Abstract

The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum is a well-established model organism for the study of basic aspects of differentiation, signal transduction, phagocytosis, cytokinesis and cell motility. Its genome is being sequenced by an international consortium using a whole chromosome shotgun approach. The pacemaker of the D.discoideum genome project has been chromosome 2, the largest chromosome, which at 8 Mb represents ∼25% of the genome and whose sequence and analysis have been published recently. Chromosomes 1 and 6 are close to being finished. To accelerate completion of the genome sequence, the next step in the project will be a whole-genome assembly followed by the analysis of the complete gene content. The completed genome sequence and its analysis provide the basis for genome-wide functional studies. It will position Dictyostelium at the same level as other model organisms and further enhance its experimental attractiveness.

Keywords: chromosome shotgun/Dictyostelium discoideum/genome/model organism/sequencing

The organism

Dictyostelium discoideum is an excellent model system for studying fundamental cellular processes as well as aspects of multicellular development. Its natural habitat is deciduous forest soil and decaying leaves, where the amoeboid cells feed on bacteria and multiply by equal mitotic division. Exhaustion of the food source triggers a developmental programme, in which up to 100 000 cells aggregate by chemotaxis to form a multicellular structure that undergoes morphogenesis and cell type differentiation (Figure 1). Development culminates in the production of spores that enable the organism to survive unfavourable environmental conditions. The cells are amenable to diverse biochemical, molecular genetic and cell biological approaches, which allow dissection of the molecular interactions underlying cytokinesis, cell motility, chemotaxis, phagocytosis, signal transduction and aspects of development such as cell sorting, pattern formation and cell type differentiation. Dictyostelium was also described as a suitable host for pathogenic bacteria in which one can conveniently study the process of infection (Skriwan et al., 2002). Considering the impact on disease-related genes that has been made by the yeast genome project, another advance on disease as well as on infection-associated mechanisms is expected from the Dictyostelium genome project (Saxe, 1999; Glöckner et al., 2002; Williams et al., 2002).

Fig. 1. Dictyostelium discoideum fruiting bodies. The image shows wild-type fruiting bodies that are characterized by long, thin stalks and globular spore heads containing highly resistant spores. Picture credit: Dr M.Schleicher, ABI/Cell Biology, LMU Munich.

Dictyostelium discoideum is haploid, and therefore mutants can be easily generated. The molecular genetic techniques available include gene inactivation by homologous recombination, gene replacement, antisense strategies, restriction enzyme-mediated integration (REMI), library complementation and expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion proteins (Eichinger et al., 1999). Recently it was shown that RNA interference (RNAi), a technique to silence genes efficiently, can also be applied to Dictyostelium (Martens et al., 2002). The ease with which the genome can be manipulated is surpassed only by that of Saccharomyces cerevisiae but, unlike yeast, D.discoideum is motile, phagocytic and also exists as a multicellular organism which undergoes differentiation and development. Moreover, Dictyostelium can be grown easily in large quantities, facilitating biochemical analysis. In addition, Dictyostelium strains can be frozen away like Escherichia coli and stored for many years, thus enabling scientists to work with unchanged geno- and phenotypes over long time periods.

The D.discoideum genome

The Dictyostelium genome is between 34 and 40 Mb in size and contains six chromosomes ranging from 4 to 8 Mb (Cox et al., 1990; Kuspa and Loomis, 1996). In addition, the nucleus harbours ∼100 copies of a small palindromic extrachromosomal element of ∼90 kb that carries the rRNA genes. The chromosomes are believed to be acro- or telocentric, with the centromere embedded in a large cluster of long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (DIRS-1) composed of >40 elements. However, so far, the fine structure of neither the centromere nor the telomeres has been resolved.

