Abstract

Hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) comprises a group of clinically and genetically heterogeneous diseases that affect the upper motor neurons and their axonal projections. For the novel SPG31 locus on chromosome 2p12, we identified six different mutations in the receptor expression–enhancing protein 1 gene (REEP1). REEP1 mutations occurred in 6.5% of the patients with HSP in our sample, making it the third-most common HSP gene. We show that REEP1 is widely expressed and localizes to mitochondria, which underlines the importance of mitochondrial function in neurodegenerative disease.

In hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP), the degeneration of corticospinal tract axons leads to progressive lower-limb spastic paralysis. Traditionally, HSP types have been divided into pure and complicated forms, which are characterized by additional symptoms such as mental retardation, epilepsy, cerebellar ataxia, or optic atrophy.1 Genetic studies have revealed as many as 31 different chromosomal HSP loci. Five genes have been identified for autosomal dominant subtypes.2 Mutations in the genes spastin (SPG4) and atlastin (SPG3A) account for up to 50% of all HSP cases. Mutations in KIF5A (MIM 602821), HSP60 (MIM 118190), and NIPA1 (MIM 608145) each occur in <1% of HSP cases.3,4

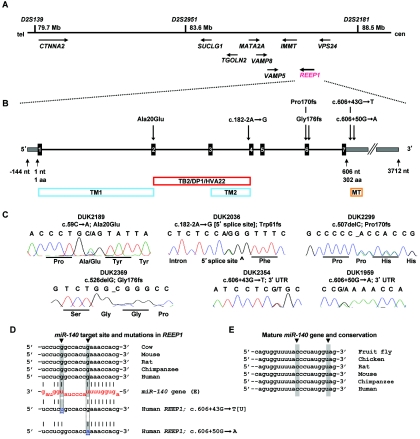

Elsewhere, we performed a genomewide linkage study and identified a “pure” HSP locus at chromosome 2p12 (SPG31).5 Two families, DUK2036 and DUK2299, yielded a combined two-point LOD score of 4.7 at marker D2S2951. Fine-mapping and haplotype analysis narrowed the locus to ∼8.8 Mb between D2S139 and D2S2181 (fig. 1A). We chose nine candidate genes (CTNNA2, SUCLG1, TGOLN2, MATA2A, VAMP8, VAMP5, IMMT, VPS24, and REEP1 [MIM 609139]) on the basis of emerging pathways for spastic paraplegia and conserved protein domains contained in proteins that cause neurodegenerative diseases.6 Of those genes, we sequenced all exons, including 40 bp of flanking intronic and UTR sequences. We identified a single base-pair deletion, c.507delC, in family DUK2299 and a splice-site mutation, c.182-2A→G, in family DUK2036 in the receptor expression–enhancing protein 1 gene (REEP1), also known as “C2orf23” (fig. 1B and 1C). These sequence changes resulted in frameshifts leading to altered stop codons. The mutations cosegregated with the disorder in the linked pedigrees (fig. 2). REEP1 (GenBank accession number NP_075063) belongs to a novel protein family that was identified only recently.7 Its subcellular location and molecular function are largely unknown. We screened for additional REEP1 mutations in a sample of 90 independent HSP-affected families of European descent, neither selected for pure HSP phenotype nor tested for mutations in other HSP genes. All individuals were studied under internal review board–approved procedures. We identified four more mutations that led to significant sequence changes in REEP1: one missense mutation (c.59C→A; Ala20Glu), one deletion (c.526delG; Gly176fs), and two 3′ UTR changes (c.606+43G→T and c.606+50G→A) (fig. 1B and 1C and table 1). All mutations cosegregated with the HSP phenotype in the available pedigrees and were undetected in 365 control individuals of European descent (730 chromosomes) (fig. 2).

Figure 1. .

Overview of the SPG31 locus and identified genetic variation in REEP1. A, Within the minimal chromosomal SPG31 region, we screened several genes by direct sequencing analysis. B, REEP1 consists of seven exons (black boxes) and contains two predicted transmembrane domains (TM1 and TM2) and a “deleted in polyposis” domain (TB2/DP1/HVA22). The 3′ UTR comprises a conserved miRNA target site for miR-140 (MT). C, Sequencing traces of the identified unique mutations in six families with uncomplicated HSP. Sequencing analysis was performed using an ABI3730, following standard procedures. PCR primers are available from the authors on request. D, The miR-140 target site in the 3′ UTR is highly conserved. Two mutations within that site change nucleotides that provide G:U wobble base pairing: c.606+43G→U and c.606+50G→A (gray shading, blue letters, and arrows). E, The mature miR-140 gene is also highly conserved, including the two residues that would bind to the mutated nucleotides in the target site (gray shading and arrows). cen = centromere; tel = telomere.

