Abstract

Background

Dendritic cells (DC) have been proposed to facilitate sexual transmission of HIV-1 by capture of the virus in the mucosa and subsequent transmission to CD4+ T cells. Several T cell subsets can be identified in humans: naïve T cells (TN) that initiate an immune response to new antigens, and memory T cells that respond to previously encountered pathogens. The memory T cell pool comprises central memory (TCM) and effector memory cells (TEM), which are characterized by distinct homing and effector functions. The TEM cell subset, which can be further divided into effector Th1 and Th2 cells, has been shown to be the prime target for viral replication after HIV-1 infection, and is abundantly present in mucosal tissues.

Results

We determined the susceptibility of TN, TCM and TEM cells to DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission and found that co-receptor expression on the respective T cell subsets is a decisive factor for transmission. Accordingly, CCR5-using (R5) HIV-1 was most efficiently transmitted to TEM cells, and CXCR4-using (X4) HIV-1 was preferentially transmitted to TN cells.

Conclusion

The highly efficient R5 transfer to TEM cells suggests that mucosal T cells are an important target for DC-mediated transmission. This may contribute to the initial burst of virus replication that is observed in these cells. TN cells, which are the prime target for DC-mediated X4 virus transmission in our study, are considered to inefficiently support HIV-1 replication. Our results thus indicate that DC may play a decisive role in the susceptibility of TN cells to X4 tropic HIV-1.

Background

Several CD4+ T cell subsets can be identified in humans: naïve T cells (TN) to mount an immune response to a variety of new antigens, and memory T cells to respond to previously encountered pathogens. TN cells preferentially circulate between blood and secondary lymphoid tissues, using high endothelial venules to enter lymph nodes [1]. The memory T cell pool comprises distinct populations of central memory (TCM) and effector memory T cells (TEM), characterized by distinct homing and effector function [2,3]. Like TN cells, TCM cells express CCR7 and CD62L, two receptors required for migration to T cell areas of secondary lymphoid tissue. They furthermore have limited effector function, but can proliferate and become TEM cells upon secondary stimulation with antigen, and therefore play a role in long term protection. TEM cells have lost CCR7 expression, and home to peripheral tissues and sites of inflammation to provide immediate protection against pathogens [2,3]. Consequently, TN and TCM cells are primarily found in blood and lymphoid tissue, whereas TEM cells are enriched in gut, liver and lung. Within the TEM cell subset, effector Th1 and Th2 cells are recognized, which are classified by different functional properties based on unique cytokine profiles. Th1 cells produce high levels of IFNγ and TNFβ, which is instrumental in cell-mediated immunity against intracellular pathogens like viruses. Th2 cells secrete a large variety of cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-9 and IL-13) that are crucial for the clearance of parasites, like helminths. Both types of effector cells play a role in the induction of a humoral (antibody) response against different extracellular pathogens [4].

Sexual transmission of HIV-1 involves the crossing of mucosal tissue by the virus, and several studies have shown that one of the very first cell types encountered are intraepithelial and submucosal dendritic cells (DC). Consequently, they have been proposed to facilitate HIV-1 transmission and infection [5-8]. DC are professional antigen presenting cells that sample the environment at sites of pathogen entry. Sentinel immature DC (iDC) develop into mature effector DC (mDC) upon activation by microorganisms or inflammatory signals, and migrate to the draining lymph nodes where they encounter and stimulate naïve Th cells [9,10]. DC are able to capture HIV-1 by a range of receptors, of which the best studied example is DC-SIGN [11]. Subsequent transmission to T cells takes place in lymph nodes via cell-cell contact through an 'infectious synapse' [12]. Additionally, DC can support local virus replication in T cells present in the mucosal tissue [7,8].

An increasing number of studies on HIV-1 and SIV demonstrate that the initial burst of viral replication takes place in CCR5+ CD4+ (effector) memory T cells in the lamina propria of mucosal tissues [13-18]. CCR5 and CXCR4 are the major co-receptors used by HIV-1, with CCR5 being the initial co-receptor used by the virus after transmission. This receptor is primarily expressed on the memory T cell subset and macrophages [19]. Over time, HIV-1 starts to use CXCR4 in some patients, thereby expanding its target cell repertoire to TN cells, coinciding with faster disease progression [20,21].

Because DC play an important role in HIV-1 pathogenesis, and TN, TCM and TEM cells have distinct functions and locations in the body, we set out to investigate the contribution of DC in infection of these T cell subsets. We found that CCR5-using (R5) HIV-1 is efficiently transmitted to TEM cells but not to TN cells. Transmission to TCM cells was of intermediate efficiency. Transmission to pure populations of Th1 or Th2 cells, or to an unbiased population containing both types (Th0) was equally efficient. The highly efficient R5 transfer to TEM cells suggests that mucosal (TEM) cells are an important target for DC-mediated transmission, which may contribute to the observed initial burst of virus replication in these cells. CXCR4-using (X4) HIV-1 could be transmitted to all T cell subsets, due to expression of CXCR4 on all subsets. Surprisingly, X4 HIV-1 was preferentially transmitted to TN cells, which are considered to inefficiently replicate X4 HIV-1 [22-24]. This study shows that co-receptor expression is a decisive factor for DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission, and more importantly, that DC may play a crucial role in making TN cells susceptible to X4 HIV-1 replication later in infection.

Results

T cell subsets differ in susceptibility to DC-mediated transmission of R5 and X4 HIV-1

To investigate whether different CD4+ T cell subsets differ in their susceptibility to DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission, we isolated by live sorting highly purified populations of CD45RA+ CD45RO- naïve T cells (TN) and CD45RA- CD45RO+ memory T cells from pure CD4+ T cells. Based on the expression of CCR7, a homing receptor for secondary lymphoid tissue, the memory pool was further divided in CCR7+ central memory T cells (TCM) and CCR7- effector memory T cells (TEM) [2,3]. We subsequently incubated DC with the R5 virus JR-CSF isolate or the X4 virus LAI isolate for 2 hr, followed by washing steps to remove unbound virus. After addition of the respective T cell subsets, we determined the transmission efficiency by measuring the accumulation of HIV-1 capsid protein p24 (CA-p24) in T cells by FACS. To prevent subsequent rounds of HIV-1 replication after transmission in this single-cycle transmission assay, we added an inhibitor of the viral protease (saquinavir, [25,26]).

