Abstract

Remarkably little is known about the in vivo organization of membrane-associated prokaryotic DNA replication or the proteins involved. We have studied this fundamental process using the Bacillus subtilis phage φ29 as a model system. Previously, we demonstrated that the φ29-encoded dimeric integral membrane protein p16.7 binds to ssDNA and is involved in the organization of membrane-associated φ29 DNA replication. Here we demonstrate that p16.7 forms multimers, both in vitro and in vivo, and interacts with the φ29 terminal protein. In addition, we show that in vitro multimerization is enhanced in the presence of ssDNA and that the C-terminal region of p16.7 is required for multimerization but not for ssDNA binding or interaction with the terminal protein. Moreover, we provide evidence that the ability of p16.7 to form multimers is crucial for its ssDNA-binding mode. These and previous results indicate that p16.7 encompasses four distinct modules. An integrated model of the structural and functional domains of p16.7 in relation to the organization of in vivo φ29 DNA replication is presented.

Keywords: Bacillus subtilis/bacteriophage φ29/in vivo DNA replication/ssDNA binding/terminal protein interaction

Introduction

Eukaryotic DNA replication occurs at numerous fixed positions within the nucleus, as assessed by microscopic imaging techniques, implying that they are attached to subcellular structures (reviewed in Cook, 1999). During recent years, microscopic imaging tools have been developed for prokaryotic research and the results obtained have contributed importantly to a better understanding of in vivo prokaryotic DNA replication and related processes (Jensen and Shapiro, 2000). One of the most important recent contributions is the discovery that replicative DNA polymerase of Bacillus subtilis is located at relatively stationary cellular positions (Lemon and Grossman, 1998). This study had a vast impact on the view of prokaryotic DNA replication. First, it implied that the replicating DNA template moves through the stationary polymerase, contrary to the generally accepted view that the DNA polymerase moves along the DNA during replication. Second, it indicated that DNA polymerase, together with other proteins involved in DNA replication, are organized in so-called stationary replication factories. Finally, the stationary position of the replication factory entails that it is attached to a substructure. This adapted view of DNA replication, which most probably applies to all bacteria, shows remarkable similarities to that of eukaryotic DNA replication (reviewed in Cook, 1999), indicating that the basic principles of prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA replication are more conserved than was previously thought.

Compelling evidence has been provided during the past few decades that prokaryotic DNA replication, including that of resident plasmids and infecting phages, occurs at the cellular membrane (for review see Firshein, 1989), which most probably is the substructure to which prokaryotic replication factories are attached. The majority of functional studies on prokaryotic DNA replication and related processes, however, are in vitro studies using either purified soluble proteins or soluble cell extracts. Although these and the microscopic imaging studies have provided detailed insight into the function and cellular localization of many proteins involved in these processes (for review see Kornberg and Baker, 1992; Jensen and Shapiro, 2000), they have not offered much insight into the in vivo organization of membrane-associated DNA replication and the proteins involved in this process.

The B.subtilis bacteriophage φ29 is one of the best-studied phages (for recent review see Meijer et al., 2001a). For several reasons φ29 is an attractive system to study membrane-associated DNA replication. First, it encodes most, if not all, proteins required for replication of its genome. Secondly, detailed knowledge is available on in vitro φ29 DNA replication. Thirdly, processes other than DNA replication that are probably involved in DNA–membrane interactions, such as DNA segregation, do not apply to the φ29 life cycle.

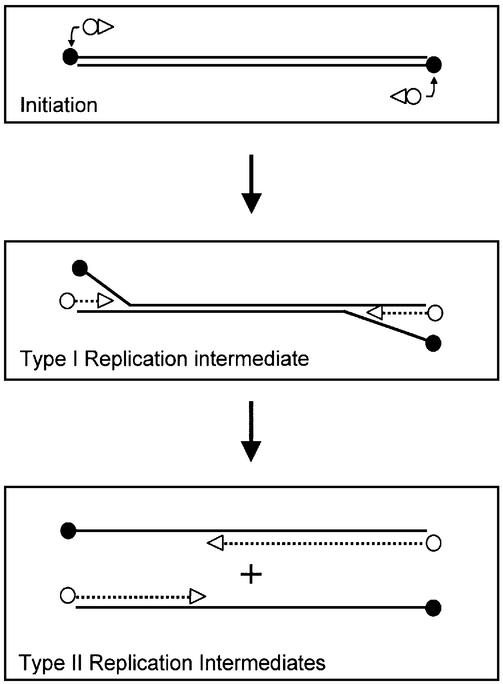

The genome of φ29 consists of a linear double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) of 19 285 bp that contains a terminal protein (TP) covalently linked at each 5′ end, which is called parental TP. Genes encoding proteins involved in phage DNA replication, such as the DNA polymerase, TP, single-stranded (ss) DNA-binding protein p5, dsDNA-binding protein p6 and protein p1 are clustered in an early-expressed operon. A schematic overview of the in vitro φ29 DNA replication mechanism is shown in Figure 1. Initiation of φ29 DNA replication occurs via a so-called protein-primed mechanism (reviewed in Salas, 1991; Salas et al., 1996; Meijer et al., 2001a). The parental TP-containing DNA ends constitute the origins of replication, which are recognized by a heterodimer formed by the φ29 DNA polymerase and TP (called primer TP). The DNA polymerase then catalyses the addition of the first dAMP to the primer TP. Next, after a transition step, these two proteins dissociate and the DNA polymerase continues processive elongation until replication of the nascent DNA strand is completed. Replication, which starts at both DNA ends, is coupled to strand displacement. This results in the generation of so-called type I replication intermediates consisting of full-length double-stranded φ29 DNA molecules with one or more ssDNA branches of varying lengths. When the two converging DNA polymerases merge, a type I replication intermediate becomes physically separated into two type II replication intermediates. Each of these consists of a full-length φ29 DNA molecule in which a portion of the DNA, starting from one end, is double-stranded and the portion spanning to the other end is single-stranded.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the in vitro φ29 DNA replication mechanism. See text for details. Black circles, white circles and triangles represent parental TP, primer TP and DNA polymerase, respectively. Synthesized DNA strands are indicated with broken lines. Adapted from Meijer et al. (2000).

