Abstract

Most rhesus macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239 with nef deleted (either Δnef or ΔnefΔvprΔUS [Δ3]) control viral replication and do not progress to AIDS. Some monkeys, however, develop moderate viral load set points and progress to AIDS. When simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) recovered from two such animals (one Δnef and the other Δ3) were serially passaged in rhesus monkeys, the SIVs derived from both lineages were found to consistently induce moderate viral loads and disease progression. Analysis of viral sequences in the serially passaged derivatives revealed interesting changes in three regions: (i) an unusually high number of predicted amino acid changes (12 to 14) in the cytoplasmic domain of gp41, most of which were in regions that are usually conserved; these changes were observed in both lineages; (ii) an extreme shortening of nef sequences in the region of overlap with U3; these changes were observed in both lineages; and (iii) duplication of the NF-κB binding site in one lineage only. Neither the polymorphic gp41 changes alone nor the U3 deletion alone appeared to be responsible for increased replicative capacity because recombinant SIVmac239Δnef, engineered to contain either of these changes, induced moderate viral loads in only one of six monkeys. However, five of six monkeys infected with recombinant SIVmac239Δnef containing both TM and U3 changes did develop persisting moderate viral loads. These genetic changes did not increase lymphoid cell-activating properties in the monkey interleukin-2-dependent T-cell line 221, but the gp41 changes did increase the fusogenic activity of the SIV envelope two- to threefold. These results delineate sequence changes in SIV that can compensate for the loss of the nef gene to partially restore replicative and pathogenic potential in rhesus monkeys.

Simian immunodeficiency virus SIVmac239, derived from cloned DNA of defined sequence, consistently induces post-acute-phase viral loads, or set points, in the range of 105 to 107 RNA molecules per ml of plasma and consistently induces progression to AIDS in a time frame suitable for laboratory investigation (38). Knockout of the nef gene in this clone by deletion of 182 bp results in a replication-competent attenuated derivative; viral loads at peak height around week 2 are approximately 1.5 logs lower than those of the parental virus, and viral loads at set point are less than 300 copies per ml of plasma in the majority of animals (36, 39). Others have observed similar phenotypic effects from the deletion of nef with a distinct independent clone (18). Monkeys infected with SIVmac239 with nef deleted are often but not always strongly protected against challenge with wild-type pathogenic SIV (6, 17-19, 36, 71, 72). Monkeys infected with SIVmac239Δ3 (missing nef, vpr, and U3 sequences that overlap nef) typically manifest viral loads at set point that are below the limit of detection (21).

A variety of functional activities have been reported for the nef gene product. Both HIV-1 Nef and SIVmac Nef downregulate a number of cellular proteins from the surface of cells. These include CD4 and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I molecules (1, 10, 29, 52, 64). Downregulation of MHC class I molecules can make nef-expressing cells less susceptible to recognition by cytotoxic T lymphocytes (14, 16). Both HIV-1 Nef and SIVmac Nef can increase the state of lymphoid cell activation by causing increased signaling inside cells (3, 23, 24, 49, 62, 66, 67, 70). Both tyrosine kinase and serine-threonine kinase cascades have been implicated in this activity (15, 31, 55, 58, 60). Additional activities and a wide variety of cellular partners have been reported for HIV-1 Nef (2, 9, 32, 47, 55, 63, 68). While it is likely that nef does indeed make a number of different, distinct functional contributions to the viral life cycle in vivo, their relative importance remains uncertain.

Not all animals infected with SIV deleted of nef control the infection. In studies at the New England Regional Primate Research Center with more than 25 monkeys, 15 to 20% of juveniles and adults infected with SIVmac239 strains with nef deleted or with nef, vpr, and US deleted (Δ3) developed moderate viral loads and eventually progressed with disease (K. Mansfield et al., manuscript in preparation). The number may be higher under different conditions or in other hands (6, 17). Certainly, neonatal rhesus monkeys infected with these strains at birth are more susceptible to disease progression than juveniles and adults (7, 8, 73). Both host factors and sequence changes in the virus following in vivo replication could contribute to the propensity to cause disease. The studies described in this report were directed at determining whether compensatory changes in the virus imparted increased replicative capacity on SIVmac239 deleted of nef in rhesus monkeys and what the nature of such compensatory changes might be.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid construction.

gp41 transmembrane (TM) sequences isolated from animal Mm138-95 (ITM) were inserted into the NheI and SacI restriction sites of pSP72SIV3′Δnef to create p3′ITMΔnef. To create p5′ΔnefΔUS138KK, which contained an extreme shortening of nef sequences in the U3 region (ΔUS) and a duplication of the NF-κB binding site (138KK) (57), SIV sequences isolated from Mm138-95 were inserted into the SacI and KasI restriction sites of p239SpSp5′. To create p3′ΔnefΔUS138KK, these sequences were inserted into the SacI and EcoRI restriction sites of pSP72SIV3′. For the construction of 5′ and 3′ SIVΔnefΔUS, the 5′-proximal NF-κB site was deleted from both p5′ΔnefΔUS138KK and p3′ΔnefΔUS138KK with an overlap extension technique (33). ITM sequences were inserted into p3′ΔnefΔUS138 and p3′ΔnefΔUS138KK with NheI and SacI restriction sites to create p3′ITMΔnefΔUS138 and p3′ITMΔnefΔUS138KK, respectively.

For the construction of p3′ITMΔnef/GFP, green fluorescent protein (GFP) sequences from pSIVΔnefEGFP (4) were inserted into the SacI and EcoRI sites of p3′ITMΔnef. Mutagenic primers were then used to introduce a HindIII site immediately 5′ of the start codon of SIV tat-1 and env sequences and a ClaI site immediately 3′ of the GFP sequences of p3′ITMΔnef/GFP. Insertion of this fragment into the HindIII and ClaI sites of pSIVSEAP (53) eliminated the secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) gene and generated pLTR/ITM/GFP. Analogous manipulations were employed on SIV239Δnef sequences to create pLTR/CTM/GFP, which contained wild-type SIV gp41 transmembrane sequences (CTM).

Generation of recombinant SIV stocks.

Recombinant SIV stocks were generated by DEAE-dextran transfection of the cell line CEMx174 (54). For these experiments, 5′ and 3′ SIV sequences were digested with the restriction enzyme SphI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), and the resulting fragments were joined with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) prior to transfection. Transfected CEMx174 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL). Virus was harvested at or near the peak of virus production as previously described (30). The levels of p27Gag viral protein produced from transfections or contained in viral isolates were quantified with an SIV core antigen kit (Coulter, Hialeah, Fla.).

Experimental infection of rhesus macaques.

Recombinant SIV diluted to contain 50 ng of p27Gag antigen was inoculated intravenously into juvenile rhesus monkeys. At various times postinoculation, blood samples were collected from these animals as previously described (30). Animals that became moribund were sacrificed, and complete necropsies were performed.

Determination of viral RNA and infectious cell loads.

Virion-associated SIV RNA in plasma samples was quantified as previously described by reverse transcription-PCR assay on an Applied Biosystems Prism 7700 sequence detection system (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) (46, 69). Cell-associated viral loads were determined by quantitative cocultivation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with CEMx174 cells (21). PBMC were purified, counted on a hemacytometer, and cocultured with CEMx174 cells in various numbers. On day 21, the presence of SIV p27Gag antigen was determined, and the number of PBMC needed to recover SIV was calculated. The results presented here represent averages of duplicate determinations.

PCR amplification of recombinant SIV sequences recovered from PBMC.

