Abstract

LMO2 and LMO4 are members of a small family of nuclear transcriptional regulators that are important for both normal development and disease processes. LMO2 is essential for hemopoiesis and angiogenesis, and inappropriate overexpression of this protein leads to T-cell leukemias. LMO4 is developmentally regulated in the mammary gland and has been implicated in breast oncogenesis. Both proteins comprise two tandemly repeated LIM domains. LMO2 and LMO4 interact with the ubiquitous nuclear adaptor protein ldb1/NLI/CLIM2, which associates with the LIM domains of LMO and LIM homeodomain proteins via its LIM interaction domain (ldb1-LID). We report the solution structures of two LMO:ldb1 complexes (PDB: 1M3V and 1J2O) and show that ldb1-LID binds to the N-terminal LIM domain (LIM1) of LMO2 and LMO4 in an extended conformation, contributing a third strand to a β-hairpin in LIM1 domains. These findings constitute the first molecular definition of LIM-mediated protein–protein interactions and suggest a mechanism by which ldb1 can bind a variety of LIM domains that share low sequence homology.

Keywords: ldb1/LIM domains/LMO2/LMO4/protein complex

Introduction

The regulation of many cellular processes is controlled by specific protein–protein interactions, and a number of protein domains have emerged as important structural motifs that mediate these interactions. The LIM domain is one such motif. These zinc-binding domains are found in proteins with roles in diverse fundamental biological processes including cell fate determination, trafficking, cytoskeletal organization and organ development (Bach, 2000). LIM domains have been classified according to sequence similarities into four types (types A–D), and LIM-containing proteins have been divided into three groups (Dawid et al., 1998). Group I proteins contain the LMO (or rhombotin), LIM homeodomain (LHX) and LIM kinase families, which each contain tandem type A and type B LIM domains close to their N-terminus. Group II proteins are cytoplasmic CRP-like proteins that contain type C LIM domains and Group III proteins are more heterogeneous, but their type D LIM domains share comparatively high sequence homology. The presence of tandem LIM domains in Group I LIM proteins confers the potential to engage in multiple protein–protein interactions. Indeed, LMOs are often found in multiprotein complexes (reviewed by Rabbitts, 1998) and have been thought of as docking stations upon which multiple proteins can assemble to regulate processes such as cell proliferation. All LMO and LHX proteins have the ability to interact with the nuclear adaptor protein ldb1. ldb1 is likely to be critical for LIM protein function, perhaps due to its ability to dimerize (Jurata et al., 1998) and thereby allow the formation of higher order functional complexes.

The LMO family comprises four members, LMO1–4, of which LMO2 (or rhombotin 2) is the best characterized. The gene for this protein was first identified in association with specific chromosomal translocations t(11;14)(p13; q11) that result in acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) in children (reviewed by Rabbitts, 1998). As part of its normal role, LMO2 is an essential regulator of hemopoiesis (Visvader et al., 1997; Yamada et al., 1998), and also of angiogenesis associated with both embryonic development (Yamada et al., 2000) and tumor growth (Yamada et al., 2002). LMO4 is the most recently identified member of the LMO family. It was originally identified as a breast cancer autoantigen (Racevskis et al., 1999) and has recently been shown to be overexpressed in >50% of primary breast cancers (Visvader et al., 2001). Both LMO4 and ldb1 appear to act as negative regulators of breast epithelial cell differentiation (Visvader et al., 2001), while LMO2 inhibits maturation of T lymphocytes (Rabbitts, 1998) and erythroid cells (Visvader et al., 1997). Displacement of LMO4 as the binding partner of ldb1 by overexpression of either LMO1 or LMO2 has been proposed as a mechanism for LMO-induced T-ALLs (Rabbitts, 1998). To help elucidate the mechanisms by which ldb1 and LMO proteins regulate normal and oncogenic developmental processes, we determined the structures of both LMO4:ldb1 and LMO2:ldb1 complexes.

These structures reveal that ldb1 recognizes both LMO2 and LMO4 by taking up an extended conformation and making both hydrophobic and electrostatic contacts along the entire long axis of the LIM domains. A number of backbone hydrogen bonds are also formed, providing an explanation for the fact that ldb1 can contact many LIM-containing proteins with diverse sequences.

