Abstract

Transcriptional activation from chromatin by nuclear receptors (NRs) requires multiple cofactors including CBP/p300, SWI/SNF and Mediator. How NRs recruit these multiple cofactors is not clear. Here we show that activation by androgen receptor and thyroid hormone receptor is associated with the promoter targeting of SRC family members, p300, SWI/SNF and the Mediator complex. We show that recruitment of SWI/SNF leads to chromatin remodeling with altered DNA topology, and that both SWI/SNF and p300 histone acetylase activity are required for hormone-dependent activation. Importantly, we show that both the SWI/SNF and Mediator complexes can be targeted to chromatin by p300, which itself is recruited through interaction with SRC coactivators. Furthermore, histone acetylation by CBP/p300 facilitates the recruitment of SWI/SNF and Mediator. Thus, our data indicate that multiple cofactors required for activation are not all recruited through their direct interactions with NRs and underscore a role of cofactor–cofactor interaction and histone modification in coordinating the recruitment of multiple cofactors.

Keywords: chromatin remodeling/cofactor recruitment/NRs

Introduction

Initiation of transcription in eukaryotic cells is a complicated multistep process involving a large number of cofactors that exert functions in remodeling of chromatin and/or recruitment of RNA polymerase II (Pol II) to the promoters of target genes (Lemon and Tjian, 2000). Because packaging of eukaryotic DNA into chromatin has a generally repressive effect on transcription, enzymes that alter chromatin structure have critical roles in the regulation of gene expression (Narlikar et al., 2002). The genomes of all eukaryotes studied code for a large number of chromatin remodeling and modification factors that are thought to evoke such changes (Jenuwein and Allis, 2001; Roth et al., 2001; Becker and Horz, 2002). Indeed, genetic and functional evidence places ATPase-containing complexes such as SWI/SNF or PBAF upstream of gene activation and repression (Fryer and Archer, 1998; Goldmark et al., 2000; Lemon et al., 2001). Further more, a large number of enzymes that generate a wide spectrum of covalent modifications on chromatin and non-histone regulators are also known to be required for processes as diverse as mating type loci silencing in yeast and transcriptional activation in mammals (Jenuwein and Allis, 2001; Turner, 2002). In all cases, however, the structural nature of the requirement for these chromatin modifying and remodeling activities in generating the transcriptionally active or repressed state in vivo remains a matter of much uncertainty and debate.

The nuclear receptors (NRs) form a large family of ligand-regulated transcription factors and play key roles in animal development, differentiation, homeostasis and tumorigenesis (Mangelsdorf et al., 1995). Transcriptional activation driven by liganded NRs has been associated with extensive chromatin structure alterations at target gene promoters and enhancers (Hager et al., 2000; Urnov and Wolffe, 2001; Kraus and Wong, 2002). Strong evidence illuminates the involvement of histone acetyltransferases (HATs) such as CBP/p300, ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes such as SWI/SNF or PBAF, and a complex (Mediator/TRAP/DRIP) that mediates communication with the basal transcriptional machinery in transcriptional activation by liganded NRs (Chakravarti et al., 1996; Fondell et al., 1996; Kamei et al., 1996; Rachez et al., 1998; Dilworth et al., 2000; Lemon et al., 2001). Whilst these activities are known to be targeted to NR-regulated promoters in vivo (Shang et al., 2000; Sharma and Fondell, 2002), the mechanisms by which NRs recruit multiple cofactor complexes remain poorly defined.

One possibility is that NRs recruit each cofactor complex through a direct NR–cofactor interaction. In support of this model, NRs have been reported to interact directly with the components of SWI/SNF (Ichinose et al., 1997; Nie et al., 2000; Belandia et al., 2002) and Mediator (Fondell et al., 1996; Rachez et al., 1998). Although CBP/p300 may interact directly with NRs, its participation in transcriptional activation by NRs is most likely mediated through interaction with SRC family coactivators (Li et al., 2000; Sheppard et al., 2001; Demarest et al., 2002). The SRC family consists of three highly related and possibly functionally redundant proteins that interact with NRs in a hormone-dependent manner and will be referred to herein under the unified nomenclature SRC-1, SRC-2 and SRC-3 (McKenna et al., 1999; Leo and Chen, 2000). Because SRC family coactivators, Mediator, and SWI/SNF all exist as large protein complexes and all appear to interact with a common binding site in the ligand-binding domain of the NRs, their association with a given NR molecule is thought to be mutually exclusive and is hypothesized to occur in a step-by-step, iterative manner (Ito and Roeder, 2001). Interestingly, the ‘order of recruitment’—if it exists—between the multitude of cofactors involved remains ill-defined, and appears to vary quite extensively between the very few cases where it has been studied in vivo (Cosma, 2002).

We present here a detailed in vivo analysis of molecular mechanisms by which well-studied representatives of both NR classes—the androgen receptor (AR; class I), and the thyroid hormone receptor (TR; class II)—induce activation in the context of chromatin. We show that hormone-dependent activation is associated with the specific recruitment of SRC family coactivators, p300, the SWI/SNF complex and the Mediator complex, to target gene promoters. We assay chromatin topology changes during activation to reveal the specific contribution that targeting of SWI/SNF makes to chromatin remodeling. We show that p300 has the capacity to mediate the recruitment of SWI/SNF as well as Mediator and that this recruitment is enhanced by histone acetylation exerted by CBP/p300. Our data suggest, therefore, that rather than proceed in a sequential manner by exchanging cofactors with NRs, all the remodeling, modification and Mediator complexes can be jointly recruited by the chromatin-bound NR via an adapter molecule (SRC) and that histone modification by one cofactor (p300) has a role in the recruitment of others (SWI/SNF and Mediator).