Cellular DNA was isolated with a saturated NaCl precipitation protocol (5). SIV-specific primers that were designed to have annealing temperatures of approximately 70°C, as determined by the oligo primer analysis program (National Biosciences, Plymouth, Minn.), were used. The PCR mixture, which included rTthXL (Perkin-Elmer Cetus), was heated to 80°C for 60 s prior to the addition of 1.0 mM magnesium acetate. The samples were inserted into an Omnigene PCR cycler (Hybaid, Franklin, Mass.) that had been preheated to 80°C. Seventy-five cycles of PCR were used to amplify the SIV sequences. Each cycle consisted of a 93°C denaturation step followed by a rapid-cooling step to 70°C, and then a slow-cooling step, followed by a 65°C polymerization step. PCR resulted in single homogenous fragments (data not shown), and therefore, a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) was employed for purification prior to sequence analyses. The entire SIV sequence was determined with SIV-specific primers with an ABI 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). Full-length 5′ and 3′ SIV sequences were amplified so that they could be joined at an SphI restriction site to produce full-length SIV DNA for transfection in CEMx174 cells for the creation of virus stocks.

Sequences of individual clones were aligned with the parental SIVmac239 to identify unusual sequence changes in the monkey-passaged virus. Regions containing such unusual changes were reamplified from monkey-passaged stocks, sequences representing the predominant species were established, and an individual representative clone was used for the construction of recombinant viruses.

221 cell infections.

One million unstimulated 221 cells (no exogenous interleukin-2) suspended in 1 ml of RPMI supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum were incubated in a 48-well tissue culture plate (Corning Costar, Cambridge, Mass.). Recombinant SIV diluted to contain 10 ng of p27Gag antigen was used to infect the cells.

Fusogenicity assay.

pLTR/ITM/GFP and pLTR/CTM/GFP DNAs were transfected into 293T cells with the FuGene 6 transfection reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.). The cells were incubated for 3 days in a six-well tissue culture plate (Corning Costar) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco-BRL) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were harvested, and the level of GFP was determined with a Microbeta plate reader (Wallac Oy, Turku, Finland), which was used to standardize transfection efficiency. C8166-45 LTR-SEAP cells, in which secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) expression was driven by SIV long terminal repeat (LTR) sequences (53), were then added to independent wells of pLTR/ITM/GFP or pLTR/CTM/GFP transfected 293T cells. At various times, supernatants were harvested and quantified for SEAP expression with the Phospha-Light chemiluminescent reporter gene assay system (Tropix, Bedford, Mass.) and a Microbeta plate reader.

RESULTS

Replication and virulence of monkey-passed SIVΔnef.

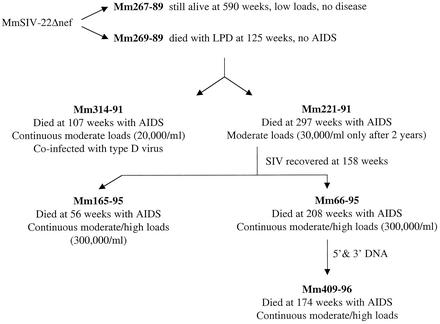

Two juvenile rhesus macaques (Mm267-89 and Mm269-89) were experimentally infected with SIVΔnef. The env sequences in the Δnef variant that was used were derived from a naturally occurring sequence variant of SIVmac239 described by Burns and Desrosiers (11). The variant envelope sequences were inserted into SIVmac239Δnef for these experimental infections. Mm267-89 maintained low viral loads and remained healthy for 590 weeks postinoculation, at which time the experiment was terminated (Fig. 1). Mm269-89 died 125 weeks postinoculation with lymphoproliferative disease without symptoms associated with AIDS (Fig. 1). Minced lymph node and spleen from Mm269-89 at the time of death was used to transmit SIV to two additional monkeys (Mm314-91 and Mm221-91). Mm314-91 maintained continuous moderate viral loads and died with AIDS 107 weeks postinoculation (Fig. 1). (The term moderate viral loads is used in this report to refer to those in the range of 103 to 105 RNA copies per ml of plasma.)

FIG. 1.

Lineage of rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with SIVΔnef. The arrows indicate the history of the SIV passage. The viral loads represent SIV RNA copies/ml of plasma. 5′ and 3′ SIV DNA refers to the PCR-generated fragments that were used to generate a viral stock as described in Materials and Methods. LPD, lymphoproliferative disease.

Conversely, in the initial 2 years postinoculation, viral loads were below levels of detection in Mm221-91. However, beginning 2 years postinoculation, moderate viral loads were detected in this animal and were subsequently maintained (Fig. 1). Neither of these animals showed evidence of lymphoproliferative disease. Mm221-91 was sacrificed due to severe diarrhea and wasting at 5.75 years after the experimental infection. Although CD4 counts in Mm221-91 around the time of sacrifice represented 41 to 43% of total PBMC (542 cells/μl), necropsy findings revealed pulmonary Pneumocystis carinii, intestinal adenovirus, and lymphoid changes characteristic of AIDS. SIV recovered from Mm221-91 at 158 weeks postinoculation was used to experimentally infect two additional monkeys (Mm165-95 and Mm66-95). These animals maintained continuous moderate to high viral loads and died 56 and 208 weeks postinoculation, respectively (Fig. 1). The 5′ and 3′ SIV sequences were amplified by PCR from DNA of cells infected with virus isolated from Mm66-95. These fragments were used to create a viral stock which was used to infect Mm409-96. Mm409-96 maintained continuous moderate viral loads and died 174 weeks postinoculation (Fig. 1).

Replication and virulence of monkey-passed SIVΔ3.

One monkey of six that were infected in parallel with SIVΔ3 behaved atypically and maintained continuous moderate loads and progressed to death with AIDS by 260 weeks postinoculation. SIV isolated from this monkey (Mm301-91) at week 209 postinoculation was used to infect two additional monkeys (Mm138-95 and Mm132-95) that subsequently maintained moderate to high and moderate viral loads, respectively (Fig. 2). Mm138-95 died accidentally from complications unrelated to AIDS at 162 weeks postinoculation. The 5′ and 3′ SIV sequences were amplified from Mm138-95 by PCR. The 3′ fragment was joined to the 5′ fragment derived either from Mm138-95 or from PCR-amplified wild-type SIVmac239 5′ sequences. These DNAs were transfected into CEMx174 cells, and the resulting stocks were used to infect two monkeys (Mm339-96 and Mm392-96). Mm339-96 maintained continuous low viral loads (Fig. 2). In contrast, Mm392-96, which was infected with a stock that contained wild-type 5′ and monkey-passaged 3′ sequences, maintained high viral loads and died with AIDS at 35 weeks postinoculation (Fig. 2). This observation suggested that sequences in the 3′ monkey-passaged SIVΔ3 sequences may be important for increased replication and virulence.

FIG. 2.

Lineage of rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with SIVΔ3. The arrows indicate the history of the SIV passage. The viral loads represent SIV RNA copies/ml of plasma. 5′ and 3′ SIV DNAs generated by PCR were used to generate viral stocks as described in Materials and Methods. RRV, rhesus monkey rhadinovirus.

Necropsy findings.

Animals inoculated with serially passaged SIVmac239Δnef died with lesions characteristic of virulent SIVmac infection. Survival, CD4 count at death, and presence of AIDS-defining pathology are summarized in Table 1. Animals Mm314-91 and Mm221-91 were euthanized for chronic diarrhea and wasting. In animal Mm314-91, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex involving the small intestine, liver, lungs, and multiple lymph nodes was diagnosed. Animal Mm221-91 developed multiple opportunistic infections, including adenovirus infection of the small intestine and pulmonary P. carinii. Animals Mm165-95 and Mm66-95 were inoculated with virus isolated from animal Mm221-91 and euthanized at 383 and 1,432 days, respectively. At death, both had depletion in the absolute number of CD4 T cells in peripheral blood and simian AIDS-defining pathology identified at necropsy. Animal Mm165-95 had multiple opportunistic infections, including cryptosporidia and cytomegalovirus infection, and animal Mm66-95 had SIV arteriopathy and an enteropathy characterized by villous atrophy and glandular epithelial cell hyperplasia. Finally, animal Mm409-96 received virus isolated from Mm66-95 and died with multiple opportunistic infections 1,199 days following infection. At necropsy, multiple pulmonary pathogens, including P. carinii, Streptococcus sp., and adenovirus, were found along with enteric cryptosporidiosis.

