Abstract

The present study evaluates the potential of third-generation lentivirus vectors with respect to their use as in vivo–administered T cell vaccines. We demonstrate that lentivector injection into the footpad of mice transduces DCs that appear in the draining lymph node and in the spleen. In addition, a lentivector vaccine bearing a T cell antigen induced very strong systemic antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses in mice. Comparative vaccination performed in two different antigen models demonstrated that in vivo administration of lentivector was superior to transfer of transduced DCs or peptide/adjuvant vaccination in terms of both amplitude and longevity of the CTL response. Our data suggest that a decisive factor for efficient T cell priming by lentivector might be the targeting of DCs in situ and their subsequent migration to secondary lymphoid organs. The combination of performance, ease of application, and absence of pre-existing immunity in humans make lentivector-based vaccines an attractive candidate for cancer immunotherapy.

Introduction

The prospects of an antitumor vaccine depend on its ability to induce robust and sustained tumor-specific T cell responses. Since the initiation of such responses is crucially dependent on the presentation of the antigen by DCs, current tumor vaccines are designed to target DCs ex vivo. One approach consists of pulsing DCs in vitro with antigenic peptides before transferring them back to the patient (1–3). In an analogous approach, DCs are transduced with an antigen-recombinant viral vector (4, 5). Transduction is thought to result in better antigen processing and more sustained antigen presentation than pulsing (4, 6). However, the generation and ex vivo manipulation of DCs is laborious and costly. Therefore, a cell-free vaccine that could be easily administered yet would retain the efficacy of the DC-based approach would be a significant improvement. However, as the majority of recombinant viral vectors are derived from vaccines originally designed to prevent viral infections, pre-existing immunity to the parental virus might interfere with their ability to induce potent antitumor immune responses (7).

In this context, the advent of new, efficient gene delivery vehicles may provide a solution. We and others recently introduced lentiviral vectors (lentivectors) as tools for the ex vivo transduction of DCs and the induction of T cell responses (8–11). These third generation lentivectors are designed for in vivo gene therapy and to our knowledge exhibit the most advanced safety features so far included in any viral vector system (12) and thus may be suitable for in vivo administration as a vaccine.

This study characterizes the properties of an in vivo administered lentivector-based vaccine with regard to its cellular targets and its ability to induce antigen-specific CD8+ T cell responses. We observed that lentivector administration transduced DCs that were found in the draining lymph node and in the spleen. In addition, the vaccine induced potent T cell responses as demonstrated by up to 40% antigen-specific cells among the CD8+ subset and high levels of specific cytotoxicity.

Comparative vaccination with transduced DCs demonstrated that in vivo administration of lentivector induces equally strong antigen-specific T cell responses. Moreover, when compared with another cell-free approach, administration of antigenic peptides in combination with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODNs) emulsified in adjuvant, lentivector induced a 3- to 10-fold higher amplitude of response.

Methods

Mice.

B6D2F1 mice (Harlan, Zeist, the Netherlands) were used for Cw3 vaccination. HLA-Cw3 transgenic mice were used as source of antigen-transgenic DCs (13). HLA-A*0201/Kb transgenic mice were used for vaccinations with Melan-A/ELA26–35 (14). These mice were originally provided by Harlan Sprague-Dawley (Indianapolis, Indiana, USA). Mouse experiments were carried out with permission of the “Service Vétérinaire” of the Canton de Vaud, Swiss Confederation.

Lentivector vaccines.

The HLA-Cw3 cDNA was cloned by RT-PCR from P 815 cells stable-transfected with HLA-Cw3 (15) and inserted into lentiviral transfer vector pIRES-EGFPpRRLsin18.PPT.CMV. A minigene encoding the H-2Kd–restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) antigen of HLA-Cw3 (Cw3194–203) (15–17) was inserted in pIRES-EGFPpRRLsin18.PPT.CMV (8). Likewise, a minigene encoding the immunodominant peptide analogue of the HLA-A*0201–restricted Melan-A CTL antigen (ELA26–35) was cloned in pIRES-EGFPpRRLsin18.PPT.CMV. The mutation at position 27 (Ala to Leu) results in increased immunogenicity of the peptide analogue as compared with the wild type (18). Both antigen minigenes contained a start and a stop codon. Preparation of concentrated stocks of third-generation lentivectors was performed as described (8, 19).

PCR detection of integrated virus.

PCR detection of lentivector integration into tissue was performed on genomic DNA from whole lymph nodes and spleen using a seminested approach with GFP-specific primers (forward, 5′-CAAATGGGCGGTAGGCGTGTA-3′; reverse, 5′-TGGGGGTGTTCTGCTGGTAG-3′, nested primer, 5′-GGCCACAAGTTCAGCGTGTCC-3′).

Histology.

Lymph nodes and spleens were embedded in Tissue Tek OCT compound (Miles, Elkhart, Indiana, USA) and snap frozen in 2-methylbutane (Merck, ZH-Dietikon, Switzerland). Cryostat sections (7 μm) were either analyzed directly for GFP fluorescence or fixed in 5% paraformaldehyde for histochemical detection of GFP with rabbit anti-GFP mAb (Aurora, Madison, Wisconsin, USA) for 1 hour at room temperature after rehydration with PBS and blocking of nonspecific background with 1% BSA in PBS. Likewise, CD11c, B220, and CD11b were detected using biotin-conjugated hamster anti-mouse CD11c (HL3, BD Pharmingen, San Jose, California, USA), biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse B220 (RA3-6B2, Caltag Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, California, USA), or biotin-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD11b (M1/70, BD Pharmingen). As secondary antibody for GFP detection, a goat-anti rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa 488 was used (Molecular Probes, Juro AG, Lucerne, Switzerland). CD11c, CD11b, and B220 were stained using Streptavidin Cy3 (Jackson ImmunoResearch; Milan Analytica, La Roche, Switzerland). After washing in PBS, stained sections were mounted with 1,4-diazabicyclo-(2.2.2)-octane (DABCO) mounting media (Sigma-Aldrich, Buchs, Switzerland).

