Abstract

Experimentation was initiated to explore insight into the redox-catalysis reaction derived from the heme prosthetic group of chimeric Vitreoscilla hemoglobin (VHb). Two chimeric genes encoding chimeric VHbs harboring one and two consecutive sequences of Fc-binding motif (Z-domain) were successfully constructed and expressed in E. coli strain TG1. The chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb were purified to a high purity of more than 95% using IgG-Sepharose affinity chromatography. From surface plasmon resonance, binding affinity constants of the chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb to human IgG were 9.7 x 107 and 49.1 x 107 per molar, respectively. More importantly, the chimeric VHbs exhibited a peroxidase-like activity determined by activity staining on native PAGE and dot blotting. Effects of pH, salt, buffer system, level of peroxidase substrate and chromogen substrate were determined in order to maximize the catalytic reaction. From our findings, the chimeric VHbs displayed their maximum peroxidase-like activity at the neutral pH (~7.0) in the presence of high concentration (20-40 mM) of hydrogen peroxide. Under such conditions, the detection limit derived from the calibration curve was at 250 ng for the chimeric VHbs, which was approximately 5-fold higher than that of the horseradish peroxidase. These findings reveal the novel functional role of Vitreoscilla hemoglobin indicating a high trend of feasibility for further biotechnological and medical applications.

Keywords: Vitreoscilla hemoglobin, peroxidase-like activity, Fc-binding motif, Z-domain, redox-catalysis reaction

1. Introduction

Hemoglobins are oxygen-carrying metalloprotein, which have been found in all vertebrates and some invertebrates including bacteria, fungi, and higher plants 1. These heme proteins involve various functional vitality of cells e.g. electron transfer, storage and transfer of molecular oxygen, and major metabolism of cell. Hemoglobins are considered to be superlative molecules for studying reactions of electron transfer of heme protein owing to the well-defined structure and commercial availability 2. Enzyme mechanisms among electron transporting system have been explored to provide a platform for fabricating biosensors. Construction and application of amperometric biosensors basing on molecular hemoglobins for determination of H2O2 and nitrite have extensively been reported 3-5.

Vitreoscilla hemoglobin (VHb) is an oxygen binding protein produced by the obligate aerobic bacterium Vitreoscilla sp. 6. It represents the most versatile tool for metabolic engineering of cell biotechnological processes. For circumstances, expression of VHb within various heterologous hosts (e.g. bacteria, yeasts, fungi, and plant cells), particularly under hypoxic conditions, results in enhancement of cell propagation, oxidative metabolism, antibiotic and enzyme production, and the detoxification of nitric oxide (for recent review see 7). It may also give rise to an increase yield of total proteins or intermediate metabolites and induction of bioremediation activity 8-10. The proposed function of VHb is to serve as oxygen storage trap or to facilitate oxygen diffusion to the membrane terminal oxidases 11, 12. Discovery on the consequences of VHb expression will provide a greater understanding on the functional role of VHb under oxygen-limiting conditions. Moreover, this will expand valuable information and pave the way for future applications of VHb.

Many attempts have been geared towards the evolutionary and functional significance of VHb in cellular metabolism. Expression of VHb improves the efficiency of microaerobic respiration and growth 12. Highly susceptible to killing by H2O2 has been revealed on cells-expressing VHb 13. However, little is known on the biochemical reactivity towards the heme ligands of VHb as well as other related functions. The VHb consists of two identical subunits of Mr15.8 kDa along with two protoheme IX per molecule. Protoporphyrin IX is common to P450-type cytochromes, peroxidases, catalases, and other related enzymes. Therefore, VHb is anticipated to exhibit some of the activities assigned to these enzymes 14. Supportive evidences have been drawn on the discovery of peroxidase-like activity of hemoglobins 15-17. This motivates the use of hemoglobins in place of peroxidase in many purposes e.g. water purification 18, H2O2 determination 19 and oxygen sensors 20.

To prove whether the heme prosthetic group of VHb can provide such a catalytic reaction as those obtained from the mammalian hemoglobins, the peroxidase-like activities of the purified VHbs have been tested in vitro. Herein, two chimeric VHbs carrying one and two consecutive regions of Fc-binding motif (Z-domain) have been constructed. The “Z” domain has been derived from a synthetic DNA fragment based on the sequence of the B-domain, a well-known motif of native staphylococcal protein A (SpA) that can bind specifically to the Fc portion of IgG 21. This domain has been fused to the VHb in order to i) assist one-step protein purification via IgG-Sepharose affinity chromatography, ii) create a chimeric protein possessing dual characteristics of both IgG-binding and catalytic reaction, and iii) apply as an immobilization tool to allow the correct orientation of chimeric protein on the sensor surface. The purified forms of chimeric proteins designated as ZVHb and ZZVHb have then been characterized for their IgG-binding affinities via the surface plasmon resonance as well as their peroxidase-like activities. Maximization of the peroxidase-like activities of the chimeric VHbs has been performed in comparison with those obtained from the horseradish peroxidase and bovine hemoglobin.

2. Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture

E. coli strain TG1 (supE, hsdΔ5, thiΔ(lac-proAB), F'[traD36 proAB+ lacIq lacZΔM15]) was used as host for gene cloning and protein expression. Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with ampicillin (100 mg/L) was used as a growth medium and protein expression was induced by addition of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

Enzymes and chemicals

High Fidelity Taq DNA polymerase, restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from Roche (Mannheim, Germany). All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade.

Construction of chimeric genes encoding chimeric VHbs harbouring one and two-consecutive Fc-binding motifs

DNA fragments coding for the Z and ZZ binding motifs were obtained by PCR amplification using plasmid pEZZ18 (Amersham Biosciences, Stockholm, Sweden) as template and the two primers (sense: 5′-AAAAGAATTCATGGTAGACAACAAATT

CAACAAAGAAC-3′, antisense: 5′-AAAATCTAGATTCGGCGCCTGAGCATC-3′), (MWG-Biotech AG). Since the primers contain 5′ overhang of EcoRI site in the sense and XbaI site in the antisense, therefore, the PCR products were digested with these enzymes and subsequently inserted into the VHb expression plasmid, pQVD 22. These resulted in the in-frame fusion of the Z and ZZ encoding genes at the 5′-end of the vhb gene. All cloning procedures were performed according to the standard protocol as described by Sambrook et al. 23. The newly constructed plasmids, designated pZV and pZZV, were verified for correct insertion by digestion of restriction endonucleases and further confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Purification of chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb using IgG-Sepharose affinity chromatography

E. coli cells carrying plasmids pZV and pZZV were grown for 8 hrs at 37°C with shaking at 200 rpm in 500 mL baffled flasks containing 200 mL of LB medium supplemented with 100 mg/L ampicillin. IPTG was then added to a final concentration of 1 mM and the culture was further cultivated at 25°C for 4 hrs. After harvesting by centrifugation, cells were washed and resuspended in IgG-Sepharose running buffer composed of 50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.6 (Tris-saline Tween; TST). Cell lysis was performed by ultrasonication (W380 Heat System Ultrasonic). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 15 min and the crude supernatant containing solubilized fusion protein was collected. The crude extract was filtered through the millipore filter (0.45 µm) then subsequently applied to an IgG-Sepharose (Amersham Biosceinces) column (Ø 1.0 cm, 3 mL drained gel) by gravity flow. Removal of unbound proteins was performed by washing with 10 column volumes of TST buffer followed by 2 column volumes of 5 mM NH4Ac, pH 5.0. The chimeric proteins were eluted from the column using 0.3 M acetic acid, pH 3.4. The eluted protein fraction was immediately neutralized with 0.5 M Tris, pH 10.0 and then dialysed against 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. Proteins were quantified using the Bio-Rad protein assay, based on the Bradford Coomassie blue dye-binding procedure 24.

Characterization of chimeric VHbs harbouring one and two-consecutive Fc-binding motifs

Molecular size estimation by SDS-PAGE

Protein electrophoresis was carried out in a discontinuous buffer system as described by Laemmli 25. A stacking gel (4%) and a separating gel (14%) were cast using the Mini Protean III apparatus (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Samples mixed with SDS-loading buffer were boiled at 100ºC for 10 min before applying to the gel. After complete electrophoresis was reached the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Native PAGE and activity staining

Native PAGE and activity staining were performed under non-reducing conditions. The stacking (4%) and separating gel (10%) used for electrophoresis and activity staining were prepared without addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate. Samples were mixed with loading buffer containing no reducing agent and loaded directly to the gel without heat denaturation. Immediately after electrophoresis, the gel was rinsed with deionized water and incubated for approximately 30 min in 0.1 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 containing 1% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 2 mM 1, 8-diaminonaphthalene (DAN). Hydrogen peroxide was added to a final concentration of 10 mM prior to immersion of the gel. In order to darken the DAN oxidation products, the gel was immersed in 20% trichloroacetic acid. Additionally, the color of activity stained proteins was further enhanced by counterstaining the gel with Coomassie brilliant blue dye 26.

Absorbance spectra of chimeric VHbs

UV-Vis absorption spectra of chimeric VHbs were collected using a Shimadzu spectrophotometer model 1650 (Shimadzu, Japan). Scanning of the spectra was started from 300-700 nm.

