Abstract

Mutualisms can be viewed as biological markets in which partners of different species exchange goods and services to their mutual benefit. Trade between partners with conflicting interests requires mechanisms to prevent exploitation. Partner choice theory proposes that individuals might foil exploiters by preferentially directing benefits to cooperative partners. Here, we test this theory in a wild legume–rhizobium symbiosis.

Rhizobial bacteria inhabit legume root nodules and convert atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) to a plant available form in exchange for photosynthates. Biological market theory suits this interaction because individual plants exchange resources with multiple rhizobia. Several authors have argued that microbial cooperation could be maintained if plants preferentially allocated resources to nodules harbouring cooperative rhizobial strains. It is well known that crop legumes nodulate non-fixing rhizobia, but allocate few resources to those nodules. However, this hypothesis has not been tested in wild legumes which encounter partners exhibiting natural, continuous variation in symbiotic benefit.

Our greenhouse experiment with a wild legume, Lupinus arboreus, showed that although plants frequently hosted less cooperative strains, the nodules occupied by these strains were smaller. Our survey of wild-grown plants showed that larger nodules house more Bradyrhizobia, indicating that plants may prevent the spread of exploitation by favouring better cooperators.

Keywords: exploitation, cooperation, symbiosis, mutualism, nitrogen fixation, sanctions

1. Introduction

Mutualisms can be modelled as biological markets in which members of each species exchange resources or services (Noë & Hammerstein 1994). However, markets are vulnerable to exploitation and require mechanisms to promote fair commodity exchange (Bronstein 2001). Both ‘partner choice’ and ‘partner fidelity’ can constrain exploitation (Bull & Rice 1991; Noë et al. 1991; Simms & Taylor 2002; Sachs et al. 2004). Partner fidelity occurs when individuals receive returned benefits from their investments in others. Such fitness feedbacks can arise from vertical transmission of symbionts (Fine 1975; Axelrod & Hamilton 1981), certain spatial structures (Wilkinson 1997; Doebeli & Knowlton 1998), or other mechanisms that assure long-term reciprocal interactions. However, positive fitness feedback can be weakened by horizontal transmission and/or competition among potential mutualists (Soberon 1985; Frank 1994, 1996a,b; West et al. 2002a,b; Bronstein et al. 2003; Wilson et al. 2003). In such cases, exploitation may be constrained by partner choice, in which individuals preferentially extend benefits to cooperative members of the partner species (Bull & Rice 1991; Simms & Taylor 2002; Sachs et al. 2004). There are few empirical tests of the partner choice hypothesis (but see Bshary & Grutter 2002; Grutter & Bshary 2003; Kiers et al. 2003; Mueller et al. 2004).

Root-nodule inhabiting bacteria (hereafter termed rhizobia) are particularly attractive model systems for examining the maintenance of mutualism (Denison 2000; Simms & Taylor 2002). Rhizobia fix atmospheric nitrogen in exchange for photosynthates, but the interaction does not always appear cooperative. Plant and bacteria reproduce and disperse independently (Simms & Taylor 2002) and individual plants usually interact with multiple bacterial genotypes that vary from beneficial to completely ineffective mutualists (Moawad & Beck 1991; Quigley et al. 1997; Moawad et al. 1998; Denison 2000; Thrall et al. 2000). Several authors have suggested that rhizobial cooperation could be promoted by plant traits that preferentially allocate resources to nodules harbouring cooperative strains (Denison 2000; Simms & Taylor 2002; West et al. 2002b; Sprent 2003). Further, crop legumes are known to sanction (Denison 2000) nodules occupied by ineffective rhizobia (Chen & Thornton 1940; Wadisirisuk & Weaver 1985; Kiers et al. 2003). However, the partner choice hypothesis has not been tested in wild legumes interacting with their naturally occurring rhizobia.

Here, we use a greenhouse experiment to test whether yellow bush lupin, Lupinus arboreus Sims, a short-lived perennial shrub in the Leguminosae, can allocate resources to more effective symbionts when nodulated by mixed populations of bacterial strains with which they naturally occur.

