Abstract

The rhodopsin crystal structure provides a structural basis for understanding the function of this and other G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). The major structural motifs observed for rhodopsin are expected to carry over to other GPCRs, and the mechanism of transformation of the receptor from inactive to active forms is thus likely conserved. Moreover, the high expression level of rhodopsin in the retina, its specific localization in the internal disks of the photoreceptor structures [termed rod outer segments (ROS)], and the lack of other highly abundant membrane proteins allow rhodopsin to be examined in the native disk membranes by a number of methods. The results of these investigations provide evidence of the propensity of rhodopsin and, most likely, other GPCRs to dimerize, a property that may be pertinent to their function.

Keywords: visual pigments, crystal structure, phototransduction, signal transduction, all-trans-retinal

BACKGROUND AND SCOPE

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute by far the largest family of cell surface proteins involved in signaling across biological membranes. All GPCRs share a common seven α-helical transmembrane architecture (1). For most GPCRs, the external signal is a small molecule that binds to the membrane-embedded receptor and causes it to undergo a conformational change. The conformational change on the intracellular surface of the receptor results in the binding and activation of several (2, 3) or hundreds (4, 5) of heterotrimeric guanylate nucleotide-binding protein (G protein) molecules by a universal mechanism. Although GPCRs couple to G proteins, these receptors are also referred to as seven-transmembrane receptors, reflecting their seven membrane-embedded helices and additional signaling independent of G proteins (6, 7).

The GPCR superfamily encompasses approximately 950 genes in the human genome, including ~500 sensory GPCRs (8–10). GPCRs modulate an extremely wide range of physiological processes, and mutations in the genes encoding these receptors have been implicated in numerous diseases. It is, thus, not surprising that these receptors form the largest class of therapeutic targets (e.g., see 11–13). Mammalian GPCRs are usually grouped by amino acid sequence similarities into the three distinct families A, B, and C (e.g., see 6, 7). More recently, the International Union of Pharmacology Committee on Receptor Nomenclature and Drug Classification published reports on the nomenclature and pharmacology of GPCRs that consider their predicted structure, pharmacology, and roles in physiology and pathology [(14); see also http://www.iuphar.org/nciuphararti.html and http://www.iuphar-db.org/iuphar-rd/].

In vision, rhodopsin in rod photoreceptors and cone opsins in cone photoreceptors respond to light (15, 16). Their chromophore, 11-cis-retinal, is covalently bound via a protonated Schiff base to the polypeptide chains of each opsin, embedded within the transmembrane domain. Upon absorption of a photon, the chromophore undergoes photoisomerization to all-trans-retinylidene, inducing a correspondent change in the opsin from its inactive to its active conformation. The active form, known as Meta II, then recruits and binds intracellular G proteins, continuing the visual signal cascade that culminates in an electrical impulse to the visual cortex of the brain. Soon after, opsin and the chromophore recombine to regenerate fresh rhodopsin. Progress in understanding how rhodopsin works has been steady during the past 120 years; however, recognition of rhodopsin as a member of the GPCR family, roughly 20 years ago, greatly enhanced interest in this receptor (16a). Remarkable advancements, which have benefited the GPCR field in general, have been achieved from studying rhodopsin. More recently, structural, genetic, and biochemical studies of rhodopsin have revealed unanticipated properties of this receptor, and a number of summary publications are available (References 1 and 16–25 to cite a few). The activation mechanism of rhodopsin has been extensively discussed on the basis of existing data (16, 21, 24, 26). Here, I summarize recent work on rhodopsin in relation to the receptor structure, the ligand-binding site, dimerization as a widespread property of GPCRs, and the interaction with the cognate G protein.

RHODOPSIN

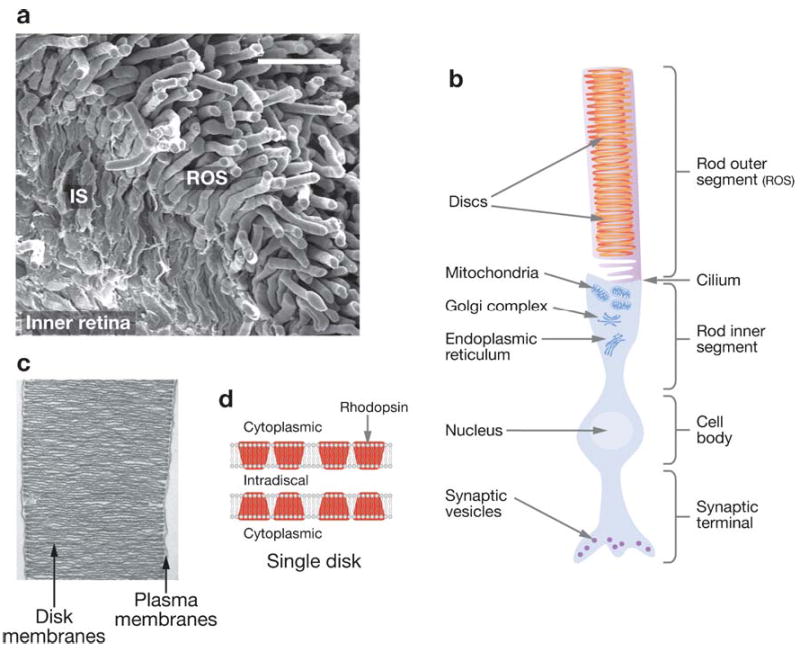

Retinal rod cells (also known as photoreceptor cells) are highly differentiated neurons responsible for detecting photons ( Figure 1) (27). A specialized part of the rod cell, the rod outer segment (ROS) ( Figure 1a,b), contains rhodopsin and auxiliary proteins, which convert and amplify the light signal (28). The system is so exquisitely sensitive that a single photon can be detected [(29), and more recently (30)]. Each mammalian ROS consists of a pancake-like stack of 1000–2000 distinct disks enclosed by the plasma membrane ( Figure 1c). The main protein component (>90%) of the bilayered disk membranes is light-sensitive rhodopsin. Approximately 50% of the disk membrane area is occupied by rhodopsin, whereas the remaining space is filled with phospholipids and cholesterol ( Figure 1d ). Rhodopsin is also present at a lower density in the plasma membrane (31). The ROS of wild-type mice have an average length of 23.6 ± 0.4 μm (32) or 23.8 ± 1.0 μm (33) and contain on average 810 ± 10 disks (33). Given the approximately 6.4 × 106 rods in the mouse retina (34), this translates to ~5 × 109 disks per retina. The total amount of rhodopsin per eye is ~650 pmoles (650 × 10−12 × 6.022 × 1023 = 3.96 × 1014 rhodopsin molecules); thus there are ~8 × 104 rhodopsin molecules per disk. The size of ROS is reduced when animals are exposed for a prolonged period to light, a phenomenon described as photostasis (35) and for which the molecular mechanism has not yet been elucidated. Rhodopsin expression is essential for the formation of the ROS, which are absent in knockout rhodopsin−/− mice (36, 37). The ROS of mice heterozygous for the rhodopsin gene deletion (rhodopsin+/−) have a similar density of rhodopsin, but the ROS volume is reduced by ~60% compared with wild-type mice (33).

Figure 1.

Vertebrate retina and rhodopsin. (a) Scanning electroretinogram of mouse retina [courtesy of Yan Liang (33)]. Rod cells comprise ~70% of all 6.4 million retinal cells, and cone cells represent <2%. Rods are postmitotic neurons with highly differentiated rod outer segments (ROS) connected to the inner segments (IS), which generate proteins and energy to sustain phototransduction events. (b) Diagram depicting the rod cell. The processes in ROS allow rapid transduction of the light signal to graded hyperpolarization of the plasma membrane, ensuing from the decrease of light-sensitive conductance in the ROS cGMP-gated cation channels. In ROS, hundreds of distinct, rhodopsin-loaded disk membranes (20) are enveloped by the plasma membrane. (c) Electron micrograph of isolated ROS from the mouse retina [courtesy of Yan Liang (33)]. The disk membranes consist of a phospholipid bilayer studded with rhodopsin. (d ) Diagram of disk membranes. The main protein of ROS disk membranes is light-sensitive rhodopsin, which occupies 50% of the disk area. The molar ratio between rhodopsin and phospholipids is about 1:60 (for example 138 and 139; reviewed in 140). Multiple techniques suggest that rhodopsin forms oligomeric structures in the native membranes, with the rhodopsin dimer most likely being the signaling unit.

Synthesis of the seven-transmembrane apoprotein portion of rhodopsin, called opsin, begins in the inner segments of photoreceptors, where it undergoes maturation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and Golgi membranes before it is transported vectorially to the ROS. The C-terminal region of the protein is essential for interaction with the transport machinery that delivers the cargo of transmembrane- and membrane-associated proteins on membrane vesicles to the ROS (38–40). Specifically, the C-terminal-sorting motif of rhodopsin binds to the small GTPase ARF4, a member of the ARF family of membrane-budding and protein-sorting regulators (41), whereas the sorting protein rab8 is implicated in docking of post-Golgi membranes containing rhodopsin in rods (42). The transport of a rhodopsin mutant lacking the C-terminal region to the ROS does not occur in vivo, and the mutant is piggybacked to the ROS only in the presence of wild-type rhodopsin (43, 44). The regeneration of rhodopsin from opsin and its chromophore 11-cis-retinal is not essential for vectorial transport to the ROS, as mice deficient in chromophore production still develop ROS (45, 46). However, because of the continuous coupling of opsin with G proteins, these rods slowly degenerate (47–51).

