Abstract

Delayed dispersal, where offspring remain with parents beyond the usual period of dependence, is the typical route leading to formation of kin-based cooperative societies. The prevailing explanations for why offspring stay home are variation in resource wealth, in which offspring of wealthy parents benefit disproportionately by staying home, and nepotism, where the tendency for parents to be less aggressive and share food with offspring makes home a superior place to wait to breed. These hypotheses are not strict alternatives, as only wealthy parents have sufficient resources to share. In western bluebirds, Sialia mexicana, sons usually delay dispersal until after winter, gaining feeding advantages through maternal nepotism in a familial winter group. Experimentally reducing resource wealth (mistletoe) by half on winter territories caused sons to disperse in summer, even though their parents remained on the territory during the winter. Only 8% of sons remained with their parents on mistletoe-removal territories compared to 50% of sons on control territories (t9,10=3.33, p<0.005). This study is the first to demonstrate that experimentally reducing wealth of a natural food resource reduces delayed dispersal, facilitating nepotism and family-group living. The results clarify the roles of year-round residency, resource limitation and relative wealth outside the breeding season in facilitating the formation of kin-based cooperative societies.

Keywords: dispersal, cooperative breeding, mistletoe, bluebird, resource wealth

1. Introduction

Cooperation has presented an evolutionary puzzle since Darwin's early attempts to reconcile apparent altruism with his theory of natural selection (Darwin 1859, pp. 236–238). In birds, cooperation usually takes the form of cooperative brood care, with retained offspring helping to feed siblings or half-siblings at their parents' nest (Brown 1987). This form of helping arises via two steps: staying home into the next breeding season, followed by delayed breeding to help parents (Emlen 1982; Koenig et al. 1992). Territorial inheritance, territory budding and dispersal onto adjacent territories often follow delayed dispersal, leading to the formation of genetic dynasties localized in space (Emlen 1995; Dickinson & Hatchwell 2004; Ekman et al. 2004). As living near relatives provides opportunities for continuation of kin-biased social behaviours even after offspring have begun to breed on their own (Dickinson & Hatchwell 2004), determining which factors promote delayed dispersal is of fundamental significance to understanding the evolution of kin-biased cooperation (Ekman et al. 2004).

In his theoretical treatment of the evolution of families, Emlen (1995) argued that families should be inherently unstable with offspring making opportunistic choices to increase their fitness as new situations arise. Because offspring born to relatively poorer families should be more likely to disperse, he also predicted that stability should be greatest when family groups control high-quality resources. If wealth promotes delayed dispersal and a tendency for offspring to maintain contact with parents after leaving home, then variation in wealth should ultimately lead to kin-biased cooperation and proliferation of genetic dynasties from wealthier families within a population.

Hypotheses for the evolution of delayed dispersal focus on two key benefits for offspring that stay home: (i) prolonged brood care (nepotism, parental facilitation) (Brown 1987; Ekman & Griesser 2002) and (ii) access to resources (wealth, quality territories) (Hannon et al. 1987; Stacey & Ligon 1987, 1991). Prolonged brood care can confer advantages to delayed dispersers regardless of variation in resource wealth, but is tied to resource wealth in that wealthier parents can better afford to share resources (Ekman & Rosander 1992). Similarly, if variation in resource abundance accentuates the relative benefits of staying on high-quality territories then delayed dispersers can increase their fitness by staying, whether or not parents exhibit nepotism (Ekman & Griesser 2002). In this sense, the two hypotheses are not strict alternatives, nor are they necessarily inter-dependent.

Empirical studies of Siberian Jays (Perisoreus infaustus) support the idea that offspring staying at home experience reduced aggression at feeding sites (Ekman & Griesser 2002) and are favoured over immigrants by parental vigilance and alarm calling (Griesser 2003; Griesser & Ekman 2004). Field studies of dispersal patterns in two species of cooperatively breeding birds support the hypothesis that variance in territory quality favours offspring that delayed dispersal and remain on high-quality territories (Stacey & Ligon 1987; Komdeur 1992). Although past studies have examined population-wide differences in delayed dispersal as a function of parental presence (Ekman & Griesser 2002), habitat quality (Russell 2001) and food supplementation (Cochran & Solomon 2000), we are aware of no prior study that has directly manipulated resource abundance on individual territories to test the effects of variation in territory quality on delayed dispersal. Here, we perform a critical test of the importance of resource abundance for delayed dispersal and prolonged brood care in a single species, the western bluebird.

