Abstract

The modification of nucleic acids using nucleotides linked to detectable reporter or functional groups is an important experimental tool in modern molecular biology. This enhances DNA or RNA detection as well as expanding the catalytic repertoire of nucleic acids. Here we present the evaluation of a broad range of modified deoxyribonucleoside 5′-triphosphates (dNTPs) covering all four naturally occurring nucleobases for potential use in DNA modification. A total of 30 modified dNTPs with either fluorescent or non-fluorescent reporter group attachments were systematically evaluated individually and in combinations for high-density incorporation using different model and natural DNA templates. Furthermore, we show a side-by-side comparison of the incorporation efficiencies of a family A (Taq) and B (VentR exo–) type DNA polymerase using the differently modified dNTP substrates. Our results show superior performance by a family B-type DNA polymerase, VentR exo–, which is able to fully synthesize a 300 bp DNA product when all natural dNTPs are completely replaced by their biotin-labeled dNTP analogs. Moreover, we present systematic testing of various combinations of fluorescent dye-modified dNTPs enabling the simultaneous labeling of DNA with up to four differently modified dNTPs.

INTRODUCTION

DNA modifications through nucleotides linked to detectable reporter or functional groups have a variety of potential applications in modern molecular biology and medicine. Several detectable reporter groups such as digoxigenin, biotin and fluorophores are widely used as experimental tools in nucleic acid modification. In particular, fluorescent nucleic acid probes are a crucial part in many techniques such as fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) (1,2), monitoring of gene expression (3,4), single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis (5) and DNA sequencing (6,7). In addition, the catalytic repertoire of nucleic acids can potentially be expanded through incorporation of various functional groups linked to nucleotides followed by selection using the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) technique (8,9). Alternatively, new DNA sequencing approaches based on the detection of fluorescent dye-tagged nucleotides cleaved from a single fluorescent labeled DNA molecule substrate have been proposed (10,11). Unlike conventional DNA sequencing, base-specific labeling of every position in the target sequence replica using fluorophore-labeled nucleotides is obligatory in this case (10,11). Modified nucleic acid reagents are an important component of the above applications, and in some cases the incorporation of appropriately modified nucleotides into DNA at a high density is required. The efficient and base-specific replacement of natural deoxyribonucleoside 5′-triphosphates (dNTPs) in DNA by modified dNTP analogs can be ensured through enzyme-directed incorporation. As an alternative, post- incorporation modification through chemical coupling (e.g. using amino group-modified dNTPs) would be an option, but this approach cannot guarantee base specificity and complete modification of every position due to comparatively lower reaction efficiencies (12,13). The incorporation of dNTPs carrying different functional groups into DNA can be achieved through nick translation, random priming, primer extension, reverse transcription and PCR (14–17). Generally, an inverse relationship exists between product yield and the level of modified dNTP incorporation for various dNTP analogs tested (14,18). Amongst the various DNA modification protocols, the highest yield of fluorescent labeled DNA is obtained when natural DNA is used as the template, such as in nick translation, random priming and primer extension (14,15).

The complete enzyme-mediated fluorescent replacement of every base in a DNA molecule has not been achieved to date due to a number of limitations. Partial replacements of one dNTP (mainly dUTP or dCTP derivatives) at a time in the presence of the other natural dNTPs have been reported (14,15,18–20). It seems that incorporation of fluorophore-tagged dNTPs and thereafter the extension of the newly formed, label-carrying 3′-DNA termini are discriminated by most DNA polymerases (DNA pols) (21–23). This has been attributed to the hydrophobic nature or bulkiness of the fluorescent dye groups, as well as potential dye–dye or dye–enzyme interactions leading to early termination of DNA synthesis (14,15,17,18,24). Therefore, a number of difficulties remain to be solved in order to accomplish exclusive base-specific modification of DNA on every base position using, for example, fluorescent-labeled dNTP analogs. This will include establishing conditions that enable the DNA pol enzyme to bypass the linker/label moiety once the derivatives are incorporated, while maintaining the necessary minor groove– DNA interactions necessary for effective binding and moving along the DNA substrate (25,26). Thus, a screen of different DNA pols and labeled dNTP substrates is inevitable. Moreover, the physico-chemical nature of the attached fluorescent dyes or other modifying groups and their linker moieties also has to be taken into consideration. Consequently, the physical and chemical attributes of these dNTP-coupled modifying groups will also have an influence on the final DNA product (16,22). A detailed analysis of various modified dNTP analogs as potential substrates for nucleic acid modification such as high-density fluorescent DNA labeling using several assay systems will be presented. In particular, we tested the incorporation of 30 different modified dNTPs covering all four bases. We have found that the family B-type DNA pol, VentR exo–, is superior to the family A-type DNA pol, Taq, at incorporating most of these modified dNTP analogs. Moreover, we show that complete incorporation of all four modified dNTPs in the absence of naturally occurring dNTPs can be achieved.

Materials and methods

Enzymes

Restriction endonucleases, DNA-modifying enzymes and VentR exo– DNA pol were obtained from New England Biolabs. Taq DNA pol was purchased from Roche Diagnostics.

Deoxyribonucleoside 5′-triphosphates

Natural dNTPs were purchased from Roche Diagnostics. Synthesis and purification of the various reporter group-conjugated dNTP derivatives are described separately (Giller et al., accompanying manuscript). MR121-dUTP was a gift from Klaus Mühlegger (Roche Diagnostics).

DNA templates

Oligodeoxyribonucleotide primers and various model templates were of standard HPLC purification grade purchased from Thermohybaid and, whenever necessary, purified further by preparative PAGE (17). In order to study the principal acceptance of the various modified dNTPs and incorporation into DNA by different DNA pols, elongation of primers with a digoxigenin or biotin conjugated to their 5′ ends was monitored with the following template assay systems.

The homopolymer DNA template assays. The incorporation of each modified dNTP into DNA at up to 18 adjacent positions can be documented. The four model DNA templates have a common primer-binding site (underlined) followed by a stretch of 18 identical nucleotides (Fig. 1A). Each of the four modified nucleobases can be tested in this system for efficient incorporation. Due to difficulties encountered with the poly(G) homopolymer template, the incorporation of dCTP derivatives was also analyzed on an alternative DNA template with short and interrupted G stretches. This template assay system is similar to previously described stop and go template systems (17,21).

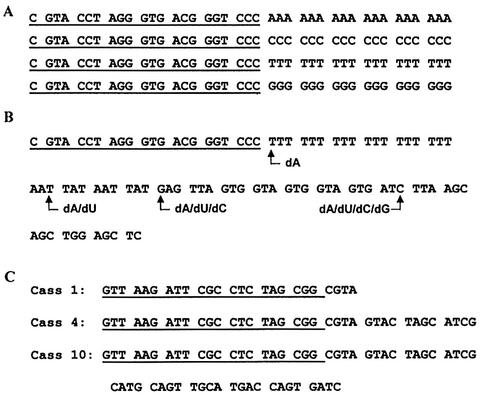

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the model DNA template systems used to evaluate dNTP derivatives. (A) The homopolymer DNA model templates. (B) The ‘stop and go’ template (Nuc T88), where dA is incorporated in the first 18 positions, followed by dA/dT (dU) in the next 14 positions, dA/dT/dC into the next 20 positions and finally dA/dT/dC/dG in the last 12 positions. (C) The cassette system DNA templates. Only templates 1, 4 and 10 are shown. For all cases, the primer-binding site is underlined.