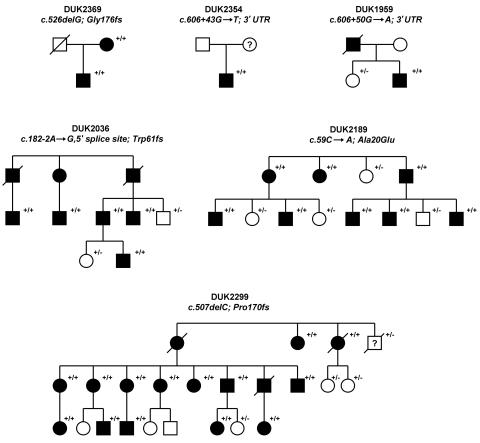

Figure 2. .

Different mutations identified in six unrelated HSP-affected families: DUK2369, DUK2354, DUK1959, DUK2036, DUK2189, and DUK2299. All families showed an uncomplicated HSP phenotype. The pedigrees present affected (blackened symbols) and unaffected (unblackened symbols) subjects. The clinical phenotypes were fully penetrant. All tested individuals are indicated (+/), as are mutations (/+) and wild-type genotypes (/−).

Table 1. .

Clinical and Genetic Features of the Identified Families with REEP1 Mutations

| Finding in Family |

||||||

| Characteristic | DUK2369 | DUK2354 | DUK1959 | DUK2036 | DUK2189 | DUK2299 |

| REEP1 mutation | c.526delG; Gly176fs | c.606+43G→T; 3′ UTR | c.606+50G→A; 3′ UTR | c.182-2A→G, 5′ splice site; Trp61fs | c.59C→A; Ala20Glu | c.507delC; Pro170fs |

| Age at onset (years) | 18 | 6 | 40 | 5–18 | 3–62 | 3–60 |

| Typical HSP neurologic features | Lower limb weakness, spastic gait, mild distal atrophy | Lower limb weakness, spastic gait | Lower limb weakness, spastic gait, ankle clonus | Lower limb weakness, spastic gait, ankle clonus | Lower limb weakness, spastic gait | Lower limb weakness, spastic gait, ankle clonus |

| Other features | Mild scoliosis | None | Mild distal sensory neuropathy | Mild scoliosis | Learning difficulties in two affected individuals | None |

| Babinski sign | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Imaginga | Normal cranial MRI | Normal cranial and spinal MRI | Normal spinal MRI | Normal spinal MRI | Normal spinal MRI | Normal spinal MRI |

MRI = magnetic resonance imaging.

The splice-site mutation in linked family DUK2036 disrupted the canonical 5′ acceptor splicing signal “AG” of exon 4 (fig. 1B and 1C). REEP1 was not expressed in peripheral-blood cells, and neuronal tissue was not available from affected family members (fig. 3K). Thus, we could not demonstrate the aberrant mRNA (GenBank accession number NM_022912), but simulation of the resulting splice efficiency with NNSPLICE revealed a reduction from 99% efficiency of the wild-type AG allele to 0% of the mutant GG allele. Missplicing of exon 4 will result in a frameshift followed by a premature stop codon. The two mutations in the 3′ UTR presented unusual changes for a Mendelian disease. However, both mutations altered the sequence of a predicted highly conserved binding site for the microRNA (miRNA) gene miR-140 (fig. 1D and 1E). miRNAs constitute a new large class of small noncoding RNA genes that target protein-coding genes for posttranscriptional repression8 (see the MicroRNA Registry). The c.606+43G→T mutation in REEP1 disrupted a G:U wobble base pair, and the c.606+50G→A change replaced a G:U wobble base pair with an A:U Watson-Crick pairing. It has been shown that G:U wobble base pairing has an inhibitory effect on miRNA-mediated repression of translation.9 Thus, both detected mutations would foster suppressive miRNA-mediated effects on translation, leading to less available REEP1 protein. Both affected nucleotides are highly conserved in the REEP1 3′ UTR as well as in miR-140 of different species (fig. 1D and 1E). In addition, it has been shown that miR-140 is expressed in the cortex of rat and monkey as well as in cultured primary cortical neurons from rat.10,11 Thus, we suggest that the identified sequence variants will affect the amount of translated REEP1 in patients with HSP.

Figure 3. .

REEP1 localized to mitochondria. A–F, Immunohistochemistry with two different REEP1 antibodies revealed colocalization with the marker Mitotracker Red. COS7 (kidney) and MN-1 (motor neuron) cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and were incubated at 37°C supplemented with 5% CO2. Cells were observed by confocal laser scan microscopy (Visitech model VT-Infinity). G and H, No colocalization was observed with microtubules and Golgi. I, COS7 cells were homogenized and mitochondria were separated from the cytosolic fraction by centrifugation. The REEP1 antibodies were probed against COS7 cell lysate on a western blot and showed a band of the expected size in the mitochondrial fraction. The blot was reprobed with porin, which constitutes a mitochondrial membrane protein, and β-actin. Note that the cytosolic fraction was highly enriched, as shown by the β-actin bands. J, RT-PCR on a series of tissues revealed ubiquitous expression. REEP1 was not expressed in peripheral blood and fibroblasts derived from a skin biopsy.