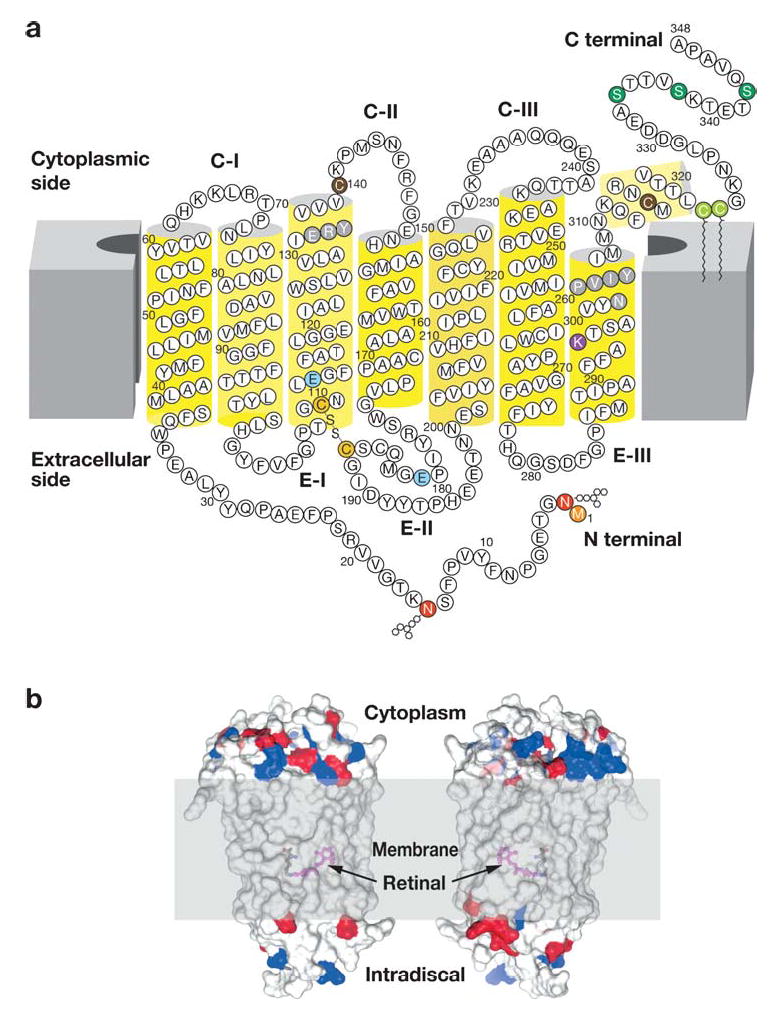

On the basis of the predicted structure, conservation of few amino acids in the region critical for G protein activation, and activation by small ligand, rhodopsin belongs to the largest subfamily of GPCRs (family A) (10). More than a century of extensive biochemical, biophysical, and structural information collected on rhodopsin has given rise to its status as a prototypical receptor of this family. Several efficient methods were developed to isolate rhodopsin, including selective extraction from the ROS in the presence of divalent metal ions (52, 53) and immunoaffinity chromatography (54) (summarized in Reference 6). Bovine retina is an extraordinary source of native protein that yields ~0.7 mg rhodopsin per retina (16). Bovine rhodopsin consists of a 348-amino acid apoprotein opsin and 11-cis-retinal, which is bound to the protein through a Schiff-base linkage to a Lys296 side chain ( Figure 2a,b). Protein posttranslational modifications include double palmitoylation, acetylation of the N terminus, glycosylation with two (Man)3(GlcNAc)3 groups via two asparagine residues, and a disulfide bond ( Figure 2a). In addition, rhodopsin undergoes a light-dependent phosphorylation at one or a few of the six to seven Ser/Thr residues at the C-terminal region (reviewed in 55).

Figure 2.

Modification of rhodopsin molecule and orientation in the membranes. (a) Two-dimensional model of rhodopsin. The polypeptide of rhodopsin crosses the membrane seven times. C-I, C-II, and C-III correspond to the cytoplasmic loops, and E-I, E-II, and E-III correspond to extracellular loops. The transmembrane segment is α-helical ( yellow cylinders), although the helices are highly distorted and tilted. The stability of the helical segment is increased by the Cys110-Cys187 bridge (141) (depicted in dark yellow) a highly conserved feature among many GPCRs. The chromophore, 11-cis-retinal, not depicted here, is attached to Lys296 (dark red ) via a protonated Schiff base. The positive charge of the base is neutralized by counterion Glu113 (blue). During postisomerization changes in the receptor, it was proposed that the counterion migrates to Glu181 (blue) (76). Asn2 and Asn15 (red ) are sites of glycosylation within the conserved glycan composition, and Met1 (orange) is acetylated. Cys322 and Cys323 (light green) are palmitoylated, whereas two other Cys, Cys140 and Cys316 (brown), are reactive to many chemical probes and are used to explore rhodopsin’s structure. Rhodopsin, when exposed to light, is phosphorylated by rhodopsin kinase (or G protein–coupled receptor kinase 1). The predominant phosphorylation sites are Ser334, Ser338, and Ser343 (green) (55), and the whole C-terminal region is highly mobile (142). However, as shown using a model peptide, the C-terminal region may become structured when bound to arrestin (143). The highly conserved domains among GPCRs, D(E)RY in helix 3 and NPXXY in helix VII ( gray), are important in transformation of the receptor from an inactive to a G protein–coupled conformation. Different versions of this figure were published previously (for example in 19 and 64), and all of them are refinements of the pioneering work on rhodopsin topology by Paul Hargrave (144, 145). (b) Location of the chromophore and charges on the cytoplasmic and intradiscal (extracellular) surface of rhodopsin in relation to the hypothetical membrane bilayer. The negative charges (red ) and basic residues (blue) are shown. The proposed location of the membrane is shown in gray, and the location of the chromophore 11-cis-retinylidene is shown by deleting fragments of transmembrane helices. Two sides of rhodopsin are depicted.

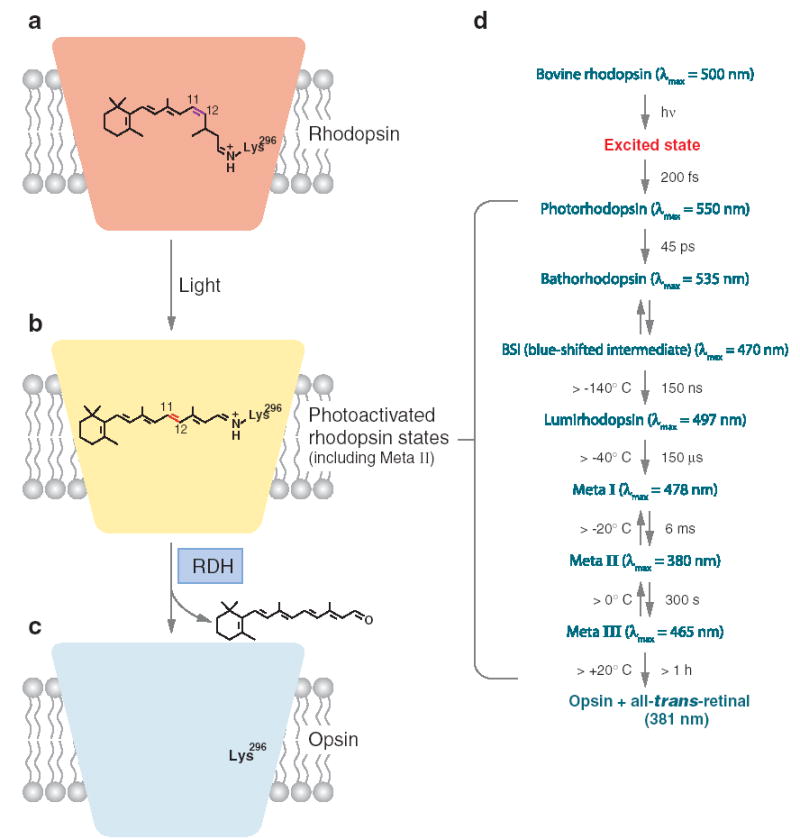

Rhodopsin changes in color upon exposure to light, as described by Kühne (see translations in References 56 and 57; also see the side bar Discovery of Rhodopsin). In ordinary conditions, absorption of a photon of light causes photoisomerization of 11-cis-retinylidene to all-trans-retinylidene, with an accompanying shift in the λmax of absorption bovine rhodopsin from 498 nm to 380 nm ( Figure 3a–c). Ultimately, the Schiff base is hydrolyzed, and all-trans-retinal is reduced by retinol dehydrogenase to all-trans-retinol (reviewed in 15 and 58). The change in the λmax of absorption after the illumination of rhodopsin is a very sensitive parameter, which has been correlated with the receptor conformation in numerous studies ( Figure 3d ). A number of intermediates were trapped at low temperatures, and the equilibrium between slowly formed species of photoisomerized rhodopsin was shown to be affected by ionic strength, pH, glycerol, and temperature ( Figure 3d ). The main conclusions of these spectroscopic studies in conjunction with the current structural understanding of rhodopsin can be summarized as follows:

Figure 3.

