Abstract

Background: Edaravone had been validated to effectively protect against ischemic injuries. In this study, we investigated the protective effect of edaravone by observing the effects on anti-apoptosis, regulation of Bcl-2/Bax protein expression and recovering from damage to mitochondria after OGD (oxygen-glucose deprivation)-reperfusion. Methods: Viability of PC12 cells which were injured at different time of OGD injury, was quantified by measuring MTT (2-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) staining. In addition, PC12 cells’ viability was also quantified after their preincubation in different concentration of edaravone for 30 min followed by (OGD). Furthermore, apoptotic population of PC12 cells that reinsulted from OGD-reperfusion with or without preincubation with edaravone was determined by flow cytometer analysis, electron microscope and Hoechst/PI staining. Finally, change of Bcl-2/Bax protein expression was detected by Western blot. Results: (1) The viability of PC12 cells decreased with time (1~12 h) after OGD. We regarded the model of OGD 2 h, then replacing DMEM (Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium) for another 24 h as an OGD-reperfusion in this research. Furthermore, most PC12 cells were in the state of apoptosis after OGD-reperfusion. (2) The viability of PC12 cells preincubated with edaravone at high concentrations (1, 0.1, 0.01 μmol/L) increased significantly with edaravone protecting PC12 cells from apoptosis after OGD-reperfusion injury. (3) Furthermore, edaravone attenuates the damage of OGD-reperfusion on mitochondria and regulated Bcl-2/Bax protein imbalance expression after OGD-reperfusion. Conclusion: Neuroprotective effects of edaravone on ischemic or other brain injuries may be partly mediated through inhibition of Bcl-2/Bax apoptotic pathways by recovering from the damage of mitochondria.

Keywords: Edaravone, Ischemia, Apoptosis, Rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells, Mitochondria, Bax, Bcl-2, Oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD)

INTRODUCTION

The incidence ischemia rised rapidly with the increasing number of the aging population increasing in the modern society. Although more and more studies demonstrate the ischemia mechanism, such as excessive production of free radicals (Chung et al., 2006; Margaill et al., 2005), altered calcium homeostasis (Montell, 2005) and N-methyl-D-aspartate excitotoxicity (Christophe and Nicolas, 2006), few effective therapeutic drugs have been used in clinic.

Excessive production of free radicals has been implicated to accelerate the development of brain edema and secondary brain delay damage after ischemia (Caccamo et al., 2004). Several investigators also have proposed a possible involvement of free radicals in the pathobiology of neurons apoptosis (Nagashima et al., 2000). Both animal and cellular experiments showed that most antioxidant therapies were helpful for neurons survival (Noor et al., 2005), but few have shown any beneficial effects in clinical trials, despite their excellent efficiencies in animal models (Won et al., 2002). Edaravone had been clinically prescribed in Japan since 2001 to treat patients with cerebral ischemia (Okatani et al., 2003; Takuma et al., 2003).

Edaravone (2-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one, MCI-186) is free-radial scavenger that has been evaluated as a neuroprotective compound which reduces the increase of hydroxyl radical and superoxide anion level in several models of cerebral ischemia (Hoehn et al., 2003; Okatani et al., 2003). Using a rat model of transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), the data showed that daily treatment with edaravone reduced cortical infarction volume. In addition, edaravone not only has antioxident action, but also protects cells from apoptosis (Kokura et al., 2005; Suzuki et al., 2005). However, little information is available on antioxidant edaravone in regulating the Bcl-2/Bax apoptotic pathway via mitochondria after OGD-reperfusion injury at cellular level.

In vitro ischemic-like injury is usually induced by oxygen-glucose deprivation (OGD) in neurons (Iijima et al., 2003). Rat pheochromocytoma cells (PC12 cells) have also been used in studies of in vitro ischemia injury (Zhou et al., 2001). Our research showed that edaravone is a very safe and effective neuroprotective drug against ischemia. Edaravone protects PC12 cells from apoptosis resulting from the injury of OGD-reperfusion. Furthermore, edaravone slightly increases Bcl-2 protein and significantly suppresses Bax protein via recovering from mitochondria damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

PC12 cells were purchased from the Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai) and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Sigma, USA), supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS, Sigma, USA), 10% heat-inactivated horse serum, penicillin (50 U/ml), streptomycin (50 mg/L). Before OGD and edaravone (Mitsubishi Chemical Industries, Japan) addition, cultures were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.0, and detached with 0.25% trypsin (Sigma, USA), then centrifuged and subcultured in a poly-L-lysine-coated 96-well microtiter plate, 5×105 cells/ml, 100 μl in each well. PC12 cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Oxygen-glucose deprivation

Next day, the PC12 cells were treated by OGD as described previously (Zhou et al., 2001). Briefly, the original media were removed; the cells were washed with a glucose-free Earle’s balanced salt solution (EBSS) at pH 7.4 and placed in fresh glucose-free EBSS. The cultures were then introduced into an incubator containing a mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% N2 at 37 °C for 2 h and DMEM was replaced for another 24 h as OGD-reperfusion model. The control culture was maintained in normal EBSS and put in the incubator under normal conditions. Edaravone was added to the culture 30 min before OGD treatment.

Cell viability analysis

Cellular viability was evaluated by the reduction of 2-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) to formazan. MTT was dissolved in PBS, and added to the culture at final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. After an additional 2 h incubation at 37 °C, the media were carefully removed and 100 μl DMSO was added to each well, and the absorbance at 490 nm of MTT products formazan was measured on a platereader (ELX 800, BIO-TEK). Results were expressed as percentages of control.

