Abstract

Although the phylogeny of centipedes has found ample agreement based on morphology, recent analyses incorporating molecular data show major conflict at resolving the deepest nodes in the centipede tree. While some genes support the classical (morphological) hypothesis, others suggest an alternative tree in which the relictual order Craterostigmomorpha, restricted to Tasmania and New Zealand, is resolved as the sister group to all other centipedes. We combined all available data including seven genes (totalling more than 8 kb of genetic information) and 153 morphological characters for 24 centipedes, and conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate where the conflict resides. Our data showed that the classical hypothesis is obtained primarily when nuclear ribosomal genes exert dominance in the character data matrix (at high gap costs), while the alternative tree is obtained when protein-encoding genes account for most of the cladogram length (at low gap costs). In this particular case, the addition of genetic data does not produce a more stable hypothesis for deep centipede relationships than when analysing certain genes independently, but the overall conflict in the data can be clearly detected via a sensitivity analysis, and support and stability of shallow nodes increase as data are added.

Keywords: Chilopoda, Myriapoda, molecular data, sensitivity analysis, iterative pass optimization

1. Introduction

Among the higher arthropod groups, perhaps the best-resolved phylogeny is that of Chilopoda: the centipedes. With five orders—Scutigeromorpha, Lithobiomorpha, Craterostigmomorpha, Scolopendromorpha, and Geophilomorpha—almost all published phylogenies based on morphology, molecules, or combined morphological and molecular evidence conclude that (i) Chilopoda is monophyletic, (ii) each of the five centipede orders is monophyletic, and (iii) the Scutigeromorpha (=Notostigmophora: centipedes with dorsal spiracles) are the sister group to all other centipedes (=Pleurostigmophora: centipedes with pleural spiracles) (Borucki 1996; Edgecombe et al. 1999; Giribet et al. 1999; Edgecombe & Giribet 2002, 2004). Furthermore, relationships within Pleurostigmophora are well established, with Lithobiomorpha as sister group to the remaining orders (grouped as the Phylactometria) and with the two orders with epimorphic development (Scolopendromorpha and Geophilomorpha) forming a clade, as resolved in classical morphological studies (Verhoeff 1902–1925; Fahlander 1938; Dohle 1985; see figure 1). Only one recent morphological study has suggested an alternative hypothesis, by re-rooting the centipede tree between Geophilomorpha and Scolopendromorpha (Ax 1999). That hypothesis was defended using only a subset of the characters included in more completely sampled studies, and is less parsimonious than the Notostigmophora–Pleurostigmophora split (Kraus 2001; Edgecombe & Giribet 2002). Molecular analyses using nuclear ribosomal genes yield results that are highly congruent with the morphology-based hypothesis (Edgecombe et al. 1999; Giribet et al. 1999; Edgecombe & Giribet 2002, 2004), whereas some nuclear protein-coding genes have produced phylogenetic hypotheses that conflict with the nuclear ribosomal genes as well as with morphology (Shultz & Regier 1997; Regier & Shultz 2001b; Regier et al. 2005).

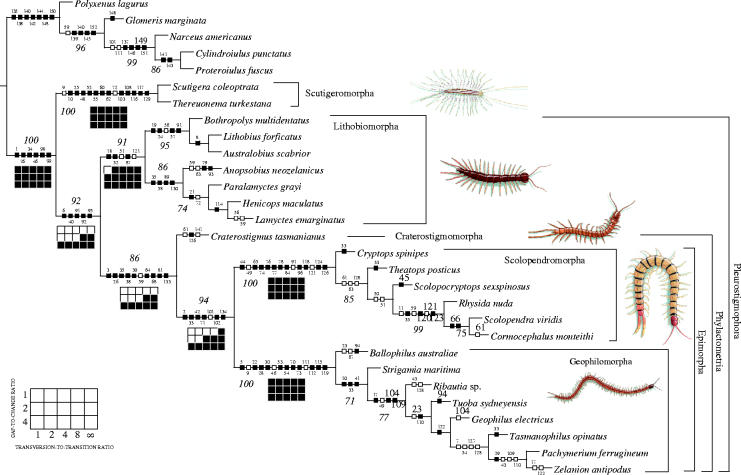

Figure 1.

Cladogram derived from parsimony analysis of the morphological dataset using a heuristic search with 1000 replicates of random addition sequence followed by TBR branch swapping, with character optimizations (boxes with small numbers) and jackknife frequencies greater than 70% (larger italic numbers). A second equally parsimonious cladogram inverts the placement of Ribautia and Geophilus. Character optimizations are represented by squares; solid squares indicate unique changes, open squares indicate homoplastic characters. Navajo rugs represent the sensitivity analysis for the combined analysis of all molecules and morphology for 15 analytical parameters (see parameter legend for Navajo rug in the lower left corner; black squares indicate monophyly, open squares represent non-monophyly). Centipede icons by Barbara Duperron.

