Abstract

NXF1, p15 and UAP56 are essential nuclear mRNA export factors. The fraction of mRNAs exported by these proteins or via alternative pathways is unknown. We have analyzed the relative abundance of nearly half of the Drosophila transcriptome in the cytoplasm of cells treated with the CRM1 inhibitor leptomycin-B (LMB) or depleted of export factors by RNA interference. While the vast majority of mRNAs were unaffected by LMB, the levels of most mRNAs were significantly reduced in cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56. The striking similarities of the mRNA expression profiles in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns show that these proteins act in the same pathway. The broad effect on mRNA levels observed in these cells indicates that the functioning of this pathway is required for export of most mRNAs. Nonetheless, a set of mRNAs whose export was unaffected by the depletions and some requiring NXF1:p15 but not UAP56 were identified. In addition, our analysis revealed a feedback loop by which a block to mRNA export triggers the upregulation of genes involved in this process.

Keywords: CRM1/mRNA export/nuclear export/NXF1/UAP56

Introduction

Fully processed mRNAs are exported from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where they direct protein synthesis. Within the past few years, factors implicated in this process have been identified through genetic and biochemical experiments in yeast, fruit fly, frog oocytes and human cells. Among these are several RNA-binding proteins, the DEAH-box helicase UAP56 and the heterodimeric nuclear export receptor NXF1:p15 (reviewed in Izaurralde, 2002; Reed and Hurt, 2002). Metazoan NXF1 (also known as TAP in humans) belongs to the conserved family of NXF proteins, which includes yeast Mex67p. p15 is conserved in metazoa but not in Saccharomyces cerevisiae; instead, the protein Mtr2p is predicted to be functionally analogous to p15 in this organism. NXF1:p15 dimers promote the translocation of mRNA cargos across the nuclear pore complex (NPC) by interacting directly with nucleoporins. Their interaction with mRNAs is thought to be mediated by adaptor proteins (Izaurralde, 2002).

The putative RNA helicase UAP56 (also known as Sub2p in yeast) was first implicated in splicing (reviewed in Linder and Stutz, 2001). Recent studies, however, provided evidence for an essential role of this protein in early steps of the mRNA export process by binding cotranscriptionally to nascent mRNAs and facilitating the recruitment of adaptor proteins (Gatfield et al., 2001; Jensen et al., 2001; Luo et al., 2001; Strasser and Hurt, 2001; Kiesler et al., 2002; Libri et al., 2002; Strasser et al., 2002; Zenklusen et al., 2002). These adaptors include members of the evolutionarily conserved family of REF proteins (Stutz et al., 2000). Yra1p (one of the S.cerevisiae members of this family) is essential for mRNA export (Strasser and Hurt, 2000; Stutz et al., 2000; Zenklusen et al., 2001), whereas Drosophila REF1 is not, indicating that other adaptors can recruit NXF1:p15 dimers to mRNAs in higher eukaryotes (Gatfield and Izaurralde, 2002).

The essential role of NXF1:p15 dimers and of UAP56 in mRNA export is well established in S.cerevisiae and Drosophila. In these organisms, inactivation or depletion of these proteins results in a strong accumulation of bulk polyadenylated RNA [poly(A)+ RNA] within the nucleoplasm, suggesting that export of a large proportion of mRNAs is affected (Segref et al., 1997; Gatfield et al., 2001; Herold et al., 2001; Jensen et al., 2001; Strasser and Hurt, 2001; Wiegand et al., 2002). Fluorescent in situ hybridizations (FISH) using probes to detect specific mRNAs have led to the identification of several mRNAs that depend on these three proteins for export, including mRNAs encoding heat shock proteins (Hurt et al., 2000; Vainberg et al., 2000; Herold et al., 2001; Jensen et al., 2001; Strasser and Hurt, 2001; Wilkie et al., 2001).

Although mRNA export is becoming increasingly well understood in yeast, the mRNA export pathway in higher eukaryotes remains ill-defined. In particular, it is unclear whether NXF1, p15 and UAP56 are components of the same pathway or whether there are classes of mRNAs that require NXF1:p15, but not UAP56, and vice versa. On a genomic scale, the fraction of mRNAs whose export is mediated by NXF1:p15 dimers and UAP56 is unknown.

Another issue that remains unsolved is whether there are classes of mRNAs that reach the cytoplasm through alternative routes, e.g. by recruiting other export receptors. Recent studies have suggested that CRM1, a nuclear export receptor belonging to the importin-β (karyopherin) family, mediates export of a subset of mRNAs (Gallouzi and Steitz, 2001). Moreover, the observation that there are two NXF proteins in Caenorhabditis elegans and four in Drosophila and humans (Herold et al., 2000) has raised the possibility that different classes of mRNAs may reach the cytoplasm by recruiting different members of the NXF family.

A role for human NXF2 and NXF3 in mRNA export is suggested by the observation that both can promote export of reporter mRNAs in cultured cells (Herold et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2001). The observation that these proteins are expressed mainly in testis indicates that they may act as tissue-specific export factors (Herold et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2001). In contrast, in Drosophila embryos, NXF2 and NXF3 are expressed ubiquitously (Herold et al., 2001). However, Drosophila cells depleted of NXF2 or NXF3 do not exhibit a detectable growth or export phenotype, suggesting that their cargos can only be non-essential mRNAs in cultured cells (Herold et al., 2001).

In order to shed light on nuclear mRNA export pathways on a genome-wide scale in higher eukaryotes, we have analyzed the relative abundance of nearly one-half of the Drosophila transcriptome in the cytoplasm of Drosophila Schneider (S2) cells in which export factors have been depleted by RNA interference (RNAi). We show that the vast majority of transcripts are underrepresented in the cytoplasm of cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 as compared with control cells. Only a small number of mRNAs are apparently not affected by the depletions and a subset of mRNAs appear to be exported by NXF1:p15 dimers independently of UAP56. In contrast, no significant changes in mRNA expression profiles are observed in cells depleted of NXF2 or NXF3. Furthermore, inhibition of the CRM1-mediated export pathway by leptomycin-B (LMB) affects the expression levels of <2% of detectable mRNAs. These observations, together with the wide effect on mRNA levels in cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56, indicate that these proteins act in the same pathway and that the functioning of this pathway is required for export of the majority of transcripts in higher eukaryotes. Finally, this study also revealed a feedback loop that results in the upregulation of mRNA export factors following the inhibition of mRNA export.

Results

Depletion of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 causes widespread changes in the expression of the Drosophila transcriptome

To analyze nuclear mRNA export pathways at the genomic level, cDNA microarrays representing a total of ∼6000 different genes (see Experimental procedures in Supplementary data available at The EMBO Journal Online) were used to screen mRNA levels in total and cytoplasmic samples isolated from S2 cells depleted of UAP56, p15 or the individual NXF proteins (NXF1, 2 and 3) by RNAi. The efficiency of all depletions was confirmed by RT–PCR and, except for NXF3, by western blot analysis (Supplementary figure 1A). NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns were confirmed further by the inhibition of cell proliferation and the concomitant strong nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA (Supplementary figure 1B; Gatfield et al., 2001; Herold et al., 2001).