Several families of interspersed repetitive elements have been described, and altogether these elements occupy 10% of the Dictyostelium chromosomes (Glöckner et al., 2001). Overall, the proportion of complex repetitive elements in the Dictyostelium genome is high compared with S.cerevisiae, Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila melanogaster. With an average A + T content of 78%, the nucleotide composition of the Dictyostelium chromosomes is extremely biased. Among genome sequences available to date, this high A + T content is exceeded only by Plasmodium falciparum with 80% (Gardner et al., 2002). The gene structure is fairly simple in D.discoideum; introns are not very frequent, and with ∼100 bases they are usually quite short and flanked by the universal splice site donor and acceptor consensus sequences. In conjunction with a considerably higher than average A + T content in introns and intergenic regions, these properties make gene prediction in D.discoideum comparatively straightforward.

Organization and strategy of the project

To provide the basis for genome-wide investigations, a joint international effort to sequence the genome of D.discoideum, strain AX4, was initiated from independent groups in Germany, the UK and the USA in 1998 (Table I). As a service to the scientific community and similarly to many other genome projects, it was decided to release D.discoideum sequence data immediately. To maximize the potential use of the genome sequence and its annotation, the data will be transferred upon completion to dictyBase (http://dictybase.org/), an on-line bioinformatics resource that organizes and presents genomic, genetic, phenotypic and functional information for D.discoideum. In addition, dictyBase provides database support and the Internet point of access for the D.discoideum stock centre under development at Columbia University in the USA.

Table I. The Dictyostelium genome sequencing consortium.

| Project partner | Responsibility | Chromosomea | Starting year | Project website |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Cologne, Cologne, GermanyGenome Sequencing Center, Jena, Germany | Sequencing, assembly, annotation | 1, 2 and 3 | 1998 | http://www.uni-koeln.de/dictyostelium/http://genome.imb-jena.de/dictyostelium/ |

| Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA | Sequencing, assembly, annotation | 4 and 2/3 of 6 | 1998 | http://dictygenome.bcm.tmc.edu/ |

| Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UKUniversity of Dundee, Dundee, UKMedical Research Council, Cambridge, UK | Sequencing, assembly, annotation | 5 | 2000 | http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_discoideum/ |

| EUDICT Consortiumb | Sequencing, assembly, annotation | 1/3 of 6 | 1998 | http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_discoideum/ |

| Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA | Separation of chromosomes | 1–6 | 1998 | http://www.molbio.princeton.edu/research_facultymember.php?id=22 |

| Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UK | Library preparation | 1–6 | 1998 | http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_discoideum/ |

| Medical Research Council, Cambridge, UK | Genome-wide HAPPY map | 1–6 | 1998 | http://www.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk:80/happy/happy-home-page.html |

| Northwestern University, Chicago, IL, USA | dictyBase, curation of genomic data | 1–6 | 2002 | http://dictybase.org/ |

| University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba, Japan | cDNA project | ESTs | 1996 | http://www.csm.biol.tsukuba.ac.jp/cDNAproject.html |

aBased on the YAC physical map by Kuspa and Loomis (1996), the chromosome sizes in Mb are as follows: C1, 5.5; C2, 6.9; C3, 5.3; C4, 6.2; C5, 5.3; C6, 4.1.

bMembers of the EUDICT consortium: Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UK; University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany; Pasteur Institute, Paris, France; University of Dundee, Dundee, UK; Medical Research Council Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.

