Abstract

The neurodegenerative disorder FRDA (Friedreich's ataxia) results from a deficiency in frataxin, a putative iron chaperone, and is due to the presence of a high number of GAA repeats in the coding regions of both alleles of the frataxin gene, which impair protein expression. However, some FRDA patients are heterozygous for this triplet expansion and contain a deleterious point mutation on the other allele. In the present study, we investigated whether two particular FRDA-associated frataxin mutants, I154F and W155R, result in unfolded protein as a consequence of a severe structural modification. A detailed comparison of the conformational properties of the wild-type and mutant proteins combining biophysical and biochemical methodologies was undertaken. We show that the FRDA mutants retain the native fold under physiological conditions, but are differentially destabilized as reflected both by their reduced thermodynamic stability and a higher tendency towards proteolytic digestion. The I154F mutant has the strongest effect on fold stability as expected from the fact that the mutated residue contributes to the hydrophobic core formation. Functionally, the iron-binding properties of the mutant frataxins are found to be partly impaired. The apparently paradoxical situation of having clinically aggressive frataxin variants which are folded and are only significantly less stable than the wild-type form in a given adverse physiological stress condition is discussed and contextualized in terms of a mechanism determining the pathology of FRDA heterozygous.

Keywords: frataxin, Friedreich's ataxia (FRDA), iron-binding protein, protein folding, trinucleotide expansion

Abbreviations: FRDA, Friedreich's ataxia; GdmCl, guanidinium chloride; GuSCN, guanidine thiocyanate; TEV, tobacco etch virus; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid

INTRODUCTION

The possibility of identifying genetic mutations causing human diseases is a revolutionary achievement accomplished only within the last 3–4 decades, which has opened new avenues towards our understanding of pathologies. We now know that even a single amino acid mismatch from the wild-type protein sequence may result in major metabolic consequences in an organism thus often leading to severe pathologies. Understanding which effect a point mutation has is therefore an important topic not only essential for our basic knowledge of how proteins fold, but also with direct applications to molecular medicine.

We have recently become interested in single point mutations observed in FRDA (Friedreich's ataxia), an autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disease linked to oxidative stress and caused by reduced levels of a small mitochondrial protein, frataxin, encoded by a gene mapped to chromosomal locus 9q13 [1,2]. Although the exact function of frataxin is still unknown, increasing evidence suggests a role of the protein in iron–sulfur cluster formation [3–9]. The majority of FRDA patients are homozygous for an intronic expansion of a GAA trinucleotide repeat within the frataxin gene [10]. The abnormal triplet expansion does not completely abolish frataxin expression, and a shorter magnitude of the expansion correlates with the late onset of the disease. However, a few FRDA patients (approx. 4%) are heterozygous, containing an expanded repeat in one allele and a deleterious point mutation in the other [10]. These DNA alterations can lead either to protein truncation or to missense modifications in the mature region of the protein. The latter are particularly interesting as they have different impacts on disease expression: whereas some mutations lead to the normal phenotype of the disease, others result in atypical milder clinical presentations of the pathology. At the present time, at least 15 missense frataxin point mutations have been described in FRDA patients [10]. Reports on these mutations [10] indicate that they do not interfere with splicing and the fact that some compound heterozygous individuals have atypical phenotypic expressions of the disease is suggestive of the cellular presence of frataxin with a partly reduced function [10,11]. Although mapping these mutations on to the available three-dimensional structures of frataxin [12–15] can provide a framework for predicting its effect on the protein structure, the exact impact of these clinically relevant missense mutations on the folding pathway of frataxin remains to be experimentally and quantitatively addressed.

In the present paper, we report our studies on the structural stability and folding properties of human frataxin, and on two mutant variants comprising clinically relevant point mutations, I154F and W155R. These modifications involve highly conserved amino acids and are located in structurally distinct regions of the protein [14]. Previous studies have suggested that the two mutations represent two extreme possibilities [10,13]. The first one, I154F, constitutes the most common clinically occurring mutation and affects a residue which is part of the protein core. This mutant is therefore expected to directly affect the stability of the protein fold and should be structurally important. The second mutation involves instead the conserved Trp155, which is part of an invariant surface in the exposed region of a β-sheet. The aromatic ring of Trp155 is fully solvent-exposed, suggesting a role of this residue in interaction with a partner. The mutation is expected to be functionally important, since conservation of surface residues usually implies that they are involved directly in protein function. Both mutations lead to aggressive phenotypic development of the ataxia [10,13]. In a preliminary report, we showed that both of these mutants are folded [13]. Although this result constitutes little surprise for W155R, the fact that the clinical mutation I154F, which in vivo leads to a severe expression of the pathology, results in a protein which is essentially folded under physiological conditions may seem paradoxical in respect to disease expression.

To understand further this apparent paradox, we have extended and complemented previous preliminary data by carrying out an extensive study of the thermodynamic stability of frataxin and its variants using a number of complementary biochemical and biophysical techniques. By exploring different chemical denaturants and experimental conditions, we find that both mutations affect the thermodynamic stability of the proteins, but to a very different extent so that the destabilization does not affect the fold of the proteins at physiological temperatures or pH. We show that the structural dynamics of mutant frataxin variants is altered in respect to the wild-type protein, resulting in a partly destabilized conformation, more prone to proteolytic processing. Furthermore, both proteins retain partly their iron-binding properties. This suggests, in particular, that Trp155 and the surface around it are implicated in a function distinct from iron binding. On the basis of our results, we suggest a mechanism to explain the strong pathology associated with I145F. Our study may therefore contribute to a molecular understanding of the frataxin functions and ultimately of its role in FRDA pathology.

