Abstract

As it descended from Escherichia coli O55:H7, Shiga toxin (Stx)-producing E. coli (STEC) O157:H7 is believed to have acquired, in sequence, a bacteriophage encoding Stx2 and another encoding Stx1. Between these events, sorbitol-fermenting E. coli O157:H− presumably diverged from this clade. We employed PCR and sequence analyses to investigate sites of bacteriophage integration into the chromosome, using evolutionarily informative STEC to trace the sequence of acquisition of elements encoding Stx. Contrary to expectations from the two currently sequenced strains, truncated bacteriophages occupy yehV in almost all E. coli O157:H7 strains that lack stx1 (stx1-negative strains). Two truncated variants were determined to contain either GTT or TGACTGTT sequence, in lieu of 20,214 or 18,895 bp, respectively, of the bacteriophage central region. A single-nucleotide polymorphism in the latter variant suggests that recombination in that element extended beyond the inserted octamer. An stx2 bacteriophage usually occupies wrbA in stx1+/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7, but wrbA is unexpectedly unoccupied in most stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains, the presumed progenitors of stx1+/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole promotes the excision of all, and ciprofloxacin and fosfomycin significantly promote the excision of a subset of complete and truncated stx bacteriophages from the E. coli O157:H7 strains tested; bile salts usually attenuate excision. These data demonstrate the unexpected diversity of the chromosomal architecture of E. coli O157:H7 (with novel truncated bacteriophages and multiple stx2 bacteriophage insertion sites), suggest that stx1 acquisition might be a multistep process, and compel the consideration of multiple exogenous factors, including antibiotics and bile, when chromosome stability is examined.

Shiga toxins 1 and 2 (Stx1 and Stx2) are cardinal virulence factors of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Stx1 is nearly identical to Stx, the principal extracellular cytotoxin of Shigella dysenteriae serotype 1 (8). Stx2 has 56% identity to Stx1 (36). The stx1 and stx2 A and B subunit genes exist as tandem open reading frames (ORFs) in the central portion of lambdoid bacteriophages in E. coli O157:H7 (19). In Sakai and EDL933, the two E. coli O157:H7 strains that have been completely sequenced, the bacteriophage that encodes Stx1 is integrated into yehV (57), which encodes a protein that positively regulates curli expression (7), and is flanked by duplications of CCCTGTCACGTTACGCGCGTG. The bacteriophage that encodes Stx2 is integrated into wrbA (32, 40), which encodes a novel multimeric flavodoxin-like protein (13), and is flanked by duplications of GACATATTGAAAC. Almost all E. coli O157:H7 strains possess stx2, and approximately three-quarters contain, in addition, stx1 (strains lacking stx1 are referred to hereafter as stx1-negative strains) (23, 38, 45). Most human non-O157:H7 Stx-producing E. coli (STEC) strains possess stx1 but lack stx2 (5, 6, 28, 51). Except for an Stx2e-encoding bacteriophage which is known to be integrated into yecE in STEC ONT:H− (42), the insertion sites of stx bacteriophages have not yet been identified in the chromosomes of non-O157:H7 STEC strains (25, 29, 47).

Multilocus enzyme electrophoresis analysis (53), colony hybridizations, Southern blotting, and PCRs with primers specific for stx genes teach that E. coli O157:H7 descended from E. coli O55:H7 or from a similar common progenitor (11). E. coli O55:H7 and STEC belonging to serogroup O157 form a clade termed the STEC 1 (or enterohemorrhagic E. coli 1) group (52). The currently accepted evolutionary model suggests that in its descent from E. coli O55:H7, E. coli O157:H7 lost the O55 rfb-gnd cluster and acquired the stx2 bacteriophage and the O157 rfb-gnd cluster (4, 46, 50). Subsequently, sorbitol-fermenting stx2+ E. coli O157 (11, 15) separated from this lineage. After these two lineages diverged, E. coli O157:H7 acquired stx1 (11), presumably via acquisition of the bacteriophage that contained this gene, and lost the ability to ferment sorbitol, while the sorbitol-fermenting stx2+ E. coli O157 evolved into nonmotile E. coli O157:H−. Most non-O157:H7 STEC strains associated with human diseases are distantly related to E. coli O157:H7 and form a clade termed the STEC 2 (or enterohemorrhagic E. coli 2) group (54).

The bacteriophage insertion sites in the STEC 1 group have not been examined systematically to confirm the validity of or to refine our presumed understanding of the sequence of acquisition of the elements containing the stx genes. The recent releases of the sequences and insertion sites of the stx bacteriophages from two different E. coli O157:H7 strains (16, 39) prompted us to investigate these sites in diverse STEC 1 organisms. This study was performed to determine if, as predicted, stx bacteriophages occupied wrbA and yehV consecutively as this lineage evolved and to determine if stx bacteriophages utilize these two integration sites outside the STEC 1 lineage. Additionally, we assessed the stability of the integration of the stx bacteriophages into the E. coli O157:H7 chromosome in selected strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria and growth conditions.

Organisms studied are listed in Table 1. Frozen bacterial stocks were inoculated directly into Luria broth (LB; 4 ml) (43). Broths were prewarmed to 37°C if they were used as starter cultures, until an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8 was attained, at which time 300 μl was added to 3 ml of prewarmed LB with or without subinhibitory concentrations of ciprofloxacin (2 μg/liter; Bayer Corporation, West Haven, Conn.), trimethoprim (4 μg/liter)-sulfamethoxazole (20 μg/liter) (TMP-SMX; Elkins-Sinn, Cherry Hill, N.J.), or ampicillin (200 μg/liter; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Fosfomycin assimilation by E. coli depends on induction of the glycerol phosphate or hexose phosphate transport system (24). Therefore, we used LB containing an inducer of the former system, glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P; 50 mg/liter), with and without added fosfomycin (1.6 mg/liter; Sigma), to study this antibiotic's effects. The influences of all antibiotics on bacteriophage integrations were studied in broths with or without bile salts (1.5 g of an equal mix of sodium cholate and sodium deoxycholate/liter [item no. B8756; Sigma]). For chromosomal structural analyses, bacteria from broths grown overnight after direct inoculation from frozen stocks were studied. All broths were incubated (16 h, 37°C) without agitation before genomic DNA was extracted with the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany).