Elucidating the deep history of Chilopoda forces us to confront ordinal divergences that date to the Palaeozoic. Fossils date the crown group of Chilopoda to at least the Upper Silurian (ca 418 million years ago). Scutigeromorpha is known from the Upper Silurian–Middle Devonian taxon Crussolum (Shear et al. 1998; Anderson & Trewin 2003). The Middle Devonian Devonobius Shear & Bonamo 1988, is universally identified as a member of Phylactometria, the clade that unites Craterotigmomorpha, Scolopendromorpha and Geophilomorpha (Shear & Bonamo 1988; Borucki 1996; Edgecombe & Giribet 2004). In the context of the widely endorsed cladogram, Devonobius dates the split of Lithobiomorpha from Phylactometria to at least the Middle Devonian. The epimorphic orders Scolopendromorpha and Geophilomorpha have their earliest records in the Upper Carboniferous (Mundel 1979) and Upper Jurassic (Schweigert & Dietl 1997), respectively.

Given the amount of morphological data bearing on centipede phylogeny and the existence of several molecular analyses employing different genes, the time is ripe for a synthesis of the available data. The aim of this paper is to combine all the evidence published for the phylogeny of centipedes to produce a robust phylogeny of the group beyond the use of preferred gene fragments or sets of characters, as well as to identify potential sources of conflict between datasets. Therefore we combine a refined version of our morphological dataset (Edgecombe & Giribet 2004) with our own data on two nuclear ribosomal genes and two mitochondrial genes, together with the data on three nuclear protein-coding genes published by Regier and collaborators (Regier et al. 2005). This represents ca 8 kb of molecular data per taxon and 153 morphological characters—a substantial increase in the character sample compared to previous analyses. The data are analysed independently and in combination using dynamic homology under the parsimony criterion implemented in POY.

2. Material and methods

(a) Taxa

In order to maximize the amount of available sequence data per taxon we selected 24 centipede taxa (2 Scutigeromorpha, 7 Lithobiomorpha, 1 Craterostigmomorpha, 6 Scolopendromorpha, and 8 Geophilomorpha) and 5 millipede taxa as outgroups (table 1). Species were chosen as terminals except in a few cases where two species of the same genus were combined to maximize the amount of available genetic data (Polyxenus, Thereuonema, Cryptops, Strigamia and Geophilus). In these instances, the morphological codings have been adjusted to the species represented in our morphological datasets (figure 1), and generic designations are used for the molecular and total evidence analyses (figure 2).

Table 1.

Chilopod and diplopod taxonomic and sequence data with GenBank accession codes. Dashes indicate an interval of GenBank accession numbers (e.g. AY310225-7 includes accession numbers AY310225, AY310226, and AY310227).

| 18S rRNA | 28S rRNA | 16S rRNA | COI | EF1a | EF2 | POL II | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diplopoda | ||||||||

| Polyxenida: Polyxenidae | Polyxenus fasciculatus | AF173235 | AF173267 | AF370840 | U90055 | AF240826 | AF139001–2 | |

| Glomerida: Glomeridae | Glomeris marginata | AY288685 | AF005467 | AF240795 | AY310257 | AF240912–4 | ||

| Julida: Blaniulidae | Proteroiulus fuscus | AF173236 | AF370804 | AF370866 | AF370842 | AF063415 | AY310277 | AF139000, AF240941–2 |

| Julida: Julidae | Cylindroiulus punctatus | AF005448 | AF005463 | AF240792 | AY310252 | AF240904–6 | ||

| Spirobolida: Spirobolidae | Narceus americanus | AY288686 | AF370805 | AF370867 | AF370843 | U90053 | AY310269 | U90039, AF240927 |

| Chilopoda | ||||||||

| Scutigeromorpha | ||||||||

| Scutigeridae | Scutigera coleoptrata | AF173238 | AF173269 | AF370859 | DQ201426 | U90057 | AY310285 | U90042, AF240951 |

| Thereuonema turkestana/T. sp. | DQ201417 | DQ201420 | DQ201423 | DQ201427 | AY305478 | AY305523 | AY305619–21 | |

| Lithobiomorpha | ||||||||

| Lithobiidae | Lithobius forficatus | X90653-4 | X90656 | AF373608 | AJ270997 | AF240799 | AY310267 | AY310209–11 |

| Australobius scabrior | AF173241 | AF173272 | DQ201424 | DQ201428 | AY310166 | AY310246 | AY310184–6 | |

| Bothropolys multidentatus | AF334272 | AF334293 | AF334334 | AF240789 | AY305492 | AF240896–8 | ||

| Henicopidae | Anopsobius neozelanicus | AF173248 | AF173274 | AF334337 | AF334313 | AY305459 | AY305489 | AY305537–40 |

| Henicops maculatus | DQ201418 | AF173275 | AF334340 | AF334316 | AY310171 | AY310260-1 | AY310199–201 | |

| Lamyctes emarginatus | AF173244 | AF173276 | AF334338 | DQ201429 | AY310173 | AY310266 | AY310205–7 | |