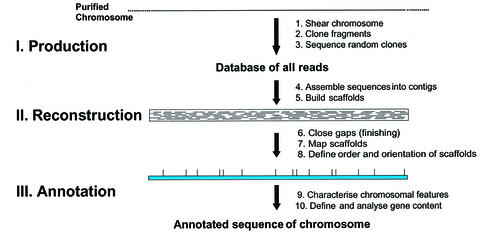

Sequencing and assembly of the Dictyostelium genome was expected to be a major challenge due to the extreme compositional bias of the DNA, the relatively large chromosomes and the presence of numerous, highly conserved and large complex repetitive elements. Moreover, the very high A + T content of up to 98% in intergenic regions causes instability of plasmid inserts longer than ∼5 kb in E.coli, and meant that large insert bacterial clones commonly used as second source templates in large-scale shotgun sequencing projects could not be generated. It also resulted in a sequence and clone bias, which is directed against AT-rich regions and further complicates the assembly. To reduce the complexity of the assembly task, the Dictyostelium genome sequencing consortium decided to shotgun sequence the genome chromosome by chromosome, a strategy that had already been used successfully with a similarly difficult genome, that of P.falciparum (Gardner et al., 2002; Figure 2; Table I; see also http://www.uni-koeln.de/dictyostelium/consortium.shtml). Testing of the chromosome-enriched libraries revealed that they were only partially pure (∼60%), and also contained clones derived from the other chromosomes as well as mtDNA and rDNA as contaminants. This had several consequences: first, considerably more reads than originally calculated had to be generated to reach sufficient coverage for completion of the first sequenced chromosomes, chromosomes 2 and 6. Secondly, each sequencing centre produced a large amount of reads that were not part of its project but belonged to any of those chromosomes that were assigned to project partners. Finally, special assembly strategies had to be developed to filter out contaminant reads and to anchor contigs.

Fig. 2. Steps in a WCS approach. Three main phases, production, reconstruction and annotation, are distinguished. The starting material is a purified chromosome, which is physically sheared. A homogeneous population of small fragments is obtained that are cloned into a suitable sequencing vector. The cloned fragments are selected randomly for sequencing, forward and reverse sequencing reactions are performed with standard primers, and the sequences are stored in a database. After an 8- to 10-fold coverage is reached, the sequences are assembled with computer programs. Contigs, i.e. contiguous DNA sequences, are generated from which scaffolds are built through the incorporation of read pair information. In the reconstruction phase, gaps are closed, scaffolds mapped and the order and orientation of scaffolds are defined. In the final phase, the annotation phase, gene models and other features of the chromosome are defined and analysed. The final goal is the complete annotated sequence of the chromosome.

Chromosome 2

For the assembly of chromosome 2, an iterative and integrated assembly strategy was used successfully (Glöckner et al., 2002). It is characterized by the definition of seed clones in the beginning, a BLAST-based repeated assembly cycle to bin reads into the assembly database, the removal of non-chromosomal contigs based on the relative frequencies of the constituent sequences from all chromosomally enriched libraries, and the construction of scaffolds through incorporation of read pair information and extensive manual editing. Integrating results from physical mapping allowed us to anchor and order contigs along the chromosome and robustly to assemble 6.5 of the 8.1 Mb chromosome.

Chromosome 2 harbours 73 tRNA genes and 2799 predicted protein-coding genes. Compared with other fully sequenced eukaryotes, this results in a surprisingly high gene density of one gene per 2.6 kb, which is surpassed only by S.cerevisiae (one per 2.0 kb) and similar to Schizosaccharomyces pombe (one per 2.5 kb) (Goffeau et al., 1996; Wood et al., 2002). If we assume a similar gene density for all chromosomes, then we expect ∼11 000 genes in the D.discoideum genome, approximately twice as many as in yeast and close to the 13 600 in Drosophila (Goffeau et al., 1996; Adams et al., 2000). Verification of predicted protein-coding genes was supported by BLAST searches and data from the Japanese expressed sequence tag (EST) project, which so far has revealed unique sequences of >50% of all genes (Morio et al., 1998). In total, EST, protein and/or InterPro matches provide support for 1960 (70%) of the 2799 predicted proteins. Based on InterPro results and the gene ontology (GO; http://www.geneontology.org/) terminology, 37% of the predicted proteins could be grouped into the cellular process and/or molecular function groups. Of the proteins in the cellular process group, 9.14% are dedicated to cell communication and involved in signal transduction or cell adhesion, or comprise cytoskeletal proteins containing signalling domains. This number is remarkably high and most probably reflects the fact that D.discoideum undergoes differentiation and development.

