Abstract

We have isolated a new protein from the nacreous layer of the shell of the sea snail Haliotis laevigata (abalone). Amino acid sequence analysis showed the protein to consist of 134 amino acids and to contain three sequence repeats of ∼40 amino acids which were very similar to the well-known whey acidic protein domains of other proteins. The new protein was therefore named perlwapin. In addition to the major sequence, we identified several minor variants. Atomic force microscopy was used to explore the interaction of perlwapin with calcite crystals. Monomolecular layers of calcite crystals dissolve very slowly in deionized water and recrystallize in supersaturated calcium carbonate solution. When perlwapin was dissolved in the supersaturated calcium carbonate solution, growth of the crystal was inhibited immediately. Perlwapin molecules bound tightly to distinct step edges, preventing the crystal layers from growing. Using lower concentrations of perlwapin in a saturated calcium carbonate solution, we could distinguish native, active perlwapin molecules from denaturated ones. These observations showed that perlwapin can act as a growth inhibitor for calcium carbonate crystals in saturated calcium carbonate solution. The function of perlwapin in nacre growth may be to inhibit the growth of certain crystallographic planes in the mineral phase of the polymer/mineral composite nacre.

INTRODUCTION

Molluskan nacre is a biocomposite consisting to ∼95% of the aragonitic polymorph of calcium carbonate and an organic matrix of polysaccharide and protein (1–4). Nacre has a fracture toughness three orders of magnitude higher than the pure mineral, a tensile strength of 140–170 MPa, and a Young's modulus of 60–70 GPa. These extraordinary physical properties are due to the structure and composition of the biocomposite. The mineral phase of abalone nacre consists of vertical stacks of flat polygonal aragonite tablets which form brick-wall-like horizontal sheets of lamellae. Each tablet is encased by an organic matrix which leaves pores for mineral bridges connecting the tablets of a stack to form a single crystal (5,6). The organic matrix thus guides crystal growth to form the characteristic brick and mortar construction of nacre and acts as an adhesive, filling the space between aragonite crystals as shown by atomic force microscopy (AFM) (7).

A major component of the insoluble fraction of the matrix is the polysaccharide chitin (8,9), which may act as a scaffold in the interlamellar organic sheets. The first protein from abalone nacre characterized by sequence analysis was the large multidomain protein lustrin A (10), which has been shown to be a component of the adhesive between aragonite tablets (7). Recently two other proteins, perlucin and perlustrin, were isolated from nacre and characterized at the molecular level (11). Perlucin is a C-type lectin with galactose/mannose binding specificity (12) which nucleates new layers in a calcium carbonate crystal when added to calcite crystals and precipitates together with calcium carbonate crystals in in vitro assays (13). Perlustrin is an insulin- and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein (14), the presence of which in nacre may be related to earlier findings (15) that extracts of nacre stimulate proliferation and differentiation processes of vertebrate fibroblasts, bone-marrow cells, and osteoblasts.

The AFM (16) is a valuable tool to investigate dynamic processes on mineral surfaces and protein-mineral interactions on the micro- and nanometer scale. The time frame of AFM imaging is compatible with the speed of growth and dissolution of molecular layers of calcite crystals, and therefore this method can be used to study the effect of different solvents on surface layers of the calcium carbonate polymorph calcite (17). It was also possible to observe the interaction of a mixture of water-soluble nacre proteins with calcite, and it was shown that binding of such proteins can change the shape of atomic step edges on the calcite crystal surface and the speed of crystal growth (18). The protein mixture also induced the transition from calcite to aragonite when applied to a growing calcite surface (19). In this report, we describe the isolation and sequence analysis of perlwapin, an abalone nacre protein consisting of three consecutive WAP domains, and the effect of the purified protein on calcium carbonate crystallization as shown by AFM in aqueous solution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Protein isolation and amino acid sequence analysis

The matrix proteins of Haliotis laevigata nacre were isolated as described (11). Perlwapin was identified as a new protein by screening the peaks obtained after reversed phase high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis using Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) sequencer models 473A and 492. The purified protein was reduced and pyridylethylated as before (20). Reagents were removed, and the protein was further purified when necessary, after acidification of the sample with trifluoroacetic acid to pH ∼ 1, using a small C4 reversed phase column (11). Enzymatic cleavages were done at an enzyme/substrate ratio of ∼1:100. The enzymes used were Achromobacter lysyl endopeptidase (WAKO Chemicals, Neuss, Germany) in 0.1 M ammonium hydrogen carbonate containing 3.5 M urea for 15 h at 23°C, or thermolysin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) in the same buffer for 8 h at 30°C. The resulting fragments were separated according to size using a Superdex Peptide column (HR10/30, Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany) in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid containing 25% acetonitrile at a flow rate of 0.3 ml/min. Peptides of similar size were further separated by reversed phase HPLC using a PerfectSil C18 column (250 × 3 mm; MZ-Analysentechnik, Mainz, Germany) with a gradient of 10–60% solvent B (solvent A, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid; solvent B, 70% acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) in 160 min at a flow rate of 0.25 ml/min.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in 10–15% gels followed established protocols. Amino acid analysis was performed on a Biotronik LC3000 (Biotronik, Maintal, Germany) after hydrolysis of the protein in 6 N HCl for 24 h at 110°C. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry was done on a Q-Tof Ultima instrument (Micromass, Manchester, UK) using the software packages supplied by the manufacturer for data evaluation.

