Abstract

Background

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) causes severe infections in very young infants and invasive disease in pregnant women and adults with underlying medical conditions. GBS pathogenicity varies between and within serotypes, with considerable variation in genetic content between strains. Three proteins, Rib encoded by rib, and alpha and beta C proteins encoded by bca and bac, respectively, have been suggested as potential vaccine candidates for GBS. It is not known, however, whether these genes occur more frequently in invasive versus colonizing GBS strains.

Methods

We screened 162 invasive and 338 colonizing GBS strains from different collections using dot blot hybridization to assess the frequency of bca, bac and rib. All strains were defined by serotyping for capsular type, and frequency differences were tested using the Chi square test.

Results

Genes encoding the beta C protein (bac) and Rib (rib) occurred at similar frequencies among invasive and colonizing isolates, bac (20% vs. 23%), and rib (28% vs. 20%), while the alpha (bca) C protein was more frequently found in colonizing strains (46%) vs, invasive (29%). Invasive strains were associated with specific serotype/gene combinations.

Conclusion

Novel virulence factors must be identified to better understand GBS disease.

Background

Group B Streptococcus (GBS) causes sepsis and meningitis in young infants, febrile complications in pregnant women and invasive disease in adults with underlying medical conditions [1]. Capsular polysaccharide, which defines GBS serotype, is the primary virulence factor found in most GBS strains, and different serotypes contribute to disease in different populations. For example, 30% of GBS disease in non-pregnant adults is caused by serotype V [2], while serotype III causes more than 70% of infant meningitis and most late-onset (7–89 days of age) disease [3]. Vaccines currently under development target the most prevalent GBS serotypes [4].

Other than the polysaccharide capsule, little is known about other GBS components important in pathogenesis. Many putative virulence factors and genes have been identified recently (for a review see [5]), though most are either present in all GBS strains, or are lacking sufficient data to pinpoint their role in the pathogenic process. Three proteins, however, have been studied extensively and were recommended as potential GBS vaccine candidates [6-8]. These include the protein Rib [7] encoded by rib [9], and the alpha [10] and beta [10] C proteins encoded by bca [11] and bac [12], respectively. All three proteins trigger antibody production that offers protection from GBS infection in animal models [7,8,13], though the frequency of these proteins and the genes that encode them varies by disease status [14-19] as well as serotype. For example, Rib has been found predominantly in serotype III strains [7]. To date, large, population-based studies comparing the frequencies of genes encoding the Rib, alpha and beta C proteins among invasive and colonizing isolates have been limited.

Methods

We describe the frequency of genes encoding three virulence factors among five GBS strain collections including invasive (n = 162) and colonizing (n = 338) isolates (Table 1); invasive disease status was not known for 29 strains. All isolates tested were obtained with the approval of an appropriate institutional ethics committee. Invasive isolates originated from the blood or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of newborns <7 days of age (n = 100), the urine of college students (n = 4) [20,21] and pregnant women presenting to the University of Michigan Medical Center (UMMC) for prenatal care associated with GBS isolation from the urine (n = 58), and the placenta following delivery (n = 5) [22]. Newborn isolates, described by Zaleznik et al. [23] (n = 65), were collected between 1993 and 1996, while the remainder (n = 35) came from the same Houston hospitals between 1997 and 2000. Colonizing GBS isolates were from the anal orifice or urine of healthy male (n = 58) college students, the anal orifice, vagina, cervix or urine or healthy female (n = 86) college students [21], pregnant women from UMMC (n = 49) [22], and sexually active college women with a urinary tract infection not caused by GBS (n = 102) and their most recent male sex partner (n = 43) [20]. Among colonizing isolates, 17 (6.9%) were from individuals colonized with multiple isolates in multiple sites; the dot blot profile was determined only for those isolates that were unique by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) as described previously [20,21,24].

Table 1.

