Abstract

The (S)-2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole) propionic acid (AMPA) receptor discriminates between agonists in terms of binding and channel gating; AMPA is a high-affinity full agonist, whereas kainate is a low-affinity partial agonist. Although there is extensive literature on the functional characterization of partial agonist activity in ion channels, structure-based mechanisms are scarce. Here we investigate the role of Leu-650, a binding cleft residue conserved among AMPA receptors, in maintaining agonist specificity and regulating agonist binding and channel gating by using physiological, x-ray crystallographic, and biochemical techniques. Changing Leu-650 to Thr yields a receptor that responds more potently and efficaciously to kainate and less potently and efficaciously to AMPA relative to the WT receptor. Crystal structures of the Leu-650 to Thr mutant reveal an increase in domain closure in the kainate-bound state and a partially closed and a fully closed conformation in the AMPA-bound form. Our results indicate that agonists can induce a range of conformations in the GluR2 ligand-binding core and that domain closure is directly correlated to channel activation. The partially closed, AMPA-bound conformation of the L650T mutant likely captures the structure of an agonist-bound, inactive state of the receptor. Together with previously solved structures, we have determined a mechanism of agonist binding and subsequent conformational rearrangements.

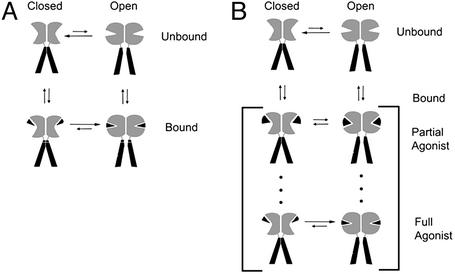

Ligand-gated ion channels are allosteric proteins composed of agonist binding and ion channel domains (1). Agonists do work on the ion channel by coupling the energy derived from agonist binding to the opening or gating of the ion channel. By definition, full agonists produce maximal activation of the ion channel, whereas partial agonists result in submaximal activation, even when applied at saturating concentrations. There are two distinct models to describe the behavior of allosteric proteins such as ligand-gated ion channels: a two-state or concerted model (2) and an induced-fit or multistate model (3, 4) (Fig. 1). In the two-state model, the ligand-gated ion channel exists in two conformations, an inactive or “apo” conformation and an agonist-bound, activated conformation. Full and partial agonists can bind to both states, with full agonists more effectively stabilizing the activated state in comparison with partial agonists (5). Thus, full agonists produce greater activation of the ion channel than partial agonists. Cyclic-nucleotide gated ion channels from bovine rod photoreceptors respond maximally to cGMP but only weakly to cAMP and are paradigms of the two-state model (5, 6).

Figure 1.

Mechanisms to describe the conformational behavior of ligand-gated ion channels. (A) The two-state model where the receptor is in equilibrium between two conformations, closed and open. Agonist binding stabilizes the receptor in the open state. Full agonists stabilize the open state more effectively than partial agonists, and both types of agonists stabilize the same conformational states. (B) Multistate model where the agonist-binding region of the receptor adopts a range of agonist-dependent conformations. Partial agonists promote a submaximal conformational change and therefore are not as effective in shifting the closed to open equilibrium of the ion channel to the open state.

According to the multistate hypothesis, the ligand-gated ion channel can adopt a range of conformations that depends on the particular agonist (Fig. 1B). Full agonists stabilize a conformation that maximally activates the ion channel and partial agonists stabilize different conformations that are less efficacious in channel activation; i.e., for partial agonists less binding energy is available for doing work necessary to open the ion channel gate. Using the GluR2 (S)-2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole) propionic acid (AMPA)-sensitive ion channel, we have studied the relationships between the conformation of the agonist-binding domain and activation of the ion channel by “tuning” ion channel gating via a specific combination of a partial agonist and a site-directed mutant in the agonist binding site.

AMPA receptors (GluR1–4) are a subtype of the ionotropic glutamate receptor family of ligand-gated ion channels (7, 8) and have a high affinity for the full agonist AMPA and a low affinity for the partial agonist kainate (9–11). AMPA receptors also bind and activate in response to the nonselective, full agonists l-glutamate and quisqualate (9–12). Crystallographic studies reveal that full and partial agonists bind to the cleft of the “clamshell-shaped” GluR2 S1S2J ligand-binding core (12–15): The full agonists AMPA, glutamate, and quisqualate bring the domains of the ligand-binding core ≈21° closer together, relative to the apo state, whereas the partial agonist kainate induces only 12° of domain closure (14). Kainate induces only partial domain closure because its isopropenyl group acts like a “foot in the door,” colliding with Tyr-450 and Leu-650. On the basis of these structural studies, we suggest that the ligand-binding core can adopt multiple, agonist-dependent conformations and that differences in agonist efficacy at AMPA receptors can arise from different conformations of the ligand-binding core.

