Abstract

Studies on subjective body odour ratings suggest that humans exhibit preferences for human leucocyte antigen (HLA)-dissimilar persons. However, with regard to the extreme polymorphism of the HLA gene loci, the behavioural impact of the proposed HLA-related attracting signals seems to be minimal. Furthermore, the role of HLA-related chemosignals in same- and opposite-sex relations in humans has not been specified so far. Here, we investigate subjective preferences and brain evoked responses to body odours in males and females as a function of HLA similarity between odour donor and smeller. We show that pre-attentive processing of body odours of HLA-similar donors is faster and that late evaluative processing of these chemosignals activates more neuronal resources than the processing of body odours of HLA-dissimilar donors. In same-sex smelling conditions, HLA-associated brain responses show a different local distribution in male (frontal) and female subjects (parietal). The electrophysiological results are supported by significant correlations between the odour ratings and the amplitudes of the brain potentials. We conclude that odours of HLA-similar persons function as important social warning signals in inter- and intrasexual human relations. Such HLA-related chemosignals may contribute to female and male mate choice as well as to male competitive behaviour.

Keywords: human leucocyte antigen, body odour, event-related potential, HLA-related chemosignals

1. Introduction

Several experimental studies have demonstrated that the individual body odour in many vertebrates is associated with their allelic profile of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC; reviewed by Singh 2001). Due to these MHC-related chemosignals individuals prefer to mate with a conspecific that differs at the MHC (reviewed by Penn 2002). However, while most studies indicate female mate choice (Potts et al. 1991), some also point to the possibility of male mate choice (Yamazaki et al. 1976; Olsson et al. 2003). As female mice prefer MHC-similar females as nest mates (Manning et al. 1992), kin recognition also seems to be mediated by the MHC type.

MHC-associated chemosignals have been proposed to affect sexual selection in order to preserve MHC polymorphism. The extreme polymorphism in MHC genes is assumed to have an evolutionary advantage in most vertebrates (e.g. heterozygote and rare allele advantage, inbreeding avoidance; reviewed by Brown & Eklund 1994 and Penn & Potts 1999). However, while sexual selection is traditionally considered to include inter- and intrasexual components (Moshkin et al. 2000; Moore et al. 2001; Olsson et al. 2003), it has not been shown whether the MHC also contributes to male competitive behaviour.

In humans, the MHC is referred to as human leucocyte antigen (HLA). Subjective rating studies, using T-shirts as the odour source, indicate that odours of people with a low (Wedekind & Füri 1997) or intermediate (Jacob et al. 2002) number of HLA allele matches are preferred, compared to odours of people with a high number of HLA matches. In investigating same- and opposite-sex relations between odour donors and perceivers, the strongest correlation between HLA-dissimilarity and odour pleasantness was unexpectedly observed in the intra-sexual male condition (Wedekind & Füri 1997). Generally, the behavioural consequences of these HLA-related odour preferences in humans are considered to be related to mate choice (Ober et al. 1997), and to the degree of acquaintance between unrelated people (Eggert et al. 1999a). Again, the strongest HLA effects on the degree of acquaintance were found in male-to-male relations.

In order to understand how HLA-related chemosignals influence human information processing, the present study employed chemosensory event-related potentials (CSERPs; Kobal & Hummel 1988) as an objective indicator of the neuronal activity associated with the perception of HLA-related chemosignals. CSERPs are the averaged epochs of the electroencephalogram (EEG) that occur time-locked to the chemosensory stimulus. Latency and amplitude of the CSERP components can provide information as to whether differences between HLA-related chemosignals are already reflected in early, exogenous components (N1, ∼400 ms post-stimulus) or only influence late, endogenous components (P3, ∼1000 ms post-stimulus; see Pause & Krauel 2000). Exogenous potentials such as the early negative deflection (N1) reflect mainly pre-attentive processing of external stimulus characteristics (quality, intensity; Pause et al. 1996, 1997). Endogenous potentials such as the late positive deflection (P3) occur in response to rare (unexpected) stimuli and increase in amplitude with the subjective meaning of a stimulus, e.g. when the rare stimulus has to be responded to or is of subjective importance to the perceiver. These components can be elicited in course of the well established oddball paradigm (Donchin & Coles 1988). Within the oddball paradigm, rare stimuli are interspersed among frequent standard stimuli. In the current paradigm, the rare odour stimuli either served as the target stimulus, subjects had to detect and respond to, or served as the distractor stimulus, in order to study evaluative processes independent of task demands.

Summarizing, the aim of the present study was to investigate whether human electrical brain responses to body odour depend on the HLA class-I compatibility between sender and perceiver. In order to investigate HLA effects in same- and opposite-sex relations, CSERPs of male and female subjects in response to odours of male and female donors were analysed. In separating early from late CSERP components, it was addressed whether HLA-associated chemosignals are processed pre-attentively and/or consciously.