Among these proteins, we have found several new signalling proteins, and five of these are additional members of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family. GPCRs currently are subdivided into six families that show no sequence similarity to each other (Bockaert and Pin, 1999). In Dictyostelium so far, only four members of one family, the cAMP receptor family, have been described and studied extensively. Surprisingly, the newly discovered GPCRs belong to family 3 and have highest homology to GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid) type B receptors, which have not yet been observed outside the metazoan branch. The sequence similarity is restricted to the seven transmembrane domains and has, with ∼45–50%, the highest similarity to the human, rat, mouse and D.melanogaster subtype 1 and 2 GABAB receptors. Four of the novel Dictyostelium heptahelical receptors are closely related and share between 40 and 65% sequence identity over the complete length of the protein, and three of these are located directly behind each other on the chromosome. The fifth receptor is more divergent and only ∼30% identical with any of the other four proteins. We also searched all available project data and found that there are at least 12 such receptors in the entire genome. In metazoa, the GABAB receptor is a metabotropic receptor that couples to Ca2+ and K+ channels via heterotrimeric G-proteins and second messenger systems. In its native form, the GABAB receptor is a heterodimer of subtype 1 and 2 in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio. The large N-terminal extracellular domain of the GABAB subtype 1 receptor shares some sequence and structural similarity to the binding domains of metabotropic glutamate receptors and bacterial periplasmic amino acid-binding proteins (Blein et al., 2000). Interestingly, the N-terminal domains of three of the putative Dictyostelium receptors display some limited but significant sequence similarity with the basic membrane protein family of bacterial outer membrane proteins. Four of the receptors appear more closely related to subtype 2, while the fifth receptor displays a slightly higher similarity to subtype 1 GABAB receptors. At present, we do not know the functions of these receptors in Dictyostelium; however, one attractive possibility is that they might be sensors for folate and other small molecules.

Dictyostelium cells are highly motile and their motility characteristics are very similar to those of human leukocytes (Devreotes and Zigmond, 1988). Con sequently, the genome harbours a large number of genes encoding cytoskeletal proteins. For example, there are ∼27 actin genes in the complete genome; 13 are located on chromosome 2, and 10 of these translate into an identical protein (Glöckner et al., 2001, 2002). In addition, we have also found several genes coding for motor proteins, among which are six genes for different unconventional myosins. One of these unconventional myosin genes was not known before, and we have also discovered putative paralogues of fimbrin, profilin I/II and cofilin 1/2 on chromosome 2 (Table II). This finding was quite surprising because the cytoskeleton is a major area of Dictyostelium research. The discovery of additional paralogues for cytoskeletal proteins supports the concept of functional redundancy in the cytoskeletal system (Witke et al., 1992). Assuming that genes are distributed equally over the genome, we expect at least 10 new paralogues of known cytoskeletal proteins in the remainder of the genome.

Table II. Genes on chromosome 2 encoding cytoskeletal proteins.

| Gene | Copy number |

|---|---|

| Actin | 13 |

| Unconventional myosins (total) | 6 |

| RMLC | 1 |

| MHCK | 1 |

| MLCK | 1 |

| Cortexillin II | 1 |

| Protovillin | 1 |

| KHC | 1 |

| DHC | 1 |

| γ-tubulin | 1 |

| Unconventional myosin | 1 |

| Fimbrin homologue | 1 |

| Profilin homologue | 1 |

| Cofilin homologue | 1 |

In addition to previously characterized genes encoding cytoskeletal proteins, there are four new paralogues on chromosome 2 (italics). RMLC, regulatory myosin light chain; MHCK, myosin heavy chain kinase; MLCK, myosin light chain kinase; KHC, kinesin heavy chain; DHC, dynein heavy chain.

