Abstract

The ribonucleoprotein enzyme telomerase maintains chromosome ends in most eukaryotes and is critical for a cell’s genetic stability and its proliferative viability. All telomerases contain a catalytic protein component homologous to viral reverse transcriptases (TERT) and an RNA (TR) that provides the template sequence as well as a scaffold for ribonucleoprotein assembly. Vertebrate telomerase RNAs have three essential domains: the template, activation and stability domains. Here we report the NMR structure of an essential RNA element derived from the human telomerase RNA activation domain. The sequence forms a stem–loop structure stabilized by a GU wobble pair formed by two of the five unpaired residues capping a short double helical region. The remaining three loop residues are in a well-defined conformation and form phosphate-base stacking interactions reminiscent of other RNA loop structures. Mutations of these unpaired nucleotides abolish enzymatic activity. The structure rationalizes a number of biochemical observations, and allows us to propose how the loop may function in the telomerase catalytic cycle. The pre-formed structure of the loop exposes the bases of these three essential nucleotides and positions them to interact with other RNA sequences within TR, with the reverse transcriptase or with the newly synthesized telomeric DNA strand. The functional role of this stem–loop appears to be conserved in even distantly related organisms such as yeast and ciliates.

INTRODUCTION

Organisms with linear chromosomes must protect the ends of their chromosomes (telomeres) from fusion, recombination, spurious DNA repair and the progressive degradation associated with incomplete copying of terminal DNA sequences (1). This task is accomplished in most eukaryotes by the hundreds or sometimes thousands of G-rich repeats that are appended to the ends of chromosomal DNA. These telomeric repeats act as a buffer against DNA degradation and can nucleate specialized chromatin structures that prevent recombination and unnecessary DNA repair (2). These repeats are added by the ribonucleoprotein enzyme telomerase, which is an RNA-dependent DNA polymerase (3).

The RNA (TR) and an enzymatic protein component (TERT) are sufficient to reconstitute telomerase activity in vitro. However, additional protein components are required for regulation of the telomerase holoenzyme activity, for telomerase RNA processing and for ribonucleoprotein assembly (4), and the active form of telomerase likely contains two copies of TR and TERT (5). TERT has an essential reverse transcriptase domain in addition to RNA binding domains, while vertebrate TR has three conserved structural domains (Fig. 1) (6,7), which are involved in telomerase function, at a minimum by providing binding sites for TERT or other telomerase proteins. The template domain contains the RNA sequence used by TERT to reverse transcribe telomeric DNA and is conserved from ciliates to humans. The activation domain interacts with TERT independently of the template (8,9). This interaction dramatically stimulates the enzymatic activity of TERT: mutations within this domain reduce or abolish telomerase activity both in vitro and in vivo. The secondary structure of this domain is highly conserved in vertebrates, but not in lower eukaryotes such as yeast or ciliates (10). However, domains present in the yeast and ciliate TR that are implicated in TERT protein binding and in promoting enzymatic activity may play roles analogous to those of the activation domain found in vertebrates TRs (11,12). A third domain in TR, exclusive to vertebrates, controls telomerase RNA stability and RNP assembly but it is dispensable for telomerase assembly in vitro (8). This domain is remarkably similar in sequence, structure and function to the snoRNA box H/ACA class of nucleolar RNAs (4). It is crucial for the accumulation of a stable and accurately processed ribonucleoprotein (4).

Figure 1.

(a) Secondary structure of human telomerase RNA with the template (blue), activation (red) and stability (green) domains. The minimal activation domain sequence is shown. (b) Proposed secondary structure and sequence of the P6.1 RNA construct studied here. Residues are numbered from 301 to 315 throughout the text and figures to match the numbering in hTR.

The activation domain plays an essential role in telomere maintenance. Deletions or nucleotide changes within not just the template but also the activation domain compromise or abrogate activity (7,13). Furthermore, recent experiments in mouse and human have shown that telomerase activity can be reconstituted with full length TERT and two RNAs representing the separate template and activation domains (7,9); these two domains bind TERT independently (8,13). The complete activation domain contains conserved RNA sequence elements that form secondary structure motifs required for enzymatic activity. The first essential RNA structure within the TR activation domain is a stem–loop interrupted by several unpaired nucleotides and by an internal loop. The second is the smaller P6.1 stem–loop structure identified from mutational analysis, although the extreme sequence conservation prevented its identification as a hairpin from phylogenetic analysis (7) and chemical/enzymatic mapping analysis could not confirm its presence (6). Deletion of the stem–loop abolishes telomerase activity (13), while disruption of the putative base pairs within the double helical stretch eliminates binding of TERT protein. Lengthening of the conserved P6.1 helix abrogates enzymatic activity without affecting TERT protein binding (7).