Analysis of IgG-binding affinity of chimeric VHbs harbouring one and two-consecutive Fc-binding motifs

To characterize the IgG binding capability of chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb, the interaction between the fusion proteins and human IgG was investigated in real time using the BIACORE ® 3000 instrument (Biacore AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Human purified IgG (DAKO) was utilized as an immobilized ligand and the amine-coupling procedure was performed 27. In brief, the carboxylated dextran layer of a Biacore CM5 sensor chip was activated by N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and N-ethyl-N'-(3-diethylaminopropyl)-carbodiimide (EDC). The IgG solution used for immobilization was prepared in 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.6 to a concentration of 100 nM. The immobilized response of approximately 1,800 resonance units (RU) was reached before surface deactivation using ethanolamine hydrochloride solution. Activated and deactivated of blank flow cells (without IgG immobilization) were used as reference. The chimeric proteins were diluted in HBS-P buffer (0.01 M HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.005% Surfactant P20, pH 7.4) to final concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12.5 and 6.25 nM. One hundred fifty microlitres of each diluted sample was injected at the flow rate of 30 µL/min over the immobilized IgG surface. The association and dissociation rates of ZVHb and ZZVHb to the IgG ligand were monitored and the results were displayed as sensograms. The data obtained were subsequently evaluated using the BIAevalution 3.2 software (Biacore AB). The association rate constant (ka), dissociation rate constant (kd) and affinity constant (KA) were calculated.

Analysis of peroxidase-like activity of chimeric VHbs

Peroxidase-like activity of chimeric VHbs was determined by measuring the rate of ABTS oxidation in the presence of H2O2 at ambient temperature. Formation of the oxidised product, ABTS•+, was followed spectrophotometrically at 415 nm (ε415 = 3.6 x 104 M-1cm-1). The assay mixture contained 100 µL of 50 mM ABTS, 200 µL of 0.5 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 in a total volume of 0.9 mL. The reaction was initiated by addition of 100 μL of 50 mM H2O2. The peroxidase activity of bovine hemoglobin (BHb; Sigma) was also measured for comparison.

Maximization of peroxidase-like activity of chimeric VHbs

Maximization of peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric VHbs was performed as follows:

Optimum pH for peroxidase-like activity

The peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric VHbs was measured at various pHs ranging from 3.0-8.0 using phosphate citrate buffer.

Effect of salts and buffer systems

The peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric VHbs was measured in various kinds of buffer system including Na-phosphate buffer, K-phosphate buffer, phosphate-buffered saline, HEPES buffer and phosphate citrate buffer. The pH of all the buffer systems was maintained at 7.0.

Optimum concentration of peroxide substrate (H2O2)

Various concentrations of freshly prepared H2O2 (1.25 – 80 mM) were tested in the assays of peroxidase-like activity of chimeric VHbs. Phosphate citrate buffer at pH 7.0 was used in the assay.

Optimum concentration of ABTS substrate

Various concentrations of ABTS ranging from 0.5 – 8 mM were tested. The reaction composed of 20 mM of H2O2 in phosphate citrate buffer at pH 7.0.

For further experiments, the peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric VHbs at various amounts was analyzed in phosphate citrate buffer, pH 7.0 containing 2 mM ABTS and 20 mM H2O2. The catalytic reaction was recorded at OD 405 nm at 1 minute time interval for 3 min.