2. Material and methods

(a) Subjects

Forty subjects reporting no history of neurological or endocrine diseases, or diseases related to the upper respiratory tract participated in the study. Due to missing EEG data, two subjects were excluded from further analysis (S12 and S33, see table 1). The final subject sample (mean age=26.9, s.d.=4.7, range=20–41, no group differences (ANOVA): F(3,34)=1.27, p>0.20) included three smokers (no group differences (Craddock-Flood): χ32=3.77, p>0.20), and 29 dextrals, six sinistrals and three ambidexters (no group differences (Craddock-Flood): χ62=4.53, p>0.20). Thirty-six subjects described themselves as heterosexual and two (one male) as bisexual. A screening for olfactory sensitivity (mixture of citral, eugenol, linalool, menthol and isoamyl acetate) at the beginning of the experiment revealed no group differences (Craddock-Flood: χ62=2.73, p>0.20). All female subjects were investigated at the beginning of their menstrual cycle (mean cycle day=3.5, s.d.=1.8) and 11 of them used oral contraceptives (no group differences (Craddock-Flood): χ12=0.38, p>0.20). The subjects participated voluntarily in the study, gave written, informed consent and were paid for participation.

Table 1.

Design and specification of HLA class I types.

| sex of subject | sex of donor | subjects (S) | donors (D) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| standard stimulus HLA-dissimilar | deviant stimulus 1 HLA-dissimilar | deviant stimulus 2 HLA-similar | |||||||

| no. | HLA-type | no. | HLA-type | no. | HLA-type | no. | HLA-type | ||

| female | same sex | S1 | A2,3 B7,62 | D1 | A1,24 B8,35 | D2 | A1,24 B8,44 | D3 | A2,3 B7,60 |

| S2 | A2,2 B44,62 | D4 | A3,11 B35,47 | D5 | A3,11 B35,35 | D6 | A2,2 B44,62 | ||

| S3 | A1,25 B8,18 | D7 | A2,11 B35,39 | D8 | A2,11 B18,35 | D9 | A1,25 B18,57 | ||

| S4 | A1,25 B18,57 | D10 | A3,24 B35,51 | D11 | A3,24 B35,61 | D12 | A1,25 B8,18 | ||

| S5 | A2,24 B7,62 | D13 | A1,25 B18,57 | D12 | A1,25 B8,18 | D14 | A2,24 B7,62 | ||

| S6 | A3,24 B35,61 | D15 | A2,29 B44,44 | D16 | A2,29 B44,56 | D10 | A3,24 B35,51 | ||

| S7 | A2,26 B37,44 | D17 | A1,24 B8,58 | D1 | A1,24 B8,35 | D18 | A2,26 B7,44 | ||

| S8 | A1,1 B8,8 | D19 | A2,26 B7,44 | D18 | A2,26 B7,44 | D20 | A1,1 B8,8 | ||

| S9 | A3,11B 35,35 | D21 | A2,2 B44,62 | D6 | A2,2 B44,62 | D4 | A3,11 B35,47 | ||

| S10 | A1,25B 18,57 | D22 | A2,3 B7,7 | D23 | A2,3 B7,62 | D9 | A1,25 B18,57 | ||

| opposite sex | S11 | A1,2 B8,60 | D24 | A3,3 B35,44 | D25 | A3,3 B27,35 | D26 | A1,2 B8,60 | |

| S12 | A2,3 B7,7 | D27 | A1,1 B35,57 | D28 | A1,1 B8,35 | D29 | A2,3 B7,7 | ||

| S13 | A3,3 B18,35 | D26 | A1,2 B8,60 | D30 | A1,2 B37,60 | D25 | A3,3 B27,35 | ||

| S14 | A1,24 B8,35 | D31 | A2,2 B60,60 | D32 | A2,2 B7,60 | D33 | A1,24 B8,51 | ||

| S15 | A2,3 B7,60 | D28 | A1,1 B8,35 | D34 | A1,11 B8,35 | D35 | A2,3 B7,60 | ||

| S16 | A1,1 B8,8 | D36 | A2,30 B27,51 | D37 | A2,2 B27,51 | D28 | A1,1 B8,35 | ||

| S17 | A2,3 B35,60 | D33 | A1,24 B8,51 | D38 | A1,24 B7,8 | D39 | A2,3 B13,35 | ||

| S18 | A1,11 B35,44 | D32 | A2,2 B7,60 | D40 | A2,2 B7,7 | D34 | A1,11 B8,35 | ||

| S19 | A3,3 B7,44 | D41 | A1,24 B8,62 | D33 | A1,24 B8,51 | D24 | A3,3 B35,44 | ||

| S20 | A1,24 B8,44 | D42 | A2,3 B35,51 | D39 | A2,3 B13,35 | D38 | A1,24 B7,8 | ||

| male | same sex | S21 | A24,25 B18,62 | D26 | A1,2 B8,60 | D43 | A1,3 B8,60 | D44 | A24,25 B18,18 |