Three of the four coding changes led to alternative stop codons. It is likely that the resulting mRNA will be targeted for nonsense-mediated decay, resulting in haploinsufficiency of the mutant allele. Interestingly, both miRNA target-site mutations disrupted G:U base pairing and are therefore likely to lead to less translated protein. We suggest that loss of function and haploinsufficiency are the mechanisms of action in REEP1-related spastic paraplegia.

As shown by Saito et al.7 and extended in the present study, REEP1 is expressed in various nonneuronal and neuronal tissues, including spinal cord (fig. 3K). This follows the now-common finding of almost ubiquitous tissue expression for a number of genes that cause distinct neurodegenerative phenotypes. Saito et al. showed that REEP1 has a weak promoting effect on the expression of G protein–coupled odorant-receptor proteins at the cell surface.7 Thus, REEP1 might have a role in trafficking of odorant receptors and other molecules through cellular compartments such as the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. The yeast homologue of REEP1, Yop1P, is involved in Rab-mediated vesicle transport, a pathway that has recently been implicated in axonal neuropathy type CMT2B, which is caused by mutations in RAB7.12,13 In silico analysis of REEP1 predicted two transmembrane domains and the conserved protein domain TB2/DP1/HVA22 (fig. 1B). As shown by Chen et al., the plant homologues of HVA22 are stress-induced genes—a characteristic known from heat-shock proteins.14 Heat-shock proteins play a fundamental role as chaperones to promote and maintain correct protein folding, especially in cell compartments rich in reactive oxygen species, such as mitochondria. Mutations in the mitochondrial heat-shock protein 60 have been shown to cause spastic paraplegia type SPG13.4 It has also been suggested that the spastic paraplegia gene paraplegin (SPG7 [MIM 602781]) fulfills chaperonelike activities in mitochondria.15

We designed two specific polyclonal antibodies that targeted the C terminal of REEP1 (fig. 4). Staining of COS7 and MN-1 cells with those antibodies revealed that endogenous REEP1 colocalized with mitochondria (fig. 3A–3F). REEP1 was also present in the mitochondrial but not the cytosolic cellular fraction on an immunoblot (fig. 3I). Given the predicted transmembrane domains (figs. 1B and 5), we suggest that REEP1 is a novel mitochondrial membrane protein.

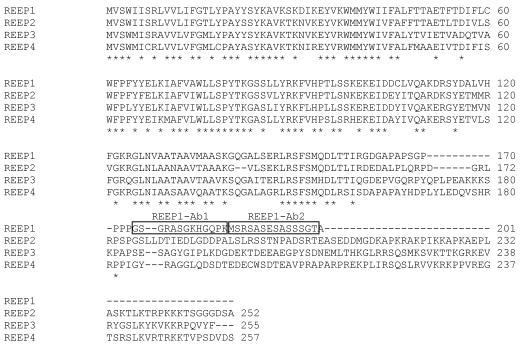

Figure 4. .

Antibody design for REEP1. The proteins REEP1 through REEP4 are fairly conserved in human; thus, we chose two peptides in the less-conserved C terminal of REEP1 to be targeted by two polyclonal antibodies (frames). Two rabbits were injected with the synthetic peptides. Blood was collected after 50 d and was purified through keyhole-limpet-hemocyanin columns. All peptide synthesis work and antibody production was performed at Bethyl Laboratories.

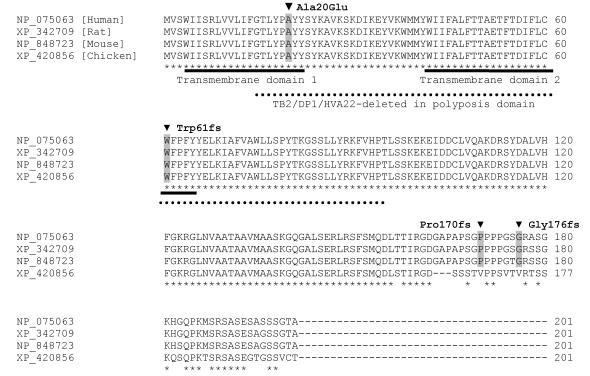

Figure 5. .

REEP1 is highly conserved throughout different species. Detected mutations in patients with HSP are highlighted in gray. Both transmembrane domains and the TB2/DP1/HVA22 domain are affected by two of the identified mutations. Stars highlight conserved residues.

