Abstract

Expression of the chicken lysozyme gene is upregulated during macrophage differentiation and reaches its highest level in bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated macrophages. This is accompanied by complex alterations in chromatin structure. We have previously shown that chromatin fine-structure alterations precede the onset of gene expression in macrophage precursor cells and mark the lysozyme chromatin domain for expression later in development. To further examine this phenomenon and to investigate the basis for the differentiation-dependent alterations of lysozyme chromatin, we studied the recruitment of transcription factors to the lysozyme locus in vivo at different stages of myeloid differentiation. Factor recruitment occurred in several steps. First, early-acting transcription factors such as NF1 and Fli-1 bound to a subset of enhancer elements and recruited CREB-binding protein. LPS stimulation led to an additional recruitment of C/EBPβ and a significant change in enhancer and promoter structure. Transcription factor recruitment was accompanied by specific changes in histone modification within the lysozyme chromatin domain. Interestingly, we present evidence for a transient interaction of transcription factors with lysozyme chromatin in lysozyme-nonexpressing macrophage precursors, which was accompanied by a partial demethylation of CpG sites. This indicates that a partially accessible chromatin structure of lineage-specific genes is a hallmark of hematopoietic progenitor cells.

During the developmentally regulated transcriptional activation of eukaryotic gene loci, tissue-specific interactions take place between enhancer elements and promoters. These interactions are accompanied by chromatin remodeling events that are required for the formation of stable transcription complexes. A variety of experiments have shown that the onset of gene expression in development is not an all-or-none event but involves the gradual reorganization of chromatin and the ordered recruitment of transcription factors and cofactors. This implies progress through a number of intermediate differentiation stages until a given gene locus acquires a stable and nonreversible chromatin structure that is specific for a terminally differentiated state. This is indeed observed when the developmental potential of a multipotent progenitor cell is restricted to a single lineage.

Experiments in the hematopoietic system demonstrate that the initially broad developmental potential of stem or precursor cells is accompanied by promiscuous expression of a diverse range of lineage-specific marker genes (29, 52, 60). Furthermore, genes not yet expressed in immature precursors can exist in a state in which genes are marked for transcription later in development (26, 38). Subsequent lineage differentiation decisions involve the assembly of lineage-specific genes into transcriptionally active chromatin structures and the epigenetic inactivation of genes involved in alternative cellular fates. However, the molecular details of these processes are largely unknown.

The chicken lysozyme gene is a well-studied marker gene for the myeloid lineage of the hematopoietic system. We employ this locus as a model to analyze epigenetic mechanisms involved in the developmental control of gene regulation at the level of an entire chromatin domain by examining cells representing various macrophage differentiation states, from the multipotent progenitor cell not yet expressing the gene to the terminally differentiated cell type expressing the gene at the maximum level. Lysozyme gene expression in myeloid cells is controlled by at least five cis-regulatory elements. Three enhancers situated 6.1 kb, 3.9 kb, and 2.7 kb upstream of the transcription start site, a silencer element at −2.4 kb, and a complex promoter have been identified (reviewed in reference 10). All active cis-regulatory elements colocalize with DNase I hypersensitive sites in chromatin (17, 18, 30) (Fig. 1). The DNase I-hypersensitive site at the −2.4-kb silencer coincides with a binding site for the enhancer-blocking protein CTCF (4, 5) and is present in all lysozyme-nonexpressing cell types, in myeloid precursor cells, and in unstimulated macrophages (18, 30). Transcription of the lysozyme gene is initially activated in granulocyte-macrophage precursors (CFU-GM); this process requires the presence of the early-acting enhancers at −6.1 kb and −3.9 kb and the promoter. As judged by DNase I-hypersensitive site mapping experiments, a third enhancer at −2.7 kb becomes active later in development (30, 33).

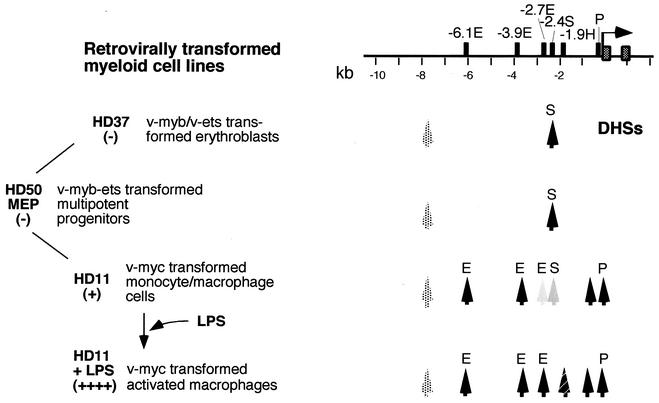

FIG. 1.

Map of the chicken lysozyme locus and cell lines used in this study. The left panel indicates the cell lines used, their position in the myeloid hierarchy, and the level of lysozyme expression in these cells as (−) or (+). The right panel depicts the 5′ regulatory region of the locus and the position of cis-regulatory elements relative to the transcription start (black rectangles). E, enhancer; P, promoter; S, silencer; H, hormone response element. The black vertical arrows indicate the position of DNase I-hypersensitive sites (DHSs) in the different cell lines. The switch in the DNase I-hypersensitive site pattern in the −2.4-kb/−2.7-kb region is indicated by a decrease or increase in shading. A constitutive DNase I-hypersensitive site at −7.9 kb is indicated as a speckled arrow. The transcription start is indicated by a horizontal arrow, and the first two exons are depicted as speckled boxes.

Lysozyme expression is strongly responsive to inflammatory stimuli such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS-stimulated, activated macrophages upregulate lysozyme mRNA expression up to 20-fold from a low basal level (9). This is due to a combination of increased rate of transcription and altered mRNA processing (21) and is accompanied by major changes in the DNase I-hypersensitive site pattern. In these cells, all enhancers are active, a nucleosome over the −2.7-kb enhancer is remodeled, and the DNase I-hypersensitive site at the −2.4-kb silencer disappears (30).

We have recently shown that chromatin reorganization of the lysozyme locus starts even earlier in development than the appearance of DNase I-hypersensitive sites at the −6.1-kb and −3.9-kb enhancers. With UV-photofootprinting, which identifies changes in DNA structure caused by the interaction with proteins (37, 55), we detected the formation of a chromatin fine structure characteristic of lysozyme-expressing macrophages in multipotent myeloid precursor cells. The formation of this chromatin pattern was independent of the stable binding of end-stage transcription factors and actual gene expression (38). Treatment of the cells with trichostatin A, which promotes nucleosome hyperacetylation, demonstrated that the maintenance of this pattern is dynamic in precursor cells but is fixed in macrophage cells, where transcription factor complexes have stably bound and the gene is expressed. Our interpretation of these results is that already early in hematopoietic development, lineage-specific chromatin remodeling events take place and prepare the stage for the assembly of stable transcription complexes.

In the study described here, we wanted to gain more insight into the molecular basis of the stepwise activation of the lysozyme locus at the level of chromatin. To this end, we studied the recruitment of transcription factors important for lysozyme regulation and associated chromatin modification activities across the entire 5′ regulatory region of the lysozyme locus in cells representing different stages of macrophage differentiation by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. We show that activation of the early enhancers was mediated by the binding of a distinct set of transcription factors, such as nuclear factor 1 (NF1) and the Ets family member Fli-1. Only the lysozyme gene enhancers, not the promoter, recruited the histone acetyltransferase (HAT) CREB-binding protein (CBP). Surprisingly, although only activated after LPS treatment, the −2.7-kb enhancer was already fully occupied by transcription factors in unstimulated cells. At each successive step of lysozyme locus activation, levels of histone H3 (K9, K14) acetylation at the enhancers increased and levels of histone H3 (K9) methylation decreased. A particularly interesting finding was that although we did not find any evidence for stable transcription factor binding in multipotent progenitor cells by in vivo footprinting, we were reproducibly able to cross-link members of the NF1 family to lysozyme chromatin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

HD11 (6), HD50 MEP, and HD37 (23) cells were grown in Iscove's medium containing 8% fetal calf serum, 2% chicken serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 292 μg of l-glutamine per ml, and 0.15 mM monothioglycerol. When indicated, the cells were stimulated with 5 μg of LPS per ml (Sigma) for 24 h.

In vivo footprinting analysis.