TABLE 1.

Survival, CD4 count at death, and simian AIDS-defining pathology following inoculation with serially passaged SIVmac239 deleted of nef

| Serially passaged virus | Animal no. | Viral inoculum | Survival (days) | Cause of death | % CD4 cells at death (absolute no. ul)a | Simian AIDS-defining pathology | Opportunistic infections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIV22Δnef | Mm314-91 | SIV isolated from Mm269-89 | 739 | Opportunistic infection | 3 (17) | Opportunistic infections and giant cell disease | Mycobacterium avium |

| Mm221-91 | SIV isolated from Mm269-89 | 2,050 | Multiple opportunistic infections | 43 (542) | Opportunistic infections and giant cell disease | Pneumocystis carinii, adenovirus | |

| Mm165-95 | SIV isolated from Mm221-91 | 383 | Multiple opportunistic infections | 43 (516) | Opportunistic infections | Cryptosporidia, cytomegalovirus | |

| Mm66-95 | SIV isolated from Mm221-91 | 1,432 | SIV arteriopathy and endocarditis | 18 (360) | SIV arteriopathy and enteropathy | None | |

| Mm409-96 | SIV isolated from Mm66-95 | 1,199 | Multiple opportunistic infections | NA | Opportunistic infections | Pneumocystis carinii, Streptococcus pneumoniae, adenovirus, cryptosporidia | |

| SIV239Δ3 | Mm138-95 | SIV isolated from Mm301-91 | 1,117 | Euthanized for self-injurious behavior | 29 (872) | SIV arteriopathy | None |

| Mm132-95 | SIV isolated from Mm301-91 | 177 | Accidental death | NA | None | None | |

| Mm339-96 | SIV isolated from Mm138-95 | 1,271 | Euthanized; experiment ended | 55 (1,091) | None | None | |

| Mm392-96 | SIV isolated from Mm38-95 | 242 | Multiple opportunistic infections | 30 (1,014) | Opportunistic infections | Pneumocystis carinii, enterocytozoon, cryptosporidia, adenovirus |

NA, not applicable.

Two of four animals infected with serially passaged SIVmac239Δ3 developed simian AIDS-defining pathology within the time frames of observation. One of these animals was euthanized for self-injurious behavior, and a characteristic SIV arteriopathy was observed morphologically. In the other case, multiple opportunistic infections were diagnosed, including pulmonary Pneumocystis infection and enterocytozoon, cryptosporidium, and adenovirus infection of the gastrointestinal tract. Despite sparing of the absolute and relative number of CD4 T lymphocytes in peripheral blood, these findings are diagnostic of the immunodeficiency syndrome seen in simian AIDS.

Sequences of serially passaged SIVs.

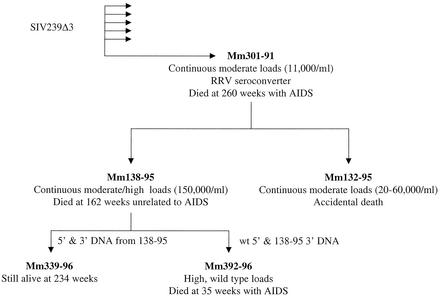

Since passage of SIV derived from both lineages (Δnef and Δ3) consistently induced moderate viral loads and disease progression, we investigated whether these strains had acquired changes that might determine this phenotype. Based on the observation that 3′ sequences in monkey-passaged virus may be important for efficient replication and virulence in Mm392-96, we confined our search for such determinants to sequences in the 3′ half of the genome. For these experiments, the 3′ sequences were ascertained from viruses isolated from two monkeys (one from each lineage) in which continuous moderate to high loads were observed (Mm66-95 and Mm138-95, Fig. 1 and 2). These analyses revealed interesting changes in three regions: the cytoplasmic domain of gp41, nef sequences in the region of overlap with U3, and the NF-κB binding site (Fig. 3) (57).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of SIVmac239, cloned SIVmac recombinant, and monkey-passaged SIVmac sequences. The stars denote nucleotides or amino acids that were homologous with those of SIVmac239, and the dashes denote nucleotides or amino acids that were not contained in a particular sequence. (A) Amino acid alignment of gp41 cytoplasmic tail sequences of SIVmac239 and monkey-passaged sequences isolated from an animal from the Δnef lineage (Mm66-95) and an animal from the Δ3 lineage (Mm138-95). Mm8-22 represents the env sequence used in the lineage leading to Mm66-95. The number 721 denotes the amino acid position in Env in the SIVmac239 strain (57). Areas in grey denote sequences that were invariant in the Los Alamos database that were altered in Mm66-95 and Mm138-95. (B) Nucleotide alignment of nef sequences in the region of overlap with U3 (US). (C) Nucleotide alignment of LTR sequences in the region in which a duplication polymorphism was observed in SIV isolated from Mm138-95. NF-κB binding sites are shown in bold letters.

An unusually large number of sequence changes (12 to 14) were observed in the cytoplasmic domain of gp41 sequences isolated from both Mm66-95 and Mm138-95 (Fig. 3A). Most of these changes were in regions that are usually conserved among SIV isolates (43). In addition, an extreme shortening of nef sequences in the region of overlap with U3 was observed in SIV sequences derived from both monkeys (Fig. 3B). Deletion of sequences in the nef-U3 overlap region over time has been observed previously both in SIVΔnef-infected monkeys (41) and in an HIV-1Δnef-infected human (40). However, in the present cases, the extent of deletion of nef-U3 sequences was extreme (Fig. 3B). A duplication of the NF-κB binding site was also observed in the SIV isolated from Mm138-95 but not that from Mm66-95 (Fig. 3C). We will refer to these sequence changes as ITM (improved transmembrane), ΔUS (deleted in nef-U3 overlap region), and KK (duplication of NF-κB binding site), respectively. Strains with US-deleted sequences reconstructed from monkey Mm138-95 are referred to as ΔUS138.

We compared the sequences in the cytoplasmic domain of TM from Mm66-95 and Mm138-95 to the 13 SIVmac and SIVsm sequences in the Los Alamos database (43). An SSPP sequence (Env amino acids 726 to 729) was invariant in the 13 database sequences but was changed in both of our serial passage lineages, to SPRP in Mm66-95 and to SPPP in Mm138-95. The QIEY sequence (Env amino acids 765 to 768) was invariant in the 13 database sequences but was changed in both of our serial passage lineages, to PIAY in Mm138-95 and to QIAY in Mm66-95. LIRL (Env amino acids 776 to 779) is part of a long stretch of invariant sequences that was changed in Mm138-95. In all, of 26 individual variations in cytoplasmic domain sequences from Mm66-95 and Mm138-95, 11 occurred at sites that were invariant in the database sequences and 5 were polymorphisms that were different from anything in the database.

Experimental infection of rhesus monkeys with recombinant SIVΔnef.

In order to investigate the contribution of these sequence changes to increased viral replication and virulence in rhesus monkeys, four recombinant SIV239Δnef strains were engineered to contain different combinations of sequences derived from Mm138-95 as described in Materials and Methods. Strain SIV-ITMΔnef contained the original nef deletion and ITM sequences from animal Mm138-95. Strain SIVΔnefΔUS138 contained the original nef deletion and the nef-U3 deletion seen in animal Mm138-95. Strain SIV-ITMΔnefΔUS138 contained the original nef deletion and the ITM and the nef-U3 deletion seen in animal Mm138-95. Strain SIV-ITMΔnefΔUS138KK is like SIV-ITMΔnefΔUS138 but with an additional NF-κB binding site. These recombinants were used to experimentally infect juvenile rhesus macaques, which were then monitored for viral loads and disease progression.