2. Material and Methods

Yellow bush lupin is native to the central California coast and is common throughout Bodega Marine Reserve (BMR; 38°19′01″ N, 123°04′18″ W). At BMR, L. arboreus can occur alone or with up to four other lupin species: Lupinus nanus, Lupinus bicolor, Lupinus variicolor and Lupinus chamissonis (Barbour et al. 1973). Like other lupins (Bottomley et al. 1994; Ludwig et al. 1995; Barrera et al. 1997; but see Stepkowski et al. 2003), lupins at BMR associate predominantly with Bradyrhizobium strains that are closely related to the primary soyabean symbiont, Bradyrhizobium japonicum, and are generally designated as Bradyrhizobium sp. (Lupinus) (Taylor & Simms, unpublished data).

Rhizobia fix nitrogen only after differentiating into bacteroids within the plant (Simms & Bever 1998). Although there is debate about the ability of bacteroids to survive nodule senescence, de-differentiate and reproduce, Bradyrhizobium bacteroids or vegetative cells of the strain generating bacteriods apparently survive senescence of lupin nodules (Sprent et al. 1987). Mycorrhizae are unlikely to be important for the nutrient or water relations of lupins (Trinick 1977; Avio et al. 1990; Oba et al. 2001).

Seeds and bacteria were collected from six intensively studied sites at BMR (Maron & Simms 2001), three in dunes and three in grasslands, located ca 500 m apart. Seeds were collected from two maternal plants sampled from each of three sites: South Grassland, Mid Grassland and Mid Dunes. Ten bacterial isolates were obtained from nodules excised from two naturally occurring lupins at each of five sites: South Grassland, Mid Grassland, South Dunes, Mid Dunes and Mussel Point.

We genotyped bacterial isolates using PCR-RFLPs of the 16S–23S rRNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region (Taylor & Simms, unpublished data) and characterized their symbiotic benefit to two lupin species, L. arboreus and L. variicolor (J. Povich and E. L. Simms, unpublished data). Three strains were selected that differed in RFLP type and represented the observed range of symbiotic benefit to L. arboreus (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Bradyrhizobium strains.

| strain | wild hosta | location | shoot mass (g)b | ranked symbiotic benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA11-1 | L. arboreus | South Grassland | 1.93 | poor |

| LA17-1 | L. arboreus | North Dunes | 2.14 | mediocre |

| LB16-1 | L. bicolor | Mussel Point | 2.36 | good |

Host from which strain was isolated.

Average aboveground dry mass after 20 weeks of 48 L. arboreus plants inoculated with the strain. Strains differed significantly (F2,126=12.46, p≤0.0001); experiment-wide 95% confidence limit=0.12 g.

To test whether plants preferentially allocate resources to more beneficial bacteria, we established three mixed inoculation treatments (mediocre and poor), (good and poor), (good and mediocre) and an uninoculated control treatment. Each treatment was applied to one randomly assigned seedling from each of six maternal plants in each of five blocks. Within a block, the six seedlings in an inoculation treatment were each grown in a separate pot, with pots racked together to form a subplot within a fully randomized split plot design. We maintained 1 m distances among racks to prevent cross-contamination. Four racks comprised a block. Plants were assigned to blocks by size, which primarily reflected germination date. Blocks varied by plant age, location on the greenhouse bench, inoculation volume and harvest date.

On 25 July 2003, seeds for blocks 1–3 were scarified and surface-sterilized by soaking in concentrated sulphuric acid for 15 min and rinsing in sterile deionized water. The seeds were germinated in autoclaved trays of moist vermiculite under metal halide lamps set to a 23 h photoperiod at room temperature. After 12 days, seedlings were transplanted to sterile Deepots (Steuwe & Sons) filled with autoclaved calcine-clay (Turface, Profile Products). On 6 August 2003, seeds for blocks 4 and 5 were surface-sterilized for 20 min in bleach, rinsed in sterile water and nick scarified with a razorblade. After imbibing sterile water for 3 days, germinated seeds were planted directly into sterile Deepots of autoclaved Turface. All seedlings were watered four times per day with UV-sterilized carbon-filtered tap water until 20 August 2003, after which they were watered as necessary (usually daily) and fertilized biweekly with nitrogen-free modified Jensen's solution.

Each strain was initiated from a single-plated colony grown in liquid culture (modified arabinose-gluconate (MAG) media, modified by P. van Berkum from Cole & Elkan 1973) and cryopreserved in 60% glycerol. Inoculant was prepared by regrowing on solid media and washing cells with sterile 0.85 M KCl. Cell densities were determined by absorbance and adjusted to 1×108 cells ml−1. Cell numbers were calibrated by cytometer and confirmed with plate counts. Mixed inoculants were prepared by combining equal quantities of the two appropriate single-strain inoculants. We pipetted 10 ml of mixed inoculant onto each seedling in blocks 1–3 on 12 August 2003. On 1 September 2003, we inoculated seedlings in blocks 4 and 5 with 7 ml. Control plants within a block received the appropriate volume of sterile 0.85 M KCl.