To test this hypothesis, we reasoned that if the steric clash between the isopropenyl group of kainate and neighboring residues in the ligand-binding core were reduced, then kainate binding should induce greater domain closure and therefore be able to do more work on the ion channel; i.e., kainate should become an agonist with greater efficacy. Because mutation of the conserved Tyr-450 residue to smaller residues resulted in nonfunctional ligand-binding core protein, we focused our studies on residue 650. In fact, mutation of the equivalent residue in GluR1, Leu-646 to Thr (L646T), produces a decrease in the kainate EC50 and an increase in the extent of kainate current potentiation by cyclothiazide, suggesting that kainate is both a more potent and strongly desensitizing agonist when acting on the L646T mutant, in comparison with the WT receptor (16). In addition, leucine is conserved at position 650 in AMPA receptors, whereas in kainate receptors, which respond maximally to kainate but weakly to AMPA, the residue is either a valine or an isoleucine. Here we report complementary functional and structural studies of the Leu-650 to Thr (L650T) mutant of the GluR2 receptor, illuminating relationships between agonist binding, domain closure, and ion channel activation.

Materials and Methods

Molecular Biology.

The S1S2J constructs (14) were derived from the GluR2 (flop) gene (17), whereas the unedited GluR2 or GluRB (flip) gene (10), in the pGEM-HE expression vector (32), was used in the physiology. The L650T mutation was incorporated into the GluR2 S1S2J, GluR2 S1S2J L483Y, and full-length constructs (14, 18) by using the QuikChange protocol (Stratagene) and the primers 5′-ATGGAACAACCGACTCTGGATCCACTAAAG-3′ and 5′-GTGGATCCAGAGTCGGTTGTTCCATAAGCA-3′. The correct clones were confirmed by sequencing both strands of the DNA.

Physiology.

The ovaries of tricaine (3 g/liter)-anesthetized Xenopus laevis were surgically removed and placed in 30 ml of Barth's solution, cut into small pieces, and incubated for 60 min at 25°C with 1.5 mg/ml collagenase. Defolliculated oocytes were rinsed and stored in 88 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM NaHCO3, 1.1 mM KCl, 0.4 mM CaCl2, 0.3 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.3, and 5 μg/ml gentamicin at 18°C. Stage V and VI oocytes were injected with 0.5–2.0 ng of GluR2-L483Y, GluR2-L483Y/L650T, GluR2-L650T, or WT GluR2 in vitro-transcribed cRNA, and recordings were done 3–5 days later.

Recordings were performed in the two-electrode voltage-clamp configuration by using agarose-tipped microelectrodes (0.4–1.0 MΩ) filled with 3 M KCl. The holding potential was −60 mV. The bath solution contained 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 0.7 mM BaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, and 5 mM Hepes, pH 7.3. Rundown was corrected by measuring the response to a saturating concentration of glutamate in the beginning, middle, and end of the agonist applications. Cyclothiazide was added from a 0.1 M stock, in DMSO, to both bath and agonist solutions for a final concentration of 100 μM. For the maximal current measured at saturating agonist concentration (Imax) experiments, all agonists were applied to the same oocyte, and the responses elicited by glutamate were normalized to 1.0. In experiments that required concentrations of agonist >1 mM, a uniform osmolarity was maintained by addition of sodium chloride to solutions with lower concentrations of agonist. The data were acquired and processed by using the program synapse. Dose–response curves were plotted and fit to the Hill equation in kaleidagraph.

Crystallization.

The GluR2 S1S2J L650T and S1S2J L483Y/L650T proteins were expressed and purified as described (19, 20). All crystals were grown by hanging drop vapor diffusion at 4°C. S1S2J L650T was cocrystallized with 20 mM kainate over a reservoir solution containing 24–28% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 4000 and 0.2–0.35 M ammonium sulfate (AS). The two crystal forms for the S1S2J L650T/AMPA and L650T/quisqualate complexes were obtained with 12–16% PEG 8000, 0.1–0.3 M zinc acetate, and 0.1 M cacodylate, pH 6.5 (Zn form), or with 14–18% PEG 4000 and 0.2–0.4 M AS (AS form). S1S2J L483Y/L650T was cocrystallized with 20 mM AMPA by using 14–18% PEG 4000 and 0.2–0.4 M AS as precipitant. Crystals were cryoprotected with mother liquors supplemented with 14–18% glycerol before flash cooling in liquid nitrogen.

Crystallography.

