Abstract

Natural populations vary tremendously in their susceptibility to infectious disease agents. The factors (environmental or genetic) that underlie this variation determine the impact of disease on host population dynamics and evolution, and affect our capacity to contain disease outbreaks and to enhance resistance in agricultural animals and disease vectors. Here, we show that changes in the environmental conditions under which female Daphnia magna are kept can more than halve the susceptibility of their offspring to bacterial infection. Counter-intuitively, and unlike the effects typically observed in vertebrates for transfer of immunity, mothers producing offspring under poor conditions produced more resistant offspring than did mothers producing offspring in favourable conditions. This effect occurred when mothers who were well provisioned during their own development then found themselves reproducing in poor conditions. These effects likely reflect adaptive optimal resource allocation where better quality offspring are produced in poor environments to enhance survival. Maternal exposure to parasites also reduced offspring susceptibility, depending on host genotype and offspring food levels. These maternal responses to environmental conditions mean that studies focused on a single generation, and those in which environmental variation is experimentally minimized, may fail to describe the crucial parameters that influence the spread of disease. The large maternal effects we report here will, if they are widespread in nature, affect disease dynamics, the level of genetic polymorphism in populations, and likely weaken the evolutionary response to parasite-mediated selection.

Keywords: Daphnia, Pasteuria ramosa, maternal effects, genotype by environment interactions

1. Introduction

The phenotype of an individual is influenced not only by its own genotype and the environment it experiences, but also by the environmental experience and genotype of other individuals (Kirkpatrick & Lande 1989; Bernardo 1996; Rossiter 1996; Mousseau & Fox 1998; Wolf et al. 1998; Bateson et al. 2004). Maternal effects are a particularly widespread example of this, having been reported from a wide range of taxa in response to various factors, including nutrients, mate quality and the presence of biological enemies (Bernardo 1996; Rossiter 1996; Mousseau & Fox 1998; Wolf et al. 1998; Agrawal et al. 1999; Cunningham & Russell 2000). Moreover, maternal effects are often adaptive, empowering offspring with, for example, optimal life history strategies, mate choice or improved capacity to avoid predation (Gliwicz & Guisande 1992; Bernardo 1996; Reznick et al. 1996; Cleuvers et al. 1997; Mousseau & Fox 1998; Agrawal et al. 1999; Alekseev & Lampert 2001; Prasad et al. 2003).

Maternal effects on disease susceptibility are well studied in vertebrates, where offspring susceptibility can be reduced by maternal transfer of acquired immune factors such as antibodies (e.g. Grindstaff et al. 2003). Remarkably few studies have investigated maternal effects on disease susceptibility in invertebrates, possibly because invertebrates are usually considered to have only innate immunity and, therefore, to be naive at each new encounter with pathogens (Roitt 1997). However, the transgenerational transfer of immunity has been shown in invertebrates (e.g. the shrimp, Penaeus monodon (Huang & Song 1999) and the ‘waterflea’, Daphnia magna (Little et al. 2003)), indicating a potentially large role for maternal effects in parasite resistance in invertebrates.

Here, we examine the role of variation in both the maternal and offspring environment in determining susceptibility of D. magna to the sterilizing bacterial pathogen Pasteuria ramosa. The D. magna–P. ramosa host–parasite system shows considerable genetic variation for host resistance in field and laboratory studies, but natural selection on this variation has proven difficult to predict (Little 2002; Mitchell et al. 2004). As Daphnia show phenotypic plasticity in many traits, often with genotype by environment (G×E) interactions (e.g. Gliwicz & Guisande 1992; Agrawal et al. 1999; Boersma et al. 1999; Mitchell & Lampert 2000), we hypothesized that environmental variation would be playing a large role in the expression of disease phenotypes in this system (Mitchell et al. 2004, 2005). Our results support this hypothesis, but in some unexpected ways.

2. Material and methods

(a) Host genotypes

Two clones (referred to as clones 25 and 85) were used in these experiments. In two previous experiments, clone 25 tended to have lower infection rates than clone 85 under a maternal regime of constant good conditions without parasite exposure (Mitchell et al. 2004, 2005), and these differences fell within the normal range found in nature. In one experiment involving 86 clones from the population from which these two clones came, infection rates varied between 0.33 and 1.0 (clone 25: 0.54, clone 85: 0.78; Mitchell et al. 2004). In another experiment, involving 10 clones from this population and a range of temperatures and food levels, infection rates at comparable conditions to those used here varied from 0.47 to 0.79 (clone 25: 0.61, clone 85: 0.79; Mitchell et al. 2005).