Light-cycle of rhodopsin. (a) Rhodopsin and 11-cis-retinal. Rhodopsin consists of a colorless protein moiety (the opsin) and the chromophore, 11-cis-retinylidene, which imparts a red color to rhodopsin. The chromophore, a geometric isomer of vitamin A in aldehyde form, is coupled to opsin via the protonated Schiff base at Lys296, located in the transmembrane domain of the protein. Bovine rhodopsin absorbs at a λmax = 498 nm. (b) Photoactivated rhodopsin. Absorption of light by rhodopsin leads with high probability (~65%) to photoisomerization of the cis C11-C12 chromophore double bond to a trans configuration. The probability of isomerization depends only modestly on the wavelength of the light (146). This reaction, one of the fastest photochemical reactions known in biology, produces multiple intermediates that culminate in the formation of the G protein–activating state, termed metarhodopsin II, or Meta II. (c) Opsin without chromophore. Ultimately the photoisomerized chromophore, all-trans-retinylidene, is released from the opsin as all-trans-retinal and reduced to alcohol by short-chain alcohol dehydrogenases, such as prRDH, retSDR, and RDH12. The all-trans chromophore diffuses to the adjacent retinal pigment epithelium, where it undergoes enzymatic transformation back to 11-cis-retinal in a metabolic pathway known as the retinoid cycle. Opsin recombines with replenished 11-cis-retinal to form rhodopsin. (d ) Reaction scheme of rhodopsin photoactivation. Upon absorption of a photon by rhodopsin and electronic excitation, fast isomerization of 11-cis-retinylidene to all-trans-retinylidene takes place. At body temperature, the Meta I and Meta II exist in equilibrium shifted toward Meta II. In vitro, further decay of rhodopsin to both opsin and free all-trans-retinal or to Meta III is possible. In vivo, Meta III is not formed at significant levels because it decomposes in the presence of G protein transducin (147). In vitro, prolonged incubation of Meta II involves a thermal isomerization of the chromophore double bond with Lys296 to an all-trans-15-syn configuration. This isomerization step is catalyzed by the opsin itself (148). On the left are maximal temperatures at which indicated intermediates can be trapped, and on the right is time required for that particular transformation. In the brackets are λmax of absorption for different intermediates. The reaction scheme is based on Shichida & Imai [(149); see also the thermodynamic properties of these reactions (19)].

Prior to any change in protein conformation, the energy of the photon is stored by the chromophore in its highly distorted all-trans-retinylidene form in the same binding pocket where it resides in the dark state as 11-cis-retinylidene. Rohring et al. (60) suggested that the protein-binding pocket selects and accelerates the isomerization exclusively around the C11-C12 bond, resulting in the formation of a twisted structure; “hence, the initial step of vision can be viewed as the compression of a molecular spring that can then release its strain by altering the protein environment in a highly specific manner” (60).

Photoisomerization is ultrafast and occurs within 200 femtoseconds (59).

Meta I is transiently formed and decays to Meta II (19).

Meta II is the heterogeneous form of several photoactivated conformations (61). This physiologically important intermediate of rhodopsin is responsible for interaction with peripheral membrane proteins, including the heterotrimeric G protein transducin.

Opsin spontaneously combines with 11-cis-retinal chromophore to regenerate rhodopsin. In contrast with opsin, rhodopsin has no basal activity toward the G protein transducin. The rapid transformation of opsin to rhodopsin terminates signaling activity, allowing the rod cells to maintain a low activation threshold. The extraordinary sensitivity of rods is illustrated by the photoactivation of 1 to 10,000 rhodopsin molecules out of the ~8 × 107 per rod. A single photon is sufficient to consistently generate a measurable response. As mentioned above, in cases when opsin fails to reunite with the chromophore to regenerate rhodopsin, the persistent activation of G proteins by opsin destabilizes and eventually damages the rod cell (40–44). As a note of interest, rhodopsin in the lancelet Branchiostoma is regenerated by the agonist all-trans-retinal as well as by 11-cis-retinal, suggesting that the structures of opsin and rhodopsin are similar (62, 63).

DISCOVERY OF RHODOPSIN

The reddish-purple coloration of rod cells was noted in 1851 by Heinrich Müller, who attributed it to hemoglobin. In 1876, Franz Boll recognized that frog retina is photosensitive and when exposed to light, the pigment bleached to a yellowish color and then became colorless. Boll demonstrated that frogs exposed to sunlight and then kept in darkness regenerated the red pigment. After many observations, he concluded, “The basic color of the retina is constantly consumed in vivo by the light falling on the eye…. In the dark, in vivo, the color is regenerated.” Willy Kühne, pursuing Boll’s findings, determined the pigmented material to be a rod outer segment protein he named “visual purple” (rhodopsin). Kühne isolated frog retinas and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) layers in experiments, proving that the RPE is necessary for the regeneration of rhodopsin. He extracted rhodopsin using bile salts, matched its spectral absorption profile to that of dissected retinas, proposed that the yellow and colorless products of bleaching must be chemically distinct substances, and correlated the electrical impulses emitted by isolated retinas to their illumination. Kühne’s extensive investigation of the visual system began to elucidate the now-familiar story of a photochemical reaction whose products stimulate nerve impulses to the brain.

OVERVIEW OF THE RHODOPSIN STRUCTURE

The structure of rhodopsin is only briefly described because the specific structural features of the receptor were described fully in the original research (20, 64–67) and previous review publications (16, 18, 19). The overall elliptic, cylindrical shape of the rhodopsin molecule is due to arrangement of its seven transmembrane helices, which vary in length from 20 to 33 residues ( Figure 2a,b). The N-terminal region is located intradiscally (extracellularly) ( Figures 1d and 2a,b), and the C-terminal region is cytoplasmic. The dimensions of rhodopsin, described by a ellipsoid, are ~75 Å perpendicular to the membrane, ~48 Å wide in the standard view, and ~35 Å thick. The surface area of the portions projecting from the membrane is ~1200 Å2, with the cytoplasmic projection larger in volume and surface area than the intradiscal face ( Figure 2b). The distribution of mass for the intra- and extracellular regions is comparable, whereas the transmembrane region encompasses ~65% of the amino acids. The chromophore is located within this hydrophobic transmembrane core (Figure 2b; see also the Chromophore side bar).

The transmembrane helices are irregular, particularly with respect to the degree of bending around Gly–Pro residues, and they tilt at various angles with respect to the expected membrane surface, as described elsewhere (20, 64). The strongest distortion is imposed by Pro267 in helix VI, one of the most conserved residues among the GPCRs. The presence of Pro291 and Pro303 in the region around the retinal attachment site Lys296 elongates helix VII. Pro303 is a part of the NPXXY (AsnProXaaXaaTyr) motif located at the end of helix VII and the beginning of helix 8. A high-affinity Zn2+ coordination site has been identified within the transmembrane domain of rhodopsin, coordinated by the side chains of two highly conserved residues, Glu122 of helix III and His211 of helix V (68). It is not clear whether (or there is no evidence one way or the other to support the conclusion that) the ability of rhodosin to bind Zn2+ in vitro reflects a physiologically relevant role for this divalent cation in rhodopsin function in vivo. In detergent solutions, Zn2+ lowers the stability of rhodopsin and the extent of rhodopsin regeneration (69).

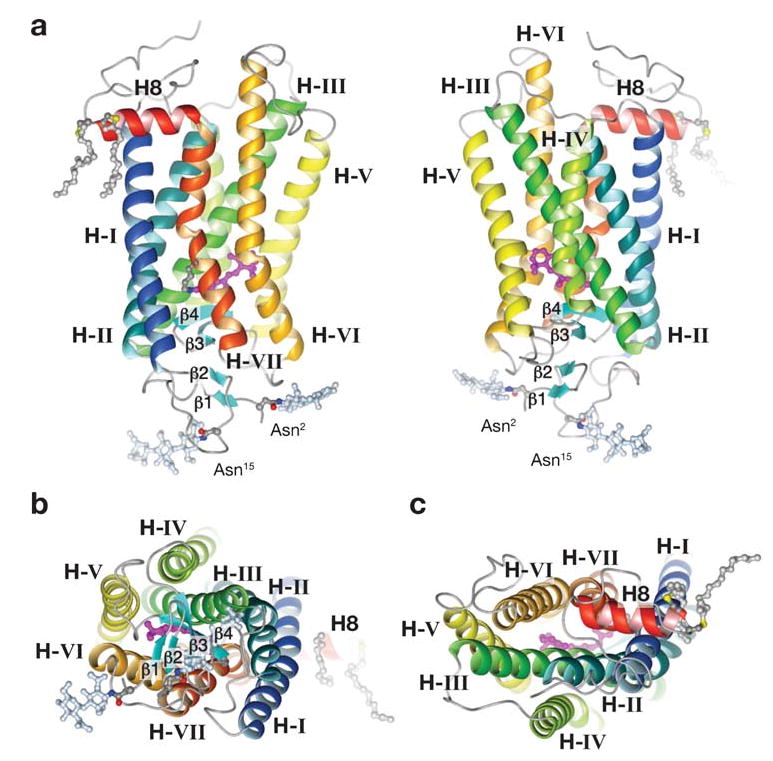

The extracellular (intradiscal) and intracellular regions of rhodopsin each consist of three interhelical loop and a terminal tail regions. Bourne & Meng (70) describe the extracellular N-terminal domain as a “plug” for the chromophore-binding pocket ( Figure 4b). This globular domain is formed by residues 1 to 33, the short loop of residues 101–105, “plug” residues 173–198 between helices IV and V, and residues 277–285 between helices VI and VII ( Figure 2a). The Asn2 and Asn15 residues are the glycosylation acceptor sites for GlcNAc-(β1,4)-GlcNAc-(β1,4)-mannose ( Figures 2a and 4a). There are four extracellular structural elements associated significantly with each other (pairs of β1-β2 and β3-β4 hairpins) ( Figure 4b). The extracellular loop II is connected to helix III via a disulfide bridge and fits tightly into a limited space inside the bundle of helices. A detailed description of the region can be found in References 16, 20, 64, and 67.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional model of rhodopsin. (a) Ribbon drawings of rhodopsin parallel to the plane of the membrane. (b) View into the membrane plane as seen from the intradiscal side of the membrane. The carbohydrate moieties are at Asn2 and Asn15. The pairs of β1-β2 and β3-β4 hairpins, the transmembrane helices (Hs) I–VII, and the cytoplasmic helix 8 (H8) are labeled. A palmitoyl group is attached to each of the two Cys residues at the end of helix 8. The removal of the palmitoyl groups has only a minor effect on phototransduction processes (e.g., 150 and 151). (c) A view into the membrane plane as seen from the cytoplasmic side. The cytoplasmic side has greater surface area than the intradiscal side. (The roman numeral convention is related to transmembrane helices, whereas an Arabic numeral indicates a solvent-exposed helix.)