EXPERIMENTAL

Chemicals

All reagents were of the highest purity grade commercially available. The chemical denaturant GuSCN (guanidine thiocyanate) was purchased from Promega. Stock solutions were prepared in different buffers, and the concentration was determined by its density. GdmCl (guanidinium chloride) was obtained from Sigma and the accurate concentration of the stock solutions in different buffers was confirmed by refractive index measurements.

Gene expression and protein purification

The constructs [from the truncated frataxin (amino acids 91–210), hereon called simply Hfra-(91–210), and mutant forms] were expressed in Escherichia coli (competent BLC21 DE3 cells from Novagen) as fusion proteins with a His6 and a GST (glutathione S-transferase) tag with cleavage site for TEV (tobacco etch virus) or PreScission protease as described previously [13,16]. Briefly, the wild-type and the two frataxin variants were purified to homogeneity, after the cells were grown in LB (Luria–Bertani) medium with 30 μg/ml kanamycin. The soluble cell extract was applied on a glutathione–Sepharose column (10 ml) previously equilibrated with PBS, and eluted with 30 ml of PBS, after which TEV was added (2 ml of 25 μM TEV per litre of cell culture). The column was closed and left overnight at 4 °C. The purified protein was eluted by washing the column with PBS. The tags as well as TEV remained bound and were subsequently eluted with reduced glutathione. Protein concentration was determined using the molecular absorption coefficient ϵ280=21030 M−1·cm−1. Both mutants were found to be stable in solution, although susceptible to precipitation upon slow freezing; however, thawed proteins that had been fast-frozen retained their spectroscopic properties and melting temperatures.

Spectroscopic methods

UV/visible spectra were recorded at room temperature (25 °C) in a Shimadzu UVPC-1601 spectrometer with cell stirring. Fluorescence spectroscopy was performed using a Cary Varian Eclipse instrument (λex=280 nm; λem=340 nm; slitex=5 nm; slitem=10 nm, unless otherwise noted) with cell stirring and Peltier temperature control. Far-UV CD spectra were recorded typically at 0.2 nm resolution on a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter fitted with a cell holder thermostatically controlled with a Peltier.

Chemical denaturation

The denaturation curves were measured using the dilution method, and two solutions with the same protein concentration were prepared: one with no denaturation agent and the other with a high concentration of denaturation agent. These were combined in different proportions yielding different denaturant concentrations. After mixing, the solutions were left to equilibrate for 2 h. Transitions curves were determined plotting the average emission wavelength against denaturant concentrations, correcting for the pre- and post-transitions [17–19]. A non-linear least-squares analysis was used to fit the data to a two-state model described by eqn (1) [19]:

|

(1) |

where y represents the average emission wavelength observed for a given denaturant concentration, [D], yf and yu are the intercepts and mf and mu are the slopes of the pre- and post-transition baselines, [D]1/2 is the denaturant concentration at the curve midpoint and m is from eqn (2):

|

(2) |

Thermal denaturation

Thermal unfolding was followed by monitoring the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (λex=280 nm; λem=340 nm; slitex=5 nm; slitem=10 nm) and the ellipticity (Δϵmrw at 222 nm) variations. It has been demonstrated previously [20] that identical melting temperatures are obtained for frataxin by both CD and fluorescence spectroscopies, thus ruling out artefacts resulting from changes of fluorescence quantum yield with temperature. Furthermore, differential scanning calorimetry experiments confirmed melting temperatures (results not shown). In all of the experiments, a heating rate of 1 °C/min was used, and the temperature was changed from 20 to 90 °C. Data were analysed according to a two-state model described by eqn (3):

|

(3) |

where y is the spectroscopic signal observed, mf and mu are the slopes of the pre- and post-transition baselines, yf and yu correspond to the value of y for folded and unfolded forms, Tm is the midpoint of the thermal unfolding curve, and ΔHm is the enthalpy change for unfolding at Tm [19]. The fits to the unfolding transitions were made using Origin (MicroCal). For pH variations, the buffers used were 30 mM acetate (pH 4.9), 40 mM phosphate (pH 6.0, 7.9 and 11.6), 10 mM Hepes (pH 7.0) and 40 mM glycine (pH 8.9 and 9.7). The reversibility of the reaction was investigated by downward temperature ramps, as well as repetition of the upward ramps after cooling the sample to 25 °C.

Fluorescence quenching

Quenching experiments were preformed using a neutral quencher, acrylamide (Bio-Rad), and an ionic quencher, KI (Fluka). The samples were excited at 295 nm in order to ensure that the light was absorbed almost entirely by tryptophan groups and the fluorescence intensity decrease at 340 nm was followed. Results were analysed according to the Stern–Volmer equation (eqn 4):

|

(4) |

where F0 and F are the fluorescence intensities in the absence and presence of quencher respectively, KSV is the collisional quenching constant and [Q] is the quencher concentration [21].