Membrane-associated φ29 DNA replication was demonstrated for the first time by Ivarie and Pène (1973). In addition, these authors provided evidence that early-expressed φ29 proteins are required for membrane-associated φ29 DNA replication. Gene 16.7, present in a second early-expressed operon of φ29, is conserved in all φ29-related phages studied (Meijer et al., 2001a). Analyses of the deduced p16.7 protein sequence suggested that it would be an integral membrane protein. These features made p16.7 an attractive candidate to be involved in membrane-associated φ29 DNA replication. We demonstrated that p16.7 is an early-expressed integral membrane protein (Meijer et al., 2000, 2001b) and immuno-fluorescence studies indicated that it is involved in the organization of membrane-associated φ29 DNA replication (Meijer et al., 2000). Biochemical studies using a soluble variant lacking the N-terminal membrane anchor, p16.7A, revealed that p16.7A is a dimer in solution (Meijer et al., 2001b) and, importantly, that it has high affinity for DNA. Interestingly, the binding activity of p16.7A was found to be higher for ssDNA than for dsDNA (Serna-Rico et al., 2002).

The major outcomes of the present studies are the findings that (i) p16.7A can interact with the primer TP and (ii) that, in addition to dimers, p16.7A is able to form multimers, which are favoured in the presence of DNA. Moreover, we demonstrate that the C-terminal region of p16.7A is required for multimerization. The results presented here make protein p16.7 one of the best-characterized prokaryotic proteins involved in membrane-associated DNA replication. Based on these results, together with those obtained previously, we present a comprehensive model explaining the important function that p16.7 plays in the organization of in vivo φ29 DNA replication.

Results

Protein p16.7A forms multimers in addition to dimers, and multimerization is enhanced in the presence of DNA

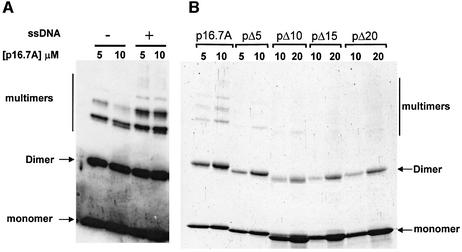

Glycerol gradient analysis showed that p16.7A forms dimers in solution (Meijer et al., 2001b). The region spanning amino acids 29–60 has a high potential to form an α-helical coiled-coil structure and is most probably responsible for p16.7A dimerization. In vitro crosslinking studies using purified p16.7A protein confirmed formation of p16.7A dimers (Meijer et al., 2001b). Interestingly, in addition to dimers, three additional crosslinked p16.7A species of higher molecular weight were detected in these experiments, indicating that p16.7A, besides dimers, can form multimers. Various experimental approaches showed that p16.7A has high ssDNA-binding capacity (Serna-Rico et al., 2002). To test the possibility that p16.7A multimerization might be favoured by ssDNA, in vitro p16.7A crosslinking assays were carried out in the absence or presence of ssDNA. The results, presented in Figure 2A, show that the intensity of the signals corresponding to the three crosslinked multimer species clearly increased when p16.7A was assayed in the presence of ssDNA. Moreover, faint additional signals migrating at positions indicating increased molecular weight were observed under these conditions. These results indicate that binding of p16.7A to ssDNA enhances or stabilizes the formation of p16.7A multimers. On the other hand, the intensity of the p16.7A multimer species decreased when crosslinking was performed in the presence of 250 mM NaCl, suggesting that the formation of p16.7A multimers is mediated by electrostatic interactions (results not shown). Figure 2B is explained below.

Fig. 2. Multimerization of p16.7A is enhanced in the presence of ssDNA (A) and requires its C-terminal region (B). The indicated amount of protein p16.7A or one of the C-terminally truncated proteins was incubated for 10 min at room temperature in the absence or presence of ssDNA (175 nt right-end φ29 DNA sequence) before being treated with DSS. Following crosslinking, the samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE. In (A), p16.7A species were detected by western blotting using polyclonal antibodies against p16.7. In (B), the protomer species were detected by staining the polyacrylamide gel with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, since the truncated proteins were hardly detected by the polyclonal antibodies against p16.7. The positions of p16.7A monomer, dimer and multimers are indicated.

To analyse whether native p16.7 forms dimers and multimers within the infected cell, in vivo crosslinking experiments were carried out (see Materials and methods). Whereas p16.7 was detected as a monomer without disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) treatment, an additional p16.7-specific signal, having an apparent molecular weight twice that of the p16.7 monomer, was detected at low DSS concentration. Various additional p16.7-specific signals corresponding to complexes of higher molecular weight were detected at more elevated DSS concentrations (results not shown). Taking into account the in vitro p16.7A crosslinking results described above it is most likely that native p16.7 forms dimers and multimers in vivo although it cannot be excluded that (some of) the signals obtained reflect p16.7 molecules crosslinked to other protein(s).

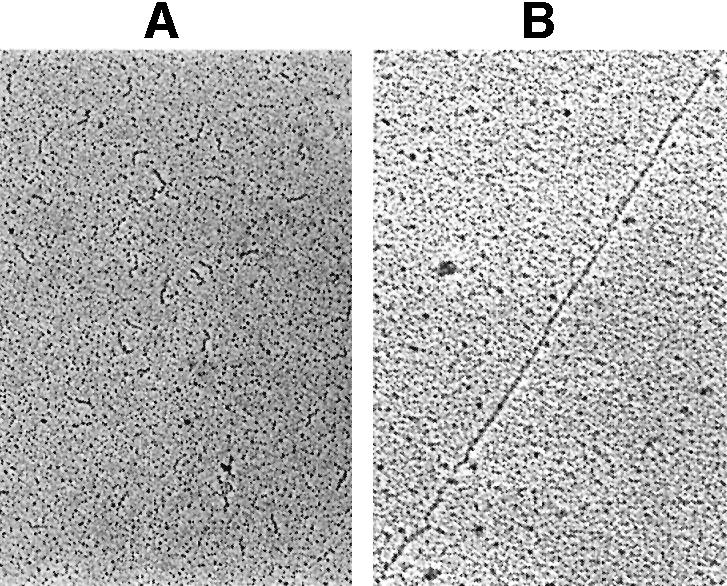

Protein p16.7A can join individual ssDNA fragments forming long nucleoprotein filaments in vitro

Among other techniques, gel retardation assays have been used to demonstrate that protein p16.7A has high affinity for ssDNA. Curiously, the nucleoprotein complexes formed at low ionic strength hardly entered native acrylamide gels at elevated p16.7A concentrations (Serna-Rico et al., 2002; see also Figure 4). To gain insight into the nature of the apparent high molecular weight nucleoprotein complexes formed by p16.7A these were analysed by electron microscopy. The minimal size of ssDNA fragments to be detected by this method is ∼300 nt, and, therefore, an ssDNA fragment of this size corresponding to the right end of the φ29 genome was used. Similar p16.7A:ssDNA ratios to those used in gel mobility assays were employed after which the samples were processed as described in Materials and methods. Interestingly, extremely long ssDNA filaments were observed in samples containing p16.7A but not in control samples prepared without p16.7A (compare Figure 3A and B). The filaments showed remarkable continuous and homogeneous structures without any indication of protein clusters, suggesting the lack of higher-order structures upon complex formation. These results indicate that protein p16.7A can join small ssDNA fragments resulting in filaments of high molecular weight. Protein p16.7A also binds dsDNA (Serna-Rico et al., 2002), although with lower affinity. Electron microscopic analyses showed that p16.7A can also join small dsDNA fragments forming large filaments of continuous and homogeneous structure (results not shown).