Results

Ligand-dependent activation by AR is associated with chromatin remodeling

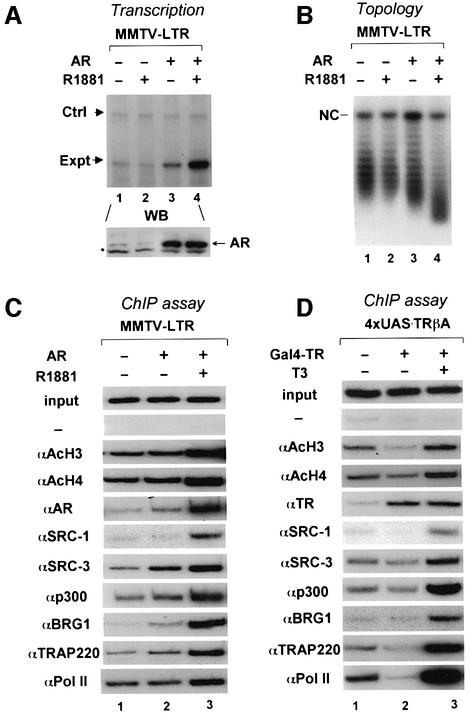

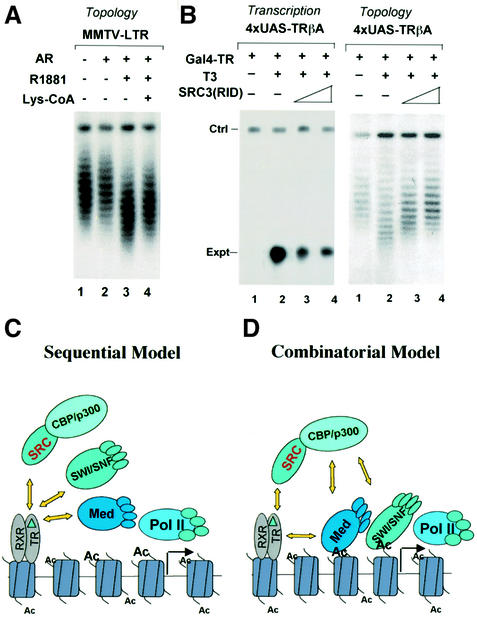

Previously we have demonstrated that hormone-dependent activation by TR is associated with alterations in chromatin that can be detected as loss of canonical nucleosomal ladder revealed by partial micrococcal nuclease digestion or loss of negative superhelical turns by a DNA topology assay (Wong et al., 1995, 1997). Recently we have reconstituted an agonist-responsive Xenopus oocyte transcription system for AR, a class I nuclear receptor, by assembling a MMTV-LTR-based reporter into chromatin via a replication-coupled pathway and expressing AR through microinjection of in vitro synthesized AR mRNA (Huang et al., 2002). This allowed us to test whether alteration of chromatin structure is also associated with AR activation. The result (Figure 1A) showed that addition of R1881, a synthetic AR agonist, not only stimulated transcription, but also resulted in an extensive loss of negative superhelical density (Figure 1B). A small change in topology also could be seen in the absence of R1881 (Figure 1B, compare lane 3 with 1), most likely as a consequence of hormone-independent activity by AR (Huang et al., 2002). The effect on DNA topology is not restricted to the MMTV-LTR reporter, as it was also observed when a different reporter was used (see Supplementary figure 1 available at The EMBO Journal Online). These experiments demonstrate that R1881-stimulated transcriptional activation is coupled with a chromatin remodeling event, as reported previously for TR (Wong et al., 1995, 1997).

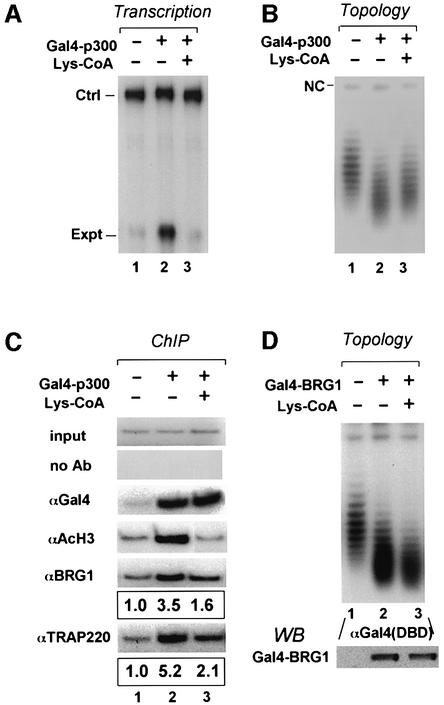

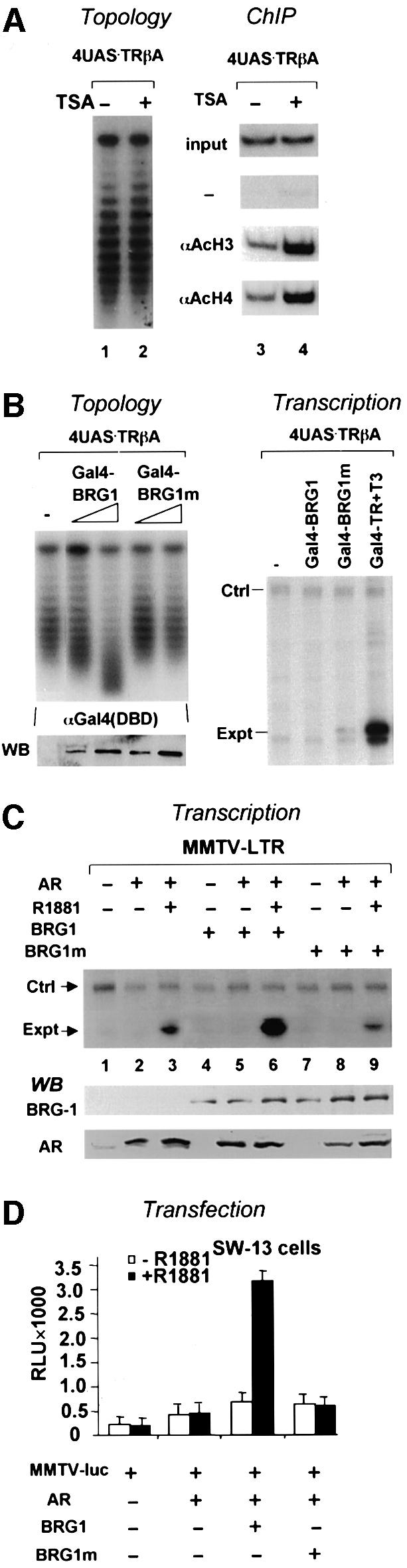

Fig. 1. Hormone-dependent activation by AR and TR is associated with chromatin remodeling with changes in DNA topology, histone acetylation and specific targeting of SRC-3, p300, BRG1 and TRAP220. (A) R1881-stimulated activation by AR from a MMTV-LTR reporter assembled into chromatin in Xenopus oocytes. The Ctrl represents the primer extension product from the oocyte storage histone H4 RNA. The expression of AR was detected by western blot using a FLAG-tag-specific antibody (M2; Sigma). (B) The same groups of oocytes as in (A) were analyzed for chromatin remodeling by a DNA topology assay. NC, nicked DNA. Faster migration in lane 4 in comparison with the control DNA indicates the loss of negative superhelical turns. (C) ChIP assays reveal histone acetylation and recruitment of different cofactors and RNA Pol II during R1881-stimulated activation by AR. The injection and treatment of oocytes were as in (A). Input DNA used for PCR was 5% of the total input DNA. Negative control (–) was performed without addition of antibody. (D) T3-dependent activation by TR is also associated with histone acetylation and promoter targeting of different cofactors and RNA Pol II. ChIP assays were performed with oocytes injected with 4×UAS.TRβA reporter and mRNA encoding Gal4–TR and treated with 50 nM T3 as described.

Hormone-dependent activation by AR and TR involves specific recruitment of both classes of chromatin remodeling factor and Mediator

We next wished to analyze the cofactors specifically recruited to the promoter region by AR during transcriptional activation using a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. In brief, Xenopus oocytes were injected with AR mRNA and MMTV-LTR reporter and treated or not with R1881, and after overnight incubation, the chromatin-associated proteins were crosslinked by incubation of the oocytes with formaldehyde, fragmented by sonication and specific antibodies as indicated were used to precipitate DNA crosslinked to the target proteins. PCR was performed to measure the amount of MMTV-LTR present in the immunoprecipitates. As shown in Figure 1C, R1881-stimulated activation is associated with the increased association of SRC-1, SRC-3, p300, BRG1 and TRAP220 and increased acetylation in histones H3 and H4. The increased association of BRG1, the ATPase subunit of the SWI/SNF complex and highly related PBAF complex (Lemon et al., 2001) (for simplicity, we refer to SWI/SNF and PBAF collectively as SWI/SNF), and TRAP220, a subunit of the metazoan Mediator, suggests that both SWI/SNF and the Mediator complexes were recruited by liganded AR. Finally, the association of Pol II, as revealed by using a Pol II large subunit-specific antibody, was also increased during hormone-dependent activation.