Synthetic peptides and CpG ODNs.

Peptides were synthesized by solid-phase chemistry on a multiple peptide synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). Peptides were over 90% pure (by analytical HPLC). Lyophilized peptides were diluted in DMSO and stored at –20°C. Synthetic CpG ODN 1826 (TCCATGACGTTCCTGACGTT) optimized for mouse vaccination (Coley Pharmaceutical Group Inc., Wellesley, Massachusetts, USA) was dissolved in sterile PBS.

Flow cytometry.

Flow cytometry was performed on a FACSCalibur using Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, California, USA). Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) obtained by tail bleedings were incubated with phycoerythrin-conjugated H2-Kd/Cw3194–203 or HLA-A*0201/ELA26–35 tetramers (prepared in our laboratory) for 30 minutes at 20°C and then washed before incubation with Cychrome-conjugated anti-CD8 mAb 53-6.7 (eBioscience, San Diego, California, USA), FITC-conjugated anti-Vβ10 (B21.5), and APC-conjugated anti-CD62L (Mel-14, prepared in our laboratory) for 20 minutes at 4°C. Erythrocytes were lysed using the FACS Lysing solution (Becton Dickinson).

Transduction of bone marrow–derived DCs.

Bone marrow–derived DCs (BMDCs) cultured in the presence of GM-CSF (20) were transduced at day 5 of culture by adding concentrated virus (MOI, 100; vector concentration, 5 × 104 expression-forming units [EFUs] per microliter) to the culture medium as described (8). Three days later, the cells were extensively washed and administered to mice.

Vaccination.

Peptide vaccination was carried out by subcutaneously injecting 50 μg of peptide and 50 μg of CpG ODNs emulsified in 50 μl of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) and 50 μl of PBS into the base of the tail. Recombinant lentivectors were administered by subcutaneously injecting 2 × 107 EFUs in 100 μl of PBS either into the footpad or into the base of the tail. DC-based vaccination was carried out by administering 5 × 105 DCs containing 25–30% lentivector-transduced or Cw3-transgenic DCs into each hind footpad of mice.

CTL assays.

In vivo CTL assays were performed as described previously (21). Briefly, splenocytes from syngeneic mice were pulsed or left nonpulsed with Cw3 antigenic peptide (RYLKNGKETL). The pulsed fraction was then labeled in PBS containing CFSE at 0.6 μM, and the nonpulsed fraction was labeled in 0.04 μM CFSE. Both fractions were adjusted to similar cell content (50:50 ratio), pooled, and injected into the tail vein at 107 cells per mouse on day 8 after vaccination with Cw3 cDNA lentivector. Twelve hours later, mice were bled, and the disappearance of peptide-pulsed cells was determined by FACS analysis. By comparing the ratio of the pulsed (high fluorescence intensity) to the nonpulsed fraction (low fluorescence intensity), the percentage of specific killing was established according to the following equation: 100 – ([percentage pulsed] × [percentage nonpulsed]–1 × 100).

Results

Targeting of DCs in situ by lentivector.

Viruses can be potent inducers of T cell immunity but also dispose of many ways to avoid immune recognition. This has to be taken into account when evaluating the potential of a recombinant virus for the purpose of vaccination. As T cell responses critically depend on the presentation of viral antigens by the MHCs of professional APCs (22, 23), the tropism of a recombinant virus may determine its immunogenicity. The lentivector used in this study was pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein and thus is taken up through the normal endocytotic pathways. Therefore, it is able to transduce a wide variety of cells in vitro, including DCs (8, 9).