AFM IMAGING

Preparation of saturated calcium carbonate solution

Saturated CaCO3 solution was prepared according to Hillner et al. (17). A solution of 100 mM NaHCO3 was added slowly to 1000 ml of 40 mM CaCl2 with continuous stirring until the solution became turbid. The final pH was adjusted to 8.2 with 10 N NaOH. The solution was filtered sterile through a filter with pores of 0.22 μm and stored in glass bottles at 4°C.

Dialysis against saturated calcium carbonate solution

Perlwapin solution (in citrate buffer, pH 4.8) was concentrated in a speed vac concentrator (Savant Speed Vac, Schütt Labortechnik, Göttingen, Germany) and then dialyzed against three changes of saturated CaCO3 solution in a dialysis tube with a molecular weight cutoff of 6000–8000 (Spectra/Por, Karl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany), which was boiled in EDTA for 15 min and rinsed several times with deionized water before use. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bradford essay with bovine serum albumin and IgG as standard proteins (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Munich, Germany). The perlwapin solution was stored at 4°C.

Calcite preparation

Freshly cleaved calcite surfaces for AFM investigations ( plane) were cut from a block of geological calcite of optical quality (Creel, Mexico; Kristalldruse, Munich, Germany) using a razor blade. The calcite crystals were handled with tweezers to avoid contamination of the surface and examined with an optical microscope. Fragments which presented a flat surface were glued with a two-component epoxy glue (Bindulin-Werk, H. L. Schönleber, Fürth, Germany) on clean mica plates previously glued onto a magnetic steel disk (12-mm diameter). The dry calcite sample was then carefully rinsed with deionized water to remove calcite dust particles from the cleavage site before it was positioned at the top of the scanner.

plane) were cut from a block of geological calcite of optical quality (Creel, Mexico; Kristalldruse, Munich, Germany) using a razor blade. The calcite crystals were handled with tweezers to avoid contamination of the surface and examined with an optical microscope. Fragments which presented a flat surface were glued with a two-component epoxy glue (Bindulin-Werk, H. L. Schönleber, Fürth, Germany) on clean mica plates previously glued onto a magnetic steel disk (12-mm diameter). The dry calcite sample was then carefully rinsed with deionized water to remove calcite dust particles from the cleavage site before it was positioned at the top of the scanner.

Interaction of perlwapin with calcite surface

AFM imaging was performed with a commercial system (Nanoscope IIIa Multimode; Digital Instruments, Santa Barbara, CA) equipped with a piezoelectric scanner (“E” scanner with a maximum scan rage of 10 × 10 × 4 μm) and silicon nitride (Si3N4) cantilevers (Microlevers, Park Scientific Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA) with oxide-sharpened tips. They were treated with UV light for 10 min before use to destroy organic contaminants on the tip surface. The glass fluid cell and the silicon O-ring were cleaned with a specific detergent (Ultra Joy, Procter & Gamble), rinsed with water, and dried with a flow of compressed nitrogen.

The fluid cell was filled with deionized water (at room temperature) using a 1-ml dosage syringe (Injekt-F 1 ml, Braun, Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany). A suitable surface of 10 μm × 10 μm was imaged in contact mode (tip with force constant of 0.03 N/m) for several minutes. A scan rate of 4 Hz and 512 sample/line were chosen, and imaging force was varied during the experiment to optimize image quality. The surface showed steps of a height of ∼0.25 nm. Several defects of rhombohedral shape were present. To investigate the interaction between perlwapin and calcite, saturated calcium carbonate solution containing perlwapin (0.002 mg/ml or 0.02 mg/ml as indicated in the Results section) was carefully added to the fluid cell using a 1-ml syringe until the aqueous solution in the fluid cell was completely exchanged. The exchange of the buffer solution caused a drift of the sample, but part of the area initially imaged was still observable.

RESULTS

Sequence analysis of perlwapin

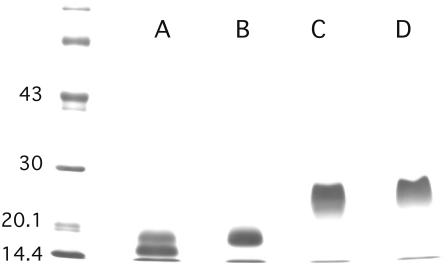

Perlwapin was identified as a new nacre matrix protein by N-terminal sequence analysis of proteins isolated by a combination of ion-exchange and reversed phase chromatography. In SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, perlwapin appeared as a broad band with a relative mobility corresponding to ∼25 kDa (Fig. 1). Upon reduction the Mr decreased to ∼18 kDa. The N-terminus of perlwapin samples was not homogeneous but also contained shorter molecules starting at Gly-2 and Leu-5 of the major sequence (Fig. 2). Almost all preparations also contained variable amounts of an additional sequence, DAGVC, which was later shown to be due to internal cleavage between Tyr-99 and Asp-100 (Fig. 2). These cleavages probably occurred during purification and were caused by unknown proteases residing in the nacre organic matrix. Preparations with a high proportion of cleaved molecules showed no substantial decrease of relative mobility in SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, indicating that the two fragments were disulfide-bonded (Fig. 1). However, under reducing conditions the Mr of the major band in such samples decreased to ∼15 kDa due to the loss of a C-terminal fragment of 35 amino acids.