The ‘stop and go’ (Nuc T88) and cassette template assays. In these two systems, the incorporation of a given modified dNTP derivative alone or in combination with other modified dNTP derivatives can be followed. These two template systems direct DNA synthesis of differing complexity, thereby providing different degrees of challenges to the DNA pol enzyme. In the ‘stop and go’ (Nuc T88) template, the incorporation of all the four nucleobases can be followed in short stretches in the order A, AT, ATC and finally ATCG over a 71 base stretch of DNA (Fig. 1B). Details of this assay have also been outlined previously (27). Alternatively, various shorter stop and go model templates designed for analysis of multiple modified dNTP within a 12 base stretch were also used for evaluation (17). Each of the templates has a common primer-binding site and varying numbers of four nucleotide sequences ranging from 1 to 10 blocks (17,21). Each building block, i.e. the cassette, is equivalent to four nucleobases (G, A, T and C) (Fig. 1C).

The natural DNA template assay. To follow the incorporation of modified nucleotide derivatives into natural DNA, we selected a pUC19 plasmid-based (nucleotides 448–750) template primer system. Either linearized pUC19 plasmid (HindIII digested) or a 300 bp PCR product generated from pUC19 were used as templates in both primer extension and PCR-based assays. The primers used for generating the 300 bp fragment were 5′-AGCTTGGCGTAATCATGGTCATAG and Bio/Dig-5′-AGCTGATACCGCTCGCCGCAGCC. The latter primer was also used for the labeling reaction to enable identification and analysis of newly synthesized DNA products by detecting the attached biotin or digoxigenin reporter groups.

Incorporation of modified nucleotides by primer extension

The acceptance of the various modified dNTPs by DNA pols was investigated by using either Taq or VentR exo– DNA pol through primer extension analysis or monitoring the appearance of a PCR product. Model template-based substrates were prepared by annealing equimolar amounts of template and primer as follows: 96°C for 2 min and 50°C for 10 min. Primer extension reactions were performed in a total volume of 10 µl containing 10 pmol of DNA substrate, 5–50 µM natural or modified dNTPs and 0.5–1 U of DNA pol. The unit (U) definitions for both Taq and VentR exo– DNA pols were in accordance with the suppliers’ definition. The buffer conditions were: Taq (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 1.5 mM MgCl2), VentR exo– [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100]. The reactions were incubated for 30 min to 1 h at 72°C and terminated by adding 10 µl of stop solution [98% (v/v) formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.01% (w/v) bromophenol blue]. The unpurified DNA samples were denatured (99°C for 5 min) and 3 µl aliquots loaded onto a denaturing 7 M urea–12% (v/v) polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad sequencing gel). After separation, the primer extension products were transferred onto a nylon membrane (Hybond™-N+, Amersham Biosciences) by contact blotting and analyzed by detecting the digoxigenin label on the primers’ 5′ end by using anti-digoxigenin-AP Fab fragments according to the standard protocol outlined by the supplier (Roche Diagnostics). To analyze incorporation into natural DNA, primer extension reactions were performed using the pUC19-based DNA templates. The reactions were done in a total volume of 50 µl containing 1 pmol of DNA template (HindIII-linearized pUC19 plasmid DNA or a 300 bp pUC19 derived PCR product) and 20 µM of a biotin-conjugated primer (see above). Each reaction contained 2 U of VentR exo– pol and 0.1 mM of each of the four dNTPs. The total 0.1 mM final concentration for each dNTP corresponds to either a natural or modified dNTP analog or a mixture at varying proportions of the two forms of the dNTPs as indicated in the figure legend. For all reactions, an annealing step (5 min at 96°C, followed by 2 min at 60°C) was followed by 1 h of primer extension at 72°C. After the reaction, a 5 µl aliquot of the unpurified reaction was mixed with 5 µl of stop solution. After denaturation, primer extension products were separated on a 7 M urea–6% (v/v) polyacrylamide gel. The products were visualized after biotin detection with a streptavidin–AP conjugate according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Roche Diagnostics). Occasionally, the labeling reactions were carried out with 5′-32P-labeled primers. In that case, the reaction products were detected directly (no blotting and antibody/streptavidin–AP reaction) by exposure to X-ray-sensitive films. This was done in order to demonstrate consistency of the results obtained with the indirect detection methods described above.

Incorporation of modified nucleotides by PCR

As a second method for measuring the effectiveness of modified dNTP incorporation, PCR was chosen. In PCR, in contrast to the primer extension reactions, the derivative nucleotides (after a few rounds of amplification) are also present in the template strand, so that in the end both strands consist at least partially of derivative compounds, with the exception of the unlabeled primer moieties at each 5′ end of duplex DNA. In the reaction mixtures, the respective natural nucleotides were replaced in a stepwise manner (20, 40, 60, 80 and 100%) by their modified analogs until they were completely substituted. In all PCRs, 2 U of DNA pol (Taq or VentR exo–) were used. For each reaction, 30–100 fmol of DNA template (linearized pUC19 plasmid or a 300 bp PCR product), 0.4 µM of each primer and 0.2 mM of each dNTP were used. The incubation step consisted of a 2 min denaturation at 95°C, followed by 30× (95°C, 30 s; 60°C, 30 s and then 5–10 min at 72°C). Unincorporated dye–triphosphates migrate as multiple bands between 0.2 and 2.5 kb in native agarose gels. When fluorescent nucleotide derivatives (excitable by UV light) were incorporated, the non-incorporated dye-labeled dNTPs had to be removed by purification on Nucleospin Extract columns (Macherey-Nagel) prior to gel analysis. Reaction products were resolved on a horizontal 2% (w/v) agarose gel and first directly examined under UV light before ethidium bromide staining. The expected but shifted product band was the indicator for good acceptance of a given derivative.

RESULTS

Assay systems to evaluate the modified dNTP substrates

Three model templates and one natural DNA template-based assay systems were used to evaluate the several modified dNTP derivatives. First, each modified dNTP analog was evaluated using the homopolymer template assay system (see Fig. 1A). In this assay, the incorporation of a modified dNTP can be monitored at up to 18 adjacent positions. Exceptions were dCTP derivatives. These could not always be incorporated up to 18 positions, probably as a result of poly(G)-template associated unusual structures such as G-quadruplexes (28). As an alternative, a 12 base long ‘stop and go’ template with two short poly(G) regions (5×G) that are interrupted by another nucleotide such as C or A was used additionally to evaluate the modified dCTP derivatives (17). The best incorporated modified dNTPs as identified in this first assay system were evaluated further for incorporation into a natural DNA sequence using the pUC19 plasmid-derived template assay. In this assay, a regular dNTP was replaced stepwise (in increments of 20%) by a corresponding modified derivative from 20 to 100%, respectively. To analyze modified dNTP derivative combinations, two defined model template assays were used, which differed in sequence complexity. The ‘stop and go’ (Nuc T88) template was designed in such a way that it instructed the incorporation of dA in the first 18 positions, followed by dA/dT in the next 14 positions, dA/dT/dC in the next 20 positions and finally dA/dT/dC/dG in the last 12 positions (see Fig. 1B). In the cassette template assay, individual building units for these model templates have been designated a cassette (Cass) consisting of the four natural bases (dG/dA/dT/dC). Therefore, for each given cassette template, the template number defines the number of cassette sequences encoded by that template, e.g. Cass 1 had one cassette, i.e. four bases (CGTA), while Cass 10 contained 10 cassettes, i.e. 40 bases (see Fig. 1C for examples). The modified dNTP combinations identified and confirmed with these two model template assay systems were then tested further in the natural DNA template assay with a pUC19-derived template (see Materials and Methods).