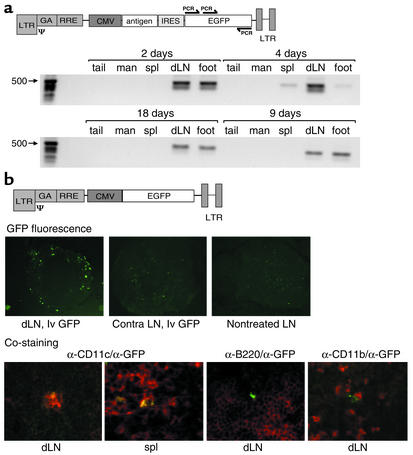

We analyzed the tissue distribution and the target cells after administration of lentivector vaccine into one footpad of mice by a sensitive PCR assay and by immunohistochemical analysis of lymph nodes and spleen. For PCR analysis, genomic DNA was isolated from the site of injection, the draining (popliteal) lymph node, the spleen, and — as controls — the mandibular lymph nodes and the tip of the tail. Amplification of GFP-specific sequences included in the lentivector vaccine was detected, apart from in the injection site, in only the draining popliteal lymph node and the spleen (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Tissue distribution of lentivector obtained after in vivo administration into footpads of mice. (a) Detection of integrated lentivector at the site of injection (foot), the draining lymph node, and the spleen but not in the mandibular lymph node and the tip of the tail. Vector integration was detected by amplification of vector-derived GFP sequence with specific primers (arrows) using seminested PCR. dLN, draining lymph node; spl, spleen; man, mandibular lymph node. (b) Histological analysis of GFP expression after administration of lentivector into one hind footpad. The upper panel shows GFP fluorescence of frozen sections of popliteal lymph nodes 2.5 days after injection of CMV-GFP lentivector (lvGFP) or PBS (nontreated) into the footpad. The contralateral popliteal lymph node (contra) of a treated mouse is also shown. Magnification, ×100. The lower panel shows double immunofluorescence analysis of draining lymph nodes and spleen 2.5 days after injection of CMV-GFP lentivector using anti-GFP antibodies (green) counterstained with anti-CD11c, anti-CD11b, and anti-B220 antibodies (red). Magnification, ×400. The use of a CMV-GFP lentivector for immunofluorescence was necessary, because with the bicistronic vaccine constructs (antigen-IRES-GFP), GFP fluorescence was too low to be picked up in histology. For PCR analysis of the GFP sequence, the actual vaccine vector was used.

Monitoring GFP fluorescence on frozen sections of total lymph nodes revealed the presence of transduced cells in the cortex of the draining lymph node but not in lymph nodes of nontreated animals or in the contralateral lymph node of lentivector-treated mice (Figure 1b, upper panels). This fluorescence was found 2–3 days after administration of lentivector. Sections prepared 10 days after lentivector administration did not show any GFP fluorescence (data not shown). The observation that integrated vector persisted at later time points, as revealed by PCR, might be due to the greater sensitivity of this assay.

To identify which cell types were transduced in vivo by lentivector, we combined immunofluorescence analysis of GFP expression with markers specific for DCs, macrophages, and B cells. Double-positive cells were observed with an antibody against the DC marker CD11c (Figure 1b, lower panels) but not with antibodies to either the B cell marker CD45R/B220 or the macrophage marker CD11b (Figure 1b) in any of the sections analyzed (n = 30). Although the majority of GFP-positive cells were CD11c positive, about 10% of GFP-positive cells were negative for all of the markers tested.

Induction of CTL responses upon lentivector administration.

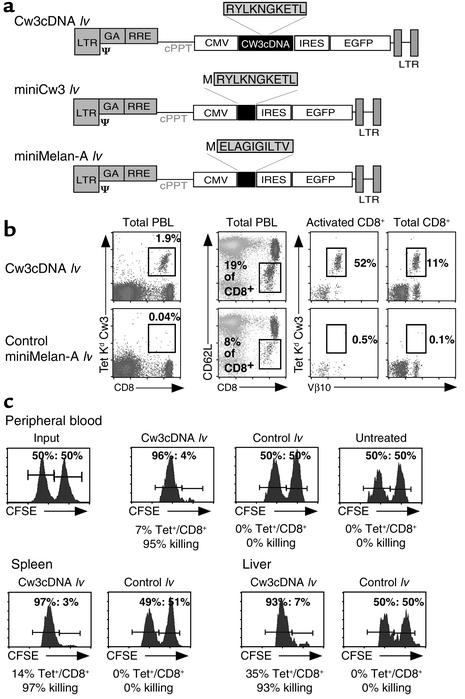

We then tried to elucidate whether the observed in vivo targeting of DCs by lentivector vaccine correlated with efficient induction of CTL responses. To that end, we vaccinated mice with a lentivector bearing a CTL-defined antigen derived from human HLA-Cw3 (referred to throughout the text as Cw3194–203). The ensuing response was characterized by monitoring the CD8+ T cell response specific to H-2 Kd–restricted Cw3194–203 in PBLs of vaccinated mice by staining with H-2 Kd Cw3194–203 tetramers (17, 24). In combination with tetramer staining, we used antibodies against the Vβ10 T cell receptor segment, since the majority of Cw3-specific cells are Vβ10+ (25). A lentivector bearing the cDNA of HLA-Cw3 (Cw3 cDNA lv) (Figure 2a) was administered by injecting 2.5 × 107 EFUs into the hind footpads of mice. As a negative control, the same amount of a lentivector expressing an irrelevant antigen (Melan-A) was used (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Direct administration of lentivector results in the induction of Cw3 CTL responses. (a) Schematic representation of the constructs used to generate lentiviral vectors. (b) Phenotypic characterization of peak response (day 9). PBLs were analyzed for the cell surface markers CD8, CD62L (downregulated upon activation), and TCR Vβ10. The T cell receptor specificity was examined using H-2Kd/Cw3 tetramers in combination with Vβ10 staining. The proportion of Cw3-specific cells among total PBLs obtained after direct in vivo administration of lentivector is depicted. As a control, an irrelevant (miniMelan-A) lentivector was administered. This is followed by a detailed analysis of the immune response, featuring the proportion of activated CD8+ cells, the proportion of Cw3-specific cells in the activated compartment, and the proportion of Cw3-specific cells among total CD8+ cells. (c) CTL assay showing the in vivo elimination of target cells transferred to vaccinated mice. Syngeneic splenocytes, pulsed with Cw3 antigenic peptide (RYLKNGKETL) and labeled with CFSE at high concentration, were transferred to vaccinated mice 1 day before peak response along with the same number of nonpulsed splenocytes labeled with CFSE at a lower concentration. Twelve hours later, the disappearance of peptide-pulsed cells was determined by FACS analysis in PBL, spleen, and liver. By a comparison of the ratio of pulsed to nonpulsed cells, the percentage of specific killing was calculated. Control lv, lentivector expressing an irrelevant CTL epitope; miniMelan-A lv, ELA26–35 minigene lentivector.