3. Results and discussion

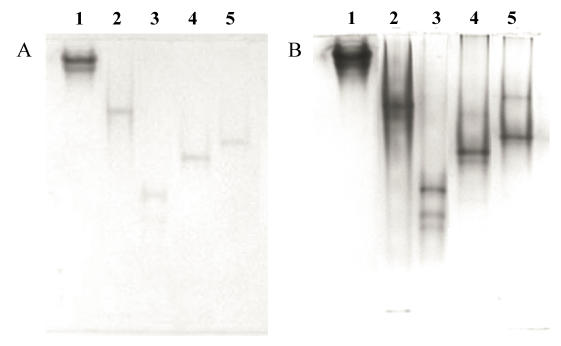

Chimeric gene construction and protein expression

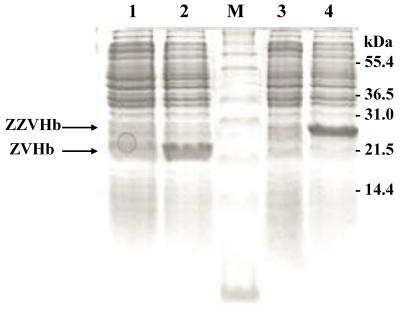

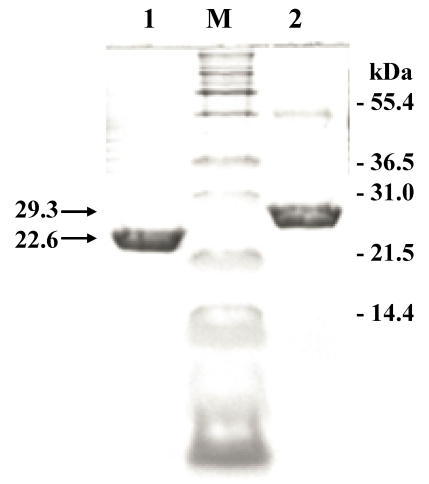

In this study, two chimeric genes encoding chimeric Vitreoscilla hemoglobin harbouring one and two-consecutive Fc-binding motifs (Z-domain) were successfully constructed and expressed in E. coli. As shown in Figure 1, a markedly increase of chimeric protein expression up to approximately 20% of total protein was found upon induction by IPTG. The chimeric proteins could be conveniently purified by IgG-Sepharose affinity chromatography yielding protein with more than 95% purity as judged by SDS-PAGE (Figure 2) using AlphaImagerTM 2200 Documentation and Analysis system (Alpha Innotech Corp, USA). The molecular weights of the purified ZVHb and ZZVHb were at 22.6 and 29.3 kDa, respectively.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE represents protein profiles of cell lysate of E. coli carrying chimeric genes of ZVHb and ZZVHb before (lane 1 and 3) and after induction by IPTG (lane 2 and 4). Two major bands at molecular masses of approx. 22 and 29 kDa are shown after induction of cells expressing chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb, respectively. M indicates molecular weight marker.

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE of the purified fraction of chimeric ZVHb (lane 1) and ZZVHb (lane 2) from IgG sepharose column M indicates molecular weight marker.

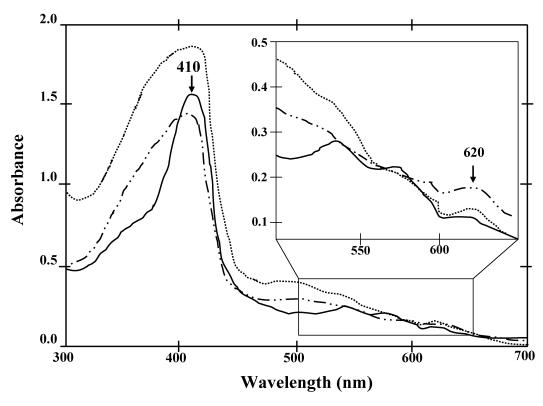

Although both of the chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb were expressed in high levels in E. coli, however, less than 10% was successfully purified. Only 1.0 mg of the chimeric protein could be obtained from a 200 mL culture. This is correspondingly due to the tendency of the VHb to form inclusion bodies as those reported previously. Results from the immunogold labeling of VHb clearly indicated a cytoplasmic localization and VHb was concentrated near the periphery of the cytosolic face of the E. coli inner membrane 28. From the absorption spectra measurements supportively demonstrated an additional peak at 620 nm beside the major peak ranged at 408-410 nm (Figure 3). The presence of major peak at 410 nm is denoted as a maximum absorption of hemoglobin. The A410/280-nm has widely been applied for estimation of VHb purity 28, 29. Meanwhile, it is conceivable that the minor peak ranged around 620 – 625 nm might be attributed to the spectra of phospholipids containing cyclopropanated fatty acids co-aggregated with VHb during the stationary phase of E. coli 30. In order to recover the VHb from insoluble fraction, attempts have been geared towards the use of denaturation agents e.g. urea and guanidine hydrochloride or detergent solubilzation 31. However, it should be noted herein that adjusting of growth condition or addition of Triton X-100 increased the amount of protein in the soluble form, but after purification the protein showed no peroxidase-like activity (data not shown). Hart and coworkers 32 have identified that the VHb expressed in E. coli in insoluble form lacks the heme prosthetic group (apoVHb) whereas the soluble form (holoVHb) contains heme in the molecule. Since the peroxidase-like activity of VHb depends on the heme group, this may explain the inactive form of ZVHb and ZZVHb in some protein portion.

Figure 3.

UV-Vis absorption spectra (300-700 nm) of the chimeric ZVHb (solid line), ZZVHb (dash-dot line) and VHb6H (VHb with hexahistidine; dot line) Inset represents the spectra with high magnification.

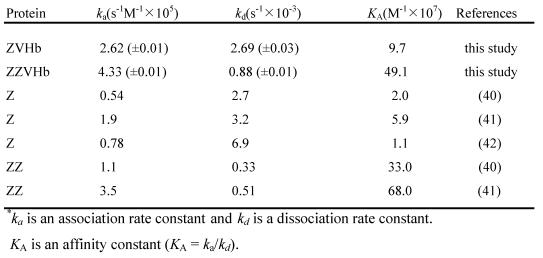

Evaluation of the kinetic parameters of ZVHb and ZZVHb binding activities to human IgG

Binding affinity to human IgG of the two chimeric proteins were investigated using the SPR biosensor. Our findings clearly showed that after being fused to VHb, the Z-domain possessed a strong binding affinity to human IgG. The kinetic parameters including the association rate constant (ka), dissociation rate constant (kd) and affinity constant (KA) were calculated as summarized in Table 1. The affinity constants to IgG of the chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb were at 9.7 x 107 and 49.1 x 107/M, respectively. These values were in the same range as those of the native Z or ZZ reported. This indicates that the Z-domain retains its native structure in the chimeric proteins.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of binding between fusion protein and human IgG*