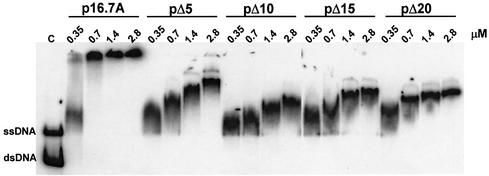

Fig. 4. Deletion of the C-terminal region of protein p16.7 affects the mode of ssDNA binding. The ssDNA-binding activity of pΔ5, pΔ10, pΔ15 and pΔ20 was analysed by gel retardation assay. Protein p16.7A was included as internal control. The 175 bp φ29 right-end fragment was labelled at its 5′ end, heat denatured and incubated with the indicated amounts of protein in a low ionic strength buffer. After non-denaturing PAGE, the mobility of the nucleoprotein complexes was detected by autoradiography. The positions of free dsDNA and ssDNA are indicated. C, control lane with premixed free dsDNA and ssDNA.

Fig. 3. Visualization by electron microscopy of high molecular weight p16.7A–ssDNA nucleoprotein complexes. The 300 bp φ29 right-end DNA fragment was heat denatured and processed in the absence (A) or presence (B) of 2 µg of p16.7A as described in Materials and methods, and subsequently analysed by electron microscopy. Representative images are shown. The order of magnification is 5000-fold.

The p16.7A C-terminal region is not required for dimerization or ssDNA binding but is essential for multimerization and filament formation

The observation that p16.7A multimerization is affected at high salt concentration indicated that it depends on electrostatic interactions. Analysis of the deduced p16.7A protein sequence shows that the 20 amino acid C-terminal region is highly charged (it contains six positively charged and one negatively charged residues), which may suggest that this region, being highly conserved in all p16.7 homologues known (Meijer et al., 2001a), is involved in protein multimerization. To test this hypothesis we constructed four mutants in which the last 5, 10, 15 or 20 codons of gene 16.7A were deleted. The corresponding mutant proteins, named pΔ5, pΔ10, pΔ15 and pΔ20, were purified and analysed. First, the ability of these truncated proteins to form dimers was studied. Glycerol gradient analyses, performed in the presence of 250 mM NaCl, established that the four mutant proteins are dimers in solution (results not shown), demonstrating that the C-terminal region is not required for p16.7A dimerization.

Next, the four mutant proteins were subjected to in vitro crosslinking in the presence of 50 mM NaCl. Protein p16.7A was included in the experiment to serve as internal reference. The detection of crosslinked dimer species of each of the four C-terminally truncated proteins (Figure 2B) is in agreement with their dimeric state in solution. Interestingly, the amounts of crosslinked multimer species were much lower with pΔ5 than with p16.7A, and were not or hardly detected in the case of the other three mutant proteins. These results strongly suggest that the C-terminal 10 amino acids of p16.7A are required for multimerization.

To study whether the C-terminal region of 16.7A is involved in ssDNA binding, the truncated proteins were analysed in gel mobility shift assays. The results, presented in Figure 4, show that all four mutant proteins retained ssDNA-binding activity. As expected under these conditions, the nucleoprotein complexes formed in the presence of p16.7A concentrations of ≥0.7 µM did not enter the gel. Interestingly however, although progressive retardation of the ssDNA probe was observed at increasing amounts of any of the four C-terminally truncated mutant proteins, the nucleoprotein complexes entered the gel at the protein concentrations tested. In the case of pΔ5 only, minor amounts of high molecular weight nucleoprotein complexes that did not enter the gel were formed at the highest protein concentration tested.

Next, the nucleoprotein complexes formed by the four p16.7A mutant proteins were analysed, along with p16.7A, by electron microscopy. Protein concentrations as high as 50 µM were tested. Whereas extremely long nucleoprotein filaments similar to those presented in Figure 3B were observed with p16.7A, no filaments were observed in samples prepared with any of the concentrations of pΔ10, pΔ15 or pΔ20 tested. Some nucleoprotein filaments were observed with pΔ5 at high protein concentrations. However, compared with those formed with p16.7A, they were observed in far lesser amount and with shorter mean size (results not shown). Together, these results show (i) that the C-terminal region of protein p16.7A is required for protein multimerization but not for ssDNA binding, and (ii) that the formation of long nucleoprotein filaments depends on p16.7A multimerization.

Micrococcal nuclease digestion analyses of nucleoprotein complexes formed by p16.7A or the C-terminal deletion derivatives