(b) Experimental overview

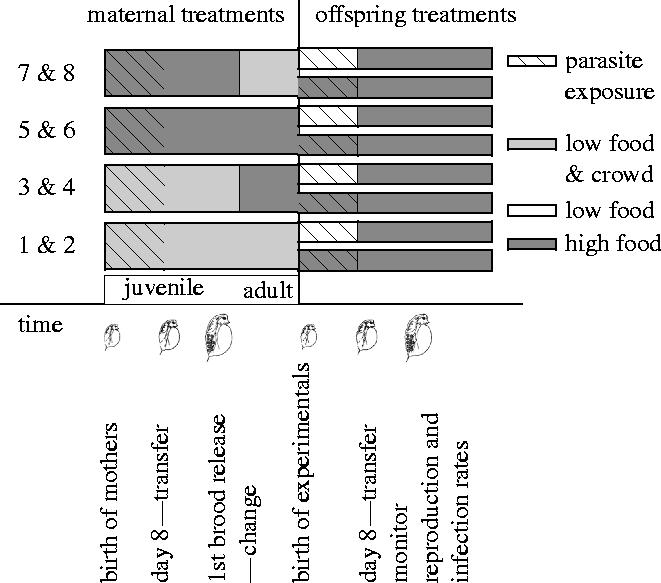

We tested the offspring infection rates of the two host clones after mothers were exposed to good or stressful conditions as ‘juveniles’ or as reproductive ‘adults’ in a fully cross-factored design (figure 1). In the good environment, Daphnia were uncrowded and maintained at high food levels with regular changes of freshwater. In the stressful environment, females were crowded at low-food levels. Half the animals in the maternal generation were exposed to the bacteria. All offspring were then exposed to parasites in one of two environments, low or high food, and then reared in a high-food environment to determine infection outcome (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The Experimental set up. There were eight maternal treatments (1–8), consisting of four environmental conditions, each represented by a bar comprising two treatments: with (even numbers) or without (odd numbers) parasites during the exposure protocol during the first seven days. The batch control populations are not shown, but were raised under good conditions in 3 litres of water without a parasite exposure protocol. Mothers were raised under good or stressful environments. The ‘juvenile’ maternal stage lasted until the release of the first brood, at which point mothers either remained in the same environment or were switched to the other environment for the ‘adult’ stage. Good conditions were high food and frequent water change; stress conditions were low food and crowding. Offspring from the fourth broods (i.e. the third broods after the release of the first broods and change in environmental conditions) were used in the assays of offspring susceptibility to P. ramosa. Maternal broods were split into two replicates that were given either low- or high-food conditions and all offspring were exposed to parasites. In both the maternal and offspring generations, parasite exposure (shown as hatched lines) occurred during actual juvenile development, from within 24 h of birth until day 7 at 20 °C. After the exposure period, offspring were monitored for reproduction and signs of infection.

(c) Pre-experimental generations

Ten independent replicates for each of the two clones were raised under good conditions at 20 °C for one generation (2 clones×10 replicates=20 grandmothers). Eight maternal treatment lines per grandmother replicate were created with female neonates <24 h old from the second broods (2 clones×8 treatments×10 replicates=160 ‘mothers’). Water was made to a modified recipe (Mitchell et al. 2005) using de-ionized water and analytical grade chemicals to ensure standardization and reproducibility. Daphnia were fed Scenedesmus obliquus, a green alga cultured in chemostats with Chu B medium. The experiment was conducted as follows (figure 1).

(d) Maternal environments

Half the mothers were exposed to parasites (odd numbered maternal treatments), and the other half experienced the same protocol (see below) but without parasite spores (even numbered maternal treatments; figure 1). Parasite-exposed lines were not treated with antibiotics, so that experimental offspring were produced by females that were not sterilized despite exposure to parasites. After parasite exposure, mothers were transferred to 300 ml jars. Stress (S) treatments combined low food (1.5×107 cells per jar daily), crowding (20 juvenile females, culled to 10 females in the ‘adult’ period) and no water changes (allowing metabolites and offspring to accumulate) until two days before the offspring generation was isolated. Good (G) conditions were high food (3.5×107 cells per jar daily), 10 females and fresh water changes every 2 days. The maternal ‘juvenile’ period was set until the first brood was released, when half the mothers were switched to the other environment and half remained under the same conditions for the ‘adult’ environment. Mothers initially under stress were set up 6 days earlier than the good condition lines and controls as it takes longer to reach maturity, and this helped to synchronize the release of the offspring generation. However, as clutch release over so many replicates and such varied maternal conditions cannot be completely synchronized, the experiment was set up over 7 days (making seven ‘batches’).