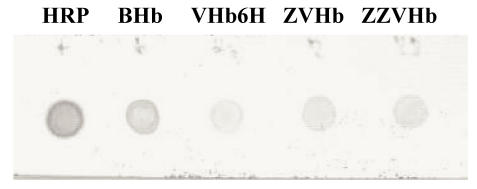

Analysis of peroxidase-like activity of chimeric VHbs

Verification of the peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb were performed using H2O2 and the reducing substrate ABTS as indicator. Specific activities for bovine hemoglobin (BHb), VHb6H (native VHb carrying an additional hexahistidine), ZVHb and ZZVHb were 0.3, 1.7, 3.9 and 1.5 unit/mg, respectively. Moreover, the peroxidase activities of the chimeric proteins could be visualized by activity staining (Figure 4) as well as by dot blotting (Figure 5), where the proteins were applied on the polyacrylamide gel and nitrocellulose membrane and directly detected with DAN substrate.

Figure 4.

Activity stain of eletrophoresis gel. The gel was loaded with 1.0 nmol of HRP, BHb, VHb6H, ZVHb and ZZVHb (lane 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, respectively). Peroxidase-like activity was detected by trichloroacetic acid enhanced DAN staining (A) without and (B) with CBB counterstained.

Figure 5.

Dot blot peroxidase-like activity Five microgram of each protein (HRP, bovine Hb, VHb6H, ZVHb and ZZVHb) was dotted on nitrocellulose membrane and allowed to dry at 4°C. The membrane was then soaked in 0.1 mM Tris, pH 8.0 containing 1% dimethyl sulfoxide and 2 mM 1,8-diaminonaphthalene (DAN). A chimeric H6GFPZ was applied as a negative control (data not shown). H2O2 was added to a final concentration of 10 mM.

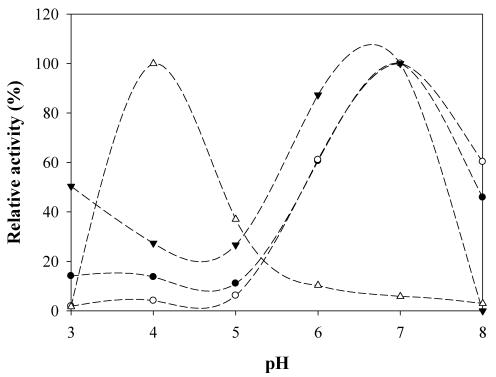

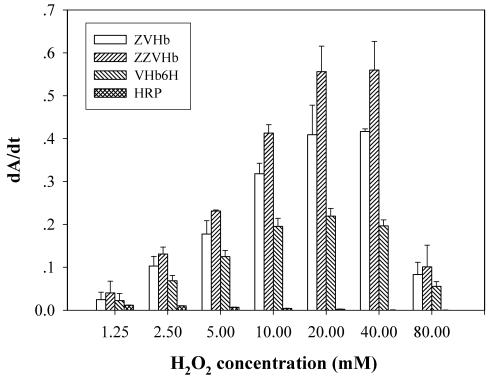

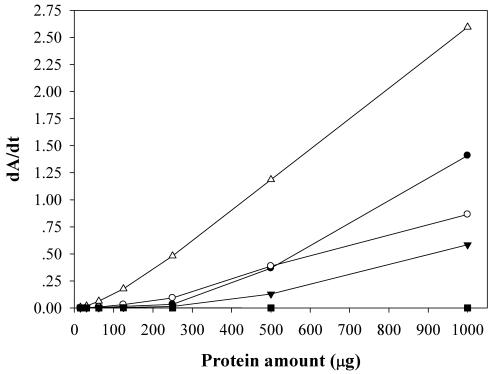

To maximize the peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric VHbs, various parameters including the effect of pH, effect of salts and buffer systems, concentrations of H2O2 and ABTS were applied into the assay reaction. Figure 6 illustrates that the pH optimum for the peroxidase-like activity of all the chimeric VHbs was approximately 7.0 while the HRP was shown to exhibit the highest activity at pH around 4.0. The phosphate citrate buffer at pH 7.0 was proven to provide a greater extent for the peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric VHbs. A gradual increase of activity correspondingly to the concentrations of hydrogen peroxide (up to 20 and 40 mM) was found in the case of chimeric VHbs (ZVHb and ZZVHb, Figure 7). Contrarily, for HRP, our results advocate the former finding that increase concentration of H2O2 substrate markedly suppressed the peroxidase activity 33. Among these parameters, the optimum concentration of ABTS was found to be at 2 mM to generate the highest activity. Therefore, varied amounts of chimeric VHbs were conducted for peroxidase activity under the optimum condition to generate the enzyme response curve as represented in Figure 8. The peroxidase-like activities for the chimeric VHbs were in the order of ZVHb > ZZVHb > VHb6H. The detection limits were down to 250 and 50 ng for the chimeric ZVHb or ZZVHb and HRP, respectively. Notification has to be made that the HRP provides 5-fold higher sensitivity than those of the chimeric VHbs.