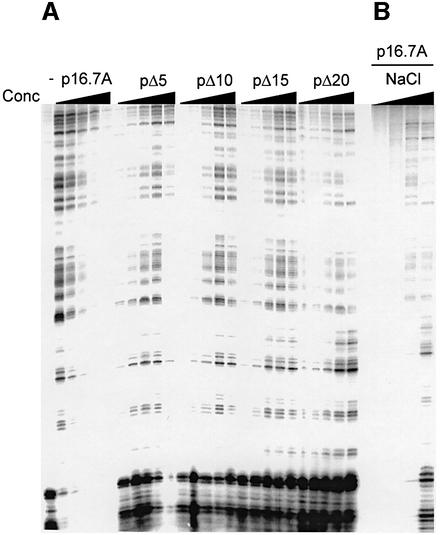

Binding to ssDNA was also studied by micrococcal nuclease digestion. This assay not only provides information on the mode of ssDNA binding, it also has the advantage over gel retardation studies that the nucleoprotein complexes are not subjected to electrophoresis. The binding conditions used in the micrococcal nuclease assays were chosen to be similar to those used in gel mobility shift assays (see Materials and methods). Thus, increasing amounts of p16.7A or each of the C-terminal deletion mutant proteins were incubated with 5′-labelled ssDNA probe. Next, the nucleoprotein complexes were challenged by micrococcal nuclease digestion, after which the DNA fragments were fractionated through denaturing polyacrylamide gels (see Figure 5A). In the absence of protein, nearly all the end-labelled fragment was degraded into small oligonucleotides. In the presence of 2.6 µM p16.7A, however, small oligonucleotides were hardly detected. Instead, a range of ssDNA digestion products of different sizes was generated, indicating that p16.7A partially protected the ssDNA from degradation. The resulting digestion pattern is the consequence of preferential cleavage by micrococcal nuclease at AT-rich regions (Flick et al., 1986). The level of degradation decreased at higher p16.7A concentrations resulting in (almost) complete protection at a concentration of 20.8 µM. The absence of digestion products at higher p16.7A concentrations strongly suggests that the nucleoprotein complex formed under these conditions consists of a continuous array of protein covering the entire DNA fragment. Comparison of the micrococcal nuclease ssDNA digestion patterns obtained with the C-terminal deletion derivatives with those obtained in the presence of p16.7A provided the following information. In the case of pΔ5, an ∼4-fold higher protein concentration was required to observe comparable levels of protection against nuclease degradation. Although partial protection of the ssDNA fragment was also observed in the presence of proteins pΔ10, pΔ15 or pΔ20, large amounts of small degradation products, especially in the case of protein pΔ20, were observed even in the presence of the highest protein concentration tested. This suggests that these proteins are unable to form continuous protein arrays.

Fig. 5. Micrococcal nuclease treatment of nucleoprotein complexes formed by p16.7A or C-terminally truncated proteins. The 300 bp right-end φ29 DNA fragment was end-labelled, heat-denatured and used in micrococcal nuclease digestion assays. The labelled ssDNA probe was preincubated either in the absence or presence of increasing amounts (2.6, 5.2, 10.4, 20.8 and 41.6 µM) of the indicated protein in a buffer containing 50 mM NaCl (A), or using a fixed amount of protein p16.7A (20.8 µM) in the presence of increasing salt concentrations (50, 100, 150 or 200 mM NaCl) (B). After complex formation, samples were treated with 0.5 mU of micrococcal nuclease for 10 min at 4°C, and the DNA products fractionated through polyacrylamide gels under denaturing conditions. Digestion of the ssDNA fragment without protein during a shorter period of time or using lower micrococcal nuclease concentrations gave patterns highly similar to those obtained in the presence of limited amounts of p16.7A. Control experiments showed that the nuclease activity was not inhibited by the increased salt concentrations.

Micrococcal nuclease assays were also used to study the effect of ionic strength on p16.7A binding to ssDNA. Figure 5B shows that, at a fixed p16.7A concentration of 20.8 µM, full protection was lost at increasing NaCl concentrations. Instead, partial protection patterns were obtained similar to those observed at low salt concentration with the C-terminally truncated proteins at the same protein concentrations or to those using much lower p16.7A concentrations. It thus appears that p16.7A is unable to form continuous arrays on ssDNA at high ionic strength, probably because p16.7A multimerization is affected.

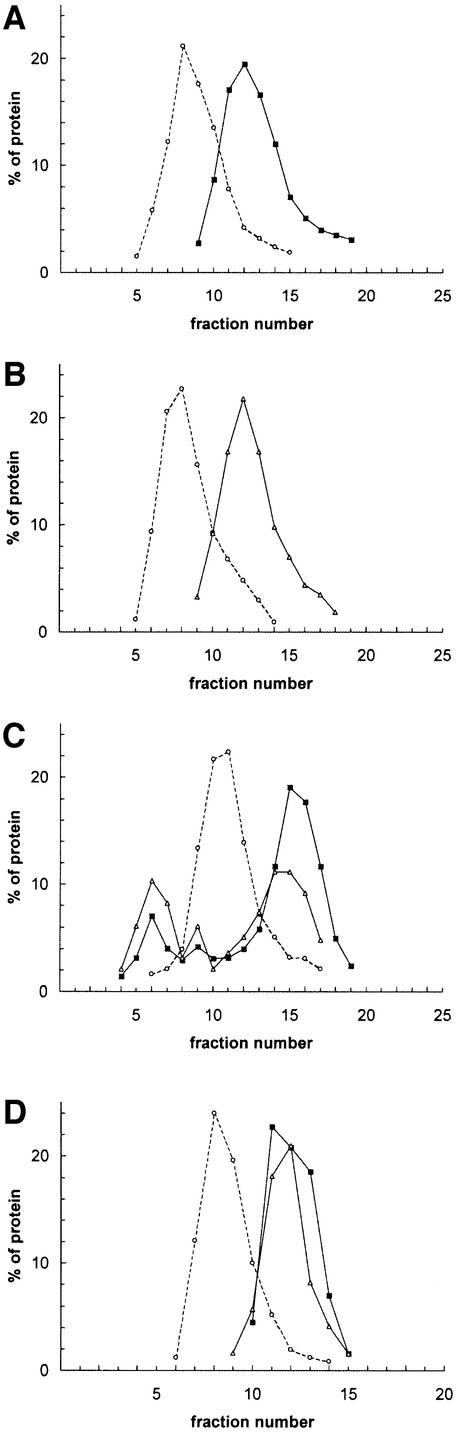

Protein p16.7A interacts with the terminal protein

The φ29 DNA replication intermediates contain long stretches of displaced ssDNA as a consequence of its protein-primed mechanism of replication (see Figure 1B). Because the displaced ssDNA strands contain a TP molecule covalently attached to their 5′ ends it was of interest to study whether protein p16.7A could interact with TP. As a first approach this possibility was studied by glycerol gradient analysis containing 50 mM NaCl. When analysed in separate gradients, protein p16.7A (14.5 kDa; Figure 6A) and TP (31 kDa; Figure 6B) were recovered as single peaks corresponding to their dimeric and monomeric states, respectively, in solution. Interestingly, when both proteins were preincubated before being analysed by ultracentrifugation (Figure 6C), part of p16.7A and TP cosedimented as two additional peaks (fractions four to ten) corresponding to approximate positions of 65 and 95 kDa. Taking into account the molecular weight of a p16.7A dimer (29 kDa) and a TP monomer (31 kDa) the ∼65 kDa peak fractions would consist of p16.7A dimer–TP monomer complexes. Considering the amounts of TP monomers and p16.7A dimers present in the ∼95 kDa peak (∼32 and 18% of the total, respectively) this peak would contain complexes consisting of one p16.7A dimer interacting with two TP monomers. Preincubated protein p16.7A and TP were also analysed in a gradient containing 500 mM NaCl (Figure 6D). Under these conditions, p16.7A and TP migrated as single protein peaks in the gradient corresponding to their dimeric and monomeric states, respectively. These latter data suggest that the p16.7A/TP interaction is mediated via electrostatic interactions. The high salt concentration does not affect dimerization of p16.7A, most probably because dimerization is based on hydrophobic interactions involving the putative coiled-coil region (Meijer et al., 2001b).