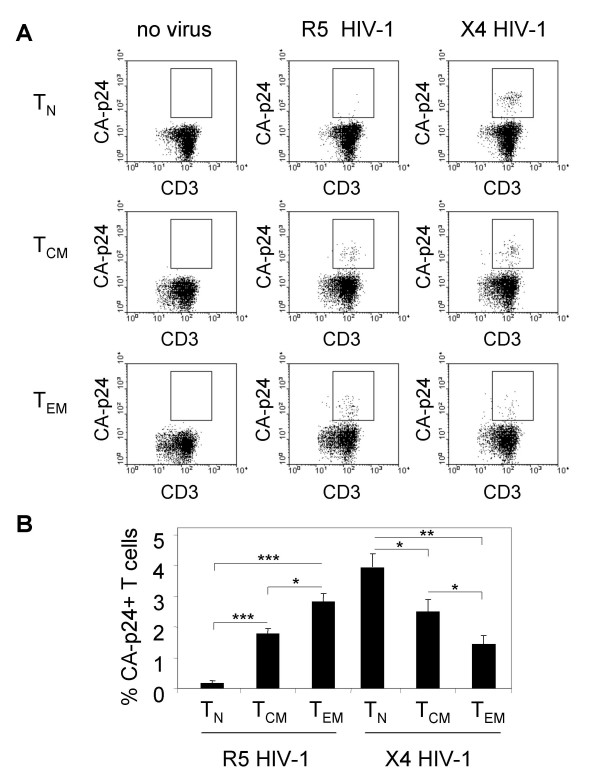

In a control experiment without HIV-1, no CA-p24 positive CD3+ T cells were scored (Fig. 1A). Addition of R5 HIV-1 resulted in high percentages of CA-p24+ TEM cells, and hardly any CA-p24+ TN cells (2.9 and 0.1 %, respectively). The transmission to TCM cells was of intermediate efficiency (1.9%). With X4 HIV-1, the pattern was reversed: X4 HIV-1 was preferentially transmitted to TN cells (4%), then to TCM cells (2.2%), and the transmission to TEM cells was least efficient (1.4%) (Fig. 1A). Overall, X4 transmission was more efficient than R5 transmission, and could take place to all subsets. For both viruses, the percentage CA-p24+ T cells reached a maximum value 2 days post transmission, and these data are quantified in Fig. 1B. This experiment demonstrates that there is not one exclusive T cell subset that is the preferred target of DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission, but that the efficiency depends on the tropism of the transmitted virus.

Figure 1.

T cell subsets differ in susceptibility to DC-mediated transmission of R5 and X4 HIV-1. (A) DC were incubated with R5 or X4 HIV-1, or mock treated, followed by extensive washing to remove unbound virus. DC were subsequently co-cultured with CD4+ naïve T cells (TN), central memory T cells (TCM) or effector memory T cells (TEM) in the presence of saquinavir to prevent spreading infection (single-cycle transmission assay). Two days after transmission, T cells were harvested and stained for CD3 and intracellular CA-p24 to determine the percentage HIV+ T cells. Representative FACS plots are shown. (B) Summary of one representative experiment. Error bars represent standard deviations. * p < 0.05 ; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission is co-receptor dependent

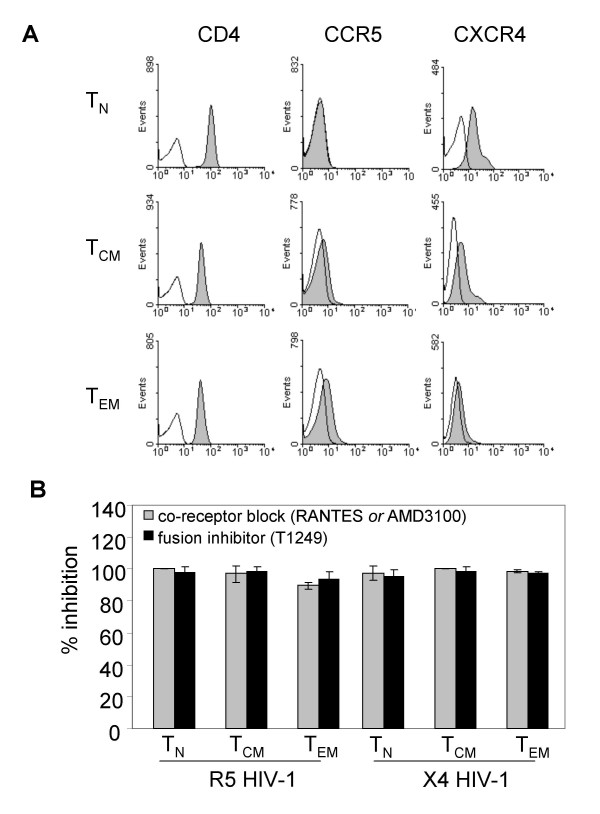

The different transmission patterns for R5 and X4 HIV-1 prompted us to investigate the co-receptor expression on each T cell subset (Fig. 2A). We found that the level of co-receptor expression for both CCR5 and CXCR4 correlates with the transmission efficiencies depicted in Fig. 1B: CCR5 expression is most pronounced on TEM cells, and is undetectable on TN cells; CXCR4 is detectable on all subsets, but its expression declines from TN cells via TCM to TEM cells.

Figure 2.

DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission is co-receptor dependent. (A) FACS analysis of TN, TCM and TEM cells for CD4 and co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4. Open histograms represent isotype controls. (B) Transmission inhibition by co-receptor ligands and a fusion inhibitor. A single-cycle transmission assay to TN, TCM and TEM cells was performed with R5 and X4 HIV-1 loaded DC. Prior to co-culture with DC, the T cells were pre-incubated with ligands for CCR5 (RANTES) or CXCR4 (AMD3100) (grey bars) or alternatively, with fusion inhibitor T1249 (black bars). After 2 days, the percentage CA-p24+ T cells was determined by FACS. The percentage inhibition of transmission relative to transmission without inhibitors is indicated on the y-axis. Error bars represent standard deviations.

To investigate the role of co-receptor expression in DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission, we added the well-described inhibitors RANTES and AMD3100 in the single-cycle transmission assay. These compounds inhibit HIV-1 infection of T cells by blocking the co-receptors CCR5 and CXCR4, respectively [27,28]. Transmission of HIV-1 was completely blocked through the addition of these compounds (Fig. 2B, grey bars). We furthermore could block transmission completely with inhibitor T1249 (Fig. 2B, black bars). This peptide prevents fusion of viral and cellular membranes [29]. Our results thus demonstrate that DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission requires 'regular' infection through CD4 and a co-receptor.