Results and discussion

ldb1 binds to the N-terminal LIM domain of LMO4 with moderate affinity

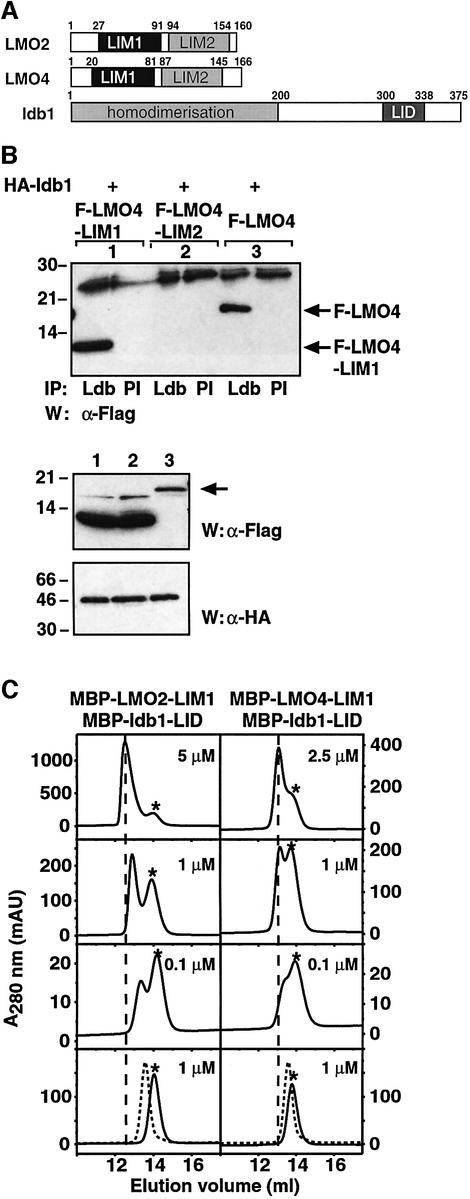

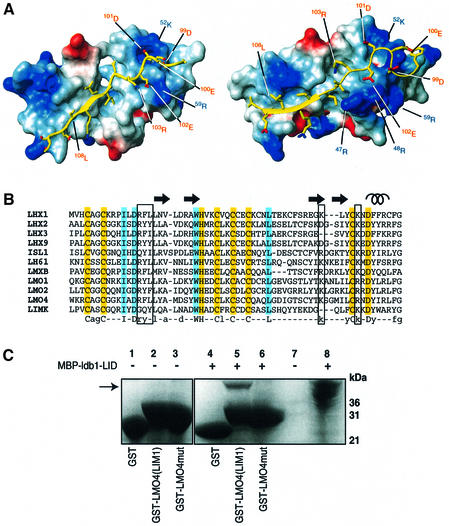

Using co-immunoprecipitation, GST-pulldown and yeast two-hybrid experiments, it has been shown that ldb1 binds with high affinity to the tandem LIM domain repeats of LMO and LHX proteins via the 39 residue LIM interaction domain in ldb1 (ldb1-LID) (Figure 1A) (Agulnick et al., 1996; Bach et al., 1997; Jurata and Gill, 1997; Visvader et al., 1997; Breen et al., 1998). ldb1 also binds to LIM1 of Isl1, LMO2 and X-Lim (Jurata et al., 1996; Jurata and Gill, 1997) and to the C-terminal LIM domain (LIM2) of LMX1 and MEC3 (Jurata and Gill, 1997; Breen et al., 1998). Through a series of GST-pulldown and co-immunoprecipitation experiments, we found that the LIM1 domains of both LMO2 and LMO4 bind to ldb1 with significantly higher affinity than their LIM2 domains (Figure 1B). Although most LMO polypeptides proved to be unstable, we purified small amounts of MBP–LMO2-LIM1 and MBP–LMO4-LIM1 (LMO2-LIM1 and LMO4-LIM1 fused to maltose binding protein, respectively) and examined complex formation by size-exclusion chromatography (Figure 1C). MBP–ldb1-LID and the MBP–LMO-LIM1 proteins all eluted at similar volumes (bottom panels, dotted and solid lines, respectively). Equimolar ratios of ldb1-LID/LMO-LIM1 at a range of different protein concentrations (∼0.1–5 µM) were applied to the column. At lower concentrations (∼0.1 µM, lower middle panels) the proteins eluted at the expected volumes for uncomplexed proteins, providing little evidence for complex formation. At higher concentrations (upper middle and top panels) the relative intensities of peaks corresponding to uncomplexed MBP–LMO-LIM1 decreased (asterisks) and peaks appeared with smaller elution volumes corresponding to the formation of LMO:ldb1 complexes (indicated by broken vertical lines). At protein concentrations of ∼1 µM (upper middle panels), ∼50% of each protein was present as complex, indicating that the affinity of both LMO2-LIM1 and LMO4-LIM1 for ldb1-LID is ∼106 M–1 under these conditions.

Fig. 1. Interaction between LMOs and ldb1 is mediated by a single LIM domain. (A) Schematic diagram of LMO2, LMO4 and ldb1. (B) Immunoprecipitation experiment. Human embryonal kidney (293T) cells were transfected with expression constructs encoding Flag-tagged derivatives of LMO4 representing either the single LIM domains [F-LMO4-LIM1 or F-LMO4-LIM2 (lanes 1 and 2, respectively)] or full-length protein (F-LMO4, lane 3), together with plasmid encoding HA-tagged ldb1. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and proteins were immunoprecipitated with pre-immune or anti-ldb1 antisera. Immuno blotting was performed with anti-Flag monoclonal antibody. Arrows indicate F-LMO4-LIM1 and F-LMO4. Western blot analysis of lysates confirmed expression of HA-ldb1 and Flag-LMO proteins (lower panels). The arrow depicts full-length LMO protein (17 kDa), while the lower bands correspond to individual LIM domains. (C) Size-exclusion chromatography. Isolated protein at ∼1 µM (bottom panels) or solutions containing equimolar concentrations of MBP–LMO2-LIM1 or MBP– LMO4-LIM1 and MBP–ldb1-LID at the indicated concentrations were applied to a Superose12™ size-exclusion column (Amersham Biosciences). The elution volumes of uncomplexed MBP–LMO-LIM1 proteins are indicated by an asterisk in each panel. Uncomplexed MBP–ldb1-LID is shown as a dotted chromatogram in the bottom panels. The elution volumes of the complexes are indicated by broken lines.

ldb1-LID is largely unfolded

Examination of recombinant ldb1-LID using far-UV circular dichroism (CD) and two-dimensional 1H NMR spectroscopy revealed that the peptide is largely unfolded under a wide range of solution conditions (data not shown). The only structure that could be detected was a small amount of nascent helix, deduced from the presence of dNN(i, i + 1) nuclear Overhauser effects (NOEs) in the region Asp316–Thr322 (Dyson et al., 1988). A longer construct, encompassing residues 267–375 of ldb1, had no additional structure, suggesting that ldb1-LID belongs to the growing class of proteins and protein domains that only assume ordered conformations upon binding (Dyson and Wright, 2002).