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Organism | Reference or source | stx1f | yehVg | stx2f | wrbAg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STEC 1 lineage | |||||

| O55:H7 | |||||

| TB156A, TB182Aa,b | 6 | − | I | − | I |

| 5A, 5B, 5C, 5D | 4 | ||||

| 5Ec | 4 | − | O | − | I |

| O157:H7 | |||||

| 84-01,a,b 87-01, 87-20a,b | 43 | + | O | + | O |

| 93-111 | 3 | ||||

| EK3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22, 24, 25, 26 | 26 | ||||

| U3, 4, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 19, 21, 22, 34, 26, 28, 30, 31, 34, 35, 36, 40, 41, 43, 44, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, P1, 4, 6, 9, 10, H2 | 8 | ||||

| 86-24,d 86-28,d 86-17,e 87-07e | 43 | − | O | + | O |

| EK15, 28 | 26 | ||||

| U39 | 8 | ||||

| 87-14 | 43 | − | O | + | I |

| EK1,b 2, 18,b 19,b 23, 27 | 26 | ||||

| U2, 5, 7, 11, 16, 17, 18, 20, 24, 29, 32, 33, 42, 45,d 51, 52, P3, 7, H4, 5 | 8 | ||||

| P8 | 8 | − | I | + | O |

| Sorbitol-fermenting O157:H− | |||||

| CB2755b | Lothar Beutin | − | I | + | O |

| 493/89 | 13 | ||||

| Non-STEC 1 lineage | |||||

| Non-O157:H7 | |||||

| TB352A (O26:NM), TB334C (O85:NM), TB285A (O126:H2), TB154A (O103:H6) | 6 | + | I | − | I |

| EK30, 31, 32, 33 (O103:H2), EK34 (O111:nonmotile), EK35 (O111:H8), EK36, 37 (O118:H16), EK39 (Orough:H11) | 26 | ||||

| EK38 (O121:H19) | 26 | − | I | + | I |

| TB226A (O111:HN) | 6 | + | I | + | I |

Amplicons in yehV in this strain have been sequenced.

Amplicons in wrbA in this strain have been sequenced.

Left end of bacteriophage occupies yehV; right end of bacteriophage not detected at this junction.

Strain has Δ20,214 bacteriophage.

Strain has Δ18,895 bacteriophage.

+, present; −, absent.

I, intact; O, occupied.

PCR conditions.

We amplified fragments shorter than 1.5 kb in 50-μl volumes containing 10× PCR buffer (5 μl; Promega, Madison, Wis.), 10 ng of bacterial or 5 μl of reconstituted phage pellet DNA, MgCl2 (1.5 mM), deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP; final concentration of each nucleotide, 200 μM), primers (final concentration of each, 1 μM) (Table 2), and Taq DNA polymerase (1.25 U; Promega) in an iCycler (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.). The following cycling conditions were employed: 4 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s (94°C), 30 s (58°C), and 90 s (72°C) and a final 7-min elongation step (72°C). We amplified longer segments by using Herculase Enhance Taq DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) in 50 μl containing 300 ng of target DNA in 5 μl of 10× Herculase buffer (Stratagene), dNTP (400 μM [each]), and primers (final concentration of each oligonucleotide, 2 μM) (Table 2). For these amplifications, we used the following conditions: 10 cycles at 92°C (30 s), 58°C (30 s), and 68°C (1 min per kb of target) followed by 20 cycles at 92°C (30 s), 58°C (30 s), and 68°C (1 min per kb of target with an increment of 10 s each cycle) and a final elongation step (68°C, 10 min). Amplification products were separated in Tris-borate-EDTA agarose gels, ethidium stained, and photographed.

TABLE 2.

Primer pairs used in this study

| Primer pair | Sequence (5′ → 3′) | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| A | AAGTGGCGTTGCTTTGTGAT | Amplicon spans stx1 bacteriophage insertion site yehV |

| B | AACAGATGTGTGGTGAGTGTCTG | |

| C | AGGAAGGTACGCATTTGACC | Amplicon spans stx2 bacteriophage insertion site wrbA |

| D | CGAATCGCTACGGAATAGAGA | |

| A | AAGTGGCGTTGCTTTGTGAT | Amplicon spans bacteriophage-yehV right junction |

| E | GATGCACAATAGGCACTACGC | |

| F | CACCGGAAGGACAATTCATC | Amplicon spans bacteriophage-yehV left junction |

| B | AACAGATGTGTGGTGAGTGTCTG | |

| C | AGGAAGGTACGCATTTGACC | Amplicon spans bacteriophage-wrbA right junction |

| G | ATCGTTCGCAAGAATCACAA | |

| H | CCGACCTTTGTACGGATGTAA | Amplicon spans bacteriophage-wrbA left junction |

| D | CGAATCGCTACGGAATAGAGA | |

| I | GTTATCCGTCAGCACCTTGTAGA | Primer sites span truncations in stx1 bacteriophage |

| J | ATATCCGTACTCCTGGCCTTAAC | |

| Ka | CGCTTTGCTGATTTTTCACA | stx1 |

| L | GTAACATCGCTCTTGCCACA | |

| Ma | GTTCCGGAATGCAAATCAGT | stx2 |

| N | CGGCGTCATCGTATACACAG | |

| O | TGACCACACGCTGACGCTGACCA | malB |

| P | TTACATGACCTCGGTTTAGTTCACAGA |

Primer pair described in reference 28.

Sequencing.

Selected amplicons were cloned into the pCR4 TOPO vector (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, Calif.) and sequenced by using the PE Applied Biosystems (Foster City, Calif.) kit and an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Homology searches were performed on a National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST server (12).

Segment excision proportions (SEPs).

The proportions of intact bacteriophage insertion sites in DNA extracted after overnight culture were calculated for selected E. coli O157:H7 strains grown in various media by using a LightCycler Real Time PCR cycler (Bio-Rad). Primer pairs A-B and C-D were used to produce amplicons that spanned the insertion sites, and primer pairs A-E, F-B, C-G, and H-D were used to produce amplicons that spanned the junctions between the bacteriophages and chromosomes (Table 2). These primers were used in 1 μM final concentrations in 25 μl of PCR mixture containing bacterial DNA (10 ng), MgCl2 (1.5 mM), dNTP (final concentration of each nucleotide, 200 μM), Taq DNA polymerase (1.25 U), and 10× SYBR Green PCR buffer (2.5 μl; PE Biosystems, Warrington, United Kingdom).

SEPs were calculated according to the following formula: SEP = X/[X + (Y + Z)/2], where X is the number of copies per unit of volume of the target DNA spanning the insertion sites and Y and Z are the numbers of copies per unit of volume corresponding to amplicons spanning the right and left bacteriophage-chromosome junctions, respectively. The number of copies per microliter was derived by dividing the product of 6.02 × 1023 (copies per mole) and the concentration (grams per microliter) by the molecular mass, where molecular mass (grams per mole) = (number of base pairs × 660 Da/bp) and 1 mol is equal to 6 × 1023 molecules (i.e., the number of copies). SEPs were quantified in quadruplicate on two separate days. In each experiment, a standard curve was derived by using a recombinant plasmid consisting of the pCR4 TOPO vector into which an amplicon generated by primers I and J was cloned; concentrations used in the standard curve ranged between 1 and 1010 copies/μl.

Statistics.

We used analysis of variance to test for equality of means among the 12 conditions and Tukey's method for multiple comparisons for the pairwise comparison of means (35).

Phage extractions from culture supernatants.