| Paralamyctes grayi | AF173242 | AF334309 | AF334354 | AY305475 | AY305519 | AY305606–9 | ||

| Craterostigmomorpha | ||||||||

| Craterostigmidae | Craterostigmus tasmanianus | AF000774 | AF000781 | AF370860 | AF370835 | AF240793 | AY310253-4 | AF240907–8 |

| Scolopendromorpha | ||||||||

| Scolopendridae | Cormocephalus monteithi | AF173249 | AF173280 | AF370861 | DQ201430 | AY310168 | AY310251 | AY310190–2 |

| Scolopendra viridis | DQ201419 | DQ201421 | DQ201425 | DQ201431 | AF240812 | AY310293 | AF240964–6 | |

| Rhysida nuda | AF173252 | AF173282 | AY288722 | DQ201432 | AY310176 | AY310283 | AY310222–4 | |

| Cryptopidae | Cryptops spinipes/C. hyalinus | AY288693 | AY288709 | AY288724 | AY288743 | AF240790 | AY310248 | AF240899–900 |

| Scolopocryptops sexspinosus | AY288694 | AY288710 | AY288726 | AY288745 | AF240810 | AY310290 | AF240958–60 | |

| Theatops posticus | AY288695 | AY288727 | AY288746 | AY310182 | AY310296 | AY310240–2 | ||

| Geophilomorpha | ||||||||

| Ballophilidae | Ballophilus australiae | AF173258 | AF173291 | AY310167 | AY310247 | AY310187–9 | ||

| Geophilidae | Geophilus electricus/G. vittatus | AY288700 | AY289184 | AY288732 | AY288750 | AF240796 | AY310259 | AF240915–6 |

| Tuoba sydneyensis | AF173260 | AY288751 | AY310181 | AY310295 | AY310237–9 | |||

| Tasmanophilus opinatus | AF173259 | AF173286 | AY288752 | AY310180 | AY310294 | AY310234–6 | ||

| Zelanion antipodus | AF173261 | DQ201422 | AY288734 | AY310183 | AY310299-300 | AY310243–5 | ||

| Ribautia n.sp. | AF173263 | AF173287 | AY288736 | AY288755 | AY310175 | AY310282 | AY310219–21 | |

| Pachymerium ferrugineum | AY288702 | AF370803 | AF370863 | AF370838 | AF240807 | AY310281 | AF240949–50 | |

| Linotaeniidae | Strigamia maritima/S. bothriopa | AF173265 | AF173290 | AY288733 | AY288753 | AY310177 | AY310284 | AY310225–7 |

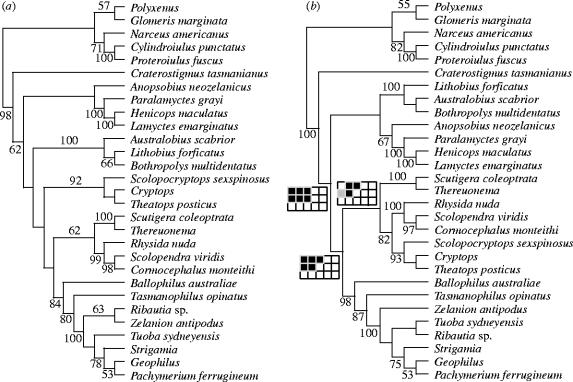

Figure 2.

Cladograms for the combined analyses under parameter set 121 for (a) all molecular data analysed under direct optimization (with 100 replicates of random addition sequence followed by TBR branch swapping and tree fusing) and (b) the simultaneous analysis of all molecular and morphological data analysed under iterative pass optimization (with 10 replicates of random addition sequence followed by TBR branch swapping). Numbers on nodes represent jackknife frequencies greater than 50%. Three nodes that conflict with the morphological tree represented in figure 1 show the corresponding Navajo rugs (see legend for Navajo rug in the lower left corner of figure 1; black squares indicate monophyly, open squares represent non-monophyly, and grey squares indicate monophyly under some of the most parsimonious trees).

(b) Morphological data

The morphological matrix is based on our previously published data matrix (Edgecombe & Giribet 2004) and refined for the current implementation of taxa (see electronic supplementary material). The new version has 153 morphological characters from which characters 28, 38 and 140 were additive; all other characters were considered as non-additive (see electronic supplementary material data matrix).

The morphological data were analysed under parsimony with the computer program TNT (tree analysis using new technology: Goloboff et al. 2003) using a heuristic search with 1000 replicates of random addition sequence followed by TBR (tree bisection and reconnection) branch swapping. Nodal support was calculated with 1000 replicates of parsimony jackknifing (Farris 1997).