Fig. 6. Protein p16.7A interacts with the TP as assessed by glycerol gradient analysis. Protein p16.7A (12 µg) and TP (6 µg) were loaded separately (A and B, respectively) or together (C and D) on to glycerol gradients containing either 50 (A–C) or 500 mM NaCl (D). After centrifugation, the gradients were fractionated from the bottom and aliquots of each fraction were subjected to SDS–PAGE. The distribution of each protein in the gradient was determined by densitometric scanning of the stained gel and is represented graphically. BSA (66 kDa), which is a monomer in solution, was loaded on each gradient to serve as molecular weight marker. Circles, BSA; squares, p16.7A; triangles, TP.

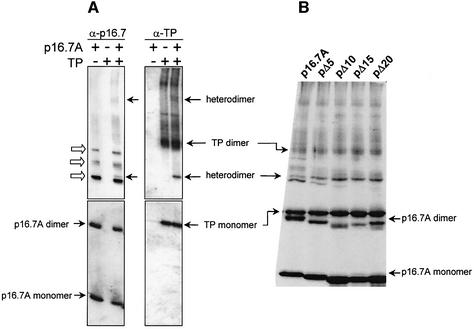

Additional support for the view that p16.7A interacts with TP was obtained by in vitro DSS crosslinking experiments. The crosslinked samples were subjected to SDS–PAGE and western blot analysis using polyclonal antibodies against p16.7 (see Figure 7A, left part). In agreement with the results presented above (see Figure 2) and those obtained previously (Meijer et al., 2001b), DSS treatment of purified p16.7A resulted in the formation of dimers and some multimers. In addition, a specific crosslinked product with the mobility expected for a p16.7A–TP complex was detected only when the reaction mixture contained both proteins. This specific crosslinked product was also detected when the western blot was stripped and re-used with antibodies against TP (Figure 7A, right part), demonstrating that the complex contained both p16.7A and TP. An additional diffuse band with an apparent molecular weight of ∼110 kDa was detected with both antibodies in the crosslinked sample containing both proteins, which could be compatible with the ∼95 kDa p16.7A–TP peak observed in glycerol gradients (Figure 6C).

Fig. 7. Protein p16.7A and its C-terminal deletion derivatives interact with the TP as assessed by in vitro crosslinking. (A) Protein p16.7A (12 µg) and TP (6 µg) were treated separately or together with DSS. For a better resolution, the proteins were separated on a 25 cm long SDS–polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was divided into two parts (upper and lower), transferred to PVDF membranes, western blotted using polyclonal antibodies against p16.7A, and revealed by chemiluminescence (left part). After stripping, the membranes were probed with antibodies against TP and revealed as indicated above (right part). (B) Proteins p16.7A, pΔ5, pΔ10, pΔ15 and pΔ20 were preincubated with TP, treated with DSS and subjected to SDS–PAGE. Next, the proteins were visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. The monomer position of TP and p16.7A, as well as the crosslinked heterodimer complexes, are indicated with filled arrows. Open arrows in (A) indicate crosslinked p16.7A multimers. Monomers and dimers of the truncated p16.7A protein are not indicated but migrate slightly below that of the corresponding migration positions of p16.7A. Control experiments showed that protein p16.7A did not become crosslinked to several other purified proteins such as BSA, or the φ29-encoded protein p4 or p5.

Initiation of φ29 DNA replication starts with the recognition of the origins of replication, i.e. the TP-containing DNA ends, by a TP/DNA polymerase heterodimer (Blanco et al., 1987). To study whether p16.7A can also interact with TP present in the TP/DNA polymerase heterodimer, p16.7A was incubated with preformed TP/DNA polymerase heterodimers and subsequently subjected to crosslinking. No p16.7A–TP complex was detected under these conditions (results not shown) suggesting that p16.7A does not interact with TP when the latter forms a heterodimer with the DNA polymerase.

To study whether the C-terminal region of p16.7A is required for interaction with TP, the p16.7A mutant proteins pΔ5, pΔ10, pΔ15 and pΔ20 were used in crosslinking experiments. In each case, a specific band with the apparent molecular weight expected for a crosslinked complex of TP with the corresponding p16.7A derivative was obtained when the reaction mixtures contained both proteins (Figure 7B), demonstrating that the C-terminal region of p16.7A is not required for interaction with TP.

Discussion

A major finding of this study is that protein p16.7A, involved in the organization of membrane-associated φ29 DNA replication (Meijer et al., 2000), interacts with the TP. This interaction may engage different functions. It may facilitate binding to the TP-containing ssDNA portions of the φ29 DNA replication intermediates. Alternatively, by binding to the TP/DNA polymerase heterodimer, p16.7 might recruit the latter either to the membrane or, since p16.7A also has DNA-binding activity, to the origin of replication. Based on analogy with the adenovirus DNA replication system, the latter possibility was attractive. Like φ29, the adenovirus genome consists of a linear dsDNA with a TP molecule attached at both 5′ ends and replicates its DNA via the protein-primed mechanism (for review see Salas et al., 1996). In the case of adenovirus serotype 2/5 (Ad 2/5) the TP/DNA polymerase heterodimer is recruited to the origins of replication by two host-encoded transcription factors, NFI and Oct-1 (reviewed in de Jong and van der Vliet, 1999). Whereas NFI has affinity for the DNA polymerase, Oct-1 binds to TP. In addition, each transcription factor binds to cognate recognition sites, which are located close to the origins of replication. To exert its role in recruitment, the Oct-1 protein was demonstrated to interact not only with free TP but also with the TP present in the TP–DNA polymerase complex (Coenjaerts et al., 1994). In the φ29 system, however, no evidence was obtained that p16.7A can interact with the TP when it is complexed with the DNA polymerase. On the one hand, no p16.7A–TP crosslinked species were observed when p16.7A was used in crosslinking reactions containing preformed TP/DNA polymerase heterodimers. On the other hand, the presence of excess amounts of p16.7A did not interfere with the in vitro φ29 DNA replication initiation reaction (Serna-Rico et al., 2002). Moreover, functional assays have provided evidence that the TP/DNA polymerase complex is recruited to the origin of replication via direct interactions between the parental TP and both the primer TP (Serna-Rico et al., 2000) and DNA polymerase (González-Huici et al., 2000) of the heterodimer. Together, these results make it unlikely that p16.7 would recruit the TP/DNA polymerase heterodimer to the origin of replication.