Hoechst 33258/PI staining

Cell death was determined by propidium iodide (PI) and Hoechst 33258 double fluorescent staining. PC12 cells were cultured on cover slides. After injury by OGD for 2 h and followed by 24 h recovery, the cells were stained with PI (10 μg/ml) and Hoechst 33258 (10 μg/ml, Sigma, USA) and then fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde. For each cover slide, 1000~1500 cells were examined under a fluorescence microscope (Olympus BX51, Japan) and photographed with a digital camera (Olympus DP70, Japan). The results were expressed as the percentages of apoptotic cells and necrotic cells, respectively.

Electron microscope

PC12 cells were seeded at 1×10 6 cells/ml in 250 ml flasks and grown until 90% density. Cells were treated with OGD for 2 h, then replaced with DMEM for 24 h. For ultrastructural examination, cells were fixed with 0.2 mol/L glutaraldehyde and osmium tetroxide, and embedded into epon by standard procedures. Ultra-thin sections were cut, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and studied with an electron microscope (Philips, CM10, Lyon 1 Microscopy Center Lyon, France).

Flow cytometer analysis

PC12 cells were injured by OGD-reperfusion in the absence or presence of edaravone (0.1 μmol/L) for 2 h and reperfusion. The population of apoptotic cells was quantified by annexing V-FITC (Bender Medsystems, Boehringer Mannheim, Germany) staining. Briefly, 5×106 PC12 cells were washed in PBS and resuspended in 200 μl binding buffer (BB), containing 10 mmol/L Hepes/NaOH pH 7.4, 140 mmol/L NaCl and 2.5 mmol/L CaCl2, plus 0.6 μl of annexin V-FITC kit and incubated for 20 min at room temperature in the dark. After incubation, we added 200 μl BB and propidium iodide (PI) to final concentration of 5 μg/ml. Cells were analyzed using a flow cytometer (EPICS-XL, Coulter, CA). Samples were acquired and analyzed using cell Quest software and data were analyzed with software.

Western blot analysis

Equal amounts of protein (50 μg) were separated on 12% SDS/PAGE gels for detection of Bcl-2/Bax expression, then respectively transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with nonfat milk and incubated with the primary antibody (polyclonal anti-Bcl-2/Bax antibody, 1:100, Santa Cruz, USA) overnight. Immunological complexes were revealed with an anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated (1:1000, Santa Cruz, USA) in blocking buffer for 1 h at room temperature and washed again in TBST (Tris-Buffered Saline Tween-20), detection of signal was performed with chemiluminescence and exposed by film.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean±SD. Statistical comparisons were made by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Values of * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Effect of edaravone on OGD-reperfusion cytotoxicity

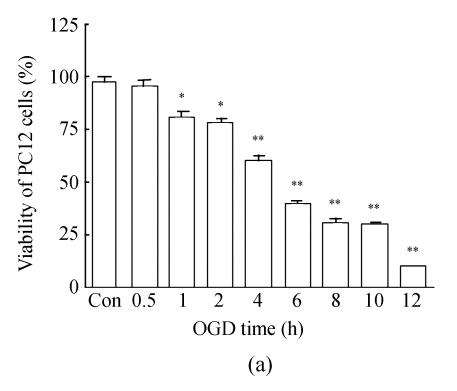

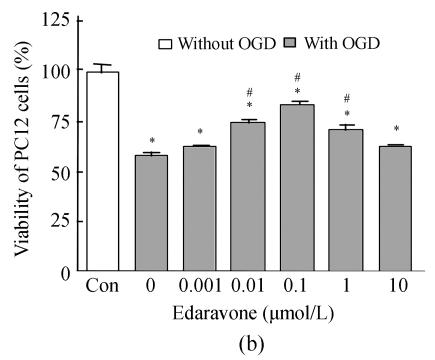

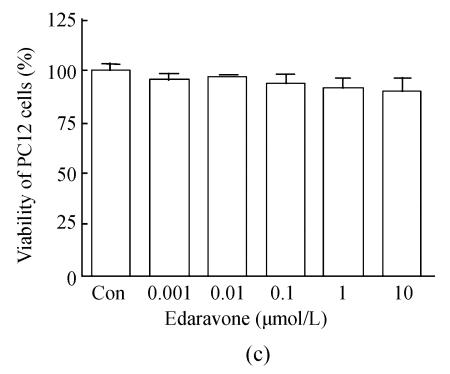

Determination of the damage was performed by measuring the MTT reduction ability of PC12 cells. OGD-reperfusion decreased the viability of PC12 cells in a time-dependent manner; the time ranged from 1 h to 12 h (Fig.1a). The cell viability was slight reduced by about 15% and cell morphology was mildly altered at OGD 2 h. Furthermore, the pO2 in medium decreased from (152±5) mmHg to (29±1) mmHg (n=5, P<0.01), and the glucose was almost zero (data not shown) after OGD 2 h. We used OGD 2 h and replaced DMEM for another 24 h as an injury reperfusion model in the following experiments. The viability of PC12 cells was significantly decreased after OGD 2 h and reperfusion for 24 h (Fig.1b).

Fig. 1.

Time-dependent damage of OGD-reperfusion on PC12 cells and edaravone protective effect on OGD-reperfusion. (a) OGD reduced the cell viability in time-dependent; (b) Edaravone protected PC12 cells from OGD-reperfusion in a concentration-dependent manner; (c) Edaravone did not show any toxin on PC12 cells

Data are expressed as mean±SD; n=12 wells for each group; * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01, compared to control; # P<0.05, compared to OGD-reperfusion (one-way ANOVA)

As shown, comparative high concentration edaravone (1, 0.1, 0.01 μmol/L) induced a increase of cell survival in a manner of concentration-dependent (Fig.1b). In addition, whatever high concentration of edaravone didn’t show any toxin for PC12 cells (Fig.1c).