The cytoplasmic side includes the three loops, located between helices, encompassing residues Gln64-Pro71, Glu134-His152, and Gln225-Arg252; the peripheral helix 8; and the C-terminal tail. The residues of a highly conserved (D/E)R(Y/W) motif, found in GPCR subfamily A, are formed by the tripeptide Glu134-Arg135-Tyr136 located in this region (10) ( Figure 2a). The carboxylate of Glu134 forms a salt bridge with Arg135, whereas Arg135 also interacts with Glu247 and Thr251 in helix VI. The ionization state of Glu134 is sensitive to its environment, and when this residue is protonated, rhodopsin could become activated (71). Val137, Val138, and Val139 are also located close together and partially cover the cytoplasmic side of Glu134 and Arg135. This region is likely to be a critical constraint, which keeps rhodopsin in the inactive conformation. Cytoplasmic helix 8 (residues 311–321), structurally similar in all crystal forms, is fastened to the membrane by the palmitoylation of residues Cys322 and Cys323. The helix VII/helix 8 kink is stabilized by residues Glu249 to Met309, Asn310 to Phe313, and Arg314 to Ile307, and helix 8 is further stabilized by hydrophobic side chain residues buried within the hydrophobic residues of the transmembrane domain located in helices I and VII ( Figure 4c). Another region conserved among GPCRs and located close to helix 8 is the NPXXY sequence (NPVIY in rhodopsin) near the cytoplasmic end (10), which is likely to be involved in G protein coupling (72) ( Figure 2a). The side chains of the two polar residues in this region, Asn302 and Tyr306 in bovine rhodopsin, project toward the transmembrane core of the protein and Phe313, respectively, in helix 8. The -OH group of Tyr306 is close to Asn73 and is engaged in the interhelical hydrogen-bonding constraints between helix VII and helix II. These interactions most likely occur through water molecules.

CHROMOPHORE OF RHODOPSIN

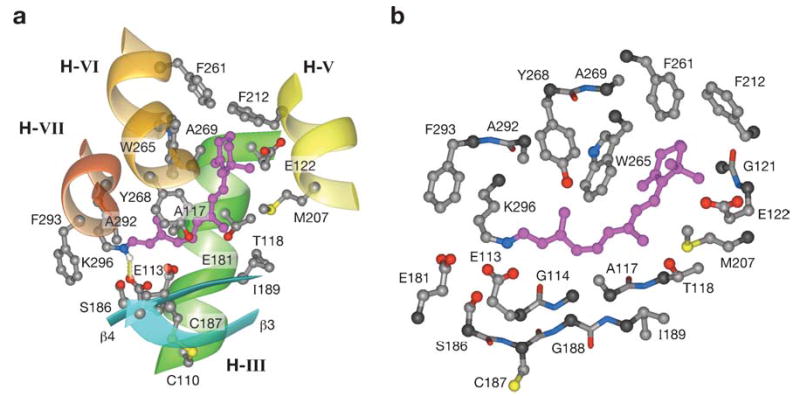

Rhodopsin of the rod cell and other visual pigments of the cone cells contain the 11-cis-retinal chromophore, bound via a protonated Schiff-base linkage to a Lys side chain (Lys296 in bovine rhodopsin) in the middle of helix VII ( Figures 2a, 4). The interaction between the protein moiety and the chromophore produces a specific absorption shift for visual pigments compared with the retinal protonated Schiff-base model compounds formed between alkylamines and retinal, which absorb light maximally at ~440 nm. In addition to the retinal cavity formed by helices of the transmembrane segment, an antiparallel β sheet of the plug, the part of extracellular loop II that includes Glu181, penetrates deep into rhodopsin’s interior, close to the chromophore. The retinylidene moiety is located closer to the extracellular side in the hypothetical lipid bilayer ( Figure 2b). The counterion for the protonated Schiff base is provided by Glu113, which is highly conserved among all known vertebrate visual pigments. Kim et al. (73) reported that this salt bridge, formed between a protonated Schiff base and Glu113, is a key constraint in maintaining the resting state of the receptor and that disruption of the salt bridge is the cause, rather than a consequence, of the helix VI motion that occurs upon photoactivation. The counterion has two other important functions: (a) It stabilizes the protonated Schiff base by increasing the Ka for this group by as much as 107, thus preventing its spontaneous hydrolysis (reviewed in 74); and (b) it causes a bathochromic shift in the maximum absorption for visual pigments, which makes them more sensitive to longer wavelengths because UV light is filtered out by the front of the eye in most animals. The 11-cis-retinylidene group is surrounded by the 20 residues depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The amino acid residues in the vicinity of the chromophore. (a) Schematic showing the side chains surrounding the 11-cis-retinylidene group ( pink); side view through helices III, V, and VI. (b) Schematic presenting the residues within 5 Å distance from the 11-cis-retinylidene group ( pink). Note that the chromophore is coupled via the protonated Schiff base with Lys296.

The energy of a photon enables protein conformational changes that culminate in the formation of active Meta II, which can be considered analogous to the agonist-bound state of many ligand-binding GPCRs. Recently, Ernst and colleagues (75) demonstrated that cis acyclic retinals, lacking four carbon atoms of the β-ionone ring, can only partially activate rhodopsin when photoisomerized. Detailed analysis of rhodopsin regenerated with these acyclic retinals revealed that a lack of the ring structure destabilizes the active state. This study describes for the first time the molecular mechanism of activation by a partial agonist, a mechanism that possibly extends to other GPCRs. The partial agonism is due to instability of the only partially active state of the receptor.

CHROMOPHORE

George Wald and his Harvard colleagues were the first to reveal that rhodopsin contains two distinct components, a colorless protein termed opsin and a yellow pigment, 11-cis-retinal, that serves as its chromophore. In 1933, following a hunch that rhodopsin might contain a carotenoid, Wald isolated vitamin A from retinal tissue, a finding consistent with literature linking night blindness with vitamin A deficiency. At the time, little was known about the biochemical roles played by vitamins. Using frog retinal extracts in fat solvents, Wald proceeded to show that rhodopsin and its orange bleached intermediate both released a yellow material he termed retinene, which was then replaced by vitamin A as the purplish retinal color faded. Retinene (retinal) proved to be vitamin A aldehyde and could be mixed in the dark with bleached rhodopsin or with opsin to regenerate fresh rhodopsin. Wald’s team later showed that only the bent 11-cis-isomer combined with opsin to form rhodopsin. Wald received the 1967 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for characterizing the molecular components of vision and discovering the biochemical role for vitamin A.

RECENT STRUCTURAL DATA ON RHODOPSIN

Progress continues in further refining the structure of rhodopsin and obtaining new details of intermediate photobleaching states. Okada and colleagues (66) investigated the functional role of water molecules in the transmembrane regions of bovine rhodopsin. They successfully improved the original rhodopsin crystals, increasing their resolution to 2.6 Å. This improvement led to unambiguous differentiation between water molecules and Zn2+ used for rhodopsin purification. Seven water molecules were found in the transmembrane segment. The cluster 1 containing water molecules 1a, 1b, and 1c is linked to Asn302 and Asp83 in helix II and a residue of the NPXXY motif of the helix VII. The second cluster, containing water molecules 2a and 2b, is located in the vicinity of the retinal Schiff base. Water molecule 2a is located between the side chains of Glu181 and Ser186 in the vicinity of the counterion Glu113. Water molecule 2a may play a key role in transferring the counterion from Glu113 in rhodopsin to Glu181 in Meta I (76) ( Figure 5a,b). A similar switch of counterions was proposed for the UV visual pigment (77). Water molecule 3 is surrounded by the peptide main chains of helices VI and VII, and water molecule 4 facilitates interaction between helices I and II at the cytoplasmic surface. It is expected that water molecules play a key role in visual pigment spectra sensitivity (response to a specific wavelength of light), conformational changes during activation, and transmission of the signal from the photoisomerized chromophore to the D(E)RY and NPXXY regions on the cytoplasmic surface of rhodopsin during photoactivation (for example 19 and 20). In invertebrate rhodopsin, the counterion of the Schiff base is a residue, which corresponds to Glu181 (78), the proposed counterion of Meta I in vertebrate rhodopsin (76).