| S22 | A1,1 B8,35 | D35 | A2,3 B7,60 | D29 | A 2,3 B7,7 | D34 | A1,11 B8,35 | ||

| S23 | A2,3 B27,62 | D38 | A1,24 B7,8 | D33 | A1,24 B8,51 | D45 | A2,3 B62,62 | ||

| S24 | A1,11 B8,35 | D32 | A2,2 B7,60 | D31 | A2,2 B60,60 | D28 | A1,1 B8,35 | ||

| S25 | A2,2 B60,60 | D24 | A3,3 B35,44 | D25 | A3,3 B27,35 | D32 | A2,2 B7,60 | ||

| S26 | A2,2 B27,51 | D41 | A1,24 B8,62 | D38 | A1,24 B7,8 | D36 | A2,30 B27,51 | ||

| S27 | A1,3 B7,8 | D36 | A2,30 B27,51 | D37 | A2,2 B27,51 | D43 | A1,3 B8,60 | ||

| S28 | A2,2 B7,7 | D28 | A1,1 B8,35 | D34 | A1,11 B8,35 | D29 | A2,3 B7,7 | ||

| S29 | A2,3 B13,35 | D46 | A24,25 B18,62 | D44 | A24,25 B18,18 | D42 | A2,3 B35,51 | ||

| S30 | A3,3 B7,7 | D47 | A1,2 B8,51 | D26 | A1,2 B8,60 | D48 | A3,3 B7,7 | ||

| opposite sex | S31 | A 25,33 B7,18 | D10 | A3,24 B35,51 | D11 | A3,24 B35,61 | D49 | A2,25 B7,18 | |

| S32 | A 1,1 B35,57 | D50 | A2,24 B39,44 | D51 | A2,24 B27,44 | D52 | A1,1 B8,57 | ||

| S33 | A3,3 B35,44 | D53 | A2,11 B50,60 | D54 | A2,11 B38,60 | D55 | A3,3 B7,44 | ||

| S34 | A1,2 B8,60 | D56 | A3,3 B18,35 | D57 | A3,30 B18,35 | D58 | A1,2 B8,60 | ||

| S35 | A2,3 B7,7 | D9 | A1,25 B18,57 | D12 | A1,25 B8,18 | D22 | A2,3 B7,7 | ||

| S36 | A1, 24 B8,51 | D59 | A2,25 B18,62 | D49 | A2,25 B7,18 | D1 | A1,24 B8,35 | ||

| S37 | A2,3 B7,60 | D60 | A1,24 B8,27 | D1 | A1,24 B8,35 | D3 | A2,3 B7,60 | ||

| S38 | A2,24 B7,62 | D13 | A1,25 B 18,57 | D9 | A1,25 B18,57 | D61 | A2,24 B7,62 | ||

| S39 | A24,25 B18,18 | D62 | A1,2 B8,57 | D63 | A1,2 B8,57 | D64 | A24,25 B18,51 | ||

| S40 | A1,3 B8,60 | D16 | A2,29 B44,56 | D15 | A2,29 B44,44 | D65 | A1,3 B7,60 | ||

(b) Body odours and odour presentation

Odour samples (axillary hair) from 61 donors were collected (table 1). As some donated for more than one experimental session, the number of odour donors for each experimental group varied between 18 and 24. The final donor sample had a mean age of 27.7 years (s.d.=5.7; no group differences (ANOVA): F(3,82)=1.01, p>0.20) and seven of them described themselves as regular smokers (no group differences (Craddock-Flood): χ32=0.167, p>0.20). The donating subjects declared that they did not suffer from any endocrine disorder and were asked to refrain from using deodorants and to wash their armpits exclusively with water 2 days before the axillary hair was collected. Furthermore, they were requested to refrain from eating onions, garlic or asparagus and had to keep nutrition and hygiene diaries. All subjects cut their axillary hair in the morning, immediately after waking up. The females were additionally asked to cut their hair in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, within a few days after the end of menstruation (mean cycle day=6.1, s.d.=1.8). Axillary hair samples were stored at −20 °C until use (mean storage time=48 days, s.d.=42). All donors were paid for their cooperation.

For the EEG sessions, the axillary hairs were placed in odour chambers (mean=33.3 mg hairs in each chamber, s.d.=9.6) of a constant-flow (2×3-) olfactometer (Burghart Company, Wedel, Germany). Odours were presented birhinally by independent airstreams (100 ml s−1) for 600 ms each with an interstimulus interval of 18–22 s (mean=20 s). During stimulus presentation, subjects performed the velopharyngeal closure technique (Pause et al. 1999a). Thereby, the soft palate closes the connection between the oral and the nasal cavity, and because the subjects are breathing through their mouth, the odour presentations do not interfere with the nasal breathing cycle.

(c) Design

In our study, all subjects and odour donors (donation of samples of axillary hair) were serologically tissue-typed for their A- and B-loci (HLA-class I). Three odour donors were individually assigned to each of 40 (20 males) subjects (table 1). Whereas two of the donors shared none of the detected HLA class I alleles with the perceiving subject (standard stimulus and deviant stimulus 1, condition: HLA-dissimilar), one of them shared at least three alleles (deviant stimulus 2, condition: HLA-similar). As the subjects perceived the foreign body odours always in the context of their own body odour, it might have been more difficult to detect of the deviant stimulus 2 (HLA-similar). In order to obtain a similar context odour for the deviant stimulus 1 (HLA-dissimilar), the standard stimulus was chosen to be similar to the deviant stimulus 1.