All data sets were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source beamline X4A (Upton, NY) by using a Quantum 4 charge-coupled device detector except for the L650T/AMPA (Zn form) data set, which was collected at ×25 on a Brandeis B4 charge-coupled device detector. Data sets were indexed and merged by using the hkl suite (21). The S1S2J L650T/kainate, AMPA (AS form), quisqualate (AS form), and the S1S2J L483Y/L650T/AMPA structures were solved by molecular replacement using amore (22) with the S1S2J kainate protomer, S1S2J AMPA dimer, S1S2J quisqualate monomer, and S1S2J AMPA dimer structures as the search probes, respectively (12, 14). The S1S2J L650T/quisqualate(Zn) and L650T/AMPA(Zn) crystal forms were refined beginning from the WT structures by using x-plor (23) and cns (24). The protocols included rigid-body refinement, simulated annealing, Powell minimization, individual B-value refinement, and bulk-solvent modeling. After every round of refinement, the model was manually compared with the electron density by using omit maps, and the model was manually fit to the electron density. Refinement continued until the crystallographic R factors converged for the S1S2J L650T/kainate, quisqualate (AS form), and AMPA (AS form) structures. Refinements of the S1S2J L650T/AMPA (Zn form), quisqualate (Zn form), and S1S2J L483Y/L650T/AMPA structures were carried out until it was clear that the refined structures were essentially identical to the starting model.

Agonist Affinity Measurements.

Measurements of agonist Kd values were carried out by fluorescence spectroscopy using previously established methods (25, 26). The protein was dialyzed extensively against 10 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4) to reduce the concentration of glutamate. Three milliliters of freshly filtered protein was placed in a quartz cuvette maintained at 4°C by a circulating water bath. The protein concentration used varied by agonist (0.05–1 μM) so as to keep the protein concentration at least 2-fold below the Kd. The excitation wavelength was 280 nm and emission was detected at 330 nm with bandpasses of 4 nm and 8 nm, respectively. Small aliquots of agonist (1–10 μl) were added to the desired final concentration and the total volume of added ligand was <1%. The small dilution of starting solution was ignored. After each addition of agonist, the sample was thoroughly mixed by pipetting and the fluorescence at 330 nm was measured. The fluorescence change at each agonist concentration was measured five times and recorded as the average. The fluorescence at each point was calculated as

|

where Fo is the fluorescence from protein alone and Fn is the fluorescence after the nth addition of ligand. The ΔFs were fit to the Hill equation, with the Hill coefficient set equal to 1.0, by using kaleidagraph. Measurements were performed in duplicate or triplicate.

Results and Discussion

L650T Inverts the Relative Potency of AMPA and Kainate Responses.

To measure the extent of receptor activation, we used the nondesensitizing variant of GluR2, the Leu-483 to Tyr (L483Y) mutant (18, 27) as the WT species and introduced the L650T mutation in the L483Y background (L483Y/L650T) for two-electrode voltage–clamp experiments. Dose–response analysis of the L483Y and L483Y/L650T receptors in the presence of kainate, glutamate, AMPA, or quisqualate (Fig. 2) shows that the L650T mutation increases the EC50 values, decreasing the potencies of glutamate, quisqualate, and AMPA 8.5-, 66-, and 70-fold, respectively, relative to L483Y (Table 1). By contrast, the EC50 for kainate decreased 2.7-fold from 173 to 65 μM, indicating an increase in potency. The shifts in EC50 values were mirrored by changes in Kd values for binding of the same ligands to the isolated L650T ligand-binding core: The Kd values for glutamate, quisqualate, and AMPA increase 13-, ≈170-, and ≈500-fold, respectively, whereas the Kd for kainate decreases ≈12-fold (see Table 1 and Fig. 7, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site, www.pnas.org). The reduction in affinity of the GluR2 ligand-binding core for glutamate, quisqualate, and AMPA upon substitution of Leu-650 for Thr results, at least in part, from loss of nonpolar contacts made by the leucine side chain that span the cleft between domain 1 and domain 2 (13, 14). Substitution of the leucine by a smaller, polar side chain precludes formation of similar interactions, destabilizing the agonist-bound, closed-cleft conformation of the ligand-binding core. As described below, the L650T mutation increases kainate affinity because it allows for further domain closure, relative to the WT ligand-binding core.

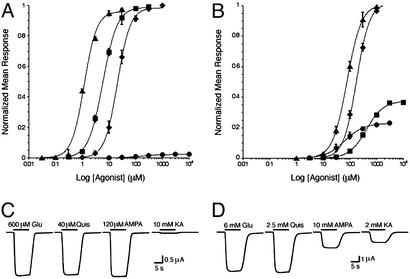

Figure 2.