Method of T cell stimulation determines HIV-1 susceptibility

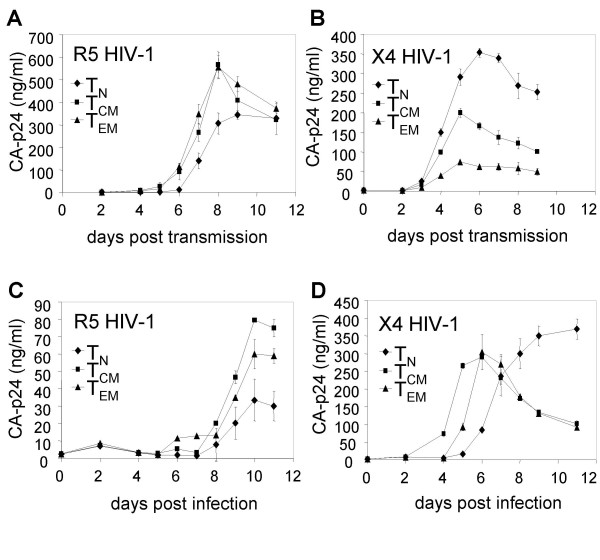

In addition to quantification of the transmission efficiency in a single-cycle transmission assay (Fig. 1 and 2), we followed viral replication after transmission (Fig. 3). In this spreading infection assay, we did not add saquinavir to allow cell-cell spread of newly produced virus. Replication of R5 and X4 HIV-1 in TN, TCM and TEM cells following DC-mediated transmission reflects the results of the single-cycle transmission assay: R5 HIV-1 preferentially replicates in memory T cells, whereas X4 HIV-1 prefers TN cells over the memory subsets (Fig. 3A and 3B).

Figure 3.

Spreading infection assay. Replication of R5 (A) and X4 (B) virus in TN, TCM and TEM cells after DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission. Alternatively, the T cell subsets were stimulated by crosslinking CD3/CD28 with antibodies and infected with R5 (C) or X4 (D) virus. Viral replication was followed by CA-p24 ELISA on the supernatant. Error bars represent standard deviations.

Since this spreading infection assay involves two different steps, i.e. transmission and subsequent replication, we also studied R5 and X4 HIV-1 replication in TN, TCM and TEM cells in a DC-independent system. Therefore, cellular proliferation was induced by cross linking of CD3 and CD28 on the T cells with antibodies (Fig. 3C and 3D). As expected, the susceptibility of all T cell subsets to R5 HIV-1 replication was low after CD3/CD28 stimulation. This phenomenon was previously described for CD4+ T cells in general, and is the consequence of CCR5 down regulation and production of natural CCR5 ligands that compete for co-receptor binding [30,31]. But despite this low replication capacity, the pattern of R5 replication was comparable to the replication after DC-mediated transmission of R5 HIV-1: replication was lower in TN cells. Surprisingly, X4 replication in TN cells was significantly delayed in comparison to TCM and TEM cells, which does not reflect the enhanced transmission and replication in TN cells in the transmission experiments (Fig. 1 and 3B).

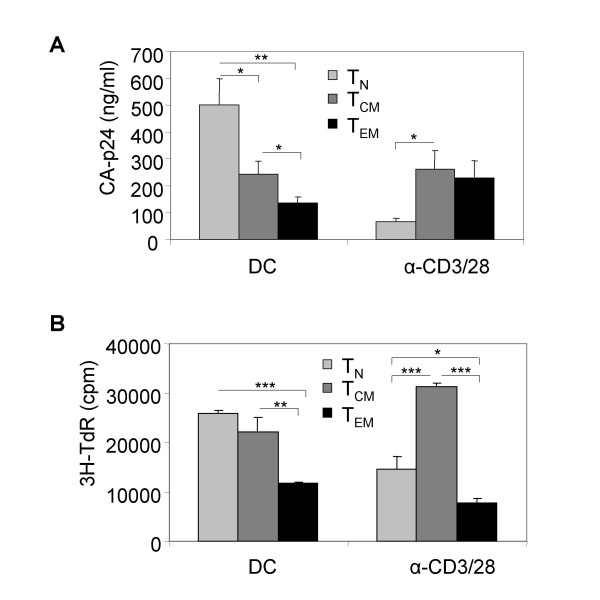

This discrepancy prompted us to compare HIV-1 replication in T cells stimulated by either DC or α-CD3/CD28 antibodies, without any complicating factors like transmission steps. We therefore stimulated all T cell subsets with DC, or alternatively, with α-CD3/CD28 antibodies and harvested the T cells after 4 days of proliferation. The cells were subsequently infected with X4 HIV-1. DC-stimulated TN cells were more susceptible to X4 HIV-1 replication than the memory subsets (Fig. 4A), which reflects the replication after transmission (Fig. 3B). The reverse was observed with α-CD3/CD28 stimulated T cells (Fig. 4A), which is in concordance with the results of Fig. 3D in which the cells were infected immediately after stimulation. This indicates that the enhanced replication of X4 HIV-1 in TN cells following DC-mediated transmission, is due to a higher HIV-1 susceptibility. It further demonstrates that crosslinking of CD3 and CD28 by antibodies is not comparable to DC-T cell stimulation, although this crosslinking is considered to mimic DC encounter. The difference between both stimulation methods is further manifested by the proliferative capacity of the T cells, as determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation (Fig 4B). The proliferation pattern of the different T cell subsets after DC or α-CD3/CD28 stimulation is clearly not the same.

Figure 4.