Trypsin limited proteolysis

Frataxins were incubated with trypsin (bovine pancreas trypsin, sequencing grade; Sigma) at 37 °C in 0.1 M Tris/HCl, pH 8.5, in a 100-fold excess over the protease. Aliquots (approx. 0.5 nmol of protein) were sampled at different incubation periods and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 0.2% (v/v) TFA (trifluoroacetic acid). The products of the proteolysis reaction were analysed by reverse-phase HPLC (Waters Alliance System 2695), using a C18 column 150 mm×3.9 mm (DeltaPak, Waters) run at a flow rate of 0.5 ml·min−1, monitoring the absorbance at 214 nm. The peptidic profiles were obtained running a three-step gradient from (A) 0.1% (v/v) TFA to (B) 80% (v/v) acetonitrile+0.1% (v/v) TFA: 0–37% (in 65 min), 37–75% (in 30 min) and 75–100% (in 20 min). The column was regenerated with 0.1% (v/v) TFA.

RESULTS

Thermodynamics of frataxin chemical and thermal unfolding

To evaluate the effect of the introduced clinical mutations on the human frataxin fold, the chemical and thermal unfolding reactions of human frataxin were investigated in detail. Frataxin unfolding can be monitored either by fluorescence or by far-UV CD spectroscopy (Figure 1); in the present study, intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence changes were routinely used to monitor unfolding transitions (see the Experimental section). Under most denaturation conditions tested, frataxin unfolding was found to be highly reversible. Hfra-(91–210) exhibits considerable stability over the physiological pH range: its thermal unfolding transition is reversible and essentially invariant between pH 6 and 9 (Table 1). However, below pH 5, which is the isoelectric point of Hfra-(91–210), as well as at higher pH values, an increasing extent of irreversibility was observed as a result of protein aggregation. At lower pH values, this is expected considering the decreased solubility of the unfolded form of a protein near its isoelectric point [19,22].

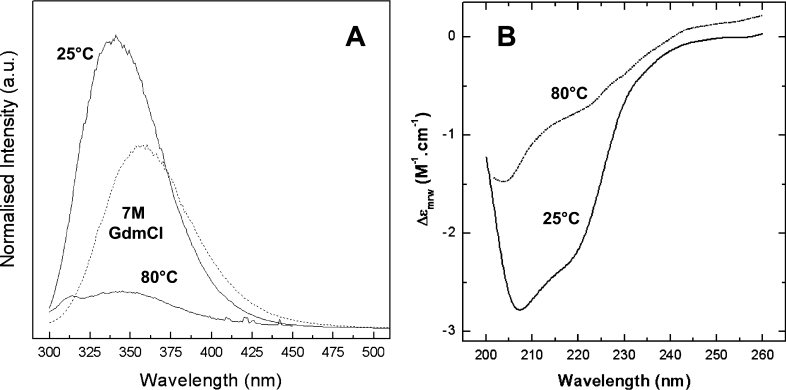

Figure 1. Spectroscopic characterization of wild-type Hfra-(91–210) in different conformational states.

(A) Fluorescence spectroscopy. Emission spectra of the native form (25 °C), and the chemically (7 M GdmCl) and thermally (80 °C) denaturated forms. (B) Far-UV CD spectroscopy. Spectra of the native and thermally denaturated forms. a.u., arbitrary units.

Table 1. Parameters for Hfra thermal denaturation as a function of pH.

| pH | Tm (°C) | ΔHm (kJ·mol−1) | ΔTm (°C) | Refolding (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.9 | 59.0±0.1 | 275.1±1.7 | −7.3±0.1 | 20 |

| 6.0 | 65.4±0.2 | 371.8±2.1 | −0.9±0.3 | 80 |

| 7.0 | 62.5±0.2 | 250.4±1.3 | −3.8±0.3 | 95 |

| 7.9 | 66.3±0.1 | 373.5±1.7 | – | 100 |

| 8.9 | 62.1±0.2 | 362.2±3.3 | −4.2±0.3 | 100 |

| 9.7 | 59.0±0.1 | 282.2±1.3 | −7.3±0.1 | 20 |

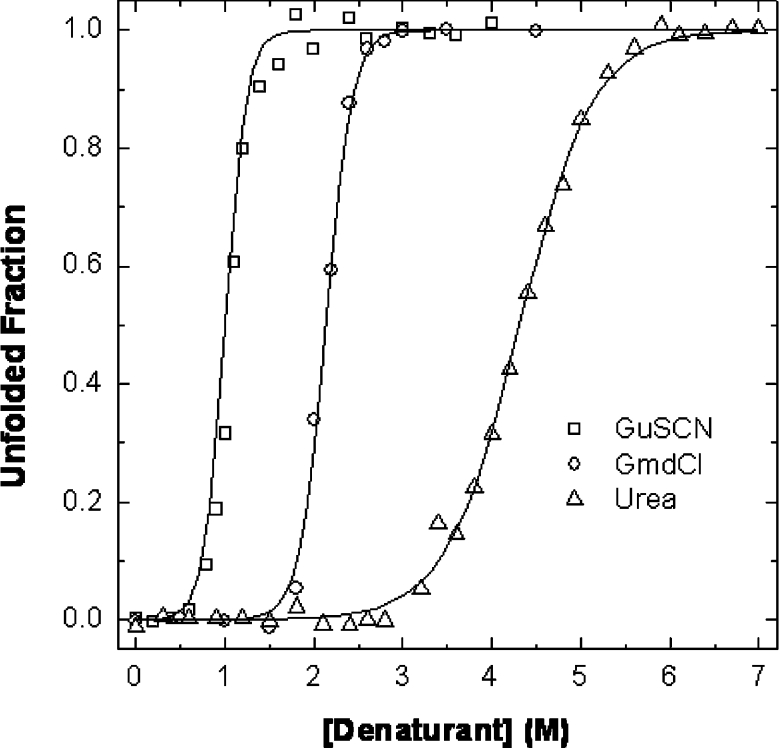

Chemical denaturation experiments were performed at pH 7.9 using urea, GdmCl and GuSCN as denaturants. The obtained curves were analysed assuming a two-state mechanism, and the unfolded fraction was plotted as a function of denaturant concentration; from the data in the transition region, and using the linear extrapolation model, the thermodynamic parameters ΔGH2O and m were determined (Figure 2 and Table 2). Frataxin conformational stability ranges from 23.8 to 35.6 kJ·mol−1 (5.7–8.5 kcal·mol−1).