Figure 6.

Peroxidase-like activity of chimeric ZVHb (closed circle), ZZVHb (opened circle), VHb6H (closed triangle) and HRP (opened triangle) at different pHs

Figure 7.

Analysis of peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric ZVHb, ZZVHb, VHb6H and HRP in the presence of various concentrations of hydrogen peroxide. The derivative of Absorption (A) as a function of time (t) is represented by dA/dt.

Figure 8.

Enzyme-response curve of the peroxidase-like activity of ZVHb (closed circle), ZZVHb (opened circle), VHb6H (closed triangle), HRP (opened triangle) and H6GFPZ (square; applied as a negative control). The derivative of Absorption (A) as a function of time (t) is represented by dA/dt.

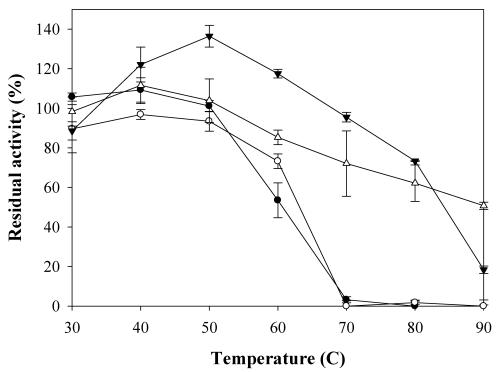

To investigate the physical stability of the chimeric VHbs, effects of heat treatment on the peroxidase-like activity were tested. The ZVHb, ZZVHb, VHb6H and bovine Hb were diluted to a concentration of 10 µM in Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and the protein solutions were then subjected to heat treatment at various temperatures ranging from 30 to 90°C for 10 min and immediately cooled down on ice. The percentage of remaining peroxidase activities of these proteins were then determined (Figure 9). Our results revealed that the activity of VHb6H could be enhanced up to 135% when the protein was treated at 50°C for 10 min and the protein retained more than 70% activity after heating to 80°C. In the case of bovine hemoglobin, the activity was mostly enhanced at 40°C and it retained more than 60% activity after heated up to 80°C. For the chimeric proteins, the peroxidase-like activities were slightly increased in the case of ZVHb but not in ZZVHb, after heating the proteins, and totally disappeared when the proteins were heated up to 70°C. However, the ZVHb and ZZVHb retained nearly 100% activity after heating at 50°C.

Figure 9.

Percentage of residual peroxidase-like activity of ZVHb (closed circle), ZZVHb (opened circle) VHb6H (closed triangle), and BHb (opened triangle) after heat treatment at various temperatures for 10 min. The values are mean values of triplicate measurements and the error bars indicate standard deviations.

According to the previous studies, the structure of heme proteins has been found to be affected by heat treatment or denaturing agents. Diederex et al 34 have recently reported on the increase of peroxidase activity of cytochrome c upon addition of guanidine hydrochloride. Chattopadhyay 35 and his colleagues have demonstrated the conformational changes of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) by the effects of temperature and pH. By circular dichroism and fluorescence studies, they have concluded that at neutral pH, changes of the tertiary structure around the heme pocket occurred at the temperature range of 40-50°C while the overall secondary structure of the enzyme remained non-significant change. However, at higher temperature (Tm = 74°C), the heme was completely removed from the enzyme active site. Moreover, acidity caused the splitting of the hemes from the apoproteins as indicated by the drop of their soret bands in methemoglobin 15. Interestingly, the VHb6H and BHb give rise to more pronounced activity to heat enhancement than those of the ZVHb and ZZVHb. Since peroxidase activity of hemoglobin is also based on the prosthetic heme group, the enhancement of specific activity upon heat treatment is probably due to the rearrangement of tertiary structure nearby the heme pocket resulting in unmasking of the heme pocket to the environment.

