Abstract

Although brain tissue from patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and/or AIDS is consistently infected by HIV type 1 (HIV-1), only 20 to 30% of patients exhibit clinical or neuropathological evidence of brain injury. Extensive HIV-1 sequence diversity is present in the brain, which may account in part for the variability in the occurrence of HIV-induced brain disease. Neurological injury caused by HIV-1 is mediated directly by neurotoxic viral proteins or indirectly through excess production of host molecules by infected or activated glial cells. To elucidate the relationship between HIV-1 infection and neuronal death, we examined the neurotoxic effects of supernatants from human 293T cells or macrophages expressing recombinant HIV-1 virions or gp120 proteins containing the V1V3 or C2V3 envelope region from non-clade B, brain-derived HIV-1 sequences. Neurotoxicity was measured separately as apoptosis or total neuronal death, with apoptosis representing 30 to 80% of the total neuron death observed, depending on the individual virus. In addition, neurotoxicity was dependent on expression of HIV-1 gp120 and could be blocked by anti-gp120 antibodies, as well as by antibodies to the human CCR5 and CXCR4 chemokine receptors. Despite extensive sequence diversity in the recombinant envelope region (V1V3 or C2V3), there was limited variation in the neurotoxicity induced by supernatants from transfected 293T cells. Conversely, supernatants from infected macrophages caused a broader range of neurotoxicity levels that depended on each virus and was independent of the replicative ability of the virus. These findings underscore the importance of HIV-1 envelope protein expression in neurotoxic pathways associated with HIV-induced brain disease and highlight the envelope as a target for neuroprotective therapeutic interventions.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infects the brain, causing dementia in 15 to 20% of patients with AIDS (reviewed in reference 69). The cells chiefly infected by HIV-1 in the brain are monocytoid cells, including blood-derived macrophages and resident microglia, but neurons are not productively infected (45, 79). However, a significant loss of neurons occurs in the brains of AIDS patients (22, 37), which is correlated with neurocognitive impairment (23, 51), similar to reports on lentivirus models of neurovirulence (31, 59, 68). Neuronal damage observed in the brains of AIDS patients is likely caused by direct neuronal injury mediated by shed viral proteins such as gp120 and Tat or indirectly through the production of neurotoxic molecules released from HIV-infected or -activated macrophages and microglia (34).

HIV-1 infection of the brain is also characterized by viral molecular diversity (21, 28, 52, 57, 70, 85, 86) but limited viral protein abundance (6, 80). Previous studies have demonstrated that HIV-1 strains derived from AIDS patients with dementia differ from those derived from nondemented patients, principally in the V1 and V3 sequences of the gp120 envelope protein (40, 70, 82). It has also been recognized for some time that viral envelope sequence diversity influences the occurrence of neurological disease in several retroviral diseases (31, 48, 50, 62, 67, 78). Individual HIV-1 isolates were shown to differ in the ability to induce neuronal apoptosis, and indeed, induction of apoptosis was independent of replication capacity (61). In addition to conferring an enhanced ability to infect microglial cells (77), the V3 region of the HIV envelope has also been shown to influence the release of neurotoxic molecules following infection of macrophages (17, 38, 39, 71) and may be directly neurotoxic (63).

While many studies have shown that viral proteins may be directly toxic to neurons (47, 54, 58), the extent of neurotoxicity caused by assembled virus strains with variable infectivities has not been examined. This issue is highly relevant because a large proportion of an HIV-1 quasispecies within an infected individual are replication incompetent (19, 25, 74, 80). Herein, we tested the hypothesis that viral protein expression without replication capability is sufficient for induction of neuronal death. With a panel of replication-competent and -incompetent virus strains, we examined the relationships among viral replication, viral sequence diversity, and ensuing neuronal survival. The neurotoxic effects of recombinant virus strains expressing brain-derived gp120 sequences from different HIV-1 clades with variable cell entry and replication properties were assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell cultures.

293T cells (American Type Culture Collection) and HeLa-CD4/CXCR4/CCR5 cells (66) were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and a 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco BRL). HeLa-CD4/CXCR4 (clone 1022) cells (13) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS and a 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco BRL) plus 1.0 mg of Geneticin (Gibco BRL) per ml. Human osteosarcoma Ghost-CD4/CXCR4/CCR3 cells (10, 56) were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% FCS and a 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Gibco BRL), supplemented with 500 μg of Geneticin (Gibco BRL) per ml, 100 μg of hygromycin per ml, and 1 μg of puromycin per ml. Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were purified from health donors with Histopaque (Sigma), initially stimulated with 5 μg of concanavalin A per ml, and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium with 15% FCS and 100 IU of interleukin-2 (IL-2) per ml. Human primary monocyte-derived macrophage (MDMs) were isolated from PBMCs by plastic adherence and cultured in RPMI medium (12, 13). Human cholinergic neuronal (LAN-2) cells (provided by Jane Rylett, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada) were maintained in minimum essential medium containing 10% FCS, a 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution, and a 1% N2 supplement (Gibco BRL) and differentiated in Leibovitz's L-15 medium (Gibco BRL) with 10% FCS and 50 μg of gentamicin per ml. Primary human fetal neurons (HFNs; provided by Wee Yong, University of Calgary, Calgary Alberta, Canada) were cultured as previously reported (71).

Virus strains.

Molecular clones pNL4-3 (catalog no. 114) and pNL-Luc-E−R− (the NL4-3 provirus backbone with a luciferase reporter gene insertion; catalog no. 3418) were obtained from the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (Rockville, Md.).

Construction of recombinant (chimeric) virus strains.

Paired recombinant virus strains containing the C2V3 and V1V3 envelope sequences from brain-derived envelope sequences of different HIV subtype clades (A = 2, D = 3, and B = 1) (86) were constructed in the genomic backbone of pNL4-3. PCR-amplified C2V3 region fragments from different clades were inserted into molecular clone p9-16, derived from HIV-1 pNL4-3 (12, 14), by use of the StuI and NheI sites. For insertion of V1V3 envelope fragments, plasmid p66-4 was constructed as follows. p10-17 (12) was cut at the unique PshAI site at position 11280 in the 3′-flanking sequence, and a BamHI linker was inserted to inactivate the PshAI site. The resulting plasmid was digested with EcoRI and StuI, and the pol and env sequences in this region were replaced with a synthetic double-stranded oligonucleotide containing restriction sites for EcoRI, SalI, PshAI, ClaI, and StuI, in that order. This plasmid was then digested with EcoRI and PshAI, and a 0.8-kb PCR fragment derived from p10-17 with oligonucleotides 272 (5′-AGCCATAATAAGAATTCTGC-3′) and 1405C (5′-CTTTAGACTTTGGTCCCATAAA-3′) was inserted to regenerate the original HIV-1 sequence in this region with the addition of a new unique PshAI site at base 6557. The accuracy of this sequence was verified by standard DNA sequencing. Plasmid p66-4 was digested with PshAI and NheI and used to insert V1V3 fragments amplified by PCR from patient brain DNA samples. Correct insertion of the fragment was also confirmed by sequencing.

Pseudotyped virus generation and infection assay.

Virus strains or recombinant virus strains were transfected into 293T cells with CaPO4 transfection method as previously reported (86). Viral particles released into the transfected supernatants were quantified by p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; see below). JRFL-env pseudotyped virus strains were generated by cotransfecting 293T cells with plasmids expressing firefly luciferase within an env-inactivated HIV-1 clone (pNL-Luc-E−R−) and expression vector pCMV containing the HIV-1 JRFL env sequence (JRFL-env; provided by Mark Goldsmith, Gladstone Institute, University of California San Francisco). Chemokine receptor utilization was assayed by a previously described luciferase reporter virus infection assay (86). Briefly, chimeric virus strains and pNL-Luc-E−R− plasmids were transfected into 293T cells with CaPO4. Viral supernatants were harvested 2 days posttransfection, cleared of cell debris by low-speed centrifugation, and used to infect different cell lines expressing different chemokine receptors (HeLa-CD4/CXCR4, HeLa-CD4/CXCR4/CXCR5, and human osteosarcoma Ghost-CD4/CXCR4/CCR3). Infection of target cells by pseudotyped virus led to expression of luciferase, which was quantified in cell lysates 2 days following virus addition, with the Luciferase Assay Kit (PharMingen).

Detection of env-encoded protein expression of recombinant virus strains in transfected 293T cells and supernatants.