To account for uncontrollable daily variation among batches, three control populations for each clone were maintained under good conditions in 3 l water. During the offspring infection experimental set-up, all neonates were removed daily to set up 12 replicates following the regime below (2 food levels×2 clones×3 replicates). The daily mean infection in the 12 controls was the covariate, called the control batch mean, in statistical analyses.

(e) Offspring generation

The offspring generation was isolated from approximately the maternal fourth brood, as this was the third brood released after the change to the ‘adult’ period, for which the ovaries were laid down in the instar following the environment change (figure 1).

Offspring were set up over 7 days as 160 maternal replicates under variable regimes are unsynchronized. Each maternal brood was split into two offspring replicates of 10 randomly assigned neonates <24 h old in a 60 ml jar and given either high or low food (figure 1). All offspring replicates were exposed to parasites using the same regime as for mothers (see below). Offspring were transferred to 300 ml jars on day 8, after which all offspring treatments received the same high-food level (3.5×107 cells per jar) to encourage parasite growth and prevent sterilization from resource limitation instead of parasitism. Water was changed and Daphnia were screened for reproduction and signs of infection under a dissecting microscope every 3 days from day 8. Reproduction rates and also, therefore, onset of sterility, had stabilized for most replicates by day 17 or 20. Infection first appeared by day 17 and infection rates within replicates stabilized by day 26, indicating that all Daphnia that had become infected during exposure were displaying symptoms. Once started, Daphnia continue to display symptoms of this disease, with increasing severity, until they die.

(f) Parasite exposure

Parasite spores were from a batch used in a previous study, where both spores and the clones used for propagating originated from the same population as these two clones (Mitchell et al. 2005). During parasite exposure in both generations, all replicates were raised for 7 days without a water change in 60 ml jars containing 50 ml water and 5 g sand. Parasite spores (1.2×105 spores per jar) were added on the first day to parasite exposure (P+) treatments (Only odd numbered maternal treatments but all offspring). Maternal environments, good or stress, were fully cross-factored with parasite exposure; all offspring were exposed to parasites. All replicates were stirred daily to resuspend spores in P+treatments. The feeding regime during parasite exposure was designed to promote encounter rates with spores, which must be ingested. In maternal lines, high food was 1.2×107 algal cells on day 1, 0.8×107 cells daily and low food was 1.2×107 algal cells on day 1, 0.8×107 cells on days 3 and 6. For the offspring generation, feeding rates during parasite exposure were high food: 1.2×107 cells per jar on days 1 and 3; 2×107 cells per jar on day 6; and low food: 1.2×107 cells per jar on days 1 and 6, and 0.6×107 cells per jar on day 3.

(g) Statistical analysis

Infection data from day 26 were analysed using the glimmix macro for Proc Mixed with binomial errors in SAS v.8 in the minimal model described in table 1. Adjusted Odds ratios (ODs) with Wald Confidence intervals were calculated using SAS Proc Logistic on models containing main effects: , where Ni/NT, number of infected females on day 26/total number of females in replicate; covariate, the control batch mean for day 26; parasite, presence or absence of parasites in maternal generation; offspring food, offspring food level (high or low) when exposed to parasites; treatment, the four maternal environment combinations, SS, SG, GG, GS.

Table 1.

Analysis of variance for the number of infections per replicate in two clones raised under differing maternal environments and two offspring food environments. The maternal environments (see figure 1) tested were fully crossed between good or stressed ‘juvenile’ (from birth to release of first offspring) or ‘adult’ environments and with maternal exposure or not to parasites (parasite). Offspring food levels were tested within maternal clutch, which was set as a random factor. The minimum model was run using glimmix for Proc Mixed in SAS v.8 with binomial errors: Number of infected females on day 26/total number of females in replicate=covariate+clone+maternal ‘juvenile’ environment+maternal ‘adult’ environment+‘juvenile’בadult’ maternal environments+parasite+clone×parasite+offspring food+clone×offspring food+maternal ‘adult’ environment×offspring food+parasite×offspring food+clone×parasite×offspring food, where covariate, is the batch mean for the proportion of infections in the control replicates, on day 26 and offspring food, offspring food level (high or low) when exposed to parasites.