(c) Molecular data

The molecular data include the four genes reported in our earlier study of centipede relationships (Edgecombe & Giribet 2004) together with the three genes reported by Regier et al. (2005). Table 1 gives the GenBank accession numbers for the sequences used in this study. New sequences were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers DQ201417–DQ201432. Detailed protocols about amplifying and sequencing these gene fragments are described in published sources (Regier & Shultz 1997, 2001a; Edgecombe et al. 2002). New cytochrome c oxidase subunit I sequences (COI hereafter) were obtained using primer pair LCO1490 (Folmer et al. 1994) and HCOoutout (5′-GTA AAT ATA TGR TGD GCT C-3′), which amplifies a 813 bp fragment. HCOoutout is superior to the widely used primer HCO2198 (Folmer et al. 1994).

Molecular data were analysed under direct optimization (Wheeler 1996) using parsimony as an optimality criterion in the computer program POY (Wheeler et al. 2002). 18S rRNA and 28S rRNA were analysed in combination because they evolve as part of the same locus and the 28S rRNA gene was represented by the small D3 expansion fragment. The complete 18S rRNA was divided into 26 fragments according to internal primers and secondary structure features (Giribet 2001, 2002b); one of these fragments was inactivated from the analyses due to extreme length variation. The 28S rRNA D3 expansion fragment was divided into four segments from which two were inactivated. The 16S rRNA gene was analysed as a single partition divided into nine fragments, two of which were also inactivated. These three genes show length variation and therefore were analysed under direct optimization. The remaining genes (COI, elongation factor-1α [EF1α], elongation factor 2 [EF2], and RNA polymerase subunit II [POLII]) showed no length variation and were treated as prealigned (analysed under static homology). The implied alignment (Wheeler 2003a) under the optimal parameter set (see below) resulted in more than 8 kb as follows: 2431 bp of ribosomal nuclear genes, 404 bp of 16S rRNA, 813 bp of COI, 1131 bp of EF1α, 2184 bp of EF2, and 1062 bp of POLII.

Phylogenetic analyses consisted of 100 replicates of random addition followed by TBR branch swapping and several rounds of tree fusing (Goloboff 1999). Each locus analysis was repeated for a total of 15 analytical parameters varying the ratio between gaps and transversions (for the static fragments only five parameters could be analysed because there are no gaps) as well as the ratio between transversions and transitions (Wheeler 1995). Such analyses were used to test nodal stability to parameter variation (Giribet 2003) and are summarized as sensitivity plots (‘Navajo rugs’). Furthermore, a combined analysis of all molecular partitions (hereafter referred to as MOL) was repeated for the 15 analytical parameters.

Nodal support was measured via 1000 replicates of jackknifing as implemented in POY. All analyses were conducted on a parallel cluster with 30 dual-processor nodes at Harvard University (see darwin.oeb.harvard.edu).

(d) Combined analysis and congruence

The simultaneous analysis of all the data (referred to as TOT) was conducted in POY as per the molecular-only analyses. A modified version of the incongruence length difference (ILD) measure (Mickevich & Farris 1981) was used to provide a rough measure of congruence among data partitions in order to choose our favoured parameter set (Wheeler 1995). Although it has been explicitly stated that this modified ILD is not an accurate measure of character congruence, empirical analyses with multiple datasets show that different measures of congruence may coincide around an area of maximum congruence (Aagesen et al. 2005).

The combined analysis for the favoured parameter set under direct optimization was reanalysed under the more sophisticated iterative pass algorithm (Wheeler 2003b), which uses three terminals instead of two for optimizing nodes. This results in topologies that are much shorter (more parsimonious) than the direct optimization cladograms. Iterative pass has larger memory requirements than direct optimization, which prohibited us from conducting all initial analyses this way. However, iterative pass calculations are more precise than those of direct optimization and therefore convergence upon the same topology is frequent. For this reason we only conducted 10 replicates of random addition followed by TBR.

Nodal support for the optimal cladogram was measured with parsimony jackknifing.

3. Results

(a) Morphological analysis

The morphological data matrix resulted in two trees of 241 steps (consistency index=0.77; retention index=0.91). These two trees differ only in the internal structure of Geophilidae (here represented by Geophilus, Tuoba, Tasmanophilus, Zelanion, Ribautia and Pachymerium). One of them, with unambiguous changes mapped (see electronic supplementary material for character descriptions), is shown in figure 1. The analysis shows monophyly of Chilopoda and of all the centipede orders represented by more than one taxon, and all these clades have a jackknife frequency (JF hereafter) of 100% except for Lithobiomorpha (91% JF). The tree also finds support for the monophyly of the higher-level groupings Pleurostigmophora (92% JF), Phylactometria (86% JF) and Epimorpha (94% JF), each of those clades being supported by at least five unambiguous apomorpies. With the exception of the family Cryptopidae (Cryptops, Scolopocryptops and Theatops), all other families represented by more than one species are monophyletic.