To determine the virus expression of env-encoded protein in cells, transfected 293T cells (48 h) were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4), fixed in 95% ethanol, and immunostained with a monoclonal antibody (B13) that recognizes an epitope (TQLLLN) located in the C2 region of the HIV-1 env-encoded protein (1), which was present in all of the virus strains used in this study. Several monoclonal antibodies (provided by George Lewis) directed at envelope peptides of HIV-1 were screened for the ability to react with HIV-1 antigens in ethanol-fixed, HIV-infected HeLa-CD4 cells as previously described (12). Monoclonal antibody B13 was found to be one of the best for specific detection of HIV-infected cells by immunocytochemistry. Following incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, the cells were developed with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine as the substrate and visualized under a light microscope. To detect the secreted envelope protein, the supernatants from transfected 293T cells (48 h) were subjected to Western blotting analysis. Briefly, the supernatants in 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 10% glycerol, 5% SDS, 0.004% bromophenol blue, 2.5% 2-mercaptoethanol) were separated by SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis under reducing condition (41), subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed with the B13 antibody. Following incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, antigens were visualized with a BM Chemiluminescence Blotting Substrate (POD) kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

RT assay.

Reverse transcriptase (RT) activity in culture supernatants was measured by using a protocol described previously (30, 73). Briefly, 10 μl of culture supernatants was cleared of cellular debris by high-speed centrifugation and incubated with 40 μl of a reaction cocktail containing [α-32P]TTP for 2 h at 37°C. Samples were blotted on DE81 ion-exchange chromatography paper (Whatman International, Ltd.) and washed three times for 5 min (each time) in 2× SSC (0.3 M NaCl, 0.03 M sodium citrate) and twice for 5 min (each time) in 95% ethanol. RT levels were measured by liquid scintillation counting. All assays were performed in duplicate and repeated a minimum of two times.

HIV-1 p24 antigen ELISA.

The p24 antigens for viral particles and replication in the supernatants from transfected 293T cells and infected MDMs were measured with the HIV-1 p24 Antigen Capture Assay Kit (AIDS Vaccine Program, National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Md.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The results shown are from two independent experiments with cells obtained from at least two donors with duplicated infections for each donor.

In vitro direct and indirect neurotoxicity assays.

Human cholinergic neuron LAN-2 cells were seeded in 96-well plates (5 × 104/well) and differentiated for 3 days. The supernatants (equivalent p24 antigen values for all clones) from transfected 293T cells (direct neurotoxicity assay) and the supernatants from infected MDMs (the transfected 293T cell supernatants of an equivalent value of p24 antigen for all of the clones used to infect MDMs) (indirect neurotoxicity assay) were applied to the differentiated LAN-2 cells or primary HFNs in serum-free AIM-V medium (Gibco BRL). After 24 h of exposure, neuronal cultures were assessed for apoptosis by the terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end-labeling (TUNEL) method and Cell Death Detection ELISAPLUS and for total neuronal death by the trypan blue exclusion method. TUNEL was conducted with the Fluorescein-FragEL DNA Fragmentation Detection Kit (Oncogene Research Products, Boston, Mass.) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The Cell Death ELISA (quantifying histone-complexed DNA fragments [mono- and oligonucleosomes]) was conducted in accordance with the manufacturer's (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Germany) instructions and expressed as enrichment factor relative to the control (= test/control absorbencies). The results represent the mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments with duplicate wells for each experiment. For the trypan blue exclusion assay, cultures were stained with trypan blue dye (Sigma) for 15 min at room temperature and the cells that failed to exclude the dye were counted in triplicate wells (three to six fields per well; 0.1 mm2/field). Total neuronal death was determined by the number of stained cells of the total number of cells counted and expressed as the fold increase over the control (= [test − control]/control). The results represent the mean ± the SEM of four independent experiments with triplicate wells for each experiment. To assess the blocking effects of anti-envelope, anti-chemokine receptor antibodies (anti-R5 and anti-X4), and G-protein-coupled inhibitor pertussis toxin (PTX) on neurotoxicity, the differentiated LAN-2 cells (for direct neurotoxicity assay) and the MDMs (for indirect neurotoxicity assay) were pretreated with 50 μl of AIM-V medium per well alone (as a control) or containing a 1:25 dilution of antiserum to HIV-1SF2 gp120 (National Institutes of Health AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program catalog no. 385) (43), 3 μg of anti-CCR5 (anti-human CCR5 monoclonal antibody, clone 2D7/CCR5, catalog no. 36461A; PharMingen) per ml, or 5 μg of anti-CXCR4 (anti-human CXCR4 monoclonal antibody, clone 44708.11, catalog no. MAB171; R&D Systems Inc.) per ml for 2 h or with 1 μg of PTX (Sigma) per ml for 30 min before virus infections, followed by neurotoxicity assays. The concentrations of the above reagents that were used were based on preliminary trials. Isotype-matched antibodies were used as controls. The results were expressed as percent reduction compared to the control (= [control − test]/control).

Immunocytochemistry.

To determine the expression of chemokine receptors CCR5 (R5) and CXCR4 (R4) in LAN-2 cells, differentiated LAN-2 cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, blocked for 1 h in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 25% normal goat serum (Sigma) and 0.3% Triton X-100, and incubated for 2 h with 2.5 μg of anti-R5 (same as above) or anti-X4 (same as above) per ml. After being washed with 0.1% Tween 20 in PBS and reacted for 1 h with the secondary antibody (Cy3-conjugated AffiniPure goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G [heavy and light chains]; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.), the chamber slides (Nalgene; Nunc) were mounted with Gelvatol and viewed and photographed under a Fluoview confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus). For the STAT-1 nuclear translocation assay, MDMs pretreated with anti-CCR5, anti-CXCR4, or isotype monoclonal antibodies were infected with the virus strains at an equivalent value of p24 antigen from the supernatants of transfected 293T cells for 2 h. The cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and then subjected to the immunocytochemistry analysis procedure described above, with anti-STAT-1 C terminus mouse monoclonal antibody (catalog no. S21120; BD PharMingen). Results were repeated for at least two or three independent experiments with different human macrophage donors.

Host gene expression and real time RT-PCR.

The transfected 293T supernatants with an equal value of the p24 antigen of all of the virus strains tested were used to infect MDMs. After 24 h, the MDMs were washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and lysed in Trizol (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) in accordance with the manufacturer's guidelines. Total RNA was isolated and dissolved in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water, 1 μg of RNA was used for the synthesis of cDNA, and PCRs were performed as described previously. The primers used were as follows: glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), 5′ primer CCA TGG AGA AGG CTG GGG and 3′ primer CAA AGT TGT CAT GGA TGA CC; TNF-α, 5′ primer AAG CCT GTA GCC CAT GTT GTA and 3′ primer GAA GAC CCC TCC CAG ATA GAT G; IL-1β, 5′ primer GCA CCT TCT TTT CCT TCA TC and 3′ primer CAC TTG TTG CTC CAT ATC CTG TCC C; iNOS, 5′ primer CGC CCT TCC GCA GTT CT and 3′ primer TCC AGG AGG ACA TGC AGC AC. Semiquantitative analysis was performed by monitoring in real time the increase in the fluorescence of the SYBR-green dye on a Bio-Rad i-Cycler. To confirm single-band production, melting-curve analysis was performed and, in addition, reaction mixtures were subjected to 40 cycles of amplification and subsequently analyzed by electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining. All data were normalized against the GAPDH mRNA level and expressed as fold increases relative to the controls.

Statistical analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Instat, version 3.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, Calif.). For comparisons of three or more unmatched groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed, followed by a Tukey-Kramer multiple-comparison posttest to determine differences between specific groups. For data derived from two groups, Student's t test was used. The correlation factor (r) and correlation coefficient (r2) were calculated from the Pearson correlation coefficient. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Recombinant virus strains express env-encoded proteins.