We have begun the systematic structural dissection of the telomerase activation domain based on the divide-and-conquer approach. As a first step in this investigation, we report here the high resolution NMR structure of the essential P6.1 element from human telomerase RNA activation domain. Adding to two very recent studies of other regions of telomerase (14,15), our results contribute a new high-resolution structure of a component of the human telomerase. They also rationalize a number of biochemical observations and allow us to propose how the loop may function in the telomerase catalytic cycle in human and possibly in all telomerases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

RNA synthesis

The P6.1 RNA hairpin (Fig. 1) was synthesized by in vitro transcription with commercially available unlabeled and 13C/15N labeled nucleotides (purchased from CIL). The 13C/15N labeled nucleotides were purchased in the monophosphate form and phosphorylated in vitro (16). All RNA samples were purified according to published methods (16). Briefly, that entailed in vitro transcription from a DNA template, polyacrylamide gel purification, electroelution, ethanol precipitation, and extensive dialysis to bring the final buffer to 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.5. The RNA was annealed by heating the RNA past its melting temperature then cooling it quickly. For experiments in water, the RNA was dried and re-dissolved with 8% D2O/92% H2O. Experiments involving non-exchangeable resonances used RNA samples dissolved in 100% D2O. P6.1 NMR samples were limited to concentrations of 0.8 mM to avoid any significant duplex formation. When samples were prepared at higher concentrations, additional slowly exchanging NH resonances were observed, indicating the likely formation of a duplex structure in equilibrium with the stem–loop. The new peaks had higher intensity at increasing salt concentration and, conversely, became smaller as the RNA concentration was reduced. At the conditions of the structure determination (low salt buffer and limited RNA concentration), the predominant molecular species was a unimolecular hairpin.

NMR spectroscopy

Initial assignments of the P6.1 structure were based on standard NOESY walk analysis (17). It was straightforward to identify NH resonances from the predicted Watson–Crick base pairs and those corresponding to a GU base pair between the first and last loop residues by analyzing NOESY spectra recorded in water. The well-established patterns of NOE and chemical shifts predicted for Watson–Crick pairs and the very strong NOEs between NH and NH2 resonances within the GU pair, in addition to other NOEs involving the exchangeable resonances, unambiguously provided assignments for all slowly exchanging NH resonances. Loop nucleotides were assigned by two-dimensional (2D)-NOESY and three-dimensional (3D) triple resonance HCP spectra (18,19). An HCCH-COSY experiment (20) was used to complete the ribose assignments, allowing the assignment of nearly every exchangeable and non-exchangeable proton resonance. 3D 13C-NOESY-HSQC spectra were used to obtain NOE distance constraints for the ribose region, to confirm loop assignments and to obtain additional restraints.

Structure determination

Structures were calculated in CNS using torsion angle dynamics and simulated annealing (21). Distance restraints were obtained from 2D NOESY spectra recorded at 800 MHz and short mixing time (80 ms). Additional restraints were obtained from the 3D 13C-NOESY-HSQC recorded at 120 ms mixing time. Distances corresponding to strong, medium or weak NOEs were given bounds of 2.6 ± 1, 3.6 ± 1, 4.0 ± 1.2 Å, respectively. Restraints involving the exchangeable proton resonances were obtained from the 2D water NOESY based on the Watergate water suppression scheme (22). Distance constraints involving exchangeable resonances were only given generous boundaries (4.0 ± 1.5 Å) and were calibrated from the comparison with established distances corresponding to Watson–Crick paired resonances. Weak base pair planarity and standard hydrogen-bonding restraints were used for unambiguously established base pairs. Nucleotides which lacked strong H1′ to aromatic NOEs at 80 ms mixing times were given torsion angle restraints of –158° ± 40 for the glycosidic angle to prevent the syn conformation. The sugar conformation was constrained to 3′-endo for ribose sugars lacking visible H1′ to H2′ cross-peaks in a DQF-COSY spectrum. Assignments of sugar residues to the C2′-endo conformation were based on the observation of strong H1′–H2′ cross-peaks in 2QF-COSY peaks as well as the observation of strong H1′–H2′ and very weak (or non-existent) H3′–H4′ cross-peaks in 2D and 3D TOCSY spectra. Three loop residues had both strong TOCSY and DQF-COSY H1′ to H2′ cross-peaks and were assigned the 2′-endo sugar conformation. The remaining backbone torsion angles were restrained using established methods (17). Briefly, α and ζ were set to exclude the trans conformation for residues with canonical 31P chemical shift values. β was restrained to trans and γ to gauche+ for residues with measurable 4JH4′/iP correlations in the 1H/31P HETCOR spectra. β was also restrained to trans when a strong 3JC4′/iP was present in HCP triple resonance spectra. ε was restrained to trans when an H2′ to P(i + 1) peak was observed in either HCP or HETCOR spectra. For U306, U307 and G310, ε was restrained to gauche– based upon the strong C2′ to P(i + 1) correlation observed in the HCP spectra.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Structure determination