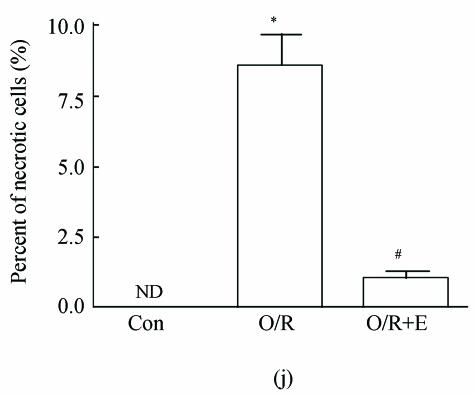

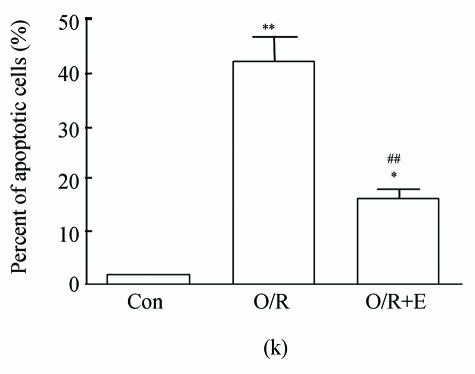

Morphological analysis of PC12 cells death

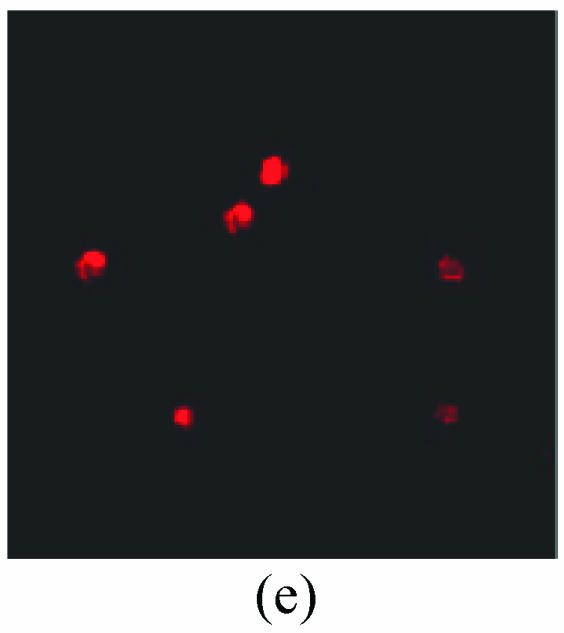

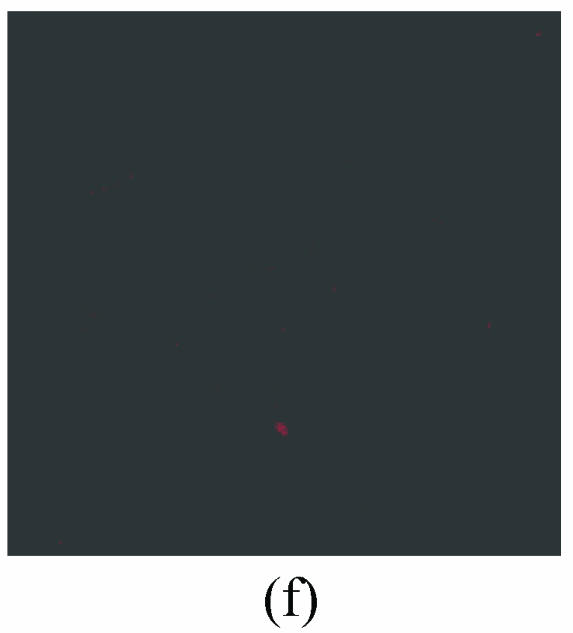

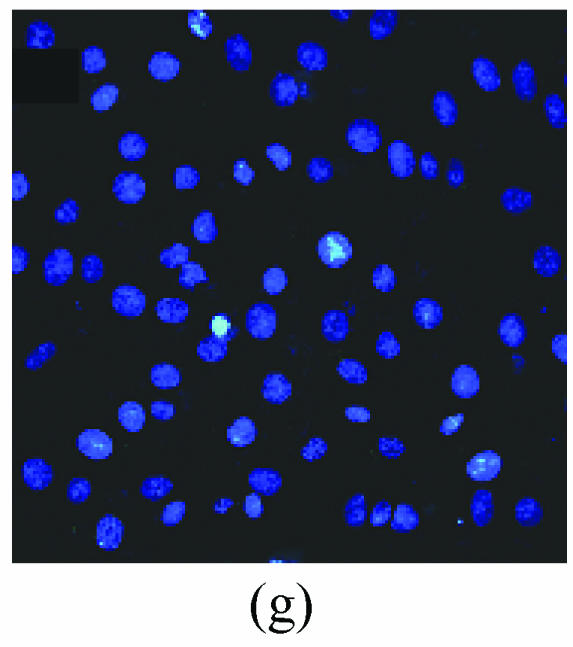

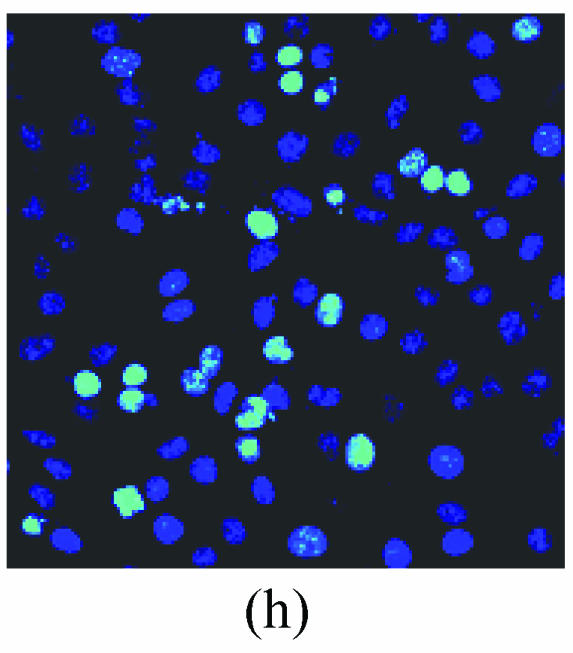

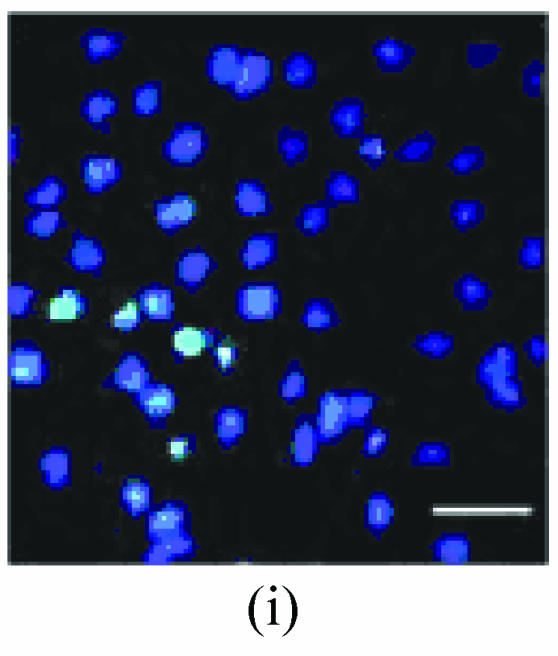

As shown in picture, PC12 cells growed as ellipse in the pattern of cluster. After nerve growth factor (NGF) induced, PC12 cells brought up the neurite outgrowth (Fig.2a). Once PC12 injury by OGD-reperfusion, even cells became round, breaking off their outgrowth, and lost their normal morphological, detachment to die (Fig.2b). If edaravone were administered 30 min before the OGD-reperfusion treatment, PC12 cells damage could attenuate (Fig.2c). From Hoechst/PI staining, control groups were not any necrotic cells (Fig.2d), but only little apoptotic cells (Fig.2g). However, almost 40% PC12 cells shown the apoptotic character, while about 7% PC12 cells were necrotic after OGD-reperfusion (Figs.2h and 2e). Furthermore, the number of apoptotic PC12 cells decreased to 14% and only 1% necrotic cells appeared if preincubation in 0.1 μmol/L edaravone before OGD-reperfusion (Figs.2i and 2f).

Fig. 2.

The protective effects of edaravone on OGD-reperfusion induced PC12 cell death by Hoechst 33258/PI staining. The cell death was analyzed by double fluorescent staining with Hoechst 33258 and propidium iodide (PI). (a) Con, (b) O/R, (c) O/R+E: Under microscopes; (d) Con, (e) O/R, (f) O/R+E: The representative microphotographs show the necrotic cells as detected by PI staining after OGD-reperfusion induced injury; (g) Con, (h) O/R, (i) O/R+E: The representative microphotographs show the apoptotic cells as detected by Hoechst 33258 staining after OGD-reperfusion induced. However, edaravone (0.1 μmol/L) prevented PC12 cells from OGD-reperfusion injury; (j)~(k) The summarized data show percentage changes in the numbers of necrotic (j) and apoptotic (k) cells

Data are expressed as mean±SD; n=4 wells for each group; * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01, compared to control; # P<0.05 and ## P<0.01, compared to OGD alone (one-way ANOVA). Con: Control; O/R: OGD 2 h and reperfusion 24 h; O/R+E=OGD-reperfusion+edaravone (0.1 μmol/L). Scale bar=20 μm

