Abstract

The contribution of sexual selection to brain evolution has been little investigated. Through comparative analyses of bats, we show that multiple mating by males, in the absence of multiple mating by females, has no evolutionary impact on relative brain dimension. In contrast, bat species with promiscuous females have relatively smaller brains than do species with females exhibiting mate fidelity. This pattern may be a consequence of the demonstrated negative evolutionary relationship between investment in testes and investment in brains, both metabolically expensive tissues. These results have implications for understanding the correlated evolution of brains, behaviour and extravagant sexually selected traits.

Keywords: brain, neocortex, cognition, testes, Chiroptera, sexual selection

1. Introduction

Sexual selection is a potent evolutionary force (Darwin 1871). Yet despite recognition that variation in brain structure and function contributes to species differences in courtship signalling and perception (Balaban 1997; Madden 2001), patterns of sexual receptivity and arousal (Ferris et al. 2004), pair bonding (Young & Wang 2004), and parental care and territorial aggression (Young et al. 1998), the role of sexual selection on brain size evolution has, with few exceptions (Pawlowski et al. 1998; Madden 2001; Garamszegi et al. 2005), received little study.

Allometry explains much of the variation in brain size among species (Baron et al. 1996; Pagel & Harvey 1988b; Jones & MacLarnon 2004). Various adaptive explanations for the remaining variation include the need for enhanced or specialized sensory systems (Barton et al. 1995), diet (Jones & MacLarnon 2004) and spatial ecology (Safi & Dechmann 2005). In addition, the ‘social brain’ (or ‘Machiavellian intelligence’) hypothesis, which contends that increasing social complexity enhances cognitive arms races in which relatively large-brained individuals are better able to manipulate the behaviour of others to favour the manipulator's own needs (Byrne & Whiten 1997), has been supported by positive relationships between brain size and social group size (Dunbar 1995) or deception rate (Byrne & Corp 2004) among primates.

Recent theoretical and empirical developments in sexual selection theory (Chapman et al. 2003) suggest a corollary hypothesis in which males and females are jointly under selection to subvert the reproductive investment made by their sexual partners, and resist being subverted by them, thus generating sexually antagonistic coevolution for cognition (Rice & Holland 1997). This sexual conflict hypothesis predicts that species breeding promiscuously will have relatively larger brains than species with genetic monogamy.

We propose here an additional hypothesis generated from sexual selection theory. Because relatively large brains are metabolically costly to develop and maintain, changes in brain size may be accompanied by compensatory changes in other expensive tissues. This ‘expensive tissue’ hypothesis for brain size evolution has received empirical support from studies of the comparative relationship between brain and gastrointestinal tract mass among anthropoid primates (Aiello & Wheeler 1995), but not from an analysis of intestine length in bats (Jones & MacLarnon 2004). However, this hypothesis has not been considered in any taxon with regard to ornaments, weapons or sexual organs functioning in reproductive competition. Such sexually selected traits can also be costly, as indicated by their condition-dependence (Johnstone 1995; Cotton et al. 2004). The ‘expensive sexual tissue’ hypothesis thus contends that more intense sexual selection will constrain the evolution of enhanced brain size as a result of energetic trade-offs with costly sexual organs, ornaments or armaments.

Here, we analyse comparative data on total brain and neocortex dimension, testis mass, and social and mating systems for 334 Chiroptera species to test predictions of the social brain, sexual conflict and expensive sexual tissue hypotheses for brain evolution in this large and ecologically diverse mammalian clade. It is important to note that, with few exceptions (McCracken & Wilkinson 2000), male bats are not more ornamented than females. Males of many bat species are, however, well equipped with relatively large testes, which has been interpreted as an adaptive response to postcopulatory sexual selection (Hosken 1997, 1998; Wilkinson & McCracken 2003). Testicular tissue can represent a substantive energetic investment (Kenagy & Trombulak 1986), and an extraordinary range of combined testes mass has been documented across bat species: from 0.12 to 8.4% of body mass, which exceeds that of any other mammalian order (Wilkinson & McCracken 2003). Primates by comparison, which have been widely used as evidence that sexual selection influences testes size, exhibit combined testis mass ranging only from 0.02 to 0.75% of body mass (Harvey & Harcourt 1984). We thus tested the expensive sexual tissue hypothesis by comparatively examining the relationship between relative dimension of brains and testes.