Most likely, the interaction of p16.7A with TP would facilitate binding to the TP-containing ssDNA portions of the φ29 DNA replication intermediates. During φ29 DNA replication the TP-containing φ29 DNA ends are the first regions to become displaced, and binding of p16.7 to both the TP and ssDNA would ensure rapid and selective recruitment of the φ29 DNA replication intermediates to appropriate sites at the membrane.

Another important finding of this work is that p16.7A dimers are able to form multimers. The amount of crosslinked p16.7A multimers increased significantly in the presence of ssDNA, indicating that ssDNA enhances or stabilizes p16.7A multimers, probably because p16.7A dimers become organized in a specific manner upon ssDNA binding favouring interdimeric p16.7A interactions. In fact, the results obtained indicate that p16.7A, when present in sufficient amounts, binds ssDNA in a continuous array. This conclusion is based on the following observations. First, p16.7A can fully protect ssDNA fragments against micrococcal nuclease digestion and second, microscopic analysis of p16.7A–ssDNA complexes revealed remarkable homogeneous and continuous structures without any indication of protein clusters. This situation is different from that observed with some ssDNA-binding proteins, which can organize ssDNA in ‘nucleosome-like units’, such as the SSB of Escherichia coli (Chrysogelos and Griffith, 1982) and the RPA SSB of yeast (Alani et al., 1992). Electron microscopic analysis of the latter nucleoprotein complexes show typical ‘beads on a string’-like structures and limited digestion of these structures with micrococcal nuclease resulted in repeating patterns of protected and unprotected ssDNA sequences.

Crosslinking analyses demonstrated that the C-terminal region of p16.7A is required for multimerization. The C-terminally truncated proteins retained their ability to form dimers and to interact with TP, indicating that the overall protein structure is not lost in these mutant proteins. Further support for this assumption is that they retained ssDNA-binding activity. However, their ssDNA-binding properties were different from those of p16.7A. Thus, mutant proteins pΔ10, pΔ15 and pΔ20 were unable to join separate ssDNA fragments into long filaments. Moreover, these mutant proteins also lost the ability to fully protect ssDNA from micrococcal nuclease digestion. In addition to the conclusion that the C-terminal region is required for multimerization, the results obtained with the C-terminally truncated proteins also provide strong evidence that multimerization is a prominent feature in determining the mode by which p16.7A binds ssDNA. Particularly, the partial protection patterns obtained with the C-terminally truncated proteins in the micrococcal nuclease assays strongly suggest that they are unable to form continuous arrays. Experiments carried out with p16.7A, instead of truncated proteins, also support the view that multimerization is decisive for the mode of ssDNA binding. In vitro crosslinking assays provided direct evidence that p16.7A multimerization is affected at increased salt concentrations, and micrococcal nuclease digestion experiments showed that full protection of the ssDNA was lost under these conditions. Moreover, electron microscopic analyses of p16.7A–ssDNA complexes formed at high salt concentration showed that the formation of long filaments was affected (our unpublished results). In conclusion, the results obtained strongly indicate that the p16.7A–ssDNA complexes formed at low salt concentrations consist of a continuous array of p16.7A bound to the ssDNA and that the ability of p16.7A to form multimers, mediated via interactions that involve the C-terminal region, is required for this mode of ssDNA binding. The in vivo crosslinking experiments provided evidence that native p16.7 also forms multimers in infected cells, suggesting that the results obtained in vitro can be extrapolated to the in vivo situation.

Probably, p16.7A multimerization occurs by one, or a combination of the following two mechanisms. The C-terminal end of one p16.7A molecule would interact with either the C-terminal or with another region of an adjacent p16.7A molecule present in a neighbouring p16.7A dimer. In either mode it is imperative that the C-terminal region is surface exposed. The observation that the polyclonal antibodies against p16.7 hardly recognized the C-terminally truncated proteins in western blot assays indicates that the majority of the epitopes, which are inherently solvent exposed, are located in the C-terminal region.

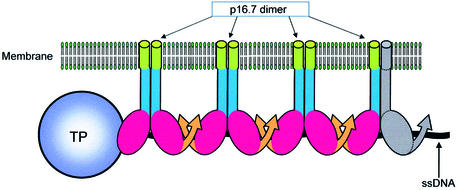

The results obtained in this study together with those obtained earlier (Meijer et al., 2000, 2001b; Serna-Rico et al., 2002) allow us to (i) dissect protein p16.7 into distinct domains and (ii) propose a comprehensive model of the role of p16.7 in membrane-associated organization of φ29 DNA replication in vivo. These features are illustrated schematically in Figure 8. For clarity, one of the two p16.7 monomers forming the rightmost dimer is shown depicted in grey. The different domains of which a p16.7 monomer is composed are (i) an N-terminal membrane anchor (green bar); (ii) a putative coiled-coil domain involved in p16.7 dimerization (blue bar); (iii) a DNA-binding domain (red oval); and (iv) a multimerization domain (orange arrow). Protein p16.7, localized to the membrane by its membrane anchor and in a dimeric form through the formation of a coiled coil, would recruit the φ29 DNA replication intermediates to the membrane of the infected cell by binding to both the parental TP and the displaced ssDNA strand. As a consequence, p16.7 contributes not only to compartmentalization of φ29 DNA replication but probably also to the organization of DNA replication. In this respect it is worth mentioning that the pattern of TP and p16.7 distribution at early infection times are remarkably similar, suggesting that they may be co-localized. At later infection times when φ29 DNA is amplified exponentially, p16.7 and newly synthesized phage DNA also show similar distribution patterns (Meijer et al., 2000). These, together with electron microscopic results indicating that p16.7A binds to the displaced ssDNA regions of φ29 DNA replication intermediates generated during in vitro φ29 DNA replication (Serna-Rico et al., 2002) and the data presented in this work that p16.7A interacts with TP, form a strong body of evidence that the model presented in Figure 8 is likely to reflect the in vivo function of p16.7.