In central California, western bluebirds live in stable winter groups, which typically form when sons remain on their natal territory with their parents (Kraaijeveld & Dickinson 2001). Daughter-biased dispersal occurs in late summer, when dispersing offspring are replaced by female and, less commonly, male immigrants. Western bluebirds possess three attributes that allow isolation of factors critical to testing the importance of territory quality in facilitating delayed dispersal. First, although factors favouring delayed dispersal and helping behaviour are tightly coupled in most cooperative breeders, they are separable in western bluebirds, because sons delaying dispersal until after winter only rarely remain home to become helpers during the breeding season (Dickinson et al. 1996; Dickinson 2004). Second, western bluebird families hold winter territories based on a discrete, measurable, winter resource: oak mistletoe (Phoradendron villosum), which can be quantified and manipulated to determine the importance of resource abundance (Kraaijeveld & Dickinson 2001). Mistletoe berries are a critical winter resource as evidenced by the presence of seeds in 100% of faecal samples of 18 birds collected from 4 November 2004 to 29 January 2005. Opportunities for large-scale manipulation of a critical, natural food resource are rare, and manipulation of a natural food supply is unprecedented in studies of delayed dispersal. Third, in central California, mistletoe berries mature and become edible only after late summer dispersal has already taken place. Because mistletoe berries are not available until October, after the dispersal decisions are made, we can rule out the possibility that an experiment designed to examine the impact of resources on dispersal inadvertently examined the impact of resources on survival.

In western bluebirds, site fidelity of pairs year-to-year and the long-term persistence of mistletoe permit the accurate estimation of a family's mistletoe holdings needed to experimentally manipulate winter food abundance or ‘wealth’ (Kraaijeveld & Dickinson 2001). Systematic colour-banding of immigrant adults and nestlings each year provides needed information on familial relationships. We tested the importance of territory quality versus prolonged brood care by removing half the mistletoe (by volume) on experimental territories for comparison with sham control territories, occupied by researchers with ladders. Given that mean winter group size is five birds (Kraaijeveld & Dickinson 2001), removing 50% of a pair's mistletoe should leave enough mistletoe on average to support parents through the winter.

Although the prolonged brood care and territory quality hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, mistletoe removal has the potential to determine whether territory quality plays an overriding role in providing the conditions that permit delayed dispersal. There are four possible outcomes of mistletoe removal: (i) if territory quality (resource wealth) plays a key role in delayed dispersal, even if that role is mediated through the benefits of prolonged brood care, removal of half the mistletoe on a territory should increase dispersal of sons without influencing the tendencies of their parents to stay for winter; (ii) if resources are not limiting but nepotism is the key reason why sons delay dispersal, parents and offspring on mistletoe-removal territories should remain, possibly increasing their holdings by accessioning additional space and mistletoe, but delayed dispersal should not be affected; (iii) if resources are limiting and the benefits of delayed dispersal for offspring outweigh the benefits of staying for parents, then parents should leave mistletoe-reduced territories to winter elsewhere and their offspring should stay; and (iv) if 50% mistletoe removal creates an absolute insufficiency of resources, then both parents and offspring should disperse from mistletoe-removal territories.

2. Material and Methods

(a) Population monitoring

This research is based upon a continuing nest-box study of colour-banded western bluebirds begun at Hastings Reserve and Oak Ridge Ranch, Carmel Valley, California, USA in 1983 and expanded to include Rana Creek Ranch in 2001. General methods on population monitoring can be found in prior publications (Dickinson et al. 1996).

(b) Behavioural measures of aggression and nepotism

We observed interactions at feeders to quantify nepotism as feeding tolerance (reduced aggression) using direct observation and videotaped watches initiated 1–2 months after winter group formation in the period from 1 November to 15 January during the winters beginning 2002–2004. Because we used mealworm feeders to assess aggression, and did not want to disrupt the mistletoe-removal experiment by supplementing experimental or control territories, we restricted our observations in the winters of 2003 and 2004 to territories not involved in the experiment. Our data include measures of aggression for 134 dyads of breeders and hatch-year birds of both sexes from a total of 26 winter groups.