The structure of an LMO4-LIM1:ldb1-LID complex

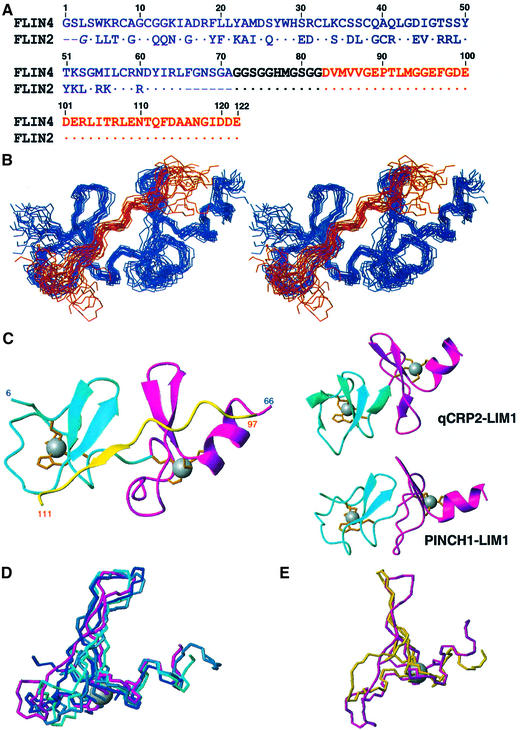

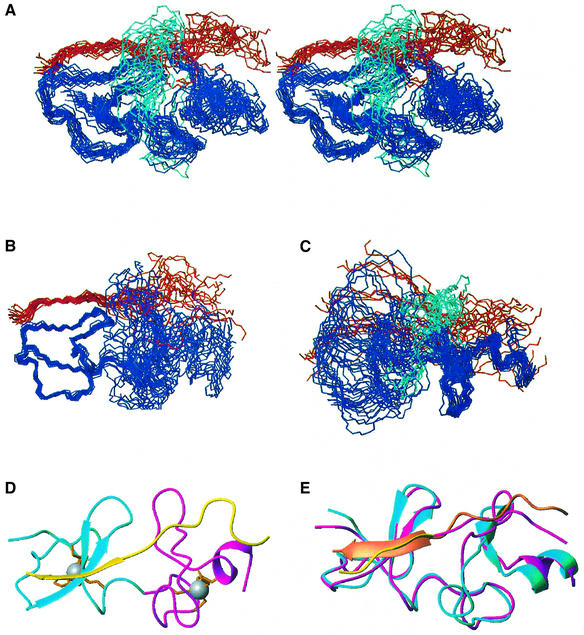

To overcome problems associated with the instability and insolubility of LMO proteins we designed two fusion proteins: FLIN2 (fusion of LID and the N-terminal LIM domain of LMO2) and its counterpart FLIN4 (Figure 2A) (Deane et al., 2001). In both cases the two domains were fused via an 11 residue flexible linker, with the LMO-LIM1 domain at the N-terminus. Note that the numbering of residues in this article is based on the FLIN4 construct shown in Figure 2A. The correspondences of this numbering system to the LMO2, LMO4 and ldb1 protein sequences (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession Nos BC035607, XM_030627 and NM_003893, respectively) are shown in the legend to Figure 2. We initially solved the structure of FLIN4 using restraints derived from multidimensional NMR spectroscopy (Table I), and the structure of this engineered protein reveals that ldb1-LID binds in an extended fashion along the longest axis of the LMO4-LIM1 domain (Figure 2B and C, PDB 1M3V).

Fig. 2. The solution structure of FLIN4. (A) Amino acid sequences of FLIN4 and FLIN2. Dashes indicate gaps in the sequence; dots are identical residues. Residues 1–71 of FLIN4 correspond to residues 16–86 of LMO4 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. XM_030627) with the mutations C37S/C49S, residues 72–82 constitute the linker, residues 83–122 correspond to residues 300–339 of ldb1 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. NM_003893). The same numbering is used for FLIN2; however, 3Gly comes from the polylinker region of the pGEX-2T plasmid, while residues 4–65 correspond to residues 26–87 of LMO2 (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession No. BC035607). Residues derived from LMO proteins are in blue, residues from ldb1 are in red and the linker is in black. (B) Stereo view of the structured regions of FLIN4 with the 20 lowest-energy structures overlaid on the backbone atoms of the LMO4-LIM1 domain. LMO4-LIM1 is shown in blue, while ldb1-LID is in red. (C) Ribbon diagrams showing a comparison of FLIN4 (left) with LIM domains from qCRP2-LIM1 (Kontaxis et al., 1998) (right, upper, 1A71) and PINCH1-LIM1 (Velyvis et al., 2001) (right, lower; 1G47). Zn1 is shown in cyan, Zn2 in magenta and ldb1 in yellow. Zinc-ligating side chains are shown in orange. (D) Comparison of CCCC [mGATA-1 N-finger, dark blue, 1GNF (Kowalski et al., 1999); cGATA-1 C-terminal finger, mid-blue, 1GAT (Omichinski et al., 1993); Zn2 from qCRP2-LIM1, cyan] and CCCD (Zn2 from FLIN4, magenta) modules. Only the zinc ion from FLIN4 is shown for clarity. Backbone r.m.s.d. over residues 34–38 and 50–65 (or equivalent) is 0.96 Å. (E) Comparison of CCCD (Zn2 from FLIN4, magenta) and CCCH (PINCH1-LIM1, yellow) overlaid over same residues.

Table I. Statistics for the ensembles of FLIN2 and FLIN4 structures.

| |

FLIN2 |

FLIN4 |

| Experimental input |

|

|

| Total NOE restraints | 1690 | 1885 |

| Total unambiguous restraints | 1640 | 1804 |

| Intraresidue | 809 | 951 |

| Sequential (|i – j| = 1) | 414 | 410 |

| Medium range (2 < |i – j| < 3) | 267 | 226 |

| Long range (|i – j| > 3) | 160 | 217 |

| Total ambiguous restraints | 50 | 81 |

| Torsion angle constraints | ||

| φ | 67 | 58 |

| ψ | 50 | 37 |

| χ1 |

17 |

17 |

| Quality control |

|

|

| PROCHECK statistics | ||

| Structured regionsa | ||

| Residues in most favored regions (%) | 68.6 | 75.2 |

| Residues in allowed regions (%) | 24.0 | 23.5 |

| Residues in generously allowed regions (%) | 5.5 | 0.8 |

| Residues in disallowed regions (%) | 1.9 | 0.5 |

| R.m.s.d. of backbone atoms | ||

| Structured regionsa | 1.62 ± 0.46 | 0.99 ± 0.21 |

| First Zn-binding moduleb | 0.39 ± 0.15 | 0.64 ± 0.24 |

| Second Zn-binding modulec | 1.24 ± 0.30 | 0.80 ± 0.24 |

| R.m.s.d. of all heavy atoms | ||

| Structured regionsa | 1.98 ± 0.49 | 1.50 ± 0.24 |

| First Zn-binding moduleb | 0.87 ± 0.28 | 1.24 ± 0.30 |

| Second Zn-binding modulec | 1.85 ± 0.31 | 1.26 ± 0.29 |

| Mean deviations from ideal geometry | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.00463 ± 0.00033 | 0.00439 ± 0.00067 |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.646 ± 0.030 | 0.623 ± 0.164 |

aResidues 6–40, 49–65 and 105–112 in FLIN2 and residues 8–66 and 104–109 in FLIN4 have order angle parameters for φ and ψ >0.8.

bResidues 8–32 in FLIN2 and in FLIN4.

cResidues 35–40 and 49–63 in FLIN2 and residues 35–66 in FLIN4.