Method of T cell stimulation determines HIV-1 susceptibility. (A) Comparison of viral replication in TN, TCM and TEM cells that were stimulated by DC or by CD3/CD28 crosslinking with antibodies. The T cells were stimulated for 4 days, harvested and re-plated before infection with X4 HIV-1. Viral spread was followed by CA-p24 ELISA, of which the results of day 6 are shown. (B) To measure T cell proliferation TN, TCM or TEM cells were incubated with DC or α-CD3/CD28 antibodies and after 4 days, cellular proliferation was determined by 3H-thymidine incorporation. Error bars represent standard deviations. * p < 0.05 ; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

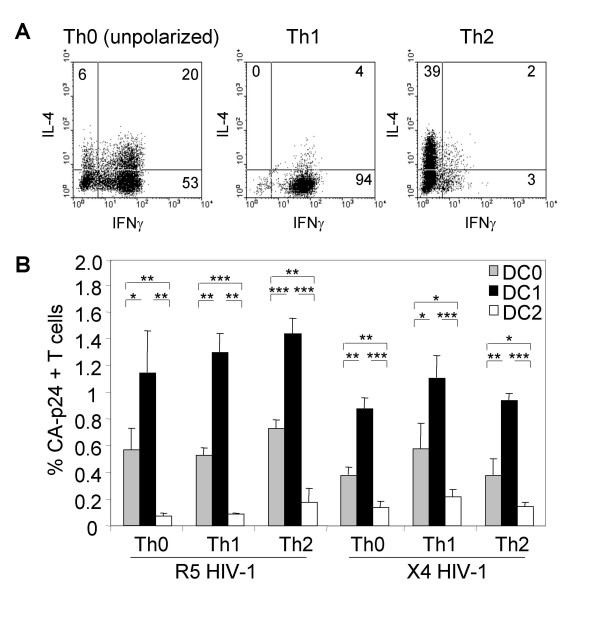

DC transmit HIV-1 with equal efficiency to Th1 and Th2 cells, or to an unpolarized population

The TEM cell subset can be further divided into effector Th1 and Th2 cells [4]. We generated in vitro polarized populations of pure Th1 and Th2 cells, or an unbiased population containing both types (Th0 cells), by culturing purified TN cells with or without IL-12 or IL-4, as previously described [32]. We next investigated whether HIV-1 is differently transmitted to these subsets of effector Th1, Th2 or Th0 cells. In addition, we tested different mature DC subsets. Depending on the type of pathogen and tissue factors, immature DC develop into mature effector DC that are specialized to stimulate naïve T cells to develop into IFNγ-producing Th1 cells or IL-4-producing Th2 cells, designated DC1 and DC2 respectively [33]. DC0 induce an unpolarized response (Th0). DC0, DC1 and DC2 were generated by culturing immature DC with maturation factors (MF, IL-1β and TNFα) only (DC0), or MF with either IFNγ (DC1) or prostaglandin E2 (DC2) [34].

The intracellular cytokine profiles of the effector Th cell populations were analyzed by FACS (Fig 5A). The Th1 population consists primarily of IFNγ producers, whereas the Th2 population contains mostly IL-4 producers. The unpolarized Th0 population is composed of both cell types. All T cell subsets expressed similar levels of CCR5 and CXCR4, and proliferated to a comparable extent, as determined by 3H incorporation (results not shown).

Figure 5.

DC transmit HIV-1 with equal efficiency to Th0, Th1 and Th2 cells. (A) In vitro generated polarized populations of Th1 and Th2 cells, or an unbiased population (Th0), were analyzed for intracellular cytokines IFNγ and IL-4 by FACS. The percentage single and double positive cells is indicated. (B) Th0, Th1 and Th2 cells were co-cultured with R5 or X4 virus-loaded DC in a single-cycle transmission assay to determine the transmission efficiency. Different DC subsets were used: DC1 that stimulate TN cells to develop into Th1 cells, DC2 that induce Th2 cells, or DC0 that induce an unpolarized response (Th0). The percentage CA-p24+ T cells was determined by FACS 2 days post transmission. Error bars represent standard deviations. * p < 0.05 ; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

DC0, DC1 and DC2 were subsequently incubated with R5 and X4 HIV-1, followed by washing and addition of Th0, Th1 and Th2 cells. Two days later, the transmission efficiency was determined in the single-cycle transmission assay (Fig. 5B). Consistent with Fig. 1B, R5 virus was a bit more efficiently transmitted to these polarized TEM cells than X4 HIV-1. More importantly, we found no significant differences in HIV-1 transmission efficiency to Th0, Th1 or Th2 cells within one DC subset, i.e. a particular DC subset transmits HIV-1 with equal efficiency to Th0, Th1 or Th2 cells. We also did not find a preference of HIV-1 transmission by a DC subset and its corresponding Th type: DC1 was the most efficient HIV-1 transmitter in all cases. The latter was previously demonstrated by us, using unpolarized peripheral blood leukocytes (PBL) and T cell lines [35]. We now show that this also applies to polarized Th subsets.

Discussion

TN, TCM and TEM cells have distinct functions and locations in the body [1,2], which may have, combined with the differential expression of HIV-1 co-receptors, an impact on HIV-1 transmission and infection. Since DC play an important role in HIV-1 pathogenesis, we studied the DC-mediated transmission of R5 and X4 virus to the different T cell subsets. Although we used only two (well-described) strains of HIV-1, our results suggest that in general R5 HIV-1 is preferentially transmitted to TEM cells, whereas DC transmit X4 HIV-1 most efficiently to the TN subset.

It is known that R5 viruses are primarily transmitted between individuals and that X4 viruses emerge only later in infection [19,36]. An increasing number of studies on HIV-1 and SIV demonstrate that the initial burst of viral replication takes place in CCR5+ CD4+ (effector) memory T cells in the lamina propria of the mucosa [13-18]. Later in infection, proviral DNA can be isolated from both naïve and memory CD4+ T cells [37,38]. The mechanism responsible for R5 predominance early in infection is not known. One proposed mechanism is the exclusive transport of R5 viruses over the epithelial barrier by epithelial CCR5+ cells [39]. Moreover, DC were proposed to be responsible due to the preferential replication of R5 HIV-1 [40-42], although this R5 replication is not entirely exclusive [43-46]. In addition, DC do not need to be productively infected to transmit HIV-1 to T cells [47,48], and DC can transmit both X4 as R5 HIV-1 to T cells [42]. In fact, we demonstrate in this study that X4 virus is generally transmitted more efficiently than R5 virus. Therefore, DC are probably not the 'gatekeepers' that select R5 viruses, although their role in sexual transmission is a crucial one [7,8].

One of the remaining questions is whether DC either facilitate local HIV-1 replication, or transport the virus to the lymph nodes, or both [7,8,19]. R5 HIV-1 is efficiently transmitted to TCM cells (Fig. 1), which are primarily present in lymphoid tissue, and even more efficiently to TEM cells, which are abundantly present at sites of viral entry in the mucosa. This suggests that transmission can take place at both locations.