The vaccines were well tolerated, and a swelling at the site of infection was usually resolved after 1 day. Administration of Cw3 cDNA lentivector resulted in the induction of a massive T cell response (Figure 2b), peaking at day 9 and characterized by the presence of 10–40% antigen-specific cells (H-2 Kd Cw3194–203 tetramer-positive) among total CD8+ cells (Figure 2b). In comparison with the irrelevant lentivector control, we also observed a large increase in the proportion of activated CD8+ cells (CD62L–/CD8+) (Figure 2b).

In order to test the functional capacity of the induced antigen-specific CD8+ cells, we performed in vivo CTL assays using as targets syngeneic spleen cells pulsed with antigenic peptide that were transferred to vaccinated mice (21). Before transfer, the pulsed cells were labeled with CFSE, allowing us to monitor their fate in vivo by FACS analysis in tissue such as blood, spleen, and liver. As an internal control, the same number of nonpulsed splenocytes was labeled with a lower intensity of CFSE and coinjected with the pulsed cells. The shift in the ratios of the two CFSE-positive populations provoked by the in vivo elimination of pulsed cells allowed us to calculate the percentage of specific killing that had occurred. Transfer of pulsed and nonpulsed target cells into vaccinated mice was performed 1 day before the peak of the T cell response. Analysis of PBLs, splenocytes, and liver lymphocytes was carried out 12 hours after transfer, and the proportion of H-2 Kd Cw3194–203 tetramer+/CD8+ cells, as well as the shift in the ratios of the two CFSE-labeled populations, was determined by FACS analysis.

As demonstrated in Figure 2c, vaccination with Cw3 cDNA lentivector resulted in an almost complete (over 95%) elimination of the pulsed, CFSEhigh population. In marked contrast, vaccination with a lentivector bearing an irrelevant CTL-defined antigen did not result in significant killing. Moreover, the observed killing activity induced by vaccination with Cw3 cDNA lentivector was systemic, as was demonstrated by the simultaneous and almost complete disappearance of pulsed targets in spleen and liver of vaccinated mice.

Comparative efficiency of direct administration of lentivector with transfer of transduced DCs or peptide/CpG/adjuvant vaccination.

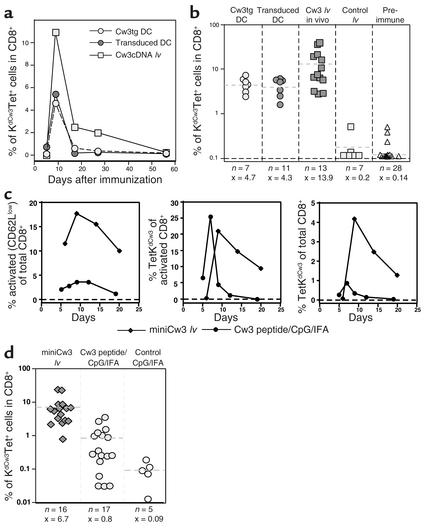

Having established that administration of lentivector bearing a T cell antigen resulted in strong CTL responses, we next wanted to compare its potency with other currently used vaccine protocols. Among these, administration of ex vivo–transduced DCs has set the standards in experimental T cell vaccination. For ex vivo DC transduction, the same lentivector bearing the cDNA of HLA-Cw3 (Cw3 cDNA lv) was used as for direct in vivo administration. As described previously (8), DC-based vaccination was performed by injecting transduced BMDCs into the hind footpads of mice (8). As a control for the influence of the viral vector on immune responses, we transferred BMDCs of Cw3 transgenic mice.

Kinetic analysis of the response (Figure 3a) revealed that with all three vaccines, the peak of response was reached around day 9. Subsequently, the proportion of Cw3-specific cells diminished rapidly to reach near preimmune levels by day 50. Comparison of the proportion of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells at peak response with the different vaccination approaches demonstrated that direct administration of lentivector resulted, on average, in a higher amplitude of the response (Figure 3b), with maximal responses of up to 42% of antigen-specific cells among total CD8+ T cells.

Figure 3.

Comparative analysis of the CD8+ T cell response as induced by lentivector administration, DC-based vaccination, and peptide/CpG/adjuvant vaccination. (a) Comparative vaccination with transgenic DCs, transduced DCs, and direct in vivo administration of lentivector. Mice were vaccinated and PBLs were analyzed by FACS analysis as described. Evolution of the Cw3-specific population over time is shown. All graphs show individual mice that were representative of at least seven mice used for each condition in at least three independent experiments. (b) Proportion of Cw3-specific cells in the CD8+ compartment as determined at peak response with all vaccination conditions plus preimmune levels (dashed lines and x = average, n = number of mice tested). (c) Comparative vaccination with Cw3 minigene lentivector and Cw3 peptide/CpG/IFA vaccination. Shown are time courses of the proportion of activated CD8+ cells and the proportion of Cw3-specific cells within the activated population followed by the proportion of Cw3-specific cells in the CD8+ population. (d) Proportion of Cw3-specific cells in the CD8+ compartment as determined at peak response (day 9 for lentivector vaccination and day 7 for peptide-adjuvant vaccination) of all mice tested (dashed lines and x = average, n = number of mice tested).

