domain containing the three Asps (Asp-294, -295, and -298) involved in Mg2+ binding (Fig. 7B). In the “vetispiradiene domain” (Back and Chappell, 1996), the apolar Val-437 of TEAS is replaced by the polar Glu-431 (Figs. 2 and 7B). Glu-431 is located in the H2-helix close to Arg-435 and Thr-394, Ser-395, and Ala-396, which are located on the G2-helix of CiGASsh and, consequently, are close to the active site.

Finally, there are a number of changes in the J-K loop, which is proposed to form the lid on the active site (Fig. 7B). These changes are I521R515/K, N523Δ, L524D517, E531G524, V533T526, P536E529/D, and I539T532. The deletion of Asn-523 and the substitution of Leu-524 by the smaller amino acid Asp-517 may decrease the size of the active site pocket or change the orientation of amino acid side chains elsewhere in the loop as is predicted by the model, for example, for the Tyr-520 and Tyr-527 homologs of both GASs (Fig. 7A). In δ-cadinene synthase, the Leu-524 (or Asn-523) deletion and some amino acid substitutions, have also been suggested to play a role in active site size and/or amino acid orientation and, hence, product specificity (Benedict et al., 2001). In addition, a number of the changes in the J-K loop of the GASs mentioned above may have altered the electrostatic environment enough to permit the reaction to terminate at germacrene A.

CONCLUSION

Two GAS isoenzymes from chicory have been isolated and characterized. The genes exhibited a fairly low degree of homology, considering that the enzymes catalyze the formation of the same product. The comparison of the two GASs with crystallized TEAS enabled a number of amino acid residues that may be involved in the catalysis and product specificity of sesquiterpene synthases to be pinpointed. Crystallization and site-directed mutagenesis should show how important these pinpointed residues really are. In addition, the isolation of the GAS cDNAs may allow for the modification of sesquiterpenoid biosynthetic pathways in plants leading to, for example, sesquiterpene lactones. This offers exciting possibilities both for studies into the ecological significance of these compounds and also for the enhancement of the production of valuable, e.g. pharmacologically active, sesquiterpene lactones.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Material

Chicory (Cichorium intybus) heads, taproots, and seeds were obtained from Nunhems Zaden bv (Haelen, The Netherlands). Seedlings were obtained by germinating seeds at 20°C on moist filter paper in closed plastic containers in either light or darkness (to obtain etiolated seedlings). After incubation for 7 d, seedlings were frozen in liquid N2, ground, and stored at −80°C. For expression studies, taproots were separated into inner and outer tissue, and etiolated heads were separated into core and leaves. Green leaves were obtained by growing chicory taproots in potting compost in a greenhouse. After harvest, all samples were frozen, ground, and stored at −80°C for later analysis.

Isolation of Sesquiterpene Synthase Genes

Total RNA was isolated from etiolated chicory heads using the purescript RNA isolation kit (Biozym, Landgraaf, The Netherlands). Poly(A+) RNA was extracted from 20 μg of total RNA using 2 μg of poly(dT)25V oligonucleotides coupled to 1 mg of paramagnetic beads (Dynal A.S., Oslo). The reverse transcription reaction was carried out as described by Sambrook et al. (1989), and the cDNA was purified with the Wizard PCR Preps DNA purification system (Promega, Leiden, The Netherlands).

Based on comparison of sequences of terpenoid synthases, two degenerated primers were designed for two conserved regions: a sense primer (primer A), 5′-GAY GAR AAY GGI AAR TTY AAR GA-3′; and an anti-sense primer (primer B), 5′-CC RTA IGC RTC RAA IGT RTC RTC-3′ (Wallaart et al., 2001; Eurogentec, Seraing, Belgium). PCR was performed in a total volume of 50 μL containing 0.5 μm of the two primers, 0.2 mm dNTP, 1 unit of Super Taq polymerase/1× PCR buffer (HT Biotechnology LTD, Cambridge, UK), and 10 μL of cDNA. The reaction mixture was incubated in a thermocycler (Robocycler, Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) with 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 1.5 min of annealing at 42°C, and 1 min of elongation at 72°C for 40 cycles. Agarose gel electrophoresis revealed one fragment of approximately 550 bp. The PCR product was purified using the Wizard PCR Preps DNA purification system (Promega) and subcloned using the pGEMT system (Promega). Escherichia coli JM101 was transformed with this construct, and 12 individual transformants were sequenced, yielding two different sequences.