| effect | df1,2 | F value | p |

| covariate | 1,170 | 18.64 | <0.0001 |

| clone | 1,129 | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| maternal juvenile environment | 1,137 | 2.04 | 0.16 |

| maternal adult environment | 1,153 | 26.46 | <0.0001 |

| juvenile×adult maternal environments | 1,135 | 18.59 | <0.0001 |

| parasite | 1,131 | 1.82 | 0.18 |

| clone×parasite | 1,130 | 0.07 | 0.79 |

| offspring food | 1,151 | 14.03 | 0.0003 |

| clone×offspring food | 1,152 | 0.31 | 0.58 |

| maternal adult environment×offspring food | 1,151 | 4.16 | 0.04 |

| parasite×offspring food | 1,152 | 1.68 | 0.20 |

| clone×parasite×offspring food | 1,152 | 7.88 | 0.006 |

3. Results

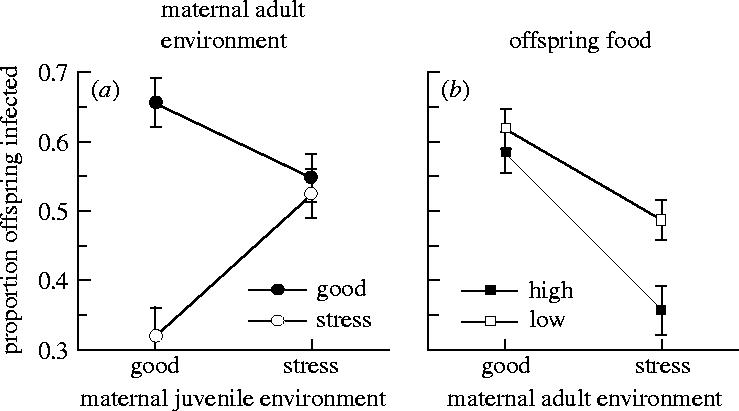

Maternal environment was a major determinant of offspring disease susceptibility (figure 2a; table 1). Offspring produced by mothers in crowded conditions with low food were less susceptible to parasites compared to those produced under good conditions (main effect of maternal adult environment: F1,153=26.46, p<0.0001; OD for offspring susceptibility: good versus stress: 1.98, CI 1.67–2.35). However, this main effect was strongly affected by the developmental environment and mainly due to mothers that had a good juvenile environment (figure 2a; juvenile×adult maternal environment interaction: F1,135=18.59, p<0.0001). Offspring were least susceptible to infection when their mothers had been well provisioned during their own development, but then experienced the stressful environment during adult reproduction (OD for susceptibility, continuously good versus good then stress: 4.09 CI 3.14–5.37).

Figure 2.

Effects of maternal and offspring environments on offspring infection rates, shown as least square means (LSM)±1 s.e. derived from analysis of variance. (a) Interaction effects of maternal ‘adult’ environment by the maternal ‘juvenile’ environmental conditions. (b) Interaction between maternal adult conditions and offspring food levels during parasite exposure.

The effects of maternal conditions revealed in this study were consistent across both host clones tested (clone× maternal adult environment interaction F1,138=0.07, p=0.8; clone×juvenile×adult maternal environment interaction F2,131=1.47, p=0.23).

Food effects in the offspring environment were also significant and were the opposite of that observed for maternal effects: offspring experiencing low-food conditions were more susceptible than those under high-food conditions (figure 2b; F1,151=14.03, p=0.0003). However, this effect was relatively small (OD for offspring susceptibility: high versus low 0.74, CI 0.62–0.87) compared to maternal effects, where offspring susceptibility was at least halved under some combinations of maternal environments (figure 2b). Offspring food effects were apparent when the maternal adult environment was stressful but not when the mothers were reproducing in good conditions (figure 2b, maternal adult environment×offspring food level interaction; table 1).