A further step in the assessment of the lentivector vaccine was its comparison with another cell-free vaccine: peptide/CpG/adjuvant vaccination. We recently demonstrated that vaccination using synthetic antigenic peptide in combination with CpG ODNs emulsified in IFA was able to induce relatively potent T cell responses (26). The comparison of lentivector vaccine with Cw3194–203 peptide/CpG/IFA was done using a lentivector bearing a minigene that encoded the HLA-Cw3 (Cw3194–203) derived peptide. Both vaccines were administered subcutaneously in the base of the tail because of the relatively high volume of the peptide-adjuvant emulsion. The immune response induced by lentivector or peptide/CpG/adjuvant vaccination was evaluated by monitoring the evolution of parameters such as activation of CD8+ cells and the proportion of Cw3-specific cells among activated and total CD8+ cells (Figure 3c). The most obvious difference between the two vaccines is the 10-fold higher level of activated CD8+ cells induced by the lentivector vaccine. This results in turn in a higher proportion of Cw3-specific cells among total CD8+ cells. Another difference is that 100% of the mice treated with lentivector vaccine mounted a Cw3-specific response, whereas peptide/CpG/adjuvant vaccination achieved a success rate of only 70% (Figure 3d).

Inducing Melan-A–specific CD8+ T cell responses by direct lentivector administration.

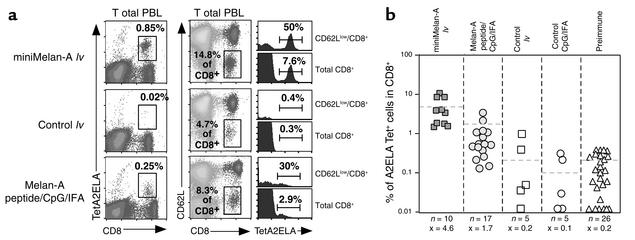

The efficacy of direct in vivo administration of lentivector as demonstrated in the Cw3 model was then evaluated in a more clinically relevant model system involving a modified CTL-defined antigen derived from the human melanoma-associated differentiation antigen Melan-A/MART-1 (27, 28). This HLA-A*0201–restricted Melan-A antigenic peptide (referred to throughout the text as ELA26–35) was expressed in lentivector vaccines as a minigene (Figure 1a). Vaccination and characterization of the ensuing immune response was then carried out in HLA-A*0201/Kb transgenic mice (A2/Kbmice). In addition to endogenous MHC class I molecules, these mice express a chimeric human/mouse MHC I molecule composed of the α1 and α2 domains of HLA-A2.1 and the α3, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic domains of H-2Kb (14). The murine elements of the chimeric class I molecule are required for efficient interaction with mouse β2-microglobulin and the CD8 coreceptor.

With direct administration of ELA26–35 minigene lentivector, we observed a peak of the response at day 14, whereas with peptide/CpG/IFA vaccination the peak was reached at day 7, similar to the situation in the Cw3 antigen model. A representative example of these peak responses is shown in Figure 4a. Using HLA-A2/ELA26–35 tetramers to detect Melan-A–specific CD8+ T cells, we observed a strong, specific response in mice immunized with ELA26–35 minigene lentivector but not in those vaccinated with an irrelevant vector. A comparison of this response to that obtained with peptide/CpG/IFA vaccination shows that ELA26–35 minigene lentivector induces more than twofold higher levels of ELA26–35-specific cells among total CD8+ cells (Figure 4, a and b) and more than threefold higher levels among total PBLs (Figure 4a). As seen with the Cw3 model, this is a direct consequence of the higher levels of CD8+ T cell activation induced by lentivector and the higher proportion of ELA26–35-specific cells contained in the activated population.

Figure 4.

Induction of a Melan-A–specific CD8+ T cell response in HLA-A*0201/Kb transgenic mice vaccinated by administration of lentivector encoding the Melan-A CTL epitope ELA26–35. As controls, a lentivector expressing an irrelevant CTL epitope and the administration of ELA26–35 peptide in combination with CpG and IFA were used. (a) Phenotypic characterization of the peak of immune response (day 14 for lentivector vaccination and day 7 for peptide/CpG/adjuvant vaccination) of individual mice. Melan-A–specific cells among total PBLs are shown in the first row of panels; the percentage of tetramer-positive cells is indicated. The proportion of activated CD8+ cells and the percentages of Melan-A–specific cells contained therein and in total CD8+ cells are displayed in histograms. (b) Proportion of Melan-A–specific CD8+ cells at peak response of all individual mice tested. (Dashed lines and x = average, n = number of mice tested per condition).

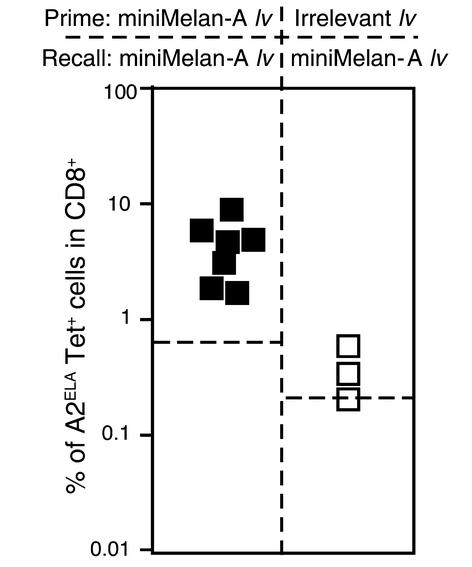

Recall responses to lentivector vaccination.