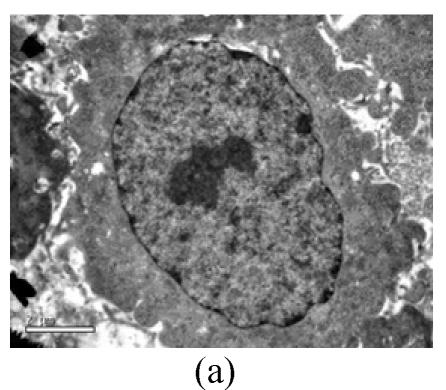

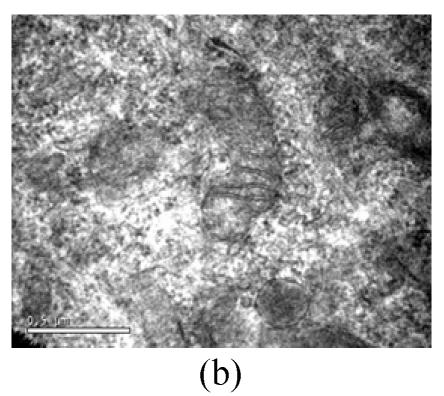

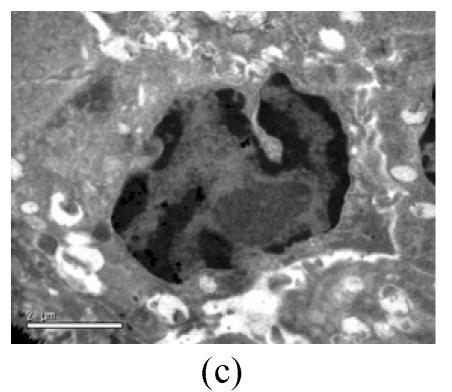

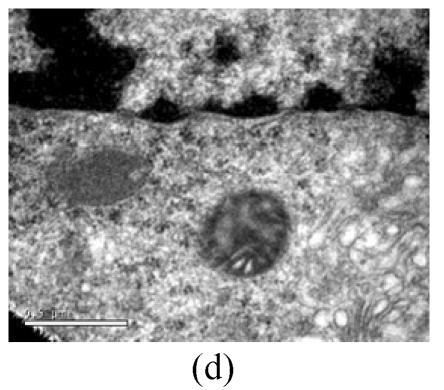

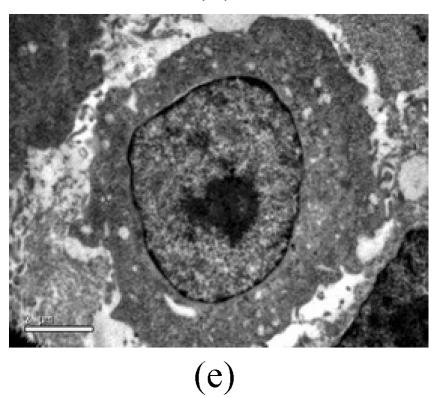

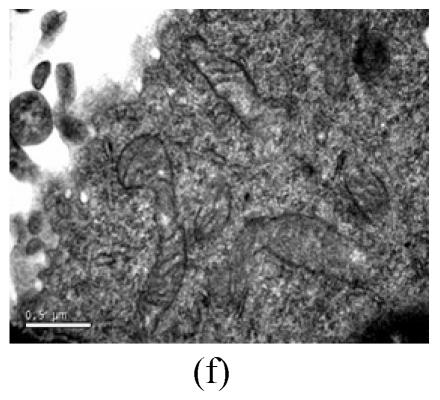

Electron microscopy

To evaluate the mode of cell death induced by OGD reperfusion, we performed ultrastructural examination of PC12 cells which were fixed after treatment with OGD-reperfusion and observed under electron microscopy. Cells subjected to injury had typical apoptotic characteristics morphologically: strong condensation of heterochromatin and congregated to edge of nuclear membranes. Furthermore, cells’ nucleus shrank and vacuolated with intact plasma membranes (Fig.3b), in contrast to control cells (Fig.3a). Most PC12 cells preincubated with edaravone (0.1 μmol/L) retained normal nucleus morphology (Fig.3c). As shown, most of the mitochondria from the control group were in a highly condensed form. The matrix was tightly packed and rather board-like concentrated distribution (Fig.3d). However, the mitochondria from OGD groups lost their swelling-contraction cycle and appeared in shrunken state (Fig.3e). In contrast, in mitochondria from edaravone-administered group, most PC12 cells were in a relatively normal state (Fig.3f).

Fig. 3.

Effects of edaravone on OGD-reperfusion by electron microscope. (a) Normal feature of PC12 cells showed clear intact nuclear; (b) Normal mitochondria of PC12 cells; (c) After OGD-reperfusion insult, PC12 cell’s nuclear’s heterochromatin condensed and congregated to nuclear’s membranes; (d) After OGD-reperfusion insult, PC12 cell’s mitochondria’s condensed and its matrix disappeared; (e) If preincubated with edaravone (0.1 μmol/L), PC12 cells maintained normal nuclear’s morphology; (f) If preincubated with edaravone (0.1 μmol/L), PC12 cells maintained normal mitochondria’s morphology. Bar=0.5 μm