(b) Molecular and combined analyses

The congruence analysis identified parameter set 121 as optimal for the combination of all data (table 2), but 111 and 141 have ILD values very similar to those of 121. Both trees are similar to the 121 tree (figure 2b) in that Craterostigmus is resolved as sister group to all other centipedes and in finding a clade composed of the two epimorphic orders together with Scutigeromorpha. However, in the 111 tree Scutigeromorpha is sister to Geophilomorpha whereas it is sister to Scolopendromorpha under the two other parameter sets. When evaluating jackknife support for the different partitions under the optimal parameter set, the mitochondrial genes 16S rRNA and COI basically find support only for Scutigeromorpha and Geophilidae+Linotaeniidae (Strigamia), while all the other markers were able to provide support for several additional nodes, such as Chilopoda (61–71% JF in all the other partitions), Scolopendromorpha (75% JF for ribosomal), Scolopendridae (Cormocephalus, Scolopendra, and Rhysida; 68–100% JF) and Lithobiidae (Lithobius, Australobius, and Bothropolys; 93–100% JF; not supported for POLII). Lithobiomorpha is recovered under the ribosomal and EF-1α analyses, but with JF less than 50%. Only a few morphologically anomalous nodes showed JF above 50%, and those only occurred in some of the protein coding genes (EF1α, EF2 and COI).

Table 2.

Weighted steps for each analysis at different parameter sets (ranging from 110 to 481; these three numbers indicate indel: transversion: transition ratios) and ILD values. (RIB: 18S+28S rRNA; MOR: morphology; MOL: all molecular partitions; TOT: MOR+MOL. Parameter set 121, shown in boldface, maximizes overall congruence.)

| RIB | 16S | COI | EF1a | EF2 | POL | MOR | MOL | TOT | ILD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 110 | 1003 | 566 | 1002 | 1310 | 2826 | 1671 | 241 | 8582 | 8865 | 0.0277 |

| 111 | 2012 | 1100 | 2151 | 3430 | 7332 | 4283 | 241 | 20661 | 20981 | 0.0206 |

| 121 | 3059 | 1700 | 3213 | 4812 | 10336 | 6056 | 482 | 29659 | 30252 | 0.0196 |

| 141 | 5071 | 2852 | 5256 | 7457 | 16078 | 9462 | 964 | 46981 | 48120 | 0.0204 |

| 181 | 9081 | 5131 | 9313 | 12720 | 27463 | 16210 | 1928 | 81507 | 83779 | 0.0231 |

| 210 | 1432 | 644 | 1002 | 1310 | 2826 | 1671 | 482 | 9143 | 9693 | 0.0336 |

| 211 | 2507 | 1194 | 2151 | 3430 | 7332 | 4283 | 482 | 21315 | 21900 | 0.0238 |

| 221 | 3980 | 1866 | 3213 | 4812 | 10336 | 6056 | 964 | 30825 | 31961 | 0.0230 |

| 241 | 6848 | 3163 | 5256 | 7457 | 16078 | 9462 | 1928 | 49284 | 51524 | 0.0259 |

| 281 | 12580 | 5743 | 9313 | 12720 | 27463 | 16210 | 3856 | 86076 | 90511 | 0.0290 |

| 410 | 2176 | 754 | 1002 | 1310 | 2826 | 1671 | 964 | 10186 | 11257 | 0.0492 |

| 411 | 3341 | 1311 | 2151 | 3430 | 7332 | 4283 | 964 | 22376 | 23513 | 0.0298 |

| 421 | 5561 | 2090 | 3213 | 4812 | 10336 | 6056 | 1928 | 32945 | 35126 | 0.0322 |

| 441 | 9950 | 3602 | 5256 | 7457 | 16078 | 9462 | 3856 | 53491 | 57820 | 0.0373 |

| 481 | 18696 | 6614 | 9313 | 12720 | 27463 | 16210 | 7712 | 94417 | 103095 | 0.0424 |

The combined analyses for all genes and for all data (molecules+morphology) show that deep, inter-ordinal relationships under parameter set 121 are weakly supported (figure 2) and are grossly incongruent with morphology (figure 1). In both cases, Craterostigmus is the sister group to all other centipedes (figure 2a,b), a result that is also found in the EF2 tree. A position of Craterostigmus near the outgroup is also found for the other two nuclear protein coding genes (trees not shown) and appears under a diverse set of parameters for these genes. In the simultaneous analysis of all data, Lithobiomorpha is sister group to a clade containing Scutigeromorpha, Scolopendromorpha and Geophilomorpha, although neither this node nor that uniting Scutigeromorpha and Scolopendromorpha have substantial jackknife support (figure 2b). Similar results are found in the tree for all the combined molecular data, except that in this case Lithobiomorpha and Scolopendromorpha are each paraphyletic (figure 2a). For the molecular data, morphologically anomalous nodes that show JFs above 50% are Scutigeromorpha+Scolopendridae (62% JF) and the basal resolution of Craterostigmus (likewise 62% JF).

The scheme of ordinal relationships depicted in figure 2 is optimal only under a subset of the explored parameter space, generally those with lower gap costs (see Navajo rugs in figure 2b). It is overturned in favour of the morphological cladogram at higher gap costs (figure 1).

