Dealing with a cancer diagnosis and cancer treatment involves communication among clinicians, patients, families, friends and others affected by the illness. The hypothesis of this research is that an informatics system can effectively support the communication needs of cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Two design frameworks for online cancer communication are defined and compared. One is centered primarily on the users’ interpersonal relationships, and the other is centered on the clinical data and cancer information. Five types of clinical and supportive relationships were identified and supported by in-depth interviews with cancer patients and their informal caregivers. Focusing the design of an online cancer communication system around the interpersonal relationships of patients and families may be an important step towards designing more effective paradigms for online cancer care and support.

Introduction

Patient-controlled Personal Health Records (PHRs) and patient-provider communication systems are recognized as essential components of emerging web-based paradigms for patients’ involvement in the management of their own health care.1 Web-based information and communication systems for cancer patients have demonstrated that personalized, interactive systems can increase the patients’ confidence in their care and improve social support.2 However, a review of online cancer patient support groups found that the existing research is inconclusive about significant overall benefits of online cancer communities.3

Dealing with the diagnosis of cancer and managing the treatment involves complex and very personal information and communication needs among clinicians, patients, families, friends and others affected by the illness.4 Because of these complex needs, recent treatment plans for cancer aim to focus on the patient as a whole, involving components for physical, emotional, spiritual, and social care and support.5 In practice, many of these needs still are unmet by health-care providers.6

The subtle aspects of holistic cancer care and communication must be handled in emerging online cancer communication systems in order to achieve the highest quality standard of care in an online environment. Clinical and supportive systems have begun to address the online communication needs of patients and families, but novel design approaches are needed to fully realize the potential of holistic care features in online cancer communication.

Two design frame works are defined and compared. One is centered primarily on the users’ interpersonal relationships, and the other is centered on the clinical data and cancer information.

Two Design Frameworks

Relationship-centric design

Relationship-centric design follows two principles:

Interpersonal relationships between the users are the basic units around which all other components in the design are framed.

The social influences in the relationships are understood and are addressed in the design.

The emphasis in this design is on the individuals and groups using the system and how they interact in their relationships. The relationships might exist entirely within the online system, or they may continue offline through in-person and telephone-based communication. Relationship-centric design seeks to understand the roles and influences of the people who share information on the system. The information content on the system is represented within the context of these relationships.

Information-centric design

Information-centric design stresses the information exchanged, with minimal emphasis on the relationships between the users. This approach follows the general principle:

The information and structured content are the basic units around which all other components in the design are framed.

The highly-structured requirements of sharing medical data, symptom tracking, medication lists, and other records may lead developers to create a design that centers on each user’s information needs. This is representative of an information-centric design. Relationship-centric design does not ignore these needs; rather, it attempts to satisfy them in context of the social influences between/among the users.

Relationship-centric design and information-centric design are not mutually exclusive frameworks for online communication systems. An information-centric design is, in a sense, a relationship-centric design that is stripped of all interpersonal associations between the users. A design becomes more relationship-centric as more emphasis is placed on the users’ interpersonal relationships. This balance between the users’ relationships and the information content relates to Coiera’s work on the critical interplay between communication and information in an organization’s clinical information system.7 Relationship-centric design expands upon the notion of communication-centric design by more actively addressing the social influences that shape the communication in each user’s personal relationships.

Why use a relationship-centric design for online cancer communication?

The fundamental concepts of relationship-centric design are informed by the field of social psychology. Social psychology is defined as “the scientific study of the way in which people’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors are influenced by the real or imagined presence of others.”8 Social norms and other pressures directly and indirectly influence interpersonal actions in the real-world. Suler suggests that well-studied social psychology principles can be applied to the study of online communities and new principles of social psychology may be created to address the uniqueness of online relationships.9 In cancer communication, for example, a patient might not ask a provider for pain medicine if he or his family fears an addiction or if he wants to be a ‘good’ patient in the patient-provider relationship.10 A relationship-centric design incorporates an understanding of why the patient is not asking his provider for pain medicine, whereas a purely information-centric design will provide only structured interfaces for the user to request medication.