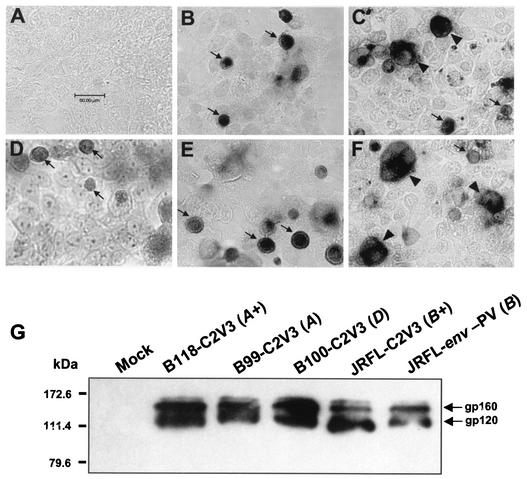

HIV-1 neurovirulence is associated with molecular diversity within several HIV-1 genes (60), and within the env gene, the C2V3 region is important for cell tropism (11, 14-16, 75, 84) and neurotoxicity (61, 71). To elucidate the relationships between viral replication, viral env sequence diversity, and neuronal survival, paired recombinant virus strains containing the C2V3 and/or V1V3 gp120 sequences from brain-derived HIV clades A (n = 2), D (n = 4), and B (n = 1) were constructed in the genomic backbone of pNL4-3 (Table 1) and their infectivity and neurotoxicity were tested and compared to those of the parent pNL4-3 strain and the JRFL-env pseudotyped pNL4-3-Luc-E−R− virus strain (JRFL-env-PV). For detection of env-encoded protein expressed by the recombinant virus strains, 293T cells were transfected with the constructed virus plasmids. With a monoclonal antibody that detects the C2 domain of gp120, all of the recombinant virus strains were found to have gp120 immunopositivity in transfected cells. Representative recombinant virus strains expressed envelope protein, including replication-competent (B118-C2V3; Fig. 1B) and replication-incompetent (B99-C2V3; Fig. 1C) virus strains from clade A, a replication-incompetent virus (B100-C2V3; Fig. 1D) from clade D, a replication-competent virus (JRFL-C2V3; Fig. 1E) from clade B, and the JRFL-env pseudotyped virus (JRFL-env-PV; Fig. 1F). Furthermore, supernatants from cells transfected with each recombinant virus expressed gp120 and gp160 (Fig. 1G) and p24 gag (Table 1). These data indicate that HIV-1 env and gag were expressed by each of the above virus strains and were also released by transfected cells.

TABLE 1.

Features of recombinant and pseudotyped viruses used in this study

| Clone | Sourcea | Clade | gag expressionb | env expressionc | Replication

|

Chemokine receptor used | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBMCs (RT assay) | MDMs (p24 ELISA) | ||||||

| NL-B118-V1V3 | Brain | A | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B118-C2V3 | Brain | A | + | + | + | + | R5 |

| NL-B99-V1V3 | Brain | A | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B99-C2V3 | Brain | A | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B108-V1V3 | Brain | D | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B108-C2V3 | Brain | D | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B102-V1V3 | Brain | D | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B102-C2V3 | Brain | D | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B75-V1V3 | Brain | D | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B75-C2V3 | Brain | D | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B100-V1V3 | Brain | D | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-B100-C2V3 | Brain | D | + | + | − | − | |

| NL-S100-V1V3 | Spleen | D | + | + | + | + | X4 |

| NL-JRFL-V1V3 | Brain | B | + | + | + | + | R5 |

| NL-JRFL-C2V3 | Brain | B | + | + | + | + | R5 |

| pNL4-3 | Blood | B | + | + | + | − | X4 |

| JRFL-env | Brain | B | − | − | |||

| JRFL-env-PV | Brain | B | + | + | − | − | R5 |

| LucR−E− | Blood | B | + | − | − | − | |

From Zhang et al. (86).

gag expression detected in the supernatants of transfected 293T cells, as measured by p24 ELISA.

env expression confirmed by immunocytochemistry and Western blotting.

Coreceptor usages was determined by infection of CD4/CCR5/CXCR4/CCR3-transfected cell lines.

FIG. 1.

Recombinant and pseudotyped virus strains express gp160 and gp120 env-encoded proteins. env-encoded protein expression was detected in transfected 293T cells (A to F) and supernatants (G) by immunocytochemistry and Western blotting analyses, respectively. Representative clones for different clades and replication-competent and -incompetent recombinant virus strains, together with JRFL-env pseudotyped pNL4-3-Luc-E−R− virus (JRFL-env-PV), were tested. Panels: A, mock-transfected 293T cells (negative control); B, B118-C2V3 (clade A); C, B99-C2V3 (clade A); D, B100-C2V3 (clade D); E, JRFL-C2V3 (clade B); F, JRFL-env-PV. Arrows indicate immunopositive cells, while arrowheads highlight syncytium formation and a plus sign indicates a replication-competent virus. Original magnification, ×400; bar, 50 μm for all panels.

Viral replication and cell entry.

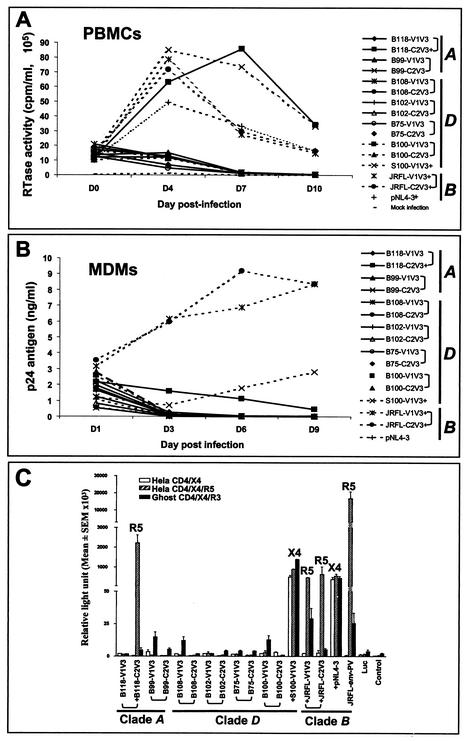

Human PBMCs are infected by most of the strains of HIV-1 tested, including T- and M-tropic virus strains (7, 44, 76, 81). To explore the replication kinetics of the above recombinant virus strains, viral replication was examined in PBMCs and MDMs. Four chimeric virus strains (B118-C2V3, S100-V1V3, JRFL-C2V3, and JRFL-V1V3) replicated in PBMCs (Fig. 2A) and MDMs (Fig. 2B). The remaining recombinant virus strains did not exhibit consistent replication in PBMCs or MDMs despite two or three passages in PBMCs from three different donors (Fig. 2A and B).

FIG. 2.

Replication kinetics and cell entry by recombinant virus strains. A subset of recombinant virus strains showed high RT levels in PBMCs (A); all of the virus strains tested (except pNL4-3) that replicated in PBMCs also exhibited infection of MDMs, as measured by p24 ELISA (B). PBMCs or MDMs were infected with equivalent amounts of p24 antigen of each virus. Replication-competent virus strains entered and expressed luciferase in one or more of the cell lines, depending on their use of chemokine receptors (C). Three brain-derived chimeric virus strains (B118-C2V3, JRFL-C2V3, and JRFL-V1V3) and the JRFL-env pseudotyped virus (JRFL-env-PV) used CCR5 for infections, while the spleen-derived chimeric virus (NL-S100-V1V3) and the parent virus, pNL4-3, used CXCR4 as a coreceptor for virus entry. The replication-incompetent recombinant virus strains did not enter any of these cell lines, on the basis of luciferase activity. The results represent the means and SEM of data from three experiments (triplicate wells in each experiment). The virus clade is indicated, as are paired C2V3 and V1V3 virus strains (brackets). A plus sign denotes a replication-competent virus. The coreceptors used by the virus strains are shown at the top (R5 for CCR5 and X4 for CXCR4). Luc, pNL4-3-LucE−R−; control, cell background control without infection.

Since several recombinant virus strains did not replicate in permissive cell lines, we investigated cell entry and chemokine receptor use in which infectivity was determined with cell lines expressing different chemokine receptors (HeLa-CD4/X4/R5, HeLa-CD4/X4, and human osteosarcoma Ghost-hCD4/X4/R3). Three brain-derived chimeric virus strains (B118-C2V3, JRFL-C2V3, and JRFL-V1V3), as well as JRFL-env pseudotyped virus (JRFL-env-PV), utilized CCR5 for infections, while the spleen-derived chimeric virus (S100-V1V3) and the parent virus (pNL4-3) used CXCR4 as a coreceptor for virus entry (Fig. 2C). The replication-incompetent recombinant virus strains did not enter any of these cell lines (Fig. 2C), suggesting that the absence of productive infection of PBMCs and MDMs by the replication-incompetent virus strains was due to a block in cell entry (Table 1).

Comparison of total and apoptotic neuronal death caused by recombinant virus strains.