Chloroform (50 μl) was added to aspirated supernatants from centrifuged (5,000 × g, 4°C, 10 min) 3-ml broth cultures; resulting suspensions were shaken (120 rpm, room temperature, 10 min) and centrifuged (4,000 × g, room temperature, 10 min). The supernatant was removed and incubated (37°C, 30 min) after the addition of DNase I (2 U/ml; Ambion, Austin, Tex.) and RNase A1 (10 μg/ml; Ambion). Phage particles were then precipitated overnight on ice by adding NaCl (1 M final concentration) and polyethylene glycol 8000 (to 10% [wt/vol]), followed by centrifugation (10,000 × g, 4°C, 20 min). The pellet was suspended in 500 μl of 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) containing MgCl2 (10 mM) and NaCl (100 mM) before being extracted twice with equal volumes of chloroform. The chloroform-extracted supernatant was again treated with DNase I (10 U in 500 μl, 37°C, 30 min) to digest noncoated bacterial DNA. The phage particles were then disrupted by adding phenol (500 μl), and liberated DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform (1:1) and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1) and precipitated on ice with 3 M sodium acetate (0.1 volume) and chilled absolute ethanol (2 volumes, 20 min). Precipitated DNA was then centrifuged (12,000 × g, 4°C, 5 min), and pellets were washed (70% ethanol), dried, and resuspended in 100 μl of Tris-EDTA (pH 8.0).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The newly determined sequence was deposited in GenBank under accession number AY160192-5.

RESULTS

Bacteriophage insertions in yehV and wrbA.

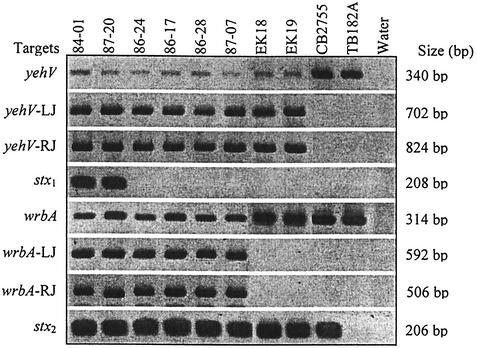

As expected, the stx1 bacteriophage insertion site in yehV was unoccupied in most (six of the seven) E. coli O55:H7 strains tested (Table 1 and Fig. 1); the only exception was strain 5E, in which the left junction of a bacteriophage was found in yehV. Also as expected, yehV was uninterrupted in sorbitol-fermenting E. coli O157:H−. The sequences of the amplicons spanning this locus confirmed that neither bacteriophage nor other inserted DNA disrupts this locus, and duplicated flanking sequences are not present. Also as predicted, wrbA is intact in ancestral E. coli O55:H7 but is occupied by a bacteriophage in E. coli O157:H−, as it is in each of the two E. coli O157:H7 strains that have been sequenced (16, 32, 39, 40, 57).

FIG. 1.

Amplicons for investigation of the yehV and wrbA integration sites in E. coli O157:H7. Bacterial strains used, loci examined, and lengths of resulting amplicons are listed across the top and to the left and right of the rows of amplicons, respectively. LJ, left junction; RJ, right junction.

However, contrary to expectations, bacteriophage sequences disrupt yehV at the insertion site used by stx1 bacteriophages in 34 of 35 stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains tested (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Also unexpectedly, wrbA is intact in 27 of these 35 isolates. Amplicons suggesting intact wrbA in three stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains were sequenced, and the gene was confirmed as ancestral and unoccupied, without duplicated GACATATTGAAAC sequences flanking the insertion site.

Analysis of DNA occupying yehV in stx1-negative E. coli O157:H7.

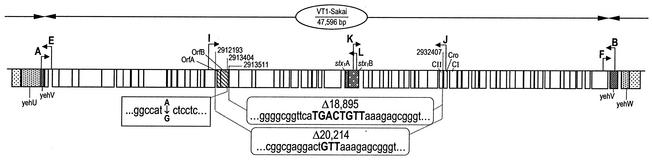

Four stx1-negative E. coli O157:H7 strains were chosen for extended analysis of the occupied yehV site, and the structural details of the occupying DNA are provided in Fig. 2. In strains 86-24 and 86-28, GTT is present in lieu of 20,214 bp and 31 complete ORFs that exist in VT1-Sakai (32) (for purposes of simplicity, all positions are related to those in the sequenced Sakai strain, though the same findings also apply to the stx1 bacteriophage in strain EDL933). In strains 86-17 and 87-07, TGACTGTT takes the place of 18,895 bp. This missing 18,895-bp segment comprises 28 complete ORFs and one partial ORF, Ecs 2960, which encodes a putative protease/scaffold protein. We have termed these truncated structures the Δ20,214 and Δ18,895 bacteriophages, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Structures of two forms of truncated bacteriophages of stx1-negative E. coli O157:H7. Inserted GTT and TGACTGTT sequences replace segments that are found in truncated stx1 bacteriophages in two sequenced strains. ORF borders, proportions, and designations and nucleotide positions relate to those in reference 16. An A→G SNP 108 nucleotides 5′ to the octamer in both sequenced Δ18,895 bacteriophages and primer locations used to generate data pertaining to stx1 bacteriophages are noted. A, E, I, K, L, J, F, and B are primers.

In the Δ20,214 bacteriophage, 114- and 198-bp hybrid ORFs (HOs) are created from two smaller ORFs that are unregistered in the Sakai database. The octamer in the Δ18,895 bacteriophage gives rise to three HOs that do not exist in VT1-Sakai (Table 3). The trimer in the Δ20,214 bacteriophage engenders two HOs. None of these five HOs has extensive homology to genes in the database.

TABLE 3.

HOs in truncated bacteriophages that are not present in VT1-Sakai

| Bacteriophage (strains) | HOa | Start codone | Stop codone | No. of amino acids in putative corresponding proteins |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ20,214 (86-24,a 86-28b) | HO-T1 | 2912159 | 2932402 (TAA) | 37 |

| HO-T2 | 2932460 | 2912053 (TGA) | 65 | |

| Δ18,895 (86-17,c 87-07d) | HO-T3 | 2913402 | 2932408 (TAA) | 39 |

| HO-T4 | 2913511 (+T)f | 2913276 (TGA) | 78 | |

| HO-T5 | 2932460 | 2913472 (TGA) | 33 |

The trimer and octamer shown in Fig. 2 have identical regions 3′ to their borders, including genes encoding the putative prophage repressor C1 and the regulator Cro, which are involved in phage immunity. The gene encoding regulator protein CII, a third probable immunity molecule in the complete stx1 bacteriophage, is absent from both truncated forms. Homologues to putative transposases OrfA and OrfB of IS629 are in proximity to HO-T4 in the Δ18,895 bacteriophage, but these OrfA and OrfB homologues are not found in the Δ20,214 bacteriophage. The octamer's 5′ border is adjacent to the inverted repeat at the right end of the IS629 homologue.