2. Material and methods

(a) Data acquisition

Data were assembled from the literature for 334 bat species. Species names were converted before analysis into the taxonomy of Wilson & Reeder (1993), and names that could not be reconciled were excluded. Brain dimension data include total brain mass (mg; N=313 species) and raw volume of the neocortex (isocortical grey+underlying white matter; mm3; N=253 species; Baron et al. 1996). Mean species brain values were analysed as sex-specific brain values are unavailable for most species. Testis data are the combined mass of the pair of testes from males in breeding condition (g; N=103 species), with mass either directly measured or else estimated from testicular volume (Wilkinson & McCracken 2003). Adult body mass (g) values used were those reported in the literature providing the brain and testis data. Bat social and breeding systems are challenging to categorize, as they fall more on a continuum and genetic data on patterns of parentage are rare. To explore the relationship between social structure and brain dimension, we categorized species according to the structural roosting association as single-male/single-female, single-male/multiple-female or multiple-male/multiple-female (N=59 species; McCracken & Wilkinson 2000). For those species with more detailed information on mating behaviour available, female remating behaviour was categorized as either promiscuous or not promiscuous (N=44 species; McCracken & Wilkinson 2000; Wilkinson & McCracken 2003) and mating systems were categorized as monogamous, polygynous or polygynandrous (N=45 species; McCracken & Wilkinson 2000; Wilkinson & McCracken 2003). Diet was categorized (N=334 species) as either ‘fruit’ (fruit, flowers, pollen and nectar) or ‘non-fruit’ (diet other than fruit, flowers, pollen and nectar; Jones & MacLarnon 2004). All raw data used in analyses are in the electronic supplementary material and are also available directly from the authors.

(b) Statistical analyses

To control for allometry in the species-level analyses, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used with body size treated as a covariate. We investigated the amount of similarity among species in brain and testis data that was due to shared evolutionary history using the spatial autocorrelation statistic, Moran's I (Gittleman & Kot 1990), and found all to be significant at the level of species within genera (results not presented). Appropriate statistical methods that consider phylogenetic distribution of character states could not be effectively employed with the discrete analyses of female promiscuity, mating system and roosting association, as the character distributions, coupled with the current lack of resolution of the Chiroptera clade (Jones et al. 2002), resulted in low power to detect relationships. We were, however, able to control for shared ancestry by analysing independent contrasts of the size-corrected brain and testis residuals generated by the CRUNCH algorithm of the Caic program (Purvis & Rambaut 1995) and using a bat supertree phylogeny (Jones et al. 2002) with estimates of branch lengths based on molecular sequence divergences (Jones et al. 2005). Size-corrected residuals were generated from regressions of brain and testis mass on body mass. Repeating the analyses with the supertree recoded following the recent family-level phylogeny of Teeling et al. (2005) to generate the contrasts did not qualitatively affect the results. Sensitivity of the results to homoscedasticity in the contrasts (caused by inadequate branch length transformation and other deviations from the assumptions of the independent contrasts method) was investigated in two ways: (i) by repeating the contrast analysis with equal branch lengths and (ii) by examining the effects of removing contrasts that had a studentized residual greater than 3. In both cases, the correlation between brain size and testis mass either increased in significance or remained qualitatively unchanged. Correlations between independent contrasts of variables were examined using least squares linear regressions with the models constrained to go through the origin. Results from species-level analyses can also be confounded by physiological and ecological ‘grade shifts,’ as previous studies have demonstrated significant effects of echolocational ability and diet (fruit versus non-fruit) on relative brain mass in bats (Barton et al. 1995; Jones & MacLarnon 2004; Safi & Dechmann 2005). We thus took a conservative approach, investigating each correlation both within all species and discretely for each of the above grades. All continuous variables were loge transformed prior to statistical analysis, and all statistical tests were two-tailed and performed (for species-level analyses) using Jmp version 5.1 and (for independent contrast analyses) using Spss v. 12.