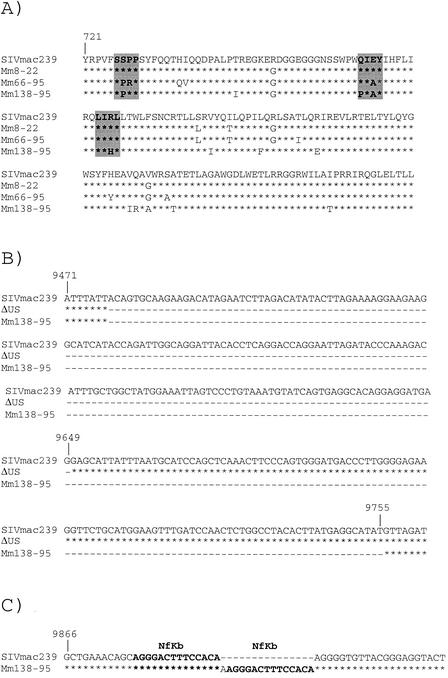

As a control for these experiments, three monkeys were experimentally infected with SIVΔnef. In two of the animals (Mm350-99 and Mm352-99), set point viral RNA and infectious cell loads were continuously below detectable levels (Fig. 4). In the third animal (Mm351-99), low but detectable SIV RNA loads were observed through 64 weeks postinoculation but subsequently dipped to below detectable levels (Fig. 4A). Detectable cell-associated viral loads were also maintained in this animal up to 32 weeks postinoculation, but subsequently decreased to undetectable levels (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Quantification of SIV loads in rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with SIVΔnef. (A) Plasma SIV RNA levels at the indicated weeks postinoculation. The dashed line indicates the threshold sensitivity of the assay (100 copies/ml). (B) Frequency of infectious cells in PBMC. Viral loads were graded on a scale of 0 to 10, indicating the number of PBMC needed to recover SIV: 0, no virus recovered from 106 cells; 1, successful virus recovery from 106 cells; 2 to 10, successful virus recovery from 333,333, 111,111, 37,037, 12,345, 4,115, 1,371, 457, 152, and 51 cells, respectively.

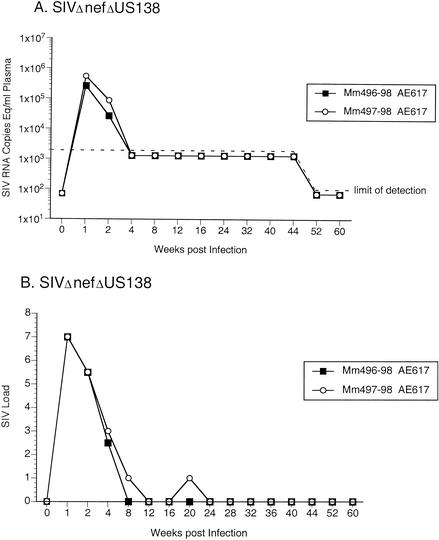

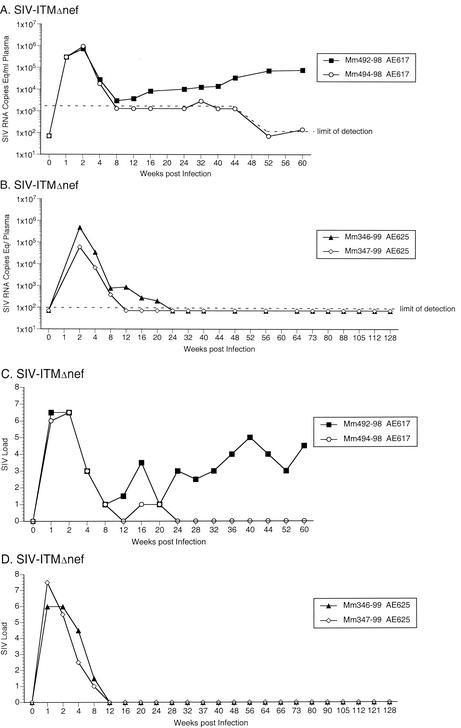

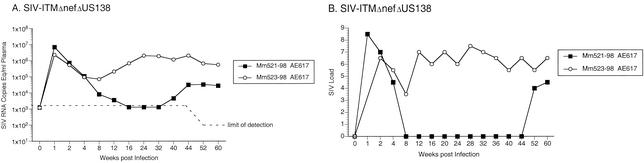

To test for the importance of the extreme shortening of nef sequences in the region of overlap with U3, two monkeys were experimentally infected with SIVΔnefΔUS138. In both of these animals, undetectable viral RNA and cell-associated viral loads were observed beyond week 8 (Fig. 5). To test the effect of ITM sequences on SIV replication efficiency, four monkeys were experimentally infected with SIV-ITMΔnef. One of these animals (Mm492-98) maintained moderate viral RNA and cell-associated SIV load set points, whereas the other three monkeys (Mm494-98, Mm346-99, and Mm347-99) maintained undetectable viral RNA and cell-associated SIV load set points (Fig. 6). The data from the SIVΔnefΔUS138 and SIV-ITMΔnef infection experiments suggested that neither the polymorphic gp41 changes alone nor the U3 deletion alone was responsible for the consistently increased SIVΔnef replicative capacity in vivo.

FIG. 5.

Quantification of SIV loads in rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with SIVΔnefΔUS138. (A) Plasma SIV RNA levels at the indicated weeks postinoculation. The dashed line indicates the threshold sensitivity of the assay (1,500 copies/ml). (B) PBMC-associated viral load. Viral loads were graded on a scale of 0 to 10, indicating the number of PBMC needed to recover SIV as described in the legend to Fig. 4.

FIG. 6.

Quantification of SIV loads in rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with SIV/ITMΔnefΔUS138KK. (A) Plasma SIV RNA levels at the indicated weeks postinoculation from this animal experiment. The dashed line indicates the threshold sensitivity of the assay (1,500 copies/ml). (B) Same as in A for a separate animal experiment. The dashed line indicates the threshold sensitivity of the assay (100 copies/ml). (C) PBMC-associated viral loads. (D) PBMC-associated viral loads.

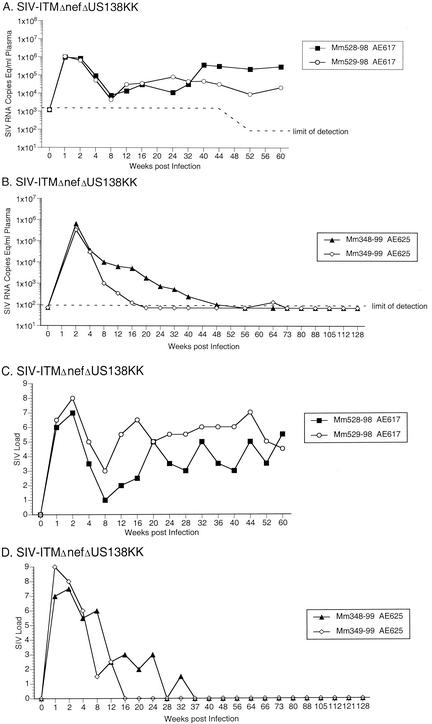

Next, we tested whether the ITM and ΔUS sequence changes in combination could greatly increase viral replication. For the initial experiment, two monkeys were infected with SIV-ITMΔnefΔUS138. Both of these animals (Mm521-98 and Mm523-98) maintained moderate or high viral RNA and cell-associated SIV loads beyond week 40 postinoculation (Fig. 7). To further assess the importance of the ITM and ΔNU sequences in increasing replication capacity, four monkeys were infected with the recombinant SIV/ITMΔnefΔUS138KK. Three of these animals (Mm528-98, Mm529-98, and 348-99) maintained moderate viral RNA load set points for prolonged periods, and two (Mm528-98 and Mm529-98) maintained moderate cell-associated viral load set points (Fig. 8). Thus, four of six monkeys infected with recombinant SIVs containing both the ITM and ΔUS138 polymorphisms developed persistent moderate viral loads and a fifth maintained detectable viral loads for 40 weeks. These data indicate that, together, these polymorphisms were sufficient to increase SIV replication, leading to the maintenance of moderate viral loads in vivo.