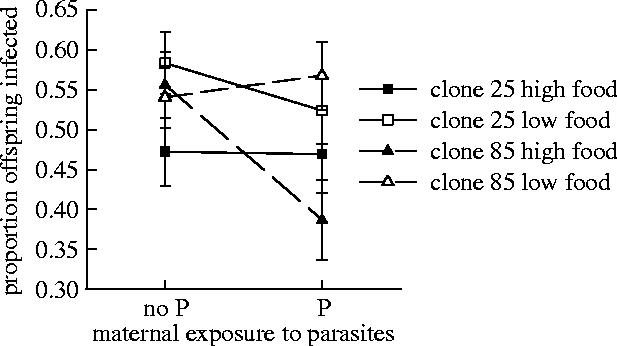

There was also an effect of maternal exposure to parasites on offspring susceptibility although the expression of this acquired protection was complex, and depended on both the host genotype and the food level experienced by offspring (figure 3, table 1; clone×parasite×food interaction F1,152=7.88, p=0.006). Following parasite exposure, mothers of one of the two clones (clone 85) produced better protected offspring, but this was only manifest when those offspring experienced high food throughout their lives. Maternal parasite exposure had no significant effect on the susceptibility of the offspring of the other clone (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of maternal and offspring environments on offspring infection rates, shown as LSM±1 s.e. derived from analysis of variance. Interaction between maternal exposure to parasites, offspring food level (high food, filled symbols; low food, open symbols) and clone (85 triangle and dashed line, 25 square and solid line).

4. Discussion

Few studies investigate maternal effects on disease susceptibility and, to our knowledge, this is the first in invertebrates to include maternal genetic effects. We show that offspring susceptibility to parasites depends on both the offspring and maternal environments, including complex interactions that can lead to non-intuitive outcomes. The results are consistent with maternal effects on other traits that depend on both maternal and offspring environments (Bernardo 1996; Rossiter 1996; Mousseau & Fox 1998; Wolf et al. 1998).

The effect of offspring environment was in line with general expectations of food levels on parasite susceptibility: offspring experiencing low-food conditions were more susceptible to infection (figure 2b). Offspring low-food conditions have a direct impact, such as on current ability and resources to mount an immune response. However, low-food conditions in the maternal environment had the opposite effect: reduced susceptibility (figure 2a). Here, maternal effects impact offspring traits indirectly rather than directly.

The reduced susceptibility of offspring from mothers under stressed or unpredictable conditions may be part of a general phenomenon by which Daphnia optimize their reproductive allocation strategy. We suspect this played a large part in this study as maternal brood sizes from which the offspring generation were set up varied enormously between maternal environments—from large broods under adult good conditions to very small broods and sexual resting eggs under adult stress conditions. Due to the scale of this experiment, we could not measure the neonates used to start the offspring generation, but length, weight, carbon and fat content analyses of neonates from the same ‘set-up’ brood in future experiments would determine whether offspring quality has contributed to the differences in susceptibility to parasites. In previous studies, Daphnia mothers in poor conditions produced larger (presumably better provisioned) eggs and better quality offspring that show greater survivorship (Lynch & Ennis 1983; Gliwicz & Guisande 1992; Cleuvers et al. 1997; Boersma et al. 1999). This maternal effect on general offspring quality is considered an adaptive reproductive strategy (Roff 1992; Bernardo 1996; Mousseau & Fox 1998) and is seen in various species from flies (Prasad et al. 2003) to fish (Reznick et al. 1996). Daphnia have short generation times and offspring are likely to find themselves in an environment similar to their mothers. Therefore, it can be in the interest of mothers in a poor environment to increase per-offspring investment so that the few offspring she does produce will have a greater chance of survival (e.g. Roff 1992; Bernardo 1996; Rossiter 1996; Cleuvers et al. 1997; Boersma et al. 1999). Our results show for the first time that this pattern also extends to susceptibility to parasites. Further studies are required to elucidate the mechanism and whether it is a side effect of differential offspring quality or whether mothers are anticipating higher liability or encounter with disease in denser populations. For instance, phenotypic plasticity for the size of the Daphnia filter screen might affect encounter rates with P. ramosa—offspring of mothers at low food have larger filter screens with finer mesh size that have a higher probability of collecting bacteria (Lampert 1994).

The implication of the maternal juvenile×adult environment interaction is that females are attempting to provision offspring for the least optimal conditions that could occur in a variable environment. However, females who have spent their whole lives in poor conditions may have insufficient resources to provision offspring as well as mothers that had developed in good conditions before experiencing stress. Similar maternal effects in Daphnia are evident for investment in sexual resting eggs, with large differences between the maternal and offspring environments being a strong determinant of resting egg production by the offspring (Alekseev & Lampert 2001).