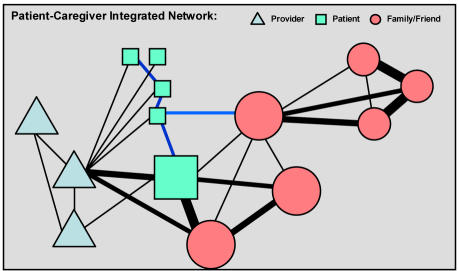

The cancer patient and family face the illness in the context of their existing responsibilities and relationships. Given and Given argue for the use and creation of more family-focused care plans for cancer treatment.4 The unique communication and support needs suggest that an online communication system for cancer care should not neglect the holistic aspects of the in-person care and support. Figure 1 illustrates the clinical and social relationships of a cancer patient, primary caregiver, family and friends, and fellow patients. A relationship-centric design for holistic cancer communication will address each of these relationships as desired by the patient.

Figure 1.

Patient-Caregiver Integrated Network. The thickness of the lines represents the complexity and uniqueness of each relationship.

Research Methodology

The research methodology for the entire study will consist of three major phases. Phase I focuses on understanding the communication needs of the cancer patients and caregivers. Phase II will be the design of the system and Phase III will be field testing the system. This paper covers only the interview portion of the initial assessment phase that provided the context for the design of the system (Phase II).

Patient and Caregiver Interviews

Semi-structured, 30–60 minute interviews were conducted over the course of one week with sixteen patients receiving chemotherapy in the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center clinic. There were no follow-up interviews. Nine of the sixteen patients had a family or friend caregiver who participated in the interview. The patients were all adults with various cancer diagnoses, including head and neck, lung, and breast cancers. The interviews focused on communication needs with the clinic (e.g. “Describe the practical challenges of keeping track of your/the patient’s pain or symptoms at home.”), clinical and supportive communication needs with family and friends (e.g. “Describe the methods you use to keep family and friends informed of how you and the patient are doing.”), and general use and interest in the Internet for cancer communication (e.g. “About what do you send/receive messages online?”). Saturation was reached after sixteen interviews.

Results

The interviews were transcribed and were coded into 73 non-hierarchical concept nodes with the N6 software package using a modified grounded theory methodology. Five types of clinical and supportive relationships were identified from the concepts, which were labeled based on topics mentioned and descriptive characteristics of each interview response. These five classes of relationships are Clinical, Explicit Supportive, Implicit Supportive, Private- Open, and Holistic relationships. For each relationship, information-centric and relationship-centric designs are compared as to how they would-wouldn’t address the communication needs.

Clinical Relationships

Informal family and friend caregivers are involved actively in the patient’s clinical care both at home and during the clinic visits.4 A patient’s brother visiting from out of town described how he has been active in the clinical care:

About the time he was finishing up his treatments that made me think we had missed some instructions during that period of time, because it didn’t seem like we were fully compliant. […] Well, I came back, and we asked a lot of questions, and we made some notes and found out exactly what he should be doing for his nutrition, got him on a schedule. And, so he has his schedule, and he does that for himself now.

From an information-centric approach, the focus of the provider’s patient communication system is on providing treatment information, structured symptom tracking and decision support, patient education, and responding to the patients’ questions. The patients may be sharing this information or getting advice from family and friends regarding the questions they ask, but these informal consultations are not facilitated or documented in the clinical messaging system.

In a relationship-centric design, the goal of the clinical communication is to appropriately include all people that the patient defines as partners in his or her clinical care and to understand what type of clinical communication is involved in each of these relationships. Who needs to know every detail of the clinical care in monitoring and assisting with the home care? With whom do the patients and primary caregivers consult for certain types of assistance?

Detailed information, provider messaging, and tools for symptom tracking and decision support all may be included in the design of the system. But, in a relationship-centric approach, these components are designed to include and support all of the formal and informal relationships that the patient chooses to involve in each clinical activity. For example, the design could include conversation spaces shared by the patient, selected family members, and the clinic’s nutritionist, social worker, and/or spiritual nurse.

Explicit Supportive Relationships

Family and friends directly support the patient in many of the non-clinical communication needs associated with facing the illness and receiving cancer treatment.4 This may include practical support such as arranging rides to the clinic visits and running errands. Family communication also may involve active emotional support, such as visiting the patient in the home and listening to the patient’s concerns. Family and friends also may provide informational support, such as helping the patient or primary caregivers find information about cancer, treatment options, side effects, or other general resources.