Evaluation of modified dNTP substrates

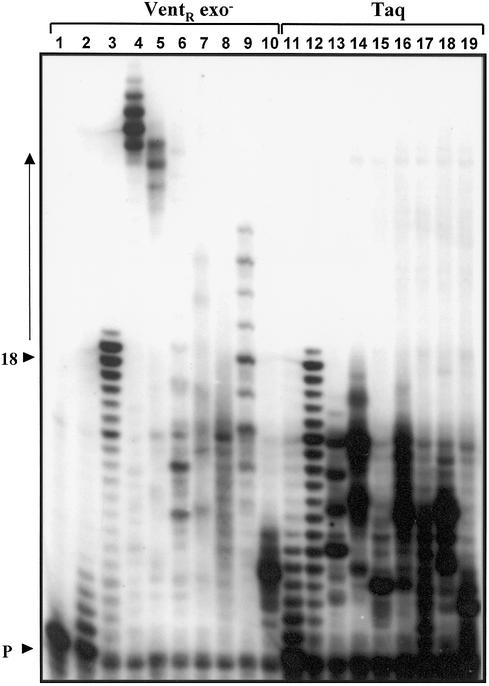

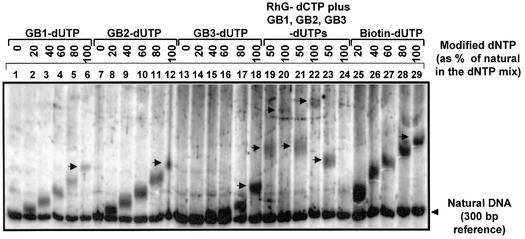

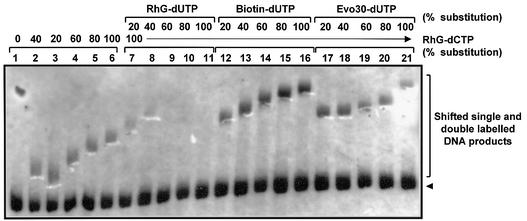

First, the substrate properties of each modified dNTP derivative were evaluated by using VentR exo– and Taq DNA pol in the homopolymer and natural (pUC19) DNA template assay systems. The DNA synthesis products were then evaluated by gel-based product analysis. Figure 2 shows a representative picture for the evaluation of several dUTP derivatives using the homopolymer template system. As parameters to select good modified dNTP derivatives, both the incorporation efficiency (yield) and the final length of the DNA products were considered. Yields were estimated by eye, taking into consideration different band intensities on the same gel blot. In most cases, each individual incorporation step was clearly documented. However, there were some derivatives that gave rise to poorly resolved incorporation products migrating as smears, e.g. MR121-dUTP and rhodamine green (RhG)-dATP conjugates (Table 1). The incorporation of some modified dNTP derivatives led to retardation in electrophoretic mobility and, consequently, shifted product bands, e.g. the incorporation of biotin- and RhG-dUTP conjugates (Fig. 2, lanes 4 and 5). However, with some dNTP derivatives, there were minor or no observable influences on the physico-chemical properties of the product DNA. There were a number of fluorophore-tagged dNTP derivatives which turned out to be poor substrates for both VentR exo– and Taq DNA pol. These led to early DNA chain terminations after only a few incorporations, e.g. Alexa 488-dUTP (Fig. 2, lane 10), Dy635-dUTP and Dy630-dATP (Table 1). In all cases, the incorporation by both VentR exo– and Taq DNA pol were compared simultaneously. We found that when equal amounts of enzyme activity were compared, VentR exo– displayed a superior incorporation performance compared with Taq in most cases (Fig. 2 and Table 1). This prompted us to focus most of our further work on evaluation of modified dNTPs on VentR exo– DNA pol. Occasionally, the final products were a few bases longer than the original model template (Table 1 and Fig. 5), probably as a result of DNA template slippage or terminal deoxyribonucleotidyltransferase activity by the DNA pols (29,30). The homopolymeric template assay system demands high-density incorporation of a given dNTP derivative since the same nucleotide must be incorporated at all adjacent 18 positions. Such complex sequences are rarely found in nature but provided a challenging preliminary screening step to identify best performing candidate dNTP derivatives and DNA pols for high-density fluorescent DNA labeling. Therefore, as a next step, the best incorporated candidate dNTP derivatives were tested for incorporation into natural DNA sequence using the pUC19 plasmid template assay system. We used VentR exo– DNA pol in PCR- (linear and asymmetric) and primer extension-based assays to evaluate the dNTP derivatives. Initially, the replacement of only one dNTP at a time was monitored. A given natural dNTP was substituted gradually (in steps of 20%) with its modified counterpart in the DNA synthesis reaction. The DNA synthesis products were identified after agarose (native) or polyacrylamide (denaturing) gel separation by detection of the biotin or digoxigenin reporter groups on the elongated primers. An example is shown in Figure 3. The incorporation of several modified dNTPs derivatives was analyzed using the natural 300 bp DNA sequence as a template. The primer extension products obtained from stepwise substitution (20–100%) of natural dTTP by Gnothis Blue 1 (GB1)-dUTP (lanes 2–6), GB2-dUTP (lanes 8–12) and GB3-dUTP (lanes 14–18) are shown. The natural DNA product baseline expected when only natural dNTPs were used for DNA synthesis is indicated (lanes 1, 7 and 13). Meanwhile, in lanes 25–29, dTTP was replaced stepwise by biotin-dUTP (20–100%). In most of these reactions, an upward shifted product band (relative to the previous reaction) is detected. However, for GB3-dUTP, a detectable shifted product is only observed after 40% substitution. Moreover, even at 100% substitution, the GB3-dUTP-induced shift is less than that obtained with similar substitutions of GB1-dUTP and GB2-dUTP. This is attributed to the presence of one more negative charge in the GB3 dye compared with GB1 and GB2, respectively (for structures see Giller et al., accompanying manuscript). This reflects the influence of the net charge on the dye coupled to the dNTP on the electrophoretic migration of the final DNA product. In lanes 19–24, RhG-dCTP was also added as the second modified dNTP in the DNA synthesis reaction in addition to GB1-dUTP, GB2-dUTP or GB3-dUTP (from left to right), respectively. The degree of substitution for the two derivatives was at 50 and 100%, respectively. In all cases when both nucleotides were at 50% substitution, a product was obtained (see arrows in lanes 19, 21 and 23). At 100% substitution of RhG-dCTP and GB1-dUTP or GB2-dUTP (lanes 20 and 22), diffuse bands that were shifted further relative to the products in the previous reactions were seen. However, at 100% substitution of RhG-dCTP and GB3-dUTP (lane 24), no products were detected. The substituted DNA products containing the modified dUTP derivatives shifted higher as the level of substitution with each dNTP derivative was increased. Additionally, these products did not form a sharp band and appeared diffuse (Fig. 3). Moreover, the DNA product yield seemed to decrease with increasing levels of substitution. This could not be determined for the biotin-dUTP products because the higher label density also led to a stronger signal upon reaction of the samples with streptavidin–AP conjugates.

Figure 2.

Substrate properties of modified dNTP derivatives in primer extension assays. The incorporation of each modified dNTP derivative was evaluated in the homopolymer template assay. A 10 pmol concentration of the DNA substrate (homopolymer template annealed to a 5′ digoxigenin- labeled primer), 1 U of DNA pol (VentR exo– or wild-type Taq) and 50 µM of each dNTP derivative to be tested were incubated in a DNA pol assay as outlined in Materials and Methods. The primer extension products were resolved on a 7 M urea–12% (v/v) polyacrylamide gel and identified after detection of the 5′ digoxigenin label on the primer. (A) Evaluation of dUTP derivatives. Lanes 1–10, VentR exo– DNA pol; lanes 11–19, Taq DNA pol. Lane 1, primer alone (negative control); lanes 2 and 11, dTTP (5 µM); lanes 3 and 12, dTTP (50 µM) (positive control); lanes 4 and 13, biotin-dUTP; lanes 5 and 14, RhG-dUTP; lanes 6 and 15, Atto655-dUTP; lanes 7 and 16, GB1-dUTP; lanes 8 and 17, GB3-dUTP; lanes 9 and 18, Evo30-dUTP; and lanes 10 and 19, Alexa 488-dUTP. Arrowheads indicate the positions of the unextended primer as well as the primer elongated by 18 dTs. The arrow indicates the shift in product size due to the incorporation of labeled nucleotides.