FIGURE 1.

PAGE of perlwapin. SDS-PAGE was done using 10–15% acrylamide gels which were stained with Coomassie blue. (Lanes A and B) Sample buffer containing mercaptoethanol as reducing agent; (lanes C and D) sample buffer without reducing agent. The sample run in lanes A and C contained 60–70% perlwapin molecules cleaved at the Tyr-99-Asp-100 bond, as estimated from sequence analysis. The sample run in lanes B and D showed no cleavage. The N-terminal and C-terminal fragments were held together by disulfide bonds in the cleaved sample if run under nonreducing conditions (lane D). The difference of ∼3000 Da between the major bands under reducing conditions (lanes A and B) is in good agreement with the loss of 35 amino acids in cleaved perlwapin (lane A). The position of molecular mass markers is indicated in kDa on the left.

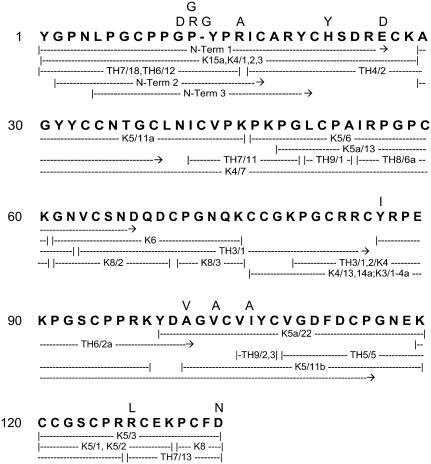

FIGURE 2.

The amino acid sequence of perlwapin. The major sequence is in bold; variations are shown on top of the major sequence. K, peptides obtained by cleavage with lysyl endopeptidase; TH, peptides from cleavage with thermolysin. Numbers denote chromatographic pools. K–P bonds were cleaved only partially by lysyl endopeptidase. Some unspecific cleavages were observed.

For sequence analysis the disulfide bonds were reduced and the cysteines pyridylethylated under denaturing conditions. The pyridylethylated protein was cleaved with lysyl endopeptidase and thermolysin, and the resulting fragments were purified by combining size-exclusion chromatography with reversed phase HPLC and sequenced. Overlapping sequences were aligned to yield the complete sequence of the protein (Fig. 2). In addition to the endogenous proteolytic cleavages, we observed the occurrence of more than one amino acid at many positions (Fig. 2). A sequence region with particularly high variability was found between Pro-10 and Ile-16 of the major sequence. The sequence variants differing from the major sequence and found in different peptides were 10PGRYPR, 10PGGYPR, 10PDPYPR, 10PDRYPR, and 10PDRGYPA. The latter sequence variant even contained an insertion (underlined). Possibly this list is not complete because other sequence variants may have remained unnoticed, for instance, because they occurred in too low concentrations or because the respective peptides were not pure enough to allow unequivocal identification. We do not know whether this heterogeneity is due to multiple genes in single organisms or subspecies variations, or both. Another region of high sequence variability was from Asp-100 to Tyr-107 where the second most frequent amino acid sequence was 100DVGACVI. The major sequence (shown in bold in Fig. 2) consisted of 134 amino acids. The calculated molecular mass, presuming disulfide bonds between cysteines, was 14519.9 Da. As expected from the many sequence variations and N-terminal cleavages, electrospray ionization mass spectrometric measurements showed a broad signal ranging from ∼14,400 to 15,000 Da (not shown).

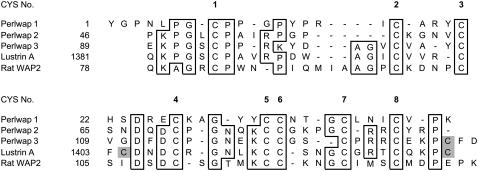

Careful inspection of the sequence showed that it consisted of three consecutive repeats with ∼42 amino acids and a characteristic cysteine pattern (Fig. 3); 40–53% of the amino acids were identical between the repeats (Table 1). Database searches using the FASTA program (at EBI, Hinxton, UK; http://www.ebi.ac.uk) showed that all three repeats were very similar to WAP domains of many proteins with sequence identities from 30% to 50% for the best matches. Therefore the protein was named perlwapin. A particularly high percentage of identical amino acids (61.4%, Table 1) was found between repeat 3 of perlwapin and the WAP domain of the Haliotis rufescens nacre protein lustrin A (10). This third perlwapin repeat contained an additional, ninth, cysteine which was not present in the other repeats but coincided with one of the two additional cysteines found in the lustrin A WAP domain (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Alignment of perlwapin WAP domain sequences to each other and to selected WAP domain sequences of other proteins. The lustrin A sequence (10) is from another Haliotis species, the rat sequence is from domain 2 of rat milk WAP (29), which was chosen arbitrarily as a representative vertebrate WAP domain. The cysteines forming the regular motif of WAP domains are numbered above the alignment; extra cysteines (one in perlwapin domain 3 and two in lustrin A) are shaded.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of perlwapin WAP domains to each other and to selected WAP domains of other proteins