Dose–response curves and Imax traces for the L483Y and L483Y/L650T variants of the full-length GluR2 receptor recorded by using the two-electrode, voltage–clamp technique. (A) Normalized dose–response curves for glutamate (Glu) (⧫), AMPA (■), quisqualate (Quis) (▴), and kainate (KA) (●) measured from oocytes expressing GluR2 L483Y receptors. (B) EC50 data for the GluR2 L483Y/L650T mutant, in combination with glutamate (⧫), AMPA (■), quisqualate (▴), or kainate (●), scaled for efficacy relative to glutamate. (C) Maximal currents (Imax) elicited by L483Y receptors and saturating concentrations of agonist. The duration of agonist application is indicated by horizontal, thick black lines, and the identity and concentration of the agonist is indicated above each line. (D) Maximum currents mediated by L483Y/L650T receptors. The Imax measurements were made on five individual oocytes. All values are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Agonist potency, efficacy, and affinity

| Agonist | WT

|

L650T

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50, μM | Hill | L483Y efficacy | CTZ efficacy | Affinity, μM | EC50, μM | Hill | L483Y efficacy | CTZ efficacy | Affinity, μM | |

| Glu | 20.8 ± 0.64 | 1.82 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.821* | 177 ± 9.2 | 1.77 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 6.61 ± 0.58 |

| Quisqualate | 1.18 ± 0.10 | 1.85 | 0.98 | 1.01 | 0.010† | 78.2 ± 1.0 | 1.61 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 1.74 ± 0.05 |

| AMPA | 5.88 ± 0.12 | 1.37 | 0.99 | 1.16 | 0.025* | 412 ± 26.4 | 1.37 | 0.38 | 0.31 | 12.8 ± 0.56 |

| Kainate | 173 ± 9.02 | 1.21 | 0.02 | 0.17 | 1.94 | 64.7 ± 4.1 | 1.21 | 0.24 | 0.45 | 0.16 ± 0.02 |

EC50 values and Hill coefficients were calculated from dose–response curves measured from GluR2-L483Y or GluR2-L483Y/L650T. To calculate relative agonist efficacy, the maximal current response was scaled to the value for glutamate, which was normalized to 1.0.

For the WT GluR2 S1S2J ligand-binding core where the value for AMPA is the Kd and the values for glutamate and kainate are IC50 measurements in competition with 3H AMPA (14).

IC50 value for the WT GluR2 S1S2J ligand-binding core in competition with 3H AMPA (30).

To test whether the substitution of leucine by threonine at position 650 altered the ability of glutamate, quisqualate, AMPA, or kainate to activate the ion channel, we measured the maximal current elicited by saturating concentrations of agonist (Imax). As shown in Fig. 2, L483Y receptors had similar maximal responses to glutamate, quisqualate, and AMPA, whereas the kainate-induced currents were 2.0% of those elicited by glutamate. L483Y/L650T receptors also had similar Imax values for glutamate and quisqualate. By contrast, the currents evoked by kainate in the L483Y/L650T receptor were 24% as large as those elicited by glutamate, suggesting that kainate is an ≈10-fold more efficacious agonist upon reduction of the size of the side chain at 650 from a leucine to a threonine.

Surprisingly, the L650T mutation changes AMPA to a partial agonist, and, in the context of L483Y/L650T, saturating concentrations of AMPA only activate the receptor to 38% of the maximal response produced by glutamate and quisqualate. To ensure that the L483Y and L483Y/L650T Imax data were not distorted by the L483Y mutation, we repeated the experiments with the WT GluR2 receptor and the L650T point mutant, using cyclothiazide to block desensitization (Table 1; refs. 11, 28, and 29), and we obtained qualitatively similar results.

Nevertheless, we did find a substantial difference between the relative Imax measurements of kainate-elicited currents in the context of L483Y versus the WT receptor plus cyclothiazide. As shown in Table 1, kainate results in currents that are 17% of the glutamate currents for the WT receptor/cyclothiazide combination, whereas kainate acting on the L483Y variant yields currents that are 2% of those evoked by glutamate. Therefore, we suggest that cyclothiazide may more effectively block desensitization in comparison with the L483Y mutant. Indeed, previous experiments carried out on native heteromeric AMPA receptors have shown that kainate currents are ≈37% of the magnitude of glutamate currents in the presence of cyclothiazide (11), and fast-perfusion measurements of kainate and glutamate activation of GluR3-L507Y (18, 27) showed that the ratio of peak kainate to peak glutamate currents ranged from ≈0.13 to ≈0.25. These data provide additional support for the conclusion that in the oocyte experiments reported here the agonist responses in the context of the L483Y mutant may be submaximal because of a modest extent of receptor desensitization.

L650T Increases Domain Closure Produced by Kainate.