FIG. 7.

Quantification of SIV loads of rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with SIV/ITMΔnefΔUS138. (A) Plasma SIV RNA levels at the indicated weeks postinoculation. The dashed line indicates the threshold sensitivity of the assay (1,500 copies/ml). (B) PBMC-associated viral loads. Viral loads were graded on a scale of 0 to 10, indicating the number of PBMC needed to recover SIV.

FIG. 8.

Quantification of SIV loads of rhesus monkeys experimentally infected with SIV/ITMΔnefΔUS138KK. (A) Plasma SIV RNA levels at the indicated weeks postinoculation. (B) Same as in A but for a separate animal experiment. (C) PBMC-associated viral loads. (D) PBMC-associated viral loads.

We next compared viral loads in the six monkeys infected with SIV deleted of nef and containing TM and LTR modifications to viral loads in monkeys infected with the parental SIV239Δnef. Data from monkeys infected with SIV239Δnef were derived from previous as well as the current studies. We had plasma RNA load data from seven monkeys infected with SIV239Δnef and cell load data from 11 monkeys infected with SIV239Δnef to use for these analyses. While there was no significant difference in plasma RNA loads in the acute phase when the six monkeys in Fig. 7 and 8 were compared to the seven monkeys infected with the parental SIV239Δnef, significant differences were observed in the set point values. For example, the mean plasma RNA load at week 24 for the six monkeys shown in Fig. 7 and 8 (3.6 × 105 RNA copies per ml) was significantly higher (P = 0.022 by Mann-Whitney rank sum test) than the mean plasma RNA load at week 24 for the seven monkeys infected with SIV239Δnef (2.7 × 102 RNA copies per ml). Similar statistically significant differences were observed when cell load data were compared at 22 to 28 weeks (P = 0.021) and at 40 to 52 weeks (P = 0.018).

Recombinant SIV replication in 221 cells.

Previously, we demonstrated that nef increased the level of activation of cells in the interleukin-2-dependent monkey T-cell line 221, which resulted in greatly increased levels of SIV replication in the absence of exogenously added interleukin-2 (3). We tested the possibility that monkey-passaged SIVΔnef or SIVΔ3 had acquired the lymphocyte-activating property of nef in this assay. For these experiments, wild-type and Δnef SIVmac239 strains or recombinant strains containing SIV sequences derived from Mm138-95 were used to infect 221 cells in the absence of interleukin-2. As expected, SIVmac239 replicated to much higher levels than did SIVΔnef in this assay (Fig. 9). The recombinant strains replicated like SIVΔnef (Fig. 9), indicating that the monkey-passaged sequences had not conferred lymphocyte-activating activity on these strains in this assay.

FIG. 9.

Replicative capacity of SIV recombinants in unstimulated 221 cells. The cells were incubated without interleukin-2 and infected with virus diluted to contain 10 ng of p27Gag antigen. p27Gag antigen production from infected cultures was quantified at the times indicated.

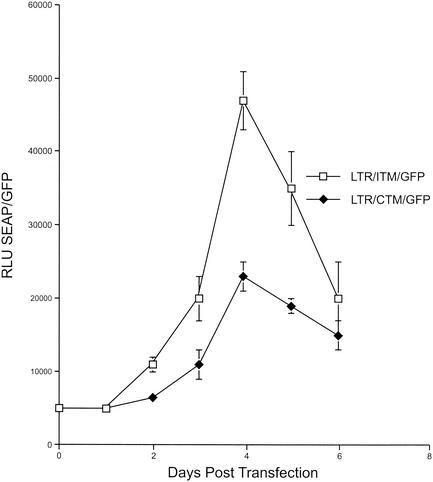

Fusogenic activity of recombinant SIV.

Fusion of the primate lentiviral and host membranes during viral entry is facilitated by gp41 (20, 26). There is considerable evidence that sequences in the cytoplasmic tail of gp41 contribute to this function (12, 13, 25, 28, 42, 45, 48, 50, 65). Based on this information, we examined whether ITM sequences increased the fusogenic activity of SIV. For these experiments, clones in which SIV sequences containing env, tat, and rev as well as GFP sequences were inserted immediately downstream of the SIV LTR were engineered as described in Materials and Methods. Vectors that contained either the gp41 cytoplasmic tail sequences of SIVmac239 (pLTR/CTM/GFP) or the analogous sequences obtained from Mm138-95 (pLTR/ITM/GFP) were engineered. These DNAs were transfected into 293T cells, and GFP expression was assessed to standardize for transfection efficiency. Cultures that were transfected with similar efficiencies were incubated with C8166-45 LTR-SEAP cells, in which secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) expression was driven by SIV LTR sequences (53). Since SEAP expression in these cells was Tat dependent, the level of SEAP expression in these cultures was used as an assay for fusion between the Tat-expressing 293T cells and the SEAP-expressimg C8166-45 LTR-SEAP cells. In these experiments, the amount of SEAP activity, when standardized for GFP expression, was consistently two- to threefold higher for pLTR/ITM/GFP-transfected cells than for pLTR/CTM/GFP-transfected cells (Fig. 10). These data indicated that the ITM sequences had acquired increased fusogenic activity in comparison to CTM sequences.

FIG. 10.

Fusogenic activity of SIVmac239 and monkey-passaged gp41 transmembrane (TM) sequences. 293T cells were transfected with pLTR/CTM/GFP (containing SIVmac239 TM sequences) and pLTR/ITM/GFP (containing monkey-passaged TM sequences) and incubated with C8166-45 LTR-SEAP cells. At the times indicated, cells were analyzed for GFP expression and supernatants were harvested for measurement of secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) activity. The data are expressed as relative light units (RLU) of SEAP or GFP. The data represent two independent quantifications, each from two separate transfection experiments.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate increased replicative capacity of SIV deleted of nef that had been serially passaged in rhesus monkeys. Increased replicative capacity of any SIV strain upon serial monkey passage is not surprising. A pathogenic phenotype associated with an SIV strain completely lacking one of its nine genes is perhaps more surprising. However, pathogenic potential has been noted previously in SIV strains missing vpr or vpx (30), so there is precedent. Similar to the serially passaged Δnef strains, the cloned recombinant Δnef strains with the ITM and ΔUS changes also appeared to have considerably increased replicative capacity compared to what we have seen previously with SIVmac239Δnef (19, 36, 39) (Fig. 4) and compared to what others have seen for SIV deleted of nef (18, 56). Our experiments have necessarily been limited by the number of rhesus monkeys that could be used for the experiments. Consequently, the contributions of NF-κB binding site duplication and changes in the 5′ half of the genome to increased replicative capacity remain uncertain at this time.