The relative abundance of each transcript was analyzed 4 days (NXF1, p15 and UAP56) or 5 days (NXF2 and NXF3) after transfection with dsRNA in two-color microarray hybridization experiments. As reference samples, total and cytoplasmic RNAs isolated from cells transfected in parallel with GFP dsRNA were used. To reduce potentially insignificant variations in the preparation of the RNA, three cytoplasmic and two total RNA preparations were isolated from a single knockdown experiment. These preparations were pooled with the equivalent preparations isolated from an independent knockdown, to minimize differences in knockdown efficiencies. These pools of six cytoplasmic or four total RNA preparations from two independent knockdowns are referred to as ‘cytoplasmic or total samples’. We confirmed that all cytoplasmic RNA preparations were free of nuclear contamination by testing for the absence of rp49 and hsp83 precursor mRNAs, as described in Supplementary figure 2.

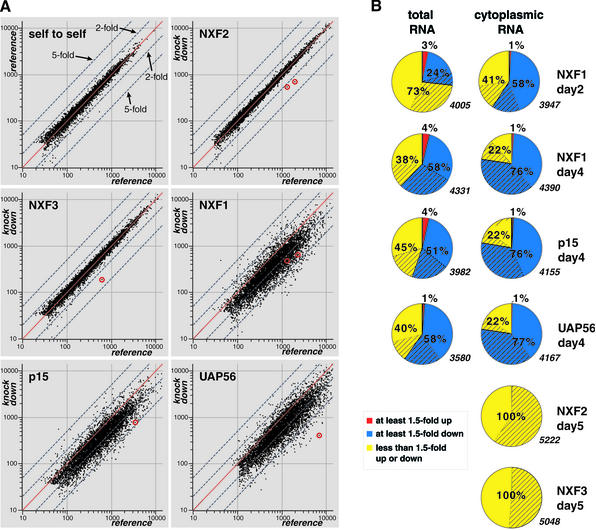

A representative measurement with one cytoplasmic sample for each export factor is shown in Figure 1A. When NXF2 or NXF3 was targeted by RNAi, the only mRNAs consistently different from the reference sample (i.e. at least 1.5-fold different in three independent measurements) were the nxf2 and nxf3 mRNAs themselves (red circles, Figure 1A). In contrast, when NXF1, p15 or UAP56 was depleted, the levels of most mRNAs changed significantly (Figure 1A). Since most mRNAs were underrepresented in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns, external spike-in RNAs were used for normalization (Supplementary data procedures).

Fig. 1. Depletion of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 results in global changes of mRNA levels. (A) Scatter plot representation of individual measurements using cytoplasmic RNA samples isolated from different knockdowns. The normalized intensity values of the experimental samples are plotted against the normalized intensity values of the reference samples. In addition to the regression line (red line: same intensity in both samples), the 2- and 5-fold lines (dashed lines) are shown. Spots representing mRNAs targeted by RNAi are marked with a red circle. NXF1 and NXF2 were each represented by two spots. (B) All detectable mRNAs were classified according to their relative expression levels. Only mRNAs that could be assigned to the same subclass in measurements performed with two independent samples for each export factor are shown. Blue, mRNAs at least 1.5-fold underrepresented; yellow, mRNAs <1.5-fold different from the reference; red, mRNAs at least 1.5-fold overrepresented. Within these classes, the dashed areas represent subgroups of mRNAs for which more stringent cut-off values were used (at least 2-fold over- or underrepresented; <1.2-fold regulated). The total number of genes considered for each pie chart (detectable mRNAs) is indicated in italics.

To compare further the effects of the NXF1, p15 and UAP56 depletions, we sorted all detectable mRNAs into three classes according to their relative expression levels (Figure 1B). These include mRNAs that were at least 1.5-fold underrepresented compared with the reference sample (blue), not significantly changed (<1.5-fold different from the reference, yellow), or at least 1.5-fold overrepresented (red). Within these classes, the dashed areas represent subgroups of mRNAs for which more stringent cut-off values were used (at least 2-fold over- or underrepresented; <1.2-fold regulated).

A particular mRNA was only considered for further analysis if it could be assigned to the same subclass in measurements performed with two independent cytoplasmic or total samples for each export factor. About three-quarters (76–77%) of detectable mRNAs were underrepresented (at least 1.5-fold down) in the cytoplasm of cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56; 22% were <1.5-fold different from the control and only 1% were overrepresented (at least 1.5-fold up; Figure 1B). When total RNA samples isolated on day 4 from NXF1-, p15- or UAP56-depleted cells were analyzed, about one-half (51–58%) of detectable mRNAs were underrepresented compared with the reference sample, 38–45% were not significantly changed and 1–4% were overrepresented (Figure 1B).

As the accumulation of mRNAs in the nucleus should result in their cytoplasmic depletion, a widespread reduction of cytoplasmic mRNA levels upon depletion of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 was expected. In contrast, the overall reduction in total mRNA levels was not expected a priori. However, a similar reduction in total mRNA levels has been observed in yeast cells in which mRNA export is inhibited (see Discussion). Experiments described below indicate that this overall decrease in mRNA levels is a consequence of the mRNA export block.

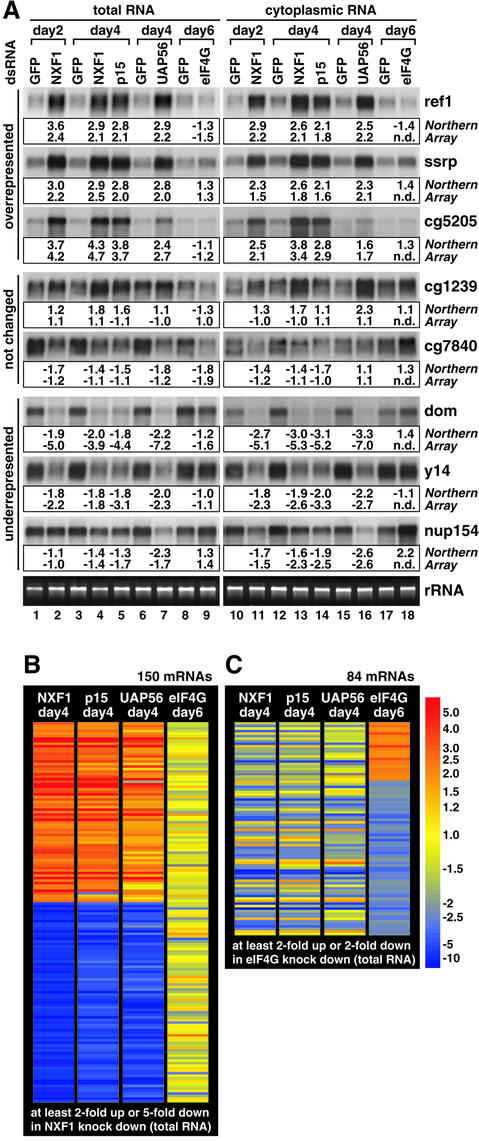

The overall reduction in mRNA levels is a specific effect of the nuclear export block

To validate the microarray data, we selected representative mRNAs of each class and determined their relative levels by northern blot analysis (Figure 2A). The changes observed in the microarray experiment always showed the same positive or negative trend as the changes measured by northern blotting (Figure 2A), both in total and cytoplasmic samples. mRNAs that were not significantly different from control samples in the array experiment were only slightly different from control samples when measured by northern blotting. We also confirmed the positive or negative trend of several other mRNAs by RT–PCR (data not shown).