Phylogenetic considerations

Genome sequencing increasingly will provide the ultimate evidence from which the deep branching of the eukaryotic Tree of Life can be understood. The genome of an organism contains evidence not only of the branching of the tree, but also for the processes by which it was shaped. These include sequence change, gene loss, horizontal transfer, duplications, transpositions, symbiotic events and the evolution of analogous functions. In this respect, the sequence of chromosome 2 of Dictyostelium provides important new information, as it is the first from a free-living protozoan (Glöckner et al., 2002).

The long-standing controversy over the evolutionary position of Dictyostelium has been fuelled by contradicting phylogenies and phylogenetically conflicting properties of this organism. As a consequence, the position of the Phylum Amoebozoa, to which Dictyostelium belongs, is still uncertain. Based on morphological criteria, the Amoebozoa could be rooted at the base of bikont evolution. However, this evidence is weak and neither divergence before the common ancestor of Bikonts (Plantae) and Opisthokonts (Animalia and Fungi) nor a cladistically closer relationship to animals and fungi can be excluded (Stechmann and Cavalier-Smith, 2002). Most protein data, however, support the view that Dictyostelium is more closely related to Opisthokonts than to Plantae. Probably most convincing are results based on the analysis of combined protein data sets which robustly place the Amoebozoa as a sister group to the Opisthokonts (Baldauf et al., 2000; Bapteste et al., 2002). This grouping is reflected very well by the regulatory pathways that control the Dictyostelium developmental cycle (Parent and Devreotes, 1996). We applied a simple BLAST approach to establish the number of genes held in common (above a certain BLAST threshold) between representatives of different lineages and used this as a measure of relatedness. The result showed that Dictyostelium chromosome 2 has considerably more protein similarities with metazoa (850) than plants (737), but less with fungi (610) and also slightly more with vertebrates (677) than with D.melanogaster (668) and C.elegans (657) (Glöckner et al., 2002). Two conclusions emerge: first, the results suggest a closer functional relationship of Dictyostelium to animals than to plants or fungi. This unexpected conclusion for the fungal lineage may be due largely to gene loss and higher evolutionary rates of individual genes. Therefore, we think that this piece of evidence supports a tree in which branching of Dictyostelium antedated the divergence of Animalia and Fungi but occurred after the divergence of the Plantae. Secondly, the number of genes held in common between Dictyostelium and vertebrates makes Dictyostelium a suitable model organism for investigating a number of conserved eukaryotic functions that cannot be investigated in yeast.

The next step—analysis of the total gene content

Up to now, the sequencing consortium generated ∼1 000 000 high quality sequence reads on chromosome-enriched libraries and on a whole genome library. Thus, the shotgun sequencing phase is finished for all six D.discoideum chromosomes and the overall coverage of the genome is ∼10-fold. Improvements in sequencing technology, computer hardware and assembly algorithms make a whole genome assembly even for the extremely difficult D.discoideum genome feasible. For the assembly, which will be carried out at the Sanger Institute, available good quality reads from the project partners will be pooled and assembled using read pair information. Contigs and scaffolds will be anchored and oriented through the incorporation of relevant mapping information from the HAPPY and YAC physical maps as well as from already finished contigs from the whole chromosome shotgun (WCS) projects (Kuspa and Loomis, 1996; Konfortov et al., 2000; Glöckner et al., 2002). Finished regions will be distributed among the project partners according to their responsibility, and a common set of tools for gene prediction, analysis and annotation will be used. We envision that in this way the completion of the D.discoideum genome will be considerably accelerated.

The future—genome-wide functional analysis

Fully annotated genome sequences have become available recently for several eukaryotes. For the human and the rice genomes, well advanced working drafts are available (Lander et al., 2001; Goff et al., 2002). The analysis of these data revealed that even highly complex organisms apparently encode far fewer genes than originally thought. The increasing complexity within organisms might therefore be generated at the transcriptional and post-transcriptional level and by novel interactions between proteins and separation of components in space and time. The analysis also showed that the basic cellular machinery is composed of mainly the same genes in all organisms, while specific requirements and abilities are reflected by the vast abundance of species-specific genes.