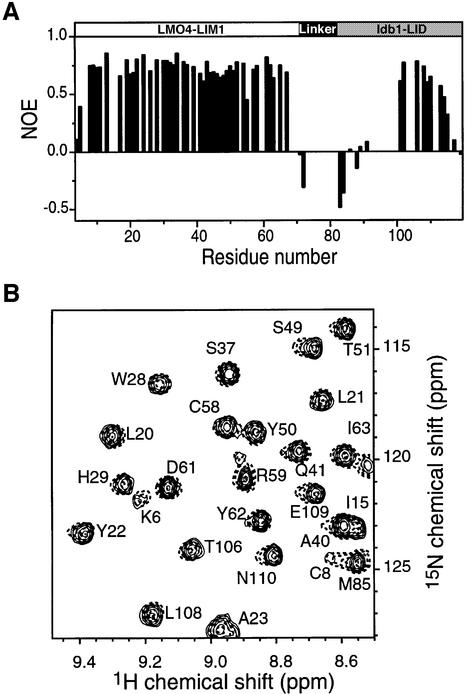

In order to establish whether the intramolecular interaction observed here accurately represents the natural intermolecular interaction, we considered several factors. From previous work, we know that the ldb1 binding site is blocked in the FLIN proteins: FLIN proteins cannot bind free ldb1 in GST pull-down experiments (Deane et al., 2001). In FLIN4, the engineered linker region (72Gly– 82Gly) and the first 14 residues of ldb1-LID (83Asp–96Glu) appear to be largely unstructured, judging from the narrow linewidths, lack of non-sequential NOEs, random coil chemical shifts and the magnitude of 15N-1H steady-state NOEs in this region (Figure 3A). The resulting segment of at least 24 flexible residues should provide sufficient conformational freedom to allow ldb1-LID to bind the LIM domain in any orientation. As final confirmation, we generated a 15N-labeled variant of FLIN4 in which we replaced part of the linker with a Factor Xa protease site. 15N HSQC spectra from this variant before (as an intramolecular complex) and after (as an intermolecular complex) protease treatment are essentially identical (Figure 3B), showing that the relative orientations of the LIM1 domain and ldb1-LID are equivalent in both intra- and intermolecular complexes (complete proteolysis was confirmed by SDS–PAGE). A similar approach was recently adopted in studies of the N-WASP EVH1:WIP peptide complex (Volkman et al., 2002).

Fig. 3. The linker region of FLIN4 is unstructured and does not affect the LMO4-LIM1:ldb1-LID complex. (A) Heteronuclear 15N–1H NOE data for FLIN4. NOE values were calculated as the ratio of peak intensities with and without proton saturation and plotted as a function of residue number. Data were only calculated from those residues that had well-resolved amide peaks. (B) Overlay of part of the 15N HSQC spectrum of FLIN4 containing a Factor Xa protease site (FLIN4-Xa, line) with that of the same protein following treatment with Factor Xa (dashes). The chemical shifts of peaks from FLIN4-Xa are identical to those obtained for FLIN4. Over 90% proteolysis was achieved according to analysis by SDS–PAGE.

Comparisons with other LIM structures

Structures of type C and D LIM domains from Group II and III proteins have been determined previously and these show that LIM domains contain two sequential zinc-binding modules, Zn1 and Zn2 (Perez-Alvarado et al., 1996; Konrat et al., 1998; Kontaxis et al., 1998; Yao et al., 1999; Velyvis et al., 2001). LMO4-LIM1 is the first type A/Group I member to have its structure determined, and it exhibits a similar topology to the Group II and Group III structures (Figure 2C). Both Zn1 and Zn2 contain two short β-hairpins, although only the C-terminal β-hairpins in each module (21Leu–23Ala/26Ser–28Trp and 50Tyr–52Lys/55Met–57Leu, respectively) are recognized by the Kabsch–Sander algorithm (Kabsch and Sander, 1983) in the majority of calculated conformers. Zn2 also contains a short C-terminal β-helix (61Asp–65Leu).

The zinc coordination sphere of Zn1 in FLIN4 (8Cys, 11Cys, 29His, 32Cys) takes up an essentially identical conformation to those found in other LIM domains, while the coordination sphere in Zn2 (35Cys, 38Cys, 58Cys, 61Asp) comprises the CCCD module found only in Group I LIM domains. It is notable that, for the PINCH1-LIM1 structure, although Zn2 appears to have a CCCD module based on sequence comparisons, the NMR structure of this domain indicates that the fourth zinc-ligating residue is in fact an unusually spaced histidine side chain (Velyvis et al., 2001). Thus the structure presented here is the first example of a zinc-binding domain that coordinates a structural zinc ion with an oxygen ligand. This module takes up a conformation almost identical to that of CCCC modules found in GATA proteins and Group II LIM domains (Figure 3D). Both types of module have the same ‘treble clef’ fold consisting of two short β-hairpins followed by an α-helix. The lengths and relative orientations of these features are very similar. The main difference between the two modules is the conformation of the loop between the two β-hairpins; the CCCD module in LMO4-LIM1 has an additional two residues in this loop compared with most CCCC modules. In contrast, the unusual spacing of the Group III PINCH LIM1 (C-X2-C-X15-C-X-H versus C-X2-C-X15–17-C-X2-C/D) appears to cause an increase in the angle between the second β-hairpin and the α-helix (Figure 2E).

A small hydrophobic core is formed in Zn1 of LMO4-LIM1 by residues packing around the side chain of 28Trp. This residue is fully conserved amongst Group I LIM domains; members of Groups II and III have a phenylalanine or tyrosine in this position. The hydrophobic core of Zn2 is very similar to that found in Group II LIM domains, although it forms around 57Leu rather than an aromatic side chain.

A commonly observed feature of LIM domains is conformational flexibility. For example, 15N backbone dynamics and mutational studies of CRP2 (Konrat et al., 1998; Kontaxis et al., 1998; Kloiber et al., 1999; Schuler et al., 2001) have shown that the two zinc-ligating modules have both internal and intermodule flexibility, as well as plasticity within the hydrophobic cores. This flexibility has been proposed to contribute to LIM-mediated protein–protein interactions, perhaps by allowing optimization of interfaces between proteins. In our structure of FLIN4, the relative orientation of the two zinc-ligating modules of LMO4-LIM1 is significantly different from that observed in free LIM domains (Figure 2C), even taking into account the fact that different LIM domains from both Group II and Group III show some variation themselves. Thus the angle through which one module must be rotated to overlay the other ranges between 20 and 60° for Group II and Group III LIM domains, while the angle in LMO4-LIM1 is ∼110°. The relative positions of these modules are defined largely by restraints derived from LIM:ldb1-LID NOEs rather than LIM:LIM NOEs (Figure 4). This suggests that formation of the LMO4:ldb1 complex is at least partly responsible for the relative orientation of the two zinc-binding modules and that in free LMO4 these modules may have increased mobility with respect to one another. However, there is still considerable flexibility between the two zinc-binding modules, as indicated both by 15N relaxation data (Figure 3A; data not shown) and by the reduction in root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) that is observed for the FLIN4 ensemble when it is overlaid on individual zinc-binding modules (the backbone r.m.s.d. is 0.64 Å over Zn1, 0.80 Å over Zn2 and 0.99 Å over LIM1 + ldb1-LID). These data also reveal that small loops between elements of defined secondary structure in LMO4-LIM1 are relatively mobile when compared with the core regions of the domain. Attempts to measure residual dipolar coupling for FLIN4 as additional determinants of relative orientation of Zn1, Zn2 and ldb1-LID were unsuccessful due to the interaction of the protein with bicelles.