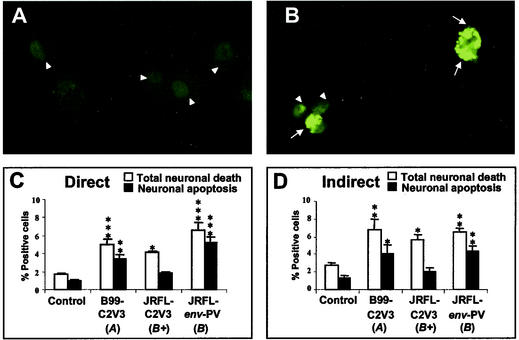

Neuronal injury and death in HIV infection are assumed to occur through mechanisms that are direct, caused by shed viral proteins, or indirect, mediated by neurotoxic host factors released from the infected or activated glial cells (34). To examine the neurotoxicity (neuronal cytotoxicity) of the recombinant virus strains, the supernatants from transfected 293T cells (direct neurotoxicity) and supernatants from HIV-infected macrophages (indirect neurotoxicity) were applied to the human neuronal cell line LAN-2. These studies were conducted with two recombinant virus strains (B99-C2V3 and JRFL-C2V3) and a pseudotyped virus strain (JRFL-env-PV) (Table 1) to determine total neuronal death by trypan blue exclusion and neuronal apoptosis by the TUNEL method (Fig. 3). Each virus strain induced significant direct and indirect total neuronal death, compared to the control (mock-infected cells), while apoptosis represented a major proportion of the total neuronal death for each virus in direct (Fig. 3C) and indirect (Fig. 3D) neurotoxicity assays.

FIG. 3.

Recombinant and pseudotyped virus strains induce neuronal necrosis and apoptosis. Representative images of neuronal (LAN-2) cells treated with supernatants from mock-infected macrophages (A) or macrophages infected with a pseudotyped virus strain (JRFL-env-PV) (B), showing apoptotic (TUNEL-positive) cells with a bright green signal (arrows) and live nonreactive cells exhibiting dull green (arrowheads). Comparisons were made of the mean cell death percentages (±SEM) for total neuronal cell death and neuronal apoptosis cells in direct (C) and indirect (D) neurotoxicity assays. Original magnification, ×200. The statistical significance of differences from the controls was determined by ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). The letters A and B in parentheses indicate virus clades, and a plus sign indicates a replication-competent virus strain.

Direct and indirect neurotoxicity caused by a panel of recombinant virus strains.

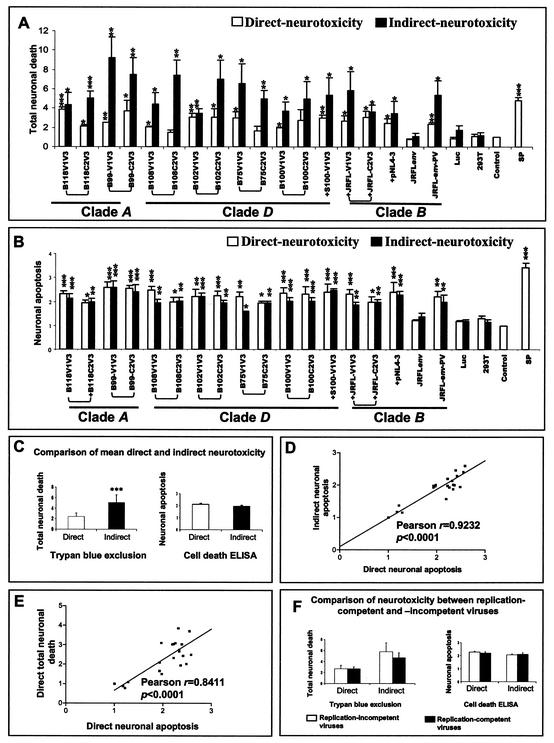

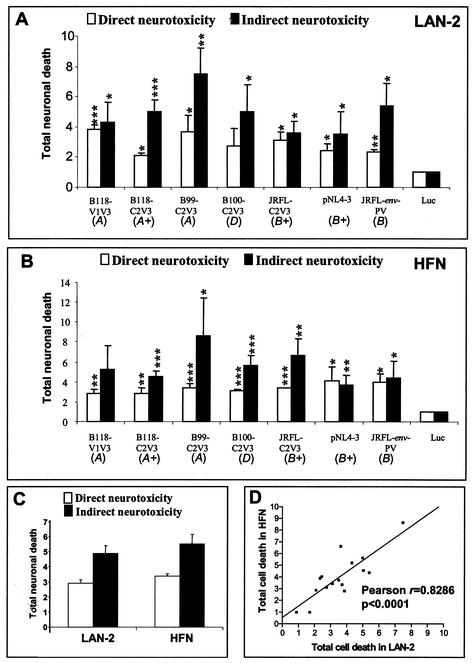

The above analysis was subsequently extended to all recombinant virus strains, revealing that all of the virus strains examined herein caused neurotoxicity (Fig. 4A and B). The extent of neurotoxicity measured as total neuronal death varied for each individual virus, presumably because of sequence variation in the recombinant regions. As measured by total neuronal death, supernatants from infected macrophages (indirect assay) caused consistently higher levels of toxicity than supernatants of transfected 293T cells (direct assay) (P < 0.001). The extent of neuronal apoptosis (Fig. 4B) varied slightly among different virus strains but was closely correlated between the indirect and direct assays for individual virus strains (Fig. 4B, C, and D). For both assays of neuronal death, neurotoxicity was independent of the ability of the virus to replicate (Fig. 4F). Moreover, comparison of the levels of indirect and direct neurotoxicity did not differ among virus strains from different clades although most virus strains exhibited some neurotoxic ability.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of direct and indirect neurotoxicity assays. Supernatants from transfected 293T cells (direct neurotoxicity) or from infected macrophages (indirect neurotoxicity) were applied to the human neuronal cell line LAN-2, followed by examination of the mean fold increase (±SEM) in total neuronal death (A) and the mean enrichment factor (±SEM) in neuronal apoptosis (B). Minimal cell death was observed for the luciferase-expressing vector (Luc), mock-infected 293T-derived supernatants (293T), and medium alone (Control), but staurosporine (SP, 0.2 μM) caused apoptotic cell death. (C) Comparison of mean direct and indirect neurotoxicity for both total neuronal death and apoptotic death for all of the viruses tested. (D) Correlation between direct and indirect neuronal apoptosis for all of the virus strains tested. (E) Correlation of direct neurotoxicity between apoptotic and total neuronal death for all of the virus strains tested. (F) Comparison of neurotoxicity between replication-competent and -incompetent viruses for both apoptotic and total neuronal death. Virus clades are underlined, and paired C2V3 and V1V3 virus strains are indicated by brackets. A plus sign denotes a replication-competent virus strain. The background neuronal death determined by trypan blue exclusion in the medium control varied in individual experiments (ranging from 2.3 to 5.1%). The statistical significance of differences from the medium control was determined by the Student t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01, ***; P < 0.001).

Susceptibilities of different neuronal cell lines to neurotoxicity.

To address differences in susceptibility to neurotoxicity by different neuronal cell types, we compared cell survival in primary HFNs with that in LAN-2 cells in both the direct and indirect neurotoxicity assays measured by trypan blue exclusion for a subset of virus strains (Fig. 5). For both LAN-2 cells (Fig. 5A) and HFNs (Fig. 5B), the levels of neurotoxicity varied among individual virus strains but was independent of replicative properties. In both neuronal cell lines, supernatants of infected macrophages were more toxic than supernatants of transfected 293T cells (Fig. 5C and D). These findings suggest that cultured neuronal LAN-2 cells responded similarly to primary HFNs in the neurotoxicity assays used in this study.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of neurotoxicity in neuronal LAN-2 cells and primary HFNs. Direct and indirect total neuronal death was analyzed for LAN-2 cells (A) and HFNs (B). (C) Comparison of mean direct and indirect neurotoxicity among all of the virus strains tested for each cell type. (D) Correlation of direct and indirect total neuronal death between LAN-2 cells and primary neurons. The background neuronal death determined by trypan blue exclusion in the medium control varied in the individual experiments (ranging from 3.1 to 4.6%). The letters A, B, and D indicate virus clades, and a plus sign indicates a replication-competent virus. The statistical significance of differences from the Luc control was determined by the Student t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Envelope- and chemokine receptor-mediated neurotoxicity.