In vivo dimethylsulfate (DMS) footprinting was performed exactly as described previously (60) except that 1 μg of purified and piperidine-cleaved genomic DNA (49) from DMS-treated HD11 cells, HD50 MEP cells, and HD37 cells was used as starting material for ligation-mediated PCR amplification. DMS-treated and piperidine-cleaved naked genomic DNA was used as a control. Alterations in G(N7) DMS reactivity at lysozyme cis-regulatory elements were visualized by ligation-mediated PCR with the following primers. For the promoter (upper strand), P1 (GACCTCATGTTGCCAGTGTCG), P2 (CAGTGTCGTACACACAGCGGG), and P3 (ACACACAGCGGGACTGCAAGC); for the promoter (lower strand), P351 (TTCAGCACTTGCGAAGAAGAG), P352 (GCGAAGAAGAGCCAAATTTGC), and P353 (GCCAAATTTGCATTGTCAGGA); for the −2.7-kb enhancer (lower strand), U27 (GCTCCTGTTTGAGCAGGTGC), U27A (GGTGCTGCACACTCCCACACTG), and U27A2 (CCACACTGAAACAACAGTC); for the −2.7-kb enhancer (upper strand), D248E1 (CAGCTAAAACCTCATTGTCTTC), D248E2α (TTCAAACTTAGATTTATTATCCCT), and D248E3α (TATCCTCTTCCTTGTAAGCAGACT); for the −3.9-kb enhancer (upper strand), D376 (GAGCTACACAACCCTTCAGC), D376A (CAGCTGTCTCTCCCTTGATGG), and D376B (GATGGCAGCCTGCCCCACAAG); for the −3.9-kb enhancer (lower strand), U42A (CCTGTACAACTTCCTTGTCC), U42B (GTCCTCCATCCTTTCCCAGC), and U42C (CCCAGCTTGTATCTTTGAC); for the −6.1-kb enhancer (upper strand), D6.1U1 (GAACGTTCACTTGACTGGGAT), D6.1U2 (GACTGGGATTACCAGCATGGAGAC), and D6.1U3 (GGAGACATGCTTAGGAGAATG); and for the −6.1-kb enhancer (lower strand), U6.1E1 (TACCGAGGAACAAAGGAAGGCT), U6.1E2 (TTTAGAGAACTGGCAAGCTGT), and U6.1E3 (GAACTGGCAAGCTGTCAAAAAC).

Ligation-mediated PCR-generated bands were quantified on a Molecular Imager FX (Bio-Rad), with Quantity One software.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays and real-time PCR analysis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays were performed as follows: 108 cells were incubated at room temperature with 1/10 cross-linking solution containing 11% formaldehyde, 50 mM HEPES (pH 8), 0.1 M NaC1, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.5 mM EGTA for 30 min and quenched for 5 min with 125 mM glycine (final concentration). After two washes with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, adherent cells (HD11) were scraped into ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline freshly supplemented with 2.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and harvested by centrifugation at 500 × g at 4°C for 5 min. Pellets were resuspended in 40 ml of buffer A containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 8), 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), and 0.25% Triton X-100 and incubated at 4°C for 10 min with gentle shaking. After centrifugation at 500 × g at 4°C for 5 min, cells were resuspended into 40 ml of buffer B containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 8), 200 mM NaC1, 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.5 mM EGTA (pH 8.0), and 0.01% Triton X-100, incubated 10 min, and centrifuged as before.

Nuclei were sonicated on ice (12 times for 30 s each in 1-min intervals) with an MSE Soniprep 150 (Sanyo Gallenkamp PLC) in 5 ml of immunoprecipitation buffer containuing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 2 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaC1, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 2.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride with 5 μl of protease cocktail inhibitor (Sigma, P-8340) and 1 ml of glass beads (212 to 300 μm, acid-washed; Sigma G-1277). After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, chromatin preparations were stored at −80°C in 5% glycerol.

Sonicated chromatin from 107 cells was used for each immunoprecipitation. The volume was first adjusted to 500 μl with fresh immunoprecipitation buffer and precleared with 10 μl of protein A-agarose solution (0.5 μl of 5-mg/ml salmon sperm DNA and 1 μl of 10-mg/ml bovine serum albumin per 10 μl of washed 50% bead suspension (Sigma P-2545) for 1 h at 4°C with a rotating wheel. The protein A-agarose beads were then pelleted for 20 s at 1,500 × g, and the supernatant was incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotating wheel with 5 μl of normal rabbit immunoglobulin G (Upstate Biotechnology, 12-370), 25 μl of anti-CBP and anti-Fli-1 antibodies (Santa-Cruz, sc-369 and sc-356, respectively), or 5 μl of antidimethylhistone H3 (Lys9), anti-acetylhistone H3 (Lys9) (Upstate Biotechnology 07-212 and 06-942, respectively), or 5 μl of anti-NF1 or anti-C/EBPβ antibodies. Then, 10 μl of protein A-agarose solution was added for an additional 2 h.

The protein A-agarose beads were pelleted with the immunoprecipitate for 20 s at 1,500 × g and washed four times with 800 μl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 140 mM NaC1, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, once with 800 μl of LiCl buffer containing 0.25 M LiC1, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), and twice with 800 μl of TE containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 1 mM EDTA. The immune complexes were eluted by adding 500 μl of elution buffer (1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1 M NaHCO3, 200 mM NaCl). The cross-link was reversed at 65°C overnight. After 1 h of incubation at 45°C with a PK solution (10 μl of 0.5 M EDTA, 20 μl of 1 M Tris-HCl [pH 6.5], and 20 μg of proteinase K), DNA was extracted by phenol-CHCl3, ethanol precipitated, resuspended in 80 μl of TE, and stored at 4°C.

PCR were performed with real-time quantitative PCR (ABI Prism 7700 sequence detection system, Perkin Elmer) with SYBR Green. Primers were designed with Primer Express 1.5 software. The following primers were used: −0.007 region (promoter): upper strand, CAAAGGGCGTTTTTGACAACTG; lower strand, TCTCTTGCACCTGCCTCTTCTAA; −1.545 region: upper strand, TGTGAAAAGCTGGCCTCCTAA; lower strand, GGGAACTGCAGACACTTCAGAAA; −2.38 region: upper strand, CATAGGGATAATAAATCTAAGTTTGGACAA; lower strand, CTATCCAGTAGAGGTCTCAATCAT; −2.54 region (−2.7-kb enhancer): upper strand, CTGTTTGACCACCATGGAGTCA; lower strand, TCCGCTAACTCTGCTTTGC; −3.289 region: upper strand, CAGCCCATCAGAAGGATCATC; lower strand, GCATCAGTCGCCAAAGGT; −3.847 region (−3.9-kb enhancer): upper strand, TTGCTGGGATTTCCACAGTGT; lower strand, TCGTGATGGGCAGCTGG; −4.770 region: upper strand, TCTAGGCCCATTCCAACAGTTC; lower strand, TTTGTAAGGCCCCACTGAAGTA; −5 604 region: upper strand, TCTATGACAATTCACATCCAACACA; lower strand, AACGTAAAGCAGAAGACCCTCTTCA; −6.066 region (−6.1-kb enhancer): upper strand, GGTTGGGGTATTACCGAGGAA; lower strand, TTTGTTTTTGACAGCTTGCAG; −7.156 region: upper strand, CGCTGCTCTCAAGTTTGTGTCT; lower strand, AACTGCGGCCAACATCTTT; −10.07 region: upper strand, CCCTATTCAACCATGTAATGTA; lower strand, ACAAGAGGGTGAGGCCAAGT; and β-actin coding region: upper strand, TGTCCACCTTCCAGCAGTGT; lower strand, AGTCCGGTTTAGAAGCATTTGC.

The names of the lysozyme locus-specific primers correspond to their distance in kilobases from the transcription start site. Amounts of DNA precipitated in each experiment were calculated by comparison with standard curve values obtained from amplification reactions carried out with serial dilutions of chicken genomic DNA. To control the specificity of the amplification reaction and to make sure that only one product was generated, products were examined with a dissociation curve program (Dissociation Curves 1.0) and analyzed by gel electrophoresis. Relative PCR signals for all primers were first calculated as a signal ratio obtained with the specific antibody versus signals observed with the IgG control (nonspecific background). In order to correct for the efficiency of chromatin immunoprecipitation in different experiments, signals were then normalized to those obtained with the −10.07 primer.

For H3 acetylation mapping experiments, signals were normalized to β-actin acetylation levels. The signal ratio −10.07-kb primer/β-actin primer was always constant between experiments carried out with different cell types (data not shown). This showed that no differences in acetylation and methylation levels were observed at −10.07 kb and no binding of any of the trans-activating factors assayed in this study occurred.

DNA modification with bisulfite and PCR amplification.

Bisulfite treatment converts cytosine but not 5-methylcytosine into uracil and was performed exactly as published previously (62). Primers were designed to be complementary to the upper and lower strands after modification. Primer sequences are available on request. PCR products were sequenced, and signals corresponding to T and unmodified C nucleotides were analyzed and quantified with a CEQ 8000 sequencer (Beckman Coulter).

RESULTS

In unstimulated macrophages, all lysozyme gene enhancers form stable transcription factor complexes.

In this study we analyzed developmental changes that occur in the recruitment of transcription factors and chromatin remodeling activities to the chicken lysozyme locus. To this end, we employed retrovirally transformed myeloid cell lines resembling multipotent progenitor cells (HD50 MEP), macrophages (HD11), and erythroblasts (HD37) (summarized in Fig. 1). These cell lines were originally derived from transformed hematopoietic cell clones infected with different retroviruses (6, 23, 50) and have been a highly valuable tool for the examination of the influence of chromatin structure on the developmental control of gene expression (10, 38). Of the three cell lines, only the HD11 cells express the lysozyme gene and display DNase I-hypersensitive site at the enhancers and the promoter (30, 38). HD11 cells can be further differentiated by LPS treatment, which leads to growth cessation and distinct morphological changes.