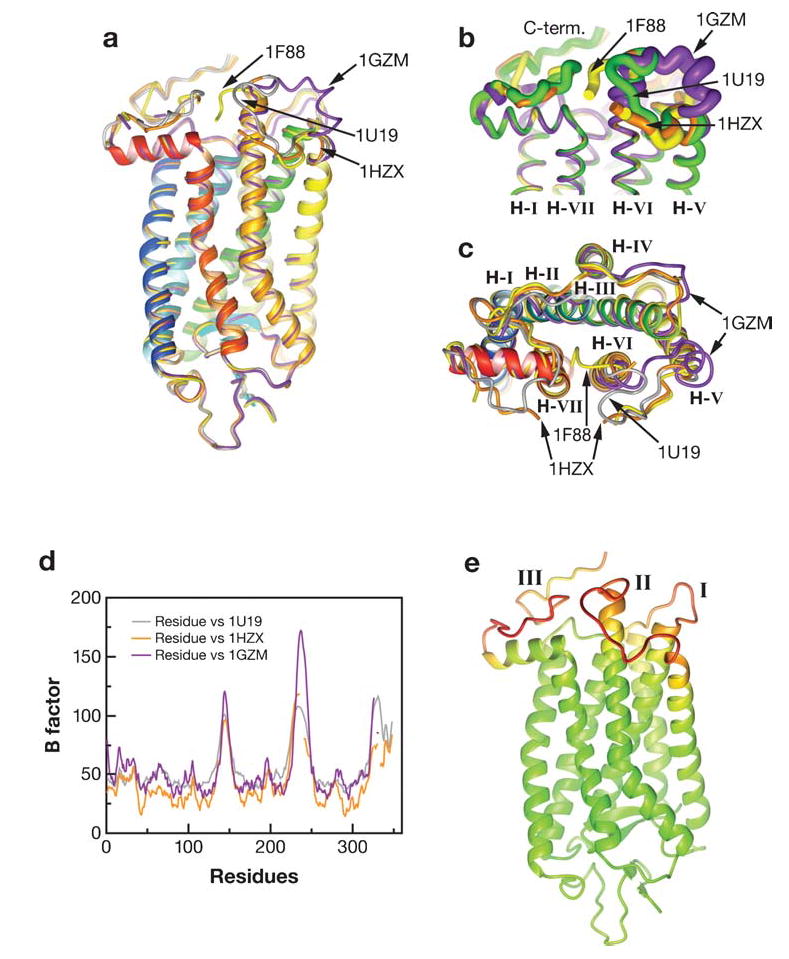

A major contribution to our understanding of how rhodopsin works at the molecular level was made by the Schertler laboratory. Krebs et al. (79), using electron cryomicroscopy of two-dimensional crystals with p22121 symmetry, produced a rhodopsin map with a resolution of 5.5 Å in the membrane plane and 13 Å perpendicular to the membrane, obtaining information about the orientation of the molecule relative to the bilayer. Li et al. (67) generated new three-dimensional crystals of highly purified rhodopsin, using C8E4 (n-octyltetraoxyethylene) and LDAO (N,N-dimethyldodecylamine-N-oxide) detergents with Li2SO4 and PEG 800 as precipitants. The crystals belong to the trigonal space group P31 and diffract to 2.55 Å. The rhodopsin structure has been determined using data obtained from these crystals (67). As in the previous studies, ordered water molecules were found, for example, linking Trp265 in the retinal-binding pocket to the NPXXY motif and stabilizing the Glu113 counterion with the protonated Schiff base at the extracellular surface. The cytoplasmic ends of helix V and helix VI are extended by one turn, distinguishing this structure from ones previously determined ( Figure 6a–c). However, the cytoplasmic loops have the highest temperature factor (B factor), a measure of certainty of a location of an atom within the crystal structure, in all crystal structures ( Figure 6d,e), suggesting flexibility in this region in addition to the possibility of a crystal-packing artifact. Ruprecht and coworkers (80) used electron crystallography to determine a density map of Meta I to a resolution of 5.5 Å in the membrane plane, and this suggested that Meta I formation does not involve large helical movements. They provided some evidence that the changes in Meta I involve a rearrangement close to the bend of helix VI in the vicinity of the chromophore-binding pocket. The spectra of these crystals studied with Fourier transform infrared difference spectroscopy revealed that the formation of the active state, Meta II, is blocked in the crystalline environment, as indicated by a lack of spectral features in Meta II and a lack of activation of the G protein transducin (81).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the current rhodopsin structures. There are currently five crystallographic entries for rhodopsin in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The structures deposited under the accession number 1F88, 1HZX, 1GZM, and 1U19 are superimposed. Accession number 1F88 ( yellow thread), 1HZX (orange), 1GZM ( purple), and 1U19 ( gray) are represented in the cartoon. Entries 1F88, 1HZX, 1L9H, and 1U19 are for a tetragonal crystal obtained by very similar methods. Entry 1U19 is at the highest resolution reported, 2.2 Å. Entry 1GZM is for a trigonal crystal form obtained in a different condition than the other listed crystals. (a) Side view. (b) Side view, with a close-up of the cytoplasmic region. (c) View from the cytoplasmic side. (d,e) A plot (d ) and three-dimensional representation (e) of the B factor for rhodopsin structures from three data sets. The B factor is also known as the temperature factor or Debye-Waller factor and describes the degree to which the electron density is spread out, indicating the static or dynamic mobility of an atom or incorrectly built models. In panel d, the orange line represents 1HZX, the purple line represents 1GZM, and the gray line represents 1U19. In panel e, spectral grading of the B factor, green represents a low B factor, and red indicates the highest B factor. Note that the loop II is incomplete in 1HZX because of ambiguity in the electron density, and this region in the 1GZM set has the highest B factor.

Buss and colleagues (65) used a theoretical study of the chromophore geometry in combination with rhodopsin crystals that diffracted to 2.2 Å to focus on the conformation of the chromophore, providing new insight into the twist of the 6-s-cis-bond and the C11-C12 double bond (65). The comparison of these structures is depicted in Figure 6a–c. The panels in this figure reveal differences in the structure only at the flexible cytoplasmic region of rhodopsin ( Figure 6b,c), characterized by large B factors ( Figure 6d,e).

Creemers and colleagues (82) determined the complete 1H and 13C assignments of the 11-cis-retinylidene chromophore in its ligand-binding site using ultra-high field magic-angle-spinning NMR. A gallant synthesis of 99% enriched uniformly 13C-labeled 11-cis-retinal by Lugtenburg’s laboratory made this work possible (83). Authors found interactions between the chromophore’s H16/H17 and Phe208, Phe212, and H18 to be in close contact with Trp265. This NMR study revealed that binding of the chromophore involves a chiral selection of the ring conformation, resulting in equatorial and axial positions for CH3-16 and CH3-17 (82).

High-resolution solid-state NMR studies of the Meta I photointermediate are in agreement with the electron microscopy data (84). The β-ionone ring retains strong contacts in its binding pocket prior to activation of the receptor without any major protein rearrangements around the chromophore-binding site. Further studies reveal an increase in steric clashes and an adjustment of the protein structure in Meta II, without substantial changes in the location of the all-trans-retinylidene chromophore (85). These results are at odds with another NMR study and biochemical studies that predict changes in the location of the chromophore during transition to Meta II (86, 87).

Patel et al. (88), using solid-state magic-angle-spinning NMR spectroscopy, found that Trp126 and Trp265 become more weakly hydrogen bonded during the transformation of rhodopsin to Meta II and that both the side chain of Glu122 and the backbone carbonyl of His211 are disrupted in Meta II. Clearly, the full picture of rhodopsin transition from an inactive to active state will require a high-resolution structure of Meta II obtained by X-ray crystallography.

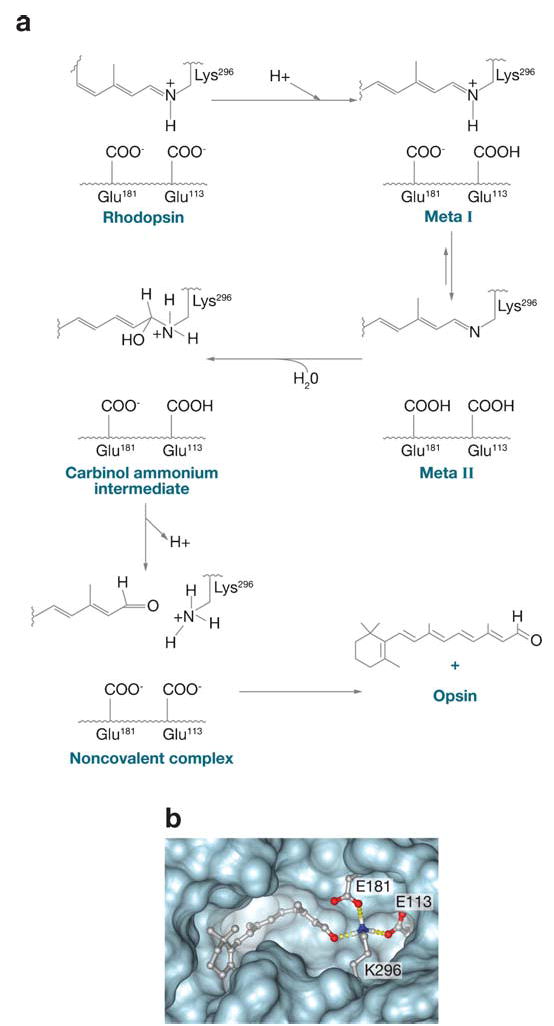

The isomerization of 11-cis-retinylidene is followed by hydrolysis of the photobleached product all-trans-retinylidene and the subsequent release of all-trans-retinal from the binding pocket ( Figure 3a–c). The rapid regeneration and recombination of 11-cis-retinal with opsin restores dark conditions to permit subsequent photon absorption, allowing our vision to work in an uninterrupted manner. Perhaps the same key residues involved in isomerization are involved in the hydrolysis process, such as Glu113 and Glu181 via the carbinol ammonium ion ( Figure 7a), and in a coupling reaction between 11-cis-retinal and opsin ( Figure 7b). To form the Schiff base, Lys296 must be deprotonated, the carbonyl group must be polarized, and water excluded or organized in the chromophore-binding site. This mechanism or alternative proposals require rigorous experimental analysis to reveal the correct mechanism.

Figure 7.

Hydrolysis of the all-trans-retinylidene chromophore and regeneration of rhodopsin with newly synthesized 11-cis-retinal. (a) The scheme of the retinylidene group hydrolysis. The role of Glu181 and Glu113 is hypothetical. Note that Glu181 is protonated in rhodopsin (71). (b) Formation of rhodopsin. Polarization of the carbonyl group of 11-cis-retinal and deprotonation of the Schiff-base group is required before the Schiff base can be formed.

Another challenging question in studies of the rhodopsin cycle is how the chromophore inserts in and out of the binding pocket. Hofmann and colleagues (89) proposed that, in addition to the retinylidene pocket (site I), there are two other retinoid-binding sites within opsin. Site II is an entrance site to the binding site involved in the uptake signal, and the exit site (site III) is occupied when retinal remains bound after its release from site I. This chromophore-channeling mechanism, movement of the chromophore from one to another site in a sequential way, is supported by the rhodopsin crystal structure, which unveiled two putative hydrophobic-binding sites. Importantly, this proposed mechanism enables a unidirectional process for the release of a photoisomerized chromophore and the uptake of newly synthesized 11-cis-retinal for the regeneration of rhodopsin. Arrestin, the capping protein that binds to activated phosphorylated rhodopsin and blocks G protein (transducin) activation, may play an important role in chromophore release. Farrens and colleagues (90) showed that arrestin and all-trans-retinal release are linked and require similar activation energies.