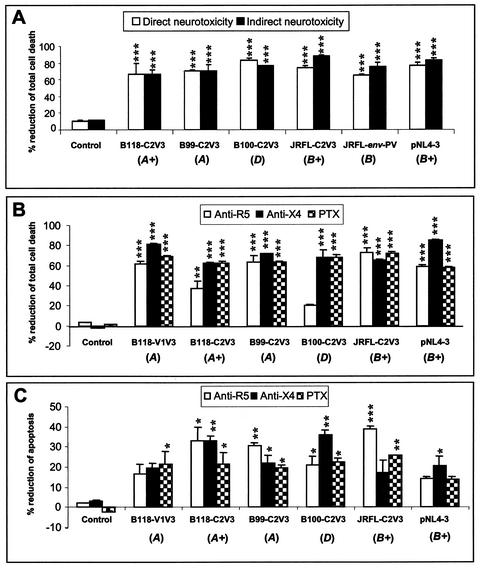

To confirm that the neurotoxicity described above was mediated by the HIV-1 envelope, anti-gp120 polyclonal antibodies that recognized multiple HIV-1 strains were added to supernatants from cells transfected with HIV-1 prior to application to macrophages or neurons. These studies revealed that the anti-gp120 antibodies significantly reduced total cell death in both direct and indirect neurotoxicity assays (Fig. 6A), indicating that the neurotoxicity induced by the recombinant virus strains was mediated largely by the envelope protein.

FIG. 6.

Envelope- and chemokine receptor-mediated neurotoxicity. (A) Anti-envelope antibodies significantly reduced the mean percentage (±SEM) of direct and indirect neurotoxicity caused by recombinant virus strains in total neuronal death. (B) Anti-R5 and anti-X4 monoclonal antibodies and the G-protein-coupled receptor inhibitor PTX also reduced the mean percentage of direct neurotoxicity mediated by recombinant virus strains in both total neuronal-death (B) and apoptosis (C) assays. The statistical significance of differences from the untreated control was determined by ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). The letters A, B, and D in parentheses indicate virus clades, and a plus sign indicates a replication-competent virus.

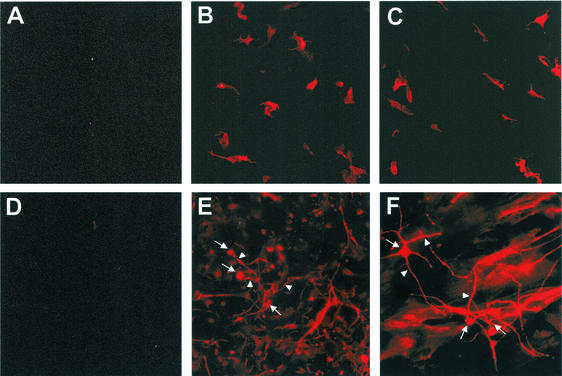

Although neurons express the CXCR4 and CCR5 chemokine receptors, these cells are nonpermissive to HIV-1 entry and replication (26, 34, 72); however, these receptors may still be important for interactions with HIV-1 envelope protein leading to neurotoxicity. Immunocytochemistry analysis with anti-hCCR5 or anti-hCXCR4 monoclonal antibodies confirmed that both LAN-2 cells and primary HFNs expressed both CCR5 and CXCR4 (Fig. 7). Despite the presence of these coreceptors on LAN-2 and primary neurons, viral entry into neurons was not detected by a luciferase assay (data not shown), likely because of the absence of CD4 on these cells (26, 65, 83).

FIG. 7.

Chemokine receptor expression and activation. Human neuronal LAN-2 cells (A to C) and primary HFNs (D to F) expressed both the CCR5 (B and E) and CXCR4 (C and F) chemokine receptors, respectively, on neuronal perikarya (arrows) and neurites (arrowheads). Panels A and D represent immunostaining with isotype-matched antibodies.

To determine if the neurotoxicity induced by these recombinant virus strains was mediated through CCR5, CXCR4, or other chemokine receptors, LAN-2 cells (for the direct neurotoxicity assay) and primary human macrophages (for the indirect neurotoxicity assay) were pretreated with anti-CCR5 or anti-CXCR4 antibodies or the G-protein-coupled receptor inhibitor PTX before virus infection and subsequent neurotoxicity was investigated with assays of total (Fig. 6B) and apoptotic (Fig. 6C) neuronal death for a subset of replicating and nonreplicating virus strains. These studies revealed that the anti-CCR5 and anti-CXCR4 antibodies and PTX reduced direct neurotoxicity, ranging from 20 to 80% in total neuronal-death assays (Fig. 6B) and from 15 to 33% in neuronal apoptosis assays (Fig. 6C), depending on the individual virus strain and the specific inhibitor. In contrast, in assays of indirect neurotoxicity, PTX and the chemokine receptor antibodies did not influence neuronal survival (data not shown). Isotype-matched antibodies did not prevent neuronal death in the above assays (data not shown). These data indicate that chemokine receptors were integral components in HIV-mediated direct neuronal death, but indirect neurotoxicity caused by macrophage supernatants following infection may occur through different mechanisms.

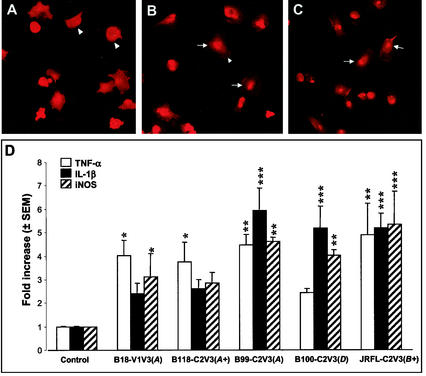

Induction of STAT-1 activation and cytokine production.

The cascade of macrophage-microglia cell signaling events that leads to the production of different neurotoxins and inflammatory molecules is a pivotal mechanism in the execution of HIV-1 indirect neurotoxicity (34, 45, 69). HIV-1 gp120 and the chemokine receptors regulate a variety of cell functions through activation of specific signal transduction pathways, especially the JAK/STAT pathway (30). To examine if the recombinant HIV-1 clones studied as described above can activate the JAK/STAT signal pathway, immunostaining with monoclonal antibodies against STAT-1 was done with primary human macrophages and cultured neuronal LAN-2 cells following infection with these recombinant virus strains. In these experiments, both replication-competent and -incompetent recombinant virus strains induced the nuclear translocation of STAT-1 in macrophages (Fig. 8B and C) but not in LAN-2 cells (data not shown) after exposure to supernatants from transfected cells, suggesting that these virus strains are able to activate this important host cell signaling pathway in macrophages.

FIG. 8.

Induction of STAT-1 nuclear translocation and expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and iNOS. Representative images of human macrophages mock infected (A) or infected with a replication-competent (B118-C2V3) (B) or a replication-incompetent (B100-C2V3) (C) recombinant virus strain, showing STAT-1 immunoreactivity in cytoplasm (arrowheads) and in nuclei following translocation (arrows) 2 h after exposure of cells to neurotoxic supernatants. (D) Real time RT-PCR was performed with primary human macrophage cultures, and the results are expressed relative to the GAPDH mRNA level, revealing that all of the virus strains tested induced mean fold increases in TNF-α, IL-1β, and iNOS mRNA levels that were independent of viral replicative properties. The statistical significance of differences from the uninfected control was determined by ANOVA (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). The letters A, B, and D in parentheses indicated virus clades, and a plus sign indicates a replication-competent virus. Original magnification, ×400.

To investigate if the above-described recombinant HIV-1 clones can induce the expression of cytokines and other potential neurotoxins in macrophages, real-time RT-PCR was performed with RNA from primary human macrophages following exposure to different virus strains. Both replication-competent and -incompetent virus strains induced 2.4- to 5.9-fold increases in tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA levels in primary macrophages infected with different virus strains, compared with uninfected control cells (Fig. 8D). These observations support the hypothesis that viral protein expression alone is sufficient for HIV-induced release of neurotoxins from macrophages.

DISCUSSION

Viral replication and cell tropism are key aspects of HIV-related systemic disease progression, with high viral loads being indicative of immune failure together with the emergence of X4-dependent virus strains and CD4 T-lymphocyte depletion (9, 18, 42, 46). In contrast, the development of HIV-associated dementia is not closely coupled with the viral load in the brain despite a correlation between dementia severity and the cerebrospinal fluid viral load (8, 20, 53). The explanation for this dichotomy remains unclear, but in retrovirus models of neuropathogenesis, the viral load is also not always correlated with neurovirulence (32, 59, 67, 68). The present findings corroborate these in vivo observations by showing that the gp120 viral envelope protein is essential for neurotoxicity despite the lack of replicative capability of some virus strains. Moreover, it suggests that the mere presence of the viral envelope protein at the cell membrane is sufficient for induction of neurotoxic mechanisms. In support of this concept, earlier data from a mouse retroviral model showed induction of local brain pathology by defective viral vectors capable only of expressing viral envelope protein (49). This assumption is supported by the extensive literature indicating that the HIV-1 gp120 envelope protein, usually derived from an X4-dependent virus, is neurotoxic (4, 5, 35, 54, 55, 58). In addition, many of the virus strains isolated from the blood and brain are replication defective but may express viral proteins, as in the present studies, thereby emphasizing the above observations of neurotoxicity caused by such virus strains in vitro.