To determine the effect of the L650T mutation on the structure of the ligand- binding core, we determined crystal structures of the kainate, AMPA, and quisqualate complexes by x-ray crystallography and compared them with the corresponding structures of the WT ligand-binding core. The structures of all complexes were determined to a resolution of 2.0 Å or higher (see Table 3 and Figs. 8 and 9, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site) and were subject to thorough refinement, as summarized in Table 2. As predicted by the physiology data, the extent of domain closure in the L650T S1S2J/kainate complex is greater than the degree of domain closure in the WT S1S2J/kainate complex. Shown in Fig. 3 is a superposition of the L650T and WT kainate cocrystal structures. We find that the L650T/kainate structure is 15° more closed than the WT Apo(A) structure and 5° more open than the WT AMPA(A) structure (14). By contrast, the WT S1S2J/kainate structure is 12° more closed than Apo(A) and 8° more open than AMPA(A) (14).

Table 2.

S1S2J L650T refinement statistics

| Complex | dmin | Rwork* | Rfree† | No. protein atoms | No. water | Mean B | rms deviations

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonds, Å | Angle, ° |

B values

|

||||||||

| Bond | Angle | |||||||||

| Kainate | 1.6 | 23.5 | 25.2 | 1,918 | 123 | 18.3 | 0.0062 | 1.41 | 1.18 | 1.83 |

| AMPA(AS) | 2.0 | 23.7 | 27.2 | 3,868 | 177 | 15.9 | 0.0055 | 1.24 | 1.39 | 1.98 |

| AMPA(Zn) | 2.0 | 21.7 | 27.0 | 5,891 | 421 | 16.7 | 0.0065 | 1.31 | 1.20 | 1.95 |

| Quisqualate(AS) | 1.6 | 20.4 | 23.5 | 1,953 | 220 | 11.2 | 0.0052 | 1.19 | 1.10 | 1.80 |

| L483Y-AMPA | 1.8 | 23.4 | 26.4 | 3,875 | 235 | 17.8 | 0.0055 | 1.22 | 1.38 | 1.84 |

Rwork = (∑ ∥Fo| − |Fc∥)/∑ |Fo|, where Fo and Fc denote observed and calculated structure factors, respectively.

Ten percent of the reflections in each data set was set aside for the calculation of the Rfree value.

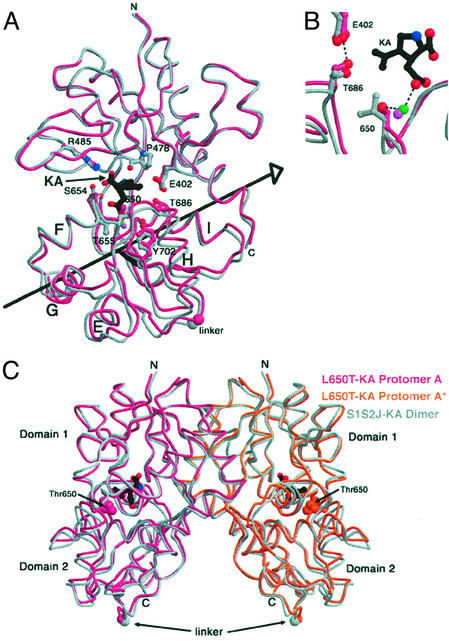

Figure 3.

Comparison of the WT and S1S2J L650T/kainate conformations. (A) Superimposition of WT and L650T/kainate structures. The WT backbone is drawn in gray and the mutant structure is shown in magenta. Kainate is drawn in black. Selected binding cleft side chains are drawn in ball-and-stick representation and colored as the backbone. The large spheres at the bottom of the structure depict the location of the first residue (Gly) in the two residue Gly-Thr linker. (B) Close-up view of superimposed WT and mutant kainate (KA) binding sites. The green sphere is a water in the mutant structure and the purple sphere is a water in the WT structure. In the mutant structure, the hydroxyl of Thr-650 makes a water-mediated hydrogen bond with kainate that is absent in the WT structure. In the L650T/kainate structure, two key residues situated on the clamshell cleft move 0.6 Å closer together relative to the WT kainate structure, placing the hydroxyl of Thr-686 in ideal hydrogen bonding distance (2.6 Å) to a carboxylate oxygen of Glu-402. (C) Superimposed S1S2J/kainate and L650T/kainate crystallographic dimers. WT protomers are drawn in gray and mutant protomers are shown in magenta (A) and orange (A*-symmetry related protomer). Thr-650 is drawn in space-filling mode.