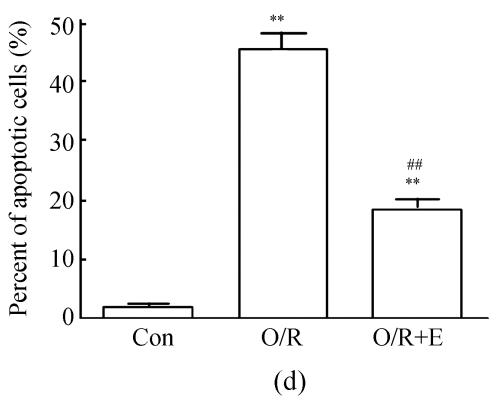

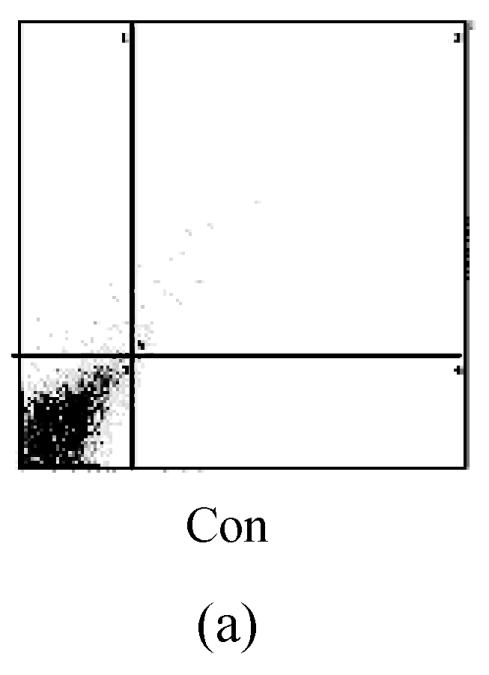

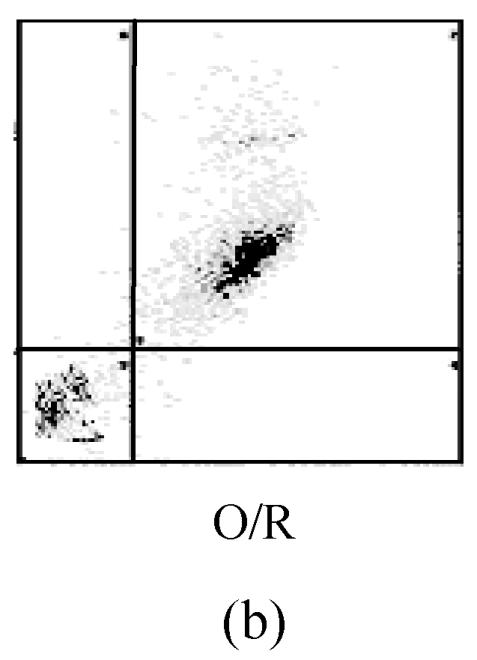

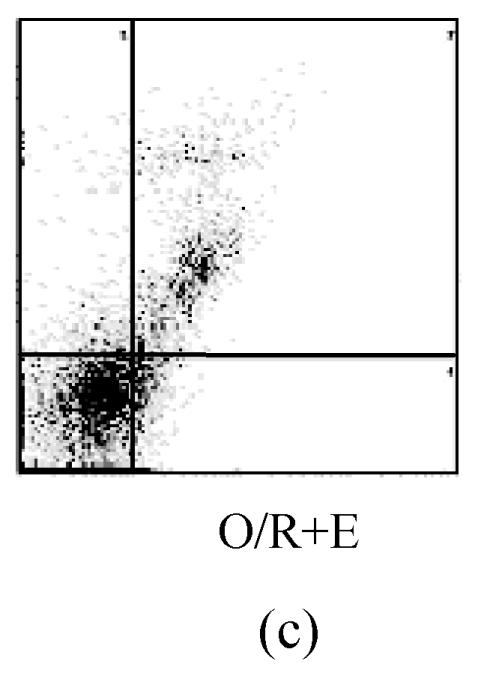

Flow cytometer analysis

The values of the apoptotic populations which in normal group and OGD-reperfusion result group were (1.5±0.143)% and (46±3.287)% respectively (Fig.4b). The mean values of the apoptotic population decreased down to (20±2.543)%. These results demonstrated that edaravone partly inhibited the apoptosis of PC12 cells after OGD-reperfusion injury.

Fig. 4.

Effects of edaravone on OGD-reperfusion by flow cytometer. (a)~(c) The representative figure show the apoptotic cells as detected by flow cytometer after OGD-induced injury; (d) The summarized data show apoptotic cells’ percentage changes by flow cytometer

Data are expressed as mean±SD; n=4 wells for each group; ** P<0.01, compared to control; ## P<0.01, compared to OGD-reperfusion alone (one-way ANOVA). Con: Control; O/R: OGD 2 h and reperfusion 24 h; O/R+E=OGD-reperfusion+edaravone (0.1 μmol/L)

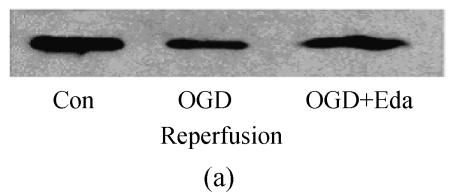

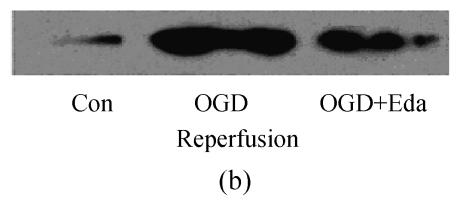

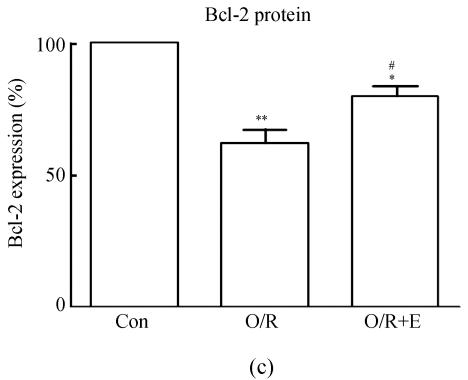

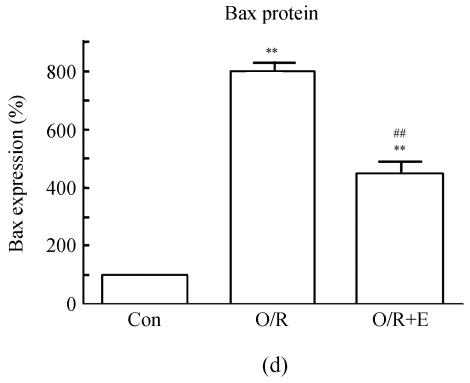

Expression of Bcl-2/Bax under OGD-induced injury

To study the molecular mechanisms of how edaravone prevent apoptosis after OGD-reperfusion was induced, we focused on the expression of Bcl-2 and Bax protein. Bax protein was significantly increased about 8-fold in the PC12 after OGD-reperfusion induced injury, while the Bcl-2 protein slightly decreased. However, the protein of Bcl-2 increased and Bax was suppressed if edaravone was administered before OGD (Fig.5).