Block 1 was harvested on 21 September 2003; remaining plants were harvested on 6–7 January 2004. During both harvests, we selected a range of nodule sizes from each plant. To ensure that small nodules were not younger than large nodules, we chose small nodules proximal along the roots from which large nodules were obtained. We measured the diameters of six nodules, then each was excised, surface-sterilized with household bleach and stored at −20 °C in 5× its volume of 20% Chelex 100 resin (Sigma Chemical) in 2× PCR buffer (40 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0; 100 mM KCl). Immediately after thawing, nodules were heated and vortexed at 95 °C, centrifuged for 5 min at 16 000g. The resulting crude extract was stored at −20 °C.

From each sample, we amplified 1440 bp of the intergenic spacer between the large and small ribosomal subunits (hereafter referred to as ITS) using primers ITS450 and ITS1440 (van Berkum & Fuhrmann 2000). The 50 μl PCR reaction contained 2.0 mM MgCl, 0.25 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM primers, 1.25 units Taq polymerase (Invitrogen Life Technologies), 1× Invitrogen PCR buffer and 10 μl of diluted nodule extract (usually a 25-fold dilution). Reactions were initiated with a 2 min 95 °C denaturation and ended with a 10 min extension step at 72 °C. Cycling involved 94 °C denaturation for 30 s, 70 °C annealing for 40 s, reduced by 0.5 °C per cycle to 60 °C in the touchdown phase, with an additional 30 cycles at 60 °C, and 72 °C extension for 1.5 min. Aliquots of the PCR product were digested with endonucleases MwoI and HgaI. Fragments were separated on 10 cm gels of 1% regular agarose and 2% high resolution agarose (Sigma Chemical) in tris-acetate-EDTA electrophoresis (TAE) buffer at 170 V for 2–3 h, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized on a UV transilluminator.

Owing to germination problems, each treatment in block 5 lacked one plant. Nineteen plants died during a late August heatwave; five were replaced with substitutes of the same age that had been appropriately inoculated contemporaneously. By harvest, 17 additional plants had died, including nine control plants, reducing the number of harvested plants to 85. Of these, one inoculated plant failed to nodulate and PCR reactions failed on all nodules of three other inoculated plants. Ultimately, we obtained informative nodule occupancy data from 65 plants.

Nodule size and strain identity were analysed with a repeated measures nested analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a compound symmetry covariance structure using the SAS 9.1 mixed procedure (SAS Institute 2004). The model included nodules as repeated measures within plants, plants as random subjects nested within fixed inoculation treatments and treatments nested within random blocks. Plant family structure was too unbalanced to analyse. The block effect and block by plant (treatment) interaction were non-significant and raised the Akaike Information Criterion score, so these effects were dropped. For each inoculation treatment, we subsequently performed a one-way ANOVA of plant effect on nodule size, used the residuals to classify nodules into two or three size classes and used chi-squared tests to determine whether standardized nodule sizes were distributed independently of strain identity.

To establish the relationship between nodule diameter and Bradyrhizobium population size within a nodule, we surveyed six nodules each from nine L. arboreus seedlings at four sites across BMR. Nodules were collected, measured and surface-sterilized as described above. Each nodule was macerated in sterile MAG media and the slurry was serially diluted and plated on MAG-agar plates for colony counts. Plate counts were averaged across at least two replicates per nodule to estimate the Bradyrhizobium population size. Colony number was natural log-transformed to normalize residuals and regressed on nodule diameter using Jmp 5.1.2 (SAS Institute).

3. Results

We obtained readable bands from 301 nodules. Banding patterns from two nodules suggested occupancy by more than one isolate. We found no evidence of cross-contamination among treatments. At harvest, no control plants were nodulated and all identified strains matched at least one of the strains with which their host plant had been inoculated.