The 3D structure of the essential P6.1 stem–loop from the activation domain of human telomerase was determined by heteronuclear multidimensional NMR (Fig. 1b). NMR measurements were collected following published procedures (17) and distance constraints generated from the NOE data as described in the Methods. Dihedral angle restraints based upon qualitative estimation of coupling constants in ‘through bond’ experiments were used as well. The unambiguous pattern of chemical shifts and NOE interactions involving exchangeable protons justified the use of hydrogen bonding and planarity restraints for based paired residues. A total of 239 experimentally derived distance restraints and 120 dihedral angle restraints were used for structure determination, corresponding to greater than 25 significant (i.e. not conformationally constrained) constraints per residue (Table 1).

Table 1. Restraints/structure statistics.

| Total number of structures calculated | 100 |

|---|---|

| Number of converged structures based upon energy | 70 |

| Structures with no NOE/dihedral violation >0.5 Å/5° | 36 |

| Total number of restraints | 395 |

| NOE (17.9 NOE restraints per residue) | 239 |

| Dihedrals | 120 |

| Hydrogen bonding | 30 |

| Planarity | 6 |

| Average deviation from restraint/ideal geometry (36 structures) | |

| Distance restraints (NOE and H-bond) (Å) | 0.041 |

| Dihedral restraints (°) | 0.701 |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.002 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.663 |

| Impropers (°) | 0.506 |

| RMSD (Å all heavy atoms to the mean structure—36 structures) | |

| All residues | 1.055 |

| Residues 301–306 and 310–315 (Stem and GU pair) | 0.687 |

| Residues 306–310 (loop) | 0.889 |

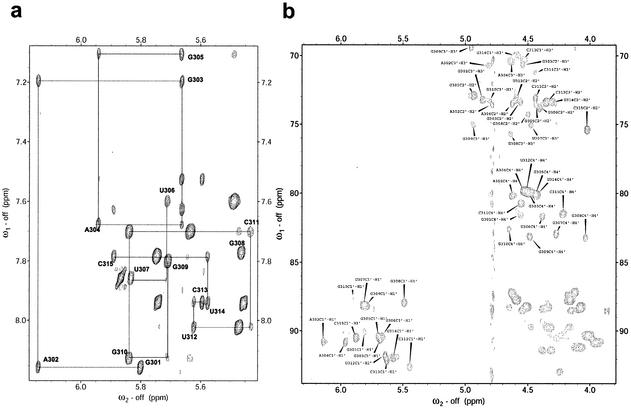

Analysis of the NMR spectra confirmed the predicted secondary structure of the hTR P6.1 hairpin (Fig. 1). In addition to the pattern of NOE and chemical shifts that led to the identification of the predicted Watson–Crick base pairs, the NOESY walk for the anomeric to aromatic proton region (Fig. 2a) supported the secondary structure suggested by the biochemical analysis. The pattern and intensity of NOE interactions involving the well-protected imino resonances of U306 and G310 unambiguously demonstrate that a GU wobble pair forms. Essentially complete assignments of the 1H and 13C nuclei were obtained with heteronuclear labeling (Fig. 2b). Isotope labeling also allowed the stem region to be very well defined by the NMR data. Superposition of stem residues from all 36 structures (out of 100 calculated) lacking any large violations of distance and dihedral constraints, reveals an RMSD <0.7 Å (Fig. 3a). The loop is only slightly less well defined with an RMSD under 0.9 Å. A table summarizing the internucleotide NOEs observed at 80 ms mixing times for loop residues is shown (Table 2). It is of note that only one weak NOE was observed between the G308 and G309 nucleotides (G308-H3′ to G309-H8), highlighting the discontinuity and lack of contacts between these residues. The very weak but unambiguous i to i + 2 NOEs between the H1′ of U306 and the H5′/5″ of G308 were both unexpected and notable.

Figure 2.

(a) 800 MHz NOESY spectrum shows high dispersion indicative of a well-defined structure. (b) 500 MHz 13C ct-HSQC spectrum; 1H-13C correlations are labeled for 1′ to 4′ spin systems.

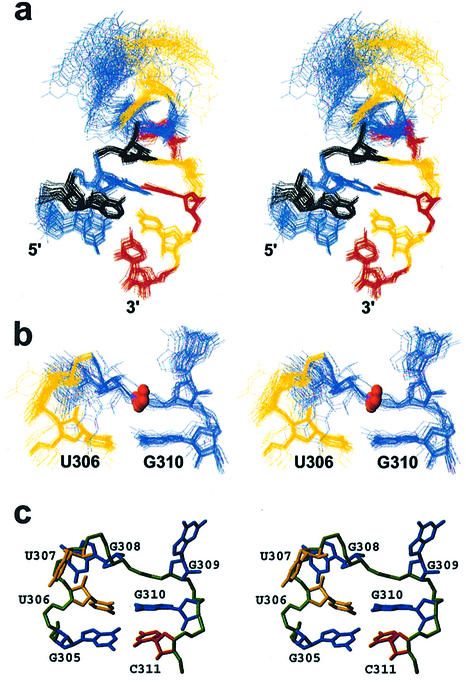

Figure 3.