Table 1. Summary of the incorporation of VentR exo- and Taq with various modified dNTPsa.

| Reporter groupb | dUTP VentR exo– | Taq | dATP VentR exo– | Taq | dCTP VentR exo– | Taq | dGTP VentR exo– | Taq |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | 18 | 18 | >18 | 18 | 17 | 19 | 19 | 19 |

| Biotin | >18 | 7 | >18 | 6 | 8 | 3 | >18 | 8 |

| RhG | 14 | 6 | 8, plus smear | 5 | 8, plus smear | 4 | 17–18 | 5 |

| Oregon Green | 9, plus smear | 2 | n.a.c | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Alexa 488 | 5 | 3 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Cy5 | 10–11 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | n.a. | n.a. |

| Evo30 | 14 | 5 | 13, plus smear | 6 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 4 |

| Evo90 | 10–11 | 5 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Atto655 | 14 | 6 | 16 | 16 | 5 | 1 | n.a. | n.a. |

| MR121 | 5, plus smear | 5, plus smear | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Dy635 | 2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Dy630 | n.a. | n.a. | 4 | 2 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| GB1 | 11 | 4 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| GB2 | 13 | 13 | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| GB3 | 13 | 13 | 13, plus smear | 13 | 5 | n.a. | 13 | 13 |

aIncorporation for each dNTP derivative from the homopolymer template primer extension assay was determined as outlined in Materials and Methods. The total number of incorporations out of 18 is indicated. In some cases, however, depending on the modified dNTP derivative, incorporation can only be observed to a certain limit and thereafter the DNA chains cannot be resolved any more, leading to slow migrating smears of undefined length.

bRhG, rhodamine green; Cy5, cyanine 5; Evo30, Evoblue 30; Evo90, Evoblue 90; GB1, Gnothis Blue 1; GB2, Gnothis Blue 2; GB3, Gnothis Blue 3.

cn.a., not available.

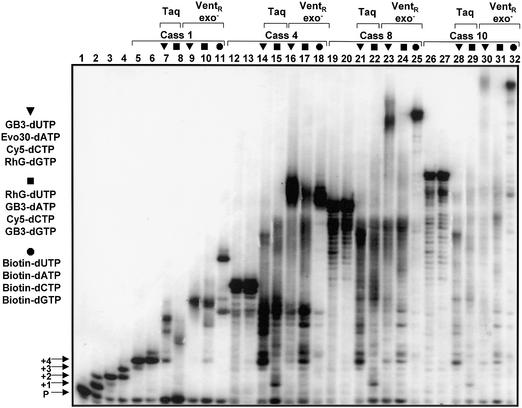

Figure 5.

Complete substitution of natural dNTPs by modified dNTPs. A 10 pmol concentration of each of the cassette model DNA templates 1, 4, 8 and 10 (a single cassette is equivalent to four bases, i.e. CGTA; see Fig. 1), 50 µM each of the four dNTPs and 1 U of either VentR exo– or Taq DNA pol were incubated in a primer extension assay as outlined in Materials and Methods. In these reactions, the primer carries a 5′ digoxigenin label. After the reactions, the products were separated on a 7 M urea–12% (v/v) polyacrylamide gel, transferred onto nylon membranes and primer extension products identified after digoxigenin detection. The dNTP mixture used for each reaction consists of exclusively natural, or biotin or fluorescent dNTPs, respectively. The primer alone is denoted with P, and the one (+1), two (+2), three (+3) and four (+4) dNTP incorporations are also indicated (lanes 1–4). They contained one (dATP), two (dATP/dCTP), three (dATP/dCTP/dGTP) and four (dATP/dCTP/dGTP/dTTP) natural dNTPs, respectively. The rest of the reactions contained all four dNTPs, either natural or modified. Lanes 5–11, cassette model DNA template 1; lanes 12–18, cassette model DNA template 4; lanes 19–25, cassette model DNA template 8; lanes 26–32, cassette model DNA template 10. Lanes 5, 7, 8, 12, 14, 15, 19, 21, 22, 26, 28 and 29, Taq DNA pol; lanes 6, 9–11, 13, 16–18, 20, 23–25, 27 and 30–32, VentR exo– DNA pol. Natural dNTPs were used in lanes 5, 6, 12, 13, 19, 20, 26 and 27. The DNA products synthesized exclusively using the four biotin-dNTP derivatives are denoted with a black circle above each lane. The two sets of reactions containing exclusively fluoroscent dNTP derivatives replacing each of the natural dNTPs are denoted by a black triangle (GB3-dUTP; Evo30-dATP; Cy5-dCTP; RhG-dGTP) and a black square (RhG-dUTP; GB3-dATP; Cy5-dCTP; GB3-dGTP) above the respective lanes. Full-length products were obtained for every template with VentR exo– DNA pol and the combination of GB3-dUTP; Evo30-dATP; Cy5-dCTP and RhG-dGTP (triangle), but not with Taq DNA pol or the combination of RhG-dUTP; GB3-dATP; Cy5-dCTP; GB3-dGTP (square).

Figure 3.

Incorporation of modified dNTPs into natural DNA. A 1 pmol concentration of a natural DNA substrate (5′ biotin-labeled 300 bp PCR product annealed to a 5′ biotin-labeled primer), 2 U of DNA pol (VentR exo–) and 0.2 mM of each of the four dNTPs were used to test modified dNTP derivatives in the primer extension assay as outlined in Materials and Methods. One of the four natural dNTPs was gradually (in steps of 20%) substituted by its modified derivative until it was completely (100%) replaced. After the reaction, the products were separated on a 7 M urea–6% (v/v) polyacrylamide gel followed by transfer onto a nylon membrane and the DNA visualized after detecting for the 5′ biotin label, which is on both the natural DNA template and the extended primer. The levels of replacement of a given natural dNTP by its modified derivative in the dNTP mixture are indicated as a percentage. The level of the 300 bp natural DNA template delineates the baseline position with natural dNTP exclusively (indicated by an arrowhead). Lanes 1–6, GB1-dUTP; lanes 7–12, GB2-dUTP; lanes 13–18, GB3-dUTP; lanes 25–29, biotin-dUTP. In lanes 19–24, double dNTP substitutions at 50 and 100% are shown. Lanes 19 and 20, RhG-dCTP and GB1-dUTP; lanes 21 and 22, RhG-dCTP and GB2-dUTP; lanes 23 and 24, RhG-dCTP and GB3-dUTP. For each modified dNTP derivative, gradual substitution leads to a corresponding shift of modified product DNA. Arrows indicate the final product of the 100% substitutions (lanes 6, 12, 18 and 29) and the 50% as well as the 100% substitutions of the double dNTP substitutions (lanes 19–24).