The L650T mutation allows for greater domain closure in the kainate complex because the smaller threonine side chain minimizes the steric clash between the isopropenyl group of kainate and the larger leucine side chain present in the WT receptor. Specifically, the α-carbon of Thr-650 moves ≈0.8 Å farther into the binding cleft relative to the α-carbon of Leu-650. The relocation of Thr-650 is coupled to a rigid body movement of most of domain 2, resulting in a 3° increase in domain closure in the L650T/kainate complex, relative to the WT S1S2J/kainate structure. Because the ligand-binding cores of AMPA receptors are arranged as back-to-back dimers, domain closure is coupled to an increase in the distance between the “linker” regions, proximal to the ion channel gate (18). Therefore, the increase in domain closure in the L650T/kainate complex translates into an increase in linker separation of ≈1.0 Å, relative to the WT kainate complex (Fig. 3C). We suggest that in the intact L483Y/L650T receptor, kainate binding results in greater domain closure, together with greater linker separation, and this in turn is coupled to an increase in efficacy of channel gating. Determining whether the increase in kainate induced currents in the L483Y/L650T receptor, relative to glutamate and quisqualate, is caused by an increase in open probability or single-channel conductance, or both, will require in-depth single-channel analysis.

AMPA Is a Partial Agonist in the Context of L650T.

To address this unexpected result, we analyzed crystal structures of the L650T mutant in complexes with AMPA or quisqualate. Strikingly, the crystallographic analysis of multiple crystal forms reveals that the L650T/AMPA complex adopts multiple conformations that range from partially closed with ≈11° of domain closure relative to the WT Apo subunit to fully closed conformations with 21–22° of domain closure. In the cocrystals of L650T/AMPA grown in the presence of AS, there are two molecules in the asymmetric unit related by a noncrystallographic twofold axis, one of which adopts the partially (≈11°) closed conformation (molecule B) whereas the other is fully closed (molecule A), similar to the WT S1S2J/AMPA complex. Illustrated in Fig. 4 are superpositions of the WT S1S2J/AMPA and L650T S1S2J/AMPA structures. To determine whether other L650T/AMPA conformations could be observed in different crystal forms, we solved the structure of a second crystal form that contains three molecules in the asymmetric unit (Zn form), and we crystallized and solved the structure of the L483Y/L650T S1S2J/AMPA double mutant, which has two molecules in the asymmetric unit. For both of the crystal forms, the extent of domain closure in the ligand-binding core was 21–22°, similar to the WT AMPA complex.

Figure 4.

Comparison of WT and S1S2J L650T/AMPA(AS) conformations. (A) Superposition of WT S1S2J/AMPA (gray) with S1S2J L650T/AMPA (AS form) protomer A (blue). (B) Superposition of WT S1S2J/AMPA (gray) with S1S2J L650T/AMPA(AS) protomer B (green). The black arrows in A and B indicate the axis of rotation relating the conformational difference between the WT and L650T structures. (C) Superimposed WT and mutant AMPA dimers.

To directly compare the crystallographic studies of the L650T/AMPA complex to the corresponding complex with glutamate or quisqualate, we determined the cocrystal structure of the L650T/quisqualate species under crystallization conditions that were essentially identical to those used to grow the AS and Zn crystal forms of L650T/AMPA. We focused on the L650T/quisqualate complex because it more readily produced diffraction-quality crystals in comparison with the glutamate complex. In addition, structural analysis of the WT GluR2 S1S2J/quisqualate complex has shown that quisqualate is a bona fide isostere of glutamate (30) and in the present study we found that quisqualate acted as a full agonist on GluR2 L650T mutant receptors. All of the refined L650T/quisqualate structures show full domain closure and are similar to the previously determined WT quisqualate structure (data not shown). Therefore, with respect to domain closure, the L650T/quisqualate structure is similar to the WT AMPA and glutamate structures.

Our crystallographic analyses suggest that AMPA is a partial agonist at the L650T receptor, relative to glutamate and quisqualate, because the L650T mutation has dramatically destabilized the closed-cleft, AMPA-bound conformation. This, in turn, allows for the L650T/AMPA receptor to populate conformations that have different, submaximal degrees of domain closure. Instead of one low-energy conformation dominating the L650T/AMPA free energy spectrum, which would be the conformation with full domain closure in the case of the WT receptor, there are at least two conformations, one with ≈11° and a second with ≈21° of domain closure. The multiple conformations of the ligand-binding core result in submaximal AMPA currents, because the conformers with <21° of domain closure do not allow the ligand-binding core to do as much work on the ion channel in comparison with the conformers that possess full domain closure.

Linker Separation Is Correlated to Channel Activation.