A cDNA library was constructed using the UniZap XR custom cDNA library service (Stratagene). For library screening, 200 ng of both PCR amplified probes were gel-purified, randomly labeled with [α-32P]dCTP, according to manufacturer's recommendation (Ready-To-Go DNA labeling beads [-dCTP], Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala), and used to screen replica filters of 104 plaques of the cDNA library plated on E. coli XL1-Blue MRF′ (Stratagene). The plaque lifting and hybridization were carried out according to standard protocols (Sambrook et al., 1989). Positive clones were isolated using a second and third round of hybridization. In vivo excision of the pBluescript phagemid from the Uni-Zap vector was performed according to manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene). Two groups of positive clones were obtained that could be distinguished using restriction enzymes and PCR.

cDNAs were sequenced using the Eurogentec Publication Service. Sequences were compared with sequences in GenBank using BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast). Sequences were analyzed and aligned using the DNAStar (Madison, WI), ClustalX, and Genedoc software. Numbering of amino acids mostly follows that for TEAS (T03714; Starks et al., 1997). Genedoc was also used to align sequences based on physiochemical properties. The Genedoc software uses the grouping of Taylor (1986) with minor modifications (Genedoc reference manual). Phylogenetic trees were constructed with the neighbor joining method using bootstrapping with the ClustalX and Treeview software. Molecular modeling was carried out using the Swiss-model service (http://www.expasy.ch/swissmod/; Peitsch, 1995, 1996; Guex and Peitsch, 1997). Models were rendered using POV-Ray for Windows (http://www.povray.org).

Expression of the Isolated cDNAs in E. coli

For functional expression, the cDNA clones were subcloned in frame into the expression vector pET 11d (Stratagene). To introduce suitable restriction sites for subcloning, cDNA 1 (“short”) was amplified using the sense primer 5′-CCT TCA AGC CAT GGC AGC AGT TG-3′ (introducing an NcoI site at the start codon ATG) and anti-sense primer 5′-TTG TAA TAG GAT CCA CTA TAG G-3′ (introducing a BamHI site between the stop codon TGA and the poly[A] tail in the Bluescript vector). cDNA 2 (“long”) was amplified by PCR with the sense primer 5′-CAA TCC GAA CCA TGG CTC TCG TT-3′ (introducing an NcoI site at the start codon ATG) and anti-sense primer 5′-CAC CAA ATG GAT CCA AAT TCG C-3′ (introducing a BamHI site between the stop codon TGA and the poly[A] tail).

The PCR reactions were performed under standard conditions as described above but using Pwo polymerase (Roche Diagnostics NL bv, Almere, The Netherlands). After digestion with BamHI and NcoI, the PCR product and the expression vector pET 11d were gel purified and ligated. The two constructs and pET 11d without an insert (as negative control) were transformed to E. coli BL 21 (DE3; Stratagene), and grown overnight on Luria-Bertani agar plates supplemented with ampicillin at 37°C. The colonies on the agar plates were resuspended in Luria-Bertani medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL) and 0.25 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and grown to o.d. 0.5.