Testing incorporation of modified dNTP derivatives in combinations

The analytical procedures described so far focused mainly on the incorporation of single modified dNTP derivatives. The overall goal would be to simultaneously introduce more than one distinguishable modified dNTP into a DNA molecule or, alternatively, to modify every base position. Encouraged by the results in the previous section, we next evaluated the incorporation of different fluorescently modified dNTP combinations. In this case, the complete replacement of more than one of the four natural dNTPs at a time with the corresponding modified dNTP analogs (preferably fluoro-dNTPs) was investigated. The ‘stop and go’, cassette or natural DNA template assays were used systematically to test various two and three modified dNTP analog combinations. A selection of results from the several modified dNTP combinations evaluated are summarized in Table 2. The data presented show that some fluoro-dNTP combinations are compatible for DNA synthesis, giving rise to expected full-length DNA products when incorporated together into the same DNA chain. For example, RhG-dCTP/GB1-dUTP, Atto655-dCTP/GB2-dUTP and GB3-dCTP/Evoblue 30 (Evo30)-dUTP combinations were all compatible for DNA synthesis in model template assays. Meanwhile, some modified dNTP combinations were not compatible for DNA synthesis when incorporated together in the same DNA chain. Hence these combinations failed to give the expected full-length DNA products when present at 100% substitution of the corresponding natural dNTPs. For example, 100% substitution of RhG-dCTP, RhG-dUTP and Evo30-dUTP alone gave the expected products when incorporated opposite model or natural DNA templates. However, in pairwise combinations, only the RhG-dCTP/Evo30-dUTP combination at 100% substitution yielded the expected full-length DNA synthesis products (Table 2). An example of modified dNTP combination incorporation into natural DNA sequence is shown in Figure 4. In this experiment, dCTP was first substituted with RhG-dCTP stepwise from 20 to 100% (lanes 2–6; note that the reactions with 20 and 40% substitution were loaded in the inverse order). The modified DNA product bands were identified through decreased electrophoretic mobility proportional to the degree of substitution. Additionally, the incorporated RhG-dCTP fluorescence was visualized by eye upon examination of the gel blots under UV after transfer of the modified nucleic acids onto the nylon membrane. These were marked with a dash at the lower edge (seen as white dashes below the corresponding biotin detection signal in the picture). As the second modified dNTP, dTTP was then substituted similarly by RhG-dUTP (lanes 7–11), biotin-dUTP (lanes 12–16) or Evo30-dUTP (lanes 17–21), while RhG-dCTP was maintained constant at 100%. Under these conditions, clearly shifted product bands were only obtained with the biotin-dUTP and the Evo30-dUTP. However, when RhG-dUTP was included, products only up to 40% substitution were detectable. On the other hand, as already mentioned, RhG-dUTP or RhG-dCTP alone can give products at 100% substitution (Table 2 and data not shown). A remarkable feature of the Evo30-dUTP incorporation is the uneven slope of the shifted product, which is rather low up to 60% substitution. However, at 80 and 100% substitution, the product shifted to a level almost similar to that obtained with biotin-dUTP. This indicates reduced preference for the modified substrates by the VentR exo– DNA pol compared with the natural dNTP substrates. As the relative concentration between the two dNTPs (dTTP/RhG-dUTP) increases, this discrimination by VentR exo– DNA pol is overcome. To confirm that target length was synthesized with the natural DNA templates, the shifted modified DNA product bands in Figure 4 were excised from the gel and eluted. The recovered DNA was serially diluted and these diluted samples used as templates in PCR with regular dNTPs. A reverted PCR product of the expected size (300 bp) was obtained, confirming that target length synthesis had been achieved and that the modified DNA can be used as template (data not shown). As a negative control, an eluate of a gel piece excised from an adjacent position on the same gel was used. There was also a tendency for the modified DNA products to precipitate when cooled or frozen overnight (Table 2). This was observed upon incorporation into the long natural DNA template assay but not with the short model templates. Generally, the tendency to precipitate increased with high degrees of substitution (80–100%) and was noticed more with the hydrophobic dyes.

Table 2. Evaluation of DNA synthesis efficiency of different modified dNTP combinations by VentR exo– DNA polymerase.

| Nucleotide combinationa dUTP | Productb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| dATP | dCTP | dGTP | ||

| GB3c | RhG | Yesd | ||

| GB1 | RhG | Yes | ||

| GB2 | Atto655 | Yes | ||

| Evo30 | GB3 | Yes | ||

| RhG | RhG | No (50%) | ||

| RhG | Evo30 | Yesd | ||

| RhG | RhG | No (80%) | ||

| Evo30 | Atto655 | Yes | ||

| Atto655 | Evo30 | Yes | ||

| RhG | Cy5 | No (60%) | ||

| Cy5 | RhG | No (80%) | ||

| RhG | RhG | Evo30 | Yesd (but poor yield) | |

| GB3 | RhG | GB3 | No | |

| GB3 | GB3 | RhG | Yes4 | |

| GB3 | Biotin | RhG | GB3 | Yes |

| GB1 | GB3 | RhG | RhG | Yesd (but very poor yield) |

| Biotin | Biotin | Biotin | Biotin | Yesd |

aCombinations were tested in DNA incorporation assays using the cassette or Nuc T88 model templates first as outlined. All the four nucleotides were present in these assays, but only the modified dNTP (at 100%) composition is indicated, and those dNTPs which are not indicated here were, therefore, natural.

bYes: modified DNA products observed with modified dNTP combination until 100% substitution of the corresponding natural dNTPs. No: no modified DNA product was observed above the degree of substitution indicated in parentheses.

cDye abbreviations are as used in Table 1.

dModified DNA products from this combination precipitated after overnight storage at –20°C.

Figure 4.

Incorporation of modified dNTPs into natural DNA. The experimental conditions were as outlined in Figure 3. Lane 1, natural dNTPs only; lanes 2–6, stepwise replacement of dCTP using RhG-dCTP with increments of 20% until complete replacement (100%). Note that the loading of 20 and 40% replacement reactions is reversed in lanes 2 and 3. Lanes 7–21, RhG-dCTP replacement was kept at 100%, followed by stepwise replacement of dUTP with RhG-dUTP (lanes 7–11), biotin-dUTP (lanes 12–16) and Evo30-dUTP (lanes 17–21), respectively. The arrowhead indicates the position of the 300 bp natural DNA template.