The two Δ18,895 bacteriophages each contain an A→G single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in ORF Ecs 2959, 108 nucleotides from the 5′ border of the TGACTGTT octamer. Interestingly, a GACT sequence in the Δ20,214 bacteriophage that is also found in VT1-Sakai is adjacent to the GTT that is found in lieu of the missing 20,214 nucleotides, producing a heptamer that is identical to seven of the eight nucleotides in the octamer.

Analysis of yehV and wrbA in non-O157:H7 STEC.

In each of 15 non-O157:H7 strains examined, the insertion sites in yehV and wrbA are intact, and these genes do not contain bacteriophage-chromosome junctions. Thus, as those of STEC ONT:H− (42), these elements integrate into the chromosomes at positions other than those utilized in the sequenced stx1+/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains.

Excision of bacteriophages from the chromosomes of E. coli O157:H7.

Primers spanning complete and truncated bacteriophage insertion sites in E. coli O157:H7 elicit from bacterial DNA faint PCR products that are the sizes that would be expected had these genes been intact (Fig. 1). The presence of these faint bands suggests that a subset of the bacteria in these broths have chromosomes that no longer contain inserted elements. These primers do not elicit amplicons with sterile broth as a target (data not shown). Primers spanning the chromosome-bacteriophage junctions produce amplicons that are considerably more abundant than those that span the insertion sites. Amplicon sequences across the yehV and wrbA insertion sites in selected strains (Table 1) demonstrate that an intact gene is regenerated from a site that has been formerly occupied. Thus, intact and truncated bacteriophages are excised from the E. coli O157:H7 chromosome at discernible frequencies, and the excisions generate ancestral integration sites in the chromosome.

Antibiotics, bile salts, and excision of stx bacteriophages.

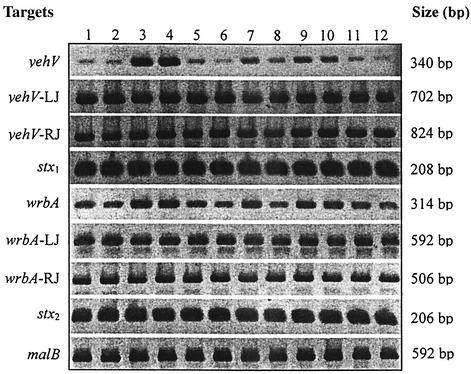

TMP-SMX significantly increased the proportion of intact yehV and wrbA sites in all E. coli O157:H7 strains tested, whether the occupying bacteriophage was complete or truncated. Ciprofloxacin and fosfomycin significantly increased SEPs at yehV and wrbA in most strains and in some strains, respectively. Bile salts usually significantly attenuated the increased SEPs (Fig. 3 and Table 4). There was no indication that either of the chromosome-bacteriophage junctions were preferentially amplified, thereby distorting the SEP; the intraisolate copy numbers of junctional amplicons were within 97% of each other in >99% of the determinations.

FIG. 3.

Amplicons elicited across integration sites, in response to antibiotics and bile salts. E. coli O157:H7 strain 87-20 was grown in LB without (lanes 1 and 2) or with (lanes 3 and 4) TMP-SMX, ciprofloxacin (lanes 5 and 6), or ampicillin (lanes 7 and 8) or in LB with G-6-P without (lanes 9 and 10) or with (lanes 11 and 12) fosfomycin. Samples in even-number lanes were grown in bile salts. Loci examined and lengths of resulting amplicons are listed to the right and left of the rows. LJ, left junction; RJ, right junction.

TABLE 4.

SEPs across yehV and wrbA after growth in LB with various additivesa

| Locus | Strain | Mean (standard deviation) of SEPsb in:

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB | BS | TMP-SMX | TMP-SMX + BS | CIP | CIP + BS | AMP | AMP + BS | G-6-P | G-6-P + BS | FOS | FOS + BS | ||

| yehV | 84-01 | 2.8 (3.5) | 2.8 (3.5) | 16.9 (19.7) | 7.9 (9.7) | 6.8 (8.3) | 7.1 (9.2) | 2.6 (3.6) | 2.9 (3.9) | 2.6 (4.0) | 2.1 (2.8) | 6.9 (7.4) | 1.5 (1.9) |

| 87-20 | 5.0 (9.8) | 1.3 (1.1) | 38.9 (20.7) | 31.5 (17.7) | 4.7 (3.2) | 3.9 (2.8) | 1.6 (2.0) | 2.0 (3.2) | 1.3 (1.1) | 1.6 (1.8) | 11.2 (7.4) | 6.2 (5.3) | |

| 86-17 | 3.2 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.1) | 13.6 (3.9) | 5.6 (1.2) | 6.8 (2.1) | 3.7 (0.6) | 2.3 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.4) | 8.9 (4.2) | 2.1 (0.8) | |

| 86-24 | 1.6 (1.7) | 0.5 (0.8) | 9.0 (5.8) | 2.3 (2.2) | 3.3 (2.9) | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.2 (1.3) | 0.8 (0.8) | 1.2 (1.4) | 0.8 (0.9) | 2.9 (2.9) | 1.2 (1.3) | |

| wrbA | 84-01 | 29.2 (24.6) | 33.9 (30.1) | 98.3 (79.7) | 62.8 (54.9) | 51.6 (37.1) | 44.2 (37.3) | 34.6 (26.9) | 36.4 (29.3) | 33.3 (27.6) | 34.0 (28.6) | 52.3 (32.7) | 5.4c (5.5) |

| 87-20 | 8.9 (6.7) | 5.0 (3.8) | 99.8 (39.9) | 64.7 (30.3) | 34.9 (14.8) | 20.6 (13.5) | 8.9 (6.3) | 5.7 (4.2) | 8.1 (5.5) | 6.1 (4.6) | 57.8 (27.0) | 23.9 (19.4) | |

Abbreviations: BS, bile salts; CIP, ciprofloxacin; AMP, ampicillin; FOS, fosfomycin.

Proportions were multiplied by 103. Values in bold are significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those for broth without antibiotic. Underlined values indicate that antibiotic effects are significantly (P < 0.05) attenuated by bile salts.

The SEP in bile salts plus antibiotic was significantly (P < 0.05) less than those in corresponding broth with bile salts and corresponding antibiotic without bile salts even though the SEP in broth with antibiotic and without bile salts was not significantly higher than that in corresponding broth.

Appearance of bacteriophage DNA in culture supernatants.

To determine whether bacteriophage excisions result in the appearance of intact bacteriophage in the culture supernatant, we subjected DNase-treated supernatants of stx1+/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains 84-01 and 87-20 and stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains 86-17 and 86-24 to PCR with primer pairs specific for stx1 (K-L) and stx2 (M-N) or truncated stx1 bacteriophages (I-J). In these experiments, organisms were grown in the absence or presence of subinhibitory concentrations of each antibiotic.