Although X4 HIV-1 is very efficiently transmitted to TN cells, X4 virus does not emerge in recently infected HIV patients. Thus, DC-mediated X4 HIV-1 transmission to T cells may not take place following sexual transmission, or may not be a factor of relevance. DC may nonetheless play an important role later in infection (when X4 HIV emerges), e.g. by making TN cells susceptible to X4 HIV-1 as we have shown in this study.

We furthermore subdivided TEM cells into Th1 and Th2 cells, which did not reveal more differences. DC transmit HIV-1 with equal efficiency to Th1 or Th2 cells, or to an unbiased population containing both types (Th0). Reports on the ability of R5 and X4 virus to replicate in Th0, Th1 or Th2 cells are not univocal [49-52]. Based on our results, the type of TEM cell (Th0, 1 or 2) is not of importance for susceptibility to DC-mediated HIV-1 transmission, although the state of activation is an important (though not decisive) factor [53-55]. Furthermore, antigen specific T cells may be preferred [56].

We have shown here that the decisive factor for efficient HIV-1 transmission to the different T cell subsets is co-receptor expression. These HIV-1 transmission results with DC are in concordance with other studies that have shown in vivo and ex vivo the correlation between differential expression of CCR5 and CXCR4 on naïve and memory T cells and HIV-1 susceptibility [57-59]. We are the first to further divide the memory T cell pool into populations of effector and central memory T cells. We furthermore found that the presence of DC seems to enhance HIV-1 infection and replication, but does not change the pattern of susceptibility. Under certain conditions, no correlation was found between co-receptor expression and HIV-1 susceptibility. When the T cells were stimulated with α-CD3/CD28 antibodies, replication of X4 HIV-1 in TN cells was restricted in comparison to the memory subsets. We therefore compared stimulation of T cells by α-CD3/CD28 with stimulation by DC, and found differences in T cell proliferation and X4 susceptibility.

Crosslinking CD3 and CD28 by antibodies is a commonly used laboratory method for T cell stimulation, and mimics T cell activation through triggering of these molecules by DC-bound MHC-II and CD80/86, respectively. However, many more interactions play a role in DC-T cell interaction and stimulation, e.g. CD30L-CD30; OX40L-OX40; 41BBL-41BB; CD70-CD27; ICOSL-ICOS; CD40-CD40L and ICAM-1-LFA-1 [10,33,60,61]. Each of these interactions could have an influence on the replication capacity of HIV-1 in T cells, and some of these interactions therefore are the subject of further study. Our results demonstrate that DC play a vital role in priming TN cells to become susceptible to HIV-1, and that α-CD3/CD28 stimulation is not a very good model for DC stimulation in the context of HIV-1 studies.

Conclusion

We have shown that DC transmit R5 and X4 HIV-1 with different efficiencies to TN, TCM and TEM cells, and that this correlates with co-receptor expression of the different T cell subsets. The highly efficient transmission of R5 HIV-1 to TEM cells, which are abundantly present at sites of viral entry, may contribute to the observed burst of viral replication in these cells after HIV-1 infection. Later on in infection, DC may play an important role in the replication of X4 HIV-1 in TN cells.

Materials and methods

Generation of monocyte-derived dendritic cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated by density centrifugation on Lymphoprep (Nycomed, Torshov, Norway). Subsequently, PBMC were layered on a Percoll gradient (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) with three density layers (1.076, 1.059, and 1.045 g/ml). The light fraction with predominantly monocytes was collected, washed, and seeded in 24-well culture plates (Costar, Cambridge, MA, USA) at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well. After 60 min at 37°C, non-adherent cells were removed, and adherent cells were cultured to obtain immature DC in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM; Life Technologies Ltd., Paisley, United Kingdom) with gentamicin (86 μg/ml; Duchefa, Haarlem, The Netherlands) and 10% fetal calf serum (HyClone, Logan, UT, USA), supplemented with GM-CSF (500 U/ml; Schering-Plough, Uden, The Netherlands) and IL-4 (250 U/ml; Strathmann Biotec AG, Hannover, Germany). At day 3, the culture medium with supplements was refreshed. At day 6, maturation was induced by culturing the DC with maturation factors only (MF; IL-1β (10 ng/ml) and TNFα(50 ng/ml); Strathmann Biotec AG), or MF with either IFNγ (1000 U/ml; Strathmann Biotec AG), or prostaglandin E2 (10-6 M; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), see results for more details [34]. After two days, mature CD14- CD1b+ CD83+ DC were obtained. All subsequent tests were performed after harvesting and extensive washing of the cells to remove all factors. Mature DC were analysed for the expression of cell surface molecules on a FACScan (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Mouse anti-human mAbs were used against the following molecules: CD14 (BD Biosciences), CD1b (Diaclone, Besançon, France), CD83 (Immunotech, Marseille, France) and ICAM-1 (CD54) (Pelicluster, Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). All mAb incubations were followed by incubation with FITC-conjugated goat F(ab')2 anti-mouse IgG and IgM (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA).

CD4+ T cells

Naïve and memory T cells were live sorted from pure CD4+ T cells on a FACS ARIA (BD Biosciences). The following mouse-anti-human antibodies were used: CD45RA-FITC (Coulter, Hialeah, FL, USA), CD45RO-APC (BD Biosciences), CD4-PE-Cy7 (BD Biosciences). Rat-anti-human CCR7 (BD Biosciences) incubation was followed by biotin-rabbit-anti-rat (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and streptavidin-PerCp-Cy5.5 (BD Biosciences) incubation. CD4+ CD45RA+ CD45R0- cells were considered naïve T cells (TN). CD4+ CD45RA- CD45R0+ cells (the memory population) was separated into central memory (TCM) (CCR7+) and effector memory (TEM) (CCR7-) cells, according to the classification described by Sallusto et al [2]. Polarized Th1 and Th2 cells, and an unpolarized population containing both types (Th0 cells) were generated from purified TN cells as previously described [32]. In short, TN cells (105/200 μl) were stimulated with immobilized α-CD3 (CLB-T3/3; 1 μg/ml) and α-CD28 (CLB-CD28/1; 2 μg/ml) (both from Sanquin, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and cultured for 10 days in the absence (Th0) or presence of IL-12 (100 U/ml; a gift from Dr. M. K. Gately, Hoffma-La Roche) or IL-4 (1000 U/ml) for Th1 and Th2 cells respectively. To generate fully polarized Th cells, the cells were restimulated with PHA (10 μg/ml; Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) and 3000 rad-irradiated feeder cells (PBMC of two unrelated donors and EBV-B cells (JY cells)) in the presence of IL-4 for Th0 cells; IL-4 neutralizing antibodies (CLB_IL-4/6, Sanquin) plus IL-12 for Th1 cells; and IL-12 neutralizing antibodies (U-CyTech, Utrecht, the Netherlands) plus IL-4 for Th2 cells. All T cells were cultured in IMDM with 10% FCS, gentamycin and IL-2 (Cetus, Emeryville, CA, USA). During co-culture with DC, Staphylococcus enterotoxin B (SEB; Sigma-Aldrich; final concentration, 10 pg/ml) was added. α-CD3/CD28 stimulation of T cells for viral replication experiments was done with mouse mAb to human CD28 (CLB-CD28/1) and human CD3 (CLB-T3/4E-1XE, Sanquin).