3. Results

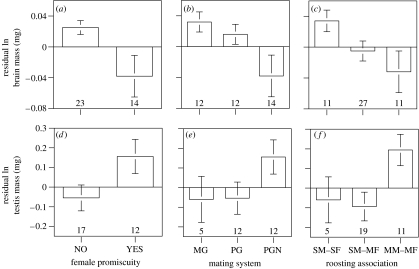

To determine if brain size has been influenced by social complexity or sexual conflict we examined the relationship between both the social system (i.e. roosting association) and the mating system and brain size evolution in bats using data on both total brain mass and volume of the neocortex. Relative neocortex size provides one of the clearest indicators of general brain evolution (Baron et al. 1996) and has been treated as a proxy for enhanced cognitive abilities (Dunbar 1995; Byrne & Corp 2004). After controlling for allometric differences associated with body size, we found highly significant relationships between both brain traits and female promiscuity and mating system and marginally non-significant relationships with roosting association (table 1). Trait differences among treatment groups are illustrated using residuals in figure 1.

Table 1.

Results (F statistic and p value) of species-level analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) for the dependent variables: brain mass, neocortex volume and testis mass on various measures of mating/social system organization, with body mass treated as a covariate.

| independent variables | total brain mass (ln mg) | neocortex volume (ln mm3) | testis mass (ln mg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| female promiscuity | 14.08 | <0.001 | 15.88 | <0.001 | 30.43 | <0.0001 |

| body mass (ln g) | 1548.49 | <0.0001 | 820.88 | <0.0001 | 89.27 | <0.0001 |

| mating system | 6.93 | <0.005 | 7.33 | <0.005 | 16.37 | <0.0001 |

| body mass (ln g) | 1516.78 | <0.0001 | 769.76 | <0.0001 | 92.61 | <0.0001 |

| roosting association | 2.65 | 0.08 | 2.76 | 0.07 | 11.24 | <0.0005 |

| body mass (ln g) | 1484.55 | <0.0001 | 804.57 | <0.0001 | 100.49 | <0.0001 |

Figure 1.

Mean residual ln brain mass (a–c) and testis mass (d–f) for bat species relative to the occurrence of female promiscuity (a,d), their mating system (b,e; MG, monogamy; PG, polygyny; PGN, polygynandry), and their roosting association (c,f; SM–SF, single male, single female; SM–MF, single male, multi female; MM–MF, multi male, multi female). Residuals were generated from regression of ln brain mass or ln testis mass on ln body mass, with regressions performed separately by family as partial phylogenetic control. These data are for illustrative purposes only; all conclusions from discrete analyses are based on ANCOVAs (table 1). Relationships for residual ln neocortex volume (not shown) are qualitatively similar to those illustrated for total brain mass. Error bars equal one s.e.m. Number of species indicated at base of columns.

Relatively small brains are found in species that have females that mate promiscuously, are polyganyndrous and assemble in multi-male/multi-female roosts (figure 1a–c). Male promiscuity, by contrast, had no evolutionary influence on relative brain dimension (compare ‘monogamy’ and ‘polygyny’ in figure 1b). The strong trend towards diminishing brain size as complexity in roosting group composition increases (figure 1c) is opposite to the pattern predicted by the social brain hypothesis (Dunbar 1995). We believe that some caution is warranted in interpreting this result, however, as social group stability and the number of individuals engaged in regular interactions (for which there is insufficient information available from most species to assess) may be more important to brain evolution than the composition or size of a colony (Wilkinson 2003). The finding that species in which females are guarded and presumably inseminated by only a single male within a breeding cycle have relatively large brains (figure 1a) similarly supports rejection of the sexual conflict hypothesis. Nevertheless, all of the observed relationships implicate a strong association between sexual selection and brain dimension among bat species.

As previously reported (Wilkinson & McCracken 2003), we found that relative testis mass covaries with female promiscuity and roosting association (table 1; figure 1d,f). We additionally demonstrate here that it is female promiscuity, and not male opportunity to inseminate multiple females, that is associated with increases in relative testis mass (compare ‘monogamy’ and ‘polygyny’ with ‘polygynandry’ in figure 1e). Collectively, these results indicate that relative testis mass is a robust index of the intensity of sperm competition and the genetic breeding system in bats. With regard to the expensive tissue hypothesis, note that the distribution of residual brain mass among treatment groups (figure 1a–c) mirrors that of residual testis mass (figure 1d–f). It is further worth noting that the bat species bearing the relatively largest testes, for which brain dimension data is also available, Myotis albescens (Vespertilionidae), invests more than twice as much in testes as in brains (6.7 versus 3.2% of body mass, respectively).