(a) Superposition of 36 converged structures based on the stem residues. (b) Superposition of residues U306 to G310; the 5′ phosphorus of G309 is indicated by a sphere. (c) A representative structure of the 5 nt P6.1 loop and closing CG pair is shown to highlight the exposure of the three central loop bases U307 to G309.

Table 2. Internucleotide loop NOEs.

| Non-exchangeable NOEs | |||||

| 1 | G305 | H3′ | U306 | H5 | Weak |

| 2 | G305 | H8 | U306 | H5 | Weak |

| 3 | U306 | H2′ | U307 | H6 | Weaka |

| 4 | U306 | H2′ | U307 | H5′/H5″ | Med/weak |

| 5 | U306 | H3′ | U307 | H6 | Weak |

| 6 | U306 | H4′ | U307 | H6 | Weak |

| 7 | U306 | H1′ | G308 | H5′/H5″ | Weakb |

| 8 | U307 | H1′ | G308 | H5′/H5″ | Weak |

| 9 | U307 | H3′ | G308 | H8 | Strong |

| 10 | U307 | H4′ | G308 | H5′/H5″ | Weak |

| 11 | U307 | H4′ | G308 | H8 | Weak |

| 12 | U307 | H5′/5″ | G308 | H1′ | Weak |

| 13 | U307 | H6 | G308 | H5′/H5″ | Weak |

| 14 | G308 | H3′ | G309 | H8 | Weaka |

| 15 | G308 | H8 | G308 | H1′ | Medc |

| 16 | G309 | H2′ | G310 | H1′ | Weak |

| 17 | G309 | H3′ | G310 | H1′ | Strongd |

| 18 | G309 | H3′ | G310 | H8 | Strong |

| 19 | G309 | H4′ | G310 | H8 | Weak |

| 20 | G309 | H5′/5″ | G310 | H8 | Weak |

| 21 | G309 | H8 | G309 | H1′ | Med |

| 22 | G310 | H1′ | G311 | H1′ | Weak |

| 23 | G310 | H1′ | G311 | H5′/H5″ | Weak |

| 24 | G310 | H1′ | G311 | H6 | Medc |

| 25 | G310 | H2′ | G311 | H6 | Strong |

| 26 | G310 | H3′ | G311 | H6 | Med |

| 27 | G310 | H8 | G311 | H5 | Weak |

| Exchangeable NOEs | |||||

| 28 | G305 | H1 | U306 | H3 | Strong |

| 29 | G305 | H1 | G310 | H1 | Strong |

| 30 | G305 | H1 | G310 | H21/H22 | Med/weak |

| 31 | U306 | H3 | G310 | H1 | Strong |

| 32 | U306 | H3 | G310 | H21/H22 | Med/weak |

| 33 | U306 | H3 | C311 | H41/H42 | Weak/med |

| 34 | U306 | H3 | C311 | H5 | Weak |

| 35 | G310 | H1 | C311 | H41/H42 | Weak |

| 36 | G310 | H1 | C311 | H5 | Med |

aThis NOE is weaker than expected, indicating a non-A-form structure.

bThis unusual i to i + 2 NOE indicated an unusual loop structure.

cThese intraresidue aromatic to anomeric NOEs are included here to show that a partial syn confirmation and/or conformation exchange is present for these bases.

dThis NOE is significantly stronger than expected, indicating a non-A-form structure.

Structure of the P6.1 stem–loop of human telomerase

The high degree of precision of the bundle of converged structures suggests that the loop region forms a rigid structure. This conclusion is confirmed by measurement of relaxation parameters (T1ρ) for base resonances (purine C8-H8 and Adenine C2-H2). The relaxation data reveal levels of mobility in the loop comparable to those observed in the stem region (Fig. 4), confirming that the loop forms a rather rigid structure, probably as a direct result of conformational limitation of the stretched and elongated backbone of the RNA between residues G309 and G310. The GU pair stacks above the canonical A-form stem (Fig. 3b and c), while the backbone between residues 308 and 309 is extended with the G309 phosphorus atom positioned just above the base of G310 (Fig. 3b). The backbone methylene (H5′/5″) protons of G309 also stack over the GU wobble pair, possibly stabilizing the loop structure by hydrophobic interactions. The bases of residues U307, G308 and G309 are splayed out with their Watson–Crick face pointing towards the solvent (Fig. 3c). One may have expected the phosphate of G309 to be upfield shifted from the ring current of the GU-paired bases [a phosphorus atom 4 Å above an aromatic ring would be expected to be shifted by about –0.4 p.p.m. relative to its normal chemical shift (23,24)], but it resonates instead at –3.48 p.p.m. However, the backbone is extended with several torsion angles adopting non-standard values. As is well known (25), the backbone conformation has very significant effects upon phosphorus chemical shifts and it is generally very difficult to unambiguously distinguish the two contributions to phosphorous chemical shifts (26).