Number of group B streptococcal isolates (n = 529) screened via dot blot hybridization and characteristics of each collection*.

| GBS Collection | Isolation source | Culture date | Age range | Race/ethnicity | Number of strains |

| 1a. Sexually active college women with UTI receiving care from a Student Health Services at the University of Michigan (UM) [22]. | urine, anal orifice, vaginal | Sept. 1996 to April 1999 | 18–30 | White (76%), Non-White (24%) | Colonizing (n = 102), Invasive† (n = 2) |

| 1b. Most recent male sex partner of women with UTI receiving care from the Student Health Services at UM [22]. | urine, anal orifice | Sept. 1996 to April 1999 | 18–35 | White (71%), Non-White (29%) | Colonizing (n = 43), Invasive† (n = 0) |

| 2a. Sexually active college women without UTI presenting to the Student Health Services at UM [22]. | urine, anal orifice, vaginal | Sept. 1996 to April 1999 | 18–28 | White (80%), Non-White (20%) | Colonizing (n = 57), Invasive† (n = 0) |

| 2b. Most recent male sex partner of women without UTI presenting to the Student Health Services at UM [22]. | urine, anal orifice | Sept. 1996 to April 1999 | 19–33 | White (73%), Non-White (27%) | Colonizing (n = 35), Invasive† (n = 0) |

| 3. Newborns with early onset disease from hospitals affiliated with Baylor College of Medicine [19]. | blood, CSF | 1993 to 2000 | < 7 days | Hispanic (56%), African American (24%), Caucasian (16%), Asian (4%) | Colonizing (n = 0), Invasive† (n = 100) |

| 4a. Random sample of college aged women from the UM community [21] | urine, anal orifice, vaginal | Sept. to Nov. 1998 | 17–49 | Caucasian (65%), Asian (16%), African American (10%), Hispanic (5%), Other (5%) | Colonizing (n = 29), Invasive† (n = 1) |

| 4b. Random sample of college aged men from the UM community [21] | urine, anal orifice | Sept. to Nov. 1998 | 19–45 | Caucasian (60%), Asian (28%), African American (4%), Hispanic (3%), Other (4%) | Colonizing (n = 23), Invasive† (n = 1) |

| 5. Pregnant women presenting at the UM Medical Center for prenatal care [34]. | urine, rectal, vaginal, placental | Aug. 1999 to Mar. 2000 | 16–42 | Caucasian (67%), African American (18%), Other (7%), Unknown (9%) | Colonizing (n = 49), Invasive† (n = 53), Unknown (n = 29) |

* Seventeen individuals (7 from collection 1a, 4 from collection 2a, 3 from collection 2b, and 3 from collection 4b) were colonized with two genetically distinct strains, as determined by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

†Invasive isolates originated from the blood or cerebrospinal fluid of newborns <7 days of age, the urine of adults at ≥100,000 cfu/ml, pregnant women presenting for prenatal care associated with GBS isolation from the urine, and the placenta following delivery. Colonizing GBS were from the anal orifice, lower vagina, cervix or urine of healthy individuals, and sexually active college women with a urinary tract infection not caused by GBS.

Serotyping using hyperimmune rabbit antisera to GBS polysaccharide types Ia, Ib, and II-VIII was performed as described previously [20,21]. We amplified DNA for genes encoding bca, bac and rib using PCR (Table 2). Control strain A909 was used to amplify bca and bac [25], while BM110 was used for rib [9]. PCR DNA was purified and fluorescein-labeled as described previously [26].

Table 2.

PCR primers used to amplify DNA regions specific to the genes encoding the alpha (bca) and beta (bac) C proteins, and the protein Rib (rib).*

| Gene | Forward primer Reverse primer | Reference | Size | Annealing temperature | Extension time |

| bca | 5'-TAACAGTTATGATACTTCACAGAC-3' | [11] | 535 bp | 68°C | 33 sec |

| 5-'ACGACTTTCTTCCGTCCACTTAGG-3' | |||||

| bac | 5'-CTATTTTTGATATTGACAATGCAA-3' | [12] | 592 bp | 60°C | 36 sec |

| 5'-GTCGTTACTTCCTTGAGATGTAAC-3' | |||||

| rib | 5'-CAGGAAGTGCTGTTACGTTAAAC-3' | [9] | 369 bp | 58°C | 22 sec |

| 5'-CGTCCCATTTAGGGTCTTCC-3' |

* PCR conditions for each reaction included a five minute denaturation step at 95°C, and 30 cycles of the following: 35 second denaturation, 40 second annealing and varying extension times. The extension temperature was 73°C for all reactions.