A three-stimulus oddball design was used to differentiate HLA effects on automatic (pre-attentive) and on controlled (conscious) stimulus processing. Within the oddball paradigm, the standard odours were presented with an occurrence probability of 60% and the two deviant stimuli with a probability of 20% each. During four blocks of 50 trials, the deviant stimuli were alternatively presented as targets or distractors. The subjects' task was to detect the target odour by lifting their right index finger (response initiation by a 160 Hz tone, 3–4 s after odour onset). However, they were not informed about the occurrence of the distractor odour.

At the beginning of each 50-trial block, standard and target odours were introduced to the subjects. They were asked whether they disliked or liked the odour and whether they could imagine having a partner with such a body odour (seven-point scale for each rating: −3 to +3). Both ratings were highly correlated (r=+0.86, p<0.001). However, further analyses of the subjective data were exclusively based on the ratings for partner preferences, because they were closer to a normal distribution than the ratings for general odour valence (Kurtosis analysis).

(d) EEG recording and analysis

The EEG was recorded unipolarly from seven electrode positions (F3, Fz, F4, Cz, P3, Pz, P4) in reference to linked mastoids (bandpass: 0.016–30 Hz) and grounded at the position Oz. The recording time was 6 s for each trial, including 1 s baseline (sample rate=128 Hz). Eye movements were corrected off-line (Elbert et al. 1985). For peak detection (maximum amplitudes) the bandpass was set to 0.053–4.7 Hz.

Within the averaged potential, four peaks (N1, P2, P3-1, P3-2) were detected in relation to the averaged baseline (Pause et al. 1996). However, only those peaks which represented early exogenous or late endogenous stimulus processing were considered for further analysis. Therefore, CSERPs in response to the detected and rejected standard odours were compared with the CSERPs in response to the detected and rejected target odours (three-way ANOVA: detection (correct rejection, false alarms, hits, misses), anterior/posterior and hemisphere (left, central, right)). As the standard stimuli exclusively belonged to HLA-dissimilar donors, these analyses were carried out for odour stimuli from HLA-dissimilar odour donors only. Exogenous potentials were considered not to vary with the subjective stimulus significance, whereas endogenous potentials should be larger in response to subjectively meaningful (detected) stimuli.

The main statistical analysis was performed by means of a six-way ANOVA, including the factors HLA (similar/dissimilar), odour donor (same sex, opposite sex), subject (female, male), detection (hits, correctly rejected distractors), anterior/posterior and hemisphere. In case of significant interactions including the HLA factor, further analyses were carried out by isolating simple HLA effects within selected interactions, according to Levine (1991). By analysing the nested effects within selected interactions, multiple testing of single comparisons is avoided. As the standard odours did not vary in terms of HLA similarity, the main analysis was carried out for the deviant odours only.

3. Results

(a) Detection performance

Across all conditions, 50.3% of the targets were correctly detected, and 74.6% of the standards and 52.6% of the distractors were correctly rejected. The subjects' detection performance was independent of HLA-related differences.

(b) CSERPs in response to detected and undetected odour stimuli

The amplitude of the N1 was generally larger in response to rare (hits: 2.01 μV, misses: 1.84 μV) than to frequent stimuli (correct rejections: 1.17 μV, false alarms: 1.10 μV; F(3,845)=8.50, p=0.004). However, the N1 was unaffected by the subjective task relevance of the odours. On the contrary, the amplitude of the P3-2 did vary with the subjective stimulus meaning (F(3,845)=5.61, p=0.019): it was larger in response to detected odours (hits: 4.17 μV, false alarms: 4.27 μV) than to undetected odours (correct rejections: 3.55 μV, misses: 3.10 μV). Additionally, the P3-2 showed a parietal maximum (F(1,845)=219.44, p<0.001; anterior: 2.05 μV, posterior: 5.5 μV) and was largest above the midline (F(2,845)=22.50, p<0.001; left: 3.04 μV, central: 4.86 μV, right: 3.42 μV). As the P2 and the P3-1 were neither affected by the level of detection nor by the probability of stimulus occurrence, they were not considered in further analyses.

(c) CSERPs in response to odours of HLA-similar and HLA-dissimilar donors

The CSERP analyses show that across all subjects body odours of HLA-similar donors were processed faster than those of HLA-dissimilar donors (Main effect of HLA-similarity on N1 peak-latency: F(1,34)=7.45, p=0.010, power=0.755; HLA-similar: 384.5 ms, HLA-dissimilar: 407.7 ms). However, the speed of late, evaluative odour processing (P3-2) was not affected by the degree of HLA similarity between subject and odour donor.

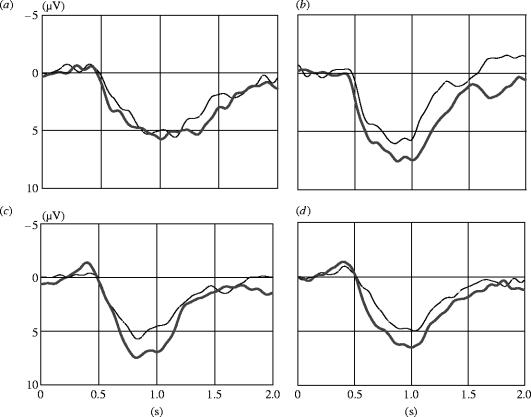

Additionally, HLA-related differences between odour donors and perceivers affected the strength of the neuronal brain response during late, evaluative stimulus processing (see figure 1a–d). Odours of HLA-similar persons evoked larger P3-2 potentials than odours of HLA-dissimilar donors (HLA×anterior/posterior×hemisphere: F(2,68)=7.52, p=0.010, power=0.935). Analyses of the simple main effects revealed that HLA-related differences were most prominent above medial posterior scalp areas (Pz; F(1,37)=7.58, p=0.009, power=0.765).