Fig. 2. The general reduction in mRNA expression levels is a specific effect of the mRNA export inhibition. (A) A 10 µg aliquot of total or cytoplasmic RNA was analyzed by northern blot using probes to detect different selected mRNAs as indicated. Knockdown samples should be compared with the corresponding control samples isolated from cells treated in parallel with GFP dsRNA. RNA samples were isolated 2, 4 or 6 days after transfection of dsRNAs, as indicated above the lanes. The lower panel shows the corresponding rRNA stained with ethidium bromide. The signals from the northern blot were quantified using a PhosphorImager and compared with the value measured by the microarray analysis of the same RNA sample. Values are given as fold changes (positive values: overrepresented; negative values: underrepresented compared with the reference). n.d., not determined. (B and C) The expression levels of mRNAs, which were at least 2-fold up- or at least 5-fold downregulated in total samples of NXF1-depleted cells, were analyzed in p15, UAP56 and eIF4G knockdowns (B). The expression levels of mRNAs, which were at least 2-fold over- or underrepresented in total samples of eIF4G-depleted cells, were analyzed in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns (C). RNA samples were isolated 4 or 6 days after transfection of dsRNAs, as indicated above the panels. Each mRNA is colored according to its relative expression level. The number of mRNAs displayed is indicated above the panels. The color bar indicates fold changes.

To ensure that the global changes of mRNA expression levels observed in NXF1-, p15- or UAP56-depleted cells are caused by the inhibition of mRNA export, rather than being a non-specific response to the depletion of essential proteins, we analyzed total RNA samples isolated 6 days after depletion of the essential translation factor eIF4G. We have shown before that depletion of eIF4G from S2 cells strongly impairs cell proliferation, but does not lead to the nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA (Herold et al., 2001).

To highlight differences in mRNA expression patterns between cells depleted of NXF1, p15, UAP56 or eIF4G, we selected mRNAs that were highly regulated (at least 2-fold up or at least 5-fold down) in the NXF1 knockdown and investigated their expression levels in the other three knockdowns (Figure 2B). While these mRNAs exhibited strikingly similar expression profiles in p15 and UAP56 samples, in most cases their levels remained unchanged in cells depleted of eIF4G (79%, <1.5-fold regulated). Northern blot analysis confirmed that mRNAs showing higher or lower levels in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns were usually not strongly affected by depletion of eIF4G (Figures 2A and 5B). We conclude that mRNAs over- or underrepresented after depletion of NXF1, p15 and UAP56 do not represent mRNAs that are generally regulated in response to the inhibition of translation or cell proliferation.

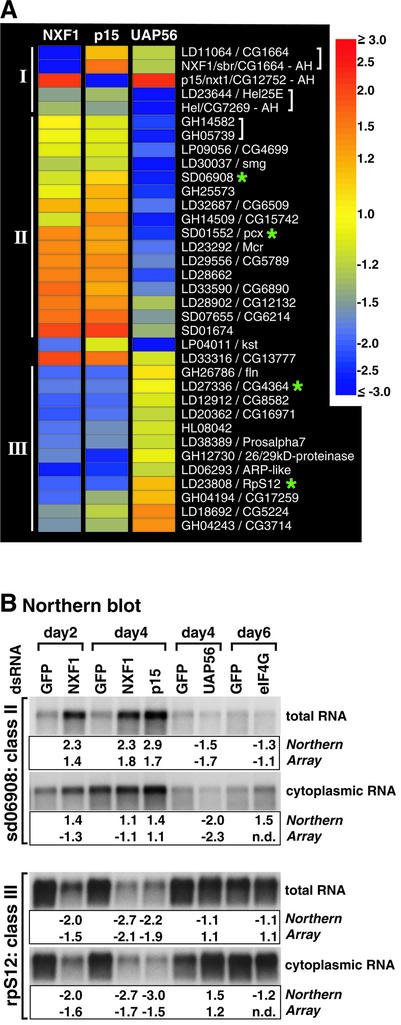

Fig. 5. A class of mRNAs that are differentially affected in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns. (A) List of differentially expressed mRNAs in the cytoplasm of cells depleted of NXF1, p15 and UAP56. The criteria applied to select these mRNAs can be found in Supplementary table III. The four mRNAs tested by northern blot analysis are marked with a green star. Each mRNA is colored according to its relative expression level. Note the different scale of the color bar in this figure. Spots representing the same mRNA are marked with brackets. (B) Northern blot membranes shown in Figure 2A were probed for two candidate mRNAs present in the list. The signals obtained with SD06908 and RpS12 probes were quantified and compared with the values measured in the microarray experiment using the same pool of RNAs. Symbols are as in Figure 2A.

Similarly, genes that are highly regulated in eIF4G-depleted cells (in this case, at least 2-fold up or down) were either unaffected in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns or were regulated but did not always exhibit the same trend (Figure 2C). These results indicate that the mRNA expression profiles displayed by NXF1-, p15- or UAP56-depleted cells represent a specific signature of these knockdowns.

A block of mRNA nuclear export causes an overall reduction in total mRNA levels

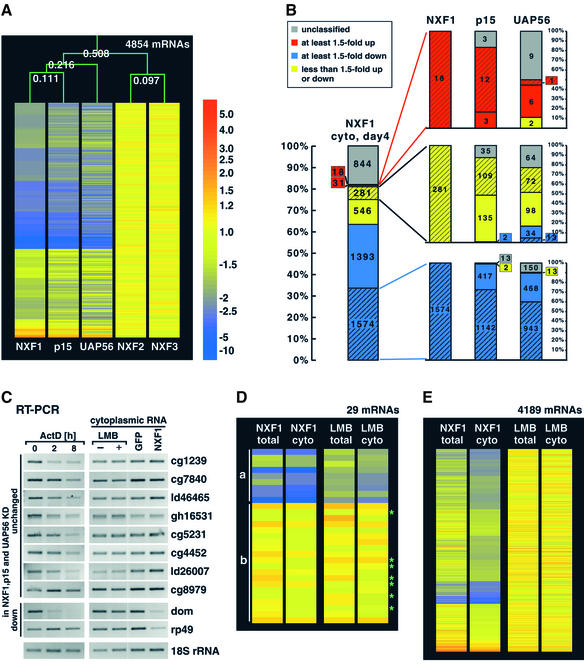

To obtain support for the hypothesis that the decreased mRNA levels in the total samples are an effect of the mRNA export block, we analyzed RNA samples isolated 2 days after transfection of cells with NXF1 dsRNA. At this time point, ∼60% of all detectable mRNAs were underrepresented in the cytoplasm, but <25% were in the total samples (Figure 1B, day 2 and Figure 4E). Thus, the cytoplasmic depletion of mRNAs precedes the overall reduction in total mRNA levels, suggesting that the latter may be a secondary consequence of the mRNA export inhibition.