| Perl 1 | Perl 2 | Perl 3 | Lus A | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perl 2 | 40.5 | |||

| Perl 3 | 42.9 | 53.5 | ||

| Lus A | 42.9 | 53.5 | 61.4 | |

| Rat | 35.7 | 48.8 | 40.9 | 47.8 |

Perl 1–3, the WAP domains 1, 2, and 3 of perlwapin; Lus A, the WAP domain of lustrin A; Rat, WAP domain 2 of rat WAP. The percentage of identical amino acids was calculated according to the alignment of sequences in Fig. 3.

Protein/mineral interaction observed by atomic force microscopy

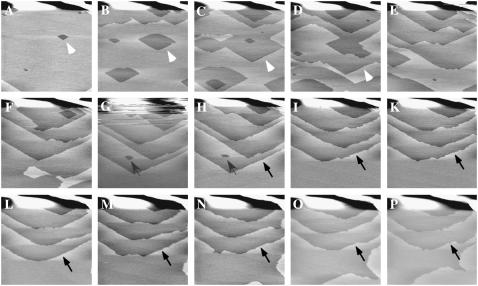

The atomic force microscope was used to directly observe the interaction of perlwapin with the mineral calcite. It has been shown that growth and dissolution of geological calcite can be imaged in real time by AFM. In Fig. 4 a flat ( ) calcite surface is shown which started to dissociate after incubation with deionized water at defects in the upper layer (white arrows). From there, layers of molecular thickness dissolved starting at the edges (Fig. 4, A–F) and uncovered the subjacent layers. In the uncovered layers the dissociation of the crystal surface started again at the defects, leading to slow dissolution of the crystal. The streaks at the top of Fig. 4 G were caused by the injection of saturated calcium carbonate solution into the fluid cell. The crystal started immediately to grow. First the defects healed out (Fig. 4, G–I, gray arrows), then the edges of the steps grew (Fig. 4, H–P, black arrow) until the layers became confluent. Thus, the crystal surface became smoother with increasing incubation time in saturated calcium carbonate solution.

) calcite surface is shown which started to dissociate after incubation with deionized water at defects in the upper layer (white arrows). From there, layers of molecular thickness dissolved starting at the edges (Fig. 4, A–F) and uncovered the subjacent layers. In the uncovered layers the dissociation of the crystal surface started again at the defects, leading to slow dissolution of the crystal. The streaks at the top of Fig. 4 G were caused by the injection of saturated calcium carbonate solution into the fluid cell. The crystal started immediately to grow. First the defects healed out (Fig. 4, G–I, gray arrows), then the edges of the steps grew (Fig. 4, H–P, black arrow) until the layers became confluent. Thus, the crystal surface became smoother with increasing incubation time in saturated calcium carbonate solution.

FIGURE 4.

AFM images of the surface of a calcite crystal in aqueous solution. A–E, subsequent images of the dissolution of a calcite surface (cleaved along the ( ) plane) in deionized water at room temperature. An etching of monomolecular layers was observed (white arrows) from one image to the next. G–P, the aqueous solution in the fluid cell was changed against saturated calcium carbonate solution in G; subsequent images show the growth of the calcite surface in saturated calcium car bonate solution. The streaks at the top of G are due to the injection of the saturated calcium carbonate solution. Note the growth of the crystal layers at the defects (gray arrows) and etches (black arrows). All images presented were taken in contact mode with a scan rate of 4 Hz and 512 pixels per line. Cantilevers with a force constant of 0.03 N/m were used. Frames A and N are 30 min apart.

) plane) in deionized water at room temperature. An etching of monomolecular layers was observed (white arrows) from one image to the next. G–P, the aqueous solution in the fluid cell was changed against saturated calcium carbonate solution in G; subsequent images show the growth of the calcite surface in saturated calcium car bonate solution. The streaks at the top of G are due to the injection of the saturated calcium carbonate solution. Note the growth of the crystal layers at the defects (gray arrows) and etches (black arrows). All images presented were taken in contact mode with a scan rate of 4 Hz and 512 pixels per line. Cantilevers with a force constant of 0.03 N/m were used. Frames A and N are 30 min apart.