Figure 4.

T1ρ relaxation parameters measured for base 1H/13C resonances of P6.1 as described previously (42). It is notable that the values observed for loop residues are only slightly higher than for stem residues, indicating that the loop structure is nearly as restricted motionally as the double helical stem.

The structure of the P6.1 loop is surprisingly reminiscent of the conformation of RNA tetraloops. The bases of U307 and G308 flank each side of the backbone in a manner reminiscent of UUCG tetraloops with an additional base bulged out (Fig. 5). There is a right-handed character to both structures as well; the angle formed by stepping from the first to the second base is roughly 220° in both loops. The step from the second base to the third is also roughly 200° in both the UUCG loop and P6.1. This dramatic turn places the third base of the loop above the first base. However, UUCG tetraloops and the present structure also have significant differences. UUCG tetraloops have a sheared GU pair formed between the first and last base, while a wobble GU pair is observed in P6.1 (Fig. 5). The extra residue G309 may allow for the formation of the U306/G310 wobble pair that requires a larger interstrand phosphate distance compared with a sheared pair. This structural arrangement is reminiscent of what has been observed in certain RNA hairpin structures, where one of the bases of a penta-loop bulges out to allow a ‘tetra-loop’-like structure to form. This has been reported for the U6 snRNA intramolecular stem–loop (27) and, most clearly, for the bacteriophage lambda box B Nut site RNA (28,29). In both cases, the fourth nucleotide of a GNR(N)A sequence bulges out to allow a structure analogous to the stable GNRA-tetra-loop to form. In the present structure, it is G309 that bulges out to allow formation of a structure reminiscent of a UUCG tetraloop to form.

Figure 5.

(a) Structure of the five loop residues from the P6.1 structure (heavy atoms only); (b) the four loop residues of the UUCG tetraloop (49). Color-coding highlights residues in analogous positioning regardless of residue type. The red residues are the 5′ uracyls from both sequences and the grey residues are at the 3′ ends of the loops.

Implications for telomerase function

The structure reported here allows a reinterpretation of the recent biochemical and genetic data regarding the function of the hTR activation domain. Foot-printing and mapping analysis (6) showed that the loop nucleotides are accessible to chemical modification in vitro according to a pattern consistent with our structure and a based paired P6.1 helix is essential for telomerase activity both in vivo and in vitro (6). Sequences that restore P6.1 pairing also restore telomerase activity, although phylogeny shows very high levels of conservation within the base paired sequence. It is unclear whether additional functional requirements besides TERT binding lead to this sequence conservation: protein contacts to both the stem and the loop of P6.1 may be required for recognition and full activation. Although the conservation of nucleotide identity prevented a conclusive phylogenetic identification of the stem–loop, the unquestionable evidence for Watson–Crick pairing presented here and the mutational data support base pairing. Our studies show in fact that this rather small stem–loop forms a well-defined structure. The conformation of the stem–loop is stabilized by a GU wobble pair and by the interactions described above within the single-stranded loop.

The exposure of the loop nucleotides in the ‘naked’ RNA indicates that our structure of P6.1 describes the TERT-free state of telomerase RNA. In fact, the pattern of nucleotide modifications changes in vivo: loop nucleotides in P6.1 exposed in the ‘naked’ telomerase RNA become protected. Protection from chemical or enzymatic digestion of course does not imply that the structure of the stem–loop changes in the assembled enzyme. Protection may be due to the bases becoming involved in RNA–RNA or protein–RNA interactions following TERT binding and RNP assembly, while the structure presented here would be conserved. In fact, the rigidity of the loop structure (Fig. 4) presented here suggests that the loop conformation may not change significantly even if the overall structure of the activation domain undergoes large changes after TERT binds to it.