The phenotypes of the serially passaged Δnef strains and the compensated clones do not appear to be equivalent to that of wild-type SIVmac239. Viral loads with the parental cloned SIV239 typically average 4 × 107 RNA equivalents per ml of plasma at peak around week 2 postinfection and 3 × 106 RNA equivalents per ml of plasma at set point 20 to 50 weeks postinfection (37). Most of the progressing monkeys infected with compensated SIV deleted of nef appeared to be considerably below these averages, approximately 10- to 100-fold lower both at peak height and at set point. Accepting the limitations of the limited number of monkeys employed, viral loads at peak height and at set point in the six monkeys that were infected with cloned, recombinant SIVΔnef containing the compensatory changes did not appear different from those of the analogous monkeys that were infected with the uncloned, serially passaged strains deleted of nef. This suggests that we have identified the major sequence changes responsible for the compensation.

Inoculation of animals with serially passaged SIVmac239 viruses deleted of nef obtained from animals with progressive disease often resulted in a disease process and associated pathology characteristic of wild-type SIV infection. All animals inoculated with the serially passaged SIVmac239Δnef developed lesions characteristic of wild-type infection, including the occurrence of multiple opportunistic infections and SIV arteriopathy. While mean survival in these animals was longer than that seen in SIVmac239-infected historical controls (1,160 days compared to 529 days, respectively), absolute CD4 count at death was similar (358.8 cells/μl compared to 352.5 cells/μl, respectively) (51). These findings indicate that nef is not an absolute requirement for producing CD4 T-cell depletion and progressive immunodeficiency during simian AIDS.

Two of the four animals infected with serially passaged SIVmacΔ3 developed simian AIDS-defining pathology within the time frames of observation. In both of these animals, there was relative sparing of the absolute peripheral CD4 T-cell number despite the development of SIV arteriopathy and the occurrence of multiple opportunistic infections. While no lesions were noted at necropsy in the two remaining animals, follow-up was limited to 177 and 1,271 days. Data from the serially passaged SIVmac239Δnef-infected animals suggests that the onset of AIDS may be delayed in such animals and longer periods may be required to observe pathological outcomes.

The extent to which the compensatory changes provide functional activities equivalent to those provided by nef or compensate by increasing replicative capacity by some other means remains unclear. The compensatory changes in the cytoplasmic domain of the transmembrane protein gp41 are interesting in a number of respects. The sequence changes in TM are striking in both their number and location. Nef is a myristylated protein predominantly located on the inner surface of the plasma membrane. This is the same general localization as the cytoplasmic domain of TM, where the unusual sequence changes were located. It is thus easy to imagine that the changes could impart on TM functional activities usually borne by Nef. We were not able to demonstrate any increased T-cell-activating properties in the 221 cell assay as a result of the compensatory changes. Possible contributions to surface protein downregulatory activities have not been investigated.

The cytoplasmic domains of SIV, HIV, and other lentiviruses are unusually long (>150 amino acids); although their contributions have not been entirely defined, it seems possible that they could accommodate new or alternative functional activities. A tyrosine residue that is part of a YRPV sequence (nucleotide 8765 in Fig. 3A) serves as an endocytosis signal for regulating the amount of envelope protein on the surface of cells (44, 59). In monkeys infected with a mutant SIV in which this tyrosine was eliminated, the virus appeared to compensate by sequence changes in the conserved SSPPS sequence that is located just downstream (27), sequence changes that are identical or very similar to the ones found in our studies reported here. The significance of the independent appearance of these unusual sequence changes in two very different settings is currently not clear.

Progressive deletion of nef-U3 sequences has been observed previously in monkeys infected with SIV deleted of nef (41) and in a human infected with HIV-1 deleted of nef (40). One possible explanation is that these sequences function predominantly or exclusively as nef coding sequences; in the absence of a functioning nef gene, they may no longer be needed by the virus (34). Since these U3 sequences are present in both LTRs, the sequences that become deleted represent about 6% of the proviral genome. It is not known to what extent reverse transcription may be rate limiting in vivo or whether a growth advantage imparted by a 6% shorter genome can explain the compensatory contribution of the U3 deletion described in this report. A mutant with 101 third-base changes through this region of U3 that overlaps nef in wild-type SIV239 produced wild-type viral loads without reversions upon experimental monkey infection (34). Thus, this mutagenesis study revealed no cis-acting regulatory elements, negative or otherwise, in this U3 region that were significant enough to impact viral loads detectably.

The SIV239Δnef strain in our infected monkeys shows no propensity to put nef back in frame (41). Our SIV239Δnef strain consistently lost long stretches of the nef-U3 overlap region (41; this paper). This contrasts with the work of Sawai et al. (61), who reported a propensity to restore expression of a marginally truncated Nef protein, which was in turn linked to increased pathogenic potential. Although we cannot be certain of the reasons for the differences, they almost certainly relate to differences in the constructs that were used. Importantly, our deletion (39, 41) was 182 bp; the deletion of Sawai et al. (61) was only 152 bp. There are also other differences in the nature of the constructs. The consistent accumulation of large deletions in the region of the nef-U3 overlap when the Δnef version missing 182 bp was used is a strong argument against restoration of normal nef function when this strain is used.

In contrast to SIVmac, HIV-1 naturally has two NF-κB binding elements. Duplication of NF-κB binding elements has been observed previously in SIV in the macaque passages that led to the acutely lethal variant SIVpbj14 (22). The presence of two binding sites for the transcription factor NF-κB would of course be expected to increase the efficiency of transcriptional initiation from the proviral genome. However, deletion of the single NF-κB binding site from both LTRs of SIVmac239 had little or no impact on viral loads (35).

There is little current interest in the practical application of live attenuated virus for use as an AIDS vaccine in humans. Nonetheless, continued research is warranted for what it can teach us about pathogenesis and as preparation for potential use in years or decades to come. Our current studies provide definition to the inherent dangers of live vaccine approaches based principally on the deletion of nef.

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Czajak and Hannah Sanford for expert technical assistance and Michael Piatak, Jr., for performance of the viral load measurements. We also thank the staff of the Division of Primate Resources at NERPRC for assistance in the acquisition of rhesus monkeys and for sampling and care and the Division of Comparative Pathology at NERPRC for assembly of necropsy reports.