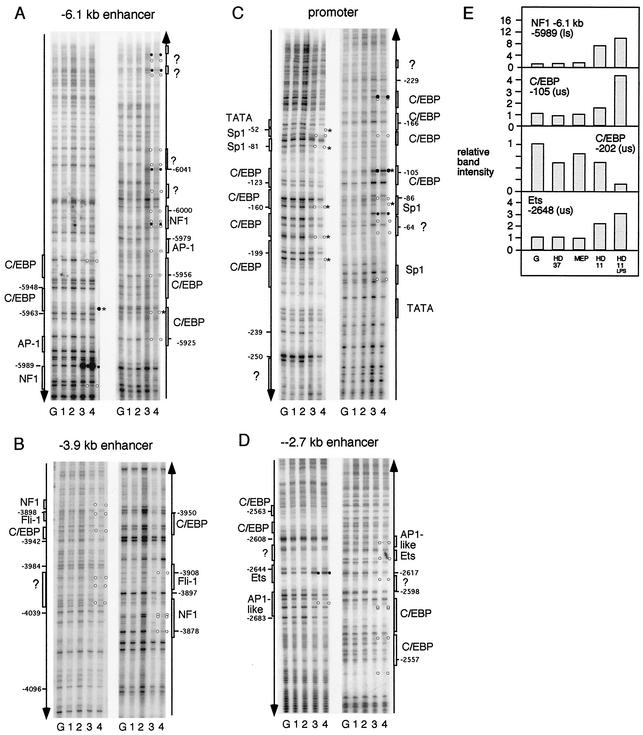

To examine DNA-protein interactions in vivo, we employed DMS methylation protection assays, which reveal purine (mostly G[N7]) contacts between proteins and DNA inside cells. To visualize regions of enhanced or suppressed DMS reactivity, we used a recently refined ligation-mediated PCR technique that is of high sensitivity and produces longer reaction products (60) than previous methods (38). Figure 2 depicts in vivo DMS footprinting experiments showing binding of the different factors to the early enhancers at −6.1 kb (Fig. 2A) and −3.9 kb (Fig. 2B), the promoter (Fig. 2 C), and the late-acting −2.7-kb enhancer (Fig. 2D) in the different cell lines. These experiments confirm that there was no trace of any alteration of DMS reactivity in HD50 MEP precursor cells compared to HD37 erythroid cells and naked DNA. Only HD11 monocyte/macrophage cells displayed in vivo footprints indicating the formation of stable transcription factor complexes over known consensus sequences for transcription factors such as NF1, Ets, AP-1-like, Sp1, and C/EBP.

FIG. 2.

In vivo DMS footprinting of the early enhancers at −6.1 kb (A) and −3.9 kb (B), the promoter (C), and the −2.7-kb enhancer (D) in the different cell lines. The positions of known transcription factor binding sites and their natures are indicated as white boxes at the left (lower strand) or the right (upper strand). Alterations in G(N7) reactivity are indicated as white (protection) or black (enhancement) circles. Only alterations that were seen in more than one experiment are highlighted. Asterisks indicate LPS-responsive alterations. Lane G, naked DNA; lane 1, HD37; lane 2, HD50 MEP; lane 3, HD11; lane 4, HD11 plus LPS. (E) Quantification of relative band intensity at selected transcription factor binding sites in different cell types as indicated and naked DNA (G). (us), upper strand; (ls), lower strand. Please note that we recently completed the sequence of the entire lysozyme locus and that the coordinates have been revised from previous publications.

Interestingly, our results show that, similar to what we observed with the early enhancers, transcription factor occupancy at the −2.7-kb enhancer was apparently complete even without LPS stimulation (Fig. 2D and E). However, we have previously established that the chromatin at the −2.7-kb enhancer is only fully remodeled after LPS treatment, and this holds true for nucleosome remodeling as well as DNase I-hypersensitive site formation (30, 31). This finding is interesting in light of the fact that the −2.7-kb enhancer is one nucleosome away from the −2.4-kb silencer, which contains a CTCF site (4, 31).

In the β-globin locus, CTCF has been shown to block enhancer action (5). In the lysozyme locus, the silencer element represses the activity of the −2.7-kb enhancer in transient transfection assays (59). Our footprinting experiments therefore suggest that if CTCF blocks the activation of the enhancer in chromatin, it functions not via the inhibition of transcription factor binding but on the level of chromatin structure. Furthermore, it has been shown by others that CTCF can indeed recruit histone deacetylase activity (48). Preliminary chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments (P. Lefevre and C. Bonifer, unpublished observations) indeed indicate that the disappearance of the silencer DNase I-hypersensitive site and the appearance of the enhancer DNase I-hypersensitive site after LPS stimulation coincide with the departure of CTCF from its binding site.

All lysozyme enhancers are targets for Ets proteins in vivo.

Until now, the nature of the factors binding to the Ets consensus sequences at the lysozyme enhancers was not clear. We recently conducted a survey of the types of Ets proteins binding to lysozyme cis elements in electrophoretic mobility shift assays with nuclear extracts and specific antisera against Ets factors (unpublished data). These experiments identified Fli-1 as a protein binding to the −3.9-kb enhancer. Fli-1 is able to trans-activate constructs harboring any of the three lysozyme enhancer elements but not the promoter (data not shown). Our in vivo footprinting experiments demonstrate that the Ets consensus sequence at the late-acting −2.7-kb enhancer is occupied in HD11 cells (Ets site, Fig. 2D) but not in any other myeloid cell type tested. It was previously shown that this site is predominantly bound by PU.1 in vitro by electrophoresis mobility shift assays performed with HD11 nuclear extracts (1, 15). Within the −6.1-kb enhancer sequences tested in transfection assays, we found a consensus sequence for Fli-1 that overlaps the distal C/EBP site. However, using nuclear extracts and electrophoretic mobility shift assays, we were unable to see Fli-1 binding in vitro (data not shown).

To further investigate binding of Ets family proteins, we screened the 5′ regulatory region of the lysozyme locus by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays. We assayed the relative enrichment of precipitated DNA sequences by a real-time PCR assay with SYBR Green (22) and a collection of different primers recognizing all lysozyme cis-regulatory elements and sequences between the elements and far upstream. The primer at −10.07 kb corresponds to a sequence that has previously been shown to lie at the boundary of generally DNase I-sensitive and -resistant chromatin (34) and is far away from any DNase I-hypersensitive site. To additionally control the efficiency of precipitation and to normalize signals for different experiments and different cell types, we performed real-time PCR assays with primers corresponding to the coding region of the β-actin gene. For all transcription factor and cofactor chromatin immunoprecipitation assays in each of the cell type tested, the β-actin primer and the −10.07-kb primer gave the same signal (data not shown). All other signals were therefore normalized to this value.

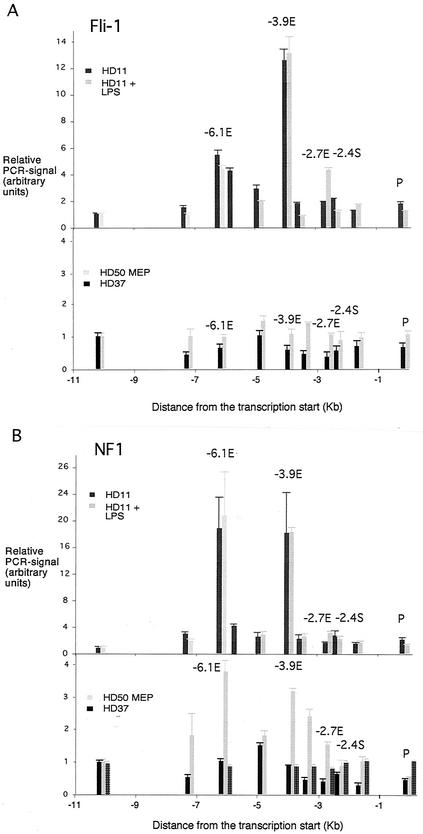

Our chromatin immunoprecipitation assays confirmed that the −6.1-kb and −3.9-kb enhancers were both targets of Fli-1 in vivo (Fig. 3A). However, because the binding site of Fli-1 at the −6.1-kb enhancer has yet to be defined, we are currently investigating whether cooperative interactions between different factors take place at the different enhancers. Interestingly, −2.7-kb enhancer sequences were only precipitated with the Fli-1 antibody in HD11 cells after treatment with LPS. Due to the unavailability of a chromatin immunoprecipitation-capable PU.1 antibody, we are at present unable to say whether the Ets consensus sequence in the −2.7-kb enhancer that binds PU.1 in vitro is also bound by PU.1 in vivo. It is possible, however that Fli-1 is recruited to the −2.7-kb enhancer and replaces PU.1 after LPS stimulation.

FIG. 3.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay examining transcription factor binding to the lysozyme 5′ regulatory region with antibodies against Fli-1 (A) or NF1 (B) in HD50 MEP, HD37, HD11, and LPS-treated HD11 cells. The relative enrichment was calculated by normalizing the PCR signals to that of the −10.07-kb primer and the β-actin control primer as described in the text. The hatched bars in the lower panel refer to a control experiment in HD50 MEP cells in which chromatin was not cross-linked. The data are plotted as mean value of at least two independent chromatin immunoprecipitation assays and three independent amplifications.