DNase-resistant stx1 and stx2, presumably representing phage-coated DNA, appeared in the supernatants of the two stx1+/stx2+ strains. malB amplicons were not elicited from the supernatant, so the stx sequences in the supernatant cannot be attributed simply to bacterial lysis. In contrast, truncated bacteriophage sequences were not amplified from the supernatants of the two stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains tested (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

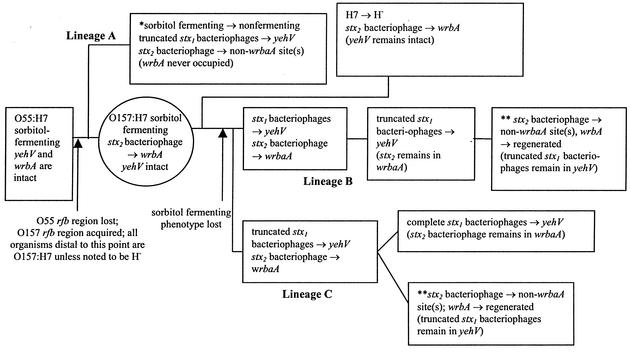

The current model of emergence of toxigenic E. coli O157:H7 from its nontoxigenic, less virulent progenitor, E. coli O55:H7, relies on four crucial sequential events: (i) acquisition of an stx2 bacteriophage in a single event and at a single site (probably wrbA); (ii) splitting off of the clone leading to E. coli O157:H−; (iii) acquisition of the stx1 bacteriophage in a single event and at a single site (probably yehV) by E. coli O157:H7; and (iv) loss of the ability to ferment sorbitol by E. coli O157:H7 (event iv might have preceded event iii during this descent). The data we present confirm this model to the point of emergence of serogroup O157 from serotype O55:H7 and to the point of divergence of the nonmotile sorbitol-fermenting lineage before an stx1 bacteriophage occupied yehV. The only finding that is discordant with this model, prior to these two points in evolution, is our observation that the left junction of a bacteriophage occupies yehV in E. coli O55:H7 strain 5E. However, strain 5E, unlike other tested members of this serotype, possesses iha and other components of a tellurite resistance, adherence-conferring island (44). Thus, in light of its genetic aberrancy, the presence of bacteriophage sequences in yehV in strain 5E is difficult to interpret.

The parsimonious scenario described above explains the emergence of the E. coli O157 serogroup from its nontoxigenic progenitor, but this model must now be modified to accommodate two unanticipated findings in stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains. First, an stx2 bacteriophage occupies wrbA in only a minority of these organisms. This means that the stx2 bacteriophage was inserted into a site or sites other than wrbA in E. coli O157:H7 at multiple different times in history or that intrabacterial mobilizations of the bacteriophage led to vacation of the wrbA insertion locus and entry of the bacteriophage into other places in the chromosome. Second, bacteriophages that are truncated to the extent that they lack, at a minimum, part of stx1 occupy yehV in almost all isolates tested.

Accordingly, we produce in Fig. 4 several new working evolutionary models to help refine present concepts of descent of the STEC 1 clade. In postulated lineage A, stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains in which the stx2 bacteriophage is permanently integrated into a site or sites other than wrbA would constitute a separate branch of the STEC 1 clade, which would have diverged from other E. coli O157:H7 strains before the stx2 bacteriophage became stably integrated into wrbA in postulated lineage B or C. Postulated lineage A also would have sustained independent losses of the sorbitol-fermenting phenotype and acquisitions of bacteriophages that occupy yehV in an evolutionary scenario that parallels the events leading to the emergence of postulated lineages B and C.

FIG. 4.

Evolutionary scenarios. Serotypes, phenotypes, genotypes, critical events, and postulated intermediate form (circle) in three different scenarios leading to the five STEC 1 forms known to exist today (boxes). One asterisk indicates that the sequence of listed events is not known but is presumed to have occurred at different times during evolution. This result would obviate the need for postulated lineage B or C to produce such an organism. Two asterisks indicate that organisms in this box would not exist if lineage A exists.

Serial evolutionary scenarios (postulated lineages B and C) are more likely to have occurred than are parallel scenarios, because they require fewer events leading to extant organisms. With respect to the stx2 bacteriophage, in postulated lineages B and C this element would have entered a sorbitol-fermenting progenitor E. coli O157:H7 strain once and integrated into its chromosome at a single site, probably wrbA. Then, the sorbitol-fermenting O157:H− clone would have diverged. Subsequently,yehV was occupied by either stx1 bacteriophages (postulated lineage B) or truncated variants (postulated lineage C). At a later point, the stx2 bacteriophage vacated its initial integration site and entered one or more additional sites, leading to a common genotype of E. coli O157:H7 existing today but not the genotype represented by the sequenced strains. Each model proposed requires the past existence of a sorbitol-fermenting E. coli O157:H7 intermediate, preferably with an stx2 bacteriophage inserted in wrbA. Such a strain has yet to be found and might be extinct.

Currently available data do not predict whether postulated lineage B is more likely to have occurred than postulated lineage C. In postulated lineage B, stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 descends from stx1+/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7, whereas postulated lineage C has a reverse descent order. In either case, the truncated bacteriophages are either progenitors to or descendants of complete stx1 bacteriophages. The variants' sequences contain several clues that might help discern the origin or destiny of these structures. First, the GACTGTT in the octamer in the Δ18,895 bacteriophage and the GACT that is juxtaposed to the 5′ end of the inserted GTT in the Δ20,214 bacteriophage raise the possibility that one of the truncated bacteriophages descended from the other. Indeed, the mobile DNA in the Δ20,214 bacteriophage could include some or all of the four nucleotides 5′ to the GTT. Additionally, identical nonsynonymous A→G SNPs 108 nucleotides from the 5′ border of each octamer in the two Δ18,895 truncated bacteriophages that we sequenced suggest that the SNPs and the truncations in these strains did not arise independently. Thus, even though the most straightforward mechanism for acquiring or losing stx1 would be the simple exchange of the octamer for stx1 and contiguous DNA, or vice versa, the presence of this SNP suggests that at least one of the borders of recombination leading to the acquisition or loss of stx1 is distal to at least one of the octamer's borders. Indeed, such instructive SNPs in rfbE strongly suggest interlineage cotransfer of large chromosomal segments between E. coli O157:H16 strain 13A81 and E. coli O157:H− strain 3584-91 (46). Also, the juxtaposition of the right end of IS629 and the 5′ terminus of the octamer suggests that a transposon-mediated process has played a role in the evolution of the structures of these bacteriophages. Continued analyses of polymorphisms and genotypes in instructive E. coli O157:H7 strains should refine our understanding of the emergence of E. coli O157:H7.

While the two HOs in the Δ20,214 bacteriophage arise through the GTT trimer's bridging of parts of two ORFs in the Sakai genome, the genesis of the three HOs in the Δ18,895 bacteriophage is not so straightforward and warrants additional comment. HO-T3 results from the A→G SNP, because the G gives rise to an ATG start codon not found in the Sakai sequence. The A opposite the 5′ T in the TGACTGTT octamer, which creates a start codon that is not found in the Sakai strain, engenders HO-T4. The functions of these HOs are unknown.