Mealworm feeders consisted of plastic weighing trays (Fisher Cat. No. 2-202D) placed on plywood platforms (1600 cm2) on the winter territories and monitored for 1–2 h per watch to examine interactions and food intake. A share (10–30 g) of mealworms was added to the feeder at the start of each watch and the remaining worms weighed and removed afterwards. During the first winter, 2001–2002, we used open trays, but during the next two winters we cut the corner off a second dish and placed it over the top to restrict the access of birds to one corner of the feeding dish, facilitating video identification. We collected a mean of 498±45 s.e.m. min of observation per group (range 60–945 min). The numbers and durations of watches varied with group size (3–13 birds), because larger groups necessitated longer observation periods to obtain adequate data on all dyads of former breeders and first-winter birds.

We recorded the number of times each dyad of birds (breeding pair from spring and first-winter juvenile) was on the feeder together and calculated an index of aggression, dividing the number of times the former breeder was aggressive to the younger bird by the total number of times they were together on the feeder. Bird A was aggressive to bird B when it engaged in the following behaviours: (i) lunging, in which bird A moved (walked or hopped) toward bird B, causing bird B to walk, hop, or fly away; (ii) displacement, in which bird A landed within 10 cm of bird B, causing bird B to leave the feeding platform or to hop >10 cm away; (iii) chases, when bird B approached the feeding platform within 0.5 m and was chased by bird A within 2 s; and (iv) aborted landings, where bird B approached the platform within 10 cm and bird A lunged or hopped towards B, such that B did not land. To assess the impact of nepotism on food intake, we counted the number of mealworms each bird obtained while on the feeder and calculated the first-winter bird's share of mealworms relative to the mealworm intake of the territory's breeding female from the prior spring (only female breeders exhibited nepotism towards sons). This index, which involved dividing the first-winter male's mealworm intake by his intake combined with that of the female (former) breeder, circumvents effects of variation in feeding rates with weather, group size and group composition, all of which will influence the intensity of feeding competition and food sharing within groups.

The test for feeding tolerance was a generalized linear model (GLM) with status of the subordinate bird (first-winter offspring or first-winter immigrant) as a fixed factor, year as a random factor and proportion of interactions, where the former breeder was aggressive as the response variable. Analysis of share of feeding compared sons with immigrant males using a GLM. Proportions were angularly transformed.

(c) Mistletoe mapping

During 2001–2003, mistletoe-parasitized trees were located by traversing the area within 200 m of each nest-box after leaf drop and before trees leafed out again. Trees (n=3377) were marked with uniquely numbered aluminium tree tags and photographed next to a reference stake using a digital camera. Trees were localized in space using differential global positioning system (GPS; Garmin ABX-3 with 12XL) and mistletoe clumps were counted and classified into six size categories (diameter <20, 20–50, 50–75, 75 cm; 1, 1–1.5, >1.5 m). The volume of mistletoe was calculated for the first five categories using the formula for the volume of a sphere with radius 10, 20, 35, 60 and 75 cm and summed to obtain a total mistletoe volume for each tree. Clumps measuring >1.5 m, the sixth category, tended to be elongate and their volume was approximated as the sum of the volume for two 75 cm diameter clumps.

(d) Territory mapping

Territory maps were created in Arcview based upon observation of the breeding pair's movements throughout the breeding season in spring 2003. To create maps we combined independent data points placed on the map during periodic visits to the territory with points obtained during 1–2 h focal pair watches. The territory boundary was the minimum convex polygon using 100% of the points, excluding points identified as territorial intrusions eliciting a chase by a neighbouring bird. A pair's mistletoe holdings included the trees found within the minimum convex polygon and any unclaimed trees within 20 m of the perimeter of the polygon and less than one-third of the way to the line demarcating an adjacent, mapped, territory. In the majority of cases, territory maps abutted each other.