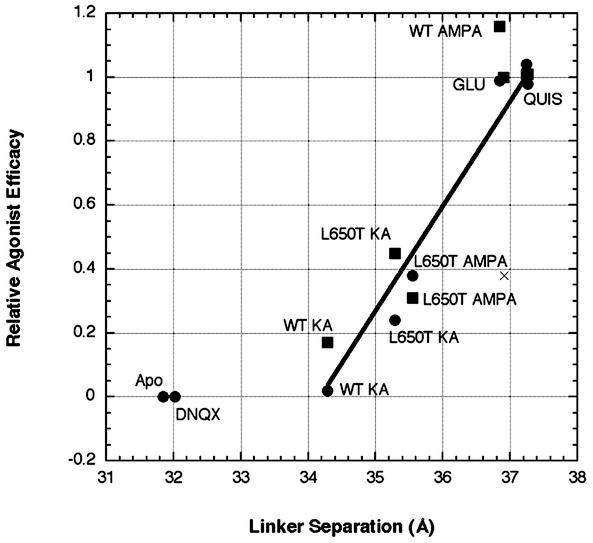

Illustrated in Fig. 5 is a graph showing the correlation between linker separation and Imax values for the WT and L650T variants of the GluR2 receptor with full and partial agonists, as well as the apo- and antagonist-bound forms. As the extent of linker separation increases from ≈34.3 Å in the WT/kainate dimer to ≈37.2 Å in the WT AMPA, quisqualate, and glutamate dimer (18), the relative Imax values also increase from 0.02 to 1.0. A simple linear fit to the points associated with the full and partial agonists yields a striking correlation, thus strengthening the concept that domain closure and linker separation are coupled to the activation of the ion channel and that agonists that yield maximal domain closure and linker separation produce maximal activation of the ion channel.

Figure 5.

Correlation between linker separation and agonist efficacy. The values for relative agonist efficacy were determined for L483Y receptors (●) and WT receptors in the presence of 100 μM cyclothiazide (■) and are listed in Table 1. Apo and 6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (DNQX) are assumed to have an efficacy of zero, and the other values are scaled to glutamate, which is set to one. Linker separation is defined as the distance between Gly Cα atoms from the artificial Gly-Thr linker joining S1 and S2. The structure corresponding to each point is indicated. The L650T/AMPA(Zn) structure is indicated with an ×. The glutamate (Glu) and quisqualate (Quis) points are all clustered around an efficacy of 1.0. The agonist-bound data points were fit with a linear equation that yields a correlation coefficient of 0.893. KA, kainate.

Mechanism of Agonist Binding and Domain Closure.

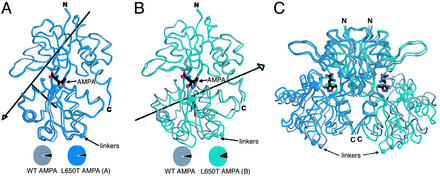

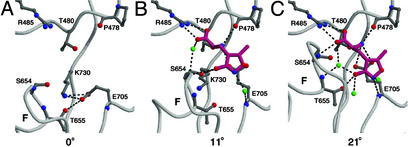

The partially closed conformation seen in subunit B of the L650T/AMPA (ammonium sulfate form) complex fortuitously affords a view of a putative agonist-bound, closed-channel state. AMPA is bound primarily to residues in domain 1, making contacts to domain 1 that are essentially identical to those made upon full domain closure. However, AMPA only makes one direct and three water-mediated interactions to domain 2, in comparison with the three direct and three water-mediated interactions made upon full domain closure. The partially closed L650T/AMPA subunit structure, in conjunction with previously determined structures, allows us to piece together a mechanism for agonist binding to the resting, closed-channel state of the receptor and for the subsequent conformational rearrangements in the ligand-binding core. Shown in Fig. 6 is an illustration of this process, which is also seen in Movie 1, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

Figure 6.

Mechanism of agonist binding and domain closure. (A) The binding site of the open-cleft, closed-channel state (Apo S1S2J, protomer A). (B) The possible first step in agonist binding as observed in molecule B of the L650T/AMPA(AS) structure. We suggest that this semiclosed cleft conformation represents the agonist-bound, closed-channel state. (C) The closed-cleft, open-channel conformation as observed in the WT S1S2J/AMPA binding cleft (protomer A). In B and C, water molecules are shown as green spheres, AMPA is drawn in magenta, and hydrogen bonds are depicted by black dashed lines. The degrees of domain closure relative to the Apo conformation are indicated below each structure.

The proposed mechanism for AMPA binding and ensuing conformational changes is as follows. In the resting, inactive state, the ligand-binding cleft is open, the ion channel is closed, and the carboxylate of Glu-705 interacts with the hydroxyl group of Thr-655 at the base of helix F and the amino group of Lys-730 (14). Initially, AMPA binds to the ligand-binding core via interactions with preorganized residues on domain 1 and the carboxylate of Glu-705 moves from the base of helix F to bind to the amino group of AMPA, thus opening up the anion binding site at the base of helix F for the isoxazole ring of AMPA or the γ-carboxylate of glutamate. As revealed in molecule B of the L650T/AMPA structure, the isoxazole ring of AMPA initially contacts the hydroxyl of Ser-654 and the ligand-binding core closes by ≈11°. After the formation of this initial complex, domain 2 moves toward domain 1, increasing the extent of domain closure to ≈21°, allowing for the formation of additional direct receptor contacts with AMPA, and trapping the agonist in the binding pocket (25). We suggest that this final rearrangement of domain 2 is the primary conformational change induced by AMPA that is coupled to the gating or opening of the ion channel.