In multipotent progenitor cells, lysozyme chromatin is partially accessible to transcription factor binding and DNA is partially demethylated.

The −6.1-kb enhancer, the −3.9-kb enhancer, and the promoter are the first elements that are switched on during macrophage differentiation. The presence of the −6.1-kb enhancer is absolutely required for the correct timing of lysozyme locus activation (33). The binding sites for NF1 family members at the early enhancers at −6.1 kb and −3.9 kb are important for enhancer activity in transfection assays (24, 45). Our chromatin immunoprecipitation assays now provide final evidence for the involvement of the NF1 factor family in lysozyme regulation in vivo (Fig. 3B). In HD11 cells, both enhancer regions were precipitated by the NF1 antiserum, yielding an approximately 20-fold enrichment of enhancer sequences over background. These results, together with our in vivo footprinting data, clearly show that these proteins only gain stable access to lysozyme gene chromatin in lysozyme-expressing cells.

NF1 proteins are present and functionally active in all three cell types tested (45). Despite this fact, all NF1 binding detected by chromatin immunoprecipitation approached background levels in HD37 cells. In addition, although −6.1-kb and −3.9-kb enhancer sequences are significantly enriched for NF1 binding in HD11 cells in the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay, we did not see any evidence for coprecipitation of enhancer sequences with the promoter.

A surprising result of our chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments with the NF1 antibody was that we observed a low but highly reproducible three- to fourfold enrichment of NF1 proteins over the −6.1-kb and −3.9-kb enhancers in HD50 MEP cells even in the absence of in vivo footprints (Fig. 3B). Control experiments with non-cross-linked samples from HD50 MEP cells proved that this was not an artifact of the immunoprecipitation reaction (Fig. 3B). This indicates that, in contrast to HD37 erythroblasts, the chromatin in precursor cells is to a certain extent accessible to NF1 binding and that the protein gets trapped by the cross-linking agent. However, this is not a stable interaction, since it was not sufficient to protect DNA from being methylated by DMS. NF1 binding resulted in a very strong DMS hyperreactivity at a guanine at bp −5988 (Fig. 2A), which would have been visible if NF1 were stably bound to its recognition sequence in a subset of as little as 5% of all cells.

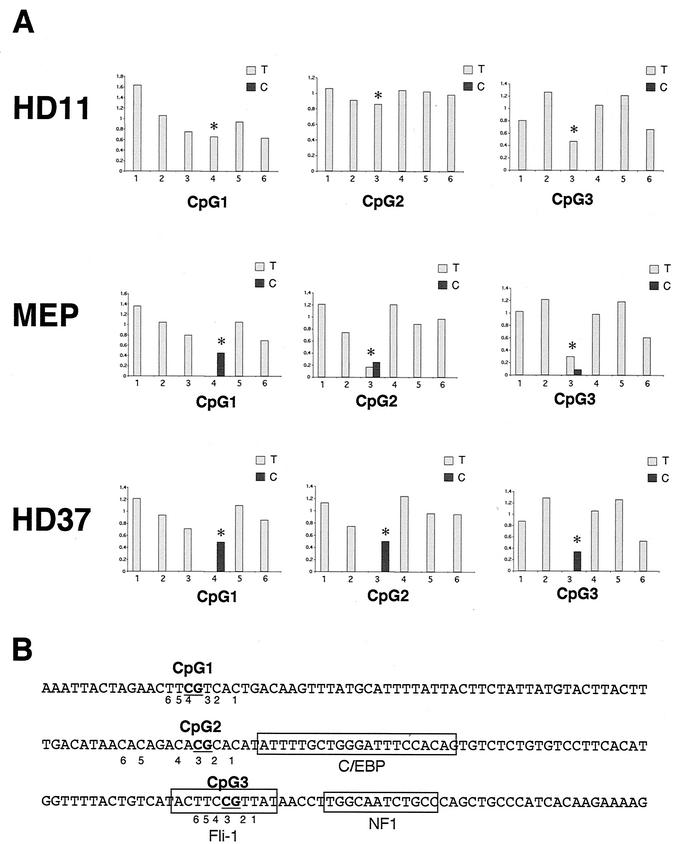

A hallmark of genes that are irreversibly epigenetically silenced is DNA methylation at CpGs. DNA methylation is closely associated with the organization of chromatin into tightly packed heterochromatin (7). One explanation for the partial accessibility of chromatin in the lysozyme 5′ gene regulatory region in multipotent progenitor cells was therefore that the chromatin in HD50 MEP precursor cells was already modified and poised for activation. We therefore examined the state of CpG methylation at different positions of the lysozyme locus by bisulfite sequencing. We chose an approach that would allow us to quantitatively determine the proportion of methylated and nonmethylated CpGs within a given cell population. The bisulfite reaction converts nonmethylated cytosines into uracil (read as a T), whereas methylated cytosines remain unmodified.

Figure 4 shows selected data for T and C bases from sequencing reactions performed on PCR fragments amplified from bisulfite-treated DNA where we examined three CpGs around the −3.9-kb enhancer. CpG3 (Fig. 4A) was part of the Fli-1 consensus sequence (Fig. 4D), CpG2 (Fig. 4B) was just upstream of the C/EBP binding site, and CpG1 was outside of the enhancer core. In lysozyme-nonexpressing HD37 erythroblast cells, all CpGs were methylated and stayed C's (black bars), whereas in HD11 cells all CpGs were demethylated and converted into U's (grey bars). In HD50 MEP progenitor cells, the situation was more complex. At the Fli-1 binding site, only some CpGs were demethylated, and the same held true for CpG2, whereas CpG3 appeared to be fully methylated. Amplification of the other strand confirmed these results (data not shown). These results add increasing evidence to the idea that lysozyme chromatin in multipotent progenitors is already partly remodeled towards an active conformation.

FIG. 4.

DNA methylation at the −3.9-kb enhancer. Genomic DNA from the indicated cell lines was subjected to bisulfite modification and analyzed by bulk sequencing as described in the text. (A) Peaks from a sequencing reaction indicating cytosines and thymines at CpGs 1, 2, and 3 were quantified and are displayed as black and grey bars, respectively. Differentially modified C's that are part of a CpG are indicated by an asterisk. (B) Sequence of the 5′ part of the 3.9-kb enhancer indicating the positions of T's (not modified) or C's (modified) or the central CpG that contains a C which is differentially modified. The positions of CpGs 1 to 3 and of the transcription factor binding sites are indicated.

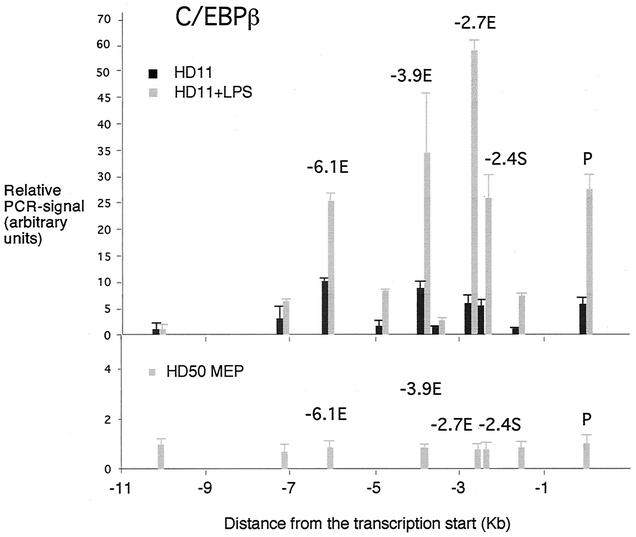

LPS induction of HD11 cells leads to a dramatic difference in C/EBPβ binding at all enhancer elements of the chicken lysozyme locus and the promoter in vivo.

The −6.1-kb enhancer, the −2.7-kb enhancer, and the promoter have been shown to respond to LPS treatment in transient transfection assays (15, 20, 42). LPS responsiveness of these elements is mediated by consensus binding sites for C/EBP (15, 20). C/EBP proteins, in particular C/EBPβ, are important factors for the regulation of inflammatory response genes and are involved in the regulation of a number of these genes in myeloid cells (54, 61). Of the three cell types tested here, C/EBPβ (or NF-M) was only expressed in HD11 cells (45).

We therefore measured changes in DMS reactivity in the −6.1-kb enhancer, the −2.7-kb enhancer, and the promoter by quantifying ligation-mediated PCR-generated bands from unstimulated and LPS-treated HD11 cells (Fig. 2A, C, and D) on a phosphorimager. An example of such an analysis is shown in Fig. 2E. In the early enhancers, consensus sequences for factors such as NF1, AP-1, and Fli-1 were fully occupied with or without LPS stimulation. In contrast, one binding site for C/EBP factors in the −6.1-kb enhancer and most of the C/EBP and Sp1 sites in the promoter were only fully occupied after LPS treatment (Fig. 2). This confirms the involvement of these factors in LPS-induced gene transcription (12). The −2.7-kb enhancer element only forms a strong DNase I-hypersensitive site after LPS treatment, but the transcription factors responsible for chromatin remodeling in LPS-simulated cells had not previously been characterized. It came as a surprise that we were unable to see any difference in transcription factor occupancy detected by in vivo footprinting between unstimulated and LPS-induced cells. The Ets consensus sequence bound by PU.1 was almost fully occupied in both cell types, and we could not see any difference in occupancy at the AP1 and C/EBP consensus sequences.