(e) Mistletoe-removal experiment

In summer 2003, we removed half of the mistletoe by volume from 13 experimental territories matched to 13 sham control territories by original mistletoe volume and site (n=26 spring territories in total) (figure 1). Dyads of male relatives nesting next door to each other were assigned the same treatment (removal or control) and paired to similar dyads receiving the alternative treatment, because male relatives sometimes combine territories to form a single winter group. The matched-pairs design ensured that there were no systematic biases in mistletoe wealth or territory size between removal and control territories and reduced random between-treatment variance. As anticipated, failure of some pairs to produce offspring and variability in whether relatives breeding adjacent to each other wintered separately or together meant we could not carry the matched design into a matched pairs analysis. We instead used unpaired t-tests, GLMs and the Fisher exact test. Consolidation of adjacent territories held by relatives and failure of some nests to produce sons reduced the sample size from 26 to 17–22, depending on the analysis.

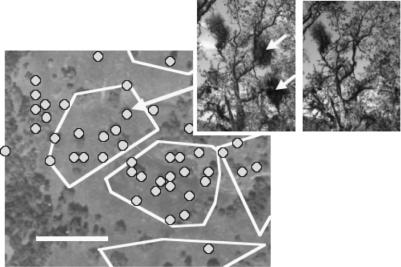

Figure 1.

Example of spring territory occupied by western bluebird pair, showing 100% minimum convex polygon (line), dispersion of mistletoe-parasitized oak trees (dots) and photographs of one tree before (left) and after (right) mistletoe removal. Arrows indicate large (1.5 m tall) clumps that were removed. Scale bar, 100 m.

Experimental and control nests were protected from predators using garden netting furled around the box support and chicken wire baskets over nest entrances. All mistletoe removal and control nests fledged young. Mistletoe-removal and sham control treatments were conducted between 9 June and 4 August 2003, and were completed prior to offspring independence. Removal involved clipping branches of mistletoe until only the burl and haustoria (root system) remained intact. The majority of clumps could be reached from the ground using extendable, aluminium trimmers with a rope closure mechanism. Mistletoe clumps high in the trees were reached using ladders or climbing ropes and ascenders. We made an effort to remove clumps evenly throughout a territory, so that all, rather than just part of the territory was affected by the manipulation. The volume of mistletoe removed ranged from 5 m3 to 90 m3 (mean 34±9 m3) and a mean of 52±1% s.e.m. (range 42–58%) of the mistletoe was removed from experimental territories. Sham control territories were occupied by researchers with ladders, who moved among trees and remained stationary beneath them for time periods equivalent to the time required to remove mistletoe on the corresponding experimental territory.

(f) Censusing and behavioural observation

Winter groups are highly stable and members travel as a cohesive group when they leave the territory to forage for water or less clumped berry crops off the defended territories (e.g. toyon, Heteromeles arbutifolia). Changes in group composition were assessed by regular censusing of each territory for a minimum of 3 h per month from 15 July 2003 to 28 February 2004. Any bird seen in a group after 1 October 2003 was given winter group membership. Using this method groups were stable, except for the apparent mortality of 1–2 retained offspring per month over the course of the winter. By January, 73% of 22 retained offspring still remained in their winter groups. Aggression (chases, displacements) and identities of participants were recorded during the summer censuses (15 July–1 September) to look for parental aggression, which might influence dispersal of offspring.

3. Results

(a) Evidence for prolonged brood care

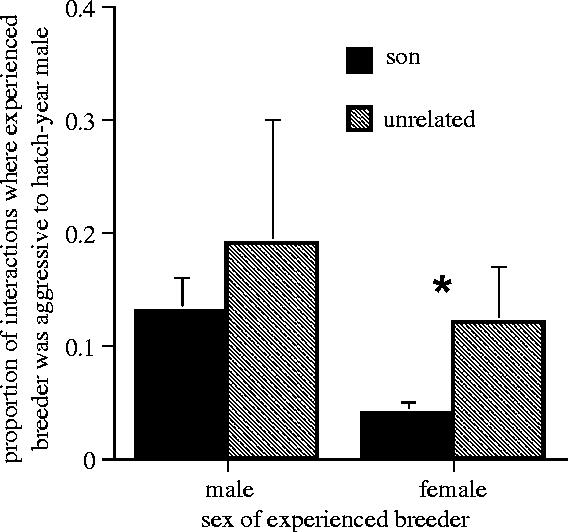

Sons benefit from prolonged brood care, which is sex-specific, with females (but not males) of the dominant pair behaving less aggressively to stay-at-home sons than to unrelated first-winter males that have joined their winter social group (figure 2, GLM, female breeder: F1,20=3336, p=0.01; male breeder: F1,33=0.9, p=0.5). This reduced aggression or feeding tolerance allowed sons to consume a greater proportion of the combined share of mealworms than was consumed by immigrant males (GLM, first-winter son: 0.57±0.04; immigrant first-winter male: 0.40±0.05, F1,27=258, p=0.01).