Figure 2. Chemical denaturation curves for Hfra-(91–210) at pH 7.9.

Hfra-(91–210) typical denaturation curves with (○) GdmCl, (□) GuSCN and (△) urea. Lines represent fits to the two state model; see Table 2 for parameters.

Table 2. Parameters for the chemical denaturation of wild-type hfra, pH 7.9.

| Denaturant | [D]1/2 (M) | m (kJ·mol−1·M−1) | ΔGH2O (kJ·mol−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GuSCN | 1.1 | 22.4±1.4 | 24.6±1.7 |

| GdmCl | 2.1 | 16.8±1.4 | 35.3±2.1 |

| Urea | 4.3 | 5.7±0.2 | 24.5±1.3 |

Conformational dynamics of mutant frataxins

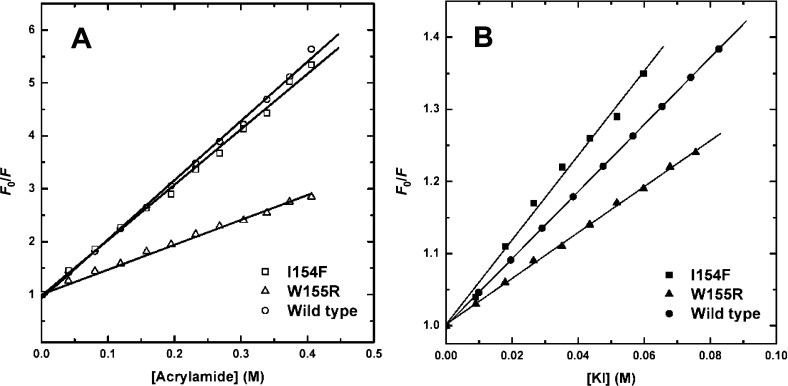

The impact of the clinical mutations on the frataxin fold and dynamics was evaluated from fluorescence quenching studies. Fluorescence quenching experiments were performed at 25 °C, using acrylamide and iodide (Figure 3 and Table 3). Acrylamide is a neutral quencher molecule, more able to access the protein interior and quench buried residues, whereas iodide is negatively charged. The Stern–Volmer constant for the I154F mutant Hfra-(91–210) is comparable with that of the wild-type for both quenchers, which shows that this structural core mutation does not result in protein misfolding. With respect to the W155R Hfra-(91–210) variant, a lower Stern–Volmer constant was determined, in agreement with the fact that, since the two remaining tryptophan residues are not superficial, the protein matrix will strongly slow down the penetration of the quencher molecules. For all frataxins studied, the accessibility of the tryptophan residues is increased in the presence of GdmCl, corresponding to a disrupted tertiary structure. Thus quenching experiments show that, under physiological conditions, the mutant frataxins have a globally stable wild-type-like fold and breathing dynamics.

Figure 3. Stern–Volmer plots of acrylamide and iodide quenching of frataxin tryptophan fluorescence.

Plots of F0/F against concentration of acrylamide (A) and iodide (B) for the native wild type Hfra-(91–210) (○), W155R Hfra-(91–210) (△) and I154F Hfra-(91–210) (□). See Table 3 for parameters.

Table 3. Effect of FRDA mutations on quencher accessibility and Stern–Volmer constants using different quenchers.

| KSV (M−1) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Protein | Acrylamide | KI |

| Wild-type | 11.2±0.2 | 5.0±0.2 |

| W155R | 4.5±0.1 | 3.2±0.1 |

| I154F | 10.5±0.2 | 5.9±0.2 |

Limited proteolysis experiments evidence destabilization of mutant frataxin forms