Ohnishi et al. (37) recently reported that in six of eight unrelated stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strains, the Sp5 bacteriophage (their designation for the stx2 bacteriophage) does not occupy wrbA, its site of integration in the sequenced VT1-Sakai and 933W strains. Our data confirm these particular findings and extend them to a larger set of strains from North America. Our data differ, however, in relation to the frequencies of utilization of yehV by the stx1 bacteriophage. Whereas yehV was occupied by an stx1 bacteriophage in each of the 58 stx1+ E. coli O157:H7 strains that we studied, Ohnishi et al. provide data that the stx1 bacteriophage integrates into other loci in two of the seven stx1+ E. coli O157:H7 strains from Japan that they examined.

Two bacteriophage immunity genes, cro and C1, that remain in the truncated bacteriophages might prevent replication of similar bacteriophages (10). Therefore, if the truncated bacteriophages are progenitors of the complete stx1 bacteriophage, stx1 and flanking regions might have been acquired from an element that is unrelated to the stx1 bacteriophage. Indeed, bacteriophages plausibly acquire segments from a vast pool of related and unrelated bacteriophages (17). In 1987, Huang et al. (19) suggested that had stx1 been acquired via fortuitous removal from a donor chromosome during imprecise prophage excision, this gene would have been located closer to one of the attachment sites; its location in the central portion of the bacteriophage suggests that the acquisition of stx1 involved deletions and duplications during evolution. The presence of truncated stx1 bacteriophages in stx1-negative E. coli O157:H7 lends support to their proposal.

Our data also shed light on the effects of exogenous factors on chromosome stability in E. coli O157:H7. Mitomycin C increases the number of copies of stx genes (20) and stx1 bacteriophages (57) in E. coli O157:H7, presumably via bacteriophage induction and excision. Ciprofloxacin lyses an stx1-negative/stx2+ E. coli O157:H7 strain, an effect attributed to induction of the stx2 bacteriophage (58). Antibiotics used as growth-promoting food supplements in agriculture induce Stx-encoding bacteriophages in several serotypes of STEC (30). We now demonstrate that TMP-SMX and fluoroquinolones, which increase stx2 expression in vitro (26, 27), promote the excision of stx2 bacteriophages as well as of complete and truncated stx1 bacteriophages. We additionally demonstrate that subinhibitory concentrations of fosfomycin, which increase the release of Stx from STEC (14, 55, 56), might, at least in some strains, lead to bacteriophage excision. Though fosfomycin is active against the bacterial cell wall, exposure to this compound results in induction and excision of the bacteriophage, raising the possibility that phage excision might be a nonspecific response of E. coli O157:H7 to bacterial stress. However, ampicillin, another cell wall-active antibiotic, produced no such effect. It is also interesting that the excision of bacteriophage does not necessarily result in rapid lysis of the bacterial cell, as evidenced by our ability to pellet bacteria in which the chromosome has intact insertion sites at yehV and wrbA. The isolation and study of viable E. coli O157:H7 in which excision has occurred will be instructive in determining the fate of the formerly integrated complete and truncated bacteriophages.

Recombination is the predominant mechanism of evolution of E. coli O157:H7. Its bacteriophages contain many recombination-prone regions (31), and the E. coli O157:H7 chromosome eliminates pseudogenes, presumably via recombination, faster than it acquires them (18). Antibiotics might also contribute to evolution as exogenous agents by inducing stx bacteriophages, leading to the deposition of bacteriophage DNA into the environmental genetic pool. Interestingly, chlorate and anaerobic growth lead to the duplication or deletion of the stx gene in S. dysenteriae serotype 1 (33).

The attenuation of bacteriophage excision by bile salts suggests that these ubiquitous intestinal compounds should be further investigated for their effects on bacteriophage stability and induction. Bile salts inhibit phage growth in Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis (22) and increase phage production in Bacteroides fragilis (1), but their effects on bacterial genomic stability and on virulence factor dissemination are largely unstudied. We should note that the analysis of bile salts and of antibiotics was confined only to pelleted, presumably nonlysed cells at the end of the incubation period. Also, we did not assess the effects of these agents on induction and lysis during the preceding 16 h of growth.

E. coli O157:H7 strains differ in their ability to produce Stx (9, 14), to adhere to (2, 41) and invade (49) eukaryotic cells, and to secrete proteins (34). Perhaps interstrain, and even interassay (48), phenotypic differences can be attributed, at least in part, to chromosomal instability. Indeed, it is interesting that STEC strains demonstrate differential rates of alteration of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis patterns during subculture (21). Furthermore, we wish to caution against assigning chromosomal insertion sites occupied or unoccupied statuses based solely on the generation from E. coli O157:H7 DNA of amplicons that are the sizes predicted from the K-12 chromosome sequence. Specifically, because a subset of chromosomal molecules from organisms grown overnight in broth culture sustained bacteriophage excisions, which would result in shorter amplicons, it is necessary to perform corroborative amplifications focusing on the junctions between the element of interest and the chromosome before proposing that an insertion site is not occupied in a particular strain. Also, categorizing an E. coli O157:H7 strain as stx1-negative/stx2+ without further characterization fails to address the diversity of chromosomal patterns that are present, and it might be inappropriate to draw epidemiologic conclusions or to associate genotypes of infecting isolates with clinical illnesses. This heterogeneity now warrants consideration when analyzing strains, as simple stx genotyping fails to address the diversity of chromosomal patterns within the E. coli O157:H7 serotype. Finally, these data demonstrate that pathogens chosen for sequencing, even those occurring within the same serotype, might not be representative of many members of that serotype.