Based on biochemical and/or genetic evidence and sequence homology, possible functions at present can only be assigned to a subfraction of all the predicted genes in a genome. For the majority of all the genes, the function remains to be understood. It is one of the major challenges of the post-genome era to assign functions to the thousands of genes that make up individual genomes and to try to understand how they and their products work in a coordinated manner in order to allow cells to respond to signals, grow, multiply and form tissues. The availability of complete genome sequences for a number of model organisms invites global approaches that address most or all genes and their gene products at once. In recent years, several high throughput techniques have been developed in order to study transcriptional regulation as well as protein interaction on a large scale. The first eukaryote genome published was the yeast genome (Goffeau et al., 1996), and it is in yeast where most of these powerful new approaches are pioneered. For example, the completed yeast genome sequence provided the basis for the development and design of the first high density DNA microarrays to study genome-wide transcriptional regulation (DeRisi et al., 1997). In addition, large-scale two-hybrid approaches as well as systematic identification of protein complexes by mass spectrometry were used to create protein linkage maps (Gavin et al., 2002). Each of these techniques has its advantages and limitations in addition to specific shortcomings. General problems of all high throughput technologies are the intrinsic impossibility of detecting all possible interactions and the presence of an unknown fraction of false positives. Furthermore, the evaluation and interpretation of the results of only one technique will deliver only part of the picture, and complex cellular processes cannot be fully understood. In order to get rid of the background noise and to obtain a more complete picture of complex cellular processes, it is necessary to integrate and analyse the results from different large-scale approaches (Ge et al., 2001). In the coming years, we probably will see a refinement of these genome-scale methods in conjunction with improved approaches to integration.

We anticipate that the full gene content of the D.discoideum genome will be available in 2003. All sequence data as well as the results of the automatic annotation will be transferred to dictyBase (http://www.dictybase.org), an integrated database of D.discoideum, where the genomic and EST data are manually curated and linked with experimental results and available publications. From the very beginning, the ongoing genome and EST projects have had a strong impact on current and new research projects in the community. A wealth of sequence information became available at a very fast pace, making it possible to carry out in silico searches for conserved orthologues or even full pathways and to analyse complete gene families (Rivero et al., 2001; Anjard et al., 2002). The available sequence data already paved the way for transcriptional studies encompassing approximately half of all the genes in the genome (Van Driessche et al., 2002). In addition, a proteomics project has been started in Australia. This is clearly only the beginning, and it is without doubt that the functional analysis of D.discoideum will profit enormously from methodological improvements of large-scale approaches in other organisms. The completed genome sequence will constitute the source for basic biological and biomedical research, for genome-wide comparisons between phylogenetically related groups, and functional analyses of the transcriptome and the proteome. It will propel D.discoideum into a new era of research and further enhance the attractiveness of this fascinating organism that lies at the border between single-celled and multicellular organisms.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Dictyostelium genome sequencing consortium for their contributions to the joint project and Dr Gernot Glöckner in addition for his input to Figure 2. The Dictyostelium genome project is funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the National Institutes of Health, the Medical Research Council and the European Union. Support of Köln Fortune is also acknowledged.