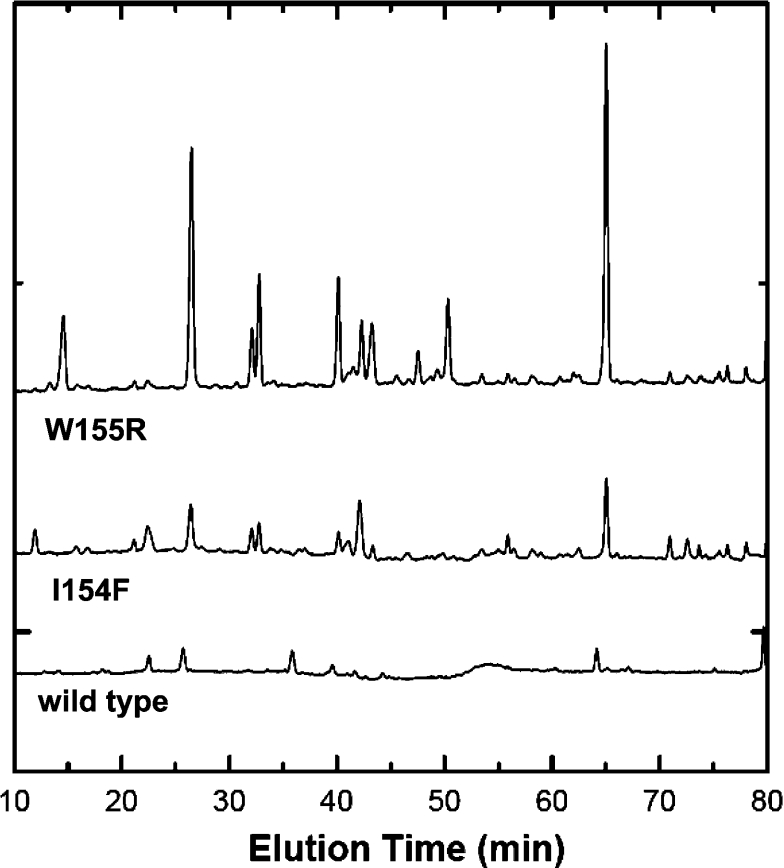

The conformational differences between wild-type and the mutant frataxin forms were accessed by monitoring the progression of trypsin-mediated proteolysis. Trypsin was selected for this comparative mapping as it cleaves with high specificity at the C-terminal side of lysine and arginine, unless the following position is occupied by a proline residue [23]. Inspection of the protein sequence identifies 11 possible digestion sites for the wild-type and I154F proteins, and an additional one for the W155R mutant, as a result of the inserted arginine residue. A comparison of these limited proteolysis experiments allows evaluation of the degree of destabilization of the mutant forms with respect to the native protein, since we expect that a destabilized fold will have more accessible cleavage sites and undergo faster proteolysis. The obtained peptide maps show clearly that both mutant frataxins are destabilized with respect to the wild-type protein, as is evident by the appearance of a substantially higher number of peptides during the same incubation period (Figure 4). This observation indicates that the clinical mutant frataxins under study contain partly destabilized regions which make them more prone to degradation.

Figure 4. Peptide maps resulting from partial tryptic digestions.

Wild-type and mutant variants (I154F and W155R) after being incubated with trypsin for 100 min at 37 °C.

Iron-binding properties of clinical frataxin variants are impaired by protein destabilization

Iron binding was also investigated as this aspect may provide useful insights into the biological impact of the mutated variants, since frataxin has been proposed to act as a cellular iron chaperone. Frataxin is known to be able to bind six or seven irons per molecule, albeit with low affinity [7,24]. The FRDA-associated mutant frataxins were investigated with respect to their ability to bind iron, as well as the wild-type protein, which was used as a positive control. Iron binding monitored by fluorescence spectroscopy according to a procedure reported previously [7] showed that progressive iron binding destabilizes the mutants, resulting in protein precipitation. Although this occurs both with Fe(II) and Fe(III), and under pH-controlled conditions, the ferric ion seems to have a more destabilizing effect and precipitation is observed above an iron/frataxin ratio of 2:1. Concerning ferrous ion binding, precipitation was only observed at iron/frataxin ratios ranging from 5:1 to 7:1. Thus, although none of these FRDA-associated mutations is directly involved in the proposed iron-binding region [24,25], its binding may have a negative functional impact as it probably induces structural modifications which destabilize the frataxin fold, leading to the formation of precipitates. In any case, iron-mediated colloidal precipitation of the mutant frataxins cannot be ruled out at this stage.