In summary, the architecture of the E. coli O157:H7 chromosome is considerably more complex and diversified than previously recognized; its evolution involves either parallel acquisition of stx2 bacteriophages or, more likely, intrabacterial stx2 bacteriophage insertion site changes. Truncated bacteriophages occupy yehV in stx1-negative E. coli O157:H7. These truncated structures are either progenitors to or descendants of structures that contained stx1. Antibiotics promote excisions of complete and truncated bacteriophages. Bile salts, previously unrecognized modifiers of bacteriophage integration stability, can attenuate these excisions. Environmental factors in the diverse milieus in which STEC exists must be considered when the dynamism of the E. coli O157:H7 chromosome is examined.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Falkenhagen McKenzie for manuscript preparation, Srdjan Jelacic, Joseph Cagno, and Fritz Brown for primer suggestions, and Thomas Whittam for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by NIH grant AI47499.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araujo, R., M. Muniesa, J. Mendez, A. Puig, N. Queralt, F. Lucena, and J. Jofre. 2001. Optimisation and standardisation of a method for detecting and enumerating bacteriophages infecting Bacteroides fragilis. J. Virol. Methods 93:127-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashkenazi, S., M. Larocco, B. E. Murray, and T. G. Cleary. 1992. The adherence of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli to rabbit intestinal cells. J. Med. Microbiol. 37:304-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell, B. P., M. Goldoft, P. M. Griffin, M. A. Davis, D. C. Gordon, P. I. Tarr, C. A. Bartleson, J. H. Lewis, T. J. Barrett, and J. G. Wells. 1994. A multistate outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7-associated bloody diarrhea and hemolytic uremic syndrome from hamburgers. The Washington experience. JAMA 272:1349-1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilge, S. S., J. C. Vary, Jr., S. F. Dowell, and P. I. Tarr. 1996. Role of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 O side chain in adherence and analysis of an rfb locus. Infect. Immun. 64:4795-4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boerlin, P., S. A. McEwen, F. Boerlin-Petzold, J. B. Wilson, R. P. Johnson, and C. L. Gyles. 1999. Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:497-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bokete, T. N., T. S. Whittam, R. A. Wilson, C. R. Clausen, C. M. O'Callahan, S. L. Moseley, T. R. Fritsche, and P. I. Tarr. 1997. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Escherichia coli with enteropathogenic characteristics isolated from Seattle children. J. Infect. Dis. 175:1382-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, P. K., C. M. Dozois, C. A. Nickerson, A. Zuppardo, J. Terlonge, and R. Curtiss III. 2001. MlrA, a novel regulator of curli (AgF) and extracellular matrix synthesis by Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. Mol. Microbiol. 41:349-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calderwood, S. B., F. Auclair, A. Donohue-Rolfe, G. T. Keusch, and J. J. Mekalanos. 1987. Nucleotide sequence of the Shiga-like toxin genes of Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:4364-4368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cornick, N. A., S. Jelacic, M. A. Ciol, and P. I. Tarr. 2002. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections: discordance between filterable fecal Shiga toxin and disease outcome. J. Infect. Dis. 186:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coste, G., and F. Bernardi. 1987. Cloning and characterization of the immunity region of phage phi 80. Mol. Gen. Genet. 206:452-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng, P., K. A. Lampel, H. Karch, and T. S. Whittam. 1998. Genotypic and phenotypic changes in the emergence of Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Infect. Dis. 177:1750-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gish, W., and D. J. States. 1993. Identification of protein coding regions by database similarity search. Nat. Genet. 3:266-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grandori, R., P. Khalifah, J. A. Boice, R. Fairman, K. Giovanielli, and J. Carey. 1998. Biochemical characterization of WrbA, founding member of a new family of multimeric flavodoxin-like proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 273:20960-20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grif, K., M. P. Dierich, H. Karch, and F. Allerberger. 1998. Strain-specific differences in the amount of Shiga toxin released from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 following exposure to subinhibitory concentrations of antimicrobial agents. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 17:761-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunzer, F., H. Bohm, H. Russmann, M. Bitzan, S. Aleksic, and H. Karch. 1992. Molecular detection of sorbitol-fermenting Escherichia coli O157 in patients with hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:1807-1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi, T., K. Makino, M. Ohnishi, K. Kurokawa, K. Ishii, K. Yokoyama, C. G. Han, E. Ohtsubo, K. Nakayama, T. Murata, M. Tanaka, T. Tobe, T. Iida, H. Takami, T. Honda, C. Sasakawa, N. Ogasawara, T. Yasunaga, S. Kuhara, T. Shiba, M. Hattori, and H. Shinagawa. 2001. Complete genome sequence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genomic comparison with a laboratory strain K-12. DNA Res. 8:11-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hendrix, R. W., M. C. Smith, R. N. Burns, M. E. Ford, and G. F. Hatfull. 1999. Evolutionary relationships among diverse bacteriophages and prophages: all the world's a phage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:2192-2197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Homma, K., S. Fukuchi, T. Kawabata, M. Ota, and K. Nishikawa. 2002. A systematic investigation identifies a significant number of probable pseudogenes in the Escherichia coli genome. Gene 294:25-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang, A., J. Friesen, and J. L. Brunton. 1987. Characterization of a bacteriophage that carries the genes for production of Shiga-like toxin 1 in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 169:4308-4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hull, A. E., D. W. Acheson, P. Echeverria, A. Donohue-Rolfe, and G. T. Keusch. 1993. Mitomycin immunoblot colony assay for detection of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli in fecal samples: comparison with DNA probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1167-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iguchi, A., R. Osawa, J. Kawano, A. Shimizu, J. Terajima, and H. Watanabe. 2002. Effects of repeated subculturing and prolonged storage at room temperature of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 on pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profiles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3079-3081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jamasbi, R. J., and L. J. Paulissen. 1978. Influence of bacteriological media constituents on the reproduction of Salmonella enteritidis bacteriophages. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 44:49-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jelacic, S., C. L. Wobbe, D. R. Boster, M. A. Ciol, S. L. Watkins, P. I. Tarr, and A. E. Stapleton. 2002. ABO and P1 blood group antigen expression and stx genotype and outcome of childhood Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. J. Infect. Dis. 185:214-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahan, F. M., J. S. Kahan, P. J. Cassidy, and H. Kropp. 1974. The mechanism of action of fosfomycin (phosphonomycin). Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 235:364-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karch, H., H. Bohm, H. Schmidt, F. Gunzer, S. Aleksic, and J. Heesemann. 1993. Clonal structure and pathogenicity of Shiga-like toxin-producing, sorbitol-fermenting Escherichia coli O157:H−. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:1200-1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimmitt, P. T., C. R. Harwood, and M. R. Barer. 1999. Induction of type 2 Shiga toxin synthesis in Escherichia coli O157 by 4-quinolones. Lancet 353:1588-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimmitt, P. T., C. R. Harwood, and M. R. Barer. 2000. Toxin gene expression by shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: the role of antibiotics and the bacterial SOS response. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 6:458-465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein, E. J., J. R. Stapp, C. R. Clausen, D. R. Boster, S. Jelacic, J. G. Wells, X. Qin, D. L. Swerdlow, and P. I. Tarr. 2002. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in children with diarrhea: a prospective point of care study. J. Pediatr. 141:172-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koch, C., S. Hertwig, R. Lurz, B. Appel, and L. Beutin. 2001. Isolation of a lysogenic bacteriophage carrying the stx1OX gene, which is closely associated with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from sheep and humans. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3992-3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohler, B., H. Karch, and H. Schmidt. 2000. Antibacterials that are used as growth promoters in animal husbandry can affect the release of Shiga-toxin-2-converting bacteriophages and Shiga toxin 2 from Escherichia coli strains. Microbiology 146:1085-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kudva, I. T., P. S. Evans, N. T. Perna, T. J. Barrett, F. M. Ausubel, F. R. Blattner, and S. B. Calderwood. 2002. Strains of Escherichia coli O157:H7 differ primarily by insertions or deletions, not single-nucleotide polymorphisms. J. Bacteriol. 184:1873-1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Makino, K., K. Yokoyama, Y. Kubota, C. H. Yutsudo, S. Kimura, K. Kurokawa, K. Ishii, M. Hattori, I. Tatsuno, H. Abe, T. Iida, K. Yamamoto, M. Onishi, T. Hayashi, T. Yasunaga, T. Honda, C. Sasakawa, and H. Shinagawa. 1999. Complete nucleotide sequence of the prophage VT2-Sakai carrying the verotoxin 2 genes of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 derived from the Sakai outbreak. Genes Genet. Syst. 74:227-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonough, M. A., and J. R. Butterton. 1999. Spontaneous tandem amplification and deletion of the Shiga toxin operon in Shigella dysenteriae 1. Mol. Microbiol. 34:1058-1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McNally, A., A. J. Roe, S. Simpson, F. M. Thomson-Carter, D. E. Hoey, C. Currie, T. Chakraborty, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2001. Differences in levels of secreted locus of enterocyte effacement proteins between human disease-associated and bovine Escherichia coli O157. Infect. Immun. 69:5107-5114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 35.Milliken, G. A., and D. E. Johnson. 1992. Analysis of messy data, vol. 1. Designed experiments. Chapman and Hall, London, England.