Figure 2.

Measures of aggression at mealworm feeders showing nepotism favouring sons by the dominant, breeder female, but not by the breeder male. The measures of aggression were the proportion of times the former breeder was aggressive to the young, hatch-year (first winter) bird out of the total number of times they were together on the feeder station. Black bar is for son and grey bar for unrelated immigrant male. Error bars, +1 s.e.

(b) Impact of 50% mistletoe removal on delayed dispersal, potential for nepotism and group membership

When the volume of mistletoe was experimentally reduced by 50%, territories were less likely to retain fledged sons and retained a lower proportion of sons on average than did sham control territories (table 1). In contrast, mistletoe-reduced territories were not statistically less likely to retain daughters and did not retain a lower proportion of daughters than sham controls. The mean proportion of sons delaying dispersal and remaining with their parents in winter groups was more than five times as high on sham control as experimental removal territories, indicating that mistletoe resource abundance is a critical determinant of delayed dispersal of sons, the sex that usually stays home. Dispersers not only left their family groups; they were not seen on the study area their first winter and did not return to breed in spring of 2004 or 2005. Because mistletoe berries are not yet available as food during late summer, when offspring disperse, there is no reason to expect differential survival of experimental and control offspring.

Table 1.

Effects of mistletoe removal on western bluebirds' tendency to stay on territory for winter and per capita mistletoe volume for winter groups.

| response variables | mistletoe removed (n) | sham control (n) | test statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| proportion of territories retaining sons | 0.11 (9) | 0.80 (10) | Fisher exact | 0.005 |

| proportion of territories retaining daughters | 0.30 (10) | 0.36 (11) | Fisher exact | 0.56 |

| mean proportion of sons retained | 0.08±0.08 (9) | 0.50±0.11 (10) | t=3.33 | 0.005 |

| mean proportion of daughters retained | 0.02±0.13 (10) | 0.17±0.08 (11) | t=0.37 | 0.71 |

| proportion of territories where parents stayed | 0.73 (11) | 0.82 (11) | Fisher exact | 0.50 |

| mean number of immigrant females attracted | 1.00±0.33 (11) | 1.09±0.41 (11) | t=0.17 | 0.87 |

| mean per capita mistletoe (volume) (m3) | 7.7±1.9 (9) | 9.2±3.8 (8) | t=0.32 | 0.75 |

Means presented ±s.e.m.

Disappearance of sons from mistletoe-reduced territories was not accompanied by simultaneous disappearance of parents, demonstrating that devaluation of resource wealth played a more critical role in driving sons' dispersal than did the potential for continuing interaction with parents. Most parents remained on their territories for winter, and their retention was not influenced by mistletoe removal (table 1). The volume of mistletoe remaining was lower for groups where the parents disappeared than for groups where the parents stayed for the winter (15.9±6.5 versus 43.9±8.9 m3, t5,17=2.45, p=0.021), indicating that parents migrated or dispersed if their mistletoe wealth was very low, but their departure did not depend upon whether they were on a removal or control territory (logistic regression: Wald=0.256, d.f.=1, n=22, p=0.61).

The critical importance of resources in facilitating delayed dispersal was also supported by the results of a GLM with retention of sons and daughters as response variables and experimental treatment and presence of parent(s) as fixed factors. In this analysis the effect of mistletoe removal had a statistically significant effect on retention of sons (F1,14=5.6, p=0.03), but not daughters (F1,14=0.17, p=0.68). Interaction effects and effects of parents were not statistically significant for either sex.