Results presented above should be cautiously interpreted, given that both brain dimension and breeding system may exhibit phylogenetic inertia (Jones & MacLarnon 2004), and because breeding system is expected to covary with foraging ecology (Emlen & Oring 1977), which is non-randomly distributed across the bat clade and known to select on relative brain size in bats (de Winter & Oxnard 2001; Safi & Dechmann 2005). We, therefore, examined the relationship between continuous variation in brain and testis mass across species while correcting for phylogeny, allometry and ecological grades associated with diet and echolocation. A significant negative relationship between independent contrasts in residual brain mass and independent contrasts in residual testis mass was found in a regression analysis of all species (n=57, slope=−0.069, t=−2.23, r2=0.08, p=0.029). Interestingly, when controlling for grade shifts, this relationship was found to be significant and negative for echolocating species (n=46; slope=−0.079, t=−2.35, r2=0.11, p=0.023), but not for non-echolocating species (n=10; slope=0.042, t=1.27, r2=0.15, p=0.236). Qualitatively similar statistical results were found when controlling for diet (not shown). The relationship between contrasts in residual ln neocortex volume and residual ln testis mass were not significant (all species: n=52, slope=−0.043, t=−1.29, r2=0.03, p=0.204; echolocating: n=41; slope=−0.059, t=−1.61, r2=0.07, p=0.12; non-echolocating: n=10; slope=0.035, t=0.58, r2=0.04, p=0.57).

4. Discussion

We postulate that the most likely explanation for negative covariation between brains and testes in bats is that these metabolically expensive organs energetically trade-off against one another. A growing body of evidence indicates that costly sexually selected traits (including testis and ejaculatory traits) can trade-off against other energetically expensive but important characters, such as immune function (Siva-Jothy et al. 1998; Verhulst et al. 1999; Hosken 2001; Fedorka et al. 2004; Simmons & Roberts 2005). Comparative analyses of fruit flies have shown that costly spermatogenesis can trade-off with developmental life histories, such as the onset of reproductive maturity (Pitnick et al. 1995; Pitnick 1996; Pitnick & Miller 2000). Further, experimentally ablating the precursor cells that normally give rise to testes result in disproportionately larger horns (a secondary sexual trait) in the scarab beetle, Onthophagus taurus, demonstrating that even distant body parts may rely on a common resource pool for their developmental growth (Moczek & Nijhout 2004). A similar trade-off between testes and brains in bats is perhaps not surprising given their extreme ‘economy of design’ resulting from using an energetically expensive form of locomotion and exploiting food sources that are seasonally variable (Hosken & Withers 1997).

The finding of a negative evolutionary relationship between brains and testes in echolocating (and non-fruit eating) bats, but not in non-echolocating (or fruit-eating) bats, may be attributable to the former group of species having more constrained energy budgets, as suggested by their greater use of torpor than non-echolocating species, even in the tropics (Hosken & Withers 1997). This difference in energy budgets may be due in part to their smaller body size (mean±s.e. body mass: echo: 18.32±1.32 g; non-echo: 197.56±33.64 g; for mammals weighing less than 100 g, maintaining gonadal tissue represents 5–10% of basal metabolic rate (Kenagy & Trombulak 1986)). In addition, echolocating species have relatively larger surface areas (Hosken & Withers 1997), and more variable relative testis mass than do non-echolocating species (regressions: echo: ln testis mass contrasts=0.844×ln body mass contrasts, n=65, r2=0.38; non-echo: ln testis mass contrasts=0.678×ln body mass contrasts, n=14, r2=0.48). Finally, given that the energetic expense of reproduction often has long-term costs in terms of body condition (Clutton-Brock et al. 1989) and survival (Bell 1980), it is noteworthy that bat longevity is on average 3.5 times greater than for non-flying placental mammals of similar size (Wilkinson & South 2002). It thus appears the extreme investment in testes is not energetically accommodated by a reduction in somatic maintenance.