This work was supported by PHS grants AI35365, AI25328, and RR00168. This work was also funded in part with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract N01-C0-12400 (J.L.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aiken, C., J. Konner, N. Landau, M. E. Lenburg, and D. Trono. 1994. Nef induces CD4 endocytosis: requirement for a critical dileucine motif in the membrane-proximal CD4 cytoplasmic domain. Cell 76:853-864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aiken, C., and D. Trono. 1995. Nef stimulates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 proviral DNA synthesis. J. Virol. 69:5048-5056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alexander, L., Z. Du, M. Rosenzweig, J. U. Jung, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. A role for natural simian immunodeficiency virus and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef alleles in lymphocyte activation. J. Virol. 71:6094-6099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander, L., R. S. Veazey, S. Czajak, M. DeMaria, M. Rosenzweig, A. A. Lackner, R. C. Desrosiers, and V. G. Sasseville. 1999. Recombinant simian immunodeficiency virus expressing green fluorescent protein identifies infected cells in rhesus monkeys. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 15:11-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander, L., E. Weiskopf, T. C. Greenough, N. C. Gaddis, M. R. Auerbach, M. H. Malim, S. J. O'Brien, B. D. Walker, J. L. Sullivan, and R. C. Desrosiers. 2000. Unusual polymorphisms in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 associated with nonprogressive infection. J. Virol. 74:4361-4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Almond, N., K. Kent, M. Cranage, E. Rud, B. Clarke, and E. J. Stott. 1995. Protection by attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus in macaques against challenge with virus-infected cells. Lancet 345:1342-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baba, T. W., Y. S. Jeong, D. Pennick, R. Bronson, M. F. Greene, and R. M. Ruprecht. 1995. Pathogenicity of live, attenuated SIV after mucosal infection of neonatal macaques. Science 267:1820-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baba, T. W., V. Liska, A. H. Khimani, N. B. Ray, P. J. Dailey, D. Penninck, R. Bronson, M. F. Greene, H. M. McClure, L. N. Martin, and R. M. Ruprecht. 1999. Live attenuated, multiply deleted simian immunodeficiency virus causes AIDS in infant and adult macaques. Nat. Med. 5:194-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benichou, S., M. Bomsel, M. Bodéus, H. Durand, M. Douté, F. Letourneur, J. Camonis, and R. Benarous. 1994. Physical interaction of the HIV-1 nef protein with β-COP, a component of non-clathrin-coated vesicles essential for membrane traffic. J. Biol. Chem. 48:30073-30076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benson, E., A. Sanfridson, J. S. Ottinger, C. Doyle, and B. R. Cullen. 1993. Downregulation of cell-surface CD4 expression by simian immunodeficiency virus nef prevents viral super infection. J. Electron Microsc. 177:1561-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns, D. P. W., and R. C. Desrosiers. 1991. Selection of genetic variants of simian immunodeficiency virus in persistently infected rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 65:1843-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celma, C. C., J. M. Manrique, J. L. Affranchino, E. Hunter, and S. A. Gonzalez. 2001. Domains in the simian immunodeficiency virus gp41 cytoplasmic tail required for envelope incorporation into particles. Virology 283:253-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakrabarti, L., M. Emerman, P. Tiollais, and P. Sonigo. 1989. The cytoplasmic domain of simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein modulates infectivity. J. Virol. 63:4395-4403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen, G. B., R. T. Gandhi, D. M. Davis, O. Mandelboim, B. K. Chen, J. L. Strominger, and D. Baltimore. 1999. The selective downregulation of class I major histocompatibility complex proteins by HIV-1 protects HIV-infected cells from NK cells. Immunity 10:661-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collette, Y., H. Dutartre, A. Benziane, F. Ramos-Morales, R. Benarous, M. Harris, and D. Olive. 1996. Physical and functional interaction of nef with Lck. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6333-6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collins, K. L., B. K. Chen, S. A. Kalams, B. D. Walker, and D. Baltimore. 1998. HIV-1 Nef protein protects infected primary cells against killing by cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature 391:397-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connor, R. I., D. C. Montefiori, J. M. Binley, J. P. Moore, S. Bonhoeffer, A. Gettie, E. A. Fenamore, K. E. Sheridan, D. D. Ho, P. J. Dailey, and P. A. Marx. 1998. Temporal analyses of virus virus replication, immune responses, and efficacy in rhesus macaques immunized with a live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccine. J. Virol. 72:7501-7509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cranage, M. P., A. M. Whatmore, S. A. Sharpe, N. Cook, N. Polyanskaya, S. Leech, J. D. Smith, E. W. Rud, M. J. Dennis, and G. A. Hall. 1997. Macaques infected with live attenuated SIVmac are protected against superinfection via the rectal mucosa. Virology 229:143-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel, M. D., F. Kirchhoff, S. C. Czajak, P. K. Sehgal, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1992. Protective effects of a live-attenuated SIV vaccine with a deletion in the nef gene. Science 258:1938-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Desrosiers, R. 2001. Nonhuman lentiviruses, p. 2095-2122. In D. Knipe and P. Howley (ed.), Field's virology, 4th ed., vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 21.Desrosiers, R. C., J. D. Lifson, J. S. Gibbs, S. C. Czajak, A. Y. M. Howe, L. O. Arthur, and R. P. Johnson. 1998. Identification of highly attenuated mutants of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 72:1431-1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dewhurst, S., J. E. Embretson, D. C. Anderson, J. I. Mullins, and P. N. Fultz. 1990. Sequence analysis and acute pathogenicity of molecularly cloned SIVsmmPBj14. Nature 345:636-640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du, Z., P. O. Ilyinskii, V. G. Sasseville, A. A. Lackner, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1996. Requirements for lymphocyte activation by unusual strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 70:4157-4161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du, Z., S. M. Lang, V. G. Sasseville, A. A. Lackner, P. O. Ilyinskii, M. D. Daniel, J. U. Jung, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1995. Identification of a nef allele that causes lymphocyte activation and acute disease in macaque monkeys. Cell 82:665-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dubay, J. W., S. J. Roberts, B. H. Hahn, and E. Hunter. 1992. Truncation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmembrane glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain blocks virus infectivity. J. Virol. 66:6616-6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freed, E., and M. Ma. 2001. HIV and their replication, p. 1971-2042. In D. Knipe and P. Howley (ed.), Field's virology, vol. 2. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, Pa.

- 27.Fultz, P. N., P. J. Vance, M. J. Endres, Tao Binli, J. D. Dvorin, I. C. Davis, J. D. Lifson, D. C. Montefiori, M. Marsh, M. H. Malim, and J. A. Hoxie. 2001. In vivo attenuation of simian immunodeficiency virus by disruption of a tyrosine-dependent sorting signal in the envelope glycoprotein cytoplasmic tail. J. Virol. 75:278-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabuzda, D. H., A. Lever, E. Terwilliger, and J. Sodroski. 1992. Effects of deletions in the cytoplasmic domain on biological functions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins. J. Virol. 66:3306-3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia, J. V., and A. D. Miller. 1991. Serine phosphorylation-independent downregulation of cell-surface CD4 by nef. Nature 350:508-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbs, J. S., A. A. Lackner, S. M. Lang, M. A. Simon, P. K. Sehgal, M. D. Daniel, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1995. Progression to AIDS in the absence of genes for vpr or vpx. J. Virol. 69:2378-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graziani, A., F. Galimi, E. Medico, E. Cottone, D. Gramaglia, C. Boccaccio, and P. M. Comoglio. 1996. The HIV-1 nef protein interferes with phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation 1. J. Biol. Chem. 271:6590-6593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenway, A., A. Azad, and D. McPhee. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef protein inhibits activation pathways in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and T-cell lines. J. Virol. 69:1842-1850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho, S. N., H. D. Hunt, R. M. Horton, J. K. Pullen, and L. R. Pease. 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension with the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77:51-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ilyinskii, P. O., M. D. Daniel, M. A. Simon, A. A. Lackner, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1994. The role of upstream U3 sequences in the pathogenesis of simian immunodeficiency virus-induced AIDS in rhesus monkeys. J. Virol. 68:5933-5944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ilyinskii, P. O., M. A. Simon, S. C. Czajak, A. A. Lackner, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. Induction of AIDS by simian immunodeficiency virus lacking NF-κB and SP1 binding elements. J. Virol. 71:1880-1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnson, R. P., J. D. Lifson, S. C. Czajak, K. S. Cole, K. H. Manson, R. Glickman, J. Yang, D. C. Montefiori, R. Montelaro, M. Wyand, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1999. Highly attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus protect against vaginal challenge: inverse relation of degree of protection with level of attenuation. J. Virol. 73:4952-4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson, W. E., J. D. Lifson, S. M. Lang, R. P. Johnson, and R. C. Desrosiers. 2003. Importance of B-cell responses for immunological control of variant strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 77:375-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kestler, H., T. Kodama, D. Ringler, M. Marthas, N. Pedersen, A. Lackner, D. Regier, P. Sehgal, M. Daniel, N. King, and R. Desrosiers. 1990. Induction of AIDS in rhesus monkeys by molecularly cloned simian immunodeficiency virus. Science 248:1109-1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kestler, H. W., III, D. J. Ringler, K. Mori, D. L. Panicali, P. K. Sehgal, M. D. Daniel, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1991. Importance of the nef gene for maintenance of high virus loads and for the development of AIDS. Cell 65:651-662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirchhoff, F., T. C. Greenough, D. B. Brettler, J. L. Sullivan, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1995. Absence of intact nef sequences in a long-term survivor with nonprogressive HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 332:228-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kirchhoff, F., H. W. Kestler, I. I. I., and R. C. Desrosiers. 1994. Upstream U3 sequences in simian immunodeficiency virus are selectively deleted in vivo in the absence of an intact nef gene. J. Virol. 68:2031-2037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kodama, T., D. P. Wooley, Y. M. Naidu, H. W. Kestler, I. I. I., M. D. Daniel, Y. Li, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1989. Significance of premature stop codons in env of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 63:4709-4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuiken, C., B. Foley, B. Hahn, P. Marx, F. McCutchan, J. Mellors, J. Mullins, J. Sodroski, S. Wolinsky, and B. Korber. 2000. HIV sequence compendium. Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, N.Mex.

