The Eco-Challenge, organized annually from 1995 to 2002, was a gruelling adventure race in which teams ran, swam, sailed and biked across rugged terrain, often in remote parts of the world. Participants in the 2000 race in Sabah—formerly North Borneo—were prepared to meet many challenges; what they did not anticipate was swimming through a river contaminated with Leptospira, the causative agent of a potentially fatal disease called leptospirosis (Sejvar et al, 2003). One participant developed fever and jaundice after returning to the UK and was diagnosed with leptospirosis by a travel medicine clinic in London. Within 12 hours, messages went out to clinics all across the world to alert them to the possibility of leptospirosis in participants from the Eco-Challenge. Those individuals who were still in the incubation period were notified and treated. This swift and effective response was orchestrated by an international infectious disease-monitoring organization called GeoSentinel. By cataloguing and analysing data on international travellers who report to a travel medicine clinic, GeoSentinel—and a similar European-based initiative called TropNetEurop—aim to develop a comprehensive picture of the spread of infectious diseases as it occurs.

As Tomas Jelinek, from the Berlin Center for Travel & Tropical Medicine, Germany, and coordinator of TropNetEurop, pointed out, travellers are a rich source of information for infectious disease specialists. On returning from their journey, travellers can provide a representative sample of the diseases that abound in the places they have visited. Moreover, a traveller who returns home with an unusual disease could be the first clue to a new outbreak.

…a traveller who returns home with an unusual disease could be the first clue to a new outbreak

GeoSentinel and TropNetEurop tap into this resource by providing a system for sharing information among their networks of travel medicine clinics. Doctors record the travel histories and symptoms of their patients and their diagnoses in standardized electronic forms and submit these by e-mail to a central database. Investigators, including epidemiologists and statisticians, regularly examine the data to detect ‘blips' that might indicate a new outbreak, which would warrant a warning to participating clinics. The database coordinators also look for long-term disease trends, issue regular summaries to their member sites and report some findings in medical journals. Last January, for example, GeoSentinel published an article describing which diseases travellers are most likely to acquire in different parts of the world (Freedman et al, 2006).

There are various national and international bodies that track infectious disease, but GeoSentinel and TropNetEurop are distinctive in several ways. First, they are interested in diseases only in international travellers, not those confined to local populations. This allows them to focus on diseases that have escaped their place of origin and could spread to become a worldwide problem. Second, both organizations use only clinical data—in contrast to epidemiological or laboratory data, which are more time-consuming to acquire—and are therefore able to quickly track a fast-moving disease outbreak. “That's an important thing,” said Jelinek. “[We have] people dealing with patients, touching patients, talking with patients, and we are trying to benefit from this information as much as possible.” Finally, GeoSentinel and TropNetEurop have a very fast response time. Whenever one member site sees an unusual case, they immediately notify the rest of the network through the coordinators. If any other sites have had similar cases, the network can quickly establish a pattern and pinpoint where and when the disease originated. In the case of the Eco-Challenge leptospirosis outbreak, the London clinic that treated the first patient immediately alerted the GeoSentinel network. A few hours later, sites in New York, USA, and Toronto, Canada, reported similar cases. By the end of the day, GeoSentinel had reported the leptospirosis outbreak in several electronic forums and informed public health authorities in the home countries of the participants.

…both organizations use only clinical data … and are therefore able to quickly track a fast-moving disease outbreak

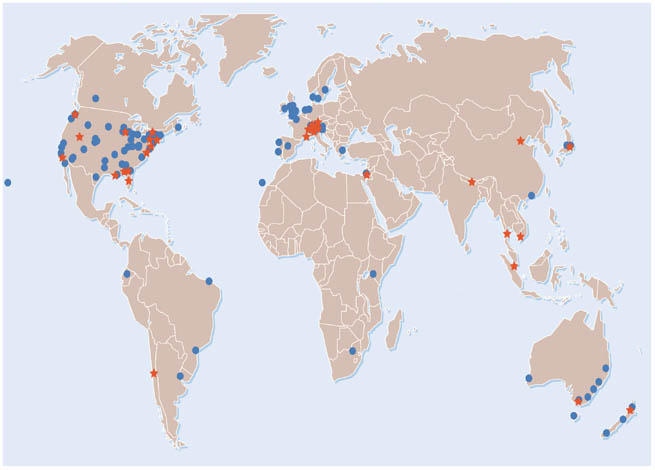

David Freedman from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA, and colleagues in the International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM; Stone Mountain, GA, USA) co-founded GeoSentinel because they wanted a more “rapid and efficient” way to keep abreast of infectious diseases. In 1995, Freedman, Phyllis Kozarsky from Emory University in Atlanta, GA, and Martin Cetron from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; Atlanta) organized a network of nine US travel medicine clinics. After two years of development, GeoSentinel began collecting and analysing data from its member clinics in 1997. Since then it has increased to 33 member sites in North and South America, Europe, Asia and Australia, who report every travel-related illness they see to the central database in Atlanta (Fig 1). In addition, 145 sites around the world participate in the GeoSentinel Network Member programme. These clinics report informally on unusual or alarming cases. The main advantage of having geographically distributed sites, according to Freedman, is that people from different parts of the world have different travel patterns. For example, US tourists are more likely to go to the Caribbean, Europeans to Africa, and Australians to Asia.