Fig. 5.

Effects of edaravone on Bcl-2/Bax protein expression after OGD-reperfusion by Western blot analysis. (a)~(b) The representative photographs showing the Bcl-2 (a)/Bax (b) protein as detected by Western blot after OGD-induced injury; (c)~(d) The summarized data showing Bcl-2 (c)/Bax (d) protein expression percentage changes by Western blot

Data are expressed as mean±SD; n=3 for each group; * P<0.05 and ** P<0.01, compared to control; # P<0.05 and ## P<0.01, compared to OGD-reperfusion alone (one-way ANOVA). Con: Control; O/R: OGD 2 h and reperfusion 24 h; O/R+E=OGD-reperfusion+edaravone (0.1 μmol/L)

DISCUSSION

It is widely accepted that excessive free-radical contributes to neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease (Reddy, 2006), Huntington’s disease (Stoy et al., 2005), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Orrell et al., 2005). Our studies confirmed that OGD is toxic to PC12 cells in time-dependent pattern from 1 h to 12 h. PC12 cells died to almost 15% of total after OGD for 2 h and reperfusion for 24 h as indicated by MTT. To observe edaravone’s effect on apoptosis, we applied comparatively slight injury, in which PC12 cells suffered OGD for 2 h and reperfusion for another 24 h, as an OGD-reperfusion model. In addition, edaravone, an antioxidant, can resume PC12 cells from OGD assault, which of surviving cells almost reaching 80%. These results indicated that the toxicity of free radicals produced by OGD-reperfusion might be one of the important factors for OGD. Furthermore, our results showed that edaravone is a relatively more potent neuroprotective compound for preventing PC12 cells from OGD-reperfusion damage.

The mode of most PC12 cells death is apoptosis, whose character of formation had been proved by flow cytometeric analysis, electron microscope and Hoechst/PI staining after OGD-reperfusion. However, edaravone significantly attenuating the damage of PC12 cells and decrease the number of apoptotic cells. Although much data demonstrate that edaravone do not directly inhibit the activity of caspase-1 and caspase-2 (Yasuoka et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2005), the neuroprotective effects might result from interference with upstream of caspase activation.

Two pathways of apoptosis that have been clearly identified are the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways. The extrinsic pathway is initiated as an extracellular assault, which is dependent on caspase-8 activation (Ceccatelli et al., 2004). The intrinsic pathway is activation associating Bcl-2 protein and Bax protein imbalance expression. Once the cells’ mitochondria are damage after injury, Bax protein on mitochondria increased significantly, resulting in the release of mitochondrial apoptotic factors that activate the effector of caspases, such as caspase-2 and caspase-8 (Perier et al., 2005). On the other hand, Bcl-2 protein is known as an apoptosis inhibitor, and can withstand the effect of Bax protein. Experimental evidence suggests that Bcl-2 protein must be in equilibrium with Bax protein in most cells. Drugs stabilize this equilibrium at a fine balance between Bcl-2 and Bax, which sustained cell survival, or shift the equilibrium toward free Bax, which induced apoptosis. Mitochondria play a crucial role in regulating cell death, which is mediated by outer membrane permeabilization in response to induce the release of cytochrome c, Smac/DIABLO, and AIF, which are regulated by proapoptotic and antiapoptotic proteins such as Bax/Bak and Bcl-2/xL in caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptosis pathways. The genomic responses in intracellular molecular changes after DNA damage are controlled and amplified in the cross-signaling via mitochondria; such signals induce apoptosis, autophagy, and other cell death pathways (Kim et al., 2006; Soane and Fiskum, 2005; Gross, 2005).

Recently, to prove edaravone prevents apoptosis, most researches were performed on animal model (Amemiya et al., 2005; Dong et al., 2004; Rajesh et al., 2003), and edaravone delaying apoptosis has been confirmed. But few experiments on cellular level were reported on the removal an obstacle from blood vessels and circulatory system. Our research suggested that edaravone regulated Bcl-2/Bax protein imbalance expression resulting in OGD-reperfusion on PC12 cells by suppressing the Bax protein overexpression and increasing the Bcl-2 protein. On the other hand, edaravone repaired the damage of PC12 cells’ mitochondria, providing adequate ATP nourishing cells. Furthermore, edaravone decreased Bax protein releasing from mitochondria, which is one of the apoptogenic factors connecting with the apoptosis protein-activating factor-1 (Apaf-1) and caspase-9 to form an apoptosome. All of these activated caspase pathway and accelerated cell apoptosis.

In summary, our results extended edaravone neuroprotective mechanism, to determine that edaravone protects PC12 cells from apoptosis through attenuating the damage of mitochondria. Thus, edaravone provides adequate ATP for cell, and suppresses the Bax protein overexpression, elevating the Bcl-2 protein expression on the critical hinge for apoptosis, inhibits the molecular pathway upstream of caspase.