The possibility that investment in either testes or brains constrains investment in the other has important and novel implications for sexual selection theory. To the extent that relative brain dimension influences reproductive behaviours (Balaban 1997; Young et al. 1998; Madden 2001; Ferris et al. 2004; Young & Wang 2004), sexual selection favouring greater or lesser investment in resource-intensive organs, ornaments or armaments (e.g. testes, plumage, antlers) will be influenced by selection on brains and behaviour, and vice versa. In cases of extreme investment in ornaments (e.g. peacock's tails) the evolutionary interplay between neurogenesis and secondary sexual traits may have far-reaching effects on the directions and rates at which other traits evolve.

There are at least two alternative or complementary explanations to the expensive tissue hypothesis for the observed brain–testis relationships. First, larger brains take longer to develop, and hence gestation length, maturation time and the duration of parental care may correlate positively with neonatal brain mass (Pagel & Harvey 1988a; Allman et al. 1993; Jones & MacLarnon 2004). Consequently, larger-brained species may tend towards monogamy, given the premium on bi-parental care of offspring. This explanation seems unlikely to contribute substantially to the broader brain–testis relationship, however, given that paternal care is rare in bats, having been documented in only two species (McCracken & Wilkinson 2000). Second, recent studies implicate genetic constraint (e.g. antagonistic pleiotropy) as a possible explanation for the inverse evolutionary brain–testis relationship. A functionally diverse array of genes exhibit coexpression in brain and testis (Wilda et al. 2000; Meizel 2004), defects in testis function tend to be associated with mental retardation (Zechner et al. 2001), and genes associated with cognition and those specific for testicular somatic cells and early stages of spermatogenesis may share a similar genetic architecture characterized by a preponderance of X-linked genes (Wang et al. 2001; Zechner et al. 2001; Divina et al. 2005); but note that genes expressed exclusively during male meiosis exhibit the opposite pattern (Eddy & O'Brien 1998; Betrán et al. 2002). Integrating the contribution of such molecular/developmental mechanisms with a more traditional, life history (energetic) view of trade-offs, to better our understanding of trait evolution, presents a fundamental theoretical and empirical challenge (Barnes & Partridge 2003).

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Bjork, S. Dorus, D. Hosken, T. Karr, T. Starmer, A. Uy, L. Wolf and an anonymous referee for valued discussion or comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript, and B. Byrnes for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Science Foundation grants to S.P. and G.S.W. and an Earth Institute Fellowship to K.E.J.

Footnotes

Present address: Institute of Zoology, Zoological Society of London, Regents Park, London NW1 4RY, UK.

Supplementary Material

References

- Aiello L.C, Wheeler P. The expensive-tissue hypothesis: the brain and the digestive system in human and primate evolution. Curr. Anthropol. 1995;36:199–221. 10.1086/204350 [Google Scholar]

- Allman J, McLaughlin T, Hakeem A. Brain weight and life-span in primate species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:118–122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaban E. Changes in multiple brain regions underlie species differences in complex, congenital behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;100:4873–4878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes A.I, Partridge L. Costing reproduction. Anim. Behav. 2003;66:199–204. 10.1006/anbe.2003.2122 [Google Scholar]

- Baron G, Stephan H, Frahm H.D. Comparative neurobiology in Chiroptera. Volume 1. Macromorphology, brain structures, tables and atlases. Birkhauser; Basel: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barton R.A, Purvis A, Harvey P.H. Evolutionary radiation of visual and olfactory brain systems in primates, bats and insectivores. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 1995;348:381–392. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1995.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell G. The costs of reproduction and their consequences. Am. Nat. 1980;116:45–76. 10.1086/283611 [Google Scholar]

- Betrán E, Thornton K, Long M. Retroposed new genes out of the X in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2002;12:1854–1859. doi: 10.1101/gr.604902. 10.1101/gr.6049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne R.W, Corp N. Neocortex size predicts deception rate in primates. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:1693–1699. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2780. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne R.W, Whiten A, editors. Machiavellian intelligence. Machiavellian intelligence II. Extensions and evaluations. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1997. pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman T, Arnqvist G, Bangham J, Rowe L. Sexual conflict. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2003;18:41–47. 10.1016/S0169-5347(02)00004-6 [Google Scholar]

- Clutton-Brock T.H, Albon S.D, Guinness F.E. Fitness cost of gestation and lactation in wild mammals. Nature. 1989;337:260–262. doi: 10.1038/337260a0. 10.1038/337260a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, Fowler K, Pomiankowski A. Do sexual ornaments demonstrate heightened condition-dependent expression as predicted by the handicap hypothesis? Proc. R. Soc. B. 2004;271:771–783. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2688. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. Murray; London: 1871. [Google Scholar]