In parallel, we also tested whether those cofactors were recruited by TR during T3-dependent activation. For convenience, we carried out the experiments using a fusion protein containing the Gal4 DNA-binding domain (DBD) and the TR ligand-binding domain and a TRβA promoter-based reporter bearing four Gal4-binding sites (4×UAS.TRβA) (Li et al., 2002). Consistent with our previous results that unliganded TR repressed transcription as a result of specific recruitment of the HDAC3-containing SMRT/N–CoR complexes (Li et al., 2002), deacetylation of histone H3 and H4 was observed in the absence but not in the presence of T3. Under the condition where activation by TR was observed, ChIP assays revealed the increased association of cofactors SRC-1, SRC-3, p300, BRG1, TRAP220 and RNA Pol II as well. Although the results in Figure 1D were obtained with addition of T3 overnight, a time-course experiment (Supplementary figure 2) showed a similar result and revealed no significant fluctuation in cofactor recruitment. Taking these results together, we conclude that transcriptional activation by both AR and TR is correlated with the recruitment of SRC family members, p300, SWI/SNF and the Mediator complex.

The recruitment of SWI/SNF, but not histone acetylation, is responsible for chromatin remodeling with change in DNA topology

The above results indicate that hormone-dependent activation by AR and TR is associated with targeted histone acetylation (Figure 1C and D) and alteration of DNA topology (Figure 1B; see Wong et al., 1997). Whether these two events are interrelated is not clear. One possibility is that topology alteration during ligand-dependent activation is a consequence of chromatin acetylation. To test this possibility, we treated oocytes injected with the 4×UAS.TRβA reporter overnight with a potent HDAC inhibitor, trichostatin A (TSA). As expected, this treatment induced histone hyperacetylation as revealed by ChIP (Figure 2A). However, this marked hyperacetylation of chromatin did not lead to any measurable loss of superhelical density as compared with control chromatin (Figure 2A, compare lanes 1 and 2). These data exclude the possibility of histone acetylation as the sole cause of the DNA topology change observed during hormone-dependent activation.

Fig. 2. Targeting BRG1 to chromatin is sufficient for chromatin remodeling with changes in DNA topology, and a functional BRG1 is required for AR activation. (A) Histone acetylation is not the reason for changes in DNA topology. (B) Targeting of a wild type BRG1 but not an ATPase-deficient mutant to chromatin resulted in chromatin remodeling with change in topology. Groups of oocytes were injected with mRNA encoding Gal4–BRG1 or Gal4–BRG1m (K785R) and 4×UAS.TRβA reporter as indicated. After overnight incubation, the oocytes were used for analysis of DNA topology by supercoiling assay (left panel) and protein expression by western blot (bottom panel). The right panel shows that Gal4–BRG1 did not activate transcription in comparison with Gal4–TR in the presence of T3. (C) Expression of wild-type BRG1 but not the mutant stimulated AR activation in Xenopus oocytes. The expression of AR and wild-type or mutant BRG1 was detected by western analysis using a FLAG-specific antibody (M2, Sigma). (D) R1881-dependent activation by AR was impaired in SW13 cells and could be restored by co-transfection of BRG1. SW13 cells were transfected with a MMTV-LTR-driven luciferase reporter and AR or BRG1 expression construct as indicated. All experiments were carried out in triplicate and repeated twice; error bars represent the SEM.

Given the observed recruitment of BRG1 by liganded receptors (Figure 1C and D), the second possibility is that the observed topological change reflects chromatin remodeling by the SWI/SNF complex. To determine whether the SWI/SNF complex is responsible for the chromatin remodeling observed, we tested whether tethering to chromatin of the catalytic subunit of this complex, BGR1, which retains remodeling activity in vitro (Phelan et al., 1999), is sufficient to induce chromatin remodeling in vivo. We used a chromatinized reporter bearing four Gal4 DNA-binding sites, and found that expression of a Gal4–BRG1 fusion protein in Xenopus oocytes caused chromatin remodeling to an extent comparable to that seen during NR-driven activation (Figure 2B). This chromatin remodeling is dependent on the level of Gal4–BRG1 expression, and, importantly, the ATPase activity of BRG1, because under the same experimental conditions, expression of a Gal4–BRG1 fusion carrying a point mutation in its ATPase domain failed to do so (Figure 2B). This data indicate that tethering BRG1 to chromatin phenocopies the chromatin remodeling event observed during ligand-dependent activation by AR and TR. Of note, no transcriptional activation was observed for Gal4–BRG1 (Figure 2B, right panel), indicating that chromatin remodeling by BRG1 or SWI/SNF itself is insufficient for transcriptional activation. Importantly, this chromatin remodeling appears to be specific for BRG1, as tethering a closely related ATPase, ISWI, to chromatin via Gal4 failed to evoke any degree of chromatin remodeling at any level of fusion protein expression (Supplementary figure 3A).

A requirement for SWI/SNF and CBP/p300 HAT in ligand-dependent transcriptional activation

To evaluate the roles of chromatin remodeling instigated by SWI/SNF, we first tested whether expression of BRG1 could enhance AR activation. Indeed, expression of BRG1 in Xenopus oocytes markedly stimulated the activation by liganded AR, whereas the expression of BRG1 alone had no effect on transcription (Figure 2C). Again, the ability to enhance AR activation appears to be specific to BRG1, as expression of ISWI failed to do so (Supplementary figure 3C). Importantly, expression of the K785R BRG1 mutant not only failed to stimulate but inhibited AR activation. We take this result to suggest that the mutant BRG1 inhibits AR activation by competing with the endogenous SWI/SNF required for activation by AR.

To further evaluate the role of the SWI/SNF complex in AR activation, we utilized a BRG1/Brm-deficient cell line, SW13, that is known to impair the function of retinoic acid receptor (RAR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR) and estrogen receptor (ER) (Muchardt and Yaniv, 1993; DiRenzo et al., 2000). We found that transcriptional activation by AR was abrogated in SW13 cells, and that hormone-dependent activation could be rescued by introduction of an expression construct for wild-type BRG1 but not the remodeling-deficient K785R allelic version (Figure 2D). Thus, data both from Xenopus and mammalian cells provide strong evidence that BRG1 is required for hormone-dependent activation.

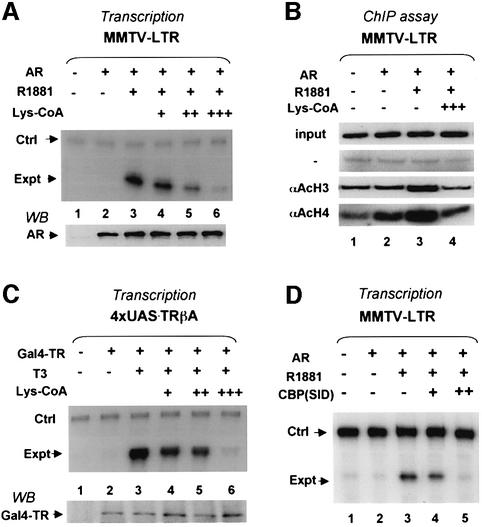

We next wished to determine the functional significance of histone acetylation in hormone-dependent transcriptional activation by AR and TR. As p300 was shown by ChIP assays to be recruited by both AR and TR, the observed histone acetylation most likely reflected the HAT activity of CBP/p300. We thus made use of a synthetic CBP/p300 selective HAT inhibitor, Lys-CoA, with an IC50 of ∼0.5 µM for CBP/p300 versus 200 µM for PCAF (Lau et al., 2000). The results (Figure 3A and C) showed that injection of this reagent inhibited both AR and TR activation in a dose-dependent manner. Given that the injection volume is <2% of the oocyte volume, the concentration of Lys-CoA in injected oocytes is expected to be diluted at least 50-fold, thus well below the concentration required for inhibition of PCAF activity. ChIP assays using acetylated H3- and H4-specific antibodies confirmed that at the concentration where the hormone-dependent activation was abrogated, targeted histone acetylation was also abolished (Figure 3B). We conclude that the HAT activity of CBP/p300 is essential for hormone-dependent activation by AR and TR. As the targeted histone acetylation is also inhibited, our results imply that targeted histone acetylation plays a critical role in hormone-dependent activation by AR and TR, although the possibility that inhibition of non-histone substrate acetylation may also contribute to the inhibition of transcription can not be excluded.

