Abstract

Past studies have noted a digital divide, or inequality in computer and Internet access related to socioeconomic class. This study sought to measure how many households in a pediatric primary care outpatient clinic had household access to computers and the Internet, and whether this access differed by socio-economic status or other demographic information. We conducted a phone survey of a population-based sample of parents with children ages 0 to 11 years old. Analyses assessed predictors of having home access to a computer, the Internet, and high-speed Internet service.

Overall, 88.9% of all households owned a personal computer, and 81.4% of all households had Internet access. Among households with Internet access, 48.3% had high speed Internet at home. There were statistically significant associations between parental income or education and home computer ownership and Internet access. However, the impact of this difference was lessened by the fact that over 60% of families with annual household income of $10,000–$25,000, and nearly 70% of families with only a high-school education had Internet access at home.

While income and education remain significant predictors of household computer and internet access, many patients and families at all economic levels have access, and might benefit from health promotion interventions using these modalities.

INTRODUCTION

Differences in computer use and access related to socio-economic status have been described since the 1990’s.1,2 This “digital divide” has been confirmed in numerous studies. The 2000 Census found that although about half of all United States homes had computers, households with lower incomes were much less likely to own computers than were higher income households.3 Internet access was found in 86.3% of households earning at least $75,000 annually, compared to only 12.7% of households earning less than $15,000. 3 These numbers are in flux, however. Household computer ownership has increased dramatically in the last fifteen years, from 15% in 1989 to 22.8% in 1993, to 51% in 2000. 3

Some believe that by 2010 almost one-third of a physician’s time will be spent using information technology, and that 20% of office visits will be replaced by home Internet monitoring.5 Physicians appear to be well equipped technologically for this. A survey of physician practices in 2001 found that 94% had computers, and over three-quarters of all physician offices had Internet access.6 Unfortunately, pediatric patients and their families are often not as well supplied with technology. This disparity has the potential to leave certain patients behind .7

The percentage of households having computers can vary greatly depending on the population being surveyed.1,3–5,8–10 The proportion of pediatric patients and families with Internet access is unknown, and may reflect differences in age, gender, education, or socioeconomic status. This information is important, because computer use is becoming more prevalent in pediatric care. Since children may be drivers of both computer ownership and internet access, it is reasonable to conjecture that these may be higher in a pediatric population than in the population generally.

We recently described the attitudes of a large pediatric clinic population towards computers and the Internet, and how they use these tools.11 The question of attitudes has clinical and research relevance, as clinics and researchers install internet-ready computer kiosks in clinics, shopping malls, and other public places. However, information on computer ownership and home Internet access are the factors usually used to describe the digital divide, and have importance independent of attitudes. The objective of this study was to measure how many households in a diverse pediatric outpatient clinic had home access to computers and the Internet, and if this access differed by socio-economic status.

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional survey by telephone. The study design was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Our sample of potential participants was derived from parents of children ages birth to 10 years whose children had made at least one visit between 2000 and 2003 to the University of Washington Physician Network (UWPN), a physician-run organization of eight primary care clinics located throughout King County, Washington, and affiliated with the University of Washington Medical Center. These primary care clinics are staffed by both family physicians and pediatricians, and are not resident teaching clinics. The clinics are located in diverse environments with respect to patient race, age, and socio-economic status.

The telephone survey asked parent respondents to report on the presence of a computer and on Internet access in their home. It also asked if the household had high speed (broadband) Internet access. Finally, demographic variables including parental educational status, household income, race, and number of children in household were obtained. Information was also obtained on other health status variables for use in other investigations. The survey was conducted by the Northwest Research Group, an experienced and licensed survey group that has conducted thousands of phone surveys. A full copy of the survey is too long to be included with this report, but will be provided upon request.

The three primary outcomes of this study were home computer ownership, home Internet access, and home high-speed Internet access.