Identification of Products of Enzymes Expressed in E. coli

After induction, the E. coli cells were harvested by centrifugation for 8 min at 2,000g and resuspended in 1.2 mL of buffer containing 15 mm Mopso (pH 7.0), 10% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm sodium ascorbate, and 2 mm dithiothreitol (DTT). The resuspended cells were sonicated on ice for 4 min (5 s on, 30 s off). After centrifugation for 5 min at 4°C (14,000 rpm), the supernatant was diluted 1:1 with the same buffer but containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20, and 20 μm [3H]FDP was added to 1 mL of this enzyme preparation. After the addition of a 1-mL redistilled pentane overlay, the tubes were carefully mixed and incubated for 1 h at 30°C. After the assay, the tubes were mixed, and the organic layer was removed and passed over a short column of aluminum oxide overlaid with anhydrous Na2SO4. The assay was re-extracted with 1 mL of pentane:diethyl ether (80:20, v/v), which was also passed over the aluminum oxide column, and the column washed with 1.5 mL of pentane:diethyl ether (80:20, v/v). The column was then moved to another tube, and the assay was re-extracted with 1 mL of diethyl ether, which was also passed over the column. Finally, the column was washed with another 1.5 mL of diethyl ether. The extracts were analyzed using radio-GLC on a Carlo-Erba 4160 Series gas chromatograph equipped with a RAGA-90 radioactivity detector (Raytest, Straubenhardt, Germany) and GC-MS using an HP 5890 series II gas chromatograph equipped with an HP-5MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness) and HP 5972A mass selective detector (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA) as described previously (Bouwmeester et al., 1999b).

The absolute configuration of the germacrene A produced by the two encoded proteins was assessed using GC-MS equipped with an enantioselective column as described by de Kraker et al. (1998).

Expression Analysis

Expression of the isolated cDNAs was analyzed in chicory taproots, etiolated heads, green leaves, and green and etiolated seedlings. RNA was isolated using the Wizard system (SV Total RNA Isolation System, Promega) according to the procedure recommended by the manufacturer. Of each sample, 2 μg of total RNA, treated with dimethyl sulfoxide glyoxal, was separated on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel and blotted onto Hybond-N+ nylon membrane using 7.5 mm NaOH as described by Sambrook et al. (1989). To fix the RNA, the membrane was exposed to UV light (254 nm). Prehybridization (at 65°C) and hybridization were carried out according to Sambrook et al. (1989) in a solution containing 2× SSC, 5× Denhardt's solution, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, and 0.2 μg/mL herring sperm DNA. The probes used for hybridization were generated using the Ready-To-Go system according to the procedure recommended by the manufacturer (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) and using [32P]dCTP (ICN Biochemicals bv, Zoetermeer, The Netherlands) and (gel-) purified PCR fragments of the genes to be analyzed as templates. After hybridization, the blots were washed under highest stringency conditions (at 68°C with 0.1× SSPE + 0.1% [w/v] SDS) and exposed to a P Imaging Plate (Fuji Photo Film, Tokyo).

Partial Purification of GASs

From Chicory

Chicory heads were cut into small pieces, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and ground to a fine powder using a cooled mortar and pestle. One gram of this powder was homogenized in 10 mL of buffer containing 25 mm Mopso (pH 7.0), 20% (v/v) glycerol, 25 mm sodium ascorbate, 25 mm NaHSO3, 10 mm MgCl2 and 5 mm DTT and slurried with 0.5 g of polyvinylpolypyrrolidone and a spatula tip of purified sea sand. To the homogenate, 0.5 g of polystyrene resin (Amberlite XAD-4, Serva, Garden City Park, NY) was added, and the slurry was stirred carefully for 10 min and then filtered through cheesecloth. The filtrate was centrifuged at 20,000g for 20 min (pellet discarded) and then at 100,000g for 90 min. The 100,000g supernatant was loaded on a 10- × 2.5-cm column of Q-Sepharose (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech) previously equilibrated with buffer containing 15 mm Mopso (pH 7.0), 10% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm DTT (buffer A). The column was washed with buffer A and eluted with a 0 to 2.0 m KCl gradient in buffer A. For determination of enzyme activities, 20 μL of the 2.0-ml fractions was diluted 5-fold in an Eppendorf tube with buffer A, and 20 μm [3H]FDP was added. The reaction mixture was overlaid with 1 mL of hexane to trap volatile products, and the contents were mixed. After incubation for 30 min at 30°C, the vials were mixed and centrifuged to separate phases. A portion of the hexane phase (750 μL) was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube containing 40 mg of silica gel, and, after mixing and centrifugation, 500 μL of the hexane layer was removed for liquid scintillation counting in 4.5 mL of Ultima Gold cocktail (Packard Bioscience, Groningen, The Netherlands). The combined active fractions were desalted to buffer A, and 1.0 mL of this enzyme preparation was applied to a MonoQ FPLC column (HR5/5, Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech), previously equilibrated with buffer A containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20. The column was eluted with a gradient of 0 to 600 mm KCl in the same buffer, and the activity was determined as described above. Product identity was determined using radio-GLC as described above for the heterologous proteins, but now 0.5 mL of each of the two most active fractions was diluted 2-fold with buffer A.