Fig. 3. Inhibition of CBP/p300 HAT activity or blocking SRC–CBP/p300 interaction abrogates hormone-dependent activation. (A) Endogenous CBP/p300 HAT activity is required for AR activation. The requirement of CBP/p300 HAT activity for AR activation was tested using a CBP/p300 selective HAT inhibitor, Lys-CoA. The oocytes were first injected with AR mRNA and then injected with ssDNA of the MMTV-LTR reporter (50 ng/µl, 18.4 nl/oocyte) containing 11.1 µM (+), 33.3 µM (++) or 100 µM (+++) of Lys-CoA. After overnight incubation with or without 50 nM R1881, the levels of transcription from the MMTV-LTR reporter were detected by primer extension assay and the level of AR protein is shown at the bottom panel by western blot. (B) ChIP assay revealed that Lys-CoA blocked hormone-dependent histone acetylation induced by AR. The groups of oocytes were injected with AR mRNA and ssDNA of the MMTV-LTR reporter with or without 100 µM of Lys-CoA as indicated. (C) Transcriptional activation by liganded TR also requires CBP/p300 HAT activity. (D) Expression of a CBP fragment (amino acids 2057–2170) containing the SRC interaction domain (SID) is sufficient to block AR activation.

SWI/SNF, p300 and the Mediator complex can be recruited to the NR via SRC family coactivators

Given the results (Figure 1C and D) that SRC coactivators, p300, SWI/SNF and Mediator are all targeted to promoter regions by liganded receptors, we next wished to examine how liganded receptors recruit these cofactors. The recruitment of CBP/p300, as shown previously (Li et al., 2000; Sheppard et al., 2001; Demarest et al., 2002), is most likely mediated through its interaction with SRC family coactivators. In support, expression of a fragment containing the SRC-interaction domain of CBP (amino acids 2057–2170) in Xenopus oocytes effectively blocked transcriptional activation by AR (Figure 3D). As human Mediator was initially isolated as liganded TR-associated proteins (Fondell et al., 1996), the recruitment of the Mediator complex can be explained as a ligand-dependent interaction between TRAP220 and receptors. However, despite numerous coimmunoprecipitation assays in mammalian cells or in Xenopus oocytes, we have yet to detect any ligand-dependent interaction between endogenous SWI/SNF or exogenously expressed BRG1 and either liganded TR or AR (data not shown).

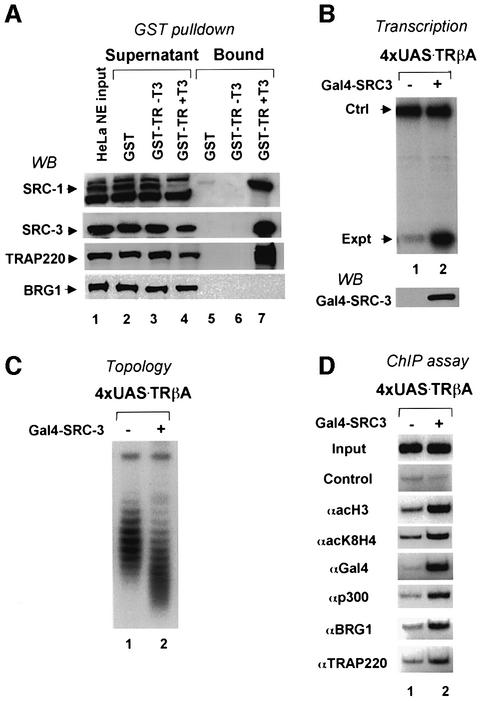

We next used a simple assay to determine whether the SWI/SNF complex, which is abundant in HeLa nuclear extract, could interact directly with liganded NRs. We incubated HeLa nuclear extracts with a GST–TR fusion protein in the absence and presence of T3, and the proteins bound to the GST–TR were isolated and analyzed by western blotting. Significant quantities of endogenous SRC coactivators and of the Mediator complex, but no detectable SWI/SNF, associated directly with the liganded receptor in this assay (Figure 4A), suggesting that the recruitment of BRG1 by liganded NRs (Figure 1C–D) is most likely indirect.

Fig. 4. The SWI/SNF complex is unlikely to be recruited directly by liganded TR but can be targeted to chromatin through a SRC family coactivator. (A) The interaction of SRC family coactivators, Mediator and SWI/SNF complex with TR was analyzed by GST–TR pulldown assay in vitro. Note that SRC-1, SRC-3 and TRAP220 were bound to GST–TR in a T3-dependent manner, whereas no interaction was observed between BRG1 and GST–TR. (B) Tethering SRC-3 to chromatin is sufficient for transcriptional activation. The oocytes were injected with or without mRNA encoding a Gal4–SRC-3 fusion protein (200 ng/µl, 18.4 nl/oocyte) and ssDNA of the 4×UAS.TRβA reporter. After overnight incubation, transcription was analyzed by primer extension in (B), DNA topology assay in (C) and ChIP assays in (D).

Given the prominent interaction of SRC family coactivators with liganded receptors, we hypothesized that the SWI/SNF complex could be recruited indirectly through SRC family coactivators. We tested this hypothesis by determining whether tethering a SRC family coactivator to chromatin is sufficient to recruit SWI/SNF and to induce chromatin remodeling. The result in Figure 4B showed that expression of Gal4–SRC-3 in Xenopus oocytes activated transcription from the injected 4×UAS.TRβA reporter. Furthermore, a DNA topology assay (Figure 4C) showed that the expression of Gal4–SRC-3 also resulted in chromatin remodeling.

To understand how tethering a SRC coactivator is sufficient for transcriptional activation and chromatin remodeling, we performed ChIP assays (Figure 4D) to examine the recruitment of various cofactors and histone acetylation. Consistent with its role in recruitment of p300, ChIP assay revealed specific recruitment of p300 by Gal4–SRC-3 as well as acetylation of histones H3 and H4. Importantly, recruitment of BRG1 was also observed, thus demonstrating that a SRC family coactivator is capable of recruiting SWI/SNF through a direct or indirect interaction.

Consistent with our data showing that tethering of SRC is sufficient for transcriptional activation (Figure 4B), we found that Gal4–SRC-3 also recruited TRAP220, indicating that the Mediator complex can be recruited by a SRC family coactivator. The ability to activate transcription and induce chromatin remodeling as well as the recruitment of p300, BRG1 and TRAP220 is not restricted to SRC-3, as the same results were observed when SRC-1 and SRC-2 were tested under the same conditions (data not shown). These results indicate that members of the SRC coactivator family can function as an intermediary between liganded NRs and complexes critical for transcriptional activation such as CBP/p300, SWI/SNF, and Mediator.