These experiments were complemented by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 3 and 5). In chromatin immunoprecipitation assays with an antibody specific for C/EBPβ, we observed a five- to ninefold enrichment of enhancer and promoter sequences in unstimulated HD11 cells compared to HD50 MEPs (Fig. 5). In LPS-stimulated HD11 cells, NF1 and Fli-1 binding was unchanged, whereas a dramatic 25- to 60-fold increase in the C/EBPβ signal at all cis-regulatory elements was observed. The biggest relative increase was seen at the −2.4-kb silencer/−2.7-kb enhancer region, which harbors a functional LPS-responsive C/EBP site (15). Taken together, these results indicated that LPS treatment not only activated the late-acting −2.7-kb enhancer but also led to a change in the conformation of transcription factor complexes at the early enhancers and the promoter. Preliminary experiments with LPS-stimulated HD11 cells indicate that at least one of the Sp1 consensus sequences at the promoter is recognized by Sp1 itself (P. Lefevre and C. Bonifer, unpublished observation). This confirms earlier in vitro binding studies (3).

FIG. 5.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay examining transcription factor binding to the lysozyme 5′ regulatory region with antibodies against C/EBPβ (NF-M) in HD50 MEP, HD11, and LPS-treated HD11 cells as indicated. The relative enrichment was calculated by normalizing the PCR signals to that of the −10.07-kb primer and the β-actin control primer as described in the text. The data are plotted as mean value of at least two independent chromatin immunoprecipitation assays and three independent amplifications.

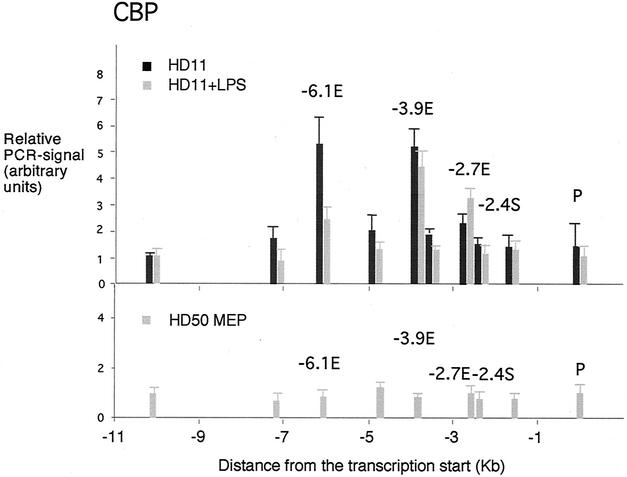

CBP is recruited only to lysozyme enhancers.

One of the consequences of the formation of active enhancer and promoter complexes is the recruitment of chromatin modification activities such as histone acetyltransferase complexes. Of the factors involved in lysozyme gene regulation, NF1, Fli-1, Sp1, and C/EBP have all been shown to interact with the histone acetyltransferase CBP (43, 44, 51). We therefore assayed the distribution of CBP across the 5′ regulatory region (Fig. 6). No interaction of CBP could be observed in HD50 MEP cells. In unstimulated HD11 cells, we found a three- to fivefold increase of CBP binding over background over the enhancers. After LPS stimulation, no increase in CBP recruitment was seen over the early enhancers. On the contrary, CBP association at the −6.1-kb enhancer went down upon stimulation. In the −2.7-kb enhancer region we saw a slight but reproducible increase. Although strongly bound by C/EBP proteins, no CBP was bound at the promoter with or without LPS treatment.

FIG. 6.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay examining transcription factor binding to the lysozyme 5′ regulatory region with antibodies against CBP in HD50 MEP, HD11 and LPS-treated HD11 cells as indicated. The relative enrichment was calculated by normalizing the PCR signals to that of the −10.07 kb primer and the β-actin control primer as described in the text. The data are plotted as mean value of at least two independent chromatin immunoprecipitation assays and three independent amplifications.

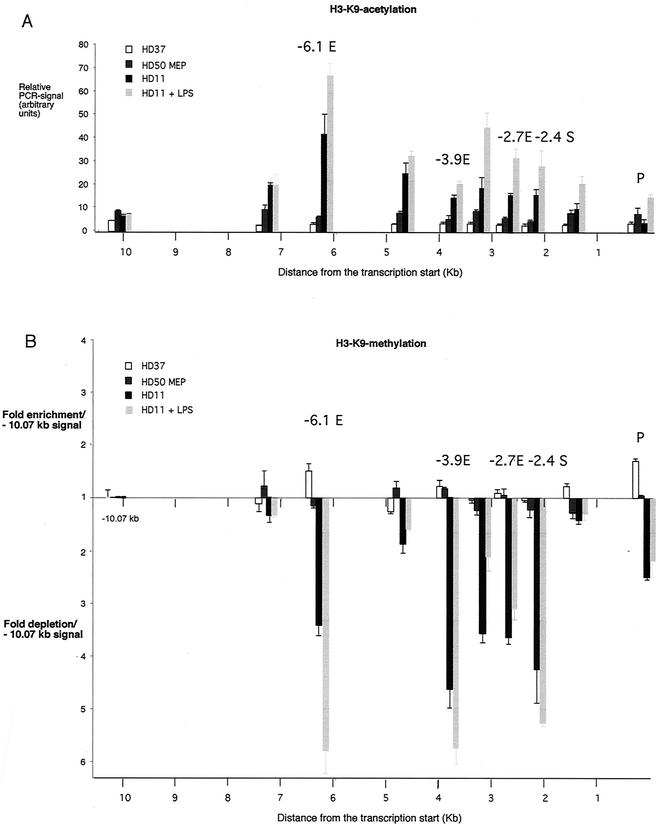

Inverse correlation between histone H3K9 acetylation and methylation at the lysozyme cis-regulatory elements.

A consequence of the recruitment of chromatin-modifying activities to the genome is the differential modification of histones. Histones carry distinct modifications such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation at specific amino acids of their N-terminal tails, which constitute a histone code that is read by specific proteins (35). Experiments examining the chicken β-globin locus have found strict correlations with expression levels and changes in histone acetylation and methylation during erythroid differentiation, with primary cells and retrovirally transformed chicken cell lines similar to the ones used in this study (28, 46, 47). In order to get first insights into the dynamics of histone modifications at low resolution, we assayed lysozyme chromatin in the different cell lines by chromatin immunoprecipitation with antibodies against acetylated and methylated lysine 9 of histone H3 (Fig. 7). These modifications are mutually exclusive, whereby methylation is a hallmark of inactive chromatin and acetylation is found at active loci (for recent reviews, see references 14 and 39).

FIG. 7.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay examining the histone H3 modification status in HD37, HD50 MEP, HD11, and LPS-treated HD11 cells as indicated. (A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay with antibodies recognizing histone H3 lysine 9 acetylation. The relative enrichment was calculated by normalizing the PCR signals to that of a β-actin control primer as described in the text. Note therefore that the ratio of β-actin to −10.07-kb signal intensity is constant. (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay with antibodies recognizing methylated histone H3 lysine 9. In this case the relative enrichment or depletion was calculated by normalizing the PCR signals to that of the −10.07-kb primer as described in the text. The levels of histone H3 methylation at the boundaries of the DNase I-sensitive domain at −10.07 kb in the different cell lines are the same, as determined by normalization to signals obtained with the β-actin primer. The β-actin primer yielded signals that were two- to threefold lower that those obtained with the −10.07-kb primer (data not shown). The data are plotted as mean value of at least two independent chromatin immunoprecipitation assays and three independent amplifications.

Both HD37 cells and HD50 MEP cells showed a low level of histone H3 acetylation across the whole locus that was similar to that seen in the −10.07-kb region (Fig. 7A). In HD11 cells, the histone acetylation levels at the −10.07-kb region were also low. This indicates that, similar to what has been observed with the chicken β-globin locus, the boundary of general DNase I sensitivity coincides with the boundary of histone acetylation, providing a second example for this phenomenon (28, 34). In HD11 cells we observed a high level of acetylation around the enhancers, but acetylation levels at the promoter were as low as in lysozyme-nonexpressing cells. With respect to this feature, the distribution of hyperacetylated histones was similar to the distribution of recruited CBP (Fig. 6). We observed identical results with antibodies against mono- and diacetylated (K9/K14) histone H3 (data not shown).

The distribution of methylated H3 showed the opposite pattern from that seen for acetylated H3 (Fig. 7B). HD37 and HD50 MEP did not show any significant differences in methylation level. H3 methylation levels appeared to be uniform across the locus except for the −6.1-kb enhancer and the promoter, where they were slightly but reproducibly higher in HD37 compared to HD50 MEP. In HD11 cells we observed a general histone H3 demethylation across the 5′ regulatory region. This specific demethylation was most prominent at the enhancers and the promoter.