4. Discussion

The three nuclear protein coding genes comprise 55% of the total data and contribute between 50 and 75% of the overall molecular length, depending on the parameter set analysed (table 2), and thus they exercise a major contribution to the overall topology. Under equal weights, each of the individual nuclear protein coding genes contributes at least ca 70% more length than the combined ribosomal nuclear genes, while these have a similar contribution to the mitochondrial protein coding gene. When ignoring transitions (right column in the Navajo rugs), an analytical condition that approaches previous treatments that discarded third position information (e.g. Regier et al. 2005), there is no support for the deepest nodes from the topology shown in figure 2b, but instead the data converge on the morphological/traditional view, with each of Pleurostigmophora, Phylactometria and Epimorpha monophyletic (figure 1). This is not interpreted as a justification for excluding third positions but just an observation probably derived from the decrease in the overall contribution of the protein-coding genes to the topology and therefore as an additional indicator that the major conflict between the topologies shown in figures 1 and 2 is due to the signal in these markers, as stated by Regier et al. (2005).

Comparing the results at low gap costs (upper left corner of the Navajo rugs) with those for higher gap costs (lower right section of the Navajo rugs; except for the rightmost column) indicates that the basal position of Craterostigmus and the sister group relationship between Scutigeromorpha and Scolopendromorpha (figure 2b) are driven by the protein-coding genes, which conflict with the signal from morphology or from the ribosomal genes. When evaluating each gene independently (results not shown; see discussion above) it is evident that no single partition provides strong support (measured with jackknifing) or stability (measured by the strict consensus of all the trees obtained under the 15 analytical parameter sets) for the deepest divergences. This applies as well to the nuclear ribosomal genes, which showed a high degree of stability in previous analyses with a much denser taxon sampling (Edgecombe et al. 1999; Edgecombe & Giribet 2002, 2004), but not here. However, it is clear that the number of nodes with JF >90% increases as more data are added, with a maximum in the trees where all molecular data are added (figure 2), although these concentrate in the shallower nodes.

The contribution of the two mitochondrial genes is mostly restricted to the shallower nodes, as expected by their rate of evolution. Analysis of 16S rRNA under parameter set 121 resolves monophyly of Chilopoda (66% JF), Scutigeromorpha (99% JF), Cryptopidae, Scolopendridae, Henicopidae and Geophilomorpha (67% JF), but is otherwise unresolved. COI resolves more nodes, although in this case some well supported nodes are not supported by any other sets of data (Scolopendra+Polyxenus with 89% JF), though it also recognizes groups such as Scutigeromorpha (94% JF) and Geophilomorpha. These results are similar to those of the richer taxon analyses of Edgecombe & Giribet (2004).

Considering morphological evidence (figure 1), it is improbable that the relictual Craterostigmomorpha, currently restricted to Tasmania and both main islands in New Zealand, are the sister group to all remaining centipedes (Regier et al. 2005). This hypothesis forces multiple origins of characters restricted to Phylactometria (e.g. maternal brooding; loss of maxillary nephridia; sclerotization of the maxillipede coxosternite and its embedding above the second trunk segment; lateral testicular vesicles linked by a central deferens duct; internal valves formed by lips of ostiae), as well as forcing convergences or reversals in the characters that support the Pleurostigmophora (e.g. flattening of the head plate; coxal and anal organs; male ‘spinneret’ for deposition of a spermatophore web; tarsus and pretarsus fused as a tarsungulum on the maxillipede).

(a) Concluding remarks

The current analysis is more exhaustive than any previously published centipede phylogeny with respect to the number of sampled characters, but does not match the denser taxon sampling of some previous studies (e.g. Edgecombe & Giribet 2004). Whether the number of characters or the number of taxa is the most important factor in phylogenetic analysis is still debated (e.g. Graybeal 1998; Rokas & Carroll 2005). Adding data may increase nodal support as well as nodal stability (e.g. Edgecombe et al. 2002; Rokas et al. 2003), although this may not necessarily be so for a limited number of loci. In the case of the centipedes, the addition of the nuclear protein-encoding data to our previous datasets positively contributes to resolving the shallower nodes in the tree but adds a strong conflicting signal at deeper nodes. This conflicting signal could, however, be detected by sensitivity analysis since it changes the relative contributions from different partitions, in this particular case by increasing the relative contribution of the ribosomal genes when increasing the cost of indel events. The two conflicting signals are clearly summarized in the Navajo rugs shown in figures 1 and 2.

The results from our analyses are not methodology-specific. Previous analyses of ribosomal genes using a two-step phylogenetic approach (=alignment followed by phylogenetic analysis) (Giribet et al. 1999) are mostly congruent with our current results for these genes using direct optimization. Likewise, our analyses of the nuclear protein-coding genes are largely congruent with the two-step likelihood-based analyses of Regier et al. (2005).