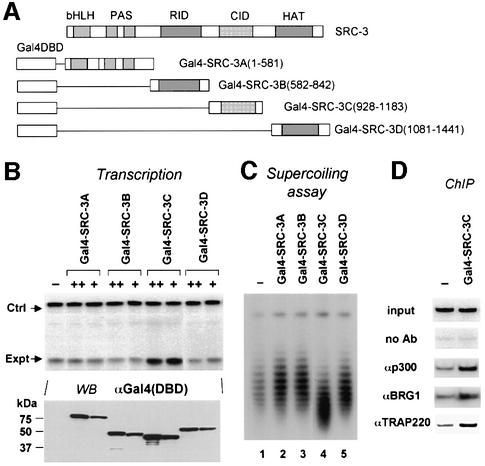

The recruitment of SWI/SNF and Mediator is likely mediated through CBP/p300

Having established that SRC family coactivators have the capacity to recruit SWI/SNF and the Mediator complex, we sought to determine which functional domain(s) in SRCs is required for this function. By using a series of SRC-3 constructs as shown in Figure 5A, we found that only the fusion protein containing the CBP/p300 interaction domain (CID) (Gal4–SRC-3C) significantly activated transcription from the 4×UAS.TRβA reporter (Figure 5B), whereas western analysis indicated that all fusion proteins were expressed at comparable levels (Figure 5B, lower panel). Furthermore, DNA topology assay indicated that only Gal4–SRC-3C induced a topological change (Figure 5C). Thus, both the transcriptional activation and chromatin remodeling functions of SRC-3 can be attributed to its CBP/p300 interaction domain. Indeed, side-by-side comparison of Gal4– SRC-3C and Gal4–SRC-3 revealed a similar capacity in transcriptional activation (Supplementary figure 4), suggesting that the CID represents the major, if not the entirety, of the autonomous activation activity of SRC-3.

Fig. 5. The ability of SRC-3 to induce transcriptional activation, chromatin remodeling and recruitment of SWI/SNF and Mediator is correlated with its interaction with CBP/p300. (A) Diagram of the different functional domains of SRC-3 fused to Gal4 DBD. bHLH/PAS, basic helix–loop–helix and PAS dimerization domain; NID, nuclear receptor interaction domain; CID, CBP/p300 interaction domain; HAT, histone acetyltransferase domain. (B) Only the fragment containing the CID is sufficient for transcriptional activation when tethering to chromatin. The concentrations of mRNA used: +, 100 ng/µl and ++, 300 ng/µl. The transcription was assayed by primer extension and the protein expression was revealed by western analysis using a Gal4 DBD-specific antibody. (C) Topology assay showed that only Gal3-SRC-3C is capable of inducing DNA topological change. The concentration of mRNA used for each fusion protein is 300 ng/µl. (D) ChIP assays show that p300, BRG1 and TRAP220 can be recruited by Gal4–SRC-3C.

To further understand the mechanism by which Gal4–SRC-3C activated transcription and induced chromatin remodeling, we carried out ChIP assays to verify the recruitment of p300, BRG1 and TRAP220. As shown in Figure 5D, expression of Gal4–SRC-3C indeed led to the recruitment of p300, BRG1 and TRAP220.

The above results indicate that the recruitment of SWI/SNF and the Mediator complex is most likely mediated through CBP/p300. To test this hypothesis, we tested transcription regulatory properties of a Gal4–p300 fusion protein. In full agreement with our expectation, expression of Gal4–p300 in Xenopus oocytes activated transcription from the reporter (Figure 6A) and induced chromatin remodeling (Figure 6B). Furthermore, ChIP assays confirmed the recruitment of BRG1 and TRAP220 by Gal4–p300 (Figure 6C). As expected, expression of Gal4– p300 also led to increased histone acetylation (Figure 6C, αacH3).

Fig. 6. SWI/SNF and Mediator complexes can be recruited by p300 and this recruitment is facilitated by histone acetylation. (A) Tethering of p300 to chromatin is sufficient for transcriptional activation and this activation can be inhibited by Lys-CoA. Oocytes were injected with Gal4–p300 mRNA (200 ng/µl) and ssDNA of the 4×UAS.TRβA reporter with or without addition of Lys-CoA and assayed for transcription after overnight incubation. (B) Injection was as in (A) but assayed for chromatin remodeling by DNA topology assay. Note that Lys-CoA partially inhibited loss of negative superhelical density. (C) ChIP assays revealed that SWI/SNF and Mediator can be recruited by Gal4–p300, and co-injection of Lys-CoA abolished histone acetylation and partially inhibited the recruitment of BRG1 and TRAP220. The results for BRG1 and TRAP220 were also analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR and the average values of three independent experiments are shown. (D) Lys-CoA has no effect on chromatin remodeling instigated by Gal4–BRG1.

Functional interplay between histone acetylation and chromatin remodeling by SWI/SNF

As the above result points to CBP/p300 as the molecule that mediates SWI/SNF and Mediator recruitment, we assessed the potential role of histone acetylation in recruitment of SWI/SNF and Mediator. As shown in Figure 6A, activation by Gal4–p300 was abolished when its HAT activity was inhibited by the presence of Lys-CoA. Under the same conditions, injection of Lys-CoA partially inhibited chromatin remodeling by SWI/SNF, as the loss of superhelical density was reduced (Figure 6B, compare lanes 3 and 2). Interestingly, ChIP assays revealed that, in the presence of Lys-CoA, the recruitment of TRAP220 and BRG1 was also partially reduced (Figure 6C). To assess whether Lys-CoA or histone acetylation had a direct effect on chromatin remodeling activity by SWI/SNF, we tested the effect of Lys-CoA on the chromatin remodeling induced by Gal4–BRG1. As shown in Figure 6D, the chromatin remodeling induced by Gal4–BRG1 was not affected by addition of Lys-CoA. This result suggests that histone acetylation enhances the recruitment (or stable association) of SWI/SNF during AR and TR activation, but histone acetylation itself is not required for BRG1- or SWI/SNF-induced chromatin remodeling.

Given the observation that recruitment of SWI/SNF by Gal4–p300 was partially dependent on histone acetylation (Figure 6C), we next wished to determine whether the chromatin remodeling induced by SWI/SNF during hormone-dependent activation is also partially dependent on histone acetylation. Indeed, the chromatin remodeling induced by liganded AR was partially inhibited by injection of the Lys-CoA inhibitor (Figure 7A). This result indicates that, as in the case of Gal4–p300, the recruitment of SWI/SNF by liganded AR is partially dependent on histone acetylation.

Fig. 7. Chromatin remodeling by liganded receptors is also partially dependent on histone acetylation, and blocking the recruitment of SRC coactivators inhibited chromatin remodeling. (A) Injection was similar to experiments in Figure 1A except that Lys-CoA (100 µM) was included as indicated. Note that Lys-CoA partially inhibited chromatin remodeling induced by liganded AR. (B) Expression of the RID of SRC-3 (amino acids 582–843) inhibited T3-dependent activation (left panel) and chromatin remodeling (right panel). (C) A sequential model showing that recruitment of SRC/p300, SWI/SNF and Mediator is achieved through independent interaction with liganded NRs. (D) A new combinatorial model showing that, in addition to NR–cofactor interaction, cofactor–cofactor and cofactor–histone interaction also contribute to the recruitment of multiple cofactors required for NR activation. CBP/p300 can mediate the recruitment of SWI/SNF and Mediator. Furthermore, histone acetylation by CBP/p300 facilitates subsequent recruitment of SWI/SNF and Mediator.