From E. coli Expressing the Chicory GASs

After induction as described above, the E. coli cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 200 μL of buffer A and stored at −80°C until use. After thawing, the cells were sonicated on ice during 4 min (5 s on, 30 s off). After centrifugation, the supernatant was diluted 1:1 with buffer A containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 and applied to the MonoQ FPLC column. Proteins were eluted, and activities of fractions and product identity were determined as described above for the plant proteins. Enzyme kinetics were determined as described previously (Bouwmeester et al., 1999a).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jos Suelmann and Paul Heuvelmans of Nunhems Zaden bv for gifts of chicory seeds and plant material; Roger Peeters, Luc Stevens, and Wilco Jordi for helpful suggestions; Robert Hall, Maurice Franssen, Asaph Aharoni, and Jules Beekwilder for helpful comments on the manuscript; Ruud de Maagd for his help with protein modeling; and Wilfried König for his gift of germacrene A and (+)- and (−)-β-elemene.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by Nunhems Zaden BV and the R&D Subsidy for Technological Co-operation (project BTS 97102; to H.J.B., F.W.A.V., and J.K.).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/doi/10.1104/pp.001024.

LITERATURE CITED

- Back K, Chappell J. Identifying functional domains within terpene cyclases using a domain swapping strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6841–6845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict CR, Lu J-L, Pettigrew DW, Liu J, Stipanovic RD, Williams HJ. The cyclization of farnesyl diphosphate and nerolidyl diphosphate by a purified recombinant δ-cadinene synthase. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1754–1765. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann J, Martin D, Oldham NJ, Gershenzon J. Terpenoid secondary metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana: cDNA cloning, characterization and functional expression of a myrcene/(E)-β-ocimene synthase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;375:261–269. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann J, Meyer-Gauen G, Croteau R. Plant terpenoid synthases: molecular biology and phylogenetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:4126–4133. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester HJ, Verstappen FWA, Posthumus MA, Dicke M. Spider mite-induced (3S)-(E)-nerolidol synthase activity in cucumber and lima bean: the first dedicated step in acyclic C11-homoterpene biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 1999a;121:173–180. doi: 10.1104/pp.121.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmeester HJ, Wallaart TE, Janssen MHA, van Loo B, Jansen BJM, Posthumus MA, Schmidt CO, de Kraker J-W, König WA, Franssen MCR. Amorpha-4,11-diene synthase catalyzes the first probable step in artemisinin biosynthesis. Phytochemistry. 1999b;52:843–854. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(99)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kraker J-W, Franssen MCR, de Groot Ae, König WA, Bouwmeester HJ. (+)-Germacrene A biosynthesis: the committed step in the biosynthesis of sesquiterpene lactones in chicory. Plant Physiol. 1998;117:1381–1392. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kraker J-W, Franssen MCR, de Groot Ae, König WA, Bouwmeester HJ. Biosynthesis of germacrene A carboxylic acid in chicory roots: demonstration of a cytochrome P450 (+)-germacrene a hydroxylase and NADP+-dependent sesquiterpenoid dehydrogenase(s) involved in sesquiterpene lactone biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:1930–1940. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.4.1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Kraker J-W, Franssen MCR, Joerink M, de Groot Ae, Bouwmeester HJ. Biosynthesis of costunolide, dihydrocostunolide, and leucodin. Demonstration of cytochrome P450-catalyzed formation of the lactone ring present in sesquiterpene lactones of chicory. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:257–268. doi: 10.1104/pp.010957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: an environment for comparative protein modelling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann K. Übersicht über nichtessentielle Inhaltsstoffe der Gemüsearten: III. Möhren, Sellerie, Pastinaken, Rote Rüben, Spinat, Salat, Endivien, Treibzichorie, Rhabarber und Artischocken. Z Lebensm Unters Forsch. 1978;167:262–273. doi: 10.1007/BF01135600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewlett MJ, Begley MJ, Groenewegen WA, Heptinstall S, Knight DW, May J, Salan U, Toplis D. Sesquiterpene lactones from feverfew, Tanacetum parthenium: isolation, structural revision, activity against human blood platelet function and implications for migraine therapy. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans I. 1996;16:1979–1986. [Google Scholar]