DNA was isolated using a modified E. coli protocol [27] in which cells were lysed overnight. Dot blot hybridization and subsequent analyses were performed as described previously [26,28] with two negative and positive controls per membrane. The signal intensity of each dot was reported as a percentage of the positive control present on each membrane in ImageQuant (Molecular Dynamics, CA). Percentages were corrected for the background signal of the negative controls and graphed. The x-axis represented values from one membrane and the y-axis consisted of values from the duplicate membrane. A cutoff was established based on each graph distribution [26]. Isolates within the intermediate range were repeated. Sixty-eight hybridizations yielded equivocal results despite repeated probing, and thus, were confirmed for the presence or absence of each gene by PCR and sequencing using the same primers described in Table 2. Eleven remained equivocal following PCR and were excluded from the analyses.

Chi square tests were used to assess differences in gene frequencies by collection and serotype. SAS was used for all statistical analyses [29].

Results

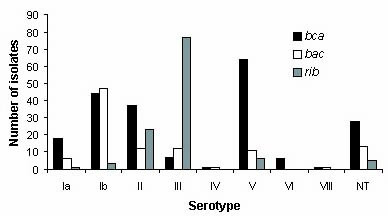

Across GBS strain collections, the bca gene occurred most frequently, followed by rib and bac (Table 3). bca and bac occurred most frequently among colonizing isolates from college students (Collections 1, 2, and 4, Table 1), while the frequency of rib was similar across collections. Because gene frequency varies by capsular serotype, we described the frequency of each gene by serotype (Figure 1). When assessing the frequencies among invasive versus colonizing isolates, only isolates from newborns with GBS disease (n = 100) were considered invasive, while colonizing isolates consisted of those isolates known to not cause a UTI and those that were isolated during pregnancy as part of routine GBS screening (n = 360). In this analysis, rib occurred slightly more frequently among invasive versus colonizing isolates (p = .09) (Table 4), while both bac (p = .55) and bca (p = .002) occurred less frequently in the invasive strains.

Table 3.

The frequency of genes encoding the alpha (bca) and beta (bac) C protein, and the protein Rib (rib) among various GBS populations.

| alpha antigen (bca) ‡ | beta antigen (bac) ‡ | Rib protein (rib) | |||||||

| GBS Collection | Number screened | n | (%) | Number screened | n | (%) | Number screened | n | (%) |

| 1. Sexually active college women with UTI and sex partner† | 145 | 63 | (43) | 147 | 26 | (18) | 146 | 33 | (23) |

| 2. Sexually active college women without UTI and their sex partner | 93 | 58 | (62) | 93 | 26 | (28) | 93 | 17 | (18) |

| 3. Infected newborns < 7 days of age | 100 | 29 | (29) | 100 | 20 | (20) | 100 | 28 | (28) |

| 4. Random sample of college students† | 53 | 25 | (47) | 53 | 18 | (34) | 53 | 13 | (25) |

| 5. Pregnant women | 135 | 41 | (30) | 131 | 18 | (14) | 134 | 27 | (20) |

| Total | 526 | 216 | (41) | 524 | 108 | (21) | 526 | 118 | (22) |

Note: n (%) represents the number of participants with the respective gene in each population; the number screened varies slightly by gene and population because a result could not be obtained for 4 strains tested for rib and bca, and 6 strains tested for bac despite repeated testing.

†There was no difference in gene frequency by gender so the results were combined for presentation.

‡Using the Chi-square test, a significant difference at the p = .05 significance level was observed between bca frequencies in collection 2 versus 3 (p < .0001), 5 (p < .0001) and 1 (p = .004); and between bac frequencies in collection 2 versus 5 (p = .008).

Figure 1.

The number of strains with genes encoding the alpha (bca) and beta (bac) C proteins and the protein Rib (rib) by serotypes Ia (n = 115), Ib (n = 60), II (n = 67), III (n = 84*), IV (n = 2), V (n = 105*), VI (n = 7*), VIII (n = 1), and nontypeable (NT) (n = 53). The sample represents the maximum number of isolates tested, which varied slightly by gene; serotyping data was not available for 35 strains.