Fig. 4. Cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 exhibit similar mRNA expression profiles. (A) Comparison of the relative expression levels of all detectable mRNAs (4854) in cytoplasmic samples (day 4 for NXF1, p15 and UAP56; day 5 for NXF2 and NXF3). The mRNAs are colored according to their expression levels. For each mRNA, the average levels from all measurements for each knockdown are shown. The experiment tree above was calculated using the distance option in the GeneSpring software (Euclidian distance). (B) The cytoplasmic levels of mRNAs which were at least 2-fold overrepresented, at least 2-fold underrepresented and <1.2-fold changed in cytoplasmic samples of NXF1-depleted cells (red, blue and yellow dashed areas) were analyzed in cytoplasmic samples of p15 and UAP56 knockdowns (day 4). The number of mRNAs in each class is indicated. Red, blue and yellow dashed and undashed areas are as described in Figure 1B. The ‘unclassified’ mRNAs (gray) represent transcripts that were assigned to two different subclasses in two independent microarray measurements. (C) RT–PCRs were performed with cytoplasmic RNA samples isolated from S2 cells treated with LMB for 12 h and cells depleted of NXF1 (day 4). The levels in the experimental sample should be compared with the corresponding control sample (without LMB treatment or GFP, respectively). The levels of the different mRNAs were analyzed in parallel in total RNA samples isolated from S2 cells treated with actinomycin D (5 µg/ml) for 0, 2 or 8 h. (D) The expression levels of the 20 mRNAs that were unchanged in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns (group b) and of the nine mRNAs that were at least 1.5-fold underrepresented in the cytoplasmic samples of LMB-treated cells (group a) were analyzed in total and cytoplasmic samples of NXF1 knockdowns (day 2) and of LMB-treated cells. The seven short-lived mRNAs shown in (C) are labeled with a green star. (E) Comparison of the relative expression levels of all detectable mRNAs (4189) in cytoplasmic and total samples isolated from cells depleted of NXF1 (day 2) or treated with LMB (12 h). In (D) and (E), mRNAs are colored according to their average expression levels in measurements performed with two independent samples. The color bar is shown in (A).

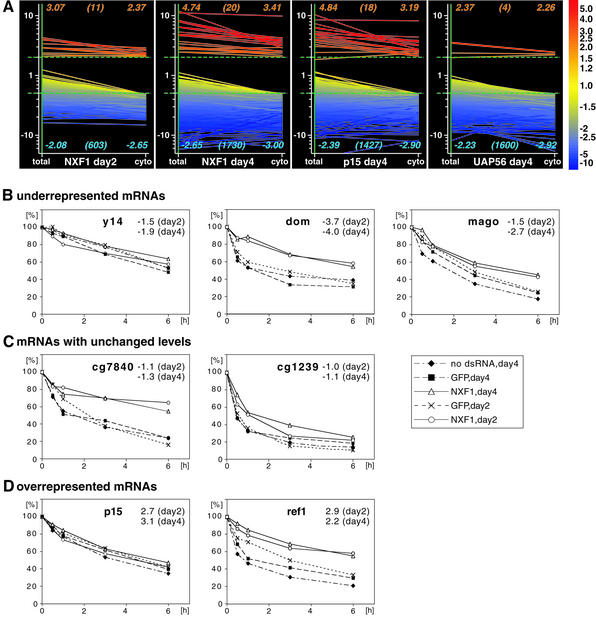

In cells in which mRNA export is inhibited, we would expect the reduction in mRNA levels to be more obvious in the cytoplasmic rather than in the total samples. To test whether this was the case, we selected mRNAs that were at least 2-fold underrepresented in the cytoplasmic samples of NXF1-, p15- or UAP56-depleted cells, and analyzed their relative levels in total RNA samples. In the three knockdowns, the average relative mRNA levels were lower in the cytoplasmic samples (Figure 3A, blue numbers at the bottom of each graph). Moreover, the difference between total and cytoplasmic average expression levels was greater on day 2 than on day 4. Finally, when the average relative levels of mRNAs at least 2-fold overrepresented in the cytoplasmic samples of NXF1-, p15- or UAP56-depleted cells were analyzed, we observed higher average levels in the total samples, providing additional evidence for an export block.

Fig. 3. The general reduction in mRNA expression levels is not due to increased mRNA turnover rates. (A) mRNAs that are at least 2-fold overrepresented (red) or underrepresented (blue) in the cytoplasmic samples of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 knockdowns were selected and their levels in total samples were analyzed. Each mRNA is represented as a line colored according to its relative expression level in the total RNA sample. The number of displayed mRNAs in the respective classes is indicated in brackets. The numbers in the top and bottom corners of each graph are the average relative expression levels of the respective classes. (B–D) S2 cells were treated with NXF1 or GFP dsRNAs. Two or 4 days after transfection, treated or untreated cells were incubated with actinomycin D (5 µg/ml) and total RNA was isolated 0.5, 1, 3 and 6 h after the addition of the drug. The levels of selected mRNAs were determined by northern or slot blot analysis and normalized to rp49 mRNA (whose level does not change during the timescale of the experiment). Values are expressed as a percentage of the levels at time 0 (set to 100%) and plotted as a function of time. The relative expression levels of the respective mRNAs in the NXF1 knockdowns (total samples) measured by microarray analysis are given in the top right corner of each graph.

The reduction in cytoplasmic and total mRNA levels is not a direct consequence of higher mRNA turnover rates

The experiments described above suggest that the overall decrease in abundance of most mRNAs observed in cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 is caused by export inhibition. However, these experiments do not reveal the mechanism by which this decreased expression is achieved. One possibility is that mRNAs accumulating within the nucleus have a higher turnover rate. To test this, we measured the half-lives of four representative mRNAs selected from those that were underrepresented in total and cytoplasmic samples of cells depleted of NXF1 (Figure 3B; data not shown). None of these mRNAs had a higher turnover rate in NXF1 knockdowns compared with control cells, regardless of whether samples were collected 2 or 4 days after transfecting NXF1 dsRNA (Figure 3B, solid versus dashed lines). On the contrary, some of the selected mRNAs had an increased stability. For instance, the half-life of dom mRNA is ∼2–3 h in wild-type cells and >6 h in NXF1-depleted cells (Figure 3B).

We also measured the half-lives of seven mRNAs selected from those whose expression in cytoplasmic samples of NXF1-depleted cells was unchanged (two mRNAs, Figure 3C) or was increased (five mRNAs, Figure 3D; data not shown). Again, the half-lives of these mRNAs remained unchanged or increased in NXF1-depleted cells (Figure 3C and D). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that some mRNA species might have a reduced stability in NXF1 knockdowns, together these results favor a model in which the overall decrease in mRNA levels is not caused by post-transcriptional mRNA decay.

Depletion of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 leads to strikingly similar mRNA expression profiles

As shown in Figure 2B, mRNAs that are highly over- or underrepresented in total samples isolated from NXF1-depleted cells are coherently regulated in p15 or UAP56 knockdowns. This is also observed when all detectable mRNAs in the cytoplasmic samples of cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 are compared (Figure 4A). The mRNA expression pattern caused by the depletion of NXF1 is more similar to that of p15 depletion than to that of the UAP56 knockdown (Figure 4A). Indeed, the only mRNAs that were significantly different in NXF1 and p15 knockdowns were those targeted by RNAi themselves (Figure 5A; Supplementary table III).