Figure 1.

Grand averages across all subjects in response to body odours from HLA-similar donors (bold lines) and HLA-dissimilar donors (thin lines). (a) Females smelling females. (b) Females smelling males. (c) Males smelling males. (d) Males smelling females. All recordings from Pz; at time point 0 the odorous flow was activated.

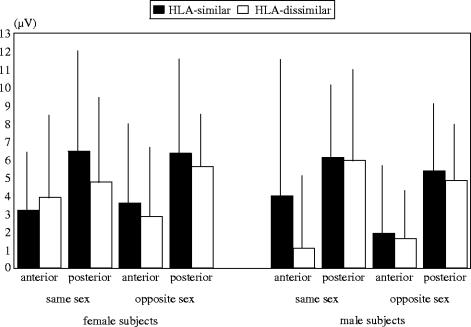

The local distribution of the HLA-effects on the P3-2 potential was modulated by the sex of the odour donors and of the subjects. Generally, in same-sex smelling conditions (men smelling male odour or females smelling female odour), potentials evoked by odours of HLA-similar donors were larger than the cortical evoked responses to odours of HLA-dissimilar donors at medial parietal electrodes (HLA×odour donor×anterior/posterior×hemisphere: F(2,68)=5.03, p=0.032, power=0.800; nested effect for Pz: F(1,37)=8.29, p=0.007, power=0.801). However, analysing female and male subjects separately (HLA×odour donor×subject×anterior/posterior: F(1,34)=8.08, p=0.008, power=0.789) it could be found that males show larger P3-2 amplitudes in response to odours of HLA-similar males above frontal scalp areas (F(1,37)=7.90, p=0.008, power=0.782), whereas females show larger potentials to odours of HLA-similar females above parietal scalp areas (F(1,37)=5.88, p=0.020, power=0.656; see figure 2).

Figure 2.

P3-2 amplitudes (means and standard deviations) in response to HLA-similar and dissimilar odour donors: separation for anterior and posterior electrode positions and for the sex of the subjects and of the odour donors (HLA×odour donor×subject×anterior/posterior; p=0.008).

(d) Subjective ratings

Group mean differences of subjective rating data indicate that subjects tended to reject body odours of donors with a similar HLA-type more than those with a dissimilar HLA-type (table 2). Moreover, correlations (Pearson) between the ratings for the potential partner preference and the P3-2 amplitude (μV; table 2) revealed significant results: high correlations were solely observed when subjects smelled odours from HLA-similar persons of the same sex (p<0.05). In females, the P3-2 amplitude increased, the more negatively the body odours were evaluated. In males, the P3-2 amplitude was larger, the more positively the body odours were judged.

Table 2.

Mean ratings for the potential partner preferences and correlations with the P3-2 amplitude. (Note: Ratings varied between −3 (least preference) and +3 (highest preference). Correlations were performed across all six electrodes (F3, Fz, F4, P3, Pz, P4). Level of significance: *p<0.05.)

| design | rating (mean) | correlation (Pearson) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| subject | donor | HLA | ||

| females | same sex | similar | −0.05 | −0.67* |

| dissimilar | +0.25 | −0.35 | ||

| opposite sex | similar | +0.22 | −0.30 | |

| dissimilar | +0.33 | −0.20 | ||

| males | same sex | similar | −0.70 | +0.75* |

| dissimilar | −0.35 | +0.02 | ||

| opposite sex | similar | −0.11 | −0.01 | |

| dissimilar | −0.11 | +0.24 | ||

4. Discussion

First, the CSERP results as well as the correlation analyses of the subjective ratings reveal that odours of HLA-similar persons convey significant information, whereas odours of HLA-dissimilar persons are perceived as less relevant. Second, both analyses point to the conclusion that males and females process HLA-related chemosignals of the same sex differently.

The CSERP results are related to two components, which reflect exogenous (N1) and endogenous (P3-2) stimulus processing (Donchin & Coles 1988). The N1 component did not vary with the subjective task relevance but was larger in response to the rare than to the frequent stimuli. This result is in accordance with the observation that the chemosensory N1 amplitude is prone to show strong (stimulus-specific) effects of habituation (see Pause 2002). On the contrary, the P3-2 component was larger in response to detected than to undetected odours and, additionally, showed a parietal maximum. This result is in line with a number of studies which demonstrate that the chemosensory P3-2 component represents the features of the traditional P3 component (reviewed by Pause & Krauel 2000). As the chemosensory P2 might be related to exogenous stimulus processing and the P3-1 to novelty detection (Pause et al. 1996), their functional significance could not be fully explained with the present data set and they were not considered for the HLA analyses.