DISCUSSION

Initial activation of the lysozyme locus during macrophage differentiation involves the recruitment of NF1, Fli-1, and CBP.

We have shown previously that the early enhancers and the promoter are activated first at the CFU-GM stage and stay active during macrophage differentiation (30, 33). Here we present direct evidence that the −6.1-kb and −3.9-kb enhancers are targets for the Ets factor Fli-1 and members of the NF1 family. The activation of the −6.1-kb and −3.9-kb enhancers in myeloid precursor cells is in concordance with the finding that NF1 is ubiquitously expressed (25), and Fli-1 has been found to be expressed in the earliest hematopoietic precursor cells (65). Judging from transient transfection and DNase I fine mapping data, the factors including and surrounding the NF1 sites constitute the essential core in both enhancer elements (24, 45, 57). It is therefore tempting to speculate that these two factors are crucial for CFU-GM-specific enhancer activation in a chromatin context, similar to what has been found with the stem cell factor enhancer (22) (see also below).

Functional experiments in transgenic mice as well as chromatin structure studies have shown that in contrast to the early enhancers and in the presence of the −2.4-kb silencer, the −2.7-kb enhancer is activated only late in myelopoiesis (30, 33). Transfection experiments in HD11 cells with constructs containing both elements show no enhancer activity, whereas the −2.7-kb enhancer on its own is active in these cells, indicating that the −2.4-kb element represses the activity of the enhancer (59). As the −2.7-kb enhancer core is fully occupied in HD11 cells, which represent a rather late developmental stage in myelopoiesis, it will be interesting to see whether the differential developmental regulation of this element is entirely caused by the activity of the silencer or displays an intrinsically different timing of activation.

One of the functions of enhancer complexes is to recruit chromatin modification factors to specific genes (reviewed in reference 19). Our data demonstrate that all lysozyme enhancers interact with the CBP-histone acetyltransferase complex. We have not yet been able to identify any other histone acetyltransferase complex acting on the lysozyme locus. A number of transcription factors binding to the lysozyme enhancers are able to recruit CBP. In this context, it is interesting that the central NF1/Fli-1 sites in the −3.9-kb enhancer are essential for stimulation of enhancer activity by trichostatin A in transient transfection assays (45). Whether this also holds true for the −6.1-kb enhancer is presently not known. However, it appears to be an interesting possibility, which would lend significance to the fact that only the two early-acting enhancers employ NF1/Fli-1.

The recruitment of CBP parallels the increase of histone H3 acetylation over all lysozyme enhancers in HD11 cells, suggesting that this histone acetyltransferase is responsible for the high level of acetylation in these elements. The low resolution of our chromatin immunoprecipitation assays of approximately 500 bp presently does not permit us to obtain information about specific nucleosomes that are modified by CBP. To answer this question, more elaborate experiments mapping acetylated histones across the chicken lysozyme chromatin domain at nucleosome resolution are under way (F. Myers, P. Lefevre, C. Bonifer, A. Thorne, and C. Crane-Robinson, unpublished data).

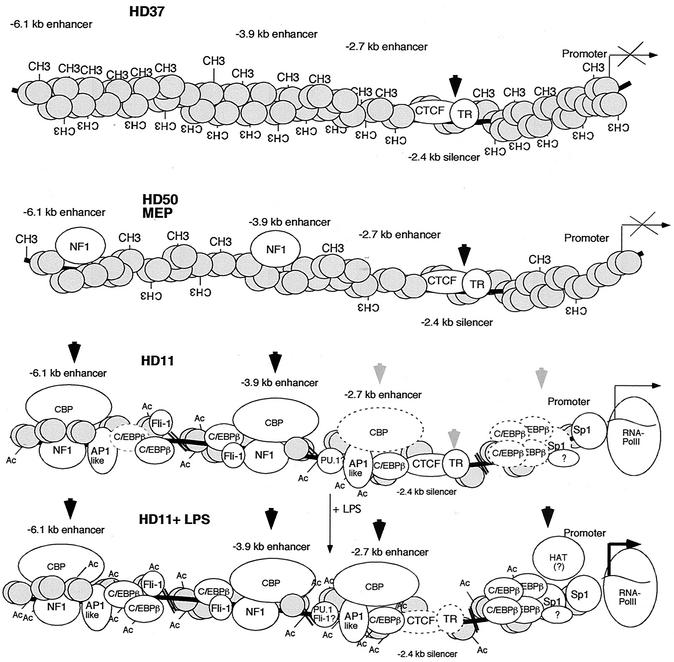

LPS stimulation leads to reorganization of transcription factor complexes at enhancers and promoter without an additional recruitment of CBP.

LPS-induced HD11 cells represent the terminal macrophage differentiation state. Figure 8 summarizes the events taking place during LPS stimulation of HD11 cells. Our chromatin immunoprecipitation and in vivo footprinting data clearly demonstrate no change in binding of the Ets factor Fli-1 and members of the NF1 family to the enhancers at −6.1 kb and −3.9 kb as a result of LPS stimulation of HD11 cells. However, in this study we present clear evidence for a significant reorganization of the chromatin of all lysozyme enhancer elements and the promoter after LPS treatment (Fig. 7).

FIG. 8.

Different steps in lysozyme locus activation. Summary of changes in chromatin structure, transcription factor occupancy, and cofactor recruitment in the chicken lysozyme 5′ regulatory region in HD37 erythroblasts, HD50 MEP precursor cells, as well as unstimulated and LPS-stimulated HD11 cells (not to scale). White shapes represent transcription factors binding to the enhancer cores, the promoter, and the −2.4-kb silencer. TR, thyroid hormone receptor, binding to the −2.4-kb silencer next to the CTCF site (4). Methyl groups (CH3) indicate DNA methylation, and acetyl groups (Ac) indicate histone acetylation. Grey circles represent nucleosomes. Shapes with dashed lines indicate transcription factor complexes which are not present in every cell or become stabilized after LPS stimulation. Black vertical arrows indicate strong DNase I-hypersensitive sites, and grey arrows indicate weak DNase I-hypersensitive sites.

All cis regulatory elements displayed an increased C/EBP signal in the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay, and all displayed an increase in histone H3 acetylation. At the enhancers the situation appears to be complex, since, as judged by in vivo footprinting, only one C/EBP site at the −6.1-kb enhancer displayed a change in transcription factor occupancy upon stimulation. It is therefore possible that C/EBP may already be recruited at some sites, but binding becomes stabilized after LPS treatment and therefore is more efficiently cross-linked. In support of this, it was shown that C/EBP responds to LPS stimulation by an increased DNA binding activity (36, 40). In addition, although histone acetylation levels were increased, no enhanced recruitment of CBP was observed. This finding can be explained by the fact that LPS stimulated HD11 cells stop growing, suggesting that already recruited CBP acts upon already partially acetylated histones. In addition, CBP itself has been shown to respond to LPS stimulation with an enhanced activity (66) and may synergistically interact with already recruited, but stimulated C/EBP to upregulate lysozyme transcription. CBP may even leave the enhancer complex when histones are fully acetylated in growth arrested cells, as suggested by the decrease in CBP association at the −6.1-kb enhancer.

In contrast to the enhancers, at the promoter the enhanced level of transcription paralleled increased occupancy of Sp1 and C/EBP binding sites, thus adding weight to earlier DNase I-hypersensitive site mapping experiment that showed increased DNase I accessibility after LPS stimulation (30).

A surprising finding was the lack of recruitment of CBP and the low level of H3 acetylation at the lysozyme promoter in HD11 cells, even in the LPS induced state. This distinguishes the lysozyme locus from gene loci such as the β-globin loci in which overall acetylation levels at the promoters are high (16, 46), although CBP recruitment in these systems have not been examined. In addition, although the lysozyme promoter is required to remodel chromatin at the early enhancers (32), we do not see any evidence for a stable interaction between lysozyme enhancers and the promoter. In our experiments, promoter sequences are not precipitated with anti-NF1 antibodies. This is in contrast to studies that recently demonstrated such interactions in the beta-globin locus and the HNF-4 gene (13, 27, 64). However, in contrast to these genes, which are mostly developmentally regulated, the lysozyme gene is highly inducible. It is possible that enhancer-promoter interaction occurs in a transient fashion and histone acetylation at the promoter is restricted to a few specific nucleosomes and/or is transient as described with other inducible gene systems (reference 63 and references therein).

In addition, as shown with the 32 α1 antitrypsin promoter, the assembly of a subset of activator proteins and basal transcription factors can occur independent of specific histone hyperacetylation and on nucleosomal DNA (58). In this case, the onset of transcription was dependent on the recruitment of the SWI/SNF type chromatin remodeling complex hBrm leading to the remodeling of one specific nucleosome and the recruitment of the full basal transcription machinery. What makes this observation relevant to LPS-inducible transcription exemplified by the lysozyme locus, is the observation that overexpression of C/EBPβ is able to activate the chicken lysozyme locus from the silent state via recruitment of SWI/SNF-type chromatin-remodeling activities (41). The lysozyme promoter is organized in specifically positioned nucleosomes in lysozyme-nonexpressing cells, which become remodeled after transcriptional activation (31). It is therefore possible that the recruitment of C/EPBβ to the lysozyme promoter after LPS stimulation is involved in this remodeling process and the subsequent activation of transcription. Experiments are under way to investigate the timing of these complex processes in more detail.