Table 4.

Frequency of genes encoding the alpha (bca) and beta (bac) C proteins, and the protein Rib (rib) among invasive versus colonizing group B streptococcal isolates by serotype.

| Invasive n (%) | Colonizing n (%) | |||||

| bca | bac | rib | bca | bac | rib | |

| Overall freq. | 29/100 (29) | 20/100 (20) | 28/100 (28) | 167/360 (46)* | 82/360 (23) | 72/360 (20)† |

| By Serotype | ||||||

| Ia | 0/33 (0) | 0/43 (0) | 0/33 (0) | 18/71 (25)* | 6/71 (8)† | 1/71 (1) |

| Ib | 12/12 (100) | 11/12 (92) | 0/12 (0) | 29/42 (69)* | 32/42 (76) | 3/42 (7) |

| II | 8/15 (53) | 2/15 (13) | 5/15 (33) | 25/45 (56) | 10/45 (22) | 15/45 (33) |

| III | 0/23 (0) | 6/23 (26) | 23/23 (100) | 5/44 (11)† | 4/44 (9)† | 39/44 (89)† |

| IV | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 1/2 (50) | 1/2 (50) | 0/2 (0) |

| V | 8/15 (53) | 1/15 (7) | 0/15 (0) | 51/76 (67) | 10/78 (13) | 6/78 (8) |

| VI | 0/0 (0) | 0/1 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 5/6 (83) | 0/6 (0) | 0/0 (0) |

| VIII | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 1/1 (100) | 1/1 (100) | 0/0 (0) |

| NT | 0/0 (0) | 0/10 (0) | 0/0 (0) | 23/41 (56) | 13/41 (32) | 5/41 (12) |

Note: Serotype data are missing for 30 strains.

*The difference in the gene frequency between invasive and colonizing populations is statistically significant at p < .05 using the Chi square test.

†Marginally significant Chi square estimate (.06 < p < .10)

After stratifying by serotype, invasive versus colonizing capsular serotype Ia strains were significantly less likely to have bca (p = .002), while Ib invasive strains were more likely to have bca (p = .03) (Table 4). Invasive versus colonizing capsular serotype III strains, however, were more likely to have both rib (p = .09) and bac (p = .06), and less likely to have bca (p = .09).

Because a previous study also indicated that rib occurs more frequently in invasive isolates [7], we further examined its frequency by colonization site. Among invasive isolates from newborns, the odds of isolation from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) compared to blood was 3.6 higher when rib [95% CI: (0.86, 15.44), p = .04], and 4.1 times higher when bac [95% CI: (0.92, 17.91), p = .03] were present. There was no association with bca. Because rib occurred in 92% of capsular serotype III isolates and was found infrequently in other serotypes, and type III occurred more frequently among infants with invasive disease, it is likely that the association with CSF is attributable to confounding. When we examined the colonization site by serotype among rib positive strains, 26% of serotype III and no serotype II strains (the only other serotype with rib) were isolated from the CSF. By contrast, among isolates without rib, 6%, 10% and 17% of serotype Ia, II and Ib strains, respectively, were isolated from the CSF. In a similar analysis of among bac positive strains, 50% of serotype III and 18% of serotype Ib, but no serotype II or V strains were isolated from the CSF. When the analysis was restricted to serotype III strains, rib was not associated with CSF isolation, but bac was (OR: 4.7, 95% CI: 0.43, 60.74), although the sample size was too small to achieve statistical significance (p = .12).

The bca and bac genes frequently occurred together; 74 strains contained both genes among 324 strains with at least one gene (p < .0001). rib was significantly less likely to occur with either bca (11/333, p < .0001) or bac (14/224, p = .01). These relationships were similar when stratified by isolate type with a few exceptions. Among the 14 strains with rib and bac, 8 (57%) were invasive (p = .002); 7 of these 8 were from newborns and 6 of the 7 newborn strains were serotype III. Strains with both bca and rib together were more frequent in colonizing versus invasive strains (p = .03) as were strains with both bca and bac (p = .10).