In general, and independent of the sex of the odour donor and smeller, CSERPs were larger (P3-2) and appeared with a shorter latency (N1) when the subjects processed body odours from HLA similar donors. We suggest that the HLA effect on the N1 latency is related to the precise neuronal timing within the primary (Spors & Grinvald 2002) and secondary (Lorig 1999) olfactory cortex, which is important for pre-attentive odour quality discrimination. Since the P3-2 is related to cognitive-emotional stimulus evaluation, our results indicate that more attentional resources are activated in response to body odours of HLA-similar donors than to odours from HLA-dissimilar sources.

However, one could argue that the P3-2 in response to HLA-similar donors was larger, because the deviant stimulus 2 (HLA similar) was more different than the deviant stimulus 1 (HLA-dissimilar) from the standard stimulus (HLA-dissimilar, see table 1). However, this interpretation would indicate that HLA-related body odour differences between two people could be detected in general, without relating them to one's own HLA-type. As so far, all evidence in humans points solely to the ability of humans to detect HLA-related body odours in relation to their own HLA-type (Ober et al. 1997; Wedekind & Füri 1997; Jacob et al. 2002) it is argued strongly that the HLA-related differences in brain activity, reported here, are due to the immunogenetic relatedness between the odour donor and the perceiver. Moreover, the N1 effect, which is independent of the oddball design, also refers to the fact that HLA-similarity is processed and is thus in line with the interpretation of the P3-2 effect stated herein.

The fact that information about genetic similarity has a processing advantage in speed as well as in recruitment of neuronal resources is in line with findings on chemosensory and visual self-perception. As the processing of one's own body odour is faster than the processing of non-self chemical signals (Pause et al. 1999b) and as the perception of one's own face activates a distinct and unique neuronal network, including limbic and prefrontal brain areas (Kircher et al. 2001), the existence of a self-detecting neuronal assembly within the human brain seems to be likely. It is proposed that the detection of genetic similarity might be associated with this self-detection system, which, however, might become functional during a sensitive period in ontogenesis (see Yamazaki et al. 1988).

It is further concluded that the behavioural impact of chemosensory signals related to HLA-similarity is stronger than of signals related to HLA-dissimilarity. As the HLA loci are the most polymorphic loci in the human genome (Parham & Ohta 1996), the probability of meeting unrelated individuals with a dissimilar HLA-type is extremely high. Therefore, the development of a preference for potential partners with a dissimilar HLA type might be related to other factors than to chemosensory cues, whereas the rejection of potential partners with a similar or identical HLA type might be most effectively determined by the rarely occurring chemosignals of self. Furthermore, it has been proposed that MHC-regulated inbreeding avoidance might lead to higher fitness benefits than MHC-heterozygosity (Penn 2002). Accordingly, inbreeding avoidance could be successfully achieved if MHC similarity is transmitted as an avoidance behaviour activating signal.

In same sex conditions, the specific brain areas involved in the processing of HLA-related body odours are different in male and female perceivers. In males, large HLA-related potential differences occur above anterior scalp areas and in females above parietal scalp areas. The prefrontal cortex is assumed to play a key-role in the integration of valenced information (Davidson 2002; Anderson et al. 2003), while activity in the parietal cortex seems to be related to emotion-related arousal (Nitschke et al. 2000). It is, therefore, postulated that males process chemosensory signals from HLA-similar males primarily as hedonic information, while females process according signals primarily as arousing information. In line with these considerations, the most negative ratings were given by males responding to same sex odours, whereas in females, the hedonic ratings were less pronounced (table 2; group mean differences might not have reached the significance level, because the number of subjects in our electrophysiological study was much smaller than in studies designed to investigate subjective ratings). Thereby, the positive sign of the correlation in males indicates that emotionally positive odours of HLA-similar males were perceived as unexpected (average ratings are negative) and correspondingly elicited larger potentials. In contrast, females might have responded with larger potentials to odours of other HLA-similar females with an unexpected negative valence (inverse correlation; average ratings are indifferent).

As the CSERPs of females and males, responding to HLA-related body odour signals of opposite sex donors, showed similar features, it remains possible that not only females but also males are involved in human mate selection (Yamazaki et al. 1976; Potts et al. 1991; Olsson et al. 2003). The effect that females also responded to HLA-similarity in same sex conditions, might be equivalent to the effects of kin recognition in female mice, demonstrating that females nest communally and appear to nest with MHC-similar females when siblings are unavailable (Manning et al. 1992). However, the HLA-effect on the chemosensory male–male communication raises the intriguing possibility that competitive behaviour in males may be modulated by HLA-associated chemosignals. So far, it is known that competition in male behaviour and sperm production can be initiated through chemosensory signals of conspecifics (Rich & Hurst 1998; DelBarco-Trillo & Ferkin 2004), and that male competitive behaviour can facilitate female mate choice (Lenington et al. 1992; Candolin 1999). Furthermore, the reduced fitness in inbred mice is related to the reduced survivorship of males in competitive conditions (Meagher et al. 2000). Thus, male competitive behaviour could have evolved secondary to female mate choice (Moore et al. 2001) on the basis of the same MHC-related regulatory mechanisms.