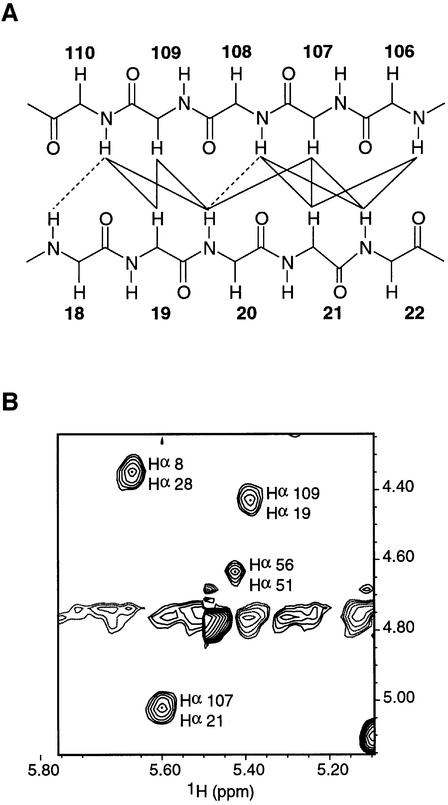

Fig. 4. The ldb1-LID forms an additional β-strand. (A) Schematic diagram showing observed NOEs between the β-strand in ldb1-LID and the second β-hairpin in LMO4-LIM1. Observed NOEs are shown as bold lines; NOEs that may be present but obscured by spectral overlap are shown as broken lines. Only backbone atoms are shown; side chains have been omitted for simplicity. (B) Hα–Hα NOEs from a 2D homonuclear NOESY spectrum of FLIN4.

The structure of an LMO2:ldb1-LID complex

In order to understand further the nature of the LIM:ldb1 interactions and to identify any differences between the two interactions that might be exploited in the design of specific LMO2 or LMO4 inhibitors, we also determined the structure of FLIN2 using the same methodology (Table I; Figure 5, PDB 1J2O). The structure of FLIN2 is well defined in the first zinc-binding domain (Figure 5B; backbone r.m.s.d. 0.39 Å) but has more variation between ensemble family members in the second zinc-binding domain (Figure 5C; backbone r.m.s.d. 1.24 Å over structured residues). No peaks from residues 41–48 are visible in triple resonance experiments. These residues form a loop (Figure 5A and C, cyan) that connects two β-hairpins in Zn2. Peaks from residues at the ends of the loop are very broad but have chemical shifts that vary significantly from those expected for random coil, as do a number of weak peaks visible in homonuclear spectra that originate from residues within the loop. This suggests that the residues 41–48 in FLIN2 are probably undergoing some sort of chemical exchange process on the microsecond–millisecond time scale.

Fig. 5. The solution structure of FLIN2. (A) Stereo view of the structured regions of FLIN2 with the 20 lowest-energy structures overlaid over the backbone atoms of the LMO2-LIM1 domain (residues 6–40 and 49–65). LMO2-LIM is shown in blue, ldb1 is shown in red and residues 41–48 are shown in cyan. (B) The same structures overlaid on the backbone atoms of the first zinc-binding module of LMO2-LIM1. (C) The same structures overlaid on the backbone atoms of the second zinc-binding module of LMO2-LIM1. Residues 41–48 are shown in cyan. (D) Ribbon diagram showing FLIN2. Zn1 is shown in cyan, Zn2 in magenta and ldb1 in yellow. Zinc-ligating side chains are shown in orange. (E) Ribbon diagrams showing a comparison of FLIN2 and FLIN4, FLIN2 is in magenta and orange, and FLIN4 is in cyan and yellow. The structures are overlaid using the backbone atoms of the structured regions of the LIM domains.

The sequences of LMO2-LIM1 and LMO4-LIM1 are 47% identical in the regions used in this study (Figure 2A). The fold of FLIN2 is essentially identical to that of FLIN4 (Figure 5D and E). The proteins share an overall backbone r.m.s.d. of 1.8 Å (0.88 Å over the Zn1 modules). In each structure, the same residues form the basis of the hydrophobic cores and the orientation of the two zinc-binding modules with respect to each other is also identical.

The LIM:ldb1-LID interaction

In both FLIN2 and FLIN4, ldb1-LID stretches across both zinc-binding modules to bury ∼1800 and ∼1500 Å2 of surface area, respectively (Figure 6A). However, the nature of the interaction with each of the zinc-binding modules appears to be strikingly different. Interactions between ldb1-LID and Zn1 are predominantly backbone mediated (Figure 4) or hydrophobic in nature; ldb1–LID contributes a third short β-strand (107Arg–108Leu for FLIN4 and 106Thr–109Glu for FLIN2) to the well-defined C-terminal β-hairpin in Zn1 and forms a series of mainly hydrophobic side chain interactions centered on 19Phe. As ldb1-LID extends along Zn2, the mode of binding becomes less well defined, as judged by the variation between different members of the ensemble, and increasingly electrostatic in nature. In FLIN4, a series of mainly acidic residues on ldb1-LID (pI ≈ 3.5) forms two complementary electrostatic patches with Zn2: 99Asp and 101Asp interact with 52Lys, while 100Glu, 102Glu and 103Arg form an extended network of electrostatic interactions with 59Arg. It is widely accepted that electrostatic interactions make a substantial contribution towards the specificity of complex formation (Sheinerman et al., 2000). Furthermore, it is recognized that, although individual ion pairs may have destabilizing effects on protein stability owing to desolvation effects, networks of electrostatic interactions can stabilize proteins and protein complexes (Sheinerman et al., 2000).