In the present study of both immortalized and primary human neurons, we found that all of the virus strains tested induced cell death directly and indirectly. Although the extent of neurotoxicity varied between individual virus strains, it was not clear which envelope sequence motifs were responsible for the neurotoxicity. Comparison of recombinant clones with the V1V3 or C2V3 region derived from the same patient did not indicate a consistent relationship between the level of neurotoxicity and the presence or absence of the V1V2 region. There were also no distinct differences in the neurotoxicity induced by clones from different clades, in contrast to previous data suggesting an influence of clade type on progression of systemic disease (33).

The mechanisms by which neurons die during HIV infection remain controversial, with both apoptosis and necrosis participating in neuronal death (2, 35). Apoptosis accounts for a subset of dying neurons, but it is not correlated with the presence or absence of dementia (2, 3, 24). Phagocytosis of necrotic cells by monocytoid cells induces innate immune activation with the release of TNF-α and IL-1β, while phagocytosis of apoptotic cells fails to prime monocytoid cells but instead results in transforming growth factor β release (29). In the present studies, apoptotic cell death represented a greater fraction of the total cell death than did necrosis, on the basis of the relative fold increase in cell death and depending on the individual virus. However, it remains unclear if either of these neurotoxic pathways is responsible for clinical HIV-1-induced brain disease, as neither is easily correlated with clinical dementia. Similarly, in a model of mouse retroviral brain disease, morphological changes such as glial activation and neuronal death are detectable after infection with avirulent virus clones (67). Infection with neurovirulent clones leads to neurobehavioral abnormalities, which are correlated with upregulation of certain cytokines (TNF-α) and chemokines (IP-10, MCP-1, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES) (64). These events precede the neurobehavioral signs and thus may be important causes of the pathogenic process. A similar process may occur in patients with HIV and/or AIDS, but it has not been possible to obtain data regarding the expression levels of these cytokines and chemokines within the brain before and during the evolution of the HIV-associated dementia syndrome.

Our observations that antibodies to the HIV-1 envelope inhibited with direct and indirect neurotoxicity underline the importance of the envelope gp120 protein for induction of neurotoxicity. Two surprising findings in the present study include the inhibition of direct neuronal death by antibodies to both CCR5 and CXCR4 chemokine receptors, regardless of the coreceptor preference of the individual clones, and the failure of the same antibodies to block indirect neuronal death mediated by macrophage-derived supernatants. The first finding may be explained by antibody blocking of binding of chemokine receptors by virions or free gp120 in 293T supernatants. The second observation implies that engagement of CCR5 or CXCR4 by non-virion-associated gp120 present in macrophage supernatants is not sufficient to induce neurotoxicity. This is compatible with our finding that neurotoxicity is independent of viral replication but suggests that other neurotoxic mechanisms are activated. One possible mechanism may involve the receptor for advanced glycation end products, which is known to exert effects on the JAK/STAT pathway (27). To date, an interaction between the glycosylation of the HIV-1 envelope and the receptor for advanced glycation end products has not been reported.

Although the panel of virus strains used in this study was tested in several different assays of neuronal death, we did not confirm the present observations in vivo. In part, this is because there are few models that recapitulate in vivo HIV-1 infection of the brain. The recent development of a human CD4/CCR5 transgenic rat model (36) will provide an opportunity to test the hypothesis that replication-defective virus strains mediate neurovirulence, which is dependent on viral genetic diversity. Nevertheless, with the increased interest in developing attenuated virus strains or vectors expressing several HIV genes as vaccines, attention will need to be paid to their potential neurotropism and neurovirulence, given that viral gene expression in the brain is sufficient from the development of neuronal injury. The utility of such a transgenic model is obvious, given the above issues, and is currently under investigation.