Lysozyme gene chromatin in myeloid precursor cell lines is primed for activation and presents a target for the transient binding of NF1 proteins.

We have recently demonstrated that the chromatin of the lysozyme locus in myeloid precursor cell lines, although devoid of stably bound transcription factors, is already remodeled towards the active state and differs from that in nonmyeloid cells (38). Our histone methylation studies show subtle, but reproducible differences between the lysozyme nonexpressing cells HD50 MEP and HD37. HD50 MEP precursor cells display a uniform histone H3 (K9) methylation level across the locus, whereas HD37 histone H3 (K9) methylation levels are up to two-fold higher compared to HD50 MEP at the −6.1-kb enhancer and the promoter. For reasons of resolution, we presently do not know whether this indicates the methylation of specific nucleosomes. In HD11 cells, histone H3 (K9) methylation levels over the cis-regulatory elements are dramatically reduced compared to sequences outside of the domain of general DNase I sensitivity, where histone H3 (K9) methylation levels are similar between cell lines.

Our DNA methylation studies are more conclusive, and Fig. 8 summarizes our current model of the situation in precursor cells. In HD50 MEP cells we see a clear demethylation of specific CpGs near the enhancer core, but not outside. This suggests a targeted inhibition of methyl-transferase recruitment by specific transcription factors, most likely during DNA replication. That this may indeed be true is suggested by our finding of a transient/unstable binding of NF1 to lysozyme chromatin in HD50 MEP cells, but not HD37 cells. At first sight, this presented a paradox, since NF1 has always been regarded as a transcription factor that is unable to access its binding site if it is organized in a nucleosome (8, 56). However, the trans-activation domain of NF1 has been shown to bind to histone H3 (2) and histone interaction is required for the stimulation of simian virus 40 replication in vivo (53). This interaction does not require the N-terminal tails of histone H3 and occurs even when the latter is organized in a nucleosome. This indicates that NF1 is capable of performing certain functions on a nucleosomal template. It may transiently interact with DNA containing either the full palindromic consensus sequence that binds NF1 as stable dimer or half-sites occurring more frequently.

In HD50 MEPs, this interaction is not stable enough to lead to the assembly of a stable factor complex, as indicated by our in vivo footprinting results, but it may be stable enough to temporarily recruit transcription factor complexes to DNA which could leave a remodeled chromatin structure behind. Whether this is true also for Fli-1 is currently unknown; however, we could show that Fli-1 cannot bind to the −3.9-kb enhancer in vitro when the central CpG is methylated (data not shown). That HD50 MEP cells have the potential to form functional transcription factor complexes on lysozyme elements was confirmed by recent transient transfection experiments characterizing the -3.9-kb enhancer, which is active in HD11 cells and inactive in HD50 MEP and HD37 cells (45). Although no activation of the endogenous gene was observed, trichostatin A treatment activated this enhancer in HD50 MEP cells but not in HD37 cells.

As judged from our DNA methylation studies, in HD37 cells, lysozyme gene chromatin is epigenetically silenced, thus excluding the transient interaction of ubiquitously present transcription factors. Present technical limitations of the chromatin immunoprecipitation assay do not allow confirmation of these hypotheses in rare primary cells. However, our data support the idea that the chromatin structure of lineage-specific genes in progenitor cells is partially accessible and allows transcription factors to transiently bind and alter chromatin structure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Cockerill and George Follows for comments on the manuscript. P.L thanks Thierry Grange, Valerie Orlando, and the team from the EMBO course on DNA-Protein Interaction in vivo for their expert training in chromatin immunoprecipitation technology. We also thank Achim Leutz and Elisabeth Kowentz-Leutz for anti-C/EBPβ (NF-M) antibodies and Naoko Tanese for anti-NF1 antibodies.