Blocking the recruitment of SRC coactivators inhibits chromatin remodeling induced by liganded receptors

The above results suggest a working model in which SWI/SNF is recruited by liganded receptors indirectly through the SRC/p300 cascade. A prediction of this model is that blocking the recruitment of SRC coactivators by liganded receptors would also block the recruitment of SWI/SNF. To our satisfaction, expression of the SRC-3 receptor interaction domain (amino acids 582–843) in Xenopus oocytes effectively blocked the DNA topological change instigated by SWI/SNF during activation by Gal4–TR (Figure 7B, right panel). As expected, this dominant-negative SRC-3 also inhibited T3-dependent transcription activation (Figure 7B, left panel).

Discussion

Chromatin remodeling by the SWI/SNF complex

Previous studies have correlated hormone-dependent transcriptional activation with chromatin remodeling, often revealed by loss of canonical nucleosomal ladder, formation of DNase I-hypersensitive sites, increased nuclease accessibility or changes in DNA topology. (Wong et al., 1995, 1997; Bhattacharyya et al., 1997; Fryer and Archer, 1998). Given the presence of multiple chromatin remodeling factors, it has been difficult to pinpoint the specific effect and function of a single factor. Here we provide compelling evidence that chromatin remodeling with change in DNA topology observed during hormone-dependent activation is instigated by the SWI/SNF complex targeted to chromatin by liganded receptors. First, as shown in Figure 2A, alteration in DNA topology is distinguishable from targeted histone acetylation and is not a consequence of histone acetylation. Secondly, as revealed by ChIP assays, BRG1, the ATPase subunit of the SWI/SNF complex, is recruited to the promoter regions by both liganded AR and TR. Thirdly, the chromatin remodeling with changes in DNA topology is recapitulated by tethering BRG1 but not the ISWI protein to chromatin (Figure 2B; Supplementary figure 3). These data are consistent with an in vitro study showing that only chromatin remodeling instigated by BRG1, but not by ISWI, is functionally coupled to changes in DNA topology (Aalfs et al., 2001). Finally, expression of BRG1 stimulates transcription activation in an ATPase-dependent manner (Figure 2C) and a functional BRG1 is required for hormone-dependent activation (Figure 2D). Collectively our data establish SWI/SNF as responsible for chromatin remodeling with change of DNA topology observed during the hormone-dependent activation process. Furthermore, as chromatin remodeling with changes in DNA topology is closely related to the loss of canonical nucleosomal ladder and formation of DNase I-hypersensitive sites (Wong et al., 1997), it is tempting to suggest that the latter two assays also reflect the chromatin remodeling instigated by SWI/SNF.

Requirement for HAT activity of both CBP/p300 and SWI/SNF complex for hormone-dependent activation

Through exogenous expression of CBP/p300 mutants defective in HAT activity, previous work indicates that the HAT activity of CBP/p300 is required for its ability to function as coactivator for most, but not all, NRs (Korzus et al., 1998; Kraus et al., 1999; Li et al., 2000). By using a CBP/p300 selective HAT inhibitor, Lys-CoA, we show that hormone-dependent activation by both AR and TR is critically dependent on endogenous CBP/p300 HAT activity. In addition, hormone-dependent activation by AR is also dependent on the function of SWI/SNF (Figure 2D), in agreement with results from other laboratories (Muchardt and Yaniv, 1993; Fryer and Archer, 1998; DiRenzo et al., 2000). These data collectively indicate that histone acetylation by CBP/p300 and the chromatin remodeling by SWI/SNF are both critically important for hormone-dependent activation by NRs.

Although it is not yet clear why hormone-dependent activation by NRs requires both histone acetylation by CBP/p300 and chromatin remodeling by SWI/SNF, it is clear that histone acetylation and chromatin remodeling by SWI/SNF have distinct effects on chromatin. Only chromatin remodeling by SWI/SNF leads to the change of DNA topology (Figure 2), whereas histone acetylation per se fails to do so (Figure 2A). It is generally believed that histone acetylation is likely to affect nucleosomal higher order structure, histone tail–DNA interactions and/or serve as a ‘code’ for docking of regulatory proteins (such as SWI/SNF) and the basal transcriptional machinery (Wolffe and Hayes, 1999; Jenuwein and Allis, 2001; Roth et al., 2001). In contrast, SWI/SNF can alter chromatin structure by inducing changes in conformation and/or position (sliding) and DNA topology, which is likely required for exposing important regulatory DNA sequences to transcription factors and especially basal transcription machinery (Kingston and Narlikar, 1999; Peterson and Workman, 2000; Becker and Horz, 2002). However, it should be noted that whether the requirement for both histone acetylation by CBP/p300 and chromatin remodeling by SWI/SNF is a general phenomenon for transcription activation from chromatin or is restricted to only a subset of genes such as targets for NRs is currently not known.

The roles of cofactor–cofactor interaction and histone modification in recruitment of CBP/p300, SWI/SNF and Mediator by liganded NRs

In addition to the NR–cofactor interaction identified previously, our study reveals a critical role of cofactor– cofactor interaction and histone modification in recruiting multiple cofactors whose concerted function is required for transcriptional activation by NRs. The role of SRC coactivators in recruiting CBP/p300 is well documented. Although previous studies suggest that NRs may recruit the SWI/SNF complex directly (Ichinose et al., 1997; DiRenzo et al., 2000; Nie et al., 2000; Belandia et al., 2002), our results indicate that SWI/SNF is unlikely to be recruited through a direct interaction with liganded TR (Figure 4A). Rather, on the basis of both functional and recruitment assays, we show that SWI/SNF can be recruited by NRs indirectly through p300, which itself is recruited through interaction with SRC coactivators (Figures 4–7). Further more, the recruitment of SWI/SNF is partially dependent on histone acetylation, as inhibition of histone acetylation by Lys-CoA partially inhibits the recruitment of SWI/SNF (Figure 6C). This result is consistent with the histone code hypothesis and the results that acetylated histones tails serve as docking sites for bromodomain-containing proteins. Our data are also consistent with recent in vitro and in vivo studies showing that histone acetylation stabilizes the recruitment of the SWI/SNF complex to chromatin and that H4 K8 acetylation serves for recruitment of SWI/SNF (Agalioti et al., 2002; Hassan et al., 2002). However, it should be noted that histone acetylation itself appears to be insufficient for recruitment of the SWI/SNF complex, since hyperacetylation induced by TSA treatment failed to induce a change in DNA topology (Figure 2A) or recruit SWI/SNF complex (data not shown). Rather, a direct or indirect interaction between p300 and SWI/SNF is essential and sufficient for targeting of SWI/SNF complex to promoter regions, because the recruitment of SWI/SNF by p300 is only partially inhibited under the condition where histone acetylation is abolished (Figure 6C). Thus, the recruitment of SWI/SNF is likely to be initiated through a direct or indirect interaction with CBP/p300, and histone acetylation exerted by CBP/p300 subsequently provide additional anchors to further stabilize the recruitment of SWI/SNF.