Perlwapin incubated with calcite in saturated calcium carbonate solution

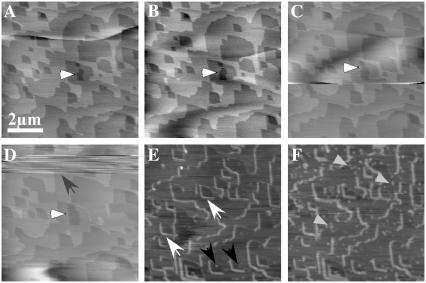

The surface of a small calcite crystal was used to investigate the interaction of the protein perlwapin with the calcium carbonate mineral by AFM. In Fig. 5 the surface of a small piece of calcite in aqueous solution is shown. Orthorhombic defects in the surface layers were visible which grew when deionized water was added (Fig. 5, A–D, white arrows). During scanning the upper half of image D (Fig. 5) downward, the solution was exchanged against saturated calcium carbonate solution containing 0.02 mg/ml of perlwapin. The streaks in the image during flushing in of the new solution were due to a lift off of the tip caused by turbulences. The solution took some time to diffuse underneath the scanning tip. In the subsequent image (Fig. 5 E) the step edges were already covered by perlwapin molecules, which bound with high affinity. By binding to the edges the protein inhibited the growth of the calcite crystal (Fig. 5 F). Some single perlwapin molecules were also attached to the top of the calcite layers (Fig. 5 F, gray arrows).

FIGURE 5.

AFM images of the surface of a calcite crystal in aqueous solution. A–C show spontaneous dissolution of the calcite surface (cleavage along the ( ) plane) in deionized water at room temperature. The expected spontaneous etching phenomenon and consequent dissolution of atomic layers is observed. (D) Aqueous solution in the fluid cell was completely replaced by saturated calcium carbonate solution containing perlwapin (0.02 mg/ml). A small drift in the sample is visible. (E and F) Images showing the interaction of perlwapin with the calcite surface. Perlwapin adheres specifically to calcite steps (white arrows) enhancing the height of the edges and inhibiting the growth of new calcite layers. Perlwapin also adheres to crystal defects (black arrows). All images presented were taken in contact mode with a scan rate of 4 Hz and 512 pixels per line. Cantilevers with a force constant of 0.03 N/m were used. Frames A and F are 30 min apart.

) plane) in deionized water at room temperature. The expected spontaneous etching phenomenon and consequent dissolution of atomic layers is observed. (D) Aqueous solution in the fluid cell was completely replaced by saturated calcium carbonate solution containing perlwapin (0.02 mg/ml). A small drift in the sample is visible. (E and F) Images showing the interaction of perlwapin with the calcite surface. Perlwapin adheres specifically to calcite steps (white arrows) enhancing the height of the edges and inhibiting the growth of new calcite layers. Perlwapin also adheres to crystal defects (black arrows). All images presented were taken in contact mode with a scan rate of 4 Hz and 512 pixels per line. Cantilevers with a force constant of 0.03 N/m were used. Frames A and F are 30 min apart.

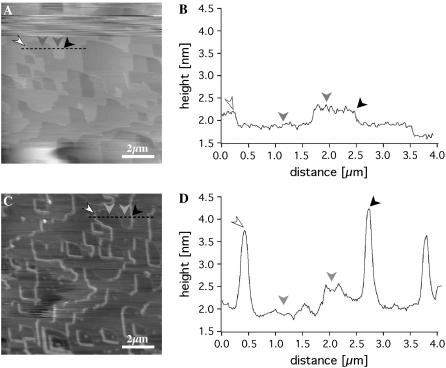

By measuring the height of the ridges we estimated the dimensions of the perlwapin molecule (Fig. 6). In Fig. 6 A a line plot is shown covering several steps on the crystal surface. The height of a monomolecular layer in the calcite crystal was ∼0.35 nm (Fig. 6, A and B, height difference between gray arrows), which was in good agreement with literature data (17). After incubation in a solution of 0.02 mg/ml perlwapin in saturated calcium carbonate, the step edges were decorated with ridges of a height of ∼2 nm (Fig. 6, C and D, difference between gray and black arrows). This indicated that the protein perlwapin bound to step edges of calcite at the ( ) plane such that a further growth of the crystal was prevented. The height of the structures and the appearance in AFM measurements suggested perlwapin to be a globular protein with a diameter of 2 nm. Due to the finite size of the AFM tip, there was a tip broadening of the displayed structures in dependence of the geometry of the imaging tip (21) when it was assumed that all molecules were bound in the same orientation.

) plane such that a further growth of the crystal was prevented. The height of the structures and the appearance in AFM measurements suggested perlwapin to be a globular protein with a diameter of 2 nm. Due to the finite size of the AFM tip, there was a tip broadening of the displayed structures in dependence of the geometry of the imaging tip (21) when it was assumed that all molecules were bound in the same orientation.

FIGURE 6.

AFM images and line profiles of a geological calcite surface before and after incubation of perlwapin. (A) AFM image of a calcite surface in aqueous solution at room temperature, before addition of a saturated calcium carbonate solution and corresponding profile (B). The surface is characterized by typical rhombohedral geometry, a unique characteristic of calcite. The averaged step height was calculated as 0.25 nm (gray arrows). (C) AFM image of calcite surface incubated with a calcium carbonate solution containing perlwapin (0.02 mg/ml) and corresponding profile (D). Perlwapin binds specifically to calcite steps and inhibits the growth of calcite layers. The diameter of the protein is ∼2 nm (white arrows and black arrows). Compare with the step height of 0.25 nm of a monomolecular calcite step (gray arrows). Note the drift of the sample (due to the flushing in of the protein solution).