After the characterization of the strong and sustained primary responses induced by ELA26–35 minigene lentivector, we next evaluated whether a secondary challenge with the same vector would be effective. At the same time, we tested whether antivector immunity had been established during primary immunization. To that end, we performed recall immunizations with the same dose of ELA26–35 minigene lentivector 60 days after primary vaccination in mice primed with either ELA26–35 minigene lentivector or with an irrelevant lentivector not bearing the ELA26–35 CTL-defined antigen.

Mice that had been primed with an irrelevant lentivirus were unable to mount a significant ELA26–35-specific T cell response (Figure 5). This indicated that primary immunization with lentivector resulted in the induction of antivector immunity. However, ELA26–35 minigene lentivector–primed mice responded with similar kinetics and amplitude as seen during the primary response (Figure 5 and data not shown).

Figure 5.

Recall immunizations with miniMelan-A lentivector 60 days after primary immunization with either miniMelan-A lentivector or an irrelevant lentivector. Indicated is the proportion of Melan-A–specific CD8+ cells obtained at the peak of recall response of all individual mice tested (dashed lines indicate the average levels of ELA26–35-specific cells present before recall immunization).

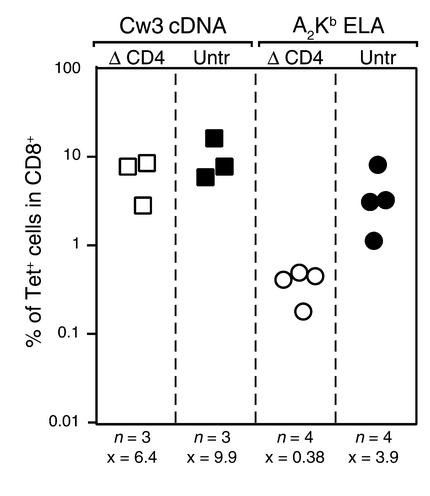

Dependence of lentivector-induced CTL responses on CD4+ T cell help.

Most CD8+ T cell responses are dependent on help mediated by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells (29). To address the role of CD4 T cells in CTL responses induced by lentivector, we vaccinated mice that were depleted or not of CD4+ T cells. Depletion was carried out by injecting the anti-CD4 mAb GK 1.5 (30) 2 days before vaccine inoculation. This resulted in less than 2% remaining CD4+ T cells by the day of vaccine inoculation (data not shown). Helper dependency was evaluated both in the Cw3 and the Melan-A/A2/Kb antigen models.

Although vaccination with Cw3 cDNA lentivector was only slightly affected by CD4+ T cell depletion, administration of ELA26–35 minigene lentivector to CD4-depleted mice resulted in dramatically decreased proportions of antigen-specific T cells (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Influence of CD4+ T cells on induction of CD8+ T cell responses by lentivector vaccine. Mice depleted of CD4+ T cells or nondepleted were vaccinated with lentivector vaccine. Indicated are the T cell responses at peak response of groups of mice in the Cw3 model vaccinated with Cw3 cDNA lv and the Melan-A/A2/Kb antigen model vaccinated with ELA26–35 minigene lentivector (x = average, n = number of mice tested per condition). ΔCD4, mice depleted of CD4+ T cells; untr, nondepleted mice.

Discussion

Currently, there is no vaccine available that is able to cure cancer. There is, however, evidence that antitumor vaccination can induce specific antitumor T cell responses and even tumor regression (2, 3, 31). In the overwhelming majority of cases, these regressions were only transient, suggesting that the T cell responses induced might not have been strong and sustained enough (32). On the basis of these observations, the possibility exists that an optimized vaccination protocol may lead to stronger and curative antitumor T cell responses.

Toward this end, we evaluated lentiviral vector as a new candidate T cell vaccine. Third-generation lentivector was chosen because of its advanced safety profile, allowing its administration in vivo, and because of the presumed absence of pre-existing antivector immunity in humans. To characterize the properties of lentivector vaccine, we studied its transduced targets and its ability to induce CTL responses in vivo.

In a recent report, the administration of lentivector into the tail vein of mice resulted in transduction in both the liver and the spleen. Within these organs, and particularly in the spleen, the cellular targets of lentivector included a prominent proportion of cells that displayed some markers characteristic of professional APCs (33). However, no clear evidence for the transduction of bona fide DCs was provided.

In our study, lentivector was injected subcutaneously into the footpads, and integrated vector was found mainly at the site of injection, the draining lymph node, and the spleen. We were further able to demonstrate that most transduced cells in the lymphoid organs were CD11c+ DCs. The presence of transduced DCs in the draining lymph node and the spleen could be the result of transduction of resident DCs in situ or of migration of DCs that had been transduced at the site of injection. In the latter scenario, lentivector-induced maturation would then result in the migration of DCs to the draining lymph node where, upon presentation of the antigen, they would be able to prime naive T cells. In this context, the ability of lentivector to transduce nondividing cells (34) may be crucial for its efficacy as a vaccine, since immature DCs are thought to be nondividing (35). The observation that the majority of transduced cells found in the spleen and draining lymph nodes are DCs further supports this theory, since it is unlikely that free viral particles reaching the lymph node or spleen would exclusively infect DCs.

Our observations support the idea that T cell responses obtained after lentivector administration are due to direct priming of CTL precursors in situ. In view of the strength of the response as compared with the relative paucity of transduced DCs, an additional involvement of cross-priming by antigen taken up by DCs at the site of injection cannot, however, be excluded.