Much of the literature on supportive cancer care provides examples of explicit support, and the patients and/or caregivers in each interview provided personal examples of this support from family, friends, and also from other patients. Studies of existing online cancer support groups have found that messages shared are related to emotional and social support as well as to the exchange of clinical information.11

A relationship-centric cancer communication system would include the family and friends who have supportive relationships with the patient, even if they do not have active clinical relationships with the patient or the clinic team. The patient still has communication needs with these family members and friends. A relationship-centric design would address the communication needs of the family’s clinical relationships while not ignoring the context of the supportive communication needs, and vice versa. An information-centric design would not attempt to deal with the overlaps and influences between the clinical and non-clinical relationships.

Implicit Supportive Relationships

Implicit supportive relationships refer to the perceived presence of family, friends, fellow patients, and providers; a sense of support during the times that they aren’t engaged in explicit support and communication. Eight (50%) of the interviewed patients and caregivers described their supportive relationships as ‘knowing that they’re there,’ even when there is no current need for active support:

“That’s really the important thing […] especially with families, you know, they care and they are interested […]”

“Well, we know, when we ask, they will come. That’s the kind of friends that we have.”

Information-centric designs and relationship-centric designs will differ in their approaches to addressing these implicit communication needs in the online system. Perceived presence of support does not involve the sharing of any hard data, so an information-centric framework may pass over these subtle aspects of supportive communication.

A relationship-centric design would incorporate the essence of these silent and implied interactions into many interfaces throughout the communication system. Understanding and incorporating aspects of the relationships that cannot easily be expressed in words is fundamental to the relationship-centric design framework.

One of the interviewed patients created her own public web site on which she shared her treatment news and family updates. She looked into putting a visit counter on her site, “because I really would love to know, how many people are going out there.” The feedback of knowing that someone is listening, which occurs during in-person and telephone-based conversations, is not a standard in most web-based communications. The implicit support of the listener can play an essential role in the two-way relationship, and providing an indication of this activity to the patient online could be done in many simple and creative ways. In an information-centric design, this type of feedback may be a nice feature to include for receipt confirmation, but in a relationship-centric design this type of feedback is tightly integrated with each component of the system. For instance, the names and pictures of recent visitors to the patient’s web site could be displayed at each patient login.

Private and Open Relationships

During the interviews, each patient expressed unique privacy needs regarding communication about his or her illness. All of the patients and caregivers were open about their well-being and general treatment information with most family and friends who expressed interest. Three patients (19%) shared information with friends but kept details from certain family members. One patient said she would not mind if her children asked questions to the doctor if they did not feel comfortable asking her directly. As a whole, the patients have unique inclusion and exclusion criteria for sharing different details with different individuals and groups. Also, patients, family members, and friends may desire to share more emotional messages in a private setting, whereas they don’t mind sharing general supportive messages in a more open, public setting.

An information-centric design will focus mainly on the patient’s data and may not fully address the different levels of privacy or openness in which the information is shared. A relationship-centric design will provide a means for the patient to selectively share the information in ways that are appropriate for each individual and group relationship. Research in Personal Health Records involves this aspect of relationship-centric design.12 The patient is given control over who can view and access his or her information stored in the record, based on the requesting user’s identity, role, or other relation to the patient. This user-defined control of sharing personal information typically refers to the exchange of Protected Health Information with health care providers. In addition to giving the patient control over clinical information, an analogous approach can allow the patient to selectively share certain emotional and personal messages with friends, family, and others.

Holistic Relationships

The interviews provided several examples of ways in which communication about to the illness blends with the context of the patients’ daily lives.

The daughter of one patient keeps a notebook in which she records how her mother is feeling, what has occurred in the clinic, and what to expect related to her mother’s treatment. The daughter also uses the same notebook to keep a journal for herself about her own life. For her, there is no real distinction between her clinical notes and her personal notes,

It's my journal. It's my composition, what goes on with my life, just different things that happen. […] my whole life, this is my journal, and she's my life.

An information-centric design might provide an area for clinical messages and journals, but it would not address this relationship between the clinical information and the patient’s or caregiver’s need to record and/or share other types of personal information alongside the clinical notes.

Another patient explained that she uses the phone to update her family on her treatment, and she added,

But still, you know, we could talk about other things, instead of all of this. I mean, don’t get me wrong, this is important, and it’s really a big factor in my life, but it’s not the only thing I want to talk about. So if I just would cover the other [online], and then if the doctor has a specific something or other that needs to be shared with the family, you know, that could be done too.