Multivariate logistic regression was used to assess predictors of household computer, Internet, and high-speed Internet access. All analyses were conducted using STATA 8.0 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

Initial letters were mailed to 5772 families. Of these, 1262 (22%) were returned with no forwarding address, and 357 (6%) opted out of the study immediately. Phone calls were made to the remaining 4153 telephone numbers on file. Of these, 801 (19%) were incorrect or disconnected numbers, 591 (14%) were repeatedly busy or not answered , 682 (16%) were made to families whose children no longer attended the UWPN clinic or were too old for study entry criteria, and 181 (4%) were excluded because no one answering the phone spoke English. Of 1898 families who were eligible and contacted, 1200 completed surveys. Calculation of response rates for telephone survey research is controversial, and the American Association of Public Opinion Research recommends that two rates be calculated and reported using two different denominators.12

The more commonly used method ignores unscreened households and counts only known eligible households in the denominator. In this study this method would yield 1200/1898 or 63%. However, some eligible households were likely in the group of those that were never screened by telephone. The second method attempts to account for this by including an estimate of those that were not screened but may have been eligible, based on the proportion in the screened population that was eligible. In this study, 57% of screened patients were eligible. Hence, of the 357 families that opted out immediately and the 591 families who were not screened we might expect 540 to be eligible (0.57 x 948). Using this methodology, our response rate was 1200/(1898+540)=50%.

Summary statistics for the study population are detailed in Table 1. Also shown are comparable statistics for the local population taken from the 2001 Supplemental Survey Profile of the U.S. Census.13 Median household income of our study group was $25,000 – $50,000, while the median household income of families in the local population was $66,580.13 Twenty-seven percent of the study sample had a high school education or less, while 42% had a college degree or greater (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population compared with 2000 census statistics for the Seattle-Bellevue-Everett, Washington MSA.

| Variable | Study Population N=1200 | Seattle-Bellevue-Everett Census |

|---|---|---|

| Mean patient Age (SD) | 5.4 yrs (3.2) | |

| Male (%) | 54% | |

| Mean number in Household (SD) | 4.1 (1.2) | |

| Parental Education | ||

| < high school | 6% | 10% |

| High school | 21% | 21% |

| Some College | 31% | 24% |

| College Degree | 30% | 33% |

| >College Degree | 12% | 12% |

| Annual Income | ||

| < $10 K | 6% | 3% |

| $10 K– $25 K | 15% | 9% |

| $25 K – $50 K | 30% | 23% |

| $50 K – $75 K | 25% | 23% |

| > $75 K | 24% | 42% |

Overall, 88.9% of all households owned a personal computer, and 81.4% of all households had Internet access (Table 2). Among households with Internet access, 48.3% had high speed Internet at home, and 99% were able to supply their e-mail address.

Table 2.

Household computer ownership and Internet access. Sample proportions and Logistic Regression. We present Odds Ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Regressions controlled for parental education, household income, and number of household members.

| Variable | Percent Owning Home Computer | Adjusted Logistic Regression OR (95% CI) | % of computer owners with Home Internet Access | Adjusted Logistic Regression OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 88.9% | 81.4% | ||