DIMERIZATION OF RHODOPSIN

Rhodopsin has been visualized in the native disk membranes by atomic force microscopy and transmission electron microscopy under various temperatures and other conditions (91–93). Rhodopsin was found to form rows of dimers containing densely organized higher-order structures. Moreover, native and denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, chemical cross-linking, and proteolysis experiments corroborated that rhodopsin consists mainly of dimers and higher oligomers in disk membranes (94, 95). Rhodopsin dimerization was also observed by luminescence and fluorescence resonance energy transfer approaches, using fluorescently labeled rhodopsin samples in an asolectin liposome-reconstituted system (S.E. Mansoor, K. Palczewski, and D.L. Farrens, unpublished findings). Medina and colleagues (91) reported that rhodopsin and photoactivated rhodopsin retained a dimeric quaternary structure in n-dodecyl-β-maltoside. Jastrzebska et al. (95) found also that the dimeric structure is preserved in low concentrations of this detergent. Understandably, static techniques such as atomic force microscopy and transmission electron microscopy may not reflect the kinetic aspects of formation and disassembly of these higher-order structures.

Reconstitution of rhodopsin into two-dimensional crystals produces dimers where both rhodopsin molecules are correctly oriented, but the dimers contact other dimers that are rotated 180° along their long axis in their orientation (for example, see 79–81). The dimerization of rhodopsin can explain the autosomal dominant character of rhodopsin mutants, e.g., P23H rhodopsin. A cell line expressing P23H mutant rhodopsin retains both the mutant and wild-type proteins in intracellular inclusion bodies (109).

In a first approximation, these results are in conflict with a model of rapidly diffusing and rotating rhodopsin in homogenous fluid disk membranes and lack of any symmetry within ROS as determined by low-resolution neutron diffraction (96–100). In addition, the concept of rapidly diffusing monomeric molecules is also at variance with the dimeric forms of other GPCRs (101, 102), although diffusible dimers could be compatible with these recent structural and biochemical results and earlier biophysical measurements. Oligomerization of GPCRs has been a very active research area recently (102–107), resulting in strong evidence that the higher-order structures play a central role in GPCR signal transduction and desensitization (108).

INTERACTION OF RHODOPSIN WITH G PROTEIN

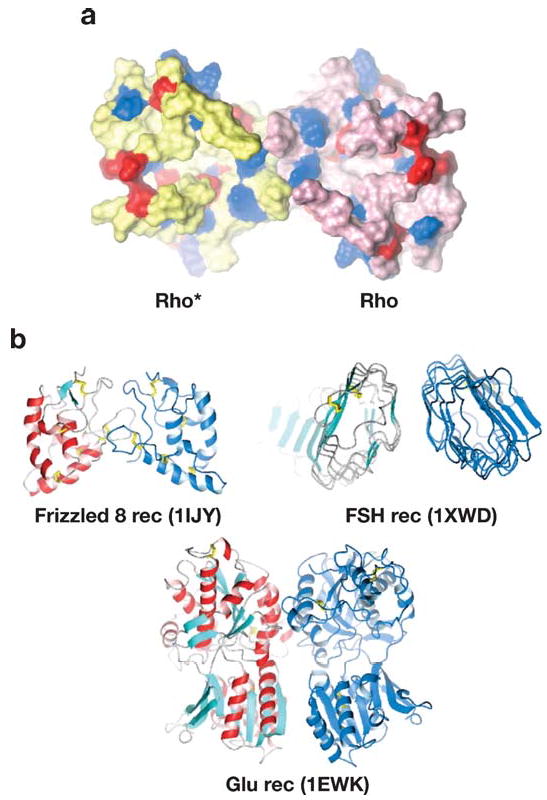

A model was generated for the interaction of photoactivated rhodopsin with G protein (110). This model, the so-called IV-V arrangement of rhodopsin in the membranes ( Figure 8a), is based on a structure of rhodopsin determined from X-ray crystallography and on the dimensions of rhodopsin found by atomic force microscopy in the native ROS membrane (111). The model proposes that rhodopsin molecules in the dimer contact each other via transmembrane helices IV-V. Activation of the dimer is accompanied by changes within helix VI and the NPXXY region of only one rhodopsin molecule within the dimer (72). Particularly interesting is the interaction model of photoactivated rhodopsin with transducin. This model of G protein activation considers the size of partner proteins, structural constraints, and organization of GPCRs in the membranes. The N- and C-terminal regions of transducin’s α-subunit are engaged in the interaction with photoactivated rhodopsin (112–114). Only a narrow region of transducin containing hydrophobic posttranslational modification of α- (myristoylation) and γ-subunits (farnesylation) anchors this protein to the membrane, and the remaining protein surface is available to interact with rhodopsin molecules (115). The C-terminal tail binds to the inner face of helix VI in an activation-dependent manner (114) in a configuration (116), consistent with our model. This model, for which a short movie is available (106), reveals structural details about the critically important interface between a GPCR and a G protein. The IV-V model suggests that the view of GPCR signaling of oligomers of G protein and the receptors put forward by Rodbell (117, 118) are consistent with the structural evidence. Although not every detail may withstand experimental scrutiny, the general concept is probably correct. Our model is in substantial agreement with the transactivation of family A GPCRs, employing fusion proteins between active and inactive receptors and G proteins (119) and the identified pentameric complex between dimeric leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and heterotrimeric Gi (120). The studies on the chimeric rhodopsin/β2-adrenergic receptor clearly confirm that specificity for G proteins is confined to the cytoplasmic surface. In the chimera, the surface of rhodopsin or β2-adrenergic receptor undergoes changes as a result of chromophore isomerization and recruits the G protein (121). These studies are reminiscent of the innovative and insightful work of Kobilka et al. on chimeras of adrenergic receptors (122), which led to the identification of major determinants of ligand and G protein specificities.

Figure 8.

Models of GPCR dimerization. (a) Top view from the cytoplasmic side of the rhodopsin dimer. The model was generated by Dr. S. Filipek using structural constraints of rhodopsin and experimental data obtained by atomic force microscopy on the organization of rhodopsin in native membranes (33, 92, 93, 110, 111). This model is in agreement with cross-linking experiments (94). Photoactivated rhodopsin is depicted in yellow (Rho*), and rhodopsin is shown in pink. The acidic residues are shown in red and basic residues in blue. This cytoplasmic surface is involved in the interaction with G protein transducin. (b) The crystal structures of extracellular domains of different GPCRs. Crystal structures of the extracellular domains of the frizzled 8 receptor, the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor, and the Glu receptor revealed that the extracellular domains formed a dimer. These structures may represent a physiological dimer that would stabilize the transmembrane domain and result in a dimeric platform for interaction with G proteins and other partner proteins. Protein Data Bank accession numbers are shown in parentheses. Panels a and b are not drawn to the same scale.

CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Studies on rhodopsin continue at a rapid pace, as is evident in this account of recent progress. The key questions that require further investigation include the following:

What are the changes in structure that transform rhodopsin from its inactive to active conformation capable of interacting with partner proteins?

What are the structures of complexes between photoactivated rhodopsin and G protein transducin, and between a photoactivated phosphorylated monomer or dimer of rhodopsin and arrestin or its spliced form, p44?

What is the role of GPCR dimerization in signaling and desensitization?

What is the mechanism of all-trans-retinal’s release from opsin and regeneration of rhodopsin with 11-cis-retinal?

How does the cell transport and degradation of rhodopsin?

This is an ambitious set of goals that will keep rhodopsin studies at the cutting edge of GPCR research.

An image of the photoactivated structure of rhodopsin appears to be achievable by X-ray crystallography. The question that will inevitably need to be answered is whether this crystal structure will accurately reflect the conformation of photoactivated rhodopsin in membranes. Possibly, activated rhodopsin forms a constellation of conformations (106). Obtaining a high-resolution structure of the complexes between rhodopsin and its partner proteins transducin and arrestin is a paramount challenge, but it will yield major insight into how rhodopsin and other GPCRs work. What is the role of rhodopsin dimerization during signaling, biosynthesis in ER and ROS formation, and degradation? Dimerization of rhodopsin, like other GPCRs, may positively or negatively modulate G protein coupling (see for example 106 and 123). Because of the transient nature of the photoactivated rhodopsin-rhodopsin kinase complex, an image of this complex will be achieved when breakthroughs in biochemical techniques allow stabilization of the complex.

Great progress is anticipated in understanding the mechanism of rhodopsin regeneration and photoisomerized chromophore release. The methodology is well developed (e.g., see 89, 124, and 125), and fast kinetic recording devices are available. Activation of a single rhodopsin molecule reliably triggers the enzymatic events of the phototransduction pathway. A precise structure and kinetic base model of a single molecular event is needed. Moreover, at such low bleaches, a specific tunneling of the chromophore from one binding site to another must take place in order for it to be reduced by dehydrogenase, or for 11-cis-retinal to locate and bind to bleached opsin if the regeneration takes place under such conditions. The dehydrogenase responsible for reduction of all-trans-retinal is under investigation (e.g., see 126 for recent discussion).

The way in which the transmembrane core and extracellular plug structure of rhodopsin is held together will provide clues as to why so many mutations in this region cause rod degeneration (127). Some of these mutations may cause problems with membrane insertion or with maturation of rhodopsin during biosynthesis, and some may lead to opsin instability or to novel conformations. For example, the Thr4Arg mutation destabilizes opsin (128), causing light-dependent degeneration of the retina (129), and the Thr94Ile mutation is linked to thermal instability (130). Interestingly, a pharmacological chaperone may stabilize mutant proteins (131–133), a phenomenon which must be explored further in animal models of retinitis pigmentosa. Opsin unfolding can be studied by atomic force spectroscopy, as was exemplified for bacteriorhodopsin (134).