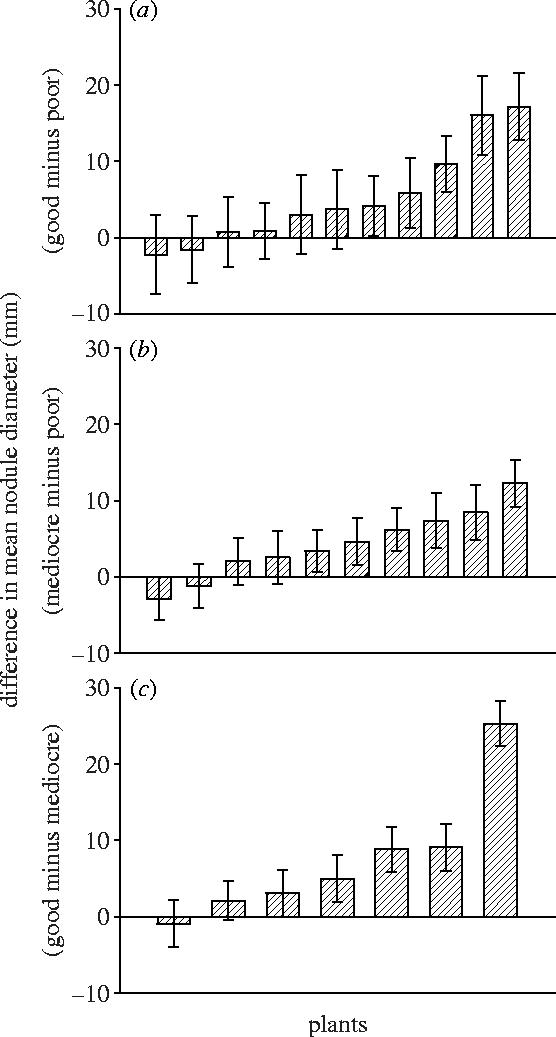

Nodule sizes within plants were significantly influenced by occupant identity (F2,25=16.42, p<0.0001). Within the average plant, nodules that were occupied by the more beneficial strain were significantly larger (figure 1a–c). However, because strain identity interacted significantly with treatment (F1,25=10.14, p<0.004), we also examined the strain effect in each treatment separately.

Figure 1.

Within plant average difference in sizes of nodules occupied by best versus worst strain. Plants inoculated by (a) strains LB16-1 (good) and LA11-1 (poor), (b) strains LA17-1 (mediocre) and LA11-1 (poor), (c) strains LB16-1 (good) and LA17-1 (mediocre). Bars indicate 1 s.e.

Of 24 plants inoculated with both good and poor strains, we detected 11 plants nodulated by both strains. Occupant identity explained a significant component of variation in nodule size within plants (F1,10=5.38, p=0.04), with smaller average size among nodules occupied by the poor strain (figure 1a). Further, contingency table analysis indicated that strain distribution between nodule size categories differed from random, with the poor strain occurring more frequently in smaller nodules (table 2a, χ12=5.00, p<0.03). Of the 14 plants in which we detected only one strain, all were occupied by the poor strain.

Table 2.

Contingency tables of strain identity versus nodule size class after accounting for differences among plants.

| strain | rank | large | small | medium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) strains LB16-1 versus LA11-1 | ||||

| LB16-1 | good | 10 | 8 | |

| LA11-1 | poor | 8 | 25 | |

| , p<0.03 | ||||

| (b) strains LA17-1 versus LA11-1 | ||||

| LA17-1 | meda | 11 | 6 | 12 |

| LA11-1 | poor | 0 | 8 | 18 |

| , p<0.002 | ||||

| (c) strains LB16-1 versus LA17-1 | ||||

| LB16-1 | good | 6 | 2 | |

| LA17-1 | meda | 6 | 17 | |

| , p<0.02 |

med, mediocre.

Of 22 plants inoculated with both mediocre and poor strains, we found 10 nodulated by both strains. Occupant identity explained a significant component of variation in nodule size within plants (F1,9=7.91, p=0.02), with smaller average size among nodules occupied by the poor strain (figure 1b). Strain distribution among nodule size categories differed from random (table 2b, χ22=12.36, p<0.002), with the poor strain occurring more frequently in smaller nodules. Of the 12 plants in which we detected only one strain, three contained the poor and nine contained the mediocre strain.

Finally, of 18 plants inoculated with both good and mediocre strains, seven plants were nodulated by both strains and occupant identity explained a significant component of variation in nodule size within plants (F1,6=10.48, p=0.02), with smaller average size among nodules occupied by the mediocre strain (figure 1c). As in the previous two treatments, strain distribution between nodule size categories differed from random, with the mediocre strain occurring more frequently in smaller nodules (table 2c, χ12=5.99, p<0.02). Of the 11 plants in which we detected only one strain, all were occupied by the mediocre strain.