Cytokine production by polarized Th cells

12 days after the second stimulation round, resting T cells were restimulated with PMA (10 ng/ml) and ionomycin (1 μg/ml) for 6 hr, the last 4.5 hr in the presence of Brefeldin A (10 μg/ml) (all Sigma-Aldrich). Cells were fixed in 2% PFA, permeabilized with 0.5% saponin (Sigma-Aldrich), and stained with anti-IFNγ -FITC and anti-IL4-PE (both BD Biosciences). Cells were then analysed by FACS.

Virus stocks

C33A cervix carcinoma cells were transfected using calcium phosphate with 5 μg of the molecular clone of CXCR4-using HIV-1 LAI or CCR5-using HIV-1 JR-CSF. The virus containing supernatant was harvested 3 days post transfection, filtered and stored at -80°C. The concentration of virus was determined by CA-p24 ELISA. C33A cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen, Breda, the Netherlands), supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM L-glutamine, penicillin (100 U/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml; Invitrogen).

HIV transmission assay and CA-p24 measurement

Fully matured DC (IFNγ/MF if indicated otherwise) were incubated in a 96-well-plate (45 × 103 DC/100 μl/well) with HIV-1 (15 ng CA-p24/well) for 2 hr at 37°C. The DC were washed with PBS after centrifugation at 400 × g to remove unbound virus. Washing was repeated 2 times, followed by addition of 50 × 103 TN, TCM or TEM cells. In some experiments, T1249 (250 ng/ml; Trimeris, Durham, NC, USA), RANTES (500 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) or AM3100 (10 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich) was added. The latter two were pre-incubated with the T cells for 30 min at 37°C. Prior to addition to DC, the T cells were analyzed by FACS with the following mouse anti-human antibodies: CD4-PE, CCR5-PE and CXCR4-PE (all BD Biosciences). Viral replication after transmission was followed by measuring CA-p24 in the culture supernatant by ELISA. To determine intracellular CA-p24 in the single-cycle transmission assay, saquinavir (Roche, London, UK at 0.2 μM) was added to prevent cell-to-cell spread of newly produced virions. After 48 hr, the T cells were harvested and stained with FITC-labeled CD3 (BD Biosciences), followed by fixation with 4% PFA and washing with washing buffer (PBS with 2 mM EDTA and 0.5% BSA). Fixated cells were then washed with perm/wash buffer (BD Biosciences), and incubated with PE-labeled CA-p24 (KC57-RD1, Coulter) followed by washing with successively perm/wash- and washing buffer. Cells were then analysed by FACS.

T cell proliferation

Fully matured DC (45 × 103 DC/well) were incubated in a 96-well-plate with TN, TCM, TEM cells, or polarized Th cells (50 × 103 T cells/well) in a final volume of 200 μl. After 2 days, cell proliferation was assessed by the incorporation of [3H]-TdR after a pulse with 13 KBq/well during the last 16 hr of the co-culture, as measured by scintillation spectroscopy. Alternatively, TN, TCM or TEM cells were stimulated with α-CD3/CD28 antibodies, followed by the [3H]-TdR pulse 2 days later.

Statistical analysis

Data were analysed for statistical significance (GraphPad InStat, Inc, San Diego, CA, USA) using ANOVA. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Competing interests

The author(s) declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FG designed the study, performed the experiments and wrote the paper; TMMVC participated in the proliferation assays, JHNS participated in the isolation of the T cell subsets, BB helped to write the manuscript, ECDJ designed the study and helped to write the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by grant 7008 from Aids Fonds Netherlands. We thank Rogier Sanders for helpful discussions, and Berend Hooibrink for helping us with FACS sorting.

Contributor Information

Fedde Groot, Email: info@feddegroot.nl.

Toni MM van Capel, Email: t.m.vancapel@amc.uva.nl.

Joost HN Schuitemaker, Email: j.schuitemaker@iqcorporation.nl.

Ben Berkhout, Email: b.berkhout@amc.uva.nl.

Esther C de Jong, Email: e.c.dejong@amc.uva.nl.