Discussion

Based on the suggestion that the alpha and beta C proteins and protein Rib protein serve as potential vaccine GBS candidates either in glycoconjugates or alone [6-8], it was estimated in 1988, before the emergence of serotype V GBS, that a vaccine containing the alpha C protein and a serotype III component would prevent at least 90% of GBS cases [30]. Although we did not find these three genes significantly more frequently in invasive versus colonizing GBS strains, bac was found more frequently among isolates from CSF than blood in invasive serotype III isolates from newborns, suggesting it may increase disease severity.

Although we detected differences in the frequency of specific genes, it is possible that the encoded proteins are differentially expressed [31,32] and thus, differences in pathogenicity could be attributable to differences in gene expression. A prior study demonstrated that protein Rib [7] was present in more invasive versus colonizing serotype III strains. In this study, invasive strains were more likely to have rib (p = .09), but the association was only marginally significant. A similar observation was found for bac (p = .06), which is consistent with a prior report [18]. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the differences in collection date and geographic location are responsible for this result. Further, and possibly more important, the isolates assessed may contain other unknown virulence characteristics important to invasion, as the virulence of GBS is probably attributable to multiple genes. Our collections of invasive isolates were limited to those from newborns, pregnant women and healthy young women. It is possible that these virulence genes might have different impacts in other susceptible populations, such as the elderly or those with underlying chronic disease.

Conclusion

We observed only a marginally significant difference in bac, bca and rib frequency between invasive and colonizing serotype III strains, thereby raising the possibility that other genes explain the association of serotype III with invasive disease. It is noteworthy, however, that both rib and bac were found more frequently in the newborn serotype III isolates, while bca was found less frequently. Because various genotyping methods, such as multilocus sequence typing (MLST), have distinguished between colonizing and invasive strains, [33] this warrants further study. Using the framework provided by MLST, for example, may allow us to assess the distribution of these genes by sequence types found to be associated with invasiveness. In addition, it is clear that GBS disease pathogenesis is complex, thus novel virulence genes need to be identified and evaluated to understand their role in the pathogenic process, and provide additional vaccine targets. Recently published GBS DNA sequences [34-36] will facilitate the identification of these novel factors.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

SDM conducted the data analysis and drafted the manuscript, MK performed the PCR on strains yielding an equivocal result; CFM and BF oversaw and participated in the study design, analysis and writing; KJK and SMB performed the dot blot assays; and CJB provided strains, performed serotyping and assisted with the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Patricia Tallman for maintaining the GBS collections; Melissa E. Ward for serotyping the GBS isolates; Lixin Zhang for technical advice; Gunnar Lindahl for providing strain BM110; and Yuan Gu for performing dot blot hybridization. This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI44868 (BF) and AI51675 (BF) from the National Institute of Health (NIH), and in part by NIH Public Health Service grant AI066081(SDM). Collection, maintenance of isolates and serotyping by CJB was supported in part by NIH-NIAID contract N01 AI75326. Serotyping was paid in part by grant 334-SAP/99 (SDM) from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, and the University of Michigan Medical School's Advisory Council on Clinical Research (Mark D. Pearlman, M.D.)

Contributor Information

Shannon D Manning, Email: Shannon.Manning@ht.msu.edu.

Moran Ki, Email: kimoran@eulji.ac.kr.

Carl F Marrs, Email: cfmarrs@umich.edu.

Kiersten J Kugeler, Email: bio1@cdc.gov.

Stephanie M Borchardt, Email: Stephanie.Borchardt@va.gov.

Carol J Baker, Email: cbaker@bcm.tmc.edu.

Betsy Foxman, Email: bfoxman@umich.edu.