To investigate further the uniformity of the cellular response to the depletion of NXF1, p15 or UAP56, we selected mRNAs belonging to specific classes in cytoplasmic samples of the NXF1 knockdown (at least 2-fold overrepresented, at least 2-fold underrepresented or <1.2-fold changed; red, blue and yellow dashed areas, respectively) and analyzed their levels in p15 or UAP56 knockdowns (Figure 4B). Of the mRNAs that were at least 2-fold underrepresented in the NXF1 knockdown, 99 or 90% were at least 1.5-fold underrepresented in p15 or UAP56 knockdowns, respectively (Figure 4B). Overall, mRNAs that were not changed, over- or underrepresented in one experiment usually showed the same trend in the other two experiments, with smaller deviations between the NXF1 and p15 data than between NXF1 and UAP56 or p15 and UAP56 knockdown experiments. This also holds true when total RNA samples are compared (data not shown). The striking similarity of the patterns of mRNA expression in NXF1 (or p15) and UAP56 knockdowns strongly suggests that these proteins act in the same pathway.

Export of a subset of transcripts is apparently unaffected by NXF1, p15 or UAP56 depletion

Although most mRNAs show decreased expression levels in NXF1-, p15- or UAP56- depleted cells, the cytoplasmic levels of 23 mRNAs were unchanged after depletion of any one of these three export factors (<1.2-fold regulated in all measurements). For 20 of these mRNAs, the total levels were also not significantly affected (Supplementary table I). These mRNAs were not depleted from the cytoplasmic fraction despite the general nuclear export block, suggesting that they could have been exported independently of NXF1, p15 and UAP56 or could recruit these proteins very efficiently, so that the residual levels of these proteins in depleted cells were not limiting for their export. Alternatively, these mRNAs could have extremely low turnover rates.

To distinguish between these possibilities, the stability of two mRNAs belonging to this class was determined. The stability of cg1239 mRNA was only slightly changed, while the stability of cg7840 mRNA was increased in cells depleted of NXF1 (Figure 3C). Nonetheless, the half-lives of both mRNA species were not long enough (e.g. cg1239 half-life <2 h) to account for unchanged cytoplasmic levels in cells in which mRNA export has been efficiently blocked for at least 2 days [as judged by oligo(dT) in situ hybridization; Supplementary figure 1B]. We therefore conclude that neither transcription nor export of these mRNAs is significantly inhibited. These mRNAs thus represent transcripts that can either recruit NXF1, p15 and UAP56 more efficiently than bulk mRNA or exit the nucleus via an alternative export pathway. Because a role for NXF2 or NXF3 in this putative alternative pathway could be ruled out, it was of interest to investigate whether these mRNAs were exported by CRM1.

CRM1 is not a major mRNA export receptor in Drosophila

The CRM1 export pathway was inhibited by LMB, which prevents CRM1 binding to RanGTP and the export cargo (reviewed in Görlich and Kutay, 1999). The efficiency of the LMB treatment was confirmed by analyzing the subcellular localization of two endogenous proteins, PYM and Extradenticle, which are both exported by CRM1 (Supplementary figure 3). Because CRM1 has been implicated in multiple export processes (i.e. export of various proteins, U snRNAs and ribosomal subunits), prolonged exposure to LMB leads to pleiotropic effects including the accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA within the nucleus of yeast and human cells. To avoid these indirect effects, we isolated total and cytoplasmic RNA samples from cells treated with LMB for 12 h. This time was chosen from the observation that the half-life of ∼70% of Drosophila mRNAs is between 0.5 and 7 h (our unpublished observations; Lengyel et al., 1977). Thus, we reasoned that a 12 h LMB treatment should be long enough to detect changes in expression levels of at least 70% of transcripts, but short enough to avoid indirect effects. Consistently, no nuclear accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA was observed in S2 cells treated with LMB for 12 h (Supplementary figure 3).

Next, we randomly selected 10 mRNAs among the 20 transcripts whose levels remained unchanged in cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 and analyzed their expression levels by RT–PCR in total and cytoplasmic samples of cells treated with LMB (Figure 4C; data not shown). A rough estimation of the half-life of these transcripts was obtained by analyzing their levels in total RNA samples isolated from cells treated with actinomycin D for 2 and 8 h (Figure 4C). In agreement with our prediction, seven out of 10 transcripts were short-lived mRNAs (Figure 4C; data not shown). Nonetheless, the levels of these mRNAs remained unchanged in total and cytoplasmic samples isolated from LMB-treated cells (Figure 4C; Supplementary table I). By RT–PCR we could detect a reduction in dom and rp49 mRNA levels in cytoplasmic samples isolated from NXF1-depleted cells, as expected (Figure 4C).

To confirm the RT–PCR data and monitor the expression levels of all mRNAs of this class, we performed a microarray analysis with total and cytoplasmic samples isolated from two independent LMB treatments. None of the 20 transcripts whose levels remained unchanged in cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 was affected by the LMB treatment (Figure 4D, group b; Supplementary table I). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the long-lived mRNAs of this class (half-life >2 h) reach the cytoplasm by recruiting CRM1, at least seven out of 20 (and probably more) of these transcripts are not exported by CRM1.

The possibility that CRM1 mediates the export of a large proportion of transcripts could also be ruled out, as both in total and cytoplasmic RNA samples isolated from LMB-treated cells 98–99% of detectable mRNAs were unaffected (<1.5-fold different from the control sample), 1% were overrepresented (at least 1.5-fold up) and <0.5% were underrepresented (at least 1.5-fold down) (Figure 4E). A list of mRNAs regulated in LMB-treated cells is provided in Supplementary table II.

With the caveat that the kinetics and efficiency of the export inhibition by LMB and by depleting export factors by RNAi are not comparable, the RNA expression profiles observed in cytoplasmic or total RNA samples isolated from LMB-treated cells were in sharp contrast to the global changes observed in samples isolated from NXF1-depleted cells (day 2, Figure 4E). Note that a 2 day treatment with NXF1 dsRNA corresponds to an export block of <20 h, as judged by oligo(dT) in situ hybridization (not shown).

Finally, the small subset of mRNAs that were underrepresented in the cytoplasm of LMB-treated cells, and thus potentially exported by CRM1, were also underrepresented in the cytoplasm of NXF1-depleted cells (day 2), suggesting that these mRNAs may not represent genuine CRM1 export cargos (Figure 4D, group a; Supplementary table II). In summary, our observations argue against a role for CRM1 in the export of a large fraction of mRNAs.

A set of mRNAs is differently affected in NXF1, p15 or UAP56 knockdowns

Despite the similarities of the mRNA expression profiles in cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56, 32 mRNAs exhibiting differential expression in the three different knockdowns were detected (Figure 5; Supplementary table III). Most mRNAs could be sorted into three classes: I, mRNAs targeted by RNAi (3/32); II, mRNAs underrepresented in the UAP56 knockdown, but not affected or overrepresented in the NXF1 and p15 knockdowns (15/32); III, mRNAs underrepresented in NXF1 and p15 knockdowns, but not affected or overrepresented in the UAP56 knockdown (12/32).