Conclusion and future perspectives

New insight into the catalytic reaction based on heme-prosthetic group of the Vitreoscilla hemoglobin (VHb) has been firstly revealed in this study. The peroxidase-like activity of the chimeric VHbs carrying the Fc-binding motif has been attained. This novel function opens up a high feasibility to further apply the chimeric VHb in biotechnological and medical approaches. The chimeric ZVHb and ZZVHb can further be accessed as a secondary antibody-peroxidase conjugate in various types of immunoassay. Since the peroxidase is widely used to tag the secondary antibody in enzyme immunoassays. Detection signal can be generated from a wide variety of chromogenic substrates. The development of HRP-labeled SpA based on chemical conjugation has earlier been reported by Zhou et al 36. However, the chemical reaction is complicated and degree of conjugation is hardly controlled. Titration or validation is required due to batch to batch variation. In addition, expression of native HRP in bacteria is intrinsically difficult on the account of the high tendency to form inclusion bodies 37. Meanwhile, conjugation via gene fusion generates exact chimeric protein of the fusion partners. The chimeric VHbs possess both the peroxidase-like activity and the IgG-binding affinity precisely as gene-engineered design. Although the activity of the chimeric VHbs after maximization is 5-fold lower than that of the HRP. This in turn provides more advantages on the lowering background interference as compared to the HRP while augmenting an appropriate sensitivity for the detection. Interestingly, an optimum activity of the VHb is catalyzed on the high level of peroxide substrate which either of endogenous peroxidase or the HRP can be negligible 33. Our findings lend support the high feasibility of using the chimeric VHbs in immunohistochemistry purposes. To further expand their applicability in other types of immunoassay, site-directed mutagenesis can then be applied to create mutation on the heme-neighbouring residues in order to achieve a higher catalytic mutant 38, 39. Furthermore, the chimeric VHbs can be incorporated on to the sensor surface via the IgG-binding interaction and applied as an electrochemical-redox sensor for biotechnological applications in the future 20.

Acknowledgments

Y.S. was supported by the collaborative Ph.D. fellowship from Royal Thai government and N.T. was supported by the Royal Golden Jubilee Ph.D. scholarship from the Thailand Research Fund under the supervision of V.P. M.K. was Ph.D. student supported by Lund University. This project was partially supported by a governmental grant under Mahidol University (annual 2546-2550 B.E.).