We note that density dependent prophylaxis to parasites has been observed in insects (e.g. Reeson et al. 1998), although to our knowledge, never before as a maternal effect. The density effects observed in this experiment were due to maternal crowding, with reduced susceptibility to parasites probably a side effect of the maternal provisioning strategy towards expected low-food levels. High densities often produce the same response as low-food conditions for maternal reproductive investment in Daphnia (Gliwicz & Guisande 1992; Cleuvers et al. 1997; Boersma et al. 1999). As high population densities often precede low-food conditions (Lampert 1991; Mitchell 1997) and both result in exploitation competition (Matveev 1983; Mitchell & Carvalho 2002), maternal response to high density is considered adaptive towards the low-food conditions their offspring are likely to experience (Cleuvers et al. 1997).

We found transgenerational transfer of acquired protection, as has been found previously in invertebrates (e.g. Huang & Song 1999; Little et al. 2003). In the study by Little et al. (2003), infected Daphnia females were cured with antibiotics in order to collect offspring. However, in our experiment, mothers exposed to the parasites only produced offspring if they did not get infected, since infected mothers were sterile by the time the experimental generation were produced from the fourth broods. In previous studies (Mitchell et al. 2005) and in the offspring generation in this study, females that finally showed infection were sterile from about the second or third brood. Future studies will be needed to investigate whether females that were exposed to parasites but remain uninfected have developed immunological molecules that can be passed onto offspring.

We found that maternal exposure to parasites affected offspring susceptibility in a complex three-way interaction involving both host genotype and offspring food levels (figure 3). At low offspring food conditions, infection rates were similar for both clones irrespective of maternal exposure to parasites. However, at high offspring food conditions, one clone (85) was significantly less susceptible only when mothers had encountered parasites, reversing the usual ranking in previous experiments (see §2) and among the controls in this experiment, where clone 85 was more susceptible than 25 (mean±s.e. infection rates 0.75±0.04 and 0.66±0.04, respectively). This is a good example of genetic variation for phenotypic plasticity which often results in unpredictable condition-dependent outcomes (Via 1987; Mousseau & Fox 1998; Schlichting & Pigliucci 1998; Bateson et al. 2004) particularly from maternal indirect genetic effects (Kirkpatrick & Lande 1989; Mousseau & Fox 1998; Wolf et al. 1998). There is often assumed to be a direct relationship between host genotype and resistance phenotype, but this complex genetic interaction will further contribute to context-dependent parasite susceptibility (Stacey et al. 2003; Mitchell et al. 2005). This will weaken the evolutionary response to parasite-mediated selection and could contribute towards the lack of evidence for parasite-mediated selection in wild Daphnia populations in response to Pasteuria infections (Little 2002; Mitchell et al. 2004).

For logistical reasons, we had just two clones in this experiment, but we note that that these two clones differed in their maternal responses to parasite exposure, with only one of the two responding with better protected offspring, and that the genetic component depended on both maternal and offspring environments. Clonal variation and G×E interactions have been found previously for parasite infection rates in this and other species (e.g. Stacey et al. 2003; Mitchell et al. 2004, 2005), although this is the first time maternal effects have been investigated. The clones we used in this experiment showed intermediate levels of susceptibility in previous experiments (see §2), so that there is no reason to consider that the maternal G×E effects discovered for just two clones in this experiment are atypical; indeed, a study based on just two clones likely underestimates the true extent of the phenomenon. It is not unusual for clones to respond in different directions to environmental variation (e.g. Via 1987; Mitchell & Lampert 2000; Mitchell et al. 2005) or for effects to be detected only under certain offspring environments (e.g. Bernardo 1996; Mitchell 1997; Giebelhausen & Lampert 2001).

Our results have implications for population dynamics, the maintenance of genetic polymorphism and for the strength of parasite-mediated selection on traits such as secondary sexual characters and sexual reproduction (Anderson & May 1991; Rossiter 1996; White & Wilson 1999; Beckerman et al. 2002; Little 2002; Woolhouse et al. 2002; Bateson et al. 2004). This is because maternal allocation decisions, maternal environmental effects and indirect genetic effects result in lag times due to delayed life history effects (Rossiter 1996; Beckerman et al. 2002) and can lead to unexpected evolutionary outcomes (Kirkpatrick & Lande 1989; Mousseau & Fox 1998; Wolf et al. 1998). Density dependent changes in host disease resistance alter the stability of the host–pathogen interaction (White & Wilson 1999) and a fundamental assumption in the study of host–parasite interactions is that greater host densities provide increased opportunities for parasite transmission (Anderson & May 1991). The maternal effects of increasing resistance in the face of deteriorating environmental conditions which we report here would act to mitigate or even reverse this effect, thus altering epidemiological processes, and hence population and evolutionary dynamics. This impact would be strengthened if offspring quality–number trade-offs were operating. Because of the scale of these experiments, we were unable to determine brood or offspring sizes beyond noting broods as large or small and presence of sexual eggs, but offspring size–number trade-offs have been previously demonstrated in Daphnia (e.g. Guinnee et al. 2004). If mothers produce more resistant offspring by producing fewer of them, transmission opportunities will be further reduced.