The functional role of this RNA element is still puzzling but the results presented here allow us to make some specific suggestions. The observation that P6.1 forms a well-defined conformation suggests that the stem–loop may stabilize the fold of the hTR activation domain. This pre-formed structure within hTR may also be an anchor point for protein recognition or for tertiary contacts within the remainder of hTR RNA. Consistent with this proposal, mutations that preserve the loop secondary structure but change the identity of exposed nucleotides abrogate telomerase activity: although the P6.1 loop sequence is neither well conserved nor important for TERT binding, the identity of exposed loop nucleotides is essential for catalysis. Similarly, mutations that extend the stem with additional base pairs preserve TERT binding but significantly impair enzyme activity (7). The structure presented here shows that the three unpaired loop bases are bulged out and therefore available to interact with protein, RNA or DNA. We propose that the exposure of the bases allows the loop to become involved in tertiary interactions with other regions of hTR similar to tetra-loop and tetra-loop receptor interactions seen within other large catalytic RNAs. Alternatively or in addition, the loop may interact with TERT after a stable ribonucleoprotein is formed, or may interact with the newly synthesized telomeric DNA strand. These interaction(s) are very likely an essential aspect of the structural reorganization of hTR upon TERT binding.

Further insight into the stem–loop’s functional role comes from studies in lower organisms. In ciliates, a conserved stem–loop unrelated to the template domain has been shown to be essential for enzymatic activity: deletion of stem–loop IV from Tetrahymena thermophila telomerase and even mutation of certain nucleotides reduce activity (12), sometimes to <10% of wild type. Significantly, the most dramatic effects on telomerase activity occur when single nucleotides in the very apical loop of the hairpin are mutated. We propose that the apical hairpin within stem–loop IV is the Tetrahymena analog of the P6.1 stem–loop studied here and that these domains play central roles in enabling the conformational changes required for telomerase function.

How would the stem–loop studied here participate in constructing the human telomerase active site? The enzymology of telomerase is unusual. It is a reverse transcriptase that generates a long sequence of DNA repeats from a very short RNA template. During the course of the reaction, the template must shift downstream, dissociate from the nascent polymerized DNA, and present itself anew as a template for reverse transcription. In spite of the large-scale rearrangements that would be expected during this cycle of polymerization, translocation and re-initiation, this enzyme is fully processive (30). Thus, telomerase must undergo large conformational changes on a time scale similar to that of the enzymatic activity. In tetrahymena, mutations within stem–loop IV do not affect primer binding and the TERT-TR interaction is only partially destabilized but long-range effects on the folding of the template domain are observed. Stem–loop IV is very likely to participate in the formation of the active site and potentially in catalysis, with most of the activity being provided by the apical loop. Remarkably, a hairpin from the telomerase RNA from the budding yeast Kluyveromyces lactis has been proposed to play a similar functional role (11). We propose that P6.1 plays an analogous functional role in human telomerase RNA. First, we propose that P6.1 allows TERT protein to bind TR and subsequent to this interaction promotes the correct conformation of telomerase RNA. Secondly, it functions in the active site of telomerase. The exposure of loop base functional groups and the restricted structure of the loop observed here would very conceivably enable P6.1 to play a direct role in active site function, possibly in catalysis or more likely in indirectly organizing the active site. Ultimately, dissecting the function of the stem–loop will require structural insight into the telomerase holoenzyme, but this is a distant process. Before this task can be accomplished, the comparison in structure of the activation domains of distant eukaryotes may provide needed insight into the function of this essential element of telomerase.

CONCLUSIONS

The P6.1 stem–loop presented here is among the first structures to be reported from human telomerase RNA (14,15) (Fig. 1). It demonstrates that an essential and conserved sequence within the activation domain, P6.1, forms a well-defined stem–loop closed by a GU base pair. The functional importance of exposed loop nucleotides, combined with the well-defined loop structure and its similarity with other RNA loops involved in protein recognition and tertiary RNA folding, suggest that the present structure may also play a role in controlling the unusual enzymatic activity of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Future investigations will expand the structural investigation to the entire activation domain to address the detailed role that this crucial stem–loop structure plays in assembly and catalysis. The divide-and-conquer approach has been successfully used for studying the Hepatitis C IRES (31–33), the Signal Recognition Particle (34–39) and other RNPs. NMR is of course very well suited to study well-folded and stable RNA secondary structural elements. These partial structures can now be assembled to generate a structure of the entire activation domain using residual dipolar couplings (40–43). Telomerase is an area of promising anticancer research as well (44–48). Because of its essential role in telomere extension, the activation and template domains are promising new targets for the discovery of novel cancer drugs targeted to the telomerase ribonucleoprotein. The structural analysis of the activation domain will be important to elucidate the regulation of TERT activity by this essential RNA element and may ultimately permit the development of small molecules that disrupt telomerase activity in cancer cells.

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Joanna Long for assistance with spectrometer support at the University of Washington. Coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, PDB ID: 1OQ0. This work was funded in part by start-up funds from the University of Washington. Initial work on this project was conducted at MRC-LMB (Cambridge). N.L. was supported by a fellowship from the European Union.