References

- 1.Hardison R. Hemoglobins from bacteria to man: Evolution of different patterns of gene expression. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:1099–117. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.8.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou B, Sun R, Hu X, Wang L, Wu H, Song S. et al. Facile interfacial electron transfer of hemoglobin mediated by conjugated polymers. Int J Mol Sci. 2005;6:303–10. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma X, Liu X, Xiao H, Li G. Direct electrochemistry and electrocatalysis of hemoglobin in poly-3-hydroxybutyrate membrane. Biosens Bioelectron. 2005;20:1836–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sun W, Jiang S, Jiao K. Electrochemical determination of hydrogen peroxide using o-dianisidine as substrate and hemoglobin as catalyst. J Chem Sci. 2005;117:317–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang W, Bai U, Li Y, Sun D. Amperometric nitrite sensor based on hemoglobin/colloidal gold nanoparticles immobilized on a glassy carbon electrode by a titania sol-gel film. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;382:44–50. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3160-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webster DA, Hackett DP. The purification and properties of cytochrome o from Vitreoscilla. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:3308–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frey AD, Kallio PT. Nitric oxide detoxification - a new era for bacterial globins in biotechnology? Trends Biotechnol. 2005;23:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kallio PT, Bailey JE. Intracellular expression of Vitreoscilla hemoglobin (VHb) enhances total protein secretion and improves the production of alpha-amylase and neutral protease in Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol Prog. 1996;12:31–9. doi: 10.1021/bp950065j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu JM, Hsu TA, Lee CK. Expression of the gene coding for bacterial hemoglobin improves beta-galactosidase production in a recombinant Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Lett. 2003;25:1457–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1025072020791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung JW, Webster DA, Pagilla KR, Stark BC. Chromosomal integration of the Vitreoscilla hemoglobin gene in Burkholderia and Pseudomonas for the purpose of producing stable engineered strains with enhanced bioremediating ability. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;27:27–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber RE, Vinogradov SN. Nonvertebrate hemoglobins: Functions and molecular adaptations. Phys Rev. 2001;81:569–628. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai PS, Nageli M, Bailey JE. Intracellular expression of Vitreoscilla hemoglobin modifies microaerobic Escherichia coli metabolism through elevated concentration and specific activity of cytochrome o. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1996;49:151–60. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960120)49:2<151::AID-BIT4>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geckil H, Gencer S, Kahraman H, Erenler SO. Genetic engineering of Enterobacter aerogenes with the Vitreoscilla hemoglobin gene: cell growth, survival, and antioxidant enzyme status under oxidative stress. Res Microbiol. 2003;154:425–31. doi: 10.1016/S0923-2508(03)00083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukai M, Mills CE, Poole RK, Yeh SR. Flavohemoglobin, a globin with a peroxidase-like catalytic site. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7272–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009280200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inada Y, Kurozumi T, Shibata K. Peroxidase activity of hemoproteins. I. Generation of activity by acid or alkali denaturation of methemaglobin and catalase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1961;93:30–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(61)90311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith MJ, Beck WS. Peroxidase activity of hemoglobin and its subunits: effect thereupon of haptoglobin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967;147:324–33. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(67)90410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chung J, Wood JL. Oxidation of thiocyanate to cyanide catalyzed by hemoglobin. J Biol Chem. 1971;246:555–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matcham GWJ, Chapsal JM, Guillochon D. Catalytic activities of bovine hemoglobin. Enzyme Eng. 1987;501:21–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb45680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang K, Mao L, Cai R. Stopped-flow spectrophotometric determination of hydrogen peroxide with hemoglobin as catalyst. Talanta. 2000;51:179–86. doi: 10.1016/s0039-9140(99)00277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan C, Zhong J, Guan R, Li G. Direct electrochemical characterization of Vitreoscilla sp. hemoglobin entrapped in organic films. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1649:123–36. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(03)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nilsson B, Moks T, Jansson B, Abrahmsen L, Elmblad A, Holmgren E. et al. A synthetic IgG-binding domain based on Staphylococcal protein A. Protein Eng. 1987;1:107–13. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roos V, Andersson CIJ, Arfvidsson C, Wahlund KG, Bulow L. Expression of double Vitreoscilla hemoglobin enhances growth and alters ribosome and tRNA levels in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Prog. 2002;18:652–6. doi: 10.1021/bp020005v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoopes JT, Dean JFD. Staining electrophoretic gels for laccase and peroxidase activity using 1,8-diaminonaphthalene. Anal Biochem. 2001;293:96–101. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loefas S, Johnsson B, Edstrom A, Hansson A, Lindquist G, Hillgren RM. et al. Methods for site controlled coupling to carboxymethyldextran surfaces in surface plasmon resonance sensors. Biosens Bioelectron. 1995;10:813–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramandeep D, Hwang KW, Raje M, Kim KJ, Stark BC, Dikskit KL. et al. Vitreoscilla hemoglobin. Intracellular localization and binding to membranes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24781–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009808200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramandeep D, Pathania R, Sharma V, Mande SC, Dikshit KL. Chimeric Vitreoscilla hemoglobin (VHb) carrying a flavoreductase domain relieves nitrosative stress in Escherichia coli: new insight into the functional role of VHb. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:152–160. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.1.152-160.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rinaldi A, Bonamore A, Macone A, Boffi A, Bozzi A, Di Giulio A. Interaction of Vitreoscilla Hemoglobin with Membrane Lipids. Biochemistry. 2006;5:4069–76. doi: 10.1021/bi052277n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hart RA, Bailey JE. Solubilization and regeneration of Vitreoscilla hemoglobin isolated from protein inclusion bodies. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1992;39:1112–20. doi: 10.1002/bit.260391106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hart RA, Kallio PT, Bailey JE. Effect of biosynthetic manipulation of heme on insolubility of Vitreoscilla hemoglobin in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2431–7. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2431-2437.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nazari K, Mahmoudic A, Khodafarinb R, Moosavi-Movahedia A, Mohebi A. Stabilizing and suicide-peroxide protecting effect of Ni2+ on horseradish peroxidase. J Iranian Chem Soc. 2005;2:232–7. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diederex REM, Ubbink M, Canters GW. Effect of the protein matrix of cytochrome c in suppressing the inherent peroxidase activity of its heme prosthetic group. ChemBioChem. 2002;1:110–2. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020104)3:1<110::AID-CBIC110>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chattopadhyay K, Mazumdar S. Structural and conformational stability of horseradish peroxidase: Effect of temperature and pH. Biochemistry. 2000;39:263–70. doi: 10.1021/bi990729o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou H, Gong Z, Baiying Q, Honghai W, Xiaoping Z. A simple periodate method for the horseradish peroxidase labeled staphylococcal protein A. Weishengwuxue Tongbao. 1986;13:171–3. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levy I, Shoseyov O. Expression, refolding and indirect immobilization of horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to cellulose via a phage-selected peptide and cellulose-binding domain (CBD) J Pept Sci. 2001;7:50–7. doi: 10.1002/psc.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dikshit KL, Orii Y, Navani N, Patel S, Huang HY, Stark BC. et al. Site-directed mutagenesis of bacterial hemoglobin: the role of glutamine (E7) in oxygen-binding in the distal heme pocket. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1998;349:161–6. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verma S, Patel S, Kaur R, Chung YT, Duk BT, Dikshit KL. et al. Mutational study of the bacterial hemoglobin distal heme pocket. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:290–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nilsson J, Nilsson P, Williams Y, Pettersson L, Uhlen M, Nygren PA. Competitive elution of protein A fusion proteins allows specific recovery under mild conditions. Eur J Biochem. 1994;224:103–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tashiro M, Montelione GT. Structural of bacterial immunoglobulin-binding domains and their complexes with immunoglobulins. Curr Opin Struc Biol. 1995;5:471–81. doi: 10.1016/0959-440x(95)80031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gulich S, Uhlen M, Hober S. Protein engineering of an IgG-binding domain allows milder elution conditions during affinity chromatography. J Biotechnol. 2000;76:233–43. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(99)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]