Even though mistletoe removal decreased retention of sons on their natal territories, it did not reduce the attraction of new, immigrant females into winter groups (table 1). Also, because fewer sons stayed on mistletoe-reduced territories, per capita mistletoe volume did not differ between removal and control treatments during the winter following removal (table 1). This suggests that females joining groups on mistletoe-reduced territories did not suffer reduced access to winter food compared to females joining control groups. These results also provide evidence that resources were sufficient to allow sons to stay, provided that no new females joined the group, and that their departure was a consequence of relative wealth rather than absolute insufficiency of resources.

Did sons electively disperse or were they evicted by parents due to the increased costs of food-sharing on mistletoe-reduced territories? Aggression towards offspring was extremely low during the summer, when dispersal was occurring, with only 15 instances of aggression observed during 322 h of observation of 26 groups. Only one of nine interactions between individuals of known age and status involved aggression by a breeding adult towards a juvenile. However, the hypothesis of parental eviction is difficult to falsify, because eviction could occur as a single, very intense, event that would be missed even with extensive sampling.

4. Discussion

This experiment demonstrates that resource wealth has a critical impact on delayed dispersal of young and supports the idea that relative wealth of monopolizable resources is the starting point for the evolution of philopatry and kin-based sociality (Emlen 1995). Alternative explanations for the results we obtained are implausible. Survival was not confounded with dispersal, because dispersal of sons occurred in late summer, well before mistletoe produced any berries. This suggests that dispersal of sons was caused by a perceived reduction in mistletoe volume on the part of evicting parents or dispersing offspring, and this perception is probably based on visual assessment. It is unlikely that 50% mistletoe removal created a roost site shortage, because western bluebird groups roost communally and all mistletoe-removal territories had nest-boxes, natural cavities and remaining mistletoe clumps for roosting. Increased visibility to predators is also an unlikely explanation, because adult survival and retention were similar for the treatment and control groups.

Our observation that sons dispersed from mistletoe-reduced territories even when their parents remained for the winter suggests that resource wealth plays a critical, but not necessarily singular, role in delayed dispersal. While parental nepotism may provide important benefits, these benefits are contingent upon the abundance of resources available to share (Ekman et al. 2004). As yet, it is unclear whether sons left voluntarily or were evicted by their parents due to increased costs of sharing food on mistletoe-reduced territories. It is even possible that a conflict of interest between male and female parents influences offspring dispersal, with nepotistic female parents more likely to favour sons staying home. Although sons left their parents to disperse when mistletoe was reduced, this experiment did not address the question of whether sons will remain for the winter without their parents, a critical test of the importance of nepotism (Ekman & Griesser 2002). This question can only be addressed by removing parents from intact territories.

Our finding that delayed dispersal is favoured on high-quality territories with abundant winter resources in western bluebirds, which only rarely have helpers, supports the hypothesis that direct fitness benefits accruing via personal survival and reproduction can generate patterns of delayed dispersal that lead to opportunistic, kin-directed cooperative breeding (Dickinson 2004). In this, our experimental study is in concordance with the results of observational studies in a diversity of animals, including humans, where correlative evidence has linked resources to male philopatry and male-biased inheritance (Towner 2001). Furthermore, this study has broad significance for understanding animal dispersal by providing unambiguous support for the hypothesis that variation in the distribution of resources and territory quality outside the breeding season play decisive roles in delayed dispersal, social group composition and partial migration within populations of birds. Finally, impacts of mistletoe abundance on western bluebird social structure and demography have significant conservation implications. Rapid conversion of California's oak savannah to vineyard, to the extent that it involves clearing of deciduous, mistletoe-bearing oaks, will disrupt bluebird family structure, which could lead to reduced winter survival, exacerbating western bluebird declines in California.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Vittorio Baglione, Tim Clutton-Brock, Nick Davies, Walter Koenig, and anonymous reviewers for advice on the manuscript and many volunteer postgraduate interns for help censusing birds, conducting sham controls, mapping trees, monitoring nests and keeping the population banded over the years. In the years of this experiment, L. Bernsten, K. Eldridge, M. Euparadorn, K. Greenwald, J. Gunst, D. Kleiber, C. Mitra, D. Moseley, A. Reinmann, J. Rose, K. Rudolph, D. Shizuka, E. Westerman and D. Whitcomb conducted nepotism watches and monitored nests and winter groups. James Rose assisted with clipping mistletoe. Funding was provided by NSF grant no. IBN-009702 (to JLD) and by A & S whose generous, anonymous and much appreciated private donation continues to support avian research at Hastings Reserve.