- 36.Newland, J. W., N. A. Strockbine, and R. J. Neill. 1987. Cloning of genes for production of Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin type II. Infect. Immun. 55:2675-2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohnishi, M., J. Terajima, K. Kurokawa, K. Nakayama, T. Murata, K. Tamura, Y. Ogura, H. Watanabe, and T. Hayashi. 2002. Genomic diversity of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157 revealed by whole genome PCR scanning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:17043-17048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostroff, S. M., P. I. Tarr, M. A. Neill, J. H. Lewis, N. Hargrett-Bean, and J. M. Kobayashi. 1989. Toxin genotypes and plasmid profiles as determinants of systemic sequelae in Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. J. Infect. Dis. 160:994-998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perna, N. T., G. Plunkett III, V. Burland, B. Mau, J. D. Glasner, D. J. Rose, G. F. Mayhew, P. S. Evans, J. Gregor, H. A. Kirkpatrick, G. Posfai, J. Hackett, S. Klink, A. Boutin, Y. Shao, L. Miller, E. J. Grotbeck, N. W. Davis, A. Lim, E. T. Dimalanta, K. D. Potamousis, J. Apodaca, T. S. Anantharaman, J. Lin, G. Yen, D. C. Schwartz, R. A. Welch, and F. R. Blattner. 2001. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 409:529-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plunkett, G., III, D. J. Rose, T. J. Durfee, and F. R. Blattner. 1999. Sequence of Shiga toxin 2 phage 933W from Escherichia coli O157:H7: Shiga toxin as a phage late-gene product. J. Bacteriol. 181:1767-1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ratnam, S., S. B. March, R. Ahmed, G. S. Bezanson, and S. Kasatiya. 1988. Characterization of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. J. Clin. Microbiol. 26:2006-2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Recktenwald, J., and H. Schmidt. 2002. The nucleotide sequence of Shiga toxin (Stx) 2e-encoding phage φP27 is not related to other Stx phage genomes, but the modular genetic structure is conserved. Infect. Immun. 70:1896-1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 44.Tarr, P. I., S. S. Bilge, J. C. Vary, Jr., S. Jelacic, R. L. Habeeb, T. R. Ward, M. R. Baylor, and T. E. Besser. 2000. Iha: a novel Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence-conferring molecule encoded on a recently acquired chromosomal island of conserved structure. Infect. Immun. 68:1400-1407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tarr, P. I., M. A. Neill, C. R. Clausen, J. W. Newland, R. J. Neill, and S. L. Moseley. 1989. Genotypic variation in pathogenic Escherichia coli O157:H7 isolated from patients in Washington, 1984-1987. J. Infect. Dis. 159:344-347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarr, P. I., L. M. Schoening, Y. L. Yea, T. R. Ward, S. Jelacic, and T. S. Whittam. 2000. Acquisition of the rfb-gnd cluster in evolution of Escherichia coli O55 and O157. J. Bacteriol. 182:6183-6191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Teel, L. D., A. R. Melton-Celsa, C. K. Schmitt, and A. D. O'Brien. 2002. One of two copies of the gene for the activatable Shiga toxin type 2d in Escherichia coli O91:H21 strain B2F1 is associated with an inducible bacteriophage. Infect. Immun. 70:4282-4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toth, I., M. L. Cohen, H. S. Rumschlag, L. W. Riley, E. H. White, J. H. Carr, W. W. Bond, and I. K. Wachsmuth. 1990. Influence of the 60-megadalton plasmid on adherence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and genetic derivatives. Infect. Immun. 58:1223-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uhlich, G. A., J. E. Keen, and R. O. Elder. 2002. Variations in the csgD promoter of Escherichia coli O157:H7 associated with increased virulence in mice and increased invasion of HEp-2 cells. Infect. Immun. 70:395-399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang, L., S. Huskic, A. Cisterne, D. Rothemund, and P. R. Reeves. 2002. The O-antigen gene cluster of Escherichia coli O55:H7 and identification of a new UDP-GlcNAc C4 epimerase gene. J. Bacteriol. 184:2620-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Welinder-Olsson, C., M. Badenfors, T. Cheasty, E. Kjellin, and B. Kaijser. 2002. Genetic profiling of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains in relation to clonality and clinical signs of infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:959-964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whittam, T. S. 1998. Evolution of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains, p. 195-209. In A. D. O'Brien (ed.), Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains. ASM Press, Washington, D.C.

- 53.Whittam, T. S. 1995. Genetic population structure and pathogenicity in enteric bacteria. Symp. Soc. Gen. Microbiol. 52:214-245. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Whittam, T. S., M. L. Wolfe, I. K. Wachsmuth, F. Orskov, I. Orskov, and R. A. Wilson. 1993. Clonal relationships among Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis and infantile diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 61:1619-1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yoh, M., E. K. Frimpong, and T. Honda. 1997. Effect of antimicrobial agents, especially fosfomycin, on the production and release of Vero toxin by enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 19:57-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yoh, M., and T. Honda. 1997. The stimulating effect of fosfomycin, an antibiotic in common use in Japan, on the production/release of verotoxin-1 from enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 in vitro. Epidemiol. Infect. 119:101-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yokoyama, K., K. Makino, Y. Kubota, M. Watanabe, S. Kimura, C. H. Yutsudo, K. Kurokawa, K. Ishii, M. Hattori, I. Tatsuno, H. Abe, M. Yoh, T. Iida, M. Ohnishi, T. Hayashi, T. Yasunaga, T. Honda, C. Sasakawa, and H. Shinagawa. 2000. Complete nucleotide sequence of the prophage VT1-Sakai carrying the Shiga toxin 1 genes of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain derived from the Sakai outbreak. Gene 258:127-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang, X., A. D. McDaniel, L. E. Wolf, G. T. Keusch, M. K. Waldor, and D. W. Acheson. 2000. Quinolone antibiotics induce Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages, toxin production, and death in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 181:664-670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]