Fig. 6. Binding of ldb1-LID to LMO-LIM1. (A) Surface potential figure of LMO4-LIM1 (left) and LMO2-LIM1 (blue positive, red negative) drawn using MOLMOL (Koradi et al., 1996); ldb1 is in yellow. Residues from ldb1 are labeled in red, and residues from LMO4 and LMO2 are labeled in blue. (B) Sequence comparison of Group I LIM1 domains. Well-defined regions of secondary structure in FLIN4 are indicated with arrows for β-strands and a coil for the α-helix. Hydrophobic residues and positively charged residues that appear to mediate the LMO4-LIM1:ldb1 interaction are boxed. Zinc-ligating residues are highlighted in yellow, while other fully conserved residues are highlighted in cyan. In a consensus sequence of LMO and LHX LIM1 domains, well-conserved residues are indicated in lower-case letters. (C) Specificity of ldb1 binding. SDS–PAGE analysis shows the relative binding of MBP–ldb1-LID (arrow) to immobilized GST, GST-LMO4-LIM1 and GST-LMO4mut. Components of lanes 1–6 are indicated, lane 7 carried molecular weight markers and lane 8 shows 5% input of MBP–ldb1-LID.

Interestingly, the acidic stretch of residues in ldb1-LID forms a series of small turns in the FLIN structures, consistent with the nascent helical conformation inferred for the uncomplexed ldb1-LID from NMR and CD data. This suggests that there may be some pre-ordering of ldb1-LID, although a comparison of medium-range NOE patterns in the free and complexed forms shows that this pre-organization is only partial. It is notable that, using the Chou–Fasman and Garnier–Osguthorpe–Robson methods in PEPTIDESTRUCTURE (Jameson and Wolf, 1988), this region is strongly predicted to form α-helical secondary structure, indicating the difficulty in distinguishing α-helices from a series of turns based on sequence information alone.

Specificity of ldb1-LIM interactions

LMO and LHX proteins are members of Group I LIM proteins and all can bind ldb1. An additional member of the same group, LIM kinase (LIMK), does not bind to ldb1. We compared the LIM1 sequences of a series of LHX/LMO proteins that have been experimentally shown to bind ldb1 with the sequence of LIMK (Figure 6B). There are few non-zinc-ligating residues that are fully conserved among the Group I LIM domains. However, there is a region that is highly conserved in LHX/LMO proteins but not in LIMK. This region is close to the first well-defined β-hairpin, where side chain interactions from LMO4-LIM1 and LMO2-LIM1 appear to stabilize the interaction with the additional β-strand in ldb1-LID. In the LMO/LHX proteins this motif is R(Y/F)L, while in LIMK it is GQY. The loss of a bulky and an aromatic side chain in those positions would result in the loss of a hydrophobic region that may be required to stabilize the interaction. Furthermore, while both LMO/LHX and LIMK domains bear positively charged residues at or near 52Lys and 59Arg that could form ionic interactions with the highly acidic ldb1-LID domain, it is notable that the LIMK domain is slightly acidic whereas the LMO/LHX domains are slightly basic. Consequently, there could be a net electrostatic attraction between the latter domains and ldb1-LID that would not exist in the case of LIMK. To investigate whether such an electrostatic interaction would be sufficient to mediate the LIM:ldb1 interaction, we made a version of LMO4-LIM1 in which four residues were mutated to their LIMK counterparts, R18G/F19Q/L20Y/Y22Q (LMO4mut). For this mutant the interaction with ldb1-LID is abolished, as demonstrated by GST-pulldown experiments (Figure 6C), indicating that the R(Y/F)L sequence is important for determining LMO/LHX specificity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have revealed the mechanism through which ldb1 recognizes LMO proteins. A combination of electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions results in the burial of a relatively large surface area, given the size of the domains involved. It is also possible that the binding event may induce a change in the relative conformations of the two zinc-binding modules in LMO4, although this remains to be confirmed. Interestingly, the only other data available on a LIM domain interaction (Velyvis et al., 2001), that between PINCH-LIM1 and the integrin-linked kinase ankyrin repeat domain, also indicated the formation of a large interaction interface and/or conformational changes.

LMO proteins can interact simultaneously with multiple proteins. The presence of a double LIM domain in the LMO proteins makes it tempting to speculate that LIM1 binds to one partner protein, while LIM2 mediates binding to a different partner protein. However, this is likely to be an oversimplification. LMO4 can interact directly and simultaneously with breast-cancer-associated protein 1 (BRCA1), CtIP and ldb1 (Sum et al., 2002). Furthermore, the LMO4:CtIP interaction is independently mediated by LMO4-LIM1, suggesting that ldb1-LID and CtIP bind to different faces of LMO4-LIM1. Our structure of FLIN4 shows that ldb1-LID binds to a single face of LMO4- LIM1, leaving a large surface area comprising flexible loop regions that may contact CtIP or other proteins.

Our results should provide insight into specific molecular mechanisms used by nuclear regulatory complexes in the control of gene expression patterns. In order to treat diseases such as T-cell leukemia and breast cancer, a detailed molecular understanding of these mechanisms will be required; the structure of these LMO-ldb1 complexes represents a first step in this direction.

Materials and methods

Immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down assays

Human embryonal kidney 293T cells were transiently transfected with 2–3 µg of each expression construct using Fugene (Roche). Cell extracts were prepared and proteins immunoprecipitated and separated as described previously (Sum et al., 2002). After transfer to PVDF membranes (Millipore), filters were blocked and incubated with mouse anti-Flag monoclonal antibody (Sigma). Filters were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-coupled secondary antibodies, and developed by ECL (Amersham Biosciences). For GST pull-down assays, LMO proteins were produced as GST fusions and immobilized on GSH beads (Amersham Biosciences). Beads containing equivalent amounts of protein were added to the soluble fraction of lysate containing overexpressed MBP–ldb1-LID, incubated for 1 h at 4°C and washed with buffer containing 20 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.1% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma) and 5 µM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The amount of bound MBP– ldb1-LID was visualized using SDS–PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining, or by western blotting using anti-MBP primary antibodies and HRP-coupled secondary antibodies, and developed by ECL (Amersham Biosciences).