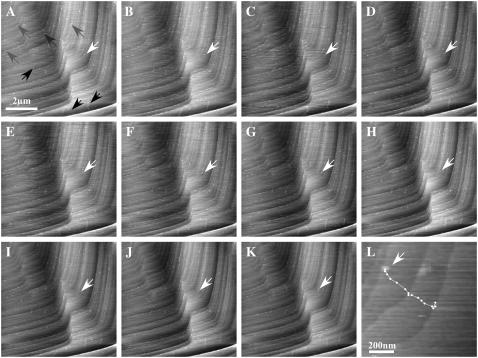

Using a lower concentration of perlwapin in our AFM experiments, we were able to detect single protein molecules and to investigate differences in the behavior of the protein molecules. The imaging process was started when the whole setup was in equilibrium again after flushing with the protein solution (Fig. 7 A). In Fig. 7, A–K, consecutive AFM images of the ( ) plane of a calcite crystal are shown. In Fig. 7 A some proteins were already tightly bound to a step edge (gray arrows). Some proteins formed clusters because they were piled up by the movement of the scanning tip (black arrows) and some single molecules were so loosely bound that they slowly moved (white arrow) across the surface. Those molecules which were tightly bound (gray arrows) to the step edges reached their destination so fast that the imaging process had not been started yet to detect their trajectories. We assume that these molecules were native and active. The clustering protein molecules were probably denatured and could not bind to the mineral crystal any more. Some proteins diffused randomly over the surface (one example is indicated by the white arrow) before they reached a suitable binding site at a step edge after several tens of minutes (see white arrows in Fig. 7, C–K, and trace in Fig. 7 L).

) plane of a calcite crystal are shown. In Fig. 7 A some proteins were already tightly bound to a step edge (gray arrows). Some proteins formed clusters because they were piled up by the movement of the scanning tip (black arrows) and some single molecules were so loosely bound that they slowly moved (white arrow) across the surface. Those molecules which were tightly bound (gray arrows) to the step edges reached their destination so fast that the imaging process had not been started yet to detect their trajectories. We assume that these molecules were native and active. The clustering protein molecules were probably denatured and could not bind to the mineral crystal any more. Some proteins diffused randomly over the surface (one example is indicated by the white arrow) before they reached a suitable binding site at a step edge after several tens of minutes (see white arrows in Fig. 7, C–K, and trace in Fig. 7 L).

FIGURE 7.

AFM images showing the interaction of single perlwapin molecules with a geologically grown calcite surface. (A–L) Calcite, cleaved along the ( ) plane, was incubated in a saturated calcium carbonate solution containing perlwapin (0.002 mg/ml). Single perlwapin molecules bind to calcite steps. Some molecules seemed to be denaturated (black arrows). They were aggregated and loosely attached to the calcite surface. The AFM tip pushed them over the surface while scanning. Other proteins were strongly bound to crystal steps as single molecules (gray arrows). Some of the proteins slowly moved over the surface before they bound to a calcite step (white arrows). In the close-up view (rectangle in K) the trace of the protein (white arrows A–K) is shown. All images presented were taken in contact mode at a scan rate of 4 Hz and 512 pixels per line. Cantilevers with a force constant of 0.03 N/m were used. Frames A and K were 50 min apart.

) plane, was incubated in a saturated calcium carbonate solution containing perlwapin (0.002 mg/ml). Single perlwapin molecules bind to calcite steps. Some molecules seemed to be denaturated (black arrows). They were aggregated and loosely attached to the calcite surface. The AFM tip pushed them over the surface while scanning. Other proteins were strongly bound to crystal steps as single molecules (gray arrows). Some of the proteins slowly moved over the surface before they bound to a calcite step (white arrows). In the close-up view (rectangle in K) the trace of the protein (white arrows A–K) is shown. All images presented were taken in contact mode at a scan rate of 4 Hz and 512 pixels per line. Cantilevers with a force constant of 0.03 N/m were used. Frames A and K were 50 min apart.

These observations showed that perlwapin bound specifically to step edges of the ( ) plane and inhibited the growth of the calcite crystal in saturated calcium carbonate solution.

) plane and inhibited the growth of the calcite crystal in saturated calcium carbonate solution.