The limitations of our study are related to the unknown relative contribution of the HLA-A and -B loci to the described effects. While so far no study in humans allows us to decide which of the different HLA genes contributes most to the individual body odour, in rats it has been shown that class I as well as class II regions of the MHC are responsible for the individuality of body odours (Brown et al. 1989). However, due to the fact that class I genes are expressed on the surface of all nucleated somatic cells, and that class II genes have a much more restricted expression pattern, most animal research on MHC-related body odours has focused on MHC-class I genes (see Penn 2002). In humans, the HLA-C region is the phylogenetically youngest among the classical class I genes (Kelley et al. 2005), and might, therefore, contribute less to chemosensory communication than the A- and B-region. We and others (Wedekind & Füri 1997) have, therefore, focused the research on HLA-related chemoperception on the A- and B-region.

While HLA-related body odours can be differentiated by rodents (Ferstl et al. 1990) and via analytic technologies (Eggert et al. 1999b; Montag et al. 2001), so far, the signalling properties of these chemosignals have exclusively been reported in human rating studies (Wedekind & Füri 1997; Jacob et al. 2002). In contrast to the latter, our CSERP results show that body odours from HLA-similar sources have a processing advantage and thus may convey more significant information than those from HLA-dissimilar donors. Therefore, in humans, HLA-related signals seem to be associated to a negative selection bias in mating behaviour. Moreover, HLA-associated odour signals from same-sex persons are processed differently in males and females, pointing to different behavioural functions in male-to-male (competition) and female-to-female (communal behaviour) relations.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Schaal, A. N. Gilbert and T. Elbert for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript and F. Eggert for fruitful discussions throughout the experiment. Special thanks to B. Gottsmann, A. Krischer and K. Rogalski for their technical help during data acquisition. The study was supported by a grant from the Volkswagen foundation.

References

- Anderson A.K, Christoff K, Stappen I, Panitz D, Ghahremani D.G, Glover G, Gabrieli J.D.E, Sobel N. Dissociated neural representations of intensity and valence in human olfaction. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:196–202. doi: 10.1038/nn1001. doi:10.1038/nn1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J.L, Eklund A. Kin recognition and the major histocompatibility complex: an integrative review. Am. Nat. 1994;143:435–461. doi:10.1086/285612 [Google Scholar]

- Brown R.E, Roser B, Singh P.B. Class I and class II regions of the major histocompatibility complex both contribute to individual odors in congenic inbred strains of rats. Behav. Genet. 1989;19:659–674. doi: 10.1007/BF01066029. doi:10.1007/BF01066029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candolin U. Male–male competition facilitates female choice in sticklebacks. Proc. R. Soc. B. 1999;266:785–789. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0706 [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R.J. Anxiety and affective style: role of prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Biol. Psychiatry. 2002;51:68–80. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01328-2. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01328-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelBarco J, Ferkin M.H. Male mammals respond to a risk of sperm competition conveyed by odours of conspecific males. Nature. 2004;431:446–449. doi: 10.1038/nature02845. doi:10.1038/nature02845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donchin E, Coles M.G.H. Is the P300 component a manifestation of context updating? Behav. Brain Sci. 1988;11:357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert F, Ferstl R, Müller-Ruchholtz W. MHC and olfactory communication in humans. In: Johnston R.E, Müller-Schwarze D, Sorensen P.W, editors. Advances in chemical signals in vertebrates. Kluwer Academic Press; New York: 1999a. pp. 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Eggert F, Luszyk D, Haberkorn K, Wobst B, Vostrowsky O, Westphal E, Bestmann H.J, Müller-Ruchholtz W, Ferstl R. The major histocompatibility complex and the chemosensory signaling of individuality in humans. Genetica. 1999b;104:265–273. doi: 10.1023/a:1026431303879. doi:10.1023/A:1026431303879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbert T, Lutzenberger W, Rockstroh B, Birbaumer N. Removal of ocular artifacts from the EEG—a biophysical approach. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1985;60:455–463. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(85)91020-x. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(85)91020-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferstl R, Pause B, Schüler M, Luszyk D, Eggert F, Westphal E, Müller-Ruchholtz W. Immune system signaling to the brain: MHC-specific odors in humans. In: Stefanis C.N, Soldatos C.R, Rabavilas A.D, editors. Psychiatry: a world perspective. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1990. pp. 751–755. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob S, McClintock M.K, Zelano B, Ober C. Paternally inherited HLA alleles are associated with women's choice of male odor. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:175–179. doi: 10.1038/ng830. doi:10.1038/ng830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley J, Walter L, Trowsdale J. Comparative genomics of major histocompatibility complexes. Immunogenetics. 2005;56:683–695. doi: 10.1007/s00251-004-0717-7. doi:10.1007/s00251-004-0717-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircher T.T.J, et al. Recognizing one's own face. Cognition. 2001;78:B1–B15. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(00)00104-9. doi:10.1016/S0010-0277(00)00104-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobal G, Hummel C. Cerebral chemosensory evoked potentials elicited by chemical stimulation of the human olfactory and respiratory nasal mucosa. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1988;71:241–250. doi: 10.1016/0168-5597(88)90023-8. doi:10.1016/0168-5597(88)90023-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenington S, Coopersmith C, Williams J. Genetic basis of mating preferences in wild house mice. Am. Zool. 1992;32:40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Levine G. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale: 1991. A guide to SPSS for analysis of variance. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig T.S. On the similarity of odor and language perception. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1999;23:391–398. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(98)00041-4. doi:10.1016/S0149-7634(98)00041-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning C.J, Wakeland E.K, Potts W.K. Communal nesting patterns in mice implicate MHC genes in kin recognition. Nature. 1992;360:581–583. doi: 10.1038/360581a0. doi:10.1038/360581a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montag S, Frank M, Ulmer H, Wernet D, Göpel W, Rammensee H.-G. “Electronic nose” detects major histocompatibility complex-dependent prerenal and postrenal odor components. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:9249–9254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161266398. doi:10.1073/pnas.161266398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meagher S, Penn D.J, Potts W.K. Male–male competition magnifies inbreeding depression in wild house mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:3324–3329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060284797. doi:10.1073/pnas.060284797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A.J, Gowaty P.A, Wallin W.G, Moore P.J. Sexual conflict and the evolution of female mate choice and male social dominance. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2001;268:517–523. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1399. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moshkin M.P, Gerlinskaya L.A, Evsikov V.I. The role of the immune system in behavioral strategies of reproduction. J. Reprod. Dev. 2000;46:341–365. doi:10.1262/jrd.46.341 [Google Scholar]