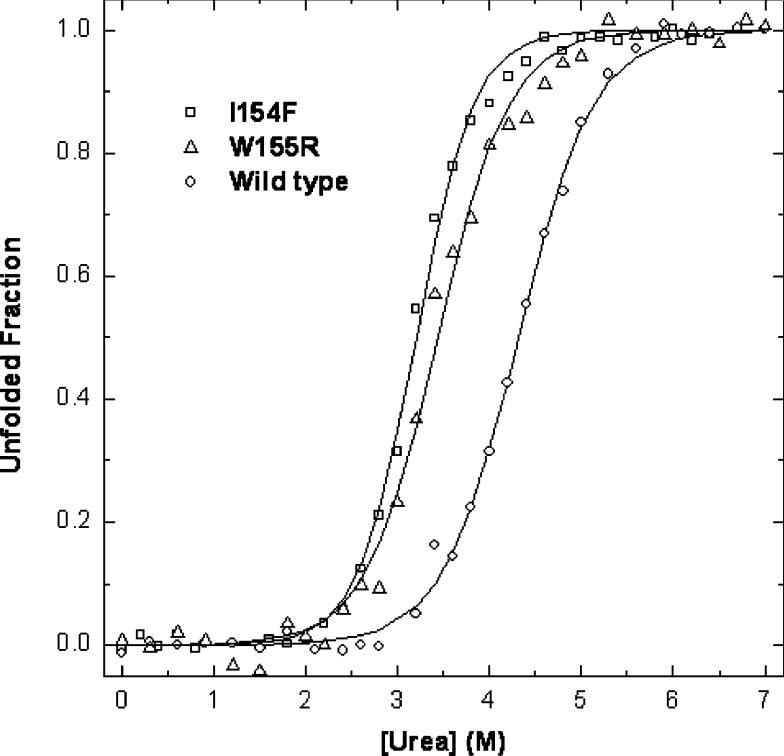

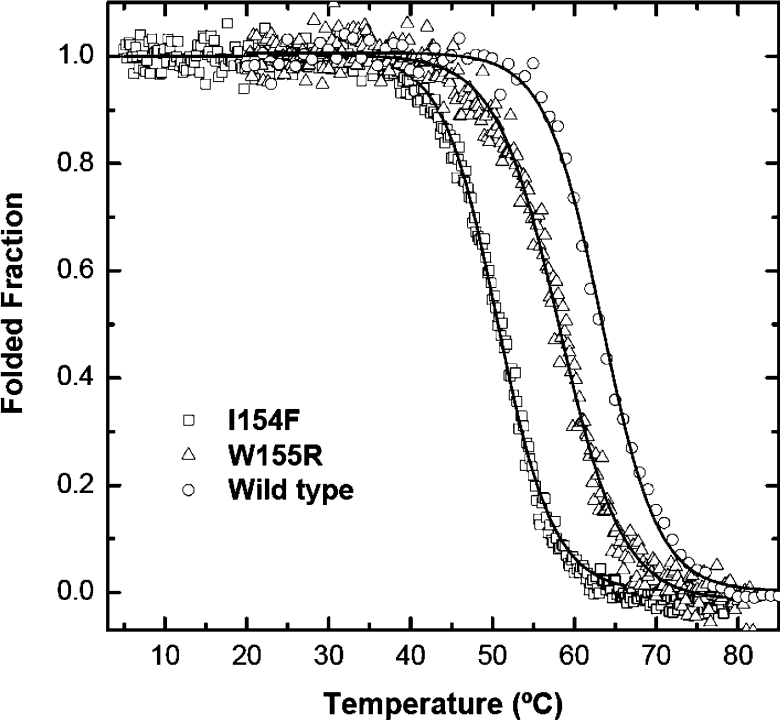

Frataxin mutants I154F and W155R have reduced thermodynamic stability

The conformational properties of the two Hfra-(91–210) mutants were investigated spectroscopically using fluorescence and far-UV CD. The differences in conformational stability between the wild-type Hfra-(91–210) and the two mutants were determined from the analysis of their chemical and thermal denaturation transitions, at pH 7 (Figures 5 and 6). In both cases, co-operative unfolding transitions were observed and, under the experimental conditions used, the unfolding reactions were found to be reversible. Concerning chemical unfolding, the order of the midpoint unfolding urea concentrations was determined to be wild-type>W155R>I154F Hfra (Table 4). The slightly higher m values determined for the two mutants also shows that a larger fraction of buried residues is exposed upon unfolding. The midpoint denaturation concentrations of the mutants were about one unit below that observed for the wild-type and this corresponded to a destabilization of 5.9–7.1 kJ (1.4–1.7 kcal) as a result of the mutations. Thermal unfolding experiments also revealed that the mutant I154F is more destabilized than the W155R having a Tm approx. 16 °C lower than the wild-type protein, whereas the mutant W155R shows a decrease of only approx. 5 °C. Taken together, these data reveal that both mutations under study reduce the thermodynamic stability of frataxin and that the mutation I154F is more aggressive.

Figure 5. Comparison of chemical denaturation of FRDA Hfra-(91–210) mutants at pH 7.0.

The wild-type Hfra-(91–210) (○) denaturation curve with urea is compared with that of Hfra-(91–210) W155R (△) and Hfra-(91–210) I154F (□). See Table 4 for parameters characterizing the urea denaturation.

Figure 6. Comparison of thermal denaturation of FRDA Hfra-(91–210) mutants at pH 7.0.

The wild-type Hfra-(91–210) (○) denaturation curve with urea is compared with that of Hfra-(91–210) W155R (△) and Hfra-(91–210) I154F (□).

Table 4. Parameters for urea denaturation of wild-type and mutant forms (I154F and W155R) to compare the differences in stability.

Δ[Urea]1/2=difference between the [urea]1/2 for the wild-type and the mutant forms. ΔΔG=from Δ[urea]1/2×average of the three m values [18].

| Protein | ΔGH2O (kJ·mol−1) | m (J·mol−1·M−1) | [Urea]1/2 (M) | Δ[Urea]1/2 | ΔΔG (J·mol−1) | Tm (°C) | ΔTm (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 24.3±1.3 | 5665±264 | 4.3 | 66.3±0.1 | |||

| W155R | 21.4±0.8 | 6209±327 | 3.4 | −0.9 | −7172 | 61.4±0.4 | −4.9 |

| I154F | 24.7±0.8 | 7687±281 | 3.2 | −1.1 | −5866 | 50.7±0.1 | −15.6 |

DISCUSSION

In the present paper, we have reported a detailed comparison of the thermodynamic properties of wild-type frataxin and two clinically relevant mutations (I154F and W155R) in FRDA. We have shown that, under chemically or thermally destabilizing conditions, the two mutants show distinct behaviours, but that they both are folded at physiological temperature and pH.