The main advantage of having geographically distributed sites … is that people from different parts of the world have different travel patterns

Figure 1.

Locations of GeoSentinel Surveillance Sites (red stars) and Network Members (blue circles).

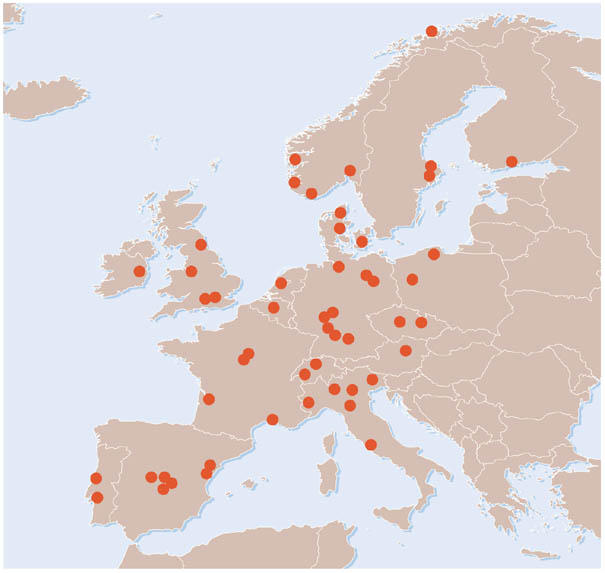

TropNetEurop—also known as the European Network on Imported Infectious Disease Surveillance—was launched in 1999 to fill a critical need for information on diseases imported to Europe. At its start, 24 member clinics from around Europe reported to the central database in Berlin. The number of clinics has since grown to 50 (Fig 2). Initially, it focused on three diseases—malaria, dengue fever and schistosomiasis; it has recently added leishmaniasis to the list. In addition, TropNetEurop's members report whenever they see something they consider to be unusual. “They are experienced clinicians; they have a good grasp of what's normal and what's not normal, and if there is something unusual, they report it immediately by e-mail,” commented Jelinek. Although the two networks do not share the bulk of their data with each other, they communicate whenever they see an unusual case and occasionally publish articles together.

Figure 2.

Locations of TropNetEurop reporting sites.

GeoSentinel and TropNetEurop clinics see a wide variety of travellers ranging from tourists and business people to immigrants, refugees and foreign-born citizens who have visited friends and relatives in their home countries. GeoSentinel sometimes selects new surveillance sites on the basis of their patient populations, said Freedman. For example, Elizabeth Barnett, Associate Professor of Pediatrics at Boston University, MA, USA, sought to join GeoSentinel in the late 1990s because her clinic sees many African refugees. Owing to many factors—including poor nutrition, lack of regular medical care and a lifetime of exposure to infectious diseases in their countries of origin and refuge—refugees often have diseases that are uncommon in tourists, said Barnett.

Although reporting to the networks does entail additional work, GeoSentinel and TropNetEurop members are generally enthusiastic about their participation in monitoring infectious diseases. For Devon Hale, who heads the GeoSentinel site at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, USA, the biggest benefit is the early warning about outbreaks. “We get alerts and then when we see people from [the affected] areas, we look specifically for the kinds of diseases that have been documented recently,” he explained. Ron Behrens, who heads a TropNetEurop surveillance site at the Hospital for Tropical Diseases in London, UK, considers the greatest success of his network to be the commitment of the member clinicians who “give up their own personal time and resources to monitor the health and safety of travellers”.

Both networks have also achieved some more tangible successes. In March 2003, the GeoSentinel site in Toronto saw some of the first cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outside Asia and quickly notified the network that SARS “had boarded an airplane” and was now a global problem, said Freedman. In 1999, TropNetEurop discovered an outbreak of malaria in a region of the Dominican Republic that was thought to be free of the disease. Two years later, they traced an outbreak of African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) to the Serengeti in Tanzania after several tourists returning from the region became ill. On both occasions, there were unreported cases among the local people, and TropNetEurop worked with local health authorities to further control and treat the outbreaks. It also had an important role in treating the European patients, said Jelinek, as member clinics shared medications that were difficult to obtain.