DISCUSSION

As part of an ongoing research program to isolate and identify the major components of the soluble organic matrix of the nacreous layer of the abalone (H. laevigata) shell, we identified a new protein, which we called perlwapin. The soluble matrix obtained after demineralization with acetic acid was fractionated by ion exchange chromatography and reversed phase HPLC. Among the proteins identified by N-terminal sequence analysis of the resulting peaks was perlwapin, the sequence analysis of which showed the protein to consist of three consecutive WAP or four-disulfide core domains. This type of domain, which comprises 40–50 amino acids and includes a characteristic eight cysteine motif (22), derives its name from a widespread major mammalian milk protein, whey acidic protein (WAP), which contains two or three of these domains (23). Although the function of these milk proteins remains unknown, many other proteins containing homologous domains have been identified as proteinase inhibitors, as, for instance, the members of the trappin family (24). Some WAP domain protease inhibitors also have antimicrobial activity (25) but there seem to exist also WAP domain proteins with antimicrobial activity only (26). Other WAP domains seem to inhibit ion transport. The porcine intestine SPAI proteins inhibit Na+/K+-ATPase (27), whereas the guinea pig seminal vesicle caltrin-like proteins inhibit Ca2+-transport into spermatozoa (28).

A WAP domain has also been identified in lustrin A, a multidomain protein isolated from H. rufescens nacre (10), which is thought to act as part of the adhesive between nacre tablets (7). This 116-kDa protein contains a single WAP domain of unknown function at its C-terminus. In contrast to other WAP domains, that of lustrin A contains 10 cysteines instead of the regular set of 8. As shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1, the third WAP domain of perlwapin was especially similar to the WAP domain of lustrin A. Our data (Table 1) may indicate that perlwapin domain 1 is the most ancient of the four known Haliotis nacre WAP domains because it shows the least similarity to the other ones. Domain 3 and the lustrin WAP domain, however, may have originated from duplication of an ancestral perlwapin 3 domain relatively recently.

The AFM experiments showed that perlwapin molecules can adhere very strongly to certain areas of a calcite crystal surface. Single protein molecules binding to the edges of a crystal plane could be observed. Some molecules seemed to diffuse along the surface to areas where they finally bound and stayed. This indicates a specific interaction between the crystal and the protein. The nature of this interaction in aqueous solution (with relatively low ion concentrations) might be short ranged, as in electrostatic interactions, where a certain charge density guides the molecules to the binding or association areas. The images of the protein in the AFM experiment suggested perlwapin to be a small globular molecule with a diameter of ∼2 nm, which is in agreement with the molecular weight of the protein.

The aragonite crystals of nacre have a platy geometry which is thought to be due to an inhibition of crystal growth at the surface in the geological fast growing crystal direction (c axis). This inhibition is most probably caused by components of the organic matrix surrounding each aragonite tablet. Our observations indicated that perlwapin can act as a growth inhibitor for calcium carbonate crystals in saturated calcium carbonate solution in vitro and therefore may also be involved in the regulation of crystal growth in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We thank F. Siedler and B. Scheffer (MPI, Martinsried) for measuring masses and W. Strasshofer (MPI, Martinsried) for excellent technical assistance. This work would not have been possible without the generous gift of abalone shells from Fred Glasbrenner (Australian Abalone Export Pty. Ltd., Laverton North, Victoria, Australia 3026). The protein sequence data reported in this work will appear in the Uniprot Knowledgebase under the accession number P84811.

We thank the VolkswagenStiftung for supporting the project (L.T., M.F.).

Laura Treccani and Karlheinz Mann contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Fritz, M., and D. E. Morse. 1998. The formation of highly organized biogenic polymer/ceramic composite materials: the high-performance microlaminate of molluscan nacre. Curr. Opin. Coll. Surf Sci. 3:55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaplan, D. L. 1998. Mollusc shell structures: novel design strategies for synthetic materials. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 3:232–236. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treccani, L., S. Khoshnavaz, S. Blank, K. von Roden, U. Schulz, I. M. Weiss, K. Mann, M. Radmacher, and M. Fritz. 2003. Biomineralizing proteins with emphasis on invertebrate-mineralized structures. In Biopolymers, Vol. 8. S. R. Fahnestock and A. Steinbüchl, editors. Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany. 289–321.