In order to quantitate the efficiency of lentivector vaccination, we chose the direct monitoring of antigen-specific T cells by tetramer staining and, in the initial characterization of the Cw3 cDNA lentivector, an in vivo CTL assay. We show that lentivector administration induces high levels of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells that display a high CTL activity in vivo. Moreover, although quantitative differences in the outcome of distinct vaccination protocols are difficult to evaluate, the comparison with two of the major existing approaches, peptide/adjuvant vaccination and transfer of antigen-transduced DCs, clearly demonstrated that direct administration of lentivector induces a highly effective antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response.

Since most antitumor T cell vaccination protocols rely on a prime boost strategy, we evaluated whether lentivector administration resulted in the induction of antivector immunity. Because of the failure to induce a Melan-A–specific response in mice that had been primed with an irrelevant lentivector, we presume that antivector immunity had been established. This could be a potentially limiting factor for repetitive lentivector immunization that needs to be examined further. Nevertheless, the induction of antivector immunity did not prevent repetitive vaccination from being effective when the Melan-A minigene vector was used for priming.

As a further step in the characterization of the lentiviral vaccine, we addressed the dependency of the CD8+ T cell response on help by CD4+ T cells. According to a popular model, T cell help is thought to augment CD8+ responses indirectly through the activation of DCs (36–38). This implies that the action of CD4+ T cell help could be substituted by any another mechanism that leads to appropriate DC activation, including transduction with a recombinant vector. When assessing helper dependency in the Cw3 and the Melan-A/A2/Kb antigen models, we found that the two models differ in their dependency on CD4+ T cell help. Whereas with Cw3 no significant difference in the response was observed whether CD4+ T cells were present or not, vaccination with the ELA26–35 minigene lentivector heavily relied on the presence of CD4+ T cells. In the latter case, it appears that a helper epitope must have been provided either by the GFP marker or the viral particle, since the vector expresses only the CTL antigen of Melan-A.

A possible explanation for the divergence in the dependency on CD4+ T cells could be provided by recent data demonstrating that a high frequency of CTL precursors can compensate for CD4 help (39, 40). According to this scenario, the responses seen in the Cw3 model would have been mediated by CD4-independent help, whereas in the Melan-A/A2/Kb model with low precursor frequencies (41), the presence of CD4+ T cells is needed to induce a CD8+ T cell response.

In conclusion, data presented here demonstrate the efficacy of direct in vivo administration of lentiviral vectors for the induction of antigen-specific CTL responses. A decisive factor for this efficacy appears to be the in vivo targeting of DCs. From a practical point of view, our results demonstrate that the time-consuming and costly steps currently used to elicit tumor-specific CTL responses through the transfer of ex vivo–manipulated DCs could be replaced by the much simpler direct in vivo administration of antigen-recombinant lentivectors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very grateful to the lab of L. Naldini for providing us with the lentiviral vector system, G. Badic for expert technical assistance with histology, and R. Voyle for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported in part by a fellowship from the Gabriella Giorgi-Cavaglieri Foundation (to H.R. MacDonald). L. Chapatte and F. Lévy are supported by a grant from the Swiss National Funds. F. Lévy is partially supported by an investigator award from the Cancer Research Institute.

Footnotes

Isabelle Miconnet’s present address is: INSERM 487, Institut Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France.

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: oligodeoxynucleotide (ODN); cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL); 1,4-diazabicyclo-(2.2.2)-octane (DABCO); peripheral blood lymphocyte (PBL); bone marrow–derived DC (BMDC); expression-forming unit (EFU); incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA).