- de Winter W, Oxnard C.E. Evolutionary radiations and convergences in the structural organization of mammalian brains. Nature. 2001;409:710–714. doi: 10.1038/35055547. 10.1038/35055547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divina P, Cestmir V, Strnad P, Paces V, Foreft J. Global transcriptome analaysis of the C57BL/6J mouse testis by SAGE: evidence for nonrandom gene order. BMC Genomics. 2005;6:29. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-29. 10.1186/1471-2164-6-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar R.I.M. Neocortex size and group size in primates: a test of the hypothesis. J. Hum. Evol. 1995;28:287–296. 10.1006/jhev.1995.1021 [Google Scholar]

- Eddy E.M, O'Brien D.A. Gene expression during mammalian meiosis. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 1998;37:141–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emlen S, Oring L.W. Ecology, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating systems. Science. 1977;197:215–223. doi: 10.1126/science.327542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorka K.M, Zuk M, Mousseau T.A. Immune suppression and the cost of reproduction in the ground cricket, Allonemobius socius. Evolution. 2004;58:2478–2485. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2004.tb00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferris C.F, et al. Activation of neural pathways associated with sexual arousal in non-human primates. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2004;19:168–175. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10456. 10.1002/jmri.10456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garamszegi L.Z, Eens M, Erritzø J, Møller A.P. Sperm competition and sexually size dimorphic brains in birds. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:159–166. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2940. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittleman J.L, Kot M. Adaptation: statistics and a null model for estimating phylogenetic effects. Syst. Zool. 1990;39:227–231. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey P.H, Harcourt A.H. Sperm competition, testes size, and breeding systems in primates. In: Smith R.L, editor. Sperm competition and the evolution of animal mating systems. Academic Press; New York: 1984. pp. 589–600. [Google Scholar]

- Hosken D.J. Sperm competition in bats. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1997;264:385–392. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0055. 10.1098/rspb.1997.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosken D.J. Testes mass in megachiropteran bats varies in accordance with sperm competition theory. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1998;44:169–177. 10.1007/s002650050529 [Google Scholar]

- Hosken D.J. Sex and death: microevolutionary trade-offs between reproductive and immune investment in dung flies. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:R379–R380. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00211-1. 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00211-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosken D.J, Withers P.C. Temperature regulation and metabolism of an Australian bat, Chalinobus gouldii (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) when euthermic and torpic. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1997;167:71–80. doi: 10.1007/s003600050049. 10.1007/s003600050049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone R.A. Sexual selection, honest advertisement and the handicap principle: reviewing the evidence. Biol. Rev. 1995;70:1–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1995.tb01439.x. 10.1086/418864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K.E, MacLarnon A. Affording larger brains: testing hypotheses of mammalian brain evolution in bats. Am. Nat. 2004;164:E20–E31. doi: 10.1086/421334. 10.1086/421334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K.E, Purvis A, MacLarnon A, Bininda-Emonds O.R.P, Simmons N.B. A phylogenetic supertree of the bats (Mammalia: Chiroptera) Biol. Rev. 2002;77:223–259. doi: 10.1017/s1464793101005899. 10.1017/S1464793101005899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones K.E, Bininda-Emonds O.R.P, Gittleman J.L. Bats, clocks and rocks: diversification patterns in Chiroptera. Evolution. 2005;59:2243–2255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenagy G.J, Trombulak S.C. Size and function of mammalian testes in relation to body size. J. Mammal. 1986;67:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Madden J. Sex, bowers and brains. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2001;268:833–838. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1425. 10.1098/rspb.2000.1425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken G.F, Wilkinson G.S. Bat mating systems. In: Crichton E.G, Krutzsch P.H, editors. Reproductive biology of bats. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 321–362. [Google Scholar]