Centipede relationships have been studied using a vast pool of morphological data and a variety of genes. While there is little doubt about centipede relationships from the perspective of morphology (Shinohara 1970; Dohle 1985; Shear & Bonamo 1988; Borucki 1996; Edgecombe et al. 1999; Edgecombe & Giribet 2002, 2004; see figure 1), some molecular analyses have suggested novel topologies that are incongruent with morphology. Considering all of the available data in total for the first time, the number of competing hypotheses for the deepest splits in the centipede tree is narrowed down to two (figures 1 and 2b). Though we cannot fully reject either hypothesis, the congruence of morphology with a subset of the molecular data must be viewed as promising, as is the stability of the morphological topology across a range of analytical parameter sets. Contrary to what happens for the deepest splits, nodal support and clade stability to parameter variation increase by the addition of data for shallower nodes, demonstrating the value of all the data analysed.

In this study we aimed to re-assess centipede relationships by combining all available published evidence to evaluate the signal within each dataset as well as conflicting signals in the published datasets. Given the overall length and the amount of information contributed by each partition, the strongest conflict in the resolution of the centipede phylogeny (figure 1 versus figure 2b) seems to originate in the nuclear protein-coding data. Future work should attempt to increase the amount of information from different loci, such as the nearly complete 28S rRNA (Giribet 2002a; Mallatt & Winchell 2002), as has been done in recent arthropod studies (Mallatt et al. 2004; Giribet et al. 2005).

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by internal funds from Harvard University to G.G. We are indebted to the many colleagues who have provided centipede samples, to Jessica Baker and Akiko Okusu, who assisted with lab work, to Barbara Duperron for artwork, and to three anonymous reviewers and the associate editor, who provided insightful comments that helped to improve an earlier version of this article.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aagesen L, Petersen G, Seberg O. Sequence length variation, indel costs, and congruence in sensitivity analysis. Cladistics. 2005;21:15–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2005.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson L.I, Trewin N.H. An Early Devonian arthropod fauna from the Windyfield Cherts, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Palaeontology. 2003;46:457–509. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00308 [Google Scholar]

- Ax P. Gustav Fischer; Stuttgart: 1999. Das system der Metazoa II. Ein Lehrbuch der phylogenetischen Systematik. [Google Scholar]

- Borucki H. Evolution und phylogenetisches System der Chilopoda (Mandibulata Tracheata) Verhandlungen des naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg. 1996;35:95–226. [Google Scholar]

- Dohle W. Phylogenetic pathways in the Chilopoda. Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde. 1985;55:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe G.D, Giribet G. Myriapod phylogeny and the relationships of Chilopoda. In: Llorente Bousquets J.E, Morrone J.J, editors. Biodiversidad, taxonomía y biogeografía de artrópodos de México: Hacia una síntesis de su conocimiento. Prensas de Ciencias, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; Mexico D.F.: 2002. pp. 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe G.D, Giribet G. Adding mitochondrial sequence data (16S rRNA and cytochrome c oxidase subunit I) to the phylogeny of centipedes (Myriapoda Chilopoda): an analysis of morphology and four molecular loci. J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 2004;42:89–134. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2004.00245.x [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe G.D, Giribet G, Wheeler W.C. Filogenia de Chilopoda: combinando secuencias de los genes ribosómicos 18S y 28S y morfología [Phylogeny of Chilopoda: combining 18S and 28S rRNA sequences and morphology] In: Melic A, de Haro J.J, Méndez M, Ribera I, editors. Filogenia y evolución de Arthropoda. Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa; Zaragoza: 1999. pp. 293–331. [Google Scholar]

- Edgecombe G.D, Giribet G, Wheeler W.C. Phylogeny of Henicopidae (Chilopoda: Lithobiomorpha): a combined analysis of morphology and five molecular loci. Syst. Entomol. 2002;27:31–64. doi:10.1046/j.0307-6970.2001.00163.x [Google Scholar]

- Fahlander K. Beiträge zur Anatomie und systematischen Einteilung der Chilopoden. Zoologiska Bidrag från Uppsala. 1938;17:1–148. [Google Scholar]

- Farris J.S. The future of phylogeny reconstruction. Zool. Scripta. 1997;26:303–311. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.1997.tb00420.x [Google Scholar]

- Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R.C. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol. Mar. Biol. Biotechnol. 1994;3:294–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet G. Exploring the behavior of POY, a program for direct optimization of molecular data. Cladistics. 2001;17:S60–S70. doi: 10.1006/clad.2000.0159. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2001.tb00105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet G. Current advances in the phylogenetic reconstruction of metazoan evolution. A new paradigm for the Cambrian explosion? Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2002;24:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(02)00206-3. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00206-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet G. Relationships among metazoan phyla as inferred from 18S rRNA sequence data: a methodological approach. In: DeSalle R, Giribet G, Wheeler W.C, editors. Molecular systematics and evolution: theory and practice. Birkhäuser; Basel: 2002. pp. 85–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet G. Stability in phylogenetic formulations and its relationship to nodal support. Syst. Biol. 2003;52:554–564. doi: 10.1080/10635150390223730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet G, Carranza S, Riutort M, Baguñà J, Ribera C. Internal phylogeny of the Chilopoda (Myriapoda Arthropoda) using complete 18S rDNA and partial 28S rDNA sequences. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 1999;354:215–222. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0373. doi:10.1098/rstb.1999.0373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giribet G, Richter S, Edgecombe G.D, Wheeler W.C. The position of crustaceans within the Arthropoda—evidence from nine molecular loci and morphology. In: Koenemann S, Jenner R.A, editors. Crustacean issues 16: Crustacea and arthropod relationships. Festschrift for Frederick R. Schram. Taylor & Francis; Boca Raton, FL: 2005. pp. 307–352. [Google Scholar]