- 44.LaBranche, C. C., M. M. Sauter, B. S. Haggarty, P. J. Vance, J. Romano, T. K. Hart, P. J. Bugelski, M. Marsh, and J. A. Hoxie. 1995. A single amino acid change in the cytoplasmic domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane molecule increases envelope glycoprotein expression on infected cells. J. Virol. 69:5217-5227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lanford, R. E., L. Notvall, D. Chavez, R. White, G. Frenzel, C. Simonsen, and J. Kim. 1993. Analysis of hepatitis C virus capsid, E1, and E2/NS1 proteins expressed in insect cells. Virology 197:225-235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lifson, J. D., J. L. Rossio, M. Piatak, Jr., T. Parks, L. Li, R. Kiser, V. Coalter, B. Fisher, B. M. Flynn, S. Czajak, V. M. Hirsch, K. A. Reimann, J. E. Schmitz, J. Ghrayeb, N. Bischofberger, M. A. Nowak, R. C. Desrosiers, and D. Wodarz. 2001. Role of CD8+ lymphocytes in control of simian immunodeficiency virus infection and resistance to rechallenge after transient early antiretroviral treatment. J. Virol. 75:10187-10199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu, X. L., F. Margottin, S. LeGall, O. Schwartz, L. Selig, R. Benarous, and S. Benichou. 1997. Binding of HIV-1 Nef to a novel thioesterase enzyme correlates with Nef-mediated CD4 downregulation. J. Biol. Chem. 272:13779-13785. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Mammano, F., E. Kondo, J. Sodroski, A. Bukovsky, and H. G. Gottlinger. 1995. Rescue of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 matrix protein mutants by envelope glycoproteins with short cytoplasmic domains. J. Virol. 69:3824-3830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Manninen, A., and K. Saksela. 2002. HIV-1 Nef interacts with inositol trisphosphate receptor to activate calcium signaling in T cells. J. Exp. Med. 195:1023-1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Manrique, J. M., C. C. Celma, J. L. Affranchino, E. Hunter, and S. A. Gonzalez. 2001. Small variations in the length of the cytoplasmic domain of the simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein drastically affect envelope incorporation and virus entry. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 17:1615-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mansfield, K. G., D. Pauley, H. L. Young, and A. A. Lackner. 1995. Mycobacterium avium complex in macaques with AIDS is associated with a specific strain of simian immunodeficiency virus and prolonged survival after primary infection. J. Infect. Dis. 172:1149-1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mariani, R., and J. Skowronski. 1993. CD4 downregulation by nef alleles isolated from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90:5549-5553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Means, R. E., T. Greenough, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. Neutralization sensitivity of cell culture passaged simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 71:7895-7902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naidu, Y. M., H. W. Kestler, I. I. I., Y. Li, C. V. Butler, D. P. Silva, D. K. Schmidt, C. D. Troup, P. K. Sehgal, P. Sonigo, M. D. Daniel, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1988. Characterization of infectious molecular clones of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVmac) and human immunodeficiency virus type 2: persistent infection of rhesus monkeys with molecularly cloned SIVmac. J. Virol. 62:4691-4696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niederman, T. M., W. R. Hastings, S. Luria, and L. Ratner. 1993. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef protein inhibits NF-κB induction in human T cells. Virology 194:338-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Norley, S., B. Beer, D. Binninger-Schinzel, C. Cosma, and R. Kurth. 1996. Protection from pathogenic SIVmac challenge following short-term infection with a nef-deficient attenuated virus. Virology 219:195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Regier, D. A., and R. C. Desrosiers. 1990. The complete nucleotide sequence of a pathogenic molecular clone of simian immunodeficiency virus. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 6:1221-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saksela, K., G. Cheng, and D. Baltimore. 1995. Proline-rich (PxxP) motifs in HIV-1 nef bind to SH3 domains of a subset of Src kinases and are required for the enhanced growth of nef+ viruses but not for downregulation of CD4. EMBO J. 14:484-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sauter, M. M., A. Pelchen-Matthews, R. Bron, M. Marsh, C. C. LaBranche, P. J. Vance, J. Romano, B. S. Haggarty, T. K. Hart, W. M. Lee, and J. A. Hoxie. 1996. An internalization signal in the simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein cytoplasmic domain modulates expression of envelope glycoproteins on the cell surface. J. Cell Biol. 132:795-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sawai, E. T., A. Baur, H. Struble, B. M. Peterlin, J. A. Levy, and C. Cheng-Mayer. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef associates with a cellular serine kinase in T lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:1539-1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sawai, E. T., M. S. Hamza, M. Ye, K. E. Shaw, and P. A. Luciw. 2000. Pathogenic conversion of live attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus vaccines is associated with expression of truncated Nef. J. Virol. 74:2038-2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schrager, J. A., and J. W. Marsh. 1999. HIV-1 Nef increases T-cell activation in a stimulus-dependent manner. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:8167-8172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwartz, O., V. Marechal, O. Danos, and J. M. Heard. 1995. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef increases the efficiency of reverse transcription in the infected cell. J. Virol. 69:4053-4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schwartz, O., V. Marechal, S. LeGall, F. Lemonnier, and J.-M. Heard. 1996. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 nef protein. Nat. Med. 2:338-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shacklett, B. L., C. Denesvre, B. Boson, and P. Sonigo. 1998. Features of the SIVmac transmembrane glycoprotein cytoplasmic domain that are important for Env functions. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 14:373-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Simmons, A., V. Aluvihare, and A. McMichael. 2001. Nef triggers a transcriptional program in T cells imitating single-signal T-cell activation and inducing HIV virulence mediators. Immunity 14:763-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Skowronski, J., D. Parks, and R. Mariani. 1993. Altered T-cell activation and development in transgenic mice expressing the HIV-1 nef gene. EMBO J. 12:703-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Spina, C. A., T. J. Kwoh, M. Y. Chowers, J. C. Guatelli, and D. D. Richman. 1994. The importance of nef in the induction of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication from primary quiescent CD4 lymphocytes. J. Electron Microsc. 179:115-123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Suryanarayana, K., T. A. Wiltrout, G. M. Vasquez, V. M. Hirsch, and J. D. Lifson. 1998. Plasma SIV RNA viral load by determination by real-time quantification of product generation in reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 14:183-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang, J. K., E. Kiyokawa, E. Verdin, and D. Trono. 2000. The Nef protein of HIV-1 associates with rafts and primes T cells for activation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:394-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wyand, M. S., K. Manson, D. C. Montefiori, J. D. Lifson, R. P. Johnson, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1999. Protection by live, attenuated simian immunodeficiency virus against heterologous challenge. J. Virol. 73:8356-8363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wyand, M. S., K. H. Manson, M. Garcia-Moll, D. Montefiori, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1996. Vaccine protection by a triple deletion mutant of simian immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 70:3724-3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wyand, M. S., K. H. Manson, A. A. Lackner, and R. C. Desrosiers. 1997. Resistance of neonatal monkeys to live attenuated vaccine strains of simian immunodeficiency virus. Nat. Med. 3:32-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]