References

- Schrag SJ, Zell ER, Lynfield R, Roome A, Arnold KE, Craig AS, Harrison LH, Reingold A, Stefonek K, Smith G, Gamble M, Schuchat A. A population-based comparison of strategies to prevent early-onset group B streptococcal disease in neonates. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:233–239. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison LH, Elliott JA, Dwyer DM, Libonati JP, Ferrieri P, Billmann L, Schuchat A. Serotype distribution of invasive group B streptococcal isolates in Maryland: implications for vaccine formulation. Maryland Emerging Infections Program. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:998–1002. doi: 10.1086/515260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies HD, Raj S, Adair C, Robinson J, McGeer A. Population-based active surveillance for neonatal group B streptococcal infections in Alberta, Canada: implications for vaccine formulation. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:879–884. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200109000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CJ, Edwards MS. Group B streptococcal conjugate vaccines. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:375–378. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.5.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning SD. Molecular epidemiology of Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus) Front Biosci. 2003;8:s1–18. doi: 10.2741/985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker CJ. Immunization to prevent group B streptococcal disease: victories and vexations. J Infect Dis. 1990;161:917–921. doi: 10.1093/infdis/161.5.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalhammar-Carlemalm M, Stenberg L, Lindahl G. Protein rib: a novel group B streptococcal cell surface protein that confers protective immunity and is expressed by most strains causing invasive infections. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1593–1603. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gravekamp C, Kasper DL, Paoletti LC, Madoff LC. Alpha C protein as a carrier for type III capsular polysaccharide and as a protective protein in group B streptococcal vaccines. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2491–2496. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2491-2496.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wastfelt M, Stalhammar-Carlemalm M, Delisse AM, Cabezon T, Lindahl G. Identification of a family of streptococcal surface proteins with extremely repetitive structure. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18892–18897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevanger L, Maeland JA. Complete and incomplete Ibc protein fraction in group B streptococci. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [B] 1979;87B:51–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1979.tb02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel JL, Madoff LC, Olson K, Kling DE, Kasper DL, Ausubel FM. Large, identical, tandem repeating units in the C protein alpha antigen gene, bca, of group B streptococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:10060–10064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.21.10060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerlstrom PG, Chhatwal GS, Timmis KN. The IgA-binding beta antigen of the c protein complex of Group B streptococci: sequence determination of its gene and detection of two binding regions. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:843–849. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachenauer CS, Baker CJ, Baron MJ, Kasper DL, Gravekamp C, Madoff LC. Quantitative determination of immunoglobulin G specific for group B streptococcal beta C protein in human maternal serum. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:368–374. doi: 10.1086/338773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, Ferrieri P. Group B streptococcal Ibc protein antigen: distribution of two determinants in wild-type strains of common serotypes. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;19:506–510. doi: 10.1128/jcm.19.4.506-510.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madoff LC, Hori S, Michel JL, Baker CJ, Kasper DL. Phenotypic diversity in the alpha C protein of group B streptococci. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2638–2644. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2638-2644.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickman ME, Rench MA, Ferrieri P, Baker CJ. Changing epidemiology of group B streptococcal colonization. Pediatrics. 1999;104:203–209. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeland JA, Brakstad OG, Bevanger L, Kvam AI. Streptococcus agalactiae beta gene and gene product variations. J Med Microbiol. 1997;46:999–1005. doi: 10.1099/00222615-46-12-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berner R, Bender A, Rensing C, Forster J, Brandis M. Low prevalence of the immunoglobulin-A-binding beta antigen of the C protein among Streptococcus agalactiae isolates causing neonatal sepsis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18:545–550. doi: 10.1007/s100960050346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore N, Bennett D, Kaliszer M, Cafferkey M, Smyth CJ. Molecular epidemiology of group B streptococci in Ireland: associations between serotype, invasive status and presence of genes encoding putative virulence factors. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;131:823–833. doi: 10.1017/S0950268803008847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning SD, Tallman P, Baker CJ, Gillespie B, Marrs CF, Foxman B. Determinants of co-colonization with group B streptococcus among heterosexual college couples. Epidemiology. 