| Parental Education | ||||

| < High School | 73.2% | 1 (Referent) | 49.3% | 1 (Referent) |

| High school graduate | 78.4% | 1.0 (0.5–2.0) | 68.2% | 1.6 (0.9–3.0) |

| Some College | 87.7% | 1.8 (0.9–3.7) | 80.2% | 2.6 (1.4–4.9) |

| College Degree | 96.2% | 3.7 (1.5–9.1) | 92.1% | 4.7 (2.3–9.6) |

| >College Degree | 97.9% | 6.5 (1.7–23.9) | 94.4% | 6.8 (2.6–17.8) |

| Annual Income | ||||

| < $10 K | 62.5% | 1 (Referent) | 43.8% | 1 (Referent) |

| $10 K – $25 K | 73.9% | 1.6 (0.8–3.1) | 60.6% | 1.9 (1.0–3.4) |

| $25 K – $50 K | 88.4% | 3.7 (2.0–7.0) | 77.4% | 3.5 (1.9–6.1) |

| $50 K – $75 K | 94.8% | 6.9 (3.2–15.1) | 90.4% | 7.6 (3.9–14.7) |

| > $75 K | 97.4% | 12.7 (4.6–34.8) | 96.6% | 18.4 (7.8–43.4) |

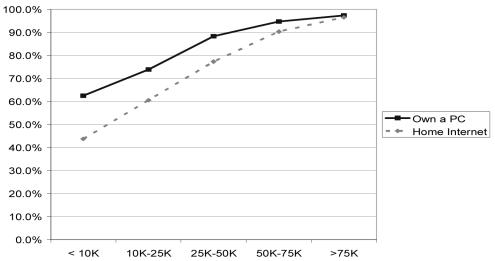

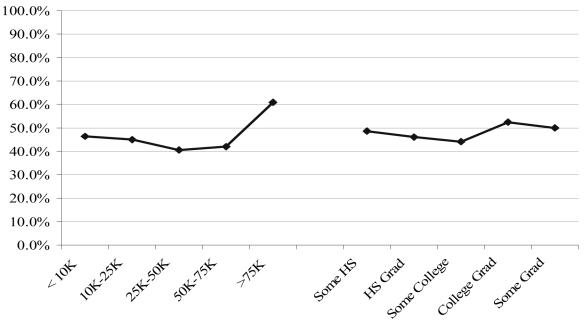

We found a significant positive relationship between income level and computer ownership and home Internet access (Figure 1). We found a similar positive relationship between education level and computer and Internet access. In a multivariate logistic regression model, owning a computer was associated with the number of people in the household [1.3 (1.1–1.5)] as well as household income and parental education (Table 2). In a similar model, having home Internet access was also associated with household size [1.1 (1.0–1.3)], household income, and parental education (Table 2). In contrast, none of these factors was significantly related to household access to high speed Internet access, as all education and household income groups were similar in the proportion of those with home Internet access having high speed access in their home (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Household computer ownership and Internet access by household income.

Figure 2.

Percentage of those with home Internet access having high speed access by income and education

DISCUSSION

A digital divide still exists in this pediatric clinic population. However, this divide is narrower than previously reported, as even 62.5% of households with the lowest income and 73.2% of parents without a high school education own a home computer.3 Fewer households had Internet access, but many more had access than has been previously reported.3 About half of all households with Internet access had high speed Internet access, irrespective of education and income level.

This study is subject to the limitations of phone surveys, including response bias. However, our response rate of between 50% and 63% is consistent with other published telephone surveys.14,15 We were not able to determine if respondents differed significantly from non-respondents, although they did not differ with respect to child age, clinic membership, or insurance type. It is also possible that responses to surveys may be prone to biases as families may reply with socially desirable answers. However, our questions were simple and straightforward, and, families were also asked to provide an internet address, reducing the likelihood of a false response to questions of computer ownership and internet access. In fact, 99% of subjects who reported having home Internet access were able to share their e-mail address. Most significantly, it is possible that our study population is somewhat atypical. Although, we drew from a large pediatric practice with a diverse patient population and wide geographic coverage, the results may not be generalizable to other areas of the country. We did, however, compare our study group to the local general population through census data, and found our study population to be generally of lower socio-economic status.

When considering health interventions using computers or the Internet, it is important to have an accurate sense of how patients will have access to them. A pediatric patient’s family is likely to be younger than the average American household, which may be associated with computer ownership. It is also possible that households with children are more likely to have computers or Internet access. Children have always been early adopters of technology,16 and coupled with exposure to computers at school, they may have influence on household access. It is therefore critical to measure this specific population’s ability to access health information on computers or the Internet.

This study has a number of implications for health practitioners and investigators. From a clinical standpoint, the fact that such a large percentage of patients have home computers and Internet access suggests that the number of pediatric patients and families using the Internet to access health information will increase in the future. This is true even among lower income and less educated patients and families.

Many have posited that the digital divide poses a significant barrier to the use of computer or Internet in health care. Health care interventions using this technology could be unequally applied to those at different socio-economic or educational levels.17–19 Our study finds that while income and education remain significant predictors, many patients and families at all economic levels have computer access, and might benefit from such interventions. Our results also show that high-speed access, which many interventions might require, was equally prevalent across all demographic classes. The digital divide should not be seen as a barrier to developing health interventions using information technology. The gap appears likely to close in the near future.

