When health officials unveiled a case definition for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) recently, it was supposed to help MDs decide if patients had a disease for which there was no test.

But the comprehensive list of symptoms, which include fever and a dry cough, posed a unique problem in Toronto's already stressed ERs. How could they diagnose SARS in pediatric patients who could not tell them about their symptoms?

“Ultimately, we're faced with gazillions of kids with runny noses, fevers and coughs from any of a variety of non-SARS sources,” explained Dr. Bruce Minnes, associate clinical chief of emergency medicine at the Hospital for Sick Children. “So when should we have a higher suspicion?”

In the absence of a suitable test, said Minnes, doctors at Toronto's 15 emergency departments and 5 SARS assessment clinics started relying on a combination of symptoms and background information provided by a parent.

Information about travel to affected countries, or exposure to an affected community within Toronto, raised a red flag. “With any kid who has the usual mild respiratory symptoms or fever, contact screening is our tool for identifying someone who may be at risk.”

When young patients show additional severe respiratory symptoms and higher fevers, doctors automatically began treating them as SARS patients. “We would err on the side of caution, because we obviously don't have a tool for making a positive diagnosis.”

This means that children showing symptoms will be more likely to undergo mandatory 10-day isolation than adults, but Dr. Tim Rutledge defended such moves. “We want to be really careful,” explained the medical director of emergency services at the North York General Hospital. “Specifically, with children and the frail elderly the presentation can be more subtle, and therefore we have to be even more hypervigilant.”

Rutledge estimates that children have accounted for 20% of the suspected or probable SARS cases at his hospital. Global experience has shown that while these pediatric diagnoses are harder to make, most fatalities occur in older patients. Of Toronto's 23 SARS deaths up to May 1, none of the patients has been under 39, and most have been older than 70. “It definitely seems to be a less severe illness in children,” Rutledge said.

He said MDs should look for a combination of symptoms and test results before isolating a child; the most useful signal from the physical exam is a temperature above 38° C. Both doctors said the prospect of placing an infant or toddler in quarantine is stressful. “It's not a great position to be in,” said Minnes. — Brad Mackay, Toronto

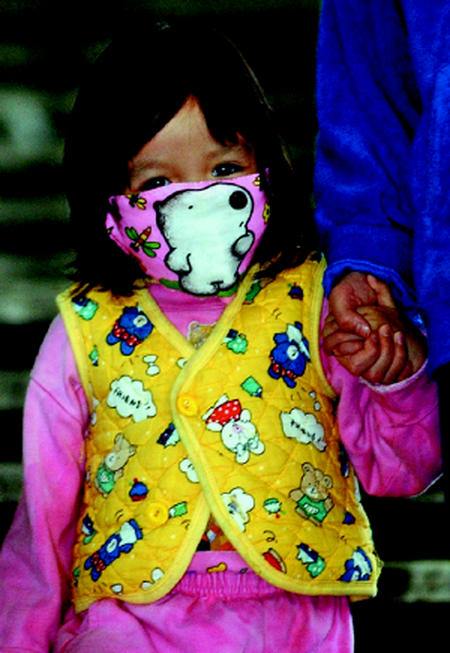

Figure. Children: Best to err on the side of caution Photo by: Canapress