Research in C. Bonifer's laboratory is supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust, the BBSRC, the Leukemia Research Fund, and the City of Hope Medical Centre. Nicola Wilson is a recipient of a Leukemia Research Fund summer studentship grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahne, B., and W. H. Strätling. 1994. Characterization of a myeloid-specific enhancer of the chicken lysozyme gene. J. Biol. Chem. 269:17794-17801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alevizopoulos, A., Y. Dusserre, M. Tsai-Pflugfelder, T. von der Weid, W. Wahli, and N. Mermod. 1995. A proline-rich TGF-beta-responsive transcriptional activator interacts with histone H3. Genes Dev. 9:3051-3066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschmied, J., M. Müller, S. Baniahmad, S. Steiner, and R. Renkawitz. 1989. Cooperative interaction of chicken lysozyme enhancer subdomains partially overlapping with a steroid receptor binding site. Nucleic Acids Res. 17:4975-4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baniahmad, A., C. Steiner, A. C. Kohne, and R. Renkawitz. 1990. Modular structure of a chicken lysozyme silencer: involvement of an unusual thyroid hormone receptor binding site. Cell 61:505-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bell, A. C., A. G. West, and G. Felsenfeld. 1999. The protein CTCF is required for the enhancer blocking activity of vertebrate insulators. Cell 98:387-396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beug, H., A. V. Kirchbach, G. Döderlein, J.-F. Conscience, and T. Graf. 1979. Chicken hematopoietic cells transformed by seven strains of defective avian leukemia viruses display three distinct phenotypes of differentiation. Cell 18:375-390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bird, A. 2002. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 16:6-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blomquist, P., Q. Li, and O. Wrange. 1996. The affinity of nuclear factor I for its DNA site is drastically reduced by nucleosome organization irrespective of its rotational or translational position. J. Biol. Chem. 271:153-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonifer, C., F. Bosch, N. Faust, A. Schuhmann, and A. E. Sippel. 1994. Evolution of gene regulation as revealed by differential regulation of the chicken lysozyme transgene and the endogenous mouse lysozyme gene in mouse macrophages. Eur. J. Biochem. 226:227-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonifer, C., U. Jägle, and M. C. Huber. 1997. The chicken lysozyme locus as a paradigm for the complex regulation of eucaryotic gene loci. J. Biol. Chem. 272:26075-26078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borgmeyer, U., J. Nowock, and A. E. Sippel. 1984. The TGGCA-binding protein: a eukaryotic nuclear protein recognizing a symmetrical sequence in double stranded linear DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 12:4295-4311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brightbill, H. D., S. E. Plevy, R. L. Modlin, and S. T. Smale. 2000. A prominent role for Sp1 during lipopolysaccharide-mediated induction of the IL-10 promoter in macrophages. J. Immunol. 164:1940-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter, D., L. Chakalova, C. S. Osborne, Y. F. Dai, and P. Fraser. 2002. Long-range chromatin regulatory interactions in vivo. Nat. Genet. 32:623-626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eberharter, A., and P. B. Becker. 2002. Histone acetylation: a switch between repressive and permissive chromatin: second in review series on chromatin dynamics EMBO Rep. 3:224-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faust, N., C. Bonifer, and A. E. Sippel. 2000. Differential activity of the −2.7 kb chicken lysozyme enhancer in macrophages of different ontogenic origins is regulated by C/EBP and PU.1 transcription factors. DNA Cell Biol. 18:631-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsberg, E. C., K. M. Downs, H. M. Christensen, H. Im, P. A. Nuzzi, and E. H. Bresnick. 2000. Developmentally dynamic histone acetylation pattern of a tissue-specific chromatin domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:14494-14499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritton, H. P., T. Igo-Kemenes, J. Nowock, U. Strech-Jurk, M. Theisen, and A. E. Sippel. 1984. Alternative sets of DNase I-hypersensitive sites characterize the various functional states of the chicken lysozyme gene. Nature 311:163-165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fritton, H. P., T. Igo-Kemenes, J. Nowock, U. Strech-Jurk, M. Theisen, and A. E. Sippel. 1987. DNase I-hypersensitive sites in the chromatin structure of the lysozyme gene in steroid hormone target and non-target cells. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 368:111-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fry, C. J., and C. L. Peterson. 2001. Chromatin remodeling enzymes: who's on first? Curr. Biol. 11:R185-R187. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Goethe, R., and L. Phi-van. 1994. The far upstream chicken lysozyme enhancer at −6.1 kilobase, by interacting with NF-M, mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced expression of the chicken lysozyme gene in chicken myelomonocytic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 269:31302-31309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goethe, R., and L. Phi-van. 1998. Posttranscriptional lipopolysaccharide regulation of the lysozyme gene at processing of the primary transcript in myelomonocytic HD11 cells. J. Immunol. 160:4970-4978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Göttgens, B., A. Nastos, S. Kinston, S. Piltz, E. C. Delabesse, M. Stanley, M. J. Sanchez, A. Ciau-Uitz, R. Patient, and A. R. Green. 2002. Establishing the transcriptional programme for blood: the SCL stem cell enhancer is regulated by a multiprotein complex containing Ets and GATA factors. EMBO J. 21:3039-3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graf, T., K. McNagny, G. Brady, and J. Frampton. 1992. Chicken “erythroid” cells transformed by the gag-myb-ets-encoding E26 leukemia virus are multipotent. Cell 70:201-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grewal, T., M. Theisen, U. Borgmeyer, T. Grussenmeyer, R. A. W. Rupp, A. Stief, F. Qian, A. Hecht, and A. E. Sippel. 1992. The −6.1-kilobase chicken lysozyme enhancer is a multifactorial complex containing several cell type-specific elements. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:2339-2350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gronostajski, R. M. 2000. Roles of the NFI/CTF gene family in transcription and development. Gene 16:31-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gualdi, R., P. Bossard, M. Zheng, Y. Hamada, J. R. Coleman, and K. S. Zaret. 1996. Hepatic specification of the gut endoderm in vitro: cell signaling and transcriptional control. Genes Dev. 10:1670-1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatzis, P., and I. Talianidis. 2002. Dynamics of enhancer-promoter communication during differentiation-induced gene activation. Mol. Cell 10:1467-1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hebbes, T. R., A. L. Clayton, A. W. Thorne, and C. Crane-Robinson. 1994. Core histone hyperacetylation co-maps with generalized DNase I sensitivity in the chicken β-globin chromosomal domain. EMBO J. 13:1823-1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu, M., D. Krause, M. Greaves, S. Sharkis, M. Dexter, C. Heyworth. and T. Enver. 1997. Multilineage gene expression precedes commitment in the hemopoietic system. Genes Dev. 11:774-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huber, M. C., T. Graf, A. E. Sippel, and C. Bonifer. 1995. Dynamic changes in the chromatin of the chicken lysozyme gene domain during differentiation of multipotent progenitors to macrophages. DNA Cell Biol. 14:397-402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huber, M., G. Krüger, and C. Bonifer. 1996. Genomic position effects lead to an inefficient reorganization of nucleosomes in the 5′ regulatory region of the chicken lysozyme locus in transgenic mice. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:1443-1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huber, M. C., U. Jagle, G. Kruger, and C. Bonifer. 1997. The developmental activation of the chicken lysozyme locus in transgenic mice requires the interaction of a subset of enhancer elements with the promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:2992-3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jägle, U., A. M. Müller, H. Kohler, and C. Bonifer. 1997. Role of positive and negative cis-regulatory elements regions in the regulation of transcriptional activation of the lysozyme locus in developing macrophages of transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 272:5871-5879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jantzen, K., H. P. Fritton, and Igo- T. Kemenes. 1986. The DNase I sensitive domain of the chicken lysozyme gene spans 24 kb. Nucleic Acids Res. 14:6085-6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jenuwein, T., and C. D. Allis. 2001. Translating the histone code. Science 293:1074-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz, S., E. Kowenz-Leutz, C. Müller, K. Meese, S. A. Ness, and A. Leutz. 1993. The NF-M transcription factor is related to C/EBPβ and plays a role in signal transduction, differentiation and leukemogenesis of avian myelomonocytic cells. EMBO J. 12:1321-1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komura, J., and A. D. Riggs. 1998. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-dependent PCR, a new, more sensitive approach to genomic footprinting and adduct detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 26:1807-1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kontaraki, J., H. H. Chen, A. D. Riggs, and C. Bonifer. 2000. Chromatin fine structure profiles for a developmentally regulated gene locus: reorganization of chromatin structure of the lysozyme locus before trans-activator binding and activation of gene expression. Genes Dev. 14:2106-2122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kouzarides, T. 2002. Histone methylation in transcriptional control. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12:198-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kowenz-Leutz, E., G. Twamley, S. Ansieau, and A. Leutz. 1994. Novel mechanism of C/EBPβ (NF-M) transcriptional control: activation through derepression. Genes Dev. 8:2781-2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kowenz-Leutz, E., and A. Leutz. 1999. A C/EBP beta isoform recruits the SWI/SNF complex to activate myeloid genes. Mol. Cell 4:735-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krüger, G., M. Huber, and C. Bonifer. 1999. The −3.9 kb DNase I-hypersensitive site of the chicken lysozyme locus harbors an enhancer with unusual chromatin reorganizing activity. Gene 236:63-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kundu, T. K., V. B. Palhan, Z. Wang, W. An, P. A. Cole, and R. G. Roeder. 2000. Activator-dependent transcription from chromatin in vitro involving targeted histone acetylation by p300. Mol. Cell 6:551-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leahy, P., D. R. Crawford, G. Grossman, R. Gronostajski, and R. W. Hanson. 1999. CREB binding protein coordinates the function of multiple transcription factors including nuclear factor1 to regulate phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 274:8813-8822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lefevre, P., J. Kontaraki, and C. Bonifer. 2001. Identification of factors mediating the developmental regulation of the −3.9 kb chicken lysozyme enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:4551-4560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Litt, M. D., M. Simpson, M. Gaszner, C. D. Allis, and G. Felsenfeld. 2001. Correlation between histone lysine methylation and developmental changes at the chicken beta-globin locus. Science 293:2453-2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Litt, M. D., M. Simpson, F. Recillas-Targa, M. N. Prioleau, and G. Felsenfeld. 2001. Transitions in histone acetylation reveal boundaries of three separately regulated neighboring loci. EMBO J. 20:2224-2235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lutz, M., L. J. Burke, G. Barreto., F. Goeman, H. Greb, R. Arnold, H. Schultheiss, A. Brehm, T. Kouzarides, V. Lobanenkov, and R. Renkawitz. 2000. Transcriptional repression by the insulator protein CTCF involves histone deacetylases. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:1707-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maxam, A. M., and W. Gilbert. 1980. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 65:499-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Metz, T., and T. Graf. 1991. v-myb and v-ets transform chicken erythroid cells and cooperate both in trans and in cis to induce distinct differentiation phenotypes. Genes Dev. 5:369-380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mink, S., B. Haenig, and K. H. Klempnauer. 1997. Interaction and functional collaboration of p300 and C/EBPβ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:6609-6617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miyamoto, T., H. Iwasaki, B. Reizis, M. Ye, T. Graf, D. L. Weissman, and K. Akashi. 2002. Myeloid or lymphoid promiscuity as a critical step in hematopoietic commitment. Dev. Cell 3:137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Müller, K., and N. Mermod. 2000. The histone-interacting domain of nuclear factor I activates simian virus 40 DNA replication in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 275:1645-1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ness, S. A., E. Kowenz-Leutz, T. Casini, T. Graf, and A. Leutz. 1993. Myb and NF-M: combinatorial activators of myeloid genes in heterologous cell types. Genes Dev. 7:749-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pfeifer, G. P., R. Drouin, A. D. Riggs, and G. P. Holmquist. 1992. Binding of transcription factors generates hot spots for UV photoproducts in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12:1798-1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pina, B., U. Brüggemeier, and M. Beato. 1990. Nucleosome positioning modulates accessibility of regulatory proteins to the mouse mamary tumor virus promoter. Cell 60:719-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sippel, A. E., H. Saueressig, M. C. Huber, H. C. Hoefer, A. Stief, U. Borgmeyer, and C. Bonifer. 1996. Identification of cis-acting elements as DNase I-hypersensitive sites in lysozyme chromatin. Methods Enzymol. 274:233-246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soutoglou, E., and I. Talianidis. 2002. Coordination of PIC assembly and chromatin remodeling during differentiation-induced gene activation. Science 295:1901-1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steiner, C., M. Muller, A. Baniahmad, and R. Renkawitz. 1987. Lysozyme gene activity in chicken macrophages is controlled by positive and negative regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:4163-4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tagoh, H., R. Himes, D. Clarke, P. Leenen, A. D. Riggs, D. Hume, and C. Bonifer. 2002. Transcription factor complex formation and chromatin fine structure alterations at the murine c-fms (CSF-1 receptor) locus during myeloid precursor maturation. Genes Dev. 16:1721-1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tenen, D. G., R. Hromas, J. D. Licht, and D. E. Zhang. 1997. Transcription factors, normal myeloid development, and leukemia. Blood 90:489-519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Thomassin, H., E. J. Oakeley, and T. Grange. 1999. Identification of 5-methylcytosine in complex genomes. Methods 19:465-475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thomson, S., A. L. Clayton, and L. C. Mahadevan. 2001. Independent dynamic regulation of histone phosphorylation and acetylation during immediate-early gene induction. Mol. Cell 8:1231-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tolhuis., B., R. J. Palstra, E. Splinter, F. Grosveld, and W. de Laat. 2002. Looping and Interaction between Hypersensitive Sites in the Active beta-globin Locus. Mol. Cell 10:1453-1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Truong, A. H., and Y. Ben-David. 2000. The role of Fli-1 in normal cell function and malignant transformation. Oncogene 19:6482-6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsai, E. Y., J. V. Falvo, A. V. Tsytsykova, A. K. Barczak, A. M. Reimold, L. H. Glimcher, M. J. Fenton, D. C. Gordon, L. F. Dunn, and A. E. Goldfeld. 2000. A lipopolysaccharide-specific enhancer complex involving Ets, Elk-1, Sp1, and CREB binding protein and p300 is recruited to the tumor necrosis factor alpha promoter in vivo. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6084-6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]