- Goloboff P.A. Analyzing large data sets in reasonable times: solutions for composite optima. Cladistics. 1999;15:415–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1999.tb00278.x. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1999.tb00278.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goloboff, P. A., Farris, J. S. & Nixon, K. 2003 TNT: tree analysis using new technology. Version 1.0. Program and documentation available at http://www.zmuc.dk/public/phylogeny/TNT/

- Graybeal A. Is it better to add taxa or characters to a difficult phylogenetic problem? Syst. Biol. 1998;47:9–17. doi: 10.1080/106351598260996. doi:10.1080/106351598260996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus O. “Myriapoda” and the ancestry of the Hexapoda. Annales de la Société entomologique de France (N.S.) 2001;37:105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Mallatt J, Winchell C.J. Testing the new animal phylogeny: first use of combined large-subunit and small-subunit rRNA gene sequences to classify the protostomes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:289–301. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallatt J.M, Garey J.R, Shultz J.W. Ecdysozoan phylogeny and Bayesian inference: first use of nearly complete 28S and 18S rRNA gene sequences to classify the arthropods and their kin. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004;31:178–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.013. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mickevich M.F, Farris J.S. The implications of congruence in Menidia. Syst. Zool. 1981;27:143–158. [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P. The centipedes (Chilopoda) of the Mazon Creek. In: Nitecki M, editor. Mazon Creek fossils. Academic Press; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Regier J.C, Shultz J.W. Molecular phylogeny of the major arthropod groups indicates polyphyly of crustaceans and a new hypothesis for the origin of hexapods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1997;14:902–913. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier J.C, Shultz J.W. Elongation factor-2: a useful gene for arthropod phylogenetics. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2001;20:136–148. doi: 10.1006/mpev.2001.0956. doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.0956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regier J.C, Shultz J.W. A phylogenetic analysis of Myriapoda (Arthropoda) using two nuclear protein-encoding genes. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2001;132:469–486. doi:10.1006/zjls.2000.0277 [Google Scholar]

- Regier J.C, Wilson H.M, Shultz J.W. Phylogenetic analysis of Myriapoda using three nuclear protein-coding genes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2005;34:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokas A, Carroll S.B. More genes or more taxa? The relative contribution of gene number and taxon number to phylogenetic accuracy. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1337–1344. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi121. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokas A, Williams B.L, King N, Carroll S.B. Genome-scale approaches to resolving incongruence in molecular phylogenies. Nature. 2003;425:798–804. doi: 10.1038/nature02053. doi:10.1038/nature02053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweigert V.G, Dietl G. Ein fossiler Hundertfüsser (Chilopoda, Geophilida) aus dem Nusplinger Plattenkalk (Oberjura, Südwestdeutschland) Stuttgarter Beitäger zur Naturkunde, B (Geologie und Paläontologie) 1997;254:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Shear W.A, Bonamo P.M. Devonobiomorpha, a new order of centipeds (Chilopoda) from the middle Devonian of Gilboa, New York State, USA, and the phylogeny of centiped orders. Am. Mus. Novit. 1988;2927:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Shear W.A, Jeram A.J, Selden P.A. Centipede legs (Arthropoda Chilopoda, Scutigeromorpha) from the Silurian and Devonian of Britain and the Devonian of North America. Am. Mus. Novit. 1998;3231:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara K. On the phylogeny of Chilopoda. Proc. Jpn. Soc. Syst. Zool. 1970;6:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Shultz J.W, Regier J.C. Progress toward a molecular phylogeny of the centipede orders (Chilopoda) Entomol. Scand. Suppl. 1997;51:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff K.W. Klassen und Ordnungen des Tierreichs, 5, abt. 2, Buch 1. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft; Leipzig: 1902–1925. Chilopoda. pp. 725. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler W.C. Sequence alignment, parameter sensitivity, and the phylogenetic analysis of molecular data. Syst. Biol. 1995;44:321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler W.C. Optimization alignment: the end of multiple sequence alignment in phylogenetics? Cladistics. 1996;12:1–9. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.1996.tb00189.x [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler W.C. Implied alignment: a synapomorphy-based multiple-sequence alignment method and its use in cladogram search. Cladistics. 2003;19:261–268. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00369.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler W.C. Iterative pass optimization of sequence data. Cladistics. 2003;19:254–260. doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00368.x [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler W.C, Gladstein D, De Laet J. American Museum of Natural History; New York: 2002. POY version 3.0. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.