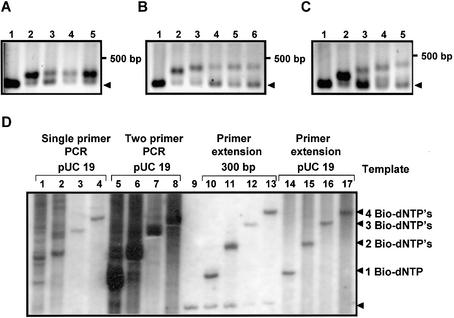

Total substitution of all natural dNTPs by modified analogs in DNA

After the systematic testing of various modified dNTP combinations, we eventually identified some combinations of four modified dNTPs that could be used to synthesize modified DNA in the absence of natural dNTPs. We used the cassette model template assay system to show DNA synthesis using either exclusively fluorophore- or biotin-labeled dNTP derivatives. Four cassette templates (Cass 1, 4, 8 and 10) were used as templates. The system was calibrated using the natural dNTPs as shown in Figure 5, lanes 2–6, 12 and 13, 19 and 20, and 26 and 27, respectively. As expected, full-length DNA products were synthesized using the natural dNTPs with both Taq and VentR exo– DNA pol, represented by the two lanes of expected full-length product obtained with Cass 1, 4, 8 and 10 templates. Two sets of four fluoro-dNTP combinations were tested for DNA synthesis (indicated in Fig. 5). In all cases, some modified DNA products arising from primer extension were detected. However, mostly short early synthesis termination products were accumulated. However, using the GB3-dUTP, Evo30-dATP, Cy5-dCTP and RhG-dGTP combinations, some expected full-length modified DNA products were synthesized by VentR exo– (lanes 9, 16, 23 and 30). Additionally, modified DNA synthesized exclusively from biotin-dNTP derivatives using VentR exo– DNA pol is shown (lanes 11, 18, 25 and 32). This result demonstrated that complete substitution of all natural dNTPs by fluorophore- or biotin-tagged dNTP analogs in DNA synthesis was possible using VentR exo– DNA pol. It also confirmed that, in principle, it was possible to label every base position in a DNA chain and achieve up to 40-base-long products using the cassette model templates. The overall modified DNA product yield was lower compared with the natural DNA synthesis reactions, and even with such short chains the resulting modified DNA products already displayed a tendency to form smears. In a second approach, we tested the incorporation of biotin-dNTPs in a primer extension assay using the 300 bp PCR product as template. All four nucleotides were substituted simultaneously at 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100% (0.2 mM final concentration of each nucleobase). Finally, the four nucleotides were substituted one after another at 100%. A product band could be detected with each of the biotin-modified nucleobases (Fig. 6A, lanes 2–5), which was shifted relative to the unmodified 300 bp control (indicated by an arrowhead and in lane 1 of each panel). The shift for each of the four nucleotides was almost the same. However, when four nucleotides were replaced simultaneously, the shift increased relative to the degree of substitution up to 60% (Fig. 6B, lanes 2–6). Above that level, the modified DNA migrated in the same position, indicating the obvious limit of resolution of the gel. Substitution with biotin-dNTPs in the order dATP, dATP/dCTP, dATP/dCTP/dGTP and finally all four (Fig. 6C, lanes 2–5) resulted in a steady shift of the product band whose intensity decreased with increasing degree of substitution. This approach clearly showed a full substitution of all four natural dNTPs by biotin-modified nucleotides in a natural DNA sequence. The band still migrating in the natural 300 bp position represents unconsumed 300 bp template DNA as well as the complementary single strand displaced from the original double strand of the natural DNA template. To show the use of these biotin-modified dNTPs in PCR, the HindIII-digested pUC19 plasmid and the 300 bp PCR product were used as templates. The cycling reactions were performed with one or two primers, while for primer extension reactions the forward primer was used. In Figure 6D, dATP (lanes 1–4), dATP/dCTP (lanes 5–8), dATP/dCTP/dGTP (lanes 10–13) and all four nucleotides (lanes 14–17), respectively, were substituted by their biotin analogs. Lane 9 shows the internal standard for calibration, where the natural 300 bp PCR DNA product runs. This was used as a template in lanes 10–13, while in lanes 1–4 linearized pUC19 plasmid provided the template. With increasing degree of substitution, the desired products were shifted relative to each other, demonstrating successful incorporation of the modified dNTPs. However, if just one or two nucleotides were replaced, there seemed to be more unspecific products synthesized compared with the reactions where three or four biotin derivatives were present (compare lanes 1–4). At the moment, the lack of stringency when one and two nucleotides were substituted is not fully understood. This observation is also true for the reactions in lanes 5–8 where two primers were present in the cycling reactions. There were a lot of unspecific products, visible as a smear below and above the expected bands, most probably indicating unspecific priming. The clearest picture was obtained from the simple primer extension reactions (lanes 9–17). When only natural dNTPs were present in the reactions, no other product was evident. In lanes 10–13, shifted bands were obtained with increasing retardation as more natural dNTPs were replaced. The same was true principally for reactions containing linearized pUC19 plasmid as a template (lanes 14–17). However, in addition to the expected shifted bands, diffuse high molecular weight smears were also obtained. It may be a result of incompletely digested pUC19 in the original template or unspecific priming. In summary, the various tests performed indicate that net DNA synthesis occurs at a reasonable degree in most cases, even though the results from the various assays performed did not always lead to the expected products. The main question of exactly how long products can a DNA pol synthesize remains to be determined in future experiments. It seems that the limit is not in the DNA pol itself, but rather the resolution of the gel system used in our studies.

Figure 6.

Complete substitution of all four natural dNTPs by biotinylated derivatives. The DNA pol reactions were performed as outlined in Materials and Methods. In (A)–(C), 1 pmol of natural DNA substrate (5′ biotin-labeled 300 bp pUC19 PCR product), 2.5 U of VentR exo– DNA pol and 0.2 mM of each of the four dNTPs were used in a primer extension assay. After the reaction, the DNA synthesis products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel followed by ethidium bromide staining. (A) A single natural dNTP at a time was replaced by the corresponding biotin-dNTP derivative. Lane 1, control reaction with only natural dNTPs; lane 2, dATP replaced by biotin-dATP; lane 3, dCTP replaced by biotin-dCTP; lane 4, dGTP replaced by biotin-dGTP; lane 5, dUTP replaced by biotin-dUTP. (B) Stepwise replacement of all four dNTPs simultaneously by the corresponding biotin-dNTPs. Lane 1, control reaction with natural dNTPs; lanes 2–6, substitution levels of 20, 40, 60, 80 and 100%, respectively. (C) Complete replacement of one natural dNTP after another until all the four natural dNTPs were replaced by the corresponding biotin-dNTPs. Lane 1, control reaction with natural dNTPs; lane 2, dATP replaced by biotin-dATP; lane 3, dATP and dCTP replaced by biotin-dATP and biotin-dCTP; lane 4, dATP, dCTP and dGTP replaced by biotin-dATP, biotin-dCTP and biotin-dGTP; lane 5, all natural dNTPs replaced by biotin-dATP, biotin-dCTP, biotin-dGTP and biotin-dUTP. Note that the 100% substituted final 300 bp products are present in (C) lane 5 and (B) lane 6, and they migrate at the same position. (D) Experiments were carried out as described in (A) using linearized pUC19 DNA (lanes 1–8 and 14–17) or the 300 bp pUC19 PCR product (lanes 9–13) as a template. To facilitate newly synthesized DNA identification, in all cases one of the primers used had a 5′ biotin label. For PCR amplification (with one or two primers), 0.1 pmol of HindIII-linearized pUC19 template was used to introduce the biotinylated dNTP derivatives (lanes 1–8). In the primer extension reactions, 1 pmol of 5′ biotin-labeled 300 bp pUC19 PCR product or linearized pUC19 DNA was used (lanes 9–17). Lane 9 represents a control reaction where only natural dNTPs are included. The order of substitution in all reaction blocks was: biotin-dATP (lanes 1, 5, 10 and 14), biotin-dATP and biotin-dCTP (lanes 2, 6, 11 and 15), biotin-dATP, biotin-dCTP and biotin-dGTP (lanes 3, 7, 12 and 16) and all four natural dNTPs replaced (lanes 4, 8, 13 and 17). Arrowheads indicate the position of the 300 bp natural DNA template.

DISCUSSION

DNA pol-directed incorporation of NTPs linked to detectable reporter groups (fluorophores, biotin or digoxigenin) or other functional chemical groups (COO–, NH2, SH, imidazole, etc.) provide an important experimental tool for nucleic acid modification. However, the generation of modified DNA probes is often compromised by poor incorporation of modified dNTP derivatives (e.g. fluoro-dNTPs) into DNA (19,31,32). Consequently, current fluorescent DNA labeling protocols have been limited mostly to partly substituting a single dNTP with its modified derivative, while the other three dNTPs are kept natural. Even with such approaches, inverse relationship between modified DNA product yield and the content of modified dNTP incorporation has been observed (14,15,20). The exact nature of the interactions that occur between DNA pol and modified dNTP substrates or growing modified DNA chains are not yet fully understood. Therefore, high-density DNA modification where two or three or all the natural dNTPs are replaced by their modified derivatives presents a major challenge. In this case, both enzymatic incorporation and the physico-chemical properties of the modified dNTP substrates must be optimized. Our investigation presented here had three primary objectives. First, a broad range of modified dNTP substrates were tested in different assay systems for incorporation into selected model and natural DNA sequences. The goal was to identify those modified dNTP derivatives with the best incorporation performance. Secondly, we compared the incorporation performance of a type A (Taq) and a type B (VentR exo–) DNA pol with the various modified dNTP substrates. Thermophilic DNA pols were preferred to enable application of thermal cycling protocols, which is an advantage when starting material for generating labeled probes is scarce. Additionally, synthesis at elevated temperatures might be helpful to overcome secondary structures in the DNA template, which may otherwise lead to synthesis stops. We also found that at higher temperature, the highly modified DNA product was more soluble and less prone to precipitation. Finally, using both fluoro-dNTPs and biotin dNTP analogs, we demonstrated that all four natural dNTPs could be completely replaced in DNA synthesis reactions.