Protein preparation and gel filtration

Protein ldb1-LID was prepared as a GST fusion protein using a pGEX-2T protein expression vector in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3). The peptide was purified by GSH affinity chromatography, followed by proteolysis with thrombin and RP-HPLC. FLIN2 and FLIN4 were prepared as described previously (Deane et al., 2002). MBP–LMO4-LIM1 and MBP–ldb1-LID were prepared from pMAL-c2X constructs (New England Biolabs) with a modified polylinker. Proteins were purified by amylose affinity chromatography, followed by anion-exchange and size-exclusion chromatography. Equimolar mixtures of MBP–LMO4-LIM1 and MBP–ldb1-LID at different concentrations were applied to a Superose12™ column (Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated with 20 mM Na2HPO4, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) pH 8.0 and running at 0.5 ml/min.

Far-UV CD spectropolarimetry

CD spectra were recorded on a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter equipped with a Neslab RTE-111 temperature controller. CD data were collected over the wavelength range 195–260 nm with a resolution of 0.5 nm, a bandwidth of 1 nm and a response time of 1 s. Final spectra were the sum of three scans accumulated at a speed of 20 nm/min and were baseline corrected.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR samples contained 0.2–1 mM protein in solutions of 20 mM Na2HPO4 (95% H2O–5% D2O) pH 7.0, 1 mM DTT and 50 mM NaCl + DSS/TSP. All NMR spectra were acquired at 25°C on Bruker DRX-600 NMR spectrometers. Spectra were processed and analyzed and backbone/side chain 1H, 15N and 13C resonances were assigned as described previously (Deane et al., 2002). NOE-derived distance restraints were obtained from three-dimensional (3D) 15N-edited NOESY and two-dimensional (2D) 1H-NOESY spectra. φ-angle restraints were calculated based on the 3JHNH α coupling constants measured from a 3D HNHA (Bax et al., 1994). Stereospecific Hβ assignments and χ1 restraints were obtained from a combination of 3D HNHB (Bax et al., 1994) and short-mixing-time NOESY (τmix = 30 ms) and TOCSY (τmix = 35 ms) spectra. Additional φ and χ restraints were included based on analysis of 1HN, 15N, 13C′, 13Cα and 13Cβ chemical shifts in the program TALOS (Cornilescu et al., 1999). Heteronuclear steady-state 1H–15N NOEs were calculated from a pair of spectra and the steady-state NOE values were recorded with and without proton saturation (Farrow et al., 1994; Ottiger et al., 1998).

Structure calculations

Iterative manual assignment of NOEs was used to calculate initial structures of FLIN4 using the program DYANA (Guntert et al., 1997). A total of 58 φ, 37 ψ and 17 χ1 angle constraints were included in structure calculations with a precision of ±40°. Further refinement was conducted in an automated manner using ARIA (Nilges et al., 1997) implemented in CNS 1.1 (Brünger et al., 1998). In the first iteration, 150 structures were calculated using the manually assigned NOEs as soft restraints. The cut-off value of an ambiguous assignment was reduced from 1.01 for the first iteration to 0.80 in iteration 8. A total of 1804 unambiguous and 81 ambiguous restraints were identified by ARIA, and these were checked and corrected manually where necessary. The 20 members of the final ensemble of conformers had no distance restraints violated by >0.5 Å. The quality of the structures was assessed using PROCHECK-NMR (Laskowski et al., 1996). The structures of FLIN2 were calculated in the same manner but with the angle restraints and NOEs described in Table I.

Factor Xa proteolysis

An NMR sample of uniformly 15N-labeled FLIN4 (200 µM) containing a Factor Xa protease site was prepared. A mass ratio of 1:50 of Factor Xa to protein was added at 25°C. Proteolysis was allowed to proceed for 20 h. 15N HSQC spectra were recorded prior to the addition of Factor Xa, at hourly intervals for the first 12 h of proteolysis and at the completion of proteolysis. Samples for analysis were taken at the same times, the reaction was stopped by the addition of SDS loading buffer and samples were analysed by Tris–tricine SDS–PAGE to determine the extent of proteolysis.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr David Gell for help in establishing suitable conditions for MBP–LMO4 proteins and Dr Bill Bubb for expert maintenance of the spectrometer at the University of Sydney. Dr Peter Karuso is thanked for access to the spectrometer at Macquarie University. J.E.D., A.H.Y.K. and E.Y.M.S. are supported by Australian Postgraduate Awards. J.E.V. is supported by the Victorian Breast Cancer Research Consortium. J.M.M. is an Australian Research Fellow. This work was supported by grants from the Australian Research Council and the Leo and Jenny Foundation.