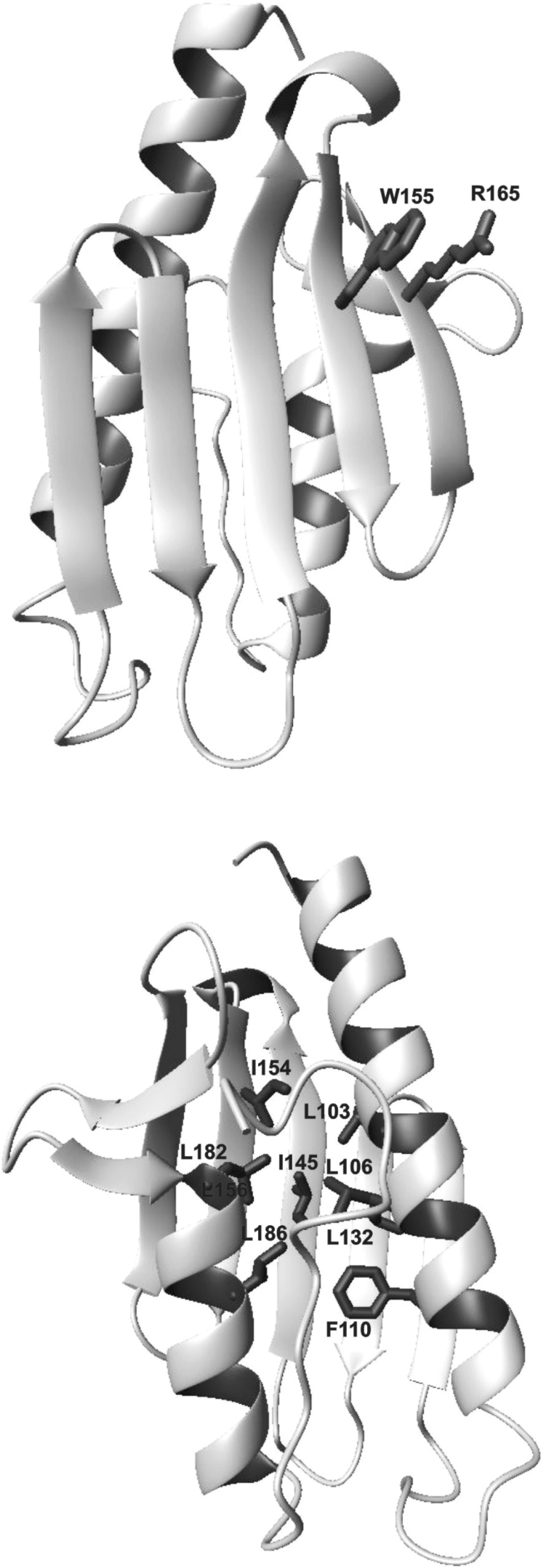

The mutation W155R, which can be included in the category of functional mutations, shows only some destabilization as compared with the wild-type. Destabilization is expected from the destruction of a π interaction between a tryptophan residue and the contiguous arginine residue (Arg165) (Figure 7), an interaction often observed in protein structures [26]. Additionally, introduction of another positively charged residue near Arg165 introduces further destabilization owing to electrostatic repulsion. Observation of these properties is therefore consistent with the location of the tryptophan residue on the external surface of the β-sheet, with its aromatic moiety completely exposed to the solvent, which is highly suggestive of a role in recognition or interaction with a partner.

Figure 7. Ribbon representation of the Hfra structure.

Two views differing by a 180° rotation around the y-axis are displayed. The side chains of Ile145 and Trp155 are shown (upper panel). The hydrophobic side chains of the residues which surround Ile145 and of Arg165 which packs against Trp155 are also marked (lower panel).

A significant perturbation was detected instead for the I154F mutant whose fold is substantially destabilized, as determined from the high number of peptides resulting from partial tryptic digestions and from a red shift in its fluorescence emission maximum. While this is reasonable, since the mutation affects a buried residues which takes part of the hydrophobic core (Figure 7) [13], the interesting observation is that the destabilization effect becomes evident only under stressing conditions. At room temperature, this mutant shows features very similar to those of the wild-type, suggesting that, despite the mutation, the protein can be correctly folded. Accordingly, I154F, as does W155R, partly retains its iron-binding capability, which nevertheless depends strongly on the specific three-dimensional scaffold. Correct folding would be essential to keep in spatial proximity the acidic residues found to be involved in iron binding, which are distributed along the first helix and in the first β-strand [24,25].

These observations are interesting because the severe effects of both mutations in FRDA patients would have possibly suggested a much stronger effect on the frataxin fold. What then is the mechanism that determines the pathology in heterozygous cases? The effect seems to be more subtle and could occur at two different levels. On the one hand, because of a higher destabilization, the folding efficiency once the protein is detached from the ribosome or migrates through the mitochondrial membrane could be reduced so that a lower concentration of ‘functional’ protein is released to the cell. On the other hand, the increased rate of proteolytic degradation also points out to a more efficient degradation of the mutant proteins. At the present stage, however, we do not have evidence of what the cellular fate of the mutant variant proteins upon their synthesis may be, but much more effort should be made to follow up these ideas. In vitro studies on mutant variants can therefore provide new experimental insights towards our understanding of the structural basis of the disease. The frataxin variants, which result in milder forms of the disease, are particularly interesting and are currently under investigation in our laboratories.

Acknowledgments

This work was partly supported by a collaborative grant from the Conselho Reitores das Universidades Portuguesas (CRUP), Portugal, to C.M.G. and the British Council (BC), U.K., to A.P. A.P. acknowledges funding from the FRDA and MDA foundations. Stephen Martin (National Institute for Medical Research) is thanked for valuable assistance and comments during CD measurements. Paula Chicau (Amino Acid Analysis Service, Instituto Tecnologia Química e Biológica) is gratefully acknowledged for skilled technical assistance on the HPLC separations of the limited proteolysis experiments.