Numerous published data have clearly established a direct interaction between Mediator and NRs (Ito and Roeder, 2001; Baek et al., 2002). Our result that tethering SRCs or p300 to chromatin is sufficient for the recruitment of the Mediator complex (Figures 4–7) also reveals an alternative pathway for recruitment of Mediator. This NR-independent recruitment may provide an explanation of why hormone-dependent activation by NRs is impaired but not abolished in TRAP220–/– mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (Ito et al., 2000). Given the critical roles of the metazoan Mediator in both basal and activated transcription (Holstege et al., 1998; Baek et al., 2002), we suggest that the mild effect of TRAP220 deficiency on transcriptional activation by NRs could be explained by its indirect recruitment through CBP/p300. Interestingly, the recruitment of TRAP220 by p300 is also partially dependent on histone acetylation (Figure 6C), a result consistent with a recent study on the recruitment of Mediator complex to a TR-responsive gene in HeLa cells (Sharma and Fondell, 2002).

Together our data provide evidence for a new working model (Figure 7D) in which all cofactors essential for hormone-dependent activation by NRs can be recruited through a combinatorial effect of (direct or indirect) NR–cofactor, cofactor–cofactor and cofactor–histone interactions. In divergence from the sequential model in which different cofactors are all recruited through a direct interaction with liganded NRs (Figure 7C), in this new model, liganded NRs such as TR/RXR first interact with the members of SRC family coactivators, which in turn recruit CBP/p300. The recruitment of SWI/SNF is mediated through a direct or indirect interaction with CBP/p300 and is further stabilized by histone acetylation exerted by CBP/p300. The Mediator complex can be recruited either through a direct interaction with NRs or indirectly through CBP/p300, thus revealing a role of histone acetylation by one factor (p300) in recruitment of other essential cofactors (SWI/SNF and Mediator). However, we shall point out that the models in Figure 7C and D are not mutually exclusive and that SWI/SNF can be potentially recruited directly by other NRs such as GR and ER. Given the wide involvement of CBP/p300 in gene expression, our data that CBP/p300 can mediate the recruitment of SWI/SNF and Mediator is of general significance in understanding transcription regulation in higher eukaryotes.

Materials and methods

Plasmid constructs

The reporter plasmids 4×UAS.TRβA and MMTV-LTR–CAT were as described previously (Huang et al., 2002; Li et al., 2002), respectively. The single strand (ss) reporter plasmids were prepared from phagemids induced with helper phage VCS M13 as described previously (Wong et al., 1995). The constructs for in vitro synthesis of mRNAs encoding FLAG–SRC-1, FLAG–SRC-2, FLAG–SRC-3, p300, p300HATm, FLAG–AR and Gal4–TRβA were described previously (Li et al., 2000; Huang et al., 2002). The constructs for Gal4 fusions of SRCs, SRC-3 deletion mutants, BRG1 and BRG1(R785K), Xenopus ISWI and p300, respectively, were generated by inserting the corresponding cDNA fragments into the pSP64poly(A)-Gal4(DBD) vector.

In vitro synthesis of mRNAs and microinjection of Xenopus oocytes

The synthesis of mRNAs in vitro was carried out using DNA templates linearized with a suitable restriction enzyme and a SP6 Message Machine kit (Ambion, Inc.) as described by the manufacturer. The preparation of stage VI Xenopus oocytes and microinjection were essentially as described by Wong et al. (1995). Unless indicated in figure legends, ssDNA was injected (50 ng/µl, 18.4 nl/oocyte) into the nuclei of the oocytes, whereas the indicated amount of mRNAs encoding receptors or coactivators was injected into the cytoplasm of the oocytes (18.4 nl/oocyte). After overnight incubation with or without hormone, the oocytes were collected and divided into four groups for western analysis, transcription analysis by primer extension, DNA supercoiling assay and ChIP assays.

Supercoiling assay of chromatin structure, transcription analysis and western analysis

Analysis of DNA topology by supercoiling assay and transcription by primer extension were performed as described previously (Wong et al., 1997; Huang et al., 2002). The internal control was the primer extension product of the endogenous histone H4 mRNA using a H4-specific primer as described (Wong et al., 1997). The analysis of protein expression in Xenopus oocytes after injection of mRNAs was carried out by western analysis using a FLAG-tag-specific antibody (M2, Sigma) or a Gal4 DBD-specific antibody (RK5C1; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ChIP assays

ChIP assays with injected Xenopus oocytes were performed essentially as described (Li et al., 2002). The ChIP PCR for the MMTV-LTR construct generated a 150 bp PCR product, whereas the reaction for 4×UAS.TRβA construct generated a product of 100 bp. The antibodies against acetylated H3 (06-599) or H4 (06-598) were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology. The antibodies against human SRC-1 and SRC-3 were generated as described previously (Li et al., 2000) and recognized their Xenopus counterparts as well. The rabbit polyclonal antibody against Xenopus p300 was generated and affinity-purified against two synthetic peptides (amino acids 1033–1049 KSEPVELEEKKEEVKTE and amino acids 1487–1506 KPKRLQEWYKKMLDKSVSER). The BRG1 antibody was kindly provided by Dr Weidong Wang (NIA/NIH). The TRAP220 antibody was generated against a fragment of Xenopus TRAP220 (equivalent to human TRAP220 1351–1580).

Cell lines and transient transfection

The SW-13 adrenal carcinoma cell line was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Sigma) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Sigma). Transient transfection and luciferase assay were essentially as described (Huang et al., 2002).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at The EMBO Journal Online.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs Fyodor D.Urnov, Sharon Dent and members of the Wong laboratory for critical reading and comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to Weidong Wang for BRG1 antibody and Paul Wade for Xenopus ISWI cDNA. This work is supported by DK56324 from NIH and PC991505 from the Department of Defense Prostate Cancer Program to J.W.