2002;13:533–539. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200209000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss SJ, Manning SD, Tallman P, Baker CJ, Pearlman MD, Marrs CF, Foxman B. Group B Streptococcus colonization in male and nonpregnant female university students: a cross-sectional prevalence study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:184–190. doi: 10.1086/338258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning SD, Foxman B, Pierson CL, Tallman P, Baker CJ, Pearlman MD. Correlates of antibiotic-resistant group B streptococcus isolated from pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:74–79. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaleznik DF, Rench MA, Hillier S, Krohn MA, Platt R, Lee ML, Flores AE, Ferrieri P, Baker CJ. Invasive disease due to group B Streptococcus in pregnant women and neonates from diverse population groups. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:276–281. doi: 10.1086/313665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning SD, Pearlman MD, Tallman P, Pierson CL, Foxman B. Frequency of antibiotic resistance among group B Streptococcus isolated from healthy college students. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:E137–9. doi: 10.1086/324588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Kasper DL, Ausubel FM, Rosner B, Michel JL. Inactivation of the alpha C protein antigen gene, bca, by a novel shuttle/suicide vector results in attenuation of virulence and immunity in group B Streptococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13251–13256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Gillespie B, Marrs CF, Foxman B. Optimization of a fluorescent-based phosphor imaging dot blot DNA hybridization assay to assess Escherichia coli virulence gene profiles. J Microbiol Methods. 2001;44:225–233. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(01)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxman B, Zhang L, Tallman P, Palin K, Rode CK, Bloch CA, Gillespie B, Marrs CF. Virulence characteristics of Escherichia coli causing first urinary tract infection predict risk of second infection. J Infect Dis. 1994;172:1536–1541. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchardt SM, Foxman B, Chaffin DO, Rubens CE, Tallman PA, Manning SD, Baker CJ, Marrs CF. Comparison of DNA dot blot hybridization and lancefield capillary precipitin methods for group B streptococcal capsular typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:146–150. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.146-150.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. The SAS System for Windows. 8e. Cary, NC, ; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Insel RA. Maternal immunization to prevent neonatal infections. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1219–1220. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811033191809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvorov A, Dmitriev A, Ustinovitch I, Schalen C, Totolian AA. Molecular analysis of clinical group B streptococcal strains by use of alpha and beta gene probes. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1997;17:149–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1997.tb01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeland JA, Brakstad OG, Bevanger L, Krokstad S. Distribution and expression of bca, the gene encoding the c alpha protein, by Streptococcus agalactiae. J Med Microbiol. 2000;49:193–198. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-2-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N, Bohnsack JF, Takahashi S, Oliver KA, Chan MS, Kunst F, Glaser P, Rusniok C, Crook DW, Harding RM, Bisharat N, Spratt BG. Multilocus sequence typing system for group B streptococcus. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2530–2536. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2530-2536.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser P, Rusniok C, Buchrieser C, Chevalier F, Frangeul L, Msadek T, Zouine M, Couve E, Lalioui L, Poyart C, Trieu-Cuot P, Kunst F. Genome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae, a pathogen causing invasive neonatal disease. Mol Microbiol. 2002;45:1499–1513. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, Eisen JA, Peterson S, Wessels MR, Paulsen IT, Nelson KE, Margarit I, Read TD, Madoff LC, Wolf AM, Beanan MJ, Brinkac LM, Daugherty SC, DeBoy RT, Durkin AS, Kolonay JF, Madupu R, Lewis MR, Radune D, Fedorova NB, Scanlan D, Khouri H, Mulligan S, Carty HA, Cline RT, Van Aken SE, Gill J, Scarselli M, Mora M, Iacobini ET, Brettoni C, Galli G, Mariani M, Vegni F, Maione D, Rinaudo D, Rappuoli R, Telford JL, Kasper DL, Grandi G, Fraser CM. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12391–12396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182380799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tettelin H, Masignani V, Cieslewicz MJ, Donati C, Medini D, Ward NL, Angiuoli SV, Crabtree J, Jones AL, Durkin AS, Deboy RT, Davidsen TM, Mora M, Scarselli M, Margarit y Ros I, Peterson JD, Hauser CR, Sundaram JP, Nelson WC, Madupu R, Brinkac LM, Dodson RJ, Rosovitz MJ, Sullivan SA, Daugherty SC, Haft DH, Selengut J, Gwinn ML, Zhou L, Zafar N, Khouri H, Radune D, Dimitrov G, Watkins K, O'Connor KJ, Smith S, Utterback TR, White O, Rubens CE, Grandi G, Madoff LC, Kasper DL, Telford JL, Wessels MR, Rappuoli R, Fraser CM. Genome analysis of multiple pathogenic isolates of Streptococcus agalactiae: implications for the microbial "pan-genome". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13950–13955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506758102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]