Footnotes

Project (No. 2005C30059) supported by the Science and Technology Program of Zhejiang Province, China

References

- 1.Amemiya S, Kamiya T, Nito C, Inaba T, Kato K, Ueda M, Shimazaki K, Katayama Y. Anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective effects of edaravone following transient focal ischemia in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;516(2):125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caccamo D, Campisi A, Curro M, Li VG, Vanella A, Ientile R. Excitotoxic and post-ischemic neurodegeneration: involvement of transglutaminases. Amino Acids. 2004;27(3-4):373–379. doi: 10.1007/s00726-004-0117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ceccatelli S, Tamm C, Sleeper E, Orrenius S. Neural stem cells and cell death. Toxicol Lett. 2004;149(1-3):59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.12.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Christophe M, Nicolas S. Mitochondria: a target for neuroprotective interventions in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(6):739–757. doi: 10.2174/138161206775474242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung TW, Koo BS, Choi EG, Kim MG, Lee IS, Kim CH. Neuroprotective effect of a chuk-me-sun-dan on neurons from ischemic damage and neuronal cell toxicity. Neurochem Res. 2006;31(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11064-005-9264-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong J, Takami Y, Tanaka H, Yamaguchi R, Guo JP, Qing C, Lu SL, Shimazaki S, Ogo K. Protective effects of a free radical scavenger, MCI-186, on high-glucose-induced dysfunction of human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Wound Repair Regen. 2004;12(6):607–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1067-1927.2004.12607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gross A. Mitochondrial carrier homolog 2: a clue to cracking the bcl-2 family riddle. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37(3):113–119. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-6222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoehn B, Yenari MA, Sapolsky RM, Stemberg GK. Glutathione peroxidase overexpression inhibits cytochrome C release and proapoptotic mediators to protect neurons from experimental stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(10):2489–2494. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000091268.25816.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iijima T, Mishima T, Akagawa K, Iwao Y. Mitochondrial hyperpolarization after transient oxygen-glucose deprivation and subsequent apoptosis in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2003;993(1-2):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim R, Emi M, Tanabe K. Role of mitochondria as the gardens of cell death. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57(5):545–553. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0111-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kokura S, Yoshida N, Sakamoto N, Ishikawa T, Takagi T, Higashihara H, Nakabe N, Handa O, Naito Y, Yoshikawa T. The radical scavenger edaravone enhances the anti-tumor effects of CPT-11 in murine colon cancer by increasing apoptosis via inhibition of NF-kB. Cancer Lett. 2005;229(2):223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JH, Park SY, Lee WS, Hong KW. Lack of antiapoptotic effects of antiplatelet drug, aspirin and clopidogrel, and antioxidant, MCI-186, against focal ischemic brain damage in rats. Neurol Res. 2005;27(5):483–492. doi: 10.1179/016164105X17134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margaill I, Plotkine M, Lerouet D. Antioxidant strategies in the treatment of stroke. Free Radical Biol Med. 2005;39(4):429–443. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montell C. The latest waves in calcium signaling. Cell. 2005;122(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagashima T, Wu S, Ikeda K, Tamaki N. The role of nitric oxide in reoxygenation injury of brain microvascular endothelial cells. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2000;76:471–473. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6346-7_98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noor JI, Ikeda T, Ueda Y, Ikenoue T. A free radical scavenger, edaravone, inhibits lipid peroxidation and the production of nitric oxide in hypoxic-ischemic brain damage of neonatal rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1703–1708. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okatani Y, Wakatsuki A, Enzan H, Miyahara Y. Edaravone protects against ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative damage to mitochondria in rat liver. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;465(1-2):163–170. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01463-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orrell RW, Lane RJ, Ross M. Antioxidant treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/motor neuron disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;25(1):CD002829. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002829.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perier C, Tieu K, Gueggan C, Caspersen C, Jackson-Lewis V, Carelli V, Martinuzzi A, Hirano M, Przedborski S, Vila M. Complex I deficiency primes Bax-dependent neuronal apoptosis through mitochondrial oxidative damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(52):19126–19131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508215102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajesh KG, Sasaguri S, Suzuki R, Maeda H. Antioxidant MCI-186 inhibits mitochondrial permeability transition pore and upregulates Bcl-2 expression. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285(5):H2171–H2178. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00143.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy PH. Amyloid precursor protein-mediated free radicals and oxidative damage: implications for the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2006;96(1):1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soane L, Fiskum G. Inhibition of mitochondrial neural cell death pathways by protein transduction of bcl-2 family proteins. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2005;37(3):179–190. doi: 10.1007/s10863-005-6590-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stoy N, Mackay GM, Forrest CM, Christofides J, Egerton M, Stone TW, Darlington LG. Tryptophan metabolism and oxidative stress in patients with Huntington’s disease. J Neurochem. 2005;93(3):611–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki K, Kazui T, Terada H, Umemura K, Ikeda Y, Bashar AH, Yamashita K, Washiyama N, Suzuki T, Ohkura K, et al. Experimental study on the protective effects of edaravone against ischemic spinal cord injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130(6):1586–1592. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takuma K, Kiriu M, Mori K, Lee E, Enomoto R, Baba A, Matsuda T. Roles of cathepsins in reperfusion-induced apoptosis in cultured astrocytes. Neurochem Int. 2003;42(2):153–159. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0186(02)00077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Won SJ, Kim DY, Gwag BJ. Cellular and molecular pathways of ischemic neuronal death. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;35(1):67–86. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2002.35.1.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasuoka N, Nakajima W, Ishida A, Takada G. Neuroprotection of edaravone on hypoxic-ischemic brain injury in neonatal rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2004;151(1-2):129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.devbrainres.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou J, Fu Y, Tang XC. Huperzine A protects rat pheochromocytoma cells against oxygen-glucose deprivation. Neuroreport. 2001;12(10):2073–2077. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107200-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]