References

- Mackay CR, Marston WL, Dudler L. Naive and memory T cells show distinct pathways of lymphocyte recirculation. J Exp Med. 1990;171:801–817. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.3.801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallusto F, Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A. Central memory and effector memory T cell subsets: function, generation, and maintenance. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:745–763. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Understanding the generation and function of memory T cell subsets. Curr Opin Immunol. 2005;17:326–332. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbas AK, Murphy KM, Sher A. Functional diversity of helper T lymphocytes. Nature. 1996;383:787–793. doi: 10.1038/383787a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YK, Whelton KM, Mlechick B, Murphey-Corb MA, Reinhart TA. Productive infection of dendritic cells by simian immunodeficiency virus in macaque intestinal tissues. J Pathol. 2003;201:616–628. doi: 10.1002/path.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Gardner MB, Miller CJ. Simian immunodeficiency virus rapidly penetrates the cervicovaginal mucosa after intravaginal inoculation and infects intraepithelial dendritic cells. J Virol. 2000;74:6087–6095. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.13.6087-6095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland-Jones SL. HIV: The deadly passenger in dendritic cells. Curr Biol. 1999;9:R248–R250. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope M, Haase AT. Transmission, acute HIV-1 infection and the quest for strategies to prevent infection. Nat Med. 2003;9:847–852. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banchereau J, Briere F, Caux C, Davoust J, Lebecque S, Liu YJ, Pulendran B, Palucka K. Immunobiology of dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:767–811. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek TB, Kwon DS, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Middel J, Cornelissen IL, Nottet HS, KewalRamani VN, Littman DR, Figdor CG, van Kooyk Y. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;100:587–597. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald D, Wu L, Bohks SM, KewalRamani VN, Unutmaz D, Hope TJ. Recruitment of HIV and its receptors to dendritic cell-T cell junctions. Science. 2003;300:1295–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.1084238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehandru S, Poles MA, Tenner-Racz K, Horowitz A, Hurley A, Hogan C, Boden D, Racz P, Markowitz M. Primary HIV-1 infection is associated with preferential depletion of CD4+ T lymphocytes from effector sites in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2004;200:761–770. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kewenig S, Schneider T, Hohloch K, Lampe-Dreyer K, Ullrich R, Stolte N, Stahl-Hennig C, Kaup FJ, Stallmach A, Zeitz M. Rapid mucosal CD4(+) T-cell depletion and enteropathy in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1115–1123. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(99)70014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veazey RS, Tham IC, Mansfield KG, DeMaria M, Forand AE, Shvetz DE, Chalifoux LV, Sehgal PK, Lackner AA. Identifying the target cell in primary simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infection: highly activated memory CD4(+) T cells are rapidly eliminated in early SIV infection in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:57–64. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.23.11001-11007.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Duan L, Estes JD, Ma ZM, Rourke T, Wang Y, Reilly C, Carlis J, Miller CJ, Haase AT. Peak SIV replication in resting memory CD4+ T cells depletes gut lamina propria CD4+ T cells. Nature. 2005;434:1148–1152. doi: 10.1038/nature03513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P, Collins KB, Ratner D, Watkins S, Naus GJ, Landers DV, Patterson BK. Memory CD4(+) T cells are the earliest detectable human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-infected cells in the female genital mucosal tissue during HIV-1 transmission in an organ culture system. J Virol. 2002;76:9868–9876. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.19.9868-9876.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman Z, Meier-Schellersheim M, Paul WE, Picker LJ. Pathogenesis of HIV infection: what the virus spares is as important as what it destroys. Nat Med. 2006;12:289–295. doi: 10.1038/nm1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douek DC, Picker LJ, Koup RA. T cell dynamics in HIV-1 infection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2003;21:265–304. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor RI, Sheridan KE, Ceradini D, Choe S, Landau NR. Change in coreceptor use coreceptor use correlates with disease progression in HIV-1--infected individuals. J Exp Med. 1997;185:621–628. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van't Wout AB, Kootstra NA, Mulder-Kampinga GA, Albrecht-van Lent N, Scherpbier HJ, Veenstra J, Boer K, Coutinho RA, Miedema F, Schuitemaker H. Macrophage-tropic variants initiate human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection after sexual, parenteral, and vertical transmission. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2060–2067. doi: 10.1172/JCI117560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roederer M, Raju PA, Mitra DK, Herzenberg LA, Herzenberg LA. HIV does not replicate in naive CD4 T cells stimulated with CD3/CD28. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1555–1564. doi: 10.1172/JCI119318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, Levine BL, Craighead N, Francomano T, Kim D, Carroll RG, June CH. Naive and memory CD4 T cells differ in their susceptibilities to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection following CD28 costimulation: implications for transmission and pathogenesis. J Virol. 1998;72:8273–8280. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.8273-8280.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina CA, Prince HE, Richman DD. Preferential replication of HIV-1 in the CD45RO memory cell subset of primary CD4 lymphocytes in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1774–1785. doi: 10.1172/JCI119342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodawer A, Vondrasek J. Inhibitors of HIV-1 protease: a major success of structure-assisted drug design. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:249–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh L, Leung K, Lore K, Levin R, Panet A, Schwartz O, Koup RA, Nabel GJ. Infection of specific dendritic cells by CCR5-tropic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 promotes cell-mediated transmission of virus resistant to broadly neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2004;78:11980–11987. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.21.11980-11987.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donzella GA, Schols D, Lin SW, Este JA, Nagashima KA, Maddon PJ, Allaway GP, Sakmar TP, Henson G, De Clercq E, Moore JP. AMD3100, a small molecule inhibitor of HIV-1 entry via the CXCR4 co-receptor. Nat Med. 1998;4:72–77. doi: 10.1038/nm0198-072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway GP, Martin SR, Huang Y, Nagashima KA, Cayanan C, Maddon PJ, Koup RA, Moore JP, Paxton WA. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eron JJ, Gulick RM, Bartlett JA, Merigan T, Arduino R, Kilby JM, Yangco B, Diers A, Drobnes C, DeMasi R, Greenberg M, Melby T, Raskino C, Rusnak P, Zhang Y, Spence R, Miralles GD. Short-term safety and antiretroviral activity of T-1249, a second-generation fusion inhibitor of HIV. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:1075–1083. doi: 10.1086/381707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll RG, Riley JL, Levine BL, Feng Y, Kaushal S, Ritchey DW, Bernstein W, Weislow OS, Brown CR, Berger EA, June CH, St Louis DC. Differential regulation of HIV-1 fusion cofactor expression by CD28 costimulation of CD4+ T cells. Science. 1997;276:273–276. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley JL, Carroll RG, Levine BL, Bernstein W, St Louis DC, Weislow OS, June CH. Intrinsic resistance to T cell infection with HIV type 1 induced by CD28 costimulation. J Immunol. 1997;158:5545–5553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassink L, Vieira PL, Smits HH, Kingsbury GA, Coyle AJ, Kapsenberg ML, Wierenga EA. ICOS expression by activated human Th cells is enhanced by IL-12 and IL-23: increased ICOS expression enhances the effector function of both Th1 and Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:1779–1786. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.3.