Acknowledgments

These studies were supported by CIHR, CANFAR, and the Neuroscience Canada Foundation. K.Z. is an Henri M. Toupin Medical Foundation Fellow, and C.P. is an AHFMR Scholar/CIHR Investigator.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abacioglu, Y. H., T. R. Fouts, J. D. Laman, E. Claassen, S. H. Pincus, J. P. Moore, C. A. Roby, R. Kamin-Lewis, and G. K. Lewis. 1994. Epitope mapping and topology of baculovirus-expressed HIV-1 gp160 determined with a panel of murine monoclonal antibodies. AIDS Res. Hum. Retrovir. 10:371-381. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Adle-Biassette, H., F. Chretien, L. Wingertsmann, C. Hery, T. Ereau, F. Scaravilli, M. Tardieu, and F. Gray. 1999. Neuronal apoptosis does not correlate with dementia in HIV infection but is related to microglial activation and axonal damage. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 25:123-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adle-Biassette, H., Y. Levy, M. Colombel, F. Poron, S. Natchev, C. Keohane, and F. Gray. 1995. Neuronal apoptosis in HIV infection in adults. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 21:218-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bagetta, G., M. T. Corasaniti, L. Berliocchi, M. Navarra, A. Finazzi-Agro, and G. Nistico. 1995. HIV-1 gp120 produces DNA fragmentation in the cerebral cortex of rat. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 211:130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagetta, G., M. T. Corasaniti, W. Malorni, G. Rainaldi, L. Berliocchi, A. Finazzi-Agro, and G. Nistico. 1996. The HIV-1 gp120 causes ultrastructural changes typical of apoptosis in the rat cerebral cortex. Neuroreport 7:1722-1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bell, J. E., A. Busuttil, J. W. Ironside, S. Rebus, Y. K. Donaldson, P. Simmonds, and J. F. Peutherer. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus and the brain: investigation of virus load and neuropathologic changes in pre-AIDS subjects. J. Infect. Dis. 168:818-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolton, V., N. C. Pedersen, J. Higgins, M. Jennings, and J. Carlson. 1987. Unique p24 epitope marker to identify multiple human immunodeficiency virus variants in blood from the same individuals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 25:1411-1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brew, B. J., L. Pemberton, P. Cunningham, and M. G. Law. 1997. Levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in cerebrospinal fluid correlate with AIDS dementia stage. J. Infect. Dis. 175:963-966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao, Y., L. Qin, L. Zhang, J. Safrit, and D. D. Ho. 1995. Virologic and immunologic characterization of long-term survivors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:201-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cecilia, D., V. N. KewalRamani, J. O'Leary, B. Volsky, P. Nyambi, S. Burda, S. Xu, D. R. Littman, and S. Zolla-Pazner. 1998. Neutralization profiles of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates in the context of coreceptor usage. J. Virol. 72:6988-6996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan, S. Y., R. F. Speck, C. Power, S. L. Gaffen, B. Chesebro, and M. A. Goldsmith. 1999. V3 recombinants indicate a central role for CCR5 as a coreceptor in tissue infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 73:2350-2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chesebro, B., J. Nishio, S. Perryman, A. Cann, W. O'Brien, I. S. Chen, and K. Wehrly. 1991. Identification of human immunodeficiency virus envelope gene sequences influencing viral entry into CD4-positive HeLa cells, T-leukemia cells, and macrophages. J. Virol. 65:5782-5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, J. Metcalf, and D. E. Griffin. 1991. Use of a new CD4-positive HeLa cell clone for direct quantitation of infectious human immunodeficiency virus from blood cells of AIDS patients. J. Infect. Dis. 163:64-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, J. Nishio, and S. Perryman. 1992. Macrophage-tropic human immunodeficiency virus isolates from different patients exhibit unusual V3 envelope sequence homogeneity in comparison with T-cell-tropic isolates: definition of critical amino acids involved in cell tropism. J. Virol. 66:6547-6554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chesebro, B., K. Wehrly, J. Nishio, and S. Perryman. 1996. Mapping of independent V3 envelope determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 macrophage tropism and syncytium formation in lymphocytes. J. Virol. 70:9055-9059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cocchi, F., A. L. DeVico, A. Garzino-Demo, A. Cara, R. C. Gallo, and P. Lusso. 1996. The V3 domain of the HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein is critical for chemokine-mediated blockade of infection. Nat. Med. 2:1244-1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham, A. L., H. Naif, N. Saksena, G. Lynch, J. Chang, S. Li, R. Jozwiak, M. Alali, B. Wang, W. Fear, A. Sloane, L. Pemberton, and B. Brew. 1997. HIV infection of macrophages and pathogenesis of AIDS dementia complex: interaction of the host cell and viral genotype. J. Leukoc. Biol. 62:117-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doms, R. W., and S. C. Peiper. 1997. Unwelcomed guests with master keys: how HIV uses chemokine receptors for cellular entry. Virology 235:179-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donaldson, Y. K., J. E. Bell, J. W. Ironside, R. P. Brettle, J. R. Robertson, A. Busuttil, and P. Simmonds. 1994. Redistribution of HIV outside the lymphoid system with onset of AIDS. Lancet 343:383-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellis, R. J., K. Hsia, S. A. Spector, J. A. Nelson, R. K. Heaton, M. R. Wallace, I. Abramson, J. H. Atkinson, I. Grant, and J. A. McCutchan. 1997. Cerebrospinal fluid human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA levels are elevated in neurocognitively impaired individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 42:679-688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein, L. G., C. Kuiken, B. M. Blumberg, S. Hartman, L. R. Sharer, M. Clement, and J. Goudsmit. 1991. HIV-1 V3 domain variation in brain and spleen of children with AIDS: tissue-specific evolution within host-determined quasispecies. Virology 180:583-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everall, I. P., P. J. Luthert, and P. L. Lantos. 1991. Neuronal loss in the frontal cortex in HIV infection. Lancet 337:1119-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox, L., M. Alford, C. Achim, M. Mallory, and E. Masliah. 1997. Neurodegeneration of somatostatin-immunoreactive neurons in HIV encephalitis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 56:360-368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gelbard, H. A., H. J. James, L. R. Sharer, S. W. Perry, Y. Saito, A. M. Kazee, B. M. Blumberg, and L. G. Epstein. 1995. Apoptotic neurons in brains from paediatric patients with HIV-1 encephalitis and progressive encephalopathy. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 21:208-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gosztonyi, G., J. Artigas, L. Lamperth, and H. D. Webster. 1994. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) distribution in HIV encephalitis: study of 19 cases with combined use of in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 53:521-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hesselgesser, J., and R. Horuk. 1999. Chemokine and chemokine receptor expression in the central nervous system. J. Neurovirol. 5:13-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang, J. S., J. Y. Guh, H. C. Chen, W. C. Hung, Y. H. Lai, and L. Y. Chuang. 2001. Role of receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE) and the JAK/STAT-signaling pathway in AGE-induced collagen production in NRK-49F cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 81:102-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hughes, E. S., J. E. Bell, and P. Simmonds. 1997. Investigation of the dynamics of the spread of human immunodeficiency virus to brain and other tissues by evolutionary analysis of sequences from the p17gag and env genes. J. Virol. 71:1272-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huynh, M. L., V. A. Fadok, and P. M. Henson. 2002. Phosphatidylserine-dependent ingestion of apoptotic cells promotes TGF-β1 secretion and the resolution of inflammation. J. Clin. Investig. 109:41-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnston, J. B., Y. Jiang, G. van Marle, M. B. Mayne, W. Ni, J. Holden, J. C. McArthur, and C. Power. 2000. Lentivirus infection in the brain induces matrix metalloproteinase expression: role of envelope diversity. J. Virol. 74:7211-7220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnston, J. B., and C. Power. 2002. Feline immunodeficiency virus xenoinfection: the role of chemokine receptors and envelope diversity. J. Virol. 76:3626-3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnston, J. B., C. Silva, and C. Power. 2002. Envelope gene-mediated neurovirulence in feline immunodeficiency virus infection: induction of matrix metalloproteinases and neuronal injury. J. Virol. 76:2622-2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanki, P. J., D. J. Hamel, J. L. Sankale, C. Hsieh, I. Thior, F. Barin, S. A. Woodcock, A. Gueye-Ndiaye, E. Zhang, M. Montano, T. Siby, R. Marlink, I. NDoye, M. E. Essex, and S. MBoup. 1999. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtypes differ in disease progression. J. Infect. Dis. 179:68-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaul, M., G. A. Garden, and S. A. Lipton. 2001. Pathways to neuronal injury and apoptosis in HIV-associated dementia. Nature 410:988-994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaul, M., and S. A. Lipton. 1999. Chemokines and activated macrophages in HIV gp120-induced neuronal apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8212-8216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Keppler, O. T., F. J. Welte, T. A. Ngo, P. S. Chin, K. S. Patton, C. L. Tsou, N. W. Abbey, M. E. Sharkey, R. M. Grant, Y. You, J. D. Scarborough, W. Ellmeier, D. R. Littman, M. Stevenson, I. F. Charo, B. G. Herndier, R. F. Speck, and M. A. Goldsmith. 2002. Progress toward a human CD4/CCR5 transgenic rat model for de novo infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Exp. Med. 195:719-736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ketzler, S., S. Weis, H. Haug, and H. Budka. 1990. Loss of neurons in the frontal cortex in AIDS brains. Acta Neuropathol. 80:92-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khanna, K. V., X. F. Yu, D. H. Ford, L. Ratner, J. K. Hildreth, and R. B. Markham. 2000. Differences among HIV-1 variants in their ability to elicit secretion of TNF-α. J. Immunol. 164:1408-1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong, L. Y., B. C. Wilson, M. K. McMillian, G. Bing, P. M. Hudson, and J. S. Hong. 1996. The effects of the HIV-1 envelope protein gp120 on the production of nitric oxide and proinflammatory cytokines in mixed glial cell cultures. Cell Immunol. 172:77-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuiken, C. L., J. Goudsmit, G. F. Weiller, J. S. Armstrong, S. Hartman, P. Portegies, J. Dekker, and M. Cornelissen. 1995. Differences in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V3 sequences from patients with and without AIDS dementia complex. J. Gen. Virol. 76:175-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy, J. A. 1993. HIV pathogenesis and long-term survival. AIDS 7:1401-1410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levy, J. A., A. D. Hoffman, S. M. Kramer, J. A. Landis, J. M. Shimabukuro, and L. S. Oshiro. 1984. Isolation of lymphocytopathic retroviruses from San Francisco patients with AIDS. Science 225:840-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levy, J. A., B. Ramachandran, E. Barker, J. Guthrie, and T. Elbeik. 1996. Plasma viral load, CD4+ cell counts, and HIV-1 production by cells. Science 271:670-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lipton, S. A., and H. E. Gendelman. 