References

- 1.Zitvogel L, et al. Therapy of murine tumors with tumor peptide–pulsed dendritic cells: dependence on T cells, B7 costimulation, and T helper cell 1–associated cytokines. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:87–97. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nestle FO, et al. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate–pulsed dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 1998;4:328–332. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thurner B, et al. Vaccination with mage-3A1 peptide-pulsed mature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1669–1678. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brossart P, Goldrath AW, Butz EA, Martin S, Bevan MJ. Virus-mediated delivery of antigenic epitopes into dendritic cells as a means to induce CTL. J. Immunol. 1997;158:3270–3276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song W, et al. Dendritic cells genetically modified with an adenovirus vector encoding the cDNA for a model antigen induce protective and therapeutic antitumor immunity. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1247–1256. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Germain RN, Margulies DH. The biochemistry and cell biology of antigen processing and presentation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1993;11:403–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, et al. Immunizing patients with metastatic melanoma using recombinant adenoviruses encoding MART-1 or gp100 melanoma antigens. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1894–1900. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.24.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esslinger C, Romero P, MacDonald HR. Efficient transduction of dendritic cells and induction of a T-cell response by third-generation lentivectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 2002;13:1091–1100. doi: 10.1089/104303402753812494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gruber A, Kan-Mitchell J, Kuhen KL, Mukai T, Wong-Staal F. Dendritic cells transduced by multiply deleted HIV-1 vectors exhibit normal phenotypes and functions and elicit an HIV-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in vitro. Blood. 2000;96:1327–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zarei S, Leuba F, Arrighi JF, Hauser C, Piguet V. Transduction of dendritic cells by antigen-encoding lentiviral vectors permits antigen processing and MHC class I–dependent presentation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2002;109:988–994. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.124663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salmon P, et al. Transduction of CD34+ cells with lentiviral vectors enables the production of large quantities of transgene-expressing immature and mature dendritic cells. J. Gene Med. 2001;3:311–320. doi: 10.1002/1521-2254(200107/08)3:4<311::AID-JGM198>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zufferey R, et al. Self-inactivating lentivirus vector for safe and efficient in vivo gene delivery. J. Virol. 1998;72:9873–9880. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9873-9880.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dill O, Kievits F, Koch S, Ivanyi P, Hammerling GJ. Immunological function of HLA-C antigens in HLA-Cw3 transgenic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:5664–5668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vitiello A, Marchesini D, Furze J, Sherman LA, Chesnut RW. Analysis of the HLA-restricted influenza-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte response in transgenic mice carrying a chimeric human-mouse class I major histocompatibility complex. J. Exp. Med. 1991;173:1007–1015. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.4.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maryanski JL, Accolla RS, Jordan B. H2-restricted recognition of cloned HLA class I gene products expressed in mouse cells. J. Immunol. 1986;136:4340–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bour H, Horvath C, Lurquin C, Cerottini JC, MacDonald HR. Differential requirement for CD4 help in the development of an antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response depending on the route of immunization. J. Immunol. 1998;160:5522–5529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maryanski JL, Pala P, Corradin G, Jordan BR, Cerottini JC. H-2-restricted cytolytic T cells specific for HLA can recognize a synthetic HLA peptide. Nature. 1986;324:578–579. doi: 10.1038/324578a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valmori D, et al. Enhanced generation of specific tumor-reactive CTL in vitro by selected Melan-A/MART-1 immunodominant peptide analogues. J. Immunol. 1998;160:1750–1758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dull T, et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J. Virol. 1998;72:8463–8471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8463-8471.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inaba K, et al. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J. Exp. Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barchet W, et al. Direct quantitation of rapid elimination of viral antigen-positive lymphocytes by antiviral CD8(+) T cells in vivo. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000;30:1356–1363. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(200005)30:5<1356::AID-IMMU1356>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigal LJ, Crotty S, Andino R, Rock KL. Cytotoxic T-cell immunity to virus-infected non-haematopoietic cells requires presentation of exogenous antigen. Nature. 1999;398:77–80. doi: 10.1038/18038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sigal LJ, Rock KL. Bone marrow–derived APCs are required for the generation of cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to viruses and use transporter associated with antigen presentation (TAP)-dependent and -independent pathways of antigen presentation. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1143–1150. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bour H, Michielin O, Bousso P, Cerottini JC, MacDonald HR. Dramatic influence of V beta gene polymorphism on an antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response in vivo. J. Immunol. 1999;162:4647–4656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacDonald HR, Casanova JL, Maryanski JL, Cerottini JC. Oligoclonal expansion of major histocompatibility complex class I–restricted cytolytic T lymphocytes during a primary immune response in vivo: direct monitoring by flow cytometry and polymerase chain reaction. J. Exp. Med. 1993;177:1487–1492. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.5.1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miconnet I, et al. CpG are efficient adjuvants for specific CTL induction against tumor antigen-derived peptide. J. Immunol. 2002;168:1212–1218. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coulie PG, et al. A new gene coding for a differentiation antigen recognized by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes on HLA-A2 melanomas. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:35–42. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawakami Y, et al. Identification of the immunodominant peptides of the MART-1 human melanoma antigen recognized by the majority of HLA-A2-restricted tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:347–352. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malek TR. T helper cells, IL-2 and the generation of cytotoxic T-cell responses. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:465–467. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buller RM, Holmes KL, Hugin A, Frederickson TN, Morse HC., III Induction of cytotoxic T-cell responses in vivo in the absence of CD4 helper cells. Nature. 1987;328:77–79. doi: 10.1038/328077a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenberg SA, et al. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat. Med. 1998;4:321–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu Z, Restifo NP. Cancer vaccines: progress reveals new complexities. J. Clin. Invest. 2002;110:289–294. doi:10.1172/JCI200216216. doi: 10.1172/JCI16216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.VandenDriessche T, et al. Lentiviral vectors containing the human immunodeficiency virus type-1 central polypurine tract can efficiently transduce nondividing hepatocytes and antigen-presenting cells in vivo. Blood. 2002;100:813–822. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Follenzi A, Ailles LE, Bakovic S, Geuna M, Naldini L. Gene transfer by lentiviral vectors is limited by nuclear translocation and rescued by HIV-1 pol sequences. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:217–222. doi: 10.1038/76095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsuno K, Ezaki T, Kudo S, Uehara Y. A life stage of particle-laden rat dendritic cells in vivo: their terminal division, active phagocytosis, and translocation from the liver to the draining lymph. J. Exp. Med. 1996;183:1865–1878. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4+ T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–478. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bennett SR, et al. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–480. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schoenberger SP, Toes RE, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393:480–483. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang B, et al. Multiple paths for activation of naive CD8+ T cells: CD4-independent help. J. Immunol. 2001;167:1283–1289. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mintern JD, Davey GM, Belz GT, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Cutting edge: precursor frequency affects the helper dependence of cytotoxic T cells. J. Immunol. 2002;168:977–980. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Firat H, et al. Comparative analysis of the CD8(+) T cell repertoires of H-2 class I wild-type/HLA-A2.1 and H-2 class I knockout/HLA-A2.1 transgenic mice. Int. Immunol. 2002;14:925–934. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]