- Nitschke J.B, Heller W, Miller G.A. Anxiety, stress, and cortical brain function. In: Borod J.C, editor. The neuropsychology of emotion. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2000. pp. 298–319. [Google Scholar]

- Ober C, Weitkamp L.P, Cox N, Dytch H, Kostyu D, Elias S. HLA and mate choice in humans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:497–504. doi: 10.1086/515511. doi:10.1017/S0003480097006532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson M, Madsen T, Nordby J, Wapstra E, Ujvari B, Wittsel H. Major histocompatibility complex and mate choice in sand lizards. Proc. R. Soc. B. 2003;270(Suppl.):S245–S256. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2003.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parham P, Ohta T. Population biology of antigen presentation by MHC class I molecules. Science. 1996;272:67–74. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause B.M. Human brain activity during the first second after odor presentation. In: Rouby C, Schaal B, Dubois D, Gervais R, Holley A, editors. Olfaction, taste, and cognition. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. pp. 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Pause B.M, Krauel K. Chemosensory event-related potentials (CSERP) as a key to the psychology of odors. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 2000;36:105–122. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00105-1. doi:10.1016/S0167-8760(99)00105-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause B.M, Sojka B, Krauel K, Ferstl R. The nature of the late positive complex within the olfactory event-related potential (OERP) Psychophysiology. 1996;33:376–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1996.tb01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause B.M, Sojka B, Ferstl R. Central processing of odor concentration is a temporal phenomenon as revealed by chemosensory event-related potentials (CSERP) Chem. Senses. 1997;22:9–26. doi: 10.1093/chemse/22.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause B.M, Krauel K, Sojka B, Ferstl R. Is odor processing related to oral breathing? Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1999a;32:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8760(99)00020-3. doi:10.1016/S0167-8760(99)00020-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pause B.M, Krauel K, Sojka B, Ferstl R. Body odor evoked potentials: a new method to study the chemosensory perception of self and non-self in humans. Genetica. 1999b;104:285–294. doi: 10.1023/a:1026462701154. doi:10.1023/A:1026462701154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn D.J. The scent of genetic compatibility: sexual selection and the major histocompatibility complex. Ethology. 2002;108:1–21. doi:10.1046/j.1439-0310.2002.00768.x [Google Scholar]

- Penn D.J, Potts W.K. The evolution of mating preferences and major histocompatibility genes. Am. Nat. 1999;153:145–164. doi: 10.1086/303166. doi:10.1086/303166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts W.K, Manning C.J, Wakeland E.K. Mating patterns in seminatural populations of mice influenced by MHC genotype. Nature. 1991;352:619–621. doi: 10.1038/352619a0. doi:10.1038/352619a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich T.J, Hurst J.L. Scent marks as reliable signals of the competitive ability of mates. Anim. Behav. 1988;56:727–735. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1998.0803. doi:10.1006/anbe.1998.0803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P.B. Chemosensation and genetic individuality. Reproduction. 2001;121:529–539. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1210529. doi:10.1530/rep.0.1210529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spors H, Grinvald A. Spatio-temporal dynamics of odor representations in the mammalian olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2002;34:301–315. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00644-x. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00644-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedekind C, Füri S. Body odour preferences in men and women: do they aim for specific MHC combinations or simply heterozygosity? Proc. R. Soc. B. 1997;264:1471–1479. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1997.0204. doi:10.1098/rspb.1997.0204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Boyse E.A, Mike V, Thaler H.T, Mathieson B.J, Abbott J, Boyse J, Zayas Z.A, Thomas L. Control of mating preferences in mice by genes in the major histocompatibility complex. J. Exp. Med. 1976;144:1324–1335. doi: 10.1084/jem.144.5.1324. doi:10.1084/jem.144.5.1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamazaki K, Beauchamp G.K, Kupniewski J, Bard J, Thomas L, Boyse E.A. Familial imprinting determines H-2 selective mating preferences. Science. 1988;240:1331–1332. doi: 10.1126/science.3375818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]