References

- Adams M.D. et al. (2000) The genome sequence of Drosophila melanogaster. Science, 287, 2185–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anjard C., the Dictyostelium Sequencing Consortium and Loomis,W.F. (2002) Evolutionary analyses of ABC transporters of Dictyostelium discoideum. Eukaryot. Cell, 1, 643–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldauf S.L., Roger,A.J., Wenk-Siefert,I. and Doolittle,W.F. (2000) A kingdom-level phylogeny of eukaryotes based on combined protein data. Science, 290, 972–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bapteste E. et al. (2002) The analysis of 100 genes supports the grouping of three highly divergent amoebae: Dictyostelium, Entamoeba and Mastigamoeba. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 1414–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blein S., Hawrot,E. and Barlow,P. (2000) The metabotropic GABA receptor: molecular insights and their functional consequences. Cell Mol. Life Sci., 57, 635–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockaert J. and Pin,J.P. (1999) Molecular tinkering of G protein-coupled receptors: an evolutionary success. EMBO J., 18, 1723–1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox E.C., Vocke,C.D., Walter,S., Gregg,K.Y. and Bain,E.S. (1990) Electrophoretic karyotype for Dictyostelium discoideum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 87, 8247–8251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRisi J.L., Iyer,V.R. and Brown,P.O. (1997) Exploring the metabolic and genetic control of gene expression on a genomic scale. Science, 278, 680–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devreotes P.N. and Zigmond,S.H. (1988) Chemotaxis in eukaryotic cells: a focus on leukocytes and Dictyostelium. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol., 4, 649–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichinger L., Lee,S.S. and Schleicher,M. (1999) Dictyostelium as model system for studies of the actin cytoskeleton by molecular genetics. Microsc. Res. Tech., 47, 124–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M.J. et al. (2002) Genome sequence of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nature, 419, 498–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin A.C. et al. (2002) Functional organization of the yeast proteome by systematic analysis of protein complexes. Nature, 415, 141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge H., Liu,Z., Church,G.M. and Vidal,M. (2001) Correlation between transcriptome and interactome mapping data from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Genet., 29, 482–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner G., Szafranski,K., Winckler,T., Dingermann,T., Quail,M.A., Cox,E., Eichinger,L., Noegel,A.A. and Rosenthal,A. (2001) The complex repeats of Dictyostelium discoideum. Genome Res., 11, 585–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner G. et al. (2002) Sequence and analysis of chromosome 2 of Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature, 418, 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goff S.A. et al. (2002) A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science, 296, 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffeau A. et al. (1996) Life with 6000 genes. Science, 274, 546–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konfortov B.A., Cohen,H.M., Bankier,A.T. and Dear,P.H. (2000) A high-resolution HAPPY map of Dictyostelium discoideum chromosome 6. Genome Res., 10, 1737–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuspa A. and Loomis,W.F. (1996) Ordered yeast artificial chromosome clones representing the Dictyostelium discoideum genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 5562–5566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E.S. et al. (2001) Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature, 409, 860–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens H., Novotny,J., Oberstrass,J., Steck,T.L., Postlethwait,P. and Nellen,W. (2002) RNAi in Dictyostelium: the role of RNA-directed RNA polymerases and double-stranded RNase. Mol. Biol. Cell, 13, 445–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morio T. et al. (1998) The Dictyostelium developmental cDNA project: generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags from the first-finger stage of development. DNA Res., 5, 335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parent C.A. and Devreotes,P.N. (1996) Molecular genetics of signal transduction in Dictyostelium. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 65, 411–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivero F., Dislich,H., Glöckner,G. and Noegel,A.A. (2001) The Dictyostelium discoideum family of Rho-related proteins. Nucleic Acids Res., 29, 1068–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxe C.L. (1999) Learning from the slime mold: Dictyostelium and human disease. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 65, 25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skriwan C. et al. (2002) Various bacterial pathogens and symbionts infect the amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Int. J. Med. Microbiol., 291, 615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stechmann A. and Cavalier-Smith,T. (2002) Rooting the eukaryote tree by using a derived gene fusion. Science, 297, 89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Driessche N. et al. (2002) A transcriptional profile of multicellular development in Dictyostelium discoideum. Development, 129, 1543–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R.S., Cheng,L., Mudge,A.W. and Harwood,A.J. (2002) A common mechanism of action for three mood-stabilizing drugs. Nature, 417, 292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witke W., Schleicher,M. and Noegel,A.A. (1992) Redundancy in the microfilament system: abnormal development of Dictyostelium cells lacking two F-actin cross-linking proteins. Cell, 68, 53–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood V. et al. (2002) The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature, 415, 871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]