Among 33 nodules sampled randomly from nine wild-grown L. arboreus seedlings collected at BMR, total population size of Bradyrhizobium cells in a nodule regressed positively on nodule size (r2=0.2, p<0.01).

4. Discussion

In lupins experimentally infected by divergent pairs of naturally occurring Bradyrhizobium strains, nodule size varied with the symbiotic effectiveness of bacterial occupants. On average, nodules inhabited by the less beneficial strain were smaller. In a separate survey of wild-grown L. arboreus, larger nodules contained more Bradyrhizobium cells, as previously found for soyabean nodules (Kiers et al. 2003). These results support the hypothesis that legumes can favour more cooperative rhizobia by manipulating bacterial fitness in the nodule (Denison 2000; Simms & Taylor 2002; West et al. 2002b; Sprent 2003).

Although our experiment does not specifically distinguish between plant or bacterial control of allocation to nodules, we argue that the original hypothesis is more parsimonious. Our data complement the findings of Kiers et al. (2003), who found that the fresh weights of soyabean nodules deprived of atmospheric dinitrogen were smaller than those of unmanipulated nodules occupied by the same strain on the same plant. They suggested that plants might control nodule size in part by altering oxygen supply. Other mechanisms might also contribute to the effect (Simms & Taylor 2002).

Among the 37 plants in which we found only one strain, 25 had been inoculated with a mix including the good strain, yet we detected this strain in none of these plants. This result corroborates other studies, which have shown that the ability of rhizobia to compete for nodulation may be uncorrelated with symbiotic benefit (Triplett & Sadowsky 1992; Vasquez-Arroyo et al. 1998; Bloem & Law 2001; Hafeez et al. 2001).

For nodule-specific plant responses to constrain cheating effectively, individual nodules must be occupied by single bacterial genotypes (Denison 2000; West et al. 2002b; Kiers et al. 2003; Denison & Kiers 2004). Among the 301 nodules from which we obtained readable RFLP bands were two that showed a banding pattern suggestive of occupancy by more than one isolate. These data suggest that multiply infected nodules are rare.

We believe that our study provides the first evidence that nodule size scales with naturally occurring variation in symbiotic effectiveness of the bacterial occupant. Past workers on agricultural legumes have noted that ineffective strains often result in small nodules (Simms & Taylor 2002), but, with a few notable exceptions (Chen & Thornton 1940; Singleton & Stockinger 1983; Kiers et al. 2003), the phenomenon has rarely been quantified.

In summary, our results suggest that post-infection partner choice could be an important mechanism constraining exploitation by rhizobia in this legume–rhizobium mutualism. We look forward to additional tests of the assumptions of this theory.

Acknowledgments

We are most grateful to C. Coleman, M. Horn and T.F. Colton for assistance with harvests and data entry, and to C.T. Hsu and A. Jain, who measured nodules and censused bacterial densities. Major funding was provided by DEB-0108708 and DEB-9996236 to ELS from the USA NSF. Funds were also provided by the Miller Institute for Basic Research, the UC Berkeley Committee on Research and the UC Berkeley Faculty Research Fund for the Biological Sciences. Mona Urbina was supported by GM48983 from the US NIH to D.A. Gailey of CSU East Bay. We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for helping to improve the manuscript. We thank Bodega Marine Reserve for access to field sites, and Reserve Manager P. Conners for his insights and assistance.

Footnotes

Present address: Institute of Arctic Biology, University of Alaska, 311 Irving I Building, 902 N. Koyukuk Drive, Fairbanks, AK 99775-7000, USA.

Present address: Forestry and Forest Products Research Institute, Microbial Ecology Laboratory, 1 Matsunosato, Tsukuba 305-8687, Japan.