Footnotes

Present address: Marine Turtle Research Group, Centre for Ecology and Conservation, University of Exeter in Cornwall, Tremough Campus, Penryn TR10 9EZ, UK.

References

- Brown J.L. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1987. Helping and communal breeding in birds. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran G, Solomon N. Effects of food supplementation on the social organization of prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) J. Mammol. 2000;81:746–757. 10.1644/1545-1542(2000)081%3C0746:EOFSOT%3E2.3.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. On the origin of species. John Murray; London: 1859. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson J.L. Local breeding competition and a female shortage explain helping behavior and facultative sex ratio adjustment in western bluebirds. Anim. Behav. 2004;68:233–238. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.07.022 [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson J.L, Hatchwell B.J. Fitness consequences of helping behavior. In: Koenig W, Dickinson J.L, editors. Evolution and ecology of cooperative breeding in birds. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2004. pp. 48–66. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson J.L, Koenig W.D, Pitelka F.A. Fitness consequences of helping behavior in the western bluebird. Behav. Ecol. 1996;7:168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman J, Griesser M. Why offspring delay dispersal: experimental evidence for a role of parental tolerance. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002;269:1709–1714. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2082. 10.1098/rspb.2002.2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman J, Rosander B. Survival enhancement through food sharing: a means for parental control of natal dispersal. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1992;42:117–129. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(92)90008-h. 10.1016/0040-5809(92)90008-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman J, Dickinson J.L, Hatchwell B.J, Griesser M. Delayed dispersal. In: Koenig W, Dickinson J.L, editors. Evolution and ecology of cooperative breeding in birds. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2004. pp. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

- Emlen S.T. The evolution of helping. I. An ecological constraints model. Am. Nat. 1982;119:29–39. 10.1086/283888 [Google Scholar]

- Emlen S.T. An evolutionary theory of the family. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:8092–8099. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesser M. Nepotistic vigilance behaviour in Siberian jay parents. Behav. Ecol. 2003;14:246–250. 10.1093/beheco/14.2.246 [Google Scholar]

- Griesser M, Ekman J. Nepotistic alarm calling in the Siberian jay, Perisoreus infaustus. Anim. Behav. 2004;67:933–939. 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.09.005 [Google Scholar]

- Hannon S.J, Mumme R.L, Koenig W.D, Spon S, Pitelka F.A. Poor acorn crop, dominance, and decline in numbers of acorn woodpeckers. J. Anim. Ecol. 1987;56:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig W.D, Pitelka F.A, Carmen W.J, Mumme R.L, Stanback M.T. The evolution of delayed dispersal in cooperative breeders. Q. Rev. Biol. 1992;67:111–150. doi: 10.1086/417552. 10.1086/417552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komdeur J. Importance of habitat saturation and territory quality for evolution of cooperative breeding in the Seychelles warbler. Nature. 1992;358:493–495. 10.1038/358493a0 [Google Scholar]

- Kraaijeveld K, Dickinson J.L. Family-based winter territoriality in western bluebirds: the structure and dynamics of winter groups. Anim. Behav. 2001;61:109–117. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2000.1591. 10.1006/anbe.2000.1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell A.F. Dispersal costs set the scene for helping in an atypical avian cooperative breeder. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2001;268:95–99. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1335. 10.1098/rspb.2000.1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey P.B, Ligon J.D. Territory quality and dispersal options in the acorn woodpecker, and a challenge to the habitat-saturation model of cooperative breeding. Am. Nat. 1987;130:654–676. 10.1086/284737 [Google Scholar]

- Stacey P.B, Ligon J.D. The benefits-of-philopatry hypothesis for the evolution of cooperative breeding: variation in territory quality and group size effects. Am. Nat. 1991;137:831–846. 10.1086/285196 [Google Scholar]

- Towner M.C. Linking dispersal and resources in humans: life history data from Oakham, Massachusetts (1750–1850) Hum. Nat. 2001;4:321–349. doi: 10.1007/s12110-001-1002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]