References

- 1.Pandolfo M. Molecular pathogenesis of Friedreich ataxia. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:1201–1208. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.10.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamberlain S., Shaw J., Rowland A., Wallis J., South S., Nakamura Y., von Gabain A., Farrall M., Williamson R. Mapping of mutation causing Friedreich's ataxia to human chromosome 9. Nature (London) 1988;334:248–250. doi: 10.1038/334248a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramazzotti A., Vanmansart V., Foury F. Mitochondrial functional interactions between frataxin and Isu1p, the iron–sulfur cluster scaffold protein, in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2004;557:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01498-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duby G., Foury F., Ramazzotti A., Herrmann J., Lutz T. A non-essential function for yeast frataxin in iron–sulfur cluster assembly. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:2635–2643. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.21.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerber J., Muhlenhoff U., Lill R. An interaction between frataxin and Isu1/Nfs1 that is crucial for Fe/S cluster synthesis on Isu1. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:906–911. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon T., Cowan J. A. Frataxin-mediated iron delivery to ferrochelatase in the final step of heme biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:25943–25946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon T., Cowan J. A. Iron–sulfur cluster biosynthesis: characterization of frataxin as an iron donor for assembly of [2Fe–2S] clusters in ISU-type proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6078–6084. doi: 10.1021/ja027967i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bulteau A. L., O'Neill H. A., Kennedy M. C., Ikeda-Saito M., Isaya G., Szweda L. I. Frataxin acts as an iron chaperone protein to modulate mitochondrial aconitase activity. Science. 2004;305:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.1098991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park S., Gakh O., O'Neill H. A., Mangravita A., Nichol H., Ferreira G. C., Isaya G. Yeast frataxin sequentially chaperones and stores iron by coupling protein assembly with iron oxidation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:31340–31351. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cossee M., Durr A., Schmitt M., Dahl N., Trouillas P., Allinson P., Kostrzewa M., Nivelon-Chevallier A., Gustavson K. H., Kohlschutter A., et al. Friedreich's ataxia: point mutations and clinical presentation of compound heterozygotes. Ann. Neurol. 1999;45:200–206. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199902)45:2<200::aid-ana10>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campuzano V., Montermini L., Molto M. D., Pianese L., Cossee M., Cavalcanti F., Monros E., Rodius F., Duclos F., Monticelli A., et al. Friedreich's ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science. 1996;271:1423–1427. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5254.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adinolfi S., Trifuoggi M., Politou A. S., Martin S., Pastore A. A structural approach to understanding the iron-binding properties of phylogenetically different frataxins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:1865–1877. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.16.1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musco G., Stier G., Kolmerer B., Adinolfi S., Martin S., Frenkiel T., Gibson T., Pastore A. Towards a structural understanding of Friedreich's ataxia: the solution structure of frataxin. Structure. 2000;8:695–707. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00158-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhe-Paganon S., Shigeta R., Chi Y. I., Ristow M., Shoelson S. E. Crystal structure of human frataxin. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:30753–30756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Musco G., de Tommasi T., Stier G., Kolmerer B., Bottomley M., Adinolfi S., Muskett F. W., Gibson T. J., Frenkiel T. A., Pastore A. Assignment of the 1H, 15N, and 13C resonances of the C-terminal domain of frataxin, the protein responsible for Friedreich ataxia. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;15:87–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1008398832619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adinolfi S., Nair M., Politou A., Bayer E., Martin S., Temussi P., Pastore A. The factors governing the thermal stability of frataxin orthologues: how to increase a protein's stability. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6511–6518. doi: 10.1021/bi036049+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirley B. A. Urea and guanidine hydrochloride denaturation curves. Methods Mol. Biol. 1995;40:183–189. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-301-5:177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pace C. N., Shirley B. A., Thomson J. Measuring the conformational stability of proteins. In: Creighton T. E., editor. Protein Structure: a Practical Approach. Oxford: IRL Press; 1990. pp. 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pace C. N., Hebert E. J., Shaw K. L., Schell D., Both V., Krajcikova D., Sevcik J., Wilson K. S., Dauter Z., Hartley R. W., Grimsley G. R. Conformational stability and thermodynamics of folding of ribonucleases Sa, Sa2 and Sa3. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;279:271–286. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolis D., Politou A. S., Kelly G., Pastore A., Temussi P. A. Protein stability in nanocages: a novel approach for influencing protein stability by molecular confinement. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;336:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eftink M. R., Ghiron C. A. Fluorescence quenching studies with proteins. Anal. Biochem. 1981;114:199–227. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(81)90474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creighton T. E. Proteins: Structure and Molecular Properties. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company; 1996. Proteins in solution and in membranes: aqueous solubility; pp. 262–264. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fontana A., de Laureto P. P., Spolaore B., Frare E., Picotti P., Zambonin M. Probing protein structure by limited proteolysis. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2004;51:299–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nair M., Adinolfi S., Pastore C., Kelly G., Temussi P., Pastore A. Solution structure of the bacterial frataxin ortholog, CyaY: mapping the iron binding sites. Structure. 2004;12:2037–2048. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He Y., Alam S. L., Proteasa S. V., Zhang Y., Lesuisse E., Dancis A., Stemmler T. L. Yeast frataxin solution structure, iron binding, and ferrochelatase interaction. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16254–16262. doi: 10.1021/bi0488193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levitt M., Perutz M. F. Aromatic rings act as hydrogen bond acceptors. J. Mol. Biol. 1988;201:751–754. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]