In addition, TropNetEurop uses its analysis of long-term trends to improve public health policy. Recently, they determined that the risk of contracting malaria in India was low enough that it no longer justified the use of preventative anti-malarial drugs, which can have severe side effects. In response, four countries stopped recommending anti-malarial drugs to people travelling to India, and other countries might soon follow, according to Jelinek.

GeoSentinel and TropNetEurop have seen changes in disease patterns in recent years, which might be linked to travel habits. For example, overseas travel by European tourists has increased, and so has the number of dengue fever cases reported by TropNetEurop sites, said Jelinek. TropNetEurop also noted an increase in malaria cases owing to the large influx of immigrants into Europe from regions where the disease is endemic. GeoSentinel reported several disease outbreaks from adventure travels to remote destinations. For example, their sites have reported cases of leishmaniasis in tourists who travelled to Madidi, a new national park in the Bolivian jungle, or who participated in rafting trips in the Costa Rican jungle, said Freedman.

Both networks are also well placed to track occurrences of avian flu, one of the greatest concerns today among public health experts. GeoSentinel, in particular, is in a good position as it has collected data on flu-like illnesses since its creation and now has a firm understanding of where, when and how frequently flu normally occurs, according to Freedman. An avian flu outbreak would cause a significant deviation from this pattern, which GeoSentinel could identify well before a laboratory could make the diagnosis. In anticipation of a possible outbreak, GeoSentinel has increased its monitoring of respiratory illnesses. In addition, the network gained valuable experience during the SARS outbreak. At its peak, GeoSentinel shifted into high gear, updating its analysis of respiratory disease at least once a week and sending bulletins to scientists and clinicians, including all 2,000 members of the ISTM.

Both networks are also well placed to track occurrences of avian flu, one of the greatest concerns today among public health experts

TropNetEurop also regards avian flu as a case that would merit immediate reporting to the network. However, TropNetEurop has not routinely tracked flu-like illnesses in the past and does not have the resources to start now, Behrens commented. “We're keen to contribute,” he said, but a significant increase in flu surveillance would require more money and manpower. Right now, he continued, “we are running at our maximum on the few diseases that we currently monitor”.

Jelinek and Behrens stressed that the biggest challenge facing TropNetEurop in the future is the lack of secure funding. It is a private organization with no ties to any European government, and it relies entirely on the goodwill of its members. “This is one of the weaknesses [of TropNetEurop],” said Behrens, “but it is also one of the strengths in the sense that everybody who [participates] is committed to doing it for the benefit of everybody else.” Jelinek and Behrens are hopeful that they might eventually receive support from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control in Solna, Sweden. Until then Behrens fears that TropNetEurop will continue to be “vulnerable to pressures of time and resources”.

GeoSentinel has better financial security, thanks to support from the CDC and the ISTM, but it has experienced some growing pains as it expands its international reach. Some countries are nervous about having a GeoSentinel site because they are concerned that it will disrupt reporting to their national health authorities. “All of our sites sign an agreement that no obligation to report to GeoSentinel supersedes their obligation to report…to the appropriate public health authorities within their own countries,” Freedman said. GeoSentinel reports informally to the World Health Organization (WHO; Geneva, Switzerland), as does TropNetEurop, but the WHO has been reluctant to establish closer ties. As Jelinek put it, “whether [the WHO] acts on [the networks' information] or what they do with it is left to them.” The WHO's main mission, said Freedman, is to work with national health authorities and it does not want to become too involved with organizations that might be perceived as bypassing those authorities.

The CDC, by contrast, has collaborated closely with GeoSentinel from the beginning. In fact, the central database of the network is located at the CDC headquarters in Atlanta, although it is maintained by GeoSentinel employees. The CDC has both received information from GeoSentinel and used its network to relay news about urgent situations to the infectious disease community. “Having a network of travel clinics around the world that are linked with rapid communication is really a vital asset to be able to tap into,” said Paul Arguin, Chief of the Domestic Response Unit in the CDC's Malaria Branch. He believes that health authorities, particularly in smaller countries, could benefit from GeoSentinel's surveillance because it pools data from around the world and makes it possible to detect outbreaks that might not be obvious from looking at isolated cases within a single country.

Others in the infectious disease community agree. Herbert DuPont, Director of the Center for Infectious Diseases at the University of Texas's Health Science Center (Houston, USA), calls GeoSentinel and TropNetEurop “terrific programs and the right step towards near real-time surveillance. They are early in their development and need time and additional sites to be the best they can be.”

References

- Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, Fisk T, Robins R, von Sonnenburg F, Keystone JS, Pandey P, Cetron MS; GeoSentinel Surveillance Network (2006) Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med 354: 119–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sejvar J et al. (2003) Leptospirosis in “Eco-Challenge” Athletes, Malaysian Borneo, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis 9: 702–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]