Fig. 8. Schematic presentation of the modular organization of p16.7 and its proposed role in attachment of φ29 DNA replication intermediates to the membrane of the infected cell. The membrane bilayer and protein p16.7 dimers are indicated. Only one end of a TP-containing displaced ssDNA strand of a φ29 DNA replication intermediate is shown. A single p16.7 monomer, the one forming part of the rightmost dimer shown, is illustrated in grey. The N-terminal membrane anchor and the putative coiled-coil domain are shown as green and blue bars, respectively. The putative DNA-binding domains are shown as red ovals and curved orange arrows illustrate the multimerization domains. For simplicity, the C-terminal end of the p16.7 monomer contacting the TP is omitted. The proteins and DNA are not drawn to scale.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains, bacteriophages and growth conditions

Bacillus subtilis 110NA (trpC2, spo0A3, su–; Moreno et al., 1974) was used for φ29 infections. Cells were grown at 37°C in Luria–Bertani medium supplemented with 5 mM MgSO4. Logarithmically growing cells (OD600 0.4–0.5) were infected with mutant φ29 phage sus14(1242) (Jiménez et al., 1977) at a multiplicity of 5. The suppressor sensitive mutation in the holin-encoding gene 14 of phage sus14(1242) has no effect on phage DNA replication or phage morphogenesis, but delays lysis of the infected cell, which therefore does not interfere with the in vivo crosslinking assays. Escherichia coli strain JM109 [F′ traD36 lacIq (lacZ)M15 proA+B+/e14-(McrA–) (lac-proAB) thi gyrA96 (Nalr) endA1 hsdR17 (rk– mk+) relA1 supE44 recA1; Yanish-Perron et al., 1985] was used for cloning and overexpression of proteins. Chloramphenicol and ampicillin were added to E.coli cultures at final concentrations of 10 and 100 µg/ml, respectively.

DNA techniques

All DNA manipulations as well as transformation of CaCl2-treated E.coli cells were carried out according to Sambrook et al. (1989). Restriction enzymes were used as indicated by the suppliers. [α-32P]dATP and [γ-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) were obtained from Amersham International plc. Plasmid DNA was isolated using Wizard Plus DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). DNA fragments were isolated from gels using the Qiaquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA). The dideoxynucleotide chain-termination method (Sanger et al., 1977) with Sequenase (United States Biochemicals sequencing kit) was used for DNA sequencing.

PCR techniques

PCRs were carried out essentially as described (Innis and Gelfand, 1990) using the proofreading-proficient Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA, USA). Template DNAs were denatured for 1 min at 94°C. Next, DNA fragments were amplified in 30 cycles of denaturation (30 s; 94°C), primer annealing (1 min; 50°C) and DNA synthesis (3 min; 73°C).

Construction of C-terminal gene 16.7A deletion mutants

The appropriate regions of gene 16.7A were amplified by PCR using primer WM7A (5′-CAACGGATCCCGAAACAACAAAAAGAAACA GGAAGC-3′) in combination with primer WM8B (5′-GCAAGCGGC CGCTCAATATAGTTTTTTTCTGATTCTCCAA-3′), WM8C (5′-GC AAGCGGCCGCTCAATTCTCCAATTTCCAGTATGTCCGC-3′), WM8D (5′-GCAAGCGGCCGCTCAGTATGTCCGCTGTGTTCTCTATAT-3′) or WM8E (5′-GCAAGCGGCCGCTCACTCTATATAGTTTAACACTTCCT G-3′). pUSH167A plasmid DNA containing gene 16.7A (Meijer et al., 2001b) was used as template. The PCR products were purified, digested with BamHI and NotI, and cloned into pBSK+ vector (Short et al., 1988) digested with the same enzymes. The plasmid content of some white transformants grown on ampicillin (100 µg/ml), IPTG (1 mM) and Xgal (50 µg/ml)-containing plates was analysed by restriction analysis, and the correctness of the insert was subsequently verified by sequence analysis. After digestion with BamHI and NotI, the desired insert was isolated and cloned into pUSH1 (Schön and Schumann, 1994) digested with the same enzymes.

Overexpression and purification of p16.7A and its C-terminal deletion derivatives

Protein p16.7A and the deletion derivatives pΔ5, pΔ10, pΔ15 and pΔ20 were overexpressed and purified using a Ni2+-NTA resin column as described previously (Meijer et al., 2001b).

Gel mobility shift assays

Incubation mixtures contained, in a final volume of 20 µl, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 4% Ficoll 400, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 10 mM DTT, the indicated labelled DNA fragment and the indicated amount of protein. After incubation for 10 min at 4°C, the samples were subjected to electrophoresis in 4% non-denaturing polyacrylamide (80:1) gels containing 12 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.5 and 1 mM EDTA, and run at 4°C using a running buffer containing 12 mM Tris-acetate pH 7.5 and 1 mM EDTA at 70 V for 6 h. To study the effect of salt, 100 mM NaCl was used in the binding buffer, gel and running buffer.

Glycerol gradients

The indicated amounts of proteins were subjected to a 15–30% linear glycerol gradient containing 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA and 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol and the indicated NaCl concentration, and run as described previously (Serna-Rico et al., 2000). After fractionation of the gradient, aliquots of each fraction were analysed by SDS–PAGE or western blotting (performed as described by Serna-Rico et al., 2002).

Crosslinking assays

In vitro crosslinking assays using DSS as crosslinking agent were performed as described previously (Meijer et al., 2001b). In the case of in vivo crosslinking, 1.5 ml samples of a B.subtilis culture, withdrawn 15 min after φ29 infection, were centrifuged and resuspended in 200 µl buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 4% sucrose and the appropriate DSS concentration (0, 5, 10, 15 or 20 mM). After 20 min incubation in ice, the cells were pelleted, resuspended in 300 µl gel loading buffer and disrupted by sonication. The samples were then processed by SDS–PAGE followed by western blotting.

Electron microscopy of nucleoprotein complexes

The 300 bp right-end φ29 DNA fragment was amplified by PCR and heat denatured to obtain its single-stranded form. Reaction mixtures of 20 µl contained 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 4% Ficoll 400, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 100 ng heat-denatured ssDNA and the indicated amount of protein. After incubation for 10 min at 4°C, 0.1% (v/v) glutaraldehyde was added after which the samples were incubated for a further 5 min at 4°C. Aliquots (5 µl) of these samples were mixed on ice with 0.5 µl benzyldimethylalkylammonium chloride. Complexes were spread on a hypophase as described (Sogo and Thoma, 1989), picked up with a carbon-coated copper grid, stained with 0.5 mM uranyl acetate, dehydrated and rotary shadowed with platinum at 10–5 torr. Micrographs were taken in a Jeol 1010 electron microscope at 80 kV.