This study illustrates that the digital divide is not a “one-size-fits-all” description. At a minimum, our results suggest that each clinic and practitioner must be careful when deciding whether their own patient population is able to access electronic health information at home. Furthermore, if reflective of larger national trends, our results suggest a rapidly closing disparity among home computer and Internet users, showing that computer ownership and home Internet access are much higher than previously measured across all socio-economic levels.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research was funded by a grant from the AHRQ to DAC (R01 HS13302-02).

REFERENCES

- 1.KIDS COUNT Snapshot. Available at: http://www.aecf.org/publications/data/snapshot_june2002.pdf Accessed December 10, 2004.

- 2.Becker HJ. Who's wired and who's not: children's access to and use of computer technology. Future Child. 2000;10(2):44–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Digital Divide Basics Fact Sheet. Available at: http://www.digitaldividenetwork.org/content/stories/index.cfm?key=168 Accessed December 10, 2004.

- 4.Home Computers and Internet Use in the United States: August 2000. Available at: http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/p23-207.pdf Accessed December 10, 2004.

- 5.Skinner H, Biscope S, Poland B. Quality of internet access: barrier behind internet use statistics. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(5):875–80. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell DS, Daly DM, Robinson P. Is there a digital divide among physicians? A geographic analysis of information technology in Southern California physician offices. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(5):484–93. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kassirer JP. Patients, physicians, and the Internet. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19(6):115–23. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.6.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stroetmann VN, Husing T, Kubitschke L, Stroetmann KA. The attitudes, expectations and needs of elderly people in relation to e-health applications: results from a European survey. J Telemed Telecare. 2002;8 (Suppl 2):82–4. doi: 10.1177/1357633X020080S238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray NJ, Klein JD, Cantrill JA, Noyce PR. Adolescent girls' use of the Internet for health information: issues beyond access. J Med Syst. 2002;26(6):545–53. doi: 10.1023/a:1020296710179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brodie M, Flournoy RE, Altman DE, Blendon RJ, Benson JM, Rosenbaum MD. Health information, the Internet, and the digital divide. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19(6):255–65. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.6.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll AE, Zimmerman FJ, Rivara FP, Ebel BE, Christakis DA. Perceptions about computers and the Internet in a pediatric clinic population. Ambulatory Pediatrics 2005:in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Research. AAoPO. Standards and best practices. Standard definitions: final dispositions of case codes and outcomes rates for surveys. Available at http://www.aapor.org/default.asp?page=survey_methods/standards_and_best_practices/standard_definitions Accessed December 10, 2004.

- 13.U.S. Census Bureau: American Community Survey. Available at: http://www.census.gov/acs/www/Products/Profiles/Single/2001/SS01/Tabular/385/38500US760276003.htm Accessed December 10, 2004.

- 14.Schwartz LM, Woloshin S, Fowler FJ, Jr, Welch HG. Enthusiasm for cancer screening in the United States. Jama. 2004;291(1):71–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson DE, Bland S, Powell-Griner E, Klein R, Wells HE, Hogelin G, et al. State trends in health risk factors and receipt of clinical preventive services among US adults during the 1990s. Jama. 2002;287(20):2659–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ling R. The diffusion of mobile telephony among Norweigan teens: A report from after the revolution. In: ICUST 2001. Paris, France; 2001.

- 17.Safran C. The collaborative edge: patient empowerment for vulnerable populations. Int J Med Inf. 2003;69(2–3):185–90. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(02)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gray JE, Safran C, Davis RB, Pompilio-Weitzner G, Stewart JE, Zaccagnini L, et al. Baby CareLink: using the internet and telemedicine to improve care for high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1318–24. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piette JD. Enhancing support via interactive technologies. Curr Diab Rep. 2002;2(2):160–5. doi: 10.1007/s11892-002-0076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]