The microarray data were validated by RT–PCR for all mRNAs of class I (Figure 6B), and by northern blotting for four selected mRNAs belonging to classes II or III (Figure 5B; data not shown). One of the tested mRNAs of class III encodes the ribosomal protein S12. This and the additional class III mRNAs, which exhibit reduced expression levels in NXF1 and p15 knockdowns, but not in the UAP56 knockdown, are likely to be exported independently of UAP56 function. Despite the similarities in their expression pattern, however, the predicted function of the proteins encoded by class II or III transcripts is heterogeneous. The similar behavior of these mRNAs may be related to common sequence or structural elements present in the transcript.

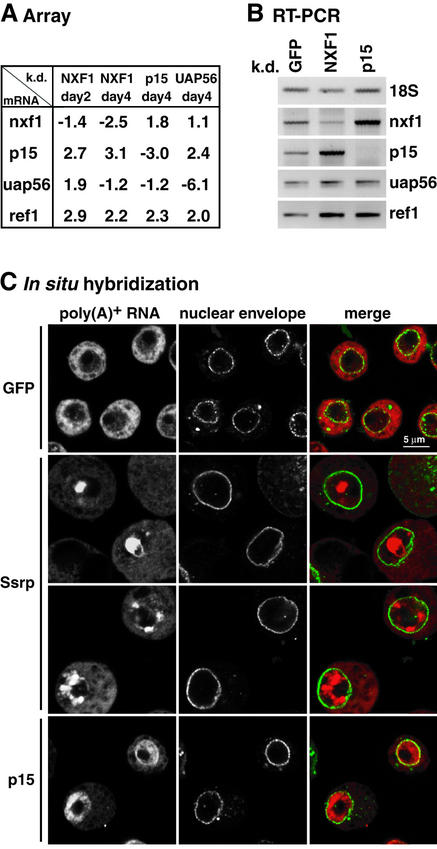

Fig. 6. A block of nuclear mRNA export results in the upregulation of mRNAs encoding export factors. (A) Average relative expression values for nxf1, p15, uap56 and ref1 mRNAs determined by microarray analysis of total RNA samples isolated from NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns. The values are fold changes averaged from two different measurements for each knockdown and also averaged if several spots represent one mRNA species. (B) The values shown in (A) (day 4) were confirmed by RT–PCR with primers specific for 18S rRNA and nxf1, p15, uap56 and ref1 mRNAs. (C) S2 cells were transfected with dsRNA corresponding to GFP (control), p15 or Ssrp. Cells were fixed 10 (GFP, Ssrp) or 5 (p15) days after transfection. Poly(A)+ RNA was detected by FISH with an oligo(dT) probe (red). The nuclear envelope was stained with Alexa488-WGA (green). Two examples of Ssrp- depleted cells collected 10 days after addition of Ssrp dsRNA are shown. At this time point, >80% of cells show a strong accumulation of poly(A)+ RNA in nuclear dots, but the number and size of these dots are variable, as illustrated in the two images.

A block of mRNA nuclear export causes the upregulation of genes involved in this process

Among the mRNAs differentially expressed in NXF1, p15 or UAP56 knockdowns were the mRNAs targeted by RNAi. Surprisingly, p15 mRNA was not only underrepresented in the corresponding p15 knockdown, but was overrepresented in NXF1 and UAP56 knockdowns (Figures 5A and 6A). Similarly, nxf1 mRNA was overrepresented in the p15 knockdown (Figures 5A and 6A). UAP56 mRNA was overrepresented in samples isolated from NXF1-depleted cells on day 2. This upregulation was no longer observed on day 4 (Figure 6A). Remarkably, the mRNA encoding REF1 was also overrepresented in cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 (Figure 6A; Supplementary table IV). These data were verified by RT–PCR (Figure 6B). Notably, the increased levels of these mRNAs were detected in both total and cytoplasmic RNA samples, but did not usually result in a strong increase of the protein levels.

As the turnover rate of p15 mRNA was not significantly altered in NXF1 knockdowns (Figure 3D), the increased steady-state levels of this mRNA are likely to be caused by a higher rate of transcription. In contrast, ref1 mRNA was stabilized in cells depleted of NXF1 (Figure 3D). We conclude that transcriptional upregulation and mRNA stabilization both contribute to the increased levels of transcripts encoding nuclear export factors. These results revealed the existence of a feedback loop by which a block to nuclear export leads to increased levels of mRNAs encoding transport factors.

Prompted by this observation, we investigated whether depletion of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 results in the upregulation of additional, unknown components of the nuclear mRNA export pathway. To identify potential candidates we generated a list of mRNAs that were at least 2-fold overrepresented in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns (Supplementary table IV). A closer inspection of these genes indicated that some encode proteins that are unlikely to be implicated in export, but in most cases the gene products were poorly characterized (Supplementary table IV).

From this list we selected four candidate mRNAs encoding the following proteins: CG7163 (zinc-finger domain protein), CG15612 (protein belonging to the rhoGEF family), Ssrp (single-stranded RNA and DNA-binding protein) and CG5205 (RNA helicase, component of U5 snRNP). Northern blot analysis confirmed that ssrp and cg5205 transcripts were indeed overrepresented in NXF1, p15 and UAP56 knockdowns (Figure 2A).

A possible role in export for these selected candidates was investigated by silencing their expression by RNAi and analyzing the distribution of bulk mRNA by oligo(dT) in situ hybridization. We monitored cell proliferation in parallel. In contrast to cells depleted of CG7163, CG15612 or CG5205, which showed no obvious growth or export phenotype, cells depleted of Ssrp proliferated more slowly than control cells (data not shown). This reduction of proliferation was significant, but was not as dramatic as that observed when NXF1 is depleted (data not shown). Moreover, ∼6 days after transfection of Ssrp dsRNA, the size of cells increased compared with control cells (Figure 6C).

Remarkably, starting from day 8, cells depleted of Ssrp displayed a highly abnormal distribution of poly(A)+ RNA (Figure 6C). While in NXF1, p15 or UAP56 knockdowns poly(A)+ RNA accumulated evenly within the nuclear compartment (Figure 6C; Supplementary figure 1B), in Ssrp-depleted cells poly(A)+ RNAs accumulated in nuclear foci (Figure 6C). These structures did not coincide with the nucleolus, and their staining was strongly reduced after RNase A treatment, indicating that they consisted of RNA (data not shown). These results suggest a role for Ssrp in the nuclear export of polyadenylated RNAs.

Discussion

NXF1, p15 and UAP56 define a single pathway in Drosophila

Although Drosophila NXF1, p15 and UAP56 have been shown to be essential for nuclear export of bulk mRNA (Gatfield et al., 2001; Herold et al., 2001; Wiegand et al., 2002), prior to this study it was unclear whether the export of all mRNAs depends on these three proteins and whether mRNAs will be found that require NXF1 and p15 function, but not UAP56 function, or vice versa. In this study we showed that depletion of any one of these proteins resulted in strikingly similar changes in mRNA expression profiles, indicating that these three proteins act in the same pathway. Consequently, NXF1:p15 heterodimers can only be recruited to most mRNAs when UAP56 is present.

An exception to this rule is provided by a small group of mRNAs whose levels did not change in UAP56-depleted cells, but were decreased in the cytoplasm of cells depleted of NXF1 or p15 (Supplementary table III, class III). These mRNAs may recruit NXF1:p15 heterodimers via a UAP56-independent mechanism. Further studies will be required to determine the specific features of this particular class of mRNAs.