PDB accession no. 1OQ0

REFERENCES

- 1.Lingner J. and Cech,T.R. (1998) Telomerase and chromosome end maintanance. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 8, 226–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McElligott R. and Wellinger,R.J. (1997) The terminal DNA structure of mammalian chromosomes. EMBO J., 16, 3705–3714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lingner J., Hughes,T.R., Shevchenko,A., Mann,M., Lundblad,V. and Cech,T.R. (1997) Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science, 276, 561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell J.R., Cheng,J. and Collins,K. (1999) A box H/ACA small nucleolar RNA-like domain at the human telomerase RNA 3′ end. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 567–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wenz C., Enenkel,B., Amacker,M., Kelleher,C., Damm,K. and Lingner,J. (2001) Human telomerase contains two cooperating telomerase RNA molecules.EMBO J., 20, 3526–3534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antal M., Boros,E., Solymosy,F. and Kiss,T. (2002) Analysis of the structure of human telomerase RNA in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J.L., Opperman,K.K. and Greider,C.W. (2002) A critical stem–loop structure in the CR4-CR5 domain of mammalian telomerase RNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 592–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bachand F., Triki,I. and Autexier,C. (2001) Human telomerase RNA–protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 3385–3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesmer V.M., Ford,L.P., Holt,S.E., Frank,B.C., Yi,X., Aisner,D.L., Ouellette,M., Shay,J.W. and Wright,W.E. (1999) Two inactive fragments of the integral RNA cooperate to assemble active telomerase with the human protein catalytic subunit (hTERT) in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 6207–6216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J.-L., Blasco,M.A. and Greider,C.W. (2000) Secondary structure of vertebrate telomerase RNA. Cell, 100, 503–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roy J., Fulton,T.B. and Blackburn,E.H. (1998) Specific telomerase RNA residues distant from the template are essential for telomerase function. Genes Dev., 12, 3286–3300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sperger J.M. and Cech,T.R. (2001) A stem–loop of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA distant from the template potentiates RNA folding and telomerase activity.Biochemistry, 40, 7005–7016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell J.R. and Collins,K. (2000) Human telomerase action requires two independent interactions between telomerase RNA and telomerase reverse transcriptase Mol. Cell, 6, 361–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comolli L.R., Smirnov,I., Xu,L., Blackburn,E.H. and James,T.L. (2002) A molecular switch underlies a human telomerase disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 16998–17003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theimer C.A., Finger,L.D., Trantirek,L. and Feigon,J. (2003) Mutations linked to dyskeratosis congenita cause changes in the structural equilibrium in telomerase RNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 100, 449–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Batey R.T., Battiste,J.L. and Williamson,J.R. (1995) Preparation of isotopically enriched RNAs for heteronuclear NMR. Methods Enzymol, 261, 300–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Varani G., Aboul-ela,F. and Allain,F.H.-T. (1996) NMR investigations of RNA structure. Progr. NMR Spectr., 29, 51–127. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Varani G., Aboul-ela,F., Allain,F.H.-T. and Gubser,C.C. (1995) Novel three-dimensional 1H-13C-31P triple resonance experiments for sequential backbone correlations in nucleic acids. J. Biomol. NMR, 5, 315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heus H.A., Wijmenga,S.S., van de Ven,F.J.M. and Hilbers,C.W. (1994) Sequential backbone assignment in 13C-labeled RNA via through-bond coherence transfer using three-dimensional triple resonance spectroscopy (1H, 13C, 31P) and two-dimensional hetero TOCSY. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 116, 4983–4984. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardi A. and Nikonowicz,E.P. (1992) A simple procedure for resonance assignment of the sugar protons in 13C-labeled RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 114, 9202–9203. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brünger A.T., Adams,P.D., Clore,G.M., Delano,W.L., Gros,P., Grosse-Kunstleve,R.W., Jiang,J.S., Kuszewski,J., Nilges,M., Pannu,N.S. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR system (CNS): a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piotto M., Saudek,V. and Sklénar,V. (1992) Gradient-tailored excitation for single-quantum NMR spectroscopy of acqueous solutions. J. Biomol. NMR, 2, 661–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson C.E. Jr and Bovey,F.A. (1958) Calculation of nuclear magnetic resonance spectra of aromatic hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Phys., 29, 1012–1014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wüthrich K. (1986) NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY.