References

- Avio L, Sbrana C, Giovannetti M. The response of different species of Lupinus to VAM endophytes. Symbiosis. 1990;9:321–323. [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod R, Hamilton W.D. The evolution of cooperation. Science. 1981;211:1390–1396. doi: 10.1126/science.7466396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour M.G, Craig R.B, Drysdale F.R, Ghiselin M.T. University of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1973. Coastal ecology: Bodega Head; pp. 263–264. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera L.L, Trujillo M.E, Goodfellow M, Garcia F.J, Hernandez-Lucas I, Davila G, van Berkum P, Martinez-Romero E. Biodiversity of bradyrhizobia nodulating Lupinus spp. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 1997;47:1986–1091. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloem J.F, Law I.J. Determination of competitive abilities of Bradyrhizobium japonicum strains in soils from soybean production regions in South Africa. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2001;33:181–189. 10.1007/s003740000303 [Google Scholar]

- Bottomley P.J, Cheng H.-H, Strain S.R. Genetic structure and symbiotic characteristics of a Bradyrhizobium population recovered from a pasture soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994;60:1754–1761. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.6.1754-1761.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein J.L. The exploitation of mutualisms. Ecol. Lett. 2001;4:277–287. 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2001.00218.x [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein J.L, Wilson W.G, Morris W.E. Ecological dynamics of mutualist/antagonist communities. Am. Nat. 2003;162:S24–S39. doi: 10.1086/378645. 10.1086/378645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bshary R, Grutter A.S. Experimental evidence that partner choice is a driving force in the payoff distribution among cooperators or mutualists: the cleaner fish case. Ecol. Lett. 2002;5:130–136. 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00295.x [Google Scholar]

- Bull J.J, Rice W.R. Distinguishing mechanisms for the evolution of cooperation. J. Theor. Biol. 1991;149:63–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(05)80072-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.C, Thornton H.G. The structure of ‘ineffective’ nodules and its influence on nitrogen fixation. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1940;129:208–229. [Google Scholar]

- Cole M.A, Elkan G.H. Transmissible resistance to penicillin-G, neomycin, and chloramphenicol in Rhizobium japonicum. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1973;4:248–253. doi: 10.1128/aac.4.3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison R.F. Legume sanctions and the evolution of symbiotic cooperation by rhizobia. Am. Nat. 2000;156:567–576. doi: 10.1086/316994. 10.1086/316994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denison R.F, Kiers E.T. Why are most rhizobia beneficial to their plant hosts, rather than parasitic? Microbes Infect. 2004;6:1235–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.08.005. 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebeli M, Knowlton N. The evolution of interspecific mutualisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:8676–8680. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8676. 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine P.E.M. Vectors and vertical transmission: an epidemiological perspective. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1975;266:173–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb35099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S.A. Genetics of mutualism: the evolution of altruism between species. J. Theor. Biol. 1994;170:393–400. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1994.1200. 10.1006/jtbi.1994.1200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank S.A. Host control of symbiont transmission: the separation of symbionts into germ and soma. Am. Nat. 1996a;148:1113–1124. 10.1086/285974 [Google Scholar]

- Frank S.A. Host–symbiont conflict over the mixing of symbiotic lineages. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1996b;263:339–344. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grutter A.S, Bshary R. Cleaner wrasse prefer client mucus: support for partner control mechanisms in cleaning interactions. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2003;270:S242–S244. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeez F.Y, Hameed S, Ahmad T, Malik K.A. Competition between effective and less effective strains of Bradyrhizobium spp. for nodulation on Vigna radiata. Biol. Fertil. Soils. 2001;33:382–386. 10.1007/s003740000337 [Google Scholar]

- Kiers E.T, Rousseau R.A, West S.A, Denison R.F. Host sanctions and the legume–rhizobium mutualism. Nature. 2003;425:78–81. doi: 10.1038/nature01931. 10.1038/nature01931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig W, et al. Comparative sequence analysis of 23S rRNA from Proteobacteria. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1995;18:164–188. [Google Scholar]

- Maron J.L, Simms E.L. Rodent-limited establishment of bush lupine: field experiments on the cumulative effect of granivory. J. Ecol. 2001;89:578–588. 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2001.00560.x [Google Scholar]

- Moawad H.A, Beck D.P. Some characteristics of Rhizobium leguminosarum isolates from un-inoculated field-grown lentil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1991;23:933–937. 10.1016/0038-0717(91)90173-H [Google Scholar]

- Moawad H.A, El-Din S.M.S.B, Abdel-Aziz R.A. Improvement of biological nitrogen fixation in Egyptian winter legumes through better management of Rhizobium. Plant Soil. 1998;204:95–106. 10.1023/A:1004335112402 [Google Scholar]

- Mueller U.G, Poulin J, Adams R.M.M. Symbiont choice in a fungus-growing ant (Attini, Formicidae) Behav. Ecol. 2004;15:357–364. 10.1093/beheco/arh020 [Google Scholar]