The evaluation of several modified dNTP substrates using gel-based product analysis is summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2. The gel-based product analysis system used had a further advantage in that the incorporation efficiency could be determined in terms of product yield and target length synthesis, as well as early synthesis stops. The influence of various modification groups on the physico-chemical behavior of the resulting DNA chains could also be observed. Distinct differences in both incorporation threshold and the overall efficiency of various modified dNTP derivatives as substrates for Taq and VentR exo– pols were observed (Table 1 and Fig. 2). These variations seem to depend on the chemical nature of the attached group, the linker moiety used for the attachment to the dNTP and the nucleobase to which a particular modification group is attached. A number of reasons have been proposed to explain these variations in incorporation of different dNTP derivatives. The structure and size of the reporter/modification molecule as well as its solubility may all significantly influence incorporation. Steric hindrance as a result of bulkiness introduced onto the regular dNTP structures through modification is one major problem. However, from our experiments, we found that all the biotin-dNTP analogs were well incorporated in comparison with the various fluorescent dNTP analogs. Taking into consideration the size and structure of the biotin reporter group and its long linker, steric hindrance alone might not be the main reason for synthesis stops after incorporation. Molecular interactions (e.g. hydrophobic interactions) between the already incorporated modified dNTPs might also lead to DNA pol stalling or dissociation. Subsequently, the enzyme may fail to rebind the modified DNA ends after dissociation due to lack or obstruction of the regular recognition sites. Another possibility is that the high density of incorporated fluoro-dNTPs may form highly hydrophobic ‘quasi fluoro-dye polymers’ as the modified DNA chain grows. Such a potential formation of false fluorescent dye polymers could occur by ‘dye–dye’ interactions stabilizing the attachment of unincorporated dye-nucleotides. These may fold or aggregate in such a way that the DNA termini are inaccessible. Moreover, heteroduplex instability arising from hydrophobic interactions between the incorporated dyes may result in poorly annealed 3′ OH termini. In general, in the natural DNA template assay, we observed a tendency for the incorporation to decrease from pyrimidines to purines within the fluoro-dNTP derivatives group. We do not have an obvious explanation for these differences in incorporation behavior between purine and pyrimidine fluoro-dNTPs, but we speculate that differences in fluoro-dye attachment position in the pyrimidine and purine base heterocycles may have an influence (Giller et al., accompanying manuscript).

Alteration in the physico-chemical nature of the modified DNA products was characterized by smears upon loading onto the gel or precipitates after the DNA pol reaction when the reactions were left on ice or frozen overnight (data not shown). This may be attributed to the hydrophobic nature of the different groups conjugated to the dNTPs. Molecular interactions might occur between the incorporated reporter groups, or the DNA chains may associate with modification groups on unincorporated dNTPs, through, for example, intercalation resulting in formation of aggregates. Attempts to improve the resolution of such modified DNA products by including methanol (0–25%), ethanol (10–25%) or formamide (25%) in gels were not successful (data not shown). DNA precipitates could be redissolved by heating or mild alkaline pH (e.g. 1× TBE, pH 8.3). The addition of organic solvents such as ethanol, methanol or 2-isopropylalcohol, which are solvents for the monomeric fluorescent dyes, could not redissolve these precipitates. Therefore, the hybrid nature of the highly modified DNA chains seems to prevent proper redissolving. While natural DNA is water soluble and precipitates in organic solvents, the fluorophore dye part of modified DNA molecules displays the opposite behavior. Formamide, dimethylformamide and dimethylsulfoxide also had no influence on the redissolving process. The possibility that fluorescent-labeled DNA might interfere with downstream product analysis events, such as the efficiency of transfer from the gel to the nylon membranes or the chemiluminescent detection reaction, could be ruled out by reconfirming the results using 5′-32P-labeled primers in the primer extension assays instead of biotin-labeled primers (data not shown).

The influence of several additives was also tested, including betain (0.1–2 M), spermidine (0.125–25 mM), CHAPS [0.05–8% (v/v)] and the phase transfer catalyst tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulfate (0.1–80 mM). However, none of these additives enhanced incorporation of any of the dNTP analogs tested in terms of target length synthesis, intermediate products or product yield (data not shown).

In most cases tested, we found that VentR exo– DNA pol produced better incorporation of modified dNTP products compared with Taq DNA pol (see Fig. 2 and Table 1). However, there were some dNTP modifications where both enzymes showed similar incorporation performances (e.g. Atto655-dATP, GB3-dATP and Alexa 488-dUTP). Generally, all modified dNTPs were incorporated to a lesser extent compared with the natural dNTPs, in agreement with what others have reported (14,18,23). Therefore, in addition to good modified dNTP substrates, carefully designed mutagenesis to reduce steric hindrance or other molecular interactions between the DNA pol and the incoming modified dNTPs or those already incorporated in the growing DNA chain is essential to improve incorporation. Finally, we demonstrated the complete substitution of all four natural dNTPs in DNA through the simultaneous incorporation of four differently modified dNTP analogs after systematic testing of various modified dNTP combinations (Table 2). Certain fluoro-dNTPs were well incorporated when present alone in the DNA synthesis. However, they were poorly incorporated or failed to give DNA products at all when provided in combination with other fluoro-dNTPs. One explanation could be possible molecular interactions between certain fluoro-dNTPs when present together in a growing DNA chain. The DNA pol might also be involved in such interactions leading to abortive DNA synthesis. On the other hand, there are some fluoro-dNTPs compatible for DNA synthesis when incorporated in combination. An example is shown in Figure 5 using the cassette model sequence templates. In this case, using exclusively fluoro- or biotin-dNTP analogs, it was possible to synthesize a 40 bp long modified DNA fragment with VentR exo– DNA pol (lanes 30 and 32). This result shows that it was possible to modify every position in a DNA molecule using either fluorophore- or biotin-tagged dNTP derivatives. Working on the assumption that 10–12 dNTPs are equivalent to one helix turn, this result confirms that VentR exo– DNA pol is able to make at least three helix turns incorporating modified dNTP analogs into every position. As further proof of this principle, a 300 bp long modified DNA product was synthesized by VentR exo– using exclusively biotin-dNTPs. In conclusion, the work presented here provides a basis to prove that high-density modified DNA product with fluoro-dNTPs or other types of modified dNTPs can be generated through DNA pol-directed incorporation. However, further optimization of both the enzymatic incorporation and the physico-chemical properties of modified dNTP substrates will be necessary to ensure efficiency. Meanwhile, generation of such DNA probes may be useful in a wide range of applications. For example, the complete high-density fluorescent labeling of DNA is an absolute necessity for single molecule DNA sequencing or single molecule detection procedures requiring highly labeled DNA probes (10,11). Highly modified nucleic acid probes would also enhance the efficiency of in vitro selection and enrichment of different types of ligands in applications such as SELEX (8,9).