Maternal effects are often considered something to ignore or control for, particularly in experiments designed to elucidate genetic effects. It is quite possible that genetic factors revealed by such studies may be relatively unimportant in the field where maternal conditions are variable, so that context-dependent resistance could dominate (Mitchell et al. 2005). General effects of maternal provisioning (Roff 1992; Bernardo 1996; Rossiter 1996) are rarely linked to offspring resistance to parasites, but could be particularly relevant to the effectiveness of an innate immune system (Møller et al. 1998). A key message from this study is that maternal effects can be extremely large; offspring infection rates were impacted by variation in the maternal environment to a far greater extent than they were by variation in current environments or by clone differences. This surprisingly strong impact on disease outcomes begs the study of maternal condition and resource allocation in crop pests or vectors of human disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Watt and F. Burgess for technical assistance, T. Little and E. Cunningham for discussion and anonymous referees for comments. This work was funded by Natural Environment Research Council.

Footnotes

As this paper exceeds the maximum length normally permitted, the authors have agreed to contribute to production costs.

References

- Agrawal A.A, Laforsch C, Tollrian R. Transgenerational induction of defences in animals and plants. Nature. 1999;401:60–63. 10.1038/43425 [Google Scholar]

- Alekseev V.R, Lampert W. Maternal control of resting-egg production in Daphnia. Nature. 2001;414:899–901. doi: 10.1038/414899a. 10.1038/414899a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson R.M, May R.M. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1991. Infectious diseases of humans: dynamics and control. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson P, et al. Developmental plasticity and human health. Nature. 2004;430:419–421. doi: 10.1038/nature02725. 10.1038/nature02725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckerman A, Benton T.G, Ranta E, Kaitala V, Lundberg P. Population dynamic consequences of delayed life-history effects. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002;17:263–269. 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)02469-2 [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo J. Maternal effects in animal ecology. Am. Zool. 1996;36:83–105. [Google Scholar]

- Boersma M, De Meester L, Spaak P. Environmental stress and local adaptation in Daphnia magna. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1999;44:393–402. [Google Scholar]

- Cleuvers M, Goser B, Ratte H.T. Life history strategy shift by intraspecific interaction in Daphnia magna: change in reproduction from quantity to quality. Oecologia. 1997;110:337–345. doi: 10.1007/s004420050167. 10.1007/s004420050167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham E.J.A, Russell A.F. Egg investment is influenced by male attractiveness in the mallard. Nature. 2000;404:74–77. doi: 10.1038/35003565. 10.1038/35003565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giebelhausen B, Lampert W. Temperature reaction norms of Daphnia magna: the effect of food concentration. Freshwater Biol. 2001;46:281–289. 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2001.00630.x [Google Scholar]

- Gliwicz Z.M, Guisande C. Family planning in Daphnia: resistance to starvation in offspring born to mothers grown at different food levels. Oecologia. 1992;91:2979–2982. doi: 10.1007/BF00650317. 10.1007/BF00650317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grindstaff J.L, Brodie E.D, Ketterson E.D. Immune function across generations: integrating mechanism and evolutionary process in maternal antibody transmission. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2003;270:2309–2319. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2003.2485. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guinnee M.A, West S.A, Little T.J. Testing small clutch size models with Daphnia. Am. Nat. 2004;163:880–887. doi: 10.1086/386553. 10.1086/386553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.C, Song Y.L. Maternal transmission of immunity to white spot syndrome associated virus (WSSV) in shrimp (Penaeus monodon) Dev. Comp. Immunol. 1999;23:545–552. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(99)00038-5. 10.1016/S0145-305X(99)00038-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick M, Lande R. The evolution of maternal characters. Evolution. 1989;43:485–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampert W. The dynamics of Daphnia magna in a shallow lake. Verh. Int. Verein. Limnol. 1991;24:795–798. [Google Scholar]