Cotranscriptional mRNA decay may account for decreased mRNA levels after export inhibition

We showed that the overall reduction of mRNA levels in total samples isolated from cells depleted of NXF1, p15 or UAP56 is a specific signature of the knockdowns, but the mechanism by which this decrease is achieved remains to be established. A block to mRNA export could lead to either a decreased stability of mRNAs accumulating within the nucleus, a reduction of the transcriptional activity in depleted cells, or a cotranscriptional degradation of newly synthesized mRNAs.

Changes in transcription levels are very likely to contribute to the observed overall changes in gene expression. However, several lines of evidence indicate that transcription is not generally inhibited in depleted cells. First, in these cells the total levels of 10–15% of tested mRNAs remain unchanged (<1.2-fold), and 1–4% of mRNAs are upregulated (at least 1.5-fold) (Figure 1B). Since mRNA export has been inhibited efficiently on day 2, unchanged or increased mRNA levels on day 4 cannot be attributed solely to a higher stability of the respective transcripts, but are also indicative of ongoing transcription. Secondly, heat shock mRNA synthesis can be induced in depleted cells to similar levels as in wild-type cells (Gatfield et al., 2001; Herold et al., 2001), indicating that the transcription machinery is functional in these cells.

None of the underrepresented mRNAs tested in this study displayed a higher turnover rate in cells depleted of NXF1, suggesting that, if degradation occurs, it is not post-transcriptional. A reduction in total mRNA levels has also been observed in yeast strains in which mRNA export has been inhibited as a consequence of mutations in genes encoding export factors, including sub2 (Libri et al., 2002; Zenklusen et al., 2002). This reduction is overcome in a genetic background in which individual components of the exosome are inactivated (Libri et al., 2002; Zenklusen et al., 2002), indicating that following an export block, mRNAs are degraded by the exosome. Interestingly, it has recently been reported that components of the exosome associate with elongating RNA polymerase II in Drosophila (Andrulis et al., 2002). It might therefore be possible that the overall reduction in mRNA levels observed in our study is due to cotranscriptional degradation. In the future, it would be of great interest to determine whether the exosome is responsible for the reduction of mRNA levels observed in Drosophila cells depleted of mRNA export factors.

Alternative export pathways

Prior to this study, the fraction of mRNAs that might be exported by alternative export pathways, e.g. by recruiting CRM1 or other members of the NXF family, was unknown. Although we have identified 20 transcripts whose export was apparently not affected by the depletion of NXF1, p15 or UAP56, our data indicate that at least seven (and probably more) of these mRNAs do not reach the cytoplasm by recruiting CRM1, and none of them is exported by NXF2 or NXF3. Notably, these mRNAs do not encode proteins with related biochemical functions, but may share common sequence or structural elements, enabling them either to recruit NXF1, p15 and UAP56 more efficiently or to have access to other unidentified export receptors.

Despite monitoring the relative cytoplasmic expression levels of ∼6000 different mRNAs, we have not been able to identify any potential mRNA export substrate for NXF2 or NXF3. It should be noted that NXF2 or NXF3 is unlikely to have redundant functions in S2 cells as these proteins share <20% identity, exhibit a different subcellular localization, and no phenotype is observed in cells in which both proteins are simultaneously depleted (Herold et al., 2001; our unpublished data). Moreover, <0.5% of detectable transcripts (those underrepresented in LMB-treated cells) represent potential CRM1 cargos. The possibilities that additional substrates were not represented on the array, or that some CRM1 substrates escape detection because they have long half-lives (>12 h), cannot be ruled out. Also, it is possible that CRM1, NXF2 or NXF3 plays a role in the export of specific transcripts expressed in different developmental stages or tissues, but not in S2 cells. Despite these caveats, our data suggest that only a small fraction of mRNAs is likely to reach the cytoplasm by an alternative route.

Our conclusions are in sharp contrast with those of a recent manuscript in which transcripts associating with export factors were identified on a genomic scale by co-immunoprecipitation from yeast cell lysates (Hieronymus and Silver, 2003). Contrary to expectation <20% of the yeast transcriptome was shown to associate with Mex67p, suggesting that a large fraction of mRNAs may reach the cytoplasm by alternative routes. Currently, it is unclear whether the discrepancy between our study and that of Hieronymus and Silver (2003) reflects differences between the two experimental approaches, or between yeast and higher eukaryotes.

A feedback mechanism triggered by a block of nuclear export

This study led to the discovery of a feedback loop by which a block of nuclear export triggers the upregulation of genes encoding nuclear export factors. This upregulation is achieved both by transcriptional activation and stabilization of the respective mRNAs. The existence of this feedback mechanism prompted us to investigate whether some of the upregulated genes encode unknown transport factors. Remarkably, silencing the expression of one (Ssrp) out of four selected genes led to an accumulation of mRNAs in nuclear foci.

The role of Ssrp in vivo is not well understood. The human homolog of Ssrp is a component of the FACT complex implicated in transcription elongation in vitro (Orphanides et al., 1999). Drosophila Ssrp binds single-stranded DNA and RNA in vitro and has been shown to interact with CHD1, a chromatin remodeling ATPase recently implicated in transcriptional termination by RNA polymerase II (Kelley et al., 1999; Alén et al., 2002). Data presented in this study suggest that, in addition to a putative role in transcription, Ssrp is also implicated in export of poly(A)+ RNA to the cytoplasm, although the precise mechanism by which Ssrp plays a role in this process remains to be investigated.

Although further studies are required to determine whether other upregulated mRNAs encode proteins involved in export, it is interesting to note that four of these mRNAs encode proteins of the ABC class of ATPases. A role in mRNA export for a non-membrane member of this protein family has been reported recently in Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Kozak et al., 2002).

Materials and methods

Cell culture, RNAi and FISH

RNAi and FISH were performed as described before (Herold et al., 2001). Most dsRNAs used in this study have been described (Gatfield et al., 2001; Herold et al., 2001). Ssrp dsRNA corresponds to nucleotides 1–694 of Ssrp cDNA.

RNA isolation, RT–PCR and northern blot analysis

Cytoplasmic RNA was isolated by hypotonic lysis as described in Supplementary experimental procedures. Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen). The concentration of all RNA samples was determined by measuring the optical density at 260 nm. The quality and the concentration of all RNA preparations were checked further by visualizing the rRNA in denaturing agarose gels and by RT–PCR as described in Supplementary figure 2.

Northern blotting and RT–PCR were performed as described by Herold et al. (2001) except that random hexamers were used to prime the reverse transcription reaction. Probes recognizing ref1, y14, mago and p15 mRNAs correspond to the complete cDNA of the respective gene. Partial cDNA fragments corresponding to 18S rRNA, Ssrp, RpS12, SD06908, CG1239, CG7840, CG5205 and Dom (CG4029, jumu) were amplified by PCR from a random-primed S2 cDNA library. The identity of the amplified product was confirmed by sequencing. These products served as templates to generate radiolabeled probes. All oligonucleotide sequences are available upon request.