- Meizel S. The sperm, a neuron with a tail: ‘neuronal’ receptors in mammalian sperm. Biol. Rev. 2004;79:713–732. doi: 10.1017/s1464793103006407. 10.1017/S1464793103006407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moczek A.P, Nijhout H.F. Trade-offs during the development of primary and secondary sexual traits in a horned beetle. Am. Nat. 2004;163:184–191. doi: 10.1086/381741. 10.1086/381741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel M.D, Harvey P.H. How mammals produce large-brained offspring. Evolution. 1988a;42:948–957. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1988.tb02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel M.D, Harvey P.H. The taxon-level problem in the evolution of mammalian brain size: facts and artifacts. Am. Nat. 1988b;132:344–359. 10.1086/284857 [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowski B, Lowen C.B, Dunbar R.I.M. Neocortex size, social skills and mating success in primates. Behaviour. 1998;135:357–368. [Google Scholar]

- Pitnick S. Investment in testes and the cost of making long sperm in Drosophila. Am. Nat. 1996;148:57–80. 10.1086/285911 [Google Scholar]

- Pitnick S, Miller G.T. Correlated response in reproductive and life history traits to selection on testis length in Drosophila hydei. Heredity. 2000;84:416–426. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00679.x. 10.1046/j.1365-2540.2000.00679.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitnick S, Markow T.A, Spicer G.S. Delayed male maturity is a cost of producing large sperm in Drosophila. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1995;92:10 614–10 618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purvis A, Rambaut A. Comparative analysis by independent contrasts (CAIC): an Apple Macintosh application for analyzing comparative data. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1995;11:247–251. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/11.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice W.R, Holland B. The enemies within: intergenomic conflict, interlocus contest evolution (ICE), and the intraspecific Red Queen. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1997;41:1–10. 10.1007/s002650050357 [Google Scholar]

- Safi K, Dechmann D.K.N. Adaptation of brain regions to habitat complexity: a comparative analysis in bats (Chiroptera) Proc. R. Soc. B. 2005;272:179–186. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2924. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons L, Roberts B. Bacterial immunity traded for sperm viability in male crickets. Science. 2005;309:2031. doi: 10.1126/science.1114500. 10.1126/science.1114500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siva-Jothy M.T, Tsubaki Y, Hooper R.E. Decreased immune response as a proximate cost of copulation and oviposition in a damselfly. Physiol. Entomol. 1998;23:274–277. 10.1046/j.1365-3032.1998.233090.x [Google Scholar]

- Teeling E.C, Springer M.S, Madsen O, Bates P, O'Brien S.J, Murphy W.J. A molecular phylogeny for bats illuminates biogeography and the fossil record. Science. 2005;307:580–584. doi: 10.1126/science.1105113. 10.1126/science.1105113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhulst S, Dieleman S.J, Parmentier H.K. A trade-off between immunocompetence and sexual ornamentation in domestic fowl. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4478–4481. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4478. 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.J, McCarrey J.R, Yang F, Page D.C. An abundance of X-linked genes expressed in spermatogonia. Nat. Genet. 2001;27:422–426. doi: 10.1038/86927. 10.1038/86927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilda M, Bächner D, Zechner U, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Vogel W, Hameister H. Do the constraints of human speciation cause expression of the same set of genes in brain, testis, and placenta? Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 2000;91:300–302. doi: 10.1159/000056861. 10.1159/000056861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson G.S. Social and vocal complexity in bats. In: de Waal F.B.M, Tyack P.L, editors. Animal social complexity: intelligence, culture and individualized societies. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2003. pp. 322–341. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson G.S, McCracken G.F. Bats and balls: sexual selection and sperm competition in the Chiroptera. In: Kunz T.H, Fenton M.B, editors. Bat ecology. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2003. pp. 128–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson G.S, South J.M. Life history, ecology and longevity in bats. Aging Cell. 2002;1:124–131. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2002.00020.x. 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2002.00020.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D.E, Reeder D.M. Smithsonian Institution Press; Washington, DC: 1993. Mammalian species of the world. A taxonomic and geographic reference. [Google Scholar]

- Young L.J, Wang Z. The neurobiology of pair bonding. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:1048–1054. doi: 10.1038/nn1327. 10.1038/nn1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L.J, Wang Z, Insel T.R. Neuroendocrine bases of monogamy. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:71–75. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01167-3. 10.1016/S0166-2236(97)01167-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zechner U, Wilda M, Kehrer-Sawatzki H, Vogel W, Fundele R, Hameister H. A high density of X-linked genes for general cognitive ability: a run-away process shaping human evolution? Trends Genet. 2001;17:697–701. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(01)02446-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.