- Monde K, Oya T, Shirata A, Takasugi M. A guaianolide phytoalexin, cichoralexin, from Cichorium intybus. Phytochemistry. 1990;29:3449–3451. [Google Scholar]

- Nishino C, Bowers WS, Montgomery ME, Nault LR, Nielson MW. Alarm pheromone of the spotted alfalfa aphid, Therioaphis maculataBuckton (Homoptera: Aphididae) J Chem Ecol. 1977;3:349–357. [Google Scholar]

- Peitsch MC. Protein modeling by e-mail. BioTechnology. 1995;13:658–660. [Google Scholar]

- Peitsch MC. ProMod and Swiss-Model: internet-based tools for automated comparitive protein modelling. Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:274–279. doi: 10.1042/bst0240274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picman AK. Biological activities of sesquiterpene lactones. Biochem Syst Ecol. 1986;14:255–281. [Google Scholar]

- Price KR, DuPont MS, Shepherd R, Chan HW-S, Fenwick GR. Relationship between the chemical and sensory properties of exotic salad crops: colored lettuce (Lactuca sativa) and chicory (Cichorium intybus) J Sci Food Agric. 1990;53:185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Rees BS, Harborne JB. The role of sesquiterpene lactones and phenolics in the chemical defense of the chicory plant. Phytochemistry. 1985;24:2225–2231. [Google Scholar]

- Rising KA, Starks CM, Noel JP, Chappell J. Demonstration of germacrene A as an intermediate in 5-epi-aristolochene synthase catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:1861–1866. [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Ed 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. pp. 7.40–7.50. [Google Scholar]

- Starks CM, Back K, Chappell J, Noel JP. Structural basis for cyclic terpene biosynthesis by tobacco 5-epi-aristolochene synthase. Science. 1997;277:1815–1819. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5333.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor WR. The classification of amino acid conservation. J Theor Biol. 1986;119:205–218. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(86)80075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teisseire PJ. Chemistry of Fragrant Substances. New York: VCH Publishers Inc.; 1994. pp. 193–289. [Google Scholar]

- Trapp SC, Croteau RB. Genomic organization of plant terpene synthases and molecular evolutionary implications. Genetics. 2001;158:811–832. doi: 10.1093/genetics/158.2.811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Beek TA, Maas P, King BM, Leclercq E, Voragen AGJ, de Groot Ae. Bitter sesquiterpene lactones from chicory roots. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38:1035–1038. [Google Scholar]

- van der Hoeven RS, Monforte AJ, Breeden D, Tanksley SD, Steffens JC. Genetic control and evolution of sesquiterpene biosynthesis in Lycopersicon esculentum and L. hirsutum. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2283–2294. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallaart TE, Bouwmeester HJ, Hille J, Poppinga L, Maijers NCA. Amorpha-4,11-diene synthase: cloning and functional expression of a key enzyme in the biosynthetic pathway of the novel antimalarial drug artemisinin. Planta. 2001;212:460–465. doi: 10.1007/s004250000428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead IM, Threlfall DR, Ewing DE. 5-Epi-aristolochene is a common precursor of the sesquiterpenoid phytoalexins capsidiol and debneyol. Phytochemistry. 1989;28:775–779. [Google Scholar]