Construction of Drosophila microarrays, microarray hybridizations, data acquisition and analysis

The microarray data are available in the ArrayExpress database at EBI under accession Nos A-MEXP-1 and E-MEXP-4. Construction of the microarrays, target-preparation, hybridization conditions, data acquisition and analysis are described in Supplementary data.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to G.K.Christophides, M.Muckenthaler, B.Minana, and C.Schwager for advice and reagents. We thank members of W.Ansorge and M.Hentze groups and the Gene Core Facility at EMBL for helpful discussions, and E.Furlong and D.Thomas for critical comments on the manuscript. L.T. was supported by the Programa Gulbenkian de Doutoramento em Biologia e Medicina (Portugal) and a fellowship from the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Portugal).

References

- Alén C., Kent,N.A., Jones,H.S., O’Sullivan,J., Aranda,A. and Proudfoot,N.J. (2002) A role for chromatin remodeling in transcriptional termination by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell, 10, 1441–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis E.D., Werner,J., Nazarian,A., Erdjument-Bromage,H., Tempst,P. and Lis,J.T. (2002) The RNA processing exosome is linked to elongating RNA polymerase II in Drosophila. Nature, 420, 837–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallouzi I.E. and Steitz,J.A. (2001) Delineation of mRNA export pathways by the use of cell-permeable peptides. Science, 294, 1895–1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D. and Izaurralde,E. (2002) REF1/Aly and the additional exon junction complex proteins are dispensable for nuclear export. J. Cell Biol., 159, 579–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatfield D., Le Hir,H., Schmitt,C., Braun,I.C., Kocher,T., Wilm,M. and Izaurralde,E. (2001) The DExH/D box protein HEL/UAP56 is essential for mRNA nuclear export in Drosophila. Curr. Biol., 11, 1716–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Görlich D. and Kutay,U. (1999) Transport between the cell nucleus and the cytoplasm. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol., 15, 607–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold A., Suyama,M., Rodrigues,J.P., Braun,I.C., Kutay,U., Carmo-Fonseca,M., Bork,P. and Izaurralde,E. (2000) TAP (NXF1) belongs to a multigene family of putative RNA export factors with a conserved modular architecture. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 8996–9008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold A., Klymenko,T. and Izaurralde,E. (2001) NXF1/p15 heterodimers are essential for mRNA nuclear export in Drosophila. RNA, 7, 1768–1780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hieronymus H. and Silver,P.A. (2003) Genome-wide analysis of RNA–protein interactions illustrates specificity of the mRNA export machinery. Nat. Genet., 33, 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt E., Strasser,K., Segref,A., Bailer,S., Schlaich,N., Presutti,C., Tollervey,D. and Jansen,R. (2000) Mex67p mediates nuclear export of a variety of RNA polymerase II transcripts. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 8361–8368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde E. (2002) A novel family of nuclear transport receptors mediates the export of messenger RNA to the cytoplasm. Eur. J. Cell Biol., 81, 577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen T.H., Boulay,J., Rosbash,M. and Libri,D. (2001) The DECD box putative ATPase Sub2p is an early mRNA export factor. Curr. Biol., 11, 1711–1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley D.E., Stokes,D.G. and Perry,R.P. (1999) CHD1 interacts with SSRP1 and depends on both its chromodomain and its ATPase/helicase-like domain for proper association with chromatin. Chromosoma, 108, 10–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiesler E., Miralles,F. and Visa,N. (2002) HEL/UAP56 binds cotranscriptionally to the Balbiani ring pre-mRNA in an intron-independent manner and accompanies the BR mRNP to the nuclear pore. Curr. Biol., 12, 859–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak L., Gopal,G., Yoon,J.H., Sauna,Z.E., Ambudkar,S.V., Thakurta,A.G. and Dhar,R. (2002) Elf1p, a member of the ABC class of ATPases, functions as a mRNA export factor in Schizosacchromyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 33580–33589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengyel J.A. and Penman,S. (1977) Differential stability of cytoplasmic RNA in a Drosophila cell line. Dev. Biol., 57, 243–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libri D., Dower,K., Boulay,J., Thomsen,R., Rosbash,M. and Jensen,T.H. (2002) Interactions between mRNA export commitment, 3′-end quality control and nuclear degradation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 8254–8266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linder P. and Stutz,F. (2001) mRNA export: travelling with DEAD box proteins. Curr. Biol., 11, R961–R963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo M.L., Zhou,Z., Magni,K., Christoforides,C., Rappsilber,J., Mann,M. and Reed,R. (2001) Pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA export linked by direct interactions between UAP56 and Aly. Nature, 413, 644–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orphanides G., Wu,W.H., Lane,W.S., Hampsey,M. and Reinberg,D. (1999) The chromatin-specific transcription elongation factor FACT comprises human SPT16 and SSRP1 proteins. Nature, 400, 284–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R. and Hurt,E. (2002) A conserved mRNA export machinery coupled to pre-mRNA splicing. Cell, 108, 523–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segref A., Sharma,K., Doye,V., Hellwig,A., Huber,J., Luhrmann,R. and Hurt,E. (1997) Mex67p, a novel factor for nuclear mRNA export, binds to both poly(A)+ RNA and nuclear pores. EMBO J., 16, 3256–3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser K. and Hurt,E. (2000) Yra1p, a conserved nuclear RNA-binding protein, interacts directly with Mex67p and is required for mRNA export. EMBO J., 19, 410–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser K. and Hurt,E. (2001) Splicing factor Sub2p is required for nuclear mRNA export through its interaction with Yra1p. Nature, 413, 648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser K. et al. (2002) TREX is a conserved complex coupling transcription with messenger RNA export. Nature, 417, 304–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutz F., Bachi,A., Doerks,T., Braun,I.C., Séraphin,B., Wilm,M., Bork,P. and Izaurralde,E. (2000) REF, an evolutionary conserved family of hnRNP-like proteins, interacts with TAP/Mex67p and participates in mRNA nuclear export. RNA, 6, 638–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainberg I.E., Dower,K. and Rosbash,M. (2000) Nuclear export of heat-shock and non-heat-shock mRNA occurs via similar pathways. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 3996–4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegand H.L., Coburn,G.A., Zeng,Y., Kang,Y., Bogerd,H.P. and Cullen,B.R. (2002) Formation of Tap/NXT1 heterodimers activates Tap-dependent nuclear mRNA export by enhancing recruitment to nuclear pore complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie G.S., Zimyanin,V., Kirby,R., Korey,C., Francis-Lang,H., Van Vactor,D. and Davis,I. (2001) Small bristles, the Drosophila ortholog of NXF-1, is essential for mRNA export throughout development. RNA, 7, 1781–1792. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Bogerd,H.P., Wang,P.J., Page,D.C. and Cullen,B.R. (2001) Two closely related human nuclear export factors utilize entirely distinct export pathways. Mol. Cell, 8, 397–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenklusen D., Vinciguerra,P., Strahm,Y. and Stutz,F. (2001) The yeast hnRNP-like proteins Yra1p and Yra2p participate in mRNA export through interaction with Mex67p. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 4219–4232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenklusen D., Vinciguerra,P., Wyss,J.C. and Stutz,F. (2002) Stable mRNP formation and export requires cotranscriptional recruitment of the mRNA export factors Yra1p and Sub2p by Hpr1p. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 8241–8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]