Even though many of the patient’s communication needs may focus on cancer, she does not want this communication to overshadow and take away from the other meaningful aspects of her relationships. She suggests that if she could share some of the clinical discussions online, she would have to repeat herself less often and have more time to talk about other topics with her family.

But online clinical communication may produce unintended effects on the patient’s non-clinical, social relationships. The patient who created her own web site mentioned concerns that apart from her immediate family, it seems like people tend just to read the web site, and they do not call her to talk on the telephone as much as she would like.

When an online communication system is introduced, the default, most convenient mode of communicating with the patient may change, even if this is not desirable for the patient at all times. It is important to design the cancer communication system so that it does not inadvertently impact other aspects of a patient’s relationships in a negative manner. An information-centric design would aim to share the primary treatment news efficiently, while a relationship-centric design would attempt to recognize how the online clinical communication affects other aspects of the patient’s interpersonal interactions.

Discussion

One design of a patient-provider messaging system is to center the communication channels on the relationships and communication needs of the providers, where communication with the patient is one of those connections. The patient is viewed as an isolated end-user in the clinical system, rather than as a person with relationships and influences outside of the clinic team. This design may be a natural model for a health care organization’s existing clinical information system, but it does not accurately represent the patient’s communication needs in the broad context of his or her illness.

Another way to design the system is to center it on each patient, where the health care provider is one of the several communication channels utilized by the patient. In this design, it is critical for the providers to actively participate in the communication system, because they are a main partner in the patient’s care. The providers must also recognize and address the fact that the patient and family have other communication needs and influences during the illness. This design may involve collaborations within or outside of the health care system, and it is a natural and necessary strategy for cancer communication systems to fully address all of the patients’ communication needs.

Relationship-centric design can inform the development of a communication system for cancer patients with two distinctive characteristics:

Each user has the option to invite and define relationships and privacy with his or her own family and friends

The system includes various forms of implicit feedback with both clinical and non-clinical communication between providers, patients, and family/friends

Conclusion

Relationship-centric design for online cancer communication has the potential to help developers create new paradigms that better reflect the broad network of care and the holistic nature of in-person cancer care and support. Developers of cancer communication systems, and perhaps developers of all patient communication systems, should attempt to address more of the patients’ outside relationships that may influence or be affected by the online clinical communication with the health care team.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Training Grant from the National Library of Medicine (T15 LM 007450-03). The study was approved by the IRB.

References

- 1.Brennan P, Safran C. Report of conference track 3: patient empowerment. Int J Med Inf. 2003;69(2–3):301–4. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(03)00002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW, et al. CHESS: 10 years of research and development in consumer health informatics for broad populations, including the underserved. Int J Med Inf. 2002;65(3):169–177. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(02)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eysenbach G, Powell J, Englesakis M, Rizo C, Stern A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. BMJ. 2004;328(7449):1166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Given BA, Given CW, Kozachik S. Family support in advanced cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2001;51(4):213–31. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.51.4.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Twycross RG. The challenge of palliative care. Int J Clin Oncol. 2002;7(4):271–8. doi: 10.1007/s101470200039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osse BH, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Schade E, Grol RP. The problems experienced by patients with cancer and their needs for palliative care. Support Care Cancer. 2005 Feb 9; [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277–86. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aronson E, Wilson TD, Akert RM. Social Psychology. 5th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2005.

- 9.Suler J. (1996). Applying social-psychology to online groups and communities. In The Psychology of Cyberspace. www.rider.edu/suler/psycyber/socpsy.html (article originally published 1996)

- 10.Ward S, Hughes S, Donovan H, Serlin RC. Patient education in pain control. Support Care Cancer. 2001;9(3):148–55. doi: 10.1007/s005200000176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klemm P, Bunnell D, Cullen M, Soneji R, Gibbons P, Holecek A. Online cancer support groups: a review of the research literature. Comput Inform Nurs. 2003;21(3):136–42. doi: 10.1097/00024665-200305000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandl KD, Szolovits P, Kohane IS. Public standards and patients' control: how to keep electronic medical records accessible but private. BMJ. 2001;322(7281):283–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7281.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]