The biological lifetime of rhodopsin was previously impossible to study because rod cells, which are postmitotic neurons, cannot be cultured while maintaining the proper morphology of a tight link between photoreceptors and the adjacent retinal pigment epithelium, essential for their functioning (12). These problems have now been overcome by two major technical innovations, in vivo two-photon fluorescent microscopy, which can noninvasively penetrate the sclera of the eye (135, 136), and genetically engineered mice (137). Green fluorescent protein-tagged rhodopsin can be now traced in truly in vivo conditions.

Progress in structure determination of the extracellular domain of several GPCRs ( Figure 8b) illustrates that, although the general topology of GPCRs is conserved, the extracellular domain has evolved to provide the most specific platform for activation by agonists, and the cytoplasmic domains may contain common structural features because of their interaction with structurally conserved G proteins, arrestins, and GPCR kinases. The cytoplasmic surfaces allow individual receptors to be differentially and selectively regulated. Even though rhodopsin is a prototypical model system for the other GPCRs, progress on the structure of other receptors, including transmembrane domains, will add a new molecular understanding of receptor function. Thus, the study of rhodopsin and other GPCRs is poised for an exciting expansion in which many concepts will be challenged and new ones will emerge, ultimately leading to a fundamental understanding of the process of cellular signaling.

FUTURE ISSUES TO BE RESOLVED

The changes in structure that transform rhodopsin from its inactive to active conformation capable of interacting with partner proteins should be determined.

High-resolution structures of the complex formed by the photoactivated monomer or dimer of rhodopsin and G protein transducin and the complex formed by the photoactivated phosphorylated monomer or dimer of rhodopsin and arrestin (or its splice form) should be identified.

The role of GPCR dimerization and its functions during signaling and desensitization should be explained.

The mechanism of all-trans-retinal’s release and regeneration as 11-cis-retinal should be identified.

The cell biological cycle of rhodopsin, including synthesis, intracellular transport, phagocytosis, and degradation, should be determined.

SUMMARY POINTS

The structure of rhodopsin provides the fundamental basis for understanding how this G protein works. The importance of rhodopsin arises from its primary role in vision and also from being part of a large family of cell surface receptors termed G protein–coupled receptors or TM7 receptors.

New X-ray and NMR data provide additional detailed information on the conformation of the chromophore, alternative loop conformation, and the first view of the Meta I rhodopsin intermediate, as well as additional molecular particulars of rhodopsin structure and function.

Like most or all other G protein–coupled receptors, rhodopsin displays a propensity to oligomerize. This property appears to be fundamental in the function and interaction of these receptors with their partner proteins.

New details are emerging on how rhodopsin interacts with G protein transducin. However, we are still far from having a comprehensive molecular picture of the coupling of these two proteins.

An extensive list of additional challenges to understanding how rhodopsin works is presented. Our understanding of many basic features of rhodopsin in the context of the rod cell awaits further intellectual and technical developments.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr. Slawomir Filipek (Warsaw, Poland) for help in the preparation of many figures, of which only a few are used in this publication; Dr. Yan Liang for electron microscope images of the retina; Dr. David Lodowski, Dr. Kevin Ridge, and Dr. Jack S. Saari for comments on the manuscript; Rebecca Birdsong for contributions to side bars and to preparation of the manuscript; and the members of my laboratory for valuable comments. K.P. was supported by National Institutes of Health grant EY09339.

Footnotes

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs): cell surface receptors with a seven-transmembrane helical structure

G proteins: trimeric intracellular proteins so named because they bind to guanine nucleotides GDP and GTP

Rhodopsin: the light-sensitive receptor of rod photoreceptor cells and a well-known GPCR

Chromophore: an organic compound that absorbs light. In vision, the chromophore is 11-cis-retinal

Schiff base: a functional group containing a carbon-nitrogen double bond

Photoisomerization: a molecule’s shift from one isomer to another upon excitation by light

Rod cells: the photoreceptor cells of the retina sensitive to low levels of light

Rod outer segment (ROS): the cylindrical portion of the rod cell containing several to 2000 membranous disks

Two-photon fluorescent microscopy: imaging with the near-simultaneous absorption of two photons by a molecule