References

- Agulnick A.D., Taira,M., Breen,J.J., Tanaka,T., Dawid,I.B. and Westphal,H. (1996) Interactions of the LIM-domain-binding factor ldb1 with LIM homeodomain proteins. Nature, 384, 270–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach I. (2000) The LIM domain: regulation by association. Mech. Dev., 91, 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach I., Carriere,C., Ostendorff,H.P. Andersen,B. and Rosenfeld,M.G. (1997) A family of LIM domain-associated cofactors confer transcriptional synergism between LIM and Otx homeodomain proteins. Genes Dev., 11, 1370–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bax A., Vuister,G.W., Grzesiek,S., Delaglio,F., Wang,A.C., Tschudin,R. and Zhu,G. (1994) Measurement of homo- and heteronuclear J couplings from quantitative J correlation. Methods Enzymol., 239, 79–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen J.J., Agulnick,A.D., Westphal,H. and Dawid,I.B. (1998) Interactions between LIM domains and the LIM domain-binding protein Ldb1. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 4712–4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A.T. et al. (1998) Crystallography and NMR System (CNS): a new software system for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D, 54, 905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornilescu G., Delaglio,F. and Bax,A. (1999) Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR, 13, 289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawid I.B., Breen,J.J. and Toyama,R. (1998) LIM domains: multiple roles as adapters and functional modifiers in protein interactions. Trends Genet., 14, 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane J.E., Sum,E., Mackay,J.P., Lindeman,G.J., Visvader,J.E. and Matthews,J.M. (2001) Design, production and characterization of FLIN2 and FLIN4: the engineering of intramolecular LMO/ldb1 complexes. Protein Eng., 14, 493–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deane J.E., Visvader,J.E., Mackay,J.P. and Matthews,J.M. (2002) 1H, 15N and 13C assignments of FLIN4, an intramolecular LMO4:ldb1 complex. J. Biomol. NMR, 23, 165–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson H.J. and Wright,P.E. (2002) Coupling of folding and binding for unstructured proteins. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 12, 54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson H.J., Rance,M., Houghten,R.A., Wright,P.E. and Lerner,R.A. (1988) Folding of immunogenic peptide fragments of proteins in water solution. II. The nascent helix. J. Mol. Biol., 201, 201–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow N.A. et al. (1994) Backbone dynamics of a free and phosphopeptide-complexed Src homology 2 domain studied by 15N NMR relaxation. Biochemistry, 33, 5984–6003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guntert P., Mumenthaler,C. and Wuthrich,K. (1997) Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol., 273, 283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson B.A. and Wolf,H. (1988) The antigenic index: a novel algorithm for predicting antigenic determinants. Comput. Appl. Biosci., 4, 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata L.W. and Gill,G.N. (1997) Functional analysis of the nuclear LIM domain interactor NLI. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 5688–5698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata L.W., Kenny,D.A. and Gill,G.N. (1996) Nuclear LIM interactor, a rhombotin and LIM homeodomain interacting protein, is expressed early in neuronal development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 11693–11698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurata L.W., Pfaff,S.L. and Gill,G.N. (1998) The nuclear LIM domain interactor NLI mediates homo- and heterodimerization of LIM domain transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 3152–3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. and Sander,C. (1983) Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers, 22, 2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloiber K., Weiskirchen,R., Krautler,B., Bister,K. and Konrat,R. (1999) Mutational analysis and NMR spectroscopy of quail cysteine and glycine-rich protein CRP2 reveal an intrinsic segmental flexibility of LIM domains. J. Mol. Biol., 292, 893–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrat R., Krautler,B., Weiskirchen,R. and Bister,K. (1998) Structure of cysteine- and glycine-rich protein CRP2. Backbone dynamics reveal motional freedom and independent spatial orientation of the lim domains. J. Biol. Chem., 273, 23233–23240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontaxis G., Konrat,R., Krautler,B., Weiskirchen,R. and Bister,K. (1998) Structure and intramodular dynamics of the amino-terminal LIM domain from quail cysteine- and glycine-rich protein CRP2. Biochemistry, 37, 7127–7134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi R., Billeter,M. and Wüthrich,K. (1996) MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph., 14, 51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski K., Czolij,R., King,G.F., Crossley,M. and Mackay,J.P. (1999) The solution structure of the N-terminal zinc finger of GATA-1 reveals a specific binding face for the transcriptional co-factor FOG. J. Biomol. NMR, 13, 249–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski R.A., Rullmannn,J.A., MacArthur,M.W., Kaptein,R. and Thornton,J.M. (1996) AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR, 8, 477–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilges M., Macias,M.J., O’Donoghue,S.I. and Oschkinat,H. (1997) Automated NOESY interpretation with ambiguous distance restraints: the refined NMR solution structure of the pleckstrin homology domain from beta-spectrin. J. Mol. Biol., 269, 408–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omichinski J.G., Clore,G.M., Schaad,O., Felsenfeld,G., Trainor,C., Appella,E., Stahl,S.J. and Gronenborn,A.M. (1993) NMR structure of a specific DNA complex of Zn-containing DNA binding domain of GATA-1. Science, 261, 438–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottiger M., Delaglio,F. and Bax,A. (1998) Measurement of J and dipolar couplings from simplified two-dimensional NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson., 131, 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Alvarado G.C., Kosa,J.L., Louis,H.A., Beckerle,M.C., Winge,D.R. and Summers,M.F. (1996) Structure of the cysteine-rich intestinal protein, CRIP. J. Mol. Biol., 257, 153–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitts T.H. (1998) LMO T-cell translocation oncogenes typify genes activated by chromosomal translocations that alter transcription and developmental processes. Genes Dev., 12, 2651–2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racevskis J., Dill,A., Sparano,J.A. and Ruan,H. (1999) Molecular cloning of LMO41, a new human LIM domain gene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1445, 148–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler W., Kloiber,K., Matt,T., Bister,K. and Konrat,R. (2001) Application of cross-correlated NMR spin relaxation to the zinc-finger protein CRP2(LIM2): evidence for collective motions in LIM domains. Biochemistry, 40, 9596–9604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheinerman F.B., Norel,R. and Honig,B. (2000) Electrostatic aspects of protein–protein interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol., 10, 153–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sum E.Y., Peng,B., Yu,X., Chen,J., Byrne,J., Lindeman,G.J. and Visvader,J.E. (2002) The LIM domain protein LMO4 interacts with the cofactor CtIP and the tumor suppressor BRCA1 and inhibits BRCA1 activity. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 7849–7856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velyvis A., Yang,Y., Wu,C. and Qin,J. (2001) Solution structure of the focal adhesion adaptor PINCH LIM1 domain and characterization of its interaction with the integrin-linked kinase ankyrin repeat domain. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 4932–4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader J.E., Mao,X., Fujiwara,Y., Hahm,K. and Orkin,S.H. (1997) The LIM-domain binding protein Ldb1 and its partner LMO2 act as negative regulators of erythroid differentiation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 13707–13712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visvader J.E. et al. (2001) The LIM domain gene LMO4 inhibits differentiation of mammary epithelial cells in vitro and is overexpressed in breast cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 14452–14457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkman B.F., Prehoda,K.E., Scott,J.A., Peterson,F.C. and Lim,W.A. (2002) Structure of the N-WASP EVH1 domain-WIP complex. Insight into the molecular basis of Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome. Cell, 111, 565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y., Warren,A.J., Dobson,C., Forster,A., Pannell,R. and Rabbitts,T.H. (1998) The T cell leukemia LIM protein Lmo2 is necessary for adult mouse hematopoiesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 95, 3890–3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y., Pannell,R., Forster,A. and Rabbitts,T.H. (2000) The oncogenic LIM-only transcription factor Lmo2 regulates angiogenesis but not vasculogenesis in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 97, 320–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y., Pannell,R., Forster,A. and Rabbitts,T.H. (2002) The LIM-domain protein Lmo2 is a key regulator of tumour angiogenesis: a new anti-angiogenesis drug target. Oncogene, 21, 1309–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao X., Perez-Alvarado,G.C., Louis,H.A., Pomies,P., Hatt,C., Summers,M.F. and Beckerle,M.C. (1999) Solution structure of the chicken cysteine-rich protein, CRP1, a double-LIM protein implicated in muscle differentiation. Biochemistry, 38, 5701–5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]