- Noë R, Hammerstein P. Biological markets: supply and demand determine the effect of partner choice in cooperation, mutualism and mating. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1994;35:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Noë R, Vanschaik C.P, Vanhooff J. The market effect—an explanation for pay-off asymmetries among collaborating animals. Ethology. 1991;87:97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Oba H, Tawaraya K, Wagatsuma T. Arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization in Lupinus and related genera. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2001;47:685–694. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley P.E, Cunningham P.J, Hannah M, Ward G.N, Morgan T. Symbiotic effectiveness of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii collected from pastures in south-western Victoria. Aust. J. Exp. Agric. 1997;37:623–630. 10.1071/EA96089 [Google Scholar]

- Sachs J.L, Mueller U.G, Wilcox T.P, Bull J.J. The evolution of cooperation. Q. Rev. Biol. 2004;79:135–160. doi: 10.1086/383541. 10.1086/383541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute, Inc. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 2004. SAS/STAT 9.1 User's guide; pp. 2659–2851. [Google Scholar]

- Simms E.L, Bever J.D. Evolutionary dynamics of rhizopine within spatially structured rhizobium populations. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1998;265:1713–1719. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0493 [Google Scholar]

- Simms E.L, Taylor D.L. Partner choice in nitrogen-fixation mutualisms of legumes and rhizobia. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2002;42:369–380. doi: 10.1093/icb/42.2.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton P.W, Stockinger K.R. Compensation against ineffective nodulation in soybean. Crop Sci. 1983;23:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Soberon J.M. Cheating and taking advantage in mutualistic interactions. In: Boucher D.H, editor. The biology of mutualism. Croom Helm; London: 1985. pp. 192–216. [Google Scholar]

- Sprent J. Plant biology—mutual sanctions. Nature. 2003;422:672–674. doi: 10.1038/422672a. 10.1038/422672a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprent J.I, Sutherland J.M, Faria S.M.d. Some aspects of the biology of nitrogen-fixing organisms. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 1987;317:111–129. [Google Scholar]

- Stepkowski T, Swiderska A, Miedzinska K, Czaplinska M, Swiderski M, Biesiadka J, Legocki A.B. Low sequence similarity and gene content of symbiotic clusters of Bradyrhizobium sp. WM9 (Lupinus) indicate early divergence of ‘lupin’ lineage in the genus Bradyrhizobium. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;84:115–124. doi: 10.1023/a:1025480418721. 10.1023/A:1025480418721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thrall P.H, Burdon J.J, Woods M.J. Variation in the effectiveness of symbiotic associations between native rhizobia and temperate Australian legumes: interactions within and between genera. J. Appl. Ecol. 2000;37:52–65. 10.1046/j.1365-2664.2000.00470.x [Google Scholar]

- Trinick M.J. Vesicular-arbuscular infection and soil phosphorus utilization in Lupinus spp. New Phytol. 1977;78:297–304. [Google Scholar]

- Triplett E.W, Sadowsky M.J. Genetics of competition for nodulation of legumes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1992;46:399–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002151. 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berkum P, Fuhrmann J.J. Evolutionary relationships among the soybean bradyrhizobia reconstructed from 16S rRNA gene and internally transcribed spacer region sequence divergence. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000;50:2165–2172. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-6-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez-Arroyo J, Sessitsch A, Martinez E, Peña-Cabriales J.J. Nitrogen fixation and nodule occupancy by native strains of Rhizobium on different cultivars of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Plant Soil. 1998;204:147–154. 10.1023/A:1004399531966 [Google Scholar]

- Wadisirisuk P, Weaver R.W. Importance of bacteroid number in nodules and effective nodule mass to dinitrogen fixation by cowpeas. Plant Soil. 1985;87:223–231. [Google Scholar]

- West S.A, Kiers E.T, Pen I, Denison R.F. Sanctions and mutualism stability: when should less beneficial mutualists be tolerated? J. Evol. Biol. 2002a;15:830–837. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2002.00441.x [Google Scholar]

- West S.A, Kiers E.T, Simms E.L, Denison R.F. Nitrogen fixation and the stability of the legume–rhizobium mutualism. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2002b;269:685–694. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1878 [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson D.M. The role of seed dispersal in the evolution of mycorrhizae. Oikos. 1997;78:394–396. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W.G, Morris W.F, Bronstein J.L. Coexistence of mutualists and exploiters on spatial landscapes. Ecol. Monogr. 2003;73:397–413. [Google Scholar]