- 4.Wilt, F. H., C. E. Killian, and B. T. Livingston. 2003. Development of calcareous skeletal elements in invertebrates. Differentiation. 71:237–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schäffer, T. E., C. Ionescu-Zanetti, R. Proksch, M. Fritz, D. A. Walters, N. Almquist, C. M. Zaremba, A. M. Belcher, B. L. Smith, G. D. Stucky, D. M. Morse, and P. K. Hansma. 1997. Does abalone nacre form by heteroepitaxial nucleation or by growth through mineral bridges? Chem. Mater. 9:1731–1740. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song, F., A. K. Soh, and Y. L. Bai. 2003. Structural and mechanical properties of the organic matrix layers of nacre. Biomaterials. 24:3623–3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith, B. L., T. E. Schäffer, M. Viani, J. B. Thompson, N. A. Frederick, J. Kindt, A. M. Belcher, G. D. Stucky, D. E. Morse, and P. K. Hansma. 1999. Molecular mechanistic origin of the toughness of natural adhesives, fibres and composites. Nature. 399:761–763. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zentz, F., L. Bédouet, M. J. Almeida, C. Milet, E. Lopez, and M. Giraud. 2001. Characterization and quantification of chitosan extracted from nacre of the abalone Haliotis tuberculata and the oyster Pinctada maxima. Mar. Biotechnol. 3:36–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss, I. M., C. Renner, M. G. Strigl, and M. Fritz. 2002. A simple and reliable method for the determination and localization of chitin in abalone nacre. Chem. Mater. 14:3252–3259. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen, X., A. M. Belcher, P. K. Hansma, G. D. Stucky, and D. E. Morse. 1997. Molecular cloning and characterization of lustrin A, a matrix protein from shell and pearl nacre of Haliotis rufescens. J. Biol. Chem. 272:32472–32481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss, I. M., S. Kaufmann, K. Mann, and M. Fritz. 1999. Purification and characterization of perlucin and perlustrin, two new proteins from the shell of the mollusc Haliotis laevigata. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 267:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mann, K., I. M. Weiss, S. André, H.-J. Gabius, and M. Fritz. 2000. The amino-acid sequence of the abalone (Haliotis laevigata) nacre protein perlucin. Detection of a functional C-type lectin domain with galactose/mannose specificity. Eur. J. Biochem. 267:5257–5264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blank, S., M. Arnoldi, S. Khoshnavaz, L. Treccani, M. Kuntz, K. Mann, G. Grathwohl, and M. Fritz. 2003. The nacre protein perlucin nucleates growth of calcium carbonate crystals. J. Microsc. 212:280–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss, I. M., W. Göhring, M. Fritz, and K. Mann. 2001. Perlustrin, a Haliotis laevigata (abalone) nacre protein, is homologous to the insulin-like growth factor-binding protein N-terminal module of vertebrates. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 285:244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira Mouriès, L., M.-J. Almeida, C. Milet, S. Berland, and E. Lopez. 2002. Bioactivity of nacre water-soluble organic matrix from the bivalve mollusk Pinctada maxima in three mammalian cell types: fibroblasts, bone marrow stromal cells and osteoblasts. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B132:217–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Binnig, G., C. F. Quate, and C. Gerber. 1986. Atomic force microscope. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56:930–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillner, P. E., A. J. Gratz, S. Manne, and P. K. Hansma. 1992. Atomic scale imaging of calcite growth and dissolution in real time. Geology. 20:359–362. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walters, D. A., B. L. Smith, A. M. Belcher, G. T. Paloczi, G. D. Stucky, D. E. Morse, and P. K. Hansma. 1997. Modification of calcite crystal growth by abalone shell proteins: an atomic force study. Biophys. J. 72:1425–1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson, J. B., G. T. Paloczi, J. H. Kindt, M. Michenfelder, B. L. Smith, G. D. Stucky, D. E. Morse, and P. K. Hansma. 2000. Direct observation of the transition from calcite to aragonite growth as induced by abalone shell proteins. Biophys. J. 79:3307–3312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann, K., and F. Siedler. 1999. The amino acid sequence of ovocleidin-17, a major protein of the avian eggshell calcified layer. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Int. 47:997–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kacher, C. M., I. M. Weiss, R. J. Steward, C. F. Schmidt, P. K. Hansma, M. Radmacher, and M. Fritz. 2000. Imaging microtubules and kinesin decorated microtubules using tapping mode atomic force microscopy in fluids. Eur. Biophys. J. 28:611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ranganathan, S., K. J. Simpson, D. C. Shaw, and K. R. Nicholas. 2000. The whey acidic protein family: a new signature motif and three-dimensional structure by comparative modeling. J .Mol.Graphics Mod. 17:106–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson, K. J., and K. R. Nicholas. 2002. The comparative biology of whey proteins. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia. 7:313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schalkwijk, J., O. Wiedow, and S. Hirose. 1999. The trappin gene family: proteins defined by an N-terminal transglutaminase substrate domain and a C-terminal four-disulfide core. Biochem. J. 340:569–577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiedow, O., J. Harder, J. Bartels, V. Streit, and E. Christophers. 1998. Antileukoprotease in human skin: an antibiotic peptide constitutively produced by keratinocytes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 248:904–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagiwara, K., T. Kikuchi, Y. Endo, Huqun, K. Usui, M. Takahashi, N. Shibata, T. Kusakabe, H. Xin, S. Hoshi, M. Miki, N. Inooka, Y. Tokue, and T. Nukiwa. 2003. Mouse SWAM1 and SWAM2 are antibacterial proteins composed of a single whey acidic protein motif. J. Immunol. 170:1973–1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Araki, K., J. Kuroki, O. Ito, M. Kuwada, and S. Tachibana. 1989. Novel peptide inhibitors (SPAI) of Na+,K+-ATPase from porcine intestine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 164:496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coronel, C. E., J. San Agustin, and H. A. Lardy. 1990. Purification and structure of caltrin-like proteins from seminal vesicle of the guinea pig. J. Biol. Chem. 265:6854–6859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dandekar, A. M., E. A. Robinson, E. Appella, and P. K. Qasba. 1982. Complete sequence analysis of cDNA clones encoding rat whey phosphoprotein: homology to a protease inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:3987–3991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]