References

- Aalfs J.D., Narlikar,G.J. and Kingston,R.E. (2001) Functional differences between the human ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling proteins BRG1 and SNF2H. J. Biol. Chem., 276, 34270–34278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agalioti T., Chen,G. and Thanos,D. (2002) Deciphering the transcriptional histone acetylation code for a human gene. Cell, 111, 381–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek H.J., Malik,S., Qin,J. and Roeder,R.G. (2002) Requirement of TRAP/mediator for both activator-independent and activator-dependent transcription in conjunction with TFIID-associated TAF(II)s. Mol. Cell. Biol., 22, 2842–2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker P.B. and Horz,W. (2002) ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 71, 247–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belandia B., Orford,R.L., Hurst,H.C. and Parker,M.G. (2002) Targeting of SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complexes to estrogen-responsive genes. EMBO J., 21, 4094–4103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya N., Dey,A., Minucci,S., Zimmer,A., John,S., Hager,G. and Ozato,K. (1997) Retinoid-induced chromatin structure alterations in the retinoic acid receptor β2 promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol., 17, 6481–6490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarti D., LaMorte,V.J., Nelson,M.C., Nakajima,T., Schulman,I.G., Juguilon,H., Montminy,M. and Evans,R.M. (1996) Role of CBP/p300 in nuclear receptor signalling. Nature, 383, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosma M.P. (2002) Ordered recruitment: gene-specific mechanism of transcription activation. Mol. Cell, 10, 227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarest S.J., Martinez-Yamout,M., Chung,J., Chen,H., Xu,W., Dyson,H.J., Evans,R.M. and Wright,P.E. (2002) Mutual synergistic folding in recruitment of CBP/p300 by p160 nuclear receptor coactivators. Nature, 415, 549–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth F.J., Fromental-Ramain,C., Yamamoto,K. and Chambon,P. (2000) ATP-driven chromatin remodeling activity and histone acetyltransferases act sequentially during transactivation by RAR/RXR in vitro. Mol. Cell, 6, 1049–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiRenzo J., Shang,Y., Phelan,M., Sif,S., Myers,M., Kingston,R. and Brown,M. (2000) BRG-1 is recruited to estrogen-responsive promoters and cooperates with factors involved in histone acetylation. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 7541–7549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fondell J.D., Ge,H. and Roeder,R.G. (1996) Ligand induction of a transcriptionally active thyroid hormone receptor coactivator complex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 8329–8333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer C.J. and Archer,T.K. (1998) Chromatin remodelling by the glucocorticoid receptor requires the BRG1 complex. Nature, 393, 88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldmark J.P., Fazzio,T.G., Estep,P.W., Church,G.M. and Tsukiyama,T. (2000) The Isw2 chromatin remodeling complex represses early meiotic genes upon recruitment by Ume6p. Cell, 103, 423–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager G.L., Fletcher,T.M., Xiao,N., Baumann,C.T., Muller,W.G. and McNally,J.G. (2000) Dynamics of gene targeting and chromatin remodelling by nuclear receptors. Biochem. Soc. Trans., 28, 405–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A.H., Prochasson,P., Neely,K.E., Galasinski,S.C., Chandy,M., Carrozza,M.J. and Workman,J.L. (2002) Function and selectivity of bromodomains in anchoring chromatin-modifying complexes to promoter nucleosomes. Cell, 111, 369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege F.C., Jennings,E.G., Wyrick,J.J., Lee,T.I., Hengartner,C.J., Green,M.R., Golub,T.R., Lander,E.S. and Young,R.A. (1998) Dissecting the regulatory circuitry of a eukaryotic genome. Cell, 95, 717–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z., Li,J. and Wong,J. (2002) AR possesses an intrinsic hormone-independent transcriptional activity. Mol. Endocrinol., 16, 924–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose H., Garnier,J.M., Chambon,P. and Losson,R. (1997) Ligand-dependent interaction between the estrogen receptor and the human homologues of SWI2/SNF2. Gene, 188, 95–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M. and Roeder,R.G. (2001) The TRAP/SMCC/Mediator complex and thyroid hormone receptor function. Trends Endocrinol. Metab., 12, 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M., Yuan,C.X., Okano,H.J., Darnell,R.B. and Roeder,R.G. (2000) Involvement of the TRAP220 component of the TRAP/SMCC coactivator complex in embryonic development and thyroid hormone action. Mol. Cell, 5, 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenuwein T. and Allis,C.D. (2001) Translating the histone code. Science, 293, 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamei Y. et al. (1996) A CBP integrator complex mediates transcriptional activation and AP-1 inhibition by nuclear receptors. Cell, 85, 403–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston R.E. and Narlikar,G.J. (1999) ATP-dependent remodeling and acetylation as regulators of chromatin fluidity. Genes Dev., 13, 2339–2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzus E., Torchia,J., Rose,D.W., Xu,L., Kurokawa,R., McInerney,E.M., Mullen,T.M., Glass,C.K. and Rosenfeld,M.G. (1998) Transcrip tion factor-specific requirements for coactivators and their acetyltransferase functions. Science, 279, 703–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus W.L. and Wong,J. (2002) Nuclear receptor-dependent transcription with chromatin. Is it all about enzymes? Eur. J. Biochem., 269, 2275–2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus W.L., Manning,E.T. and Kadonaga,J.T. (1999) Biochemical analysis of distinct activation functions in p300 that enhance transcription initiation with chromatin templates. Mol. Cell. Biol., 19, 8123–8135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau O.D. et al. (2000) HATs off: selective synthetic inhibitors of the histone acetyltransferases p300 and PCAF. Mol. Cell, 5, 589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon B. and Tjian,R. (2000) Orchestrated response: a symphony of transcription factors for gene control. Genes Dev., 14, 2551–2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon B., Inouye,C., King,D.S. and Tjian,R. (2001) Selectivity of chromatin-remodelling cofactors for ligand-activated transcription. Nature, 414, 924–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leo C. and Chen,J.D. (2000) The SRC family of nuclear receptor coactivators. Gene, 245, 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., O’Malley,B.W. and Wong,J. (2000) p300 requires its histone acetyltransferase activity and SRC-1 interaction domain to facilitate thyroid hormone receptor activation in chromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 2031–2042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Lin,Q., Wang,W., Wade,P. and Wong,J. (2002) Specific targeting and constitutive association of histone deacetylase complexes during transcriptional repression. Genes Dev., 16, 687–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangelsdorf D.J. et al. (1995) The nuclear receptor superfamily: the second decade. Cell, 83, 835–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna N.J., Xu,J., Nawaz,Z., Tsai,S.Y., Tsai,M.J. and O’Malley, B.W. (1999) Nuclear receptor coactivators: multiple enzymes, multiple complexes, multiple functions. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol., 69, 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchardt C. and Yaniv,M. (1993) A human homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae SNF2/SWI2 and Drosophila brm genes potentiates transcriptional activation by the glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO J., 12, 4279–4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar G.J., Fan,H.Y. and Kingston,R.E. (2002) Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell, 108, 475–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Z., Xue,Y., Yang,D., Zhou,S., Deroo,B.J., Archer,T.K. and Wang,W. (2000) A specificity and targeting subunit of a human SWI/SNF family-related chromatin-remodeling complex. Mol. Cell. Biol., 20, 8879–8888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C.L. and Workman,J.L. (2000) Promoter targeting and chromatin remodeling by the SWI/SNF complex. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 10, 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan M.L., Sif,S., Narlikar,G.J. and Kingston,R.E. (1999) Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol. Cell, 3, 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rachez C., Suldan,Z., Ward,J., Chang,C.P., Burakov,D., Erdjument-Bromage,H., Tempst,P. and Freedman,L.P. (1998) A novel protein complex that interacts with the vitamin D3 receptor in a ligand-dependent manner and enhances VDR transactivation in a cell-free system. Genes Dev., 12, 1787–1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S.Y., Denu,J.M. and Allis,C.D. (2001) Histone acetyltransferases. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 70, 81–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y., Hu,X., DiRenzo,J., Lazar,M.A. and Brown,M. (2000) Cofactor dynamics and sufficiency in estrogen receptor-regulated transcription. Cell, 103, 843–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma D. and Fondell,J.D. (2002) Ordered recruitment of histone acetyltransferases and the TRAP/Mediator complex to thyroid hormone-responsive promoters in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 99, 7934–7939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard H.M., Harries,J.C., Hussain,S., Bevan,C. and Heery,D.M. (2001) Analysis of the steroid receptor coactivator 1 (SRC1)–CREB binding protein interaction interface and its importance for the function of SRC1. Mol. Cell. Biol., 21, 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner B.M. (2002) Cellular memory and the histone code. Cell, 111, 285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urnov F.D. and Wolffe,A.P. (2001) A necessary good: nuclear hormone receptors and their chromatin templates. Mol. Endocrinol., 15, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolffe A.P. and Hayes,J.J. (1999) Chromatin disruption and modification. Nucleic Acids Res., 27, 711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J., Shi,Y.B. and Wolffe,A.P. (1995) A role for nucleosome assembly in both silencing and activation of the Xenopus TRβA gene by the thyroid hormone receptor. Genes Dev., 9, 2696–2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J., Shi,Y.B. and Wolffe,A.P. (1997) Determinants of chromatin disruption and transcriptional regulation instigated by the thyroid hormone receptor: hormone-regulated chromatin disruption is not sufficient for transcriptional activation. EMBO J., 16, 3158–3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]