Although the results of Saito et al. suggested localization of REEP1 to the secretory pathway,7 we did not detect colocalization of REEP1 with the Golgi (fig. 1H). It is conceivable that REEP1 has different cellular functions and that a fraction of the protein, which was not detectable with the available antibodies, indeed fulfills functions in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. In support of this hypothesis, the ENSEMBL human genome database lists two alternative isoforms of REEP1 that might represent such differential functionality. However, we were not able to unequivocally reproduce the existence of this second isoform.

Although the specific function of REEP1 in mitochondria has not been elucidated, this finding contributes further to the evidence that mitochondrial integrity takes center stage in HSP and related neurodegenerative diseases.6

In summary, we have identified the gene for the SPG31 locus, REEP1, which accounted, in our sample, for 6.5% of all HSP cases. We have demonstrated that REEP1 is localized to mitochondria, and, derived from its conserved protein-domain structure, REEP1 might be involved in chaperonelike activities.

Acknowledgments

The cooperation of patients and families involved in this study is gratefully acknowledged. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (to M.A.P.-V.) and by donations from family members and friends of families with HSP to the Center for Human Genetics.

Web Resources

Accession numbers and URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/ (for the REEP1 protein [accession number NP_075063] and REEP1 mRNA [accession number NM_022912])

- MicroRNA Registry, http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/

- Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim/ (for KIF5A, HSP60, NIPA1, REEP1, and SPG7)

References

- 1.Reid E (1999) The hereditary spastic paraplegias. J Neurol 246:995–1003 10.1007/s004150050503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fink JK (2003) Advances in the hereditary spastic paraplegias. Exp Neurol Suppl 184:S106–S110 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reid E, Kloos M, Ashley-Koch A, Hughes L, Bevan S, Svenson IK, Graham FL, Gaskell PC, Dearlove A, Pericak-Vance MA, Rubinsztein DC, Marchuk DA (2002) A kinesin heavy chain (KIF5A) mutation in hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG10). Am J Hum Genet 71:1189–1194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen JJ, Durr A, Cournu-Rebeix I, Georgopoulos C, Ang D, Nielsen MN, Davoine CS, Brice A, Fontaine B, Gregersen N, Bross P (2002) Hereditary spastic paraplegia SPG13 is associated with a mutation in the gene encoding the mitochondrial chaperonin Hsp60. Am J Hum Genet 70:1328–1332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Züchner S, Kail M, Nance M, Gaskell PC, Svenson IK, Marchuk DA, Pericak-Vance MA, Allison-Koch AE (2006) A new locus for dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia maps to chromosome 2p12. Neurogenetics 7:127–129 10.1007/s10048-006-0029-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Züchner S, Vance JM (2005) Emerging pathways for hereditary axonopathies. J Mol Med 83:935–943 10.1007/s00109-005-0694-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saito H, Kubota M, Roberts RW, Chi Q, Matsunami H (2004) RTP family members induce functional expression of mammalian odorant receptors. Cell 119:679–691 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartel DP (2004) MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116:281–297 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doench JG, Sharp PA (2004) Specificity of microRNA target selection in translational repression. Genes Dev 18:504–511 10.1101/gad.1184404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Townsend M, Yoshii A, Sestan N, Rakic P, Constantine-Paton M, Horvitz HR (2004) Microarray analysis of microRNA expression in the developing mammalian brain. Genome Biol 5:R68 10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-r68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim J, Krichevsky A, Grad Y, Hayes GD, Kosik KS, Church GM, Ruvkun G (2004) Identification of many microRNAs that copurify with polyribosomes in mammalian neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:360–365 10.1073/pnas.2333854100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verhoeven K, De Jonghe D, Coen K, Verpoorten N, Auer-Grumbach M, Kwon JM, FitzPatrick D, Schmedding E, De Vriendt E, Jacobs A, Van Gerwen V, Wagner K, Hartung H-P, Timmerman V (2003) Mutations in the small GTP-ase late endosomal protein RAB7 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2B neuropathy. Am J Hum Genet 72:722–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxena S, Bucci C, Weis J, Kruttgen A (2005) The small GTPase Rab7 controls the endosomal trafficking and neuritogenic signaling of the nerve growth factor receptor TrkA. J Neurosci 25:10930–10940 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2029-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen CN, Chu CC, Zentella R, Pan SM, Ho TH (2002) AtHVA22 gene family in Arabidopsis: phylogenetic relationship, ABA and stress regulation, and tissue-specific expression. Plant Mol Biol 49:633–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casari G, De Fusco M, Ciarmatori S, Zeviani M, Mora M, Fernandez P, De Michele G, Filla A, Cocozza S, Marconi R, Durr A, Fontaine B, Ballabio A (1998) Spastic paraplegia and OXPHOS impairment caused by mutations in paraplegin, a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial metalloprotease. Cell 93:973–983 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81203-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]