Micrococcal nuclease digestion assays

Micrococcal nuclease digestion assays were performed using heat-denatured end-labelled 300 bp DNA fragments corresponding to the φ29 right-end genome. Reaction volumes of 20 µl contained, besides the labelled DNA, 25 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, 10 mM DTT, 3 mM CaCl2 and the indicated amount of NaCl and protein. The mixtures were incubated for 10 min at 4°C. Next, unless stated otherwise, 0.5 mU of micrococcal nuclease (USB Corporation, Cleveland, OH, USA) was added and digestion was allowed for 10 min at 4°C. The reaction was stopped upon addition of EDTA to a final concentration of 20 mM and the DNA was precipitated with ethanol in the presence of 10 µg of carrier tRNA. Finally, the fragments were fractionated through 8 M urea-containing polyacrylamide gels (6%) after which the gel was dried and subjected to autoradiography. Protein:ssDNA ratios similar to those in the gel retardation assays were used.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We thank María Teresa Rejas for electron microscopy assistance and J.M.Lázaro for protein purification. This investigation was supported by National Institutes of Health Research Grant 2RO1 GM27242-23, Dirección General de Investigación Científica y Técnica Grant PB98-0645 and an Institutional grant from Fundación Ramón Areces to the Centro Biología Molecular ‘Severo Ochoa’. A.S.R and D.M. were holders of a predoctoral fellowship from ‘Gobierno Vasco’ and ‘Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias’, respectively. The ‘Ramón y Cajal’ program of the Spanish ministry of Science and Technology supported W.J.J.M.

References

- Alani E., Thresher,R., Griffith,J.D. and Kolodner,R.D. (1992) Characterization of DNA-binding and strand-exchange stimulation properties of y-RPA, a yeast single-strand-DNA-binding protein. J. Mol. Biol., 227, 54–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco L., Prieto,I., Gutiérrez,J., Bernad,A., Lázaro,J.M., Hermoso,J.M. and Salas,M. (1987) Effect of NH4+ ions on φ29 DNA–protein p3 replication: formation of a complex between the terminal protein and the DNA polymerase. J. Virol., 61, 3983–3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrysogelos S. and Griffith,J. (1982) Escherichia coli single strand binding protein organizes single-stranded DNA in nucleosome-like units. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 79, 5803–5807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenjaerts F.E., van Oosterhout,J.A. and van der Vliet,P.C. (1994) The Oct-1 POU domain stimulates adenovirus DNA replication by a direct interaction between the viral precursor terminal protein–DNA polymerase complex and the POU homeodomain. EMBO J., 13, 5401–5409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook P.R. (1999) The organization of replication and transcription. Science, 284, 1790–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong R.N. and van der Vliet,P.C. (1999) Mechanism of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells: cellular host factors stimulating adenovirus DNA replication. Gene, 236, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firshein W. (1989) Role of the DNA/membrane complex in prokaryotic DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Microbiol., 43, 89–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick J.T., Eissenber,J.C. and Elgin,S.C.R. (1986) Micrococcal nuclease as a DNA structural probe: its recognition sequences, their genomic distribution and correlation with DNA structure determinants. J. Mol. Biol., 190, 619–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Huici V., Lázaro,J.M., Salas,M. and Hermoso,J.M. (2000) Specific recognition of parental terminal protein by DNA polymerase for initiation of protein-primed DNA replication. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 14678–14683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis M.A. and Gelfand,D.H. (1990) Optimization of PCRs. In Innis,M.A., Gelfand,D.H., Sninsky,J.J. and White,T.J. (eds), PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- Ivarie R.D. and Pène,J.J. (1973) DNA replication in bacteriophage Φ29: the requirement of a viral-specific product for association of Φ29 DNA with the cell membrane of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Virology, 52, 351–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen R.B. and Shapiro,L. (2000) Proteins on the move: dynamic protein localization in prokaryotes. Trends Cell Biol., 10, 483–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez F., Camacho,A., de la Torre,J., Viñuela,E. and Salas,M. (1977) Assembly of Bacillus subtilis phage φ29. 2. Mutants in the cistrons coding for the non-structural proteins. Eur. J. Biochem., 73, 57–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg A. and Baker,T.A. (1992) DNA Replication. W.H. Freeman and Co., San Francisco, CA.

- Lemon K.P. and Grossman,A.D. (1998) Localization of bacterial DNA polymerase: evidence for a factory model of replication. Science, 282, 1516–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer W.J.J., Lewis,P.J., Errington,J. and Salas,M. (2000) Dynamic relocalization of phage φ29 DNA during replication and the role of the viral protein p16.7. EMBO J., 19, 4182–4190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer W.J.J., Horcajadas,J.A. and Salas,M. (2001a) φ29-family of phages. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev., 65, 261–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer W.J.J., Serna-Rico,A. and Salas,M. (2001b) Characterization of the bacteriophage φ29-encoded protein p16.7: a membrane protein involved in phage DNA replication. Mol. Microbiol., 39, 731–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno F., Camacho,A., Viñuela,E. and Salas,M. (1974) Suppressor-sensitive mutants and genetic map of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage φ29. Virology, 62, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas M. (1991) Protein-priming of DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem., 60, 39–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas M., Miller,J.T., Leis,J. and DePamphilis,M.L. (1996) Mechanisms for priming DNA synthesis. In DePamphilis,M.L. (ed.), DNA Replication in Eukaryotic Cells. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, pp. 131–176.

- Sambrook J., Fritsch,E.F. and Maniatis,T. (1989) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Sanger F., Nicklen,S. and Coulson,A.R. (1977) DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 74, 5463–5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schön U. and Schumann,W. (1994) Construction of His6-tagging vectors allowing single-step purification of GroES and other polypeptides produced in Bacillus subtilis. Gene, 147, 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna-Rico A., Illana,B., Salas,M. and Meijer,W.J.J. (2000) The putative coiled coil domain of the φ29 terminal protein is a major determinant involved in recognition of the origin of replication. J. Biol. Chem., 275, 40529–40538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serna-Rico A., Salas,M. and Meijer,W.J.J. (2002) The Bacillus subtilis phage φ29 protein p16.7, involved in φ29 DNA replication, is a membrane-localized single-stranded DNA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem., 277, 6733–6742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short J.M., Fernandez,J.M., Sorge,J.S. and Huse,W.D. (1988) λ ZAP: a bacteriophage λ expression vector with in vivo excision properties. Nucleic Acids Res., 16, 7583–7600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo J.M. and Thoma,F. (1989) Electron microscopy of chromatin. Methods Enzymol., 170, 142–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanish-Perron C., Vieira,J. and Messing,J. (1985) Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene, 33, 103–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]