Acknowledgments

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Klaus Mühlegger and Professor Rudolf Rigler for many stimulating discussions, and Marie-Claire Sakthivel for her technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lichter P., Cremer,T., Borden,J., Manuelidis,L. and Ward,D.C. (1988) Delineation of individual human chromosomes in metaphase and interphase cells by in situ suppression hybridization using recombinant DNA libraries. Hum. Genet., 80, 224–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNeil J.A., Johnson,C.V., Carter,K.C., Singer,R.H. and Lawrence,J.B. (1991) Localizing DNA and RNA within nuclei and chromosomes by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genet. Anal. Tech. Appl., 8, 41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennline K.J., Pellerito-Bessette,F., Umland,S.P., Siegel,M.I. and Smith,S.R. (1992) Detection of in vivo-induced IL-1 mRNA in murine cells by flow cytometry (FC) and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH). Lymphokine Cytokine Res., 11, 65–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu H., Ernst,L., Wagner,M. and Waggoner,A. (1992) Sensitive detection of RNAs in single cells by flow cytometry. Nucleic Acids Res., 20, 83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen X. and Kwok,P.Y. (1997) Template-directed dye-terminator incorporation (TDI) assay: a homogeneous DNA diagnostic method based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 347–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith L.M., Sanders,J.Z., Kaiser,R.J., Hughes,P., Dodd,C., Connell,C.R., Heiner,C., Kent,S.B. and Hood,L.E. (1986) Fluorescence detection in automated DNA sequence analysis. Nature, 321, 674–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prober J.M., Trainor,G.L., Dam,R.J., Hobbs,F.W., Robertson,C.W., Zagursky,R.J., Cocuzza,A.J., Jensen,M.A. and Baumeister,K. (1987) A system for rapid DNA sequencing with fluorescent chain-terminating dideoxynucleotides. Science, 238, 336–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gourlain T., Sidorov,A., Mignet,N., Thorpe,S.J., Lee,S.E., Grasby,J.A. and Williams,D.M. (2001) Enhancing the catalytic repertoire of nucleic acids. II. Simultaneous incorporation of amino and imidazolyl functionalities by two modified triphosphates during PCR. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1898–1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee S.E., Sidorov,A., Gourlain,T., Mignet,N., Thorpe,S.J., Brazier,J.A., Dickman,M.J., Hornby,D.P., Grasby,J.A. and Williams,D.M. (2001) Enhancing the catalytic repertoire of nucleic acids: a systematic study of linker length and rigidity. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1565–1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jett J.H., Keller,R.A., Martin,J.C., Marrone,B.L., Moyzis,R.K., Ratliff,R.L., Seitzinger,N.K., Shera,E.B. and Stewart,C.C. (1989) High-speed DNA sequencing: an approach based upon fluorescence detection of single molecules. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn., 7, 301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stephan J., Dörre,K., Brakmann,S., Winkler,T., Wetzel,T., Lapczyna,M., Stuke,M., Angerer,B., Ankenbauer,W., Földes-Papp,Z. et al. (2001) Towards a general procedure for sequencing single DNA molecules. J. Biotechnol., 86, 255–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh D., Kumar,V. and Ganesh,K.N. (1990) Oligonucleotides, part 5+: synthesis and fluorescence studies of DNA oligomers d(AT)5 containing adenines covalently linked at C-8 with dansyl fluorophore. Nucleic Acids Res., 18, 3339–3345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randolph J.B. and Waggoner,A.S. (1997) Stability, specificity and fluorescence brightness of multiply-labeled fluorescent DNA probes. Nucleic Acids Res., 25, 2923–2929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu H., Chao,J., Patek,D., Mujumdar,R., Mujumdar,S. and Waggoner,A.S. (1994) Cyanine dye dUTP analogs for enzymatic labeling of DNA probes. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 3226–3232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu Z., Chao,J., Yu,H. and Waggoner,A.S. (1994) Directly labeled DNA probes using fluorescent nucleotides with different length linkers. Nucleic Acids Res., 22, 3418–3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Földes-Papp Z., Angerer,B., Ankenbauer,W. and Rigler,R. (2001) Fluorescent high-density labeling of DNA: error-free substitution for a normal nucleotide. J. Biotechnol., 86, 237–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Augustin M.A., Ankenbauer,W. and Angerer,B. (2001) Progress towards single-molecule sequencing: enzymatic synthesis of nucleotide-specifically labeled DNA. J. Biotechnol., 86, 289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Z. and Waggoner,A.S. (1997) Molecular mechanism controlling the incorporation of fluorescent nucleotides into DNA by PCR. Cytometry, 28, 206–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebeyehu G., Rao,P.Y., SooChan,P., Simms,D.A. and Klevan,L. (1987) Novel biotinylated nucleotide analogs for labeling and colorimetric detection of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res., 15, 4513–4534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Finckh U., Lingenfelter,P.A. and Myerson,D. (1991) Producing single-stranded DNA probes with the Taq DNA polymerase: a high yield protocol. Biotechniques, 10, 35–36, 38–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Földes-Papp Z., Angerer,B., Ankenbauer,W., Baumann,G., Birch-Hirschfeld,E., Björling,S., Conrad,S., Hinz,M., Rigler,R., Seliger,H. et al. (1998) Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy of enzymatic DNA polymerization. In Losa,G.A., Merlini,D., Nonnenmacher,T.F. and Wiebel,E.R. (eds), Fractals in Biology and Medicine. Birkhäuser, Basel, Vol. II, pp. 238–254.

- 22.Angerer B. (1999) High density labeling of DNA with modified or ‘chromophore’ carrying nucleotides and DNA polymerases used. US Patent Application, WO 1999/4780/00.

- 23.Krantz R. (1997) Synthesis of fluorophore-labeled DNA. US Patent Application, WO 1997/39150.

- 24.Hiyoshi M. and Hosoi,S. (1994) Assay of DNA denaturation by polymerase chain reaction-driven fluorescent label incorporation and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Anal. Biochem., 221, 306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunkel T.A. and Wilson,S.H. (1998) DNA polymerases on the move. Nature Struct. Biol., 5, 95–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spratt T.E. (2001) Identification of hydrogen bonds between Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment) and the minor groove of DNA by amino acid substitution of the polymerase and atomic substitution of the DNA. Biochemistry, 40, 2647–2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mossi R., Keller,R.C., Ferrari,E. and Hübscher,U. (2000) DNA polymerase switching: II. Replication factor C abrogates primer synthesis by DNA polymerase alpha at a critical length. J. Mol. Biol., 295, 803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sundquist W.I. and Klug,A. (1989) Telomeric DNA dimerizes by formation of guanine tetrads between hairpin loops. Nature, 364, 825–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karthikeyan G., Chary,K.V. and Rao,B.J. (1999) Fold-back structures at the distal end influence DNA slippage at the proximal end during mononucleotide repeat expansions. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 3851–3858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Viguera E., Canceill,D. and Ehrlich,S.D. (2001) In vitro replication slippage by DNA polymerases from thermophilic organisms. J. Mol. Biol., 312, 323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folsom V., Hunkeler,M.J., Haces,A. and Harding,J.D. (1989) Detection of DNA targets with biotinylated and fluoresceinated RNA probes. Effects of the extent of derivitization on detection sensitivity. Anal. Biochem., 182, 309–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holtke H.J., Seibl,R., Burg,J., Mühlegger,K. and Kessler,C. (1990) Non-radioactive labeling and detection of nucleic acids. II. Optimization of the digoxigenin system. Biol. Chem., 371, 929–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]