References

- 1.Filipek S, Teller DC, Palczewski K, Stenkamp R. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:375–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhandawat V, Reisert J, Yau KW. Science. 2005;308:1931–34. doi: 10.1126/science.1109886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Minke B, Cook B. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:429–72. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heck M, Hofmann KP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10000–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leskov IB, Klenchin VA, Handy JW, Whitlock GG, Govardovskii VI, et al. Neuron. 2000;27:525–37. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–50. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefkowitz RJ. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:413–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fredriksson R, Schioth HB. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1414–25. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.009001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda S, Kadowaki S, Haga T, Takaesu H, Mitaku S. FEBS Lett. 2002;520:97–101. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02775-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirzadegan T, Benko G, Filipek S, Palczewski K. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2759–67. doi: 10.1021/bi027224+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahl SG, Sylte I. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;96:151–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto960302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doggrell SA. Drug News Perspect. 2004;17:615–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bjenning C, Al-Shamma H, Thomsen W, Leonard J, Behan D. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;5:1051–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Foord SM, Bonner TI, Neubig RR, Rosser EM, Pin JP, et al. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:279–88. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McBee JK, Palczewski K, Baehr W, Pepperberg DR. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:469–529. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Filipek S, Stenkamp RE, Teller DC, Palczewski K. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003;65:851–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA, Kobilka BK, Strader DJ, Benovic JL, Dohlman HG, et al. Nature. 1986;321:75–79. doi: 10.1038/321075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridge KD, Abdulaev NG, Sousa M, Palczewski K. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:479–87. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okada T, Palczewski K. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2001;11:420–26. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00227-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okada T, Ernst OP, Palczewski K, Hofmann KP. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:318–24. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01799-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teller DC, Okada T, Behnke CA, Palczewski K, Stenkamp RE. Biochemistry. 2001;40:7761–72. doi: 10.1021/bi0155091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hubbell WL, Altenbach C, Hubbell CM, Khorana HG. Adv Protein Chem. 2003;63:243–90. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(03)63010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakmar TP. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;59:1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)61027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sakmar TP. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2002;14:189–95. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00306-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakmar TP, Menon ST, Marin EP, Awad ES. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:443–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.082901.134348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abdulaev NG. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:399–402. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00164-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teller DC, Stenkamp RE, Palczewski K. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:151–59. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01152-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molday RS. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2491–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Polans A, Baehr W, Palczewski K. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19:547–54. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baylor DA, Lamb TD, Yau KW. J Physiol. 1979;288:613–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampath AP, Rieke F. Neuron. 2004;41:431–43. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molday RS, Molday LL. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:2589–601. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carter-Dawson LD, LaVail MM. 1979. J. Comp. Neurol.188:245–62 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Liang Y, Fotiadis D, Maeda T, Maeda A, Modzelewska A, et al. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48189–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408362200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeon CJ, Strettoi E, Masland RH. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8936–46. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-21-08936.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Penn JS, Williams TP. Exp Eye Res. 1986;43:915–28. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(86)90070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lem J, Krasnoperova NV, Calvert PD, Kosaras B, Cameron DA, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Humphries MM, Rancourt D, Farrar GJ, Kenna P, Hazel M, et al. Nat Genet. 1997;15:216–19. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sung CH, Makino C, Baylor D, Nathans J. 1994. J. Neurosci.14:5818–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Tam BM, Moritz OL, Hurd LB, Papermaster DS. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1369–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.7.1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deretic D, Schmerl S, Hargrave PA, Arendt A, McDowell JH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10620–25. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deretic D, Williams AH, Ransom N, Morel V, Hargrave PA, Arendt A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3301–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500095102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moritz OL, Tam BM, Hurd LL, Peranen J, Deretic D, Papermaster DS. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:2341–51. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.8.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frederick JM, Krasnoperova NV, Hoffmann K, Church-Kopish J, Ruther K, et al. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:826–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deretic D, Traverso V, Parkins N, Jackson F, de Turco EBR, Ransom N. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:359–70. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Redmond TM, Yu S, Lee E, Bok D, Hamasaki D, et al. Nat Genet. 1998;20:344–51. doi: 10.1038/3813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batten ML, Imanishi Y, Maeda T, Tu DC, Moise AR, et al. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10422–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312410200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jin S, Cornwall MC, Oprian DD. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:731–35. doi: 10.1038/nn1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jager S, Palczewski K, Hofmann KP. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2901–8. doi: 10.1021/bi9524068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melia TJ, Jr, Cowan CW, Angleson JK, Wensel TG. Biophys J. 1997;73:3182–91. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78344-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woodruff ML, Wang Z, Chung HY, Redmond TM, Fain GL, Lem J. Nat Genet. 2003;35:158–64. doi: 10.1038/ng1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lem J, Fain GL. Trends Mol Med. 2004;10:150–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Okada T, Takeda K, Kouyama T. Photochem Photobiol. 1998;67:495–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Okada T, Le Trong I, Fox BA, Behnke CA, Stenkamp RE, Palczewski K. J Struct Biol. 2000;130:73–80. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oprian DD, Molday RS, Kaufman RJ, Khorana HG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8874–78. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.24.8874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maeda T, Imanishi Y, Palczewski K. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2003;22:417–34. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(03)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crescitelli F. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:1766. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450100068003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marmor MF, Martin LJ. Surv Ophthalmol. 1978;22:279–85. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(78)90074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuksa V, Imanishi Y, Batten M, Palczewski K, Moise AR. Vis Res. 2003;43:2959–81. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(03)00482-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peteanu LA, Schoenlein RW, Wang Q, Mathies RA, Shank CV. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11762–66. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rohrig UF, Guidoni L, Laio A, Frank I, Rothlisberger U. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15328–29. doi: 10.1021/ja048265r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arnis S, Hofmann KP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7849–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsukamoto H, Terakita A, Shichida Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6303–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500378102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koyanagi M, Terakita A, Kubokawa K, Shichida Y. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:525–28. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03616-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Palczewski K, Kumasaka T, Hori T, Behnke CA, Motoshima H, et al. Science. 2000;289:739–45. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Okada T, Sugihara M, Bondar AN, Elstner M, Entel P, Buss V. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:571–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Okada T, Fujiyoshi Y, Silow M, Navarro J, Landau EM, Shichida Y. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5982–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082666399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li J, Edwards PC, Burghammer M, Villa C, Schertler GF. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:1409–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Stojanovic A, Stitham J, Hwa J. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35932–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.del Valle LJ, Ramon E, Canavate X, Dias P, Garriga P. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4719–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210760200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bourne HR, Meng EC. Science. 2000;289:733–34. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Periole X, Ceruso MA, Mehler EL. Biochemistry. 2004;43:6858–64. doi: 10.1021/bi049949e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fritze O, Filipek S, Kuksa V, Palczewski K, Hofmann KP, Ernst OP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2290–95. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0435715100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kim JM, Altenbach C, Kono M, Oprian DD, Hubbell WL, Khorana HG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12508–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404519101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ebrey T, Koutalos Y. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:49–94. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(00)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bartl FJ, Fritze O, Ritter E, Herrmann R, Kuksa V, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:34259–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505260200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yan EC, Kazmi MA, Ganim Z, Hou JM, Pan D, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9262–67. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1531970100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kusnetzow AK, Dukkipati A, Babu KR, Ramos L, Knox BE, Birge RR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:941–46. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Terakita A, Koyanagi M, Tsukamoto H, Yamashita T, Miyata T, Shichida Y. 2004. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.11:284–89 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Krebs A, Edwards PC, Villa C, Li J, Schertler GF. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50217–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307995200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ruprecht JJ, Mielke T, Vogel R, Villa C, Schertler GF. EMBO J. 2004;23:3609–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Vogel R, Ruprecht J, Villa C, Mielke T, Schertler GF, Siebert F. J Mol Biol. 2004;338:597–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Creemers AF, Kiihne S, Bovee-Geurts PH, DeGrip WJ, Lugtenburg J, de Groot HJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9101–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112677599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lugtenburg J. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50(Suppl 3):S17–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spooner PJ, Sharples JM, Goodall SC, Seedorf H, Verhoeven MA, et al. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13371–78. doi: 10.1021/bi0354029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spooner PJ, Sharples JM, Goodall SC, Bovee-Geurts PH, Verhoeven MA, et al. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:719–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patel AB, Crocker E, Eilers M, Hirshfeld A, Sheves M, Smith SO. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10048–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402848101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Borhan B, Souto ML, Imai H, Shichida Y, Nakanishi K. Science. 2000;288:2209–12. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Patel AB, Crocker E, Reeves PJ, Getmanova EV, Eilers M, et al. J Mol Biol. 2005;347:803–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.01.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schadel SA, Heck M, Maretzki D, Filipek S, Teller DC, et al. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24896–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302115200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sommer ME, Smith WC, Farrens DL. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6861–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Medina R, Perdomo D, Bubis J. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39565–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K. Nature. 2003;421:127–28. doi: 10.1038/421127a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K. FEBS Lett. 2004;564:281–88. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00194-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Suda K, Filipek S, Palczewski K, Engel A, Fotiadis D. Mol Membr Biol. 2004;21:435–46. doi: 10.1080/09687860400020291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jastrzebska B, Maeda T, Zhu L, Fotiadis D, Filipek S, et al. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:54663–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408691200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liebman PA, Parker KR, Dratz EA. Annu Rev Physiol. 1987;49:765–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.49.030187.004001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liebman PA, Entine G. Science. 1974;185:457–59. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4149.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Poo M, Cone RA. Nature. 1974;247:438–41. doi: 10.1038/247438a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cone RA. Nat New Biol. 1972;236:39–43. doi: 10.1038/newbio236039a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Saibil H, Chabre M, Worcester D. Nature. 1976;262:266–70. doi: 10.1038/262266a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Angers S, Salahpour A, Bouvier M. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:409–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091701.082314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Terrillon S, Bouvier M. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:30–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Milligan G, Ramsay D, Pascal G, Carrillo JJ. Life Sci. 2003;74:181–88. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Angers S, Salahpour A, Bouvier M. Life Sci. 2001;68:2243–50. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dean MK, Higgs C, Smith RE, Bywater RP, Snell CR, et al. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4595–614. doi: 10.1021/jm010290+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Park PS, Filipek S, Wells JW, Palczewski K. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15643–56. doi: 10.1021/bi047907k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Javitch JA. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1077–82. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.006320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Park PS, Palczewski K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8793–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504016102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Rajan RS, Kopito RR. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:1284–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406448200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Filipek S, Krzysko KA, Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Saperstein DA, et al. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:628–38. doi: 10.1039/b315661c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Liang Y, Fotiadis D, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Palczewski K, Engel A. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21655–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302536200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Natochin M, Gasimov KG, Moussaif M, Artemyev NO. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37574–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wang X, Kim SH, Ablonczy Z, Crouch RK, Knapp DR. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11153–62. doi: 10.1021/bi049642f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Janz JM, Farrens DL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29767–73. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402567200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhang Z, Melia TJ, He F, Yuan C, McGough A, et al. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33937–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403404200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Brabazon DM, Abdulaev NG, Marino JP, Ridge KD. Biochemistry. 2003;42:302–11. doi: 10.1021/bi0268899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rodbell M. Biosci Rep. 1995;15:117–33. doi: 10.1007/BF01207453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schlegel W, Kempner ES, Rodbell M. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:5168–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Carrillo JJ, Pediani J, Milligan G. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42578–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Baneres JL, Parello J. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:815–29. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00439-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kim JM, Hwa J, Garriga P, Reeves PJ, RajBhandary UL, Khorana HG. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2284–92. doi: 10.1021/bi048328i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Kobilka BK, Kobilka TS, Daniel K, Regan JW, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Science. 1988;240:1310–16. doi: 10.1126/science.2836950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Urizar E, Montanelli L, Loy T, Bonomi M, Swillens S, et al. EMBO J. 2005;24:1954–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Janz JM, Farrens DL. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55886–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408766200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Heck M, Schadel SA, Maretzki D, Bartl FJ, Ritter E, et al. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3162–69. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209675200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Maeda A, Maeda T, Imanishi Y, Kuksa V, Alekseev A, et al. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18822–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501757200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Rader AJ, Anderson G, Isin B, Khorana HG, Bahar I, Klein-Seetharaman J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7246–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401429101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhu L, Jang GF, Jastrzebska B, Filipek S, Pearce-Kelling SE, et al. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53828–39. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408472200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Cideciyan AV, Jacobson SG, Aleman TS, Gu D, Pearce-Kelling SE, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:5233–38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408892102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ramon E, del Valle LJ, Garriga P. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6427–32. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Noorwez SM, Kuksa V, Imanishi Y, Zhu L, Filipek S, et al. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:14442–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300087200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Saliba RS, Munro PM, Luthert PJ, Cheetham ME. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2907–18. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.14.2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Li T, Sandberg MA, Pawlyk BS, Rosner B, Hayes KC, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11933–38. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Oesterhelt F, Oesterhelt D, Pfeiffer M, Engel A, Gaub HE, Muller DJ. Science. 2000;288:143–46. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Imanishi Y, Batten ML, Piston DW, Baehr W, Palczewski K. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:373–83. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Imanishi Y, Gerke V, Palczewski K. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:447–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Chan F, Bradley A, Wensel TG, Wilson JH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9109–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403149101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Stone WL, Farnsworth CC, Dratz EA. Exp Eye Res. 1979;28:387–97. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(79)90114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Calvert PD, Govardovskii VI, Krasnoperova N, Anderson RE, Lem J, Makino CL. Nature. 2001;411:90–94. doi: 10.1038/35075083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Aveldano MI. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;324:331–43. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Davidson FF, Loewen PC, Khorana HG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4029–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.9.4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Getmanova E, Patel AB, Klein-Seetharaman J, Loewen MC, Reeves PJ, et al. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1126–33. doi: 10.1021/bi030120u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kisselev OG, Downs MA, McDowell JH, Hargrave PA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51203–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407341200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Argos P, Rao JK, Hargrave PA. Eur J Biochem. 1982;128:565–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb07002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Hargrave PA, McDowell JH, Curtis DR, Wang JK, Juszczak E, et al. Biophys Struct Mech. 1983;9:235–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00535659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Kim JE, Tauber MJ, Mathies RA. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13774–78. doi: 10.1021/bi0116137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Zimmermann K, Ritter E, Bartl FJ, Hofmann KP, Heck M. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48112–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Vogel R, Siebert F, Mathias G, Tavan P, Fan G, Sheves M. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9863–74. doi: 10.1021/bi034684+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Shichida Y, Imai H. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:1299–15. doi: 10.1007/s000180050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Ohguro H, Rudnicka-Nawrot M, Buczylko J, Zhao X, Taylor JA, et al. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5215–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Wang ZY, Wen XH, Ablonczy Z, Crouch RK, Makino CL, Lem J. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24293–300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502588200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Arshavsky VY, Lamb TD, Pugh EN., Jr Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:153–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.082701.102229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rattner A, Sun H, Nathans J. Annu Rev Genet. 1999;33:89–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi L, Javitch JA. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;42:437–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.091101.144224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]