1995. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. Dementia associated with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:934-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Littman, D. R. 1998. Chemokine receptors: keys to AIDS pathogenesis? Cell 93:677-680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu, Y., M. Jones, C. M. Hingtgen, G. Bu, N. Laribee, R. E. Tanzi, R. D. Moir, A. Nath, and J. J. He. 2000. Uptake of HIV-1 tat protein mediated by low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein disrupts the neuronal metabolic balance of the receptor ligands. Nat. Med. 6:1380-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lynch, W. P., S. Czub, F. J. McAtee, S. F. Hayes, and J. L. Portis. 1991. Murine retrovirus-induced spongiform encephalopathy: productive infection of microglia and cerebellar neurons in accelerated CNS disease. Neuron 7:365-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lynch, W. P., and J. L. Portis. 2000. Neural stem cells as tools for understanding retroviral neuropathogenesis. Virology 271:227-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mankowski, J. L., M. T. Flaherty, J. P. Spelman, D. A. Hauer, P. J. Didier, A. M. Amedee, M. Murphey-Corb, L. M. Kirstein, A. Munoz, J. E. Clements, and M. C. Zink. 1997. Pathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus encephalitis: viral determinants of neurovirulence. J. Virol. 71:6055-6060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Masliah, E., N. Ge, C. L. Achim, L. A. Hansen, and C. A. Wiley. 1992. Selective neuronal vulnerability in HIV encephalitis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 51:585-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mayne, M., A. C. Bratanich, P. Chen, F. Rana, A. Nath, and C. Power. 1998. HIV-1 tat molecular diversity and induction of TNF-α: implications for HIV-induced neurological disease. Neuroimmunomodulation 5:184-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McArthur, J. C., D. R. McClernon, M. F. Cronin, T. E. Nance-Sproson, A. J. Saah, M. St Clair, and E. R. Lanier. 1997. Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus-associated dementia and viral load in cerebrospinal fluid and brain. Ann. Neurol. 42:689-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meucci, O., A. Fatatis, A. A. Simen, T. J. Bushell, P. W. Gray, and R. J. Miller. 1998. Chemokines regulate hippocampal neuronal signaling and gp120 neurotoxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:14500-14505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meucci, O., and R. J. Miller. 1996. gp120-induced neurotoxicity in hippocampal pyramidal neuron cultures: protective action of TGF-β1. J. Neurosci. 16:4080-4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Michael, N. L., J. A. E. Nelson, V. N. KewalRamani, G. Chang, S. J. O'Brien, J. R. Mascola, B. Volsky, M. Louder, G. C. White II, D. R. Littman, R. Swanstrom, and T. R. O'Brien. 1998. Exclusive and persistent use of the entry coreceptor CXCR4 by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from a subject homozygous for CCR5 Δ32. J. Virol. 72:6040-6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morris, A., M. Marsden, K. Halcrow, E. S. Hughes, R. P. Brettle, J. E. Bell, and P. Simmonds. 1999. Mosaic structure of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genome infecting lymphoid cells and the brain: evidence for frequent in vivo recombination events in the evolution of regional populations. J. Virol. 73:8720-8731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Muller, W. E., H. C. Schroder, H. Ushijima, J. Dapper, and J. Bormann. 1992. gp120 of HIV-1 induces apoptosis in rat cortical cell cultures: prevention by memantine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 226:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murray, E. A., D. M. Rausch, J. Lendvay, L. R. Sharer, and L. E. Eiden. 1992. Cognitive and motor impairments associated with SIV infection in rhesus monkeys. Science 255:1246-1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nath, A., and J. Geiger. 1998. Neurobiological aspects of human immunodeficiency virus infection: neurotoxic mechanisms. Prog. Neurobiol. 54:19-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ohagen, A., S. Ghosh, J. He, K. Huang, Y. Chen, M. Yuan, R. Osathanondh, S. Gartner, B. Shi, G. Shaw, and D. Gabuzda. 1999. Apoptosis induced by infection of primary brain cultures with diverse human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: evidence for a role of the envelope. J. Virol. 73:897-906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paquette, Y., Z. Hanna, P. Savard, R. Brousseau, Y. Robitaille, and P. Jolicoeur. 1989. Retrovirus-induced murine motor neuron disease: mapping the determinant of spongiform degeneration within the envelope gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:3896-3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pattarini, R., A. Pittaluga, and M. Raiteri. 1998. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 envelope protein gp120 binds through its V3 sequence to the glycine site of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors mediating noradrenaline release in the hippocampus. Neuroscience 87:147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterson, K. E., S. J. Robertson, J. L. Portis, and B. Chesebro. 2001. Differences in cytokine and chemokine responses during neurological disease induced by polytropic murine retroviruses map to separate regions of the viral envelope gene. J. Virol. 75:2848-2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peudenier, S., C. Hery, K. H. Ng, and M. Tardieu. 1991. HIV receptors within the brain: a study of CD4 and MHC-II on human neurons, astrocytes and microglial cells. Res. Virol. 142:145-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Platt, E. J., K. Wehrly, S. E. Kuhmann, B. Chesebro, and D. Kabat. 1998. Effects of CCR5 and CD4 cell surface concentrations on infections by macrophagetropic isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J. Virol. 72:2855-2864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Poulsen, D. J., S. J. Robertson, C. A. Favara, J. L. Portis, and B. W. Chesebro. 1998. Mapping of a neurovirulence determinant within the envelope protein of a polytropic murine retrovirus: induction of central nervous system disease by low levels of virus. Virology 248:199-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Power, C., R. Buist, J. B. Johnston, M. R. Del Bigio, W. Ni, M. R. Dawood, and J. Peeling. 1998. Neurovirulence in feline immunodeficiency virus-infected neonatal cats is viral strain specific and dependent on systemic immune suppression. J. Virol. 72:9109-9115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Power, C., and R. T. Johnson. 2001. Neuroimmune and neurovirological aspects of human immunodeficiency virus infection. Adv. Virus Res. 56:389-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Power, C., J. C. McArthur, R. T. Johnson, D. E. Griffin, J. D. Glass, S. Perryman, and B. Chesebro. 1994. Demented and nondemented patients with AIDS differ in brain-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope sequences. J. Virol. 68:4643-4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Power, C., J. C. McArthur, A. Nath, K. Wehrly, M. Mayne, J. Nishio, T. Langelier, R. T. Johnson, and B. Chesebro. 1998. Neuronal death induced by brain-derived human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope genes differs between demented and nondemented AIDS patients. J. Virol. 72:9045-9053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rottman, J. B., K. P. Ganley, K. Williams, L. Wu, C. R. Mackay, and D. J. Ringler. 1997. Cellular localization of the chemokine receptor CCR5. Correlation to cellular targets of HIV-1 infection. Am. J. Pathol. 151:1341-1351. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sears, J. F., R. Repaske, and A. S. Khan. 1999. Improved Mg2+-based reverse transcriptase assay for detection of primate retroviruses. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:1704-1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sinclair, E., F. Gray, A. Ciardi, and F. Scaravilli. 1994. Immunohistochemical changes and PCR detection of HIV provirus DNA in brains of asymptomatic HIV-positive patients. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 53:43-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Speck, R. F., K. Wehrly, E. J. Platt, R. E. Atchison, I. F. Charo, D. Kabat, B. Chesebro, and M. A. Goldsmith. 1997. Selective employment of chemokine receptors as human immunodeficiency virus type 1 coreceptors determined by individual amino acids within the envelope V3 loop. J. Virol. 71:7136-7139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spira, A. I., and D. D. Ho. 1995. Effect of different donor cells on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication and selection in vitro. J. Virol. 69:422-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Strizki, J. M., A. V. Albright, H. Sheng, M. O'Connor, L. Perrin, and F. Gonzalez-Scarano. 1996. Infection of primary human microglia and monocyte-derived macrophages with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates: evidence of differential tropism. J. Virol. 70:7654-7662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Szurek, P. F., P. H. Yuen, J. K. Ball, and P. K. Y. Wong. 1990. A Val-25-to-Ile substitution in the envelope precursor polyprotein, gPr80env, is responsible for the temperature sensitivity, inefficient processing of gPr80env, and neurovirulence of ts1, a mutant of Moloney murine leukemia virus TB. J. Virol. 64:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takahashi, K., S. L. Wesselingh, D. E. Griffin, J. C. McArthur, R. T. Johnson, and J. D. Glass. 1996. Localization of HIV-1 in human brain using polymerase chain reaction/in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. Ann. Neurol. 39:705-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Teo, I., C. Veryard, H. Barnes, S. F. An, M. Jones, P. L. Lantos, P. Luthert, and S. Shaunak. 1997. Circular forms of unintegrated human immunodeficiency virus type 1 DNA and high levels of viral protein expression: association with dementia and multinucleated giant cells in the brains of patients with AIDS. J. Virol. 71:2928-2933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsai, W. P., S. R. Conley, H. F. Kung, R. R. Garrity, and P. L. Nara. 1996. Preliminary in vitro growth cycle and transmission studies of HIV-1 in an autologous primary cell assay of blood-derived macrophages and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Virology 226:205-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van Marle, G., S. B. Rourke, K. Zhang, C. Silva, J. Ethier, M. J. Gill, and C. Power. 2002. HIV dementia patients exhibit reduced viral neutralization and increased envelope sequence diversity in blood and brain. AIDS 16:1905-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Volsky, D. J. 1990. Fusion of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) with human cells as measured by membrane fluorescence dequenching (DQ) method: roles of HIV-1-cell fusion in AIDS pathogenesis. Prog. Clin. Biol. Res. 343:179-198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Westervelt, P., D. B. Trowbridge, L. G. Epstein, B. M. Blumberg, Y. Li, B. H. Hahn, G. M. Shaw, R. W. Price, and L. Ratner. 1992. Macrophage tropism determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in vivo. J. Virol. 66:2577-2582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wong, J. K., C. C. Ignacio, F. Torriani, D. Havlir, N. J. S. Fitch, and D. D. Richman. 1997. In vivo compartmentalization of human immunodeficiency virus: evidence from the examination of pol sequences from autopsy tissues. J. Virol. 71:2059-2071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhang, K., M. Hawken, F. Rana, F. J. Welte, S. Gartner, M. A. Goldsmith, and C. Power. 2001. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 clade A and D neurotropism: molecular evolution, recombination, and coreceptor use. Virology 283:19-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]