- 25.Jucker F.M., Heus,H.A., Yip,P.F., Moors,E.H.M. and Pardi,A. (1996) A network of hetergeneous hydrogen bonds in GNRA tetraloops. J. Mol. Biol., 264, 968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allain F.H.-T. and Varani,G. (1995) Divalent metal ion binding to a conserved wobble pair defining the upstream site of cleavage of group I self-splicing introns. Nucleic Acids Res., 23, 341–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huppler A., Nikstad,L.J., Allmann,A.M., Brow,D.A. and Butcher,S.E. (2002) Metal binding and base ionization in the U6 RNA intramolecular stem-loop structure. Nature Struct. Biol., 9, 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scharpf M., Sticht,H., Schweimer,K., Boehm,M., Hoffmann,S. and Rosch,P. (2000) Antitermination in bacteriophage lambda. The structure of the N36 peptide-boxB RNA complex. Eur. J. Biochem., 267, 2397–2408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Legault P., Li,J., Mogridge,J., Kay,L.E. and Greenblatt,J. (1998) NMR structure of the bacteriophage lambda N peptide/boxB RNA complex: recognition of a GNRA fold by an arginine-rich motif. Cell, 93, 289–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greene E.C. and Shippen,D.E. (1998) Developmentally programmed assembly of higher order telomerase complexes with distinct biochemical and structural properties. Genes Dev., 12, 2921–2931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukavsky P.J., Otto,G.A., Lancaster,A.M., Sarnow,P. and Puglisi,J.D. (2000) Structures of two domains essential for hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site function. Nature Struct. Biol., 7, 1105–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Collier A.J., Gallego,J., Klinck,R., Cole,P.T., Harris,S.J., Harrison,G.P., Aboul-Ela,F., Varani,G. and Walker,S. (2002) A conserved structure within the HCV IRES eIF3 binding site defines a new antiviral target. Nature Struct. Biol., 9, 375–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kieft J.S., Zhou,K., Grech,A., Jubin,R. and Doudna,J.A. (2002) Crystal structure of an RNA tertiary domain essential to HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation. Nature Struct. Biol., 9, 370–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weichenrieder O., Wild,K., Strub,K. and Cusack,S. (2000) Structure and assembly of the Alu domain of the mammalian signal recognition particle. Nature, 408, 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hainzl T., Huang,S. and Sauer-Eriksson,A.E. (2002) Structure of the SRP19 RNA complex and implications for signal recognition particle assembly. Nature, 417, 767–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wild K., Sinning,I. and Cusack,S. (2001) Crystal structure of an early protein-RNA assembly complex of the signal recognition particle. Science, 294, 598–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Batey R.T., Sagar,M.B. and Doudna,J.A. (2001) Structural and energetic analysis of RNA recognition by a universally conserved protein from the signal recognition particle. J. Mol. Biol., 307, 229–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Batey R.T., Rambo,R.P., Lucast,L., Rha,B. and Doudna,J.A. (2000) Crystal structure of the ribonucleoprotein core of the signal recognition particle. Science, 287, 1232–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keenan R.J., Freymann,D.M., Walter,P. and Stroud,R.M. (1998) Crystal structure of the signal sequence binding subunit of the signal recognition particle. Cell, 94, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mollova E.T., Hansen,M.R. and Pardi,A. (2000) Global structure of RNA determined with residual dipolar couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 122, 111561–111562. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Hashimi H.M., Gosser,Y., Gorin,A., Hu,W., Majumdar,A. and Patel,D.J. (2002) Concerted motions in HIV-1 TAR RNA may allow access to bound state conformations: RNA dynamics from NMR residual dipolar couplings. J. Mol. Biol., 315, 95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Leeper T.C., Martin,M.B., Kim,H., Cox,S., Semenchenko,V., Schmidt,F.J. and Van Doren,S.R. (2002) Structure of the UGAGAU hexaloop that braces Bacillus RNase P for action. Nature Struct. Biol., 9, 397–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bondensgaard K., Mollova,E.T. and Pardi,A. (2002) The global conformation of the hammerhead ribozyme determined using residual dipolar couplings. Biochemistry, 41, 11532–11542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damm K., Hemmann,U., Garin-Chesa,P., Haule,N., Kauffman,I., Priepke,H., Niestroj,C., Daiber,C., Enenkel,B., Guilliard,B. et al. (2001) A highly selective telomerase inhibitor limiting human cancer cell proliferation. EMBO J., 20, 6958–6968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Read M., Harrison,R.J., Romagnoli,B., Tanious,F.A., Gowan,S.H., Reszka,A.P., Wilson,W.D., Kelland,L.R. and Neidle,S. (2001) Structure-based design of selective and potent G quadruplex-mediated telomerase inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 4844–4849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pruzan R., Pongracz,K., Gietzen,K., Wallweber,G. and Gryaznov,S. (2002) Allosteric inhibitors of telomerase: oligonucleotide N3′→P5′ phosphoramidates. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 559–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mergny J.L., Riou,J.F., Mailliet,P., Teulade-Fichou,M.P. and Gilson,E. (2002) Natural and pharmacological regulation of telomerase. Nucleic Acids Res., 30, 839–865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Granger M.P., Wright,W.E. and Shay,J.W. (2002) Telomerase in cancer and aging. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol., 41, 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allain F.H.-T. and Varani,G. (1995) Structure of the P1 helix from group I self splicing introns. J. Mol. Biol., 250, 333–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]