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinski P, Hilkens CM, Wierenga EA, Kapsenberg ML. T-cell priming by type-1 and type-2 polarized dendritic cells: the concept of a third signal. Immunol Today. 1999;20:561–567. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(99)01547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong EC, Vieira PL, Kalinski P, Schuitemaker JH, Tanaka Y, Wierenga EA, Yazdanbakhsh M, Kapsenberg ML. Microbial compounds selectively induce Th1 cell-promoting or Th2-cell promoting dendritic cells in vitro with diverse Th cell-polarizing signals. J Immunol. 2002;168:1704–1709. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders RW, de Jong EC, Baldwin CE, Schuitemaker JH, Kapsenberg ML, Berkhout B. Differential transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by distinct subsets of effector dendritic cells. J Virol. 2002;76:7812–7821. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.15.7812-7821.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger EA, Murphy PM, Farber JM. Chemokine receptors as HIV-1 coreceptors: roles in viral entry, tropism, and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:657–700. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankson JN, Persaud D, Siliciano RF. The challenge of viral reservoirs in HIV-1 infection. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53:557–593. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrowski MA, Chun TW, Justement SJ, Motola I, Spinelli MA, Adelsberger J, Ehler LA, Mizell SB, Hallahan CW, Fauci AS. Both memory and CD45RA+/CD62L+ naive CD4(+) T cells are infected in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1999;73:6430–6435. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.8.6430-6435.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng G, Wei X, Wu X, Sellers MT, Decker JM, Moldoveanu Z, Orenstein JM, Graham MF, Kappes JC, Mestecky J, Shaw GM, Smith PD. Primary intestinal epithelial cells selectively transfer R5 HIV-1 to CCR5+ cells. Nat Med. 2002;8:150–156. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece JC, Handley AJ, Anstee EJ, Morrison WA, Crowe SM, Cameron PU. HIV-1 selection by epidermal dendritic cells during transmission across human skin. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1623–1631. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.10.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canque B, Bakri Y, Camus S, Yagello M, Benjouad A, Gluckman JC. The susceptibility to X4 and R5 human immunodeficiency virus-1 strains of dendritic cells derived in vitro from CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitor cells is primarily determined by their maturation stage. Blood. 1999;93:3866–3875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granelli-Piperno A, Delgado E, Finkel V, Paxton W, Steinman RM. Immature dendritic cells selectively replicate macrophagetropic (M-tropic) human immunodeficiency virus type 1, while mature cells efficiently transmit both M- and T-tropic virus to T cells. J Virol. 1998;72:2733–2737. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2733-2737.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavrois M, Neidleman J, Kreisberg JF, Fenard D, Callebaut C, Greene WC. Human immunodeficiency virus fusion to dendritic cells declines as cells mature. J Virol. 2006;80:1992–1999. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.4.1992-1999.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanham G, Davis D, Willems B, Penne L, Kestens L, Janssens W, van der GG. Dendritic cells, exposed to primary, mixed phenotype HIV-1 isolates preferentially, but not exclusively, replicate CCR5-using clones. AIDS. 2000;14:1874–1876. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200008180-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchou I, Misery L, Sabido O, Dezutter-Dambuyant C, Bourlet T, Moja P, Hamzeh H, Peguet-Navarro J, Schmitt D, Genin C. Functional HIV CXCR4 coreceptor on human epithelial Langerhans cells and infection by HIV strain X4. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:313–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobile C, Petit C, Moris A, Skrabal K, Abastado JP, Mammano F, Schwartz O. Covert human immunodeficiency virus replication in dendritic cells and in DC-SIGN-expressing cells promotes long-term transmission to lymphocytes. J Virol. 2005;79:5386–5399. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.9.5386-5399.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turville SG, Santos JJ, Frank I, Cameron PU, Wilkinson J, Miranda-Saksena M, Dable J, Stossel H, Romani N, Piatak M, Lifson JD, Pope M, Cunningham AL. Immunodeficiency virus uptake, turnover, and two-phase transfer in human dendritic cells. Blood. 2003;103:2170–2179. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley RD, Gummuluru S. Immature dendritic cell-derived exosomes can mediate HIV-1 trans infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:738–743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507995103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahbouhi B, Landay A, Al Harthi L. Dynamics of cytokine expression in HIV productively infected primary CD4+ T cells. Blood. 2004;103:4581–4587. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikovits JA, Taub DD, Turcovski-Corrales SM, Ruscetti FW. Similar levels of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in human TH1 and TH2 clones. J Virol. 1998;72:5231–5238. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5231-5238.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moonis M, Lee B, Bailer RT, Luo Q, Montaner LJ. CCR5 and CXCR4 expression correlated with X4 and R5 HIV-1 infection yet not sustained replication in Th1 and Th2 cells. AIDS. 2001;15:1941–1949. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200110190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicenzi E, Panina-Bodignon P, Vallanti G, Di Lucia P, Poli G. Restricted replication of primary HIV-1 isolates using both CCR5 and CXCR4 in Th2 but not in Th1 CD4(+) T cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:913–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson M, Stanwick TL, Dempsey MP, Lamonica CA. HIV-1 replication is controlled at the level of T cell activation and proviral integration. EMBO J. 1990;9:1551–1560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08274.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zack JA. The role of the cell cycle in HIV-1 infection. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;374:27–31. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1995-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Schuler T, Zupancic M, Wietgrefe S, Staskus KA, Reimann KA, Reinhart TA, Rogan M, Cavert W, Miller CJ, Veazey RS, Notermans D, Little S, Danner SA, Richman DD, Havlir D, Wong J, Jordan HL, Schacker TW, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Letvin NL, Wolinsky S, Haase AT. Sexual transmission and propagation of SIV and HIV in resting and activated CD4+ T cells. Science. 1999;286:1353–1357. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lore K, Smed-Sorensen A, Vasudevan J, Mascola JR, Koup RA. Myeloid and plasmacytoid dendritic cells transfer HIV-1 preferentially to antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;201:2023–2033. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaak H, van't Wout AB, Brouwer M, Hooibrink B, Hovenkamp E, Schuitemaker H. In vivo HIV-1 infection of CD45RA(+)CD4(+) T cells is established primarily by syncytium-inducing variants and correlates with the rate of CD4(+) T cell decline. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:1269–1274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Rij RP, Blaak H, Visser JA, Brouwer M, Rientsma R, Broersen S, Roda Husman AM, Schuitemaker H. Differential coreceptor expression allows for independent evolution of non-syncytium-inducing and syncytium-inducing HIV-1. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1039–1052. doi: 10.1172/JCI7953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gondois-Rey F, Grivel JC, Biancotto A, Pion M, Vigne R, Margolis LB, Hirsch I. Segregation of R5 and X4 HIV-1 variants to memory T cell subsets differentially expressing CD62L in ex vivo infected human lymphoid tissue. AIDS. 2002;16:1245–1249. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200206140-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertram EM, Dawicki W, Watts TH. Role of T cell costimulation in anti-viral immunity. Semin Immunol. 2004;16:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2004.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauss P, Selz F, Cavazzana-Calvo M, Fischer A. Characteristics of antigen-independent and antigen-dependent interaction of dendritic cells with CD4+ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:2285–2294. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]