- Lampert W. Phenotypic plasticity of the filter screens in Daphnia: adaptation to a low-food environment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 1994;39:997–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Little T.J. The evolutionary significance of parasitism: do parasite-driven genetic dynamics occur ex silico? J. Evol. Biol. 2002;15:1–9. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00366.x [Google Scholar]

- Little T.J, O'Connor B, Colegrave N, Watt K, Read A.F. Maternal transfer of strain-specific immunity in an invertebrate. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:489–492. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00163-5. 10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00163-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M, Ennis R. Resource availability, maternal effects and longevity. Exp. Gerontol. 1983;18:147–165. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(83)90008-6. 10.1016/0531-5565(83)90008-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matveev V. Estimating competition in cladocerans using data on dynamics of clutch size and population density. Int. Revue ges. Hydrobiol. 1983;68:785–798. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, S. E. 1997 Clonal diversity and coexistence in Daphnia magna populations. Ph.D. thesis, University of Hull.

- Mitchell S.E, Carvalho G.R. Comparative demographic impacts of ‘info-chemicals’ and exploitative competition: an empirical test using Daphnia magna. Freshwater Biol. 2002;47:459–471. 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2002.00816.x [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S.E, Lampert W. Temperature adaptation in a geographically widespread zooplankter, Daphnia magna. J. Evol. Biol. 2000;13:371–382. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2000.00193.x [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S.E, Read A.F, Little T.J. The effect of a pathogen epidemic on the genetic structure and reproductive strategy of the crustacean, Daphnia magna. Ecol. Lett. 2004;7:848–858. 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00639.x [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell S.E, Rogers E.S, Little T.J, Read A.F. Host–parasite and genotype by environment interactions: temperature modifies potential for selection by a sterilising pathogen. Evolution. 2005;59:70–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller A.P, Christe P, Erritzoe J, Meller A.P. Condition, disease and immune defence. Oikos. 1998;83:301–306. [Google Scholar]

- Mousseau T.A, Fox C.W, editors. Maternal effects as adaptations. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Prasad N.G, Shakarad M, Rajamani M, Joshi A. Interaction between the effects of maternal and larval levels of nutrition on pre-adult survival in Drosophila melanogaster. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2003;5:903–911. [Google Scholar]

- Reeson A.F, Wilson K, Gunn A, Hails R.S, Goulson D. Baculovirus resistance in the Noctuid Spodoptera exempta is phenotypically plastic and responds to population density. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1998;265:1787–1791. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0503 [Google Scholar]

- Reznick D, Callahan H, Llauredo R. Maternal effects on offspring quality in poeciliid fishes. Am. Zool. 1996;36:147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Roff D.A. Chapman & Hall; London: 1992. The evolution of life histories. Theory and analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Roitt I.M. Blackwell Science; Oxford, UK: 1997. Essential immunology. [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter M.C. Incidence and consequences of inherited environmental effects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1996;27:451–476. 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.27.1.451 [Google Scholar]

- Schlichting C.D, Pigliucci M. Sinauer Associates, Inc; Sunderland, MA: 1998. Phenotypic evolution: a reaction norm perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Stacey D.A, Thomas M.B, Blanford S, Pell J.K, Pugh C, Fellowes M.D.E. Genotype and temperature influence pea aphid resistance to a fungal entomopathogen. Physiol. Entomol. 2003;28:75–81. 10.1046/j.1365-3032.2003.00309.x [Google Scholar]

- Via S. Genetic constraints on the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. In: Loeschcke V, editor. Genetic constraints on adaptive evolution. Springer; Berlin: 1987. pp. 47–71. [Google Scholar]

- White K.A.J, Wilson K. Modelling density-dependent resistance in insect–pathogen interactions. Theor. Popul. Biol. 1999;56:163–181. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.1999.1425. 10.1006/tpbi.1999.1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J.B, Brodie E.D, Cheverud J.M, Moore A.J, Wade M.J. Evolutionary consequences of indirect genetic effects. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1998;13:64–69. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(97)01233-0. 10.1016/S0169-5347(97)01233-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolhouse M.E, Webster J.P, Domingo E, Charlesworth B, Levin B.R. Biological and biomedical implications of the co-evolution of pathogens and their hosts. Nat. Genet. 2002;32:569–577. doi: 10.1038/ng1202-569. 10.1038/ng1202-569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]