Conclusions

Understanding the function, mechanism, and symmetry of allosteric proteins necessarily requires structural information. In the case of ligand-gated ion channels there are, at the present time, no atomic resolution structures of a ligand-gated ion channel in apo- and agonist-bound states. Our structural studies on the GluR2 ligand-binding core, while not including the ion channel domain, nevertheless demonstrate that the agonist- binding region can adopt a range of agonist-dependent conformations, thus suggesting that AMPA receptors are best described by an induced-fit, multistate model. The extent to which other ligand-gated ion channels, such as cyclic-nucleotide- gated channels and members of the acetylcholine receptor family (31), conform to a two-state versus a multistate model must await further structural and functional investigations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Joe Lidestri is gratefully acknowledged for the direction and maintenance of the x-ray laboratory at Columbia University. Craig Ogata is thanked for assistance with data collection at X4A at the National Synchrotron Light Source, and Carla Glasser provided valuable assistance with the physiology experiments. We thank Cinque Soto for assembling the S1S2J L650T construct. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (to M.M. and E.G.), the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (to E.G.), and the Jane Coffin Childs Memorial Fund for Medical Research (to N.A.). E.G. is an Assistant Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and a Klingenstein Research Fellow.

Abbreviations

- AMPA

(S)-2-amino-3-(3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole) propionic acid

- AS

ammonium sulfate

- Imax

maximal current measured at saturating agonist concentration

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.rcsb.org (PDB ID codes 1P1N, 1P1O, 1P1Q, 1P1U, and 1P1W).

References

- 1.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monod J, Wyman J, Changeux J P. J Mol Biol. 1965;12:88–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koshland D E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1958;44:98–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koshland D E, Nemethy G, Filmer D. Biochemistry. 1966;5:365–385. doi: 10.1021/bi00865a047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Zagotta W N, Lester H A. Q Rev Biophys. 1997;30:177–193. doi: 10.1017/s0033583597003326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Varnum M D, Black K D, Zagotta W N. Neuron. 1995;15:619–625. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90150-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis S F. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madden D R. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:91–101. doi: 10.1038/nrn725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Honoré, T. & Drejer, J. (1988) Excitatory Amino Acids Health Dis. 91–106.

- 10.Keinänen K, Wisden W, Sommer B, Werner P, Herb A, Verdoorn T A, Sakmann B, Seeburg P H. Science. 1990;249:556–560. doi: 10.1126/science.2166337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patneau D K, Vyklicky L, Mayer M L. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3496–3509. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-08-03496.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jin, R. & Gouaux, E. (2003) Biochemistry, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Armstrong N, Sun Y, Chen G-Q, Gouaux E. Nature. 1998;395:913–917. doi: 10.1038/27692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong N, Gouaux E. Neuron. 2000;28:165–181. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00094-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogner A, Kastrup J S, Jin R, Liljefors T, Mayer M L, Egebjerg J, Larsen I K, Gouaux E. J Mol Biol. 2002;311:815–836. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00650-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mano I, Lamed Y, Teichberg V I. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:15299–15302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.26.15299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulter J, Hollmann M, O'Shea-Greenfield A, Hartley M, Deneris E, Maron C, Heinemann S. Science. 1990;249:1033–1037. doi: 10.1126/science.2168579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun Y, Olson R A, Horning M, Armstrong N, Mayer M L, Gouaux E. Nature. 2002;417:245–253. doi: 10.1038/417245a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen G-Q, Gouaux E. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:9409–9419. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen G-Q, Sun Y, Jin R, Gouaux E. Protein Sci. 1998;7:2623–2630. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560071216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Otwinowsky Z, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navaza J. Acta Crystallogr A. 1994;50:157–163. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brünger A T. x-plor: A System for X-Ray Crystallography and NMR. New Haven, CT: Yale Univ. Press; 1992. , version 3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunger A T, Adams P D, Clore G M, DeLano W L, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve R W, Jiang J S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu N S, et al. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abele R, Keinänen K, Madden D R. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21355–21363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909883199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Misulovin Z, Bjorkman P J. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:481–490. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stern-Bach Y, Russo S, Neuman M, Rosenmund C. Neuron. 1998;21:907–918. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80605-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Partin K M, Patneau D K, Winters C A, Mayer M L, Buonanno A. Neuron. 1993;11:1069–1082. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90220-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamada K, Tang C-M. J Neurosci. 1993;13:3904–3915. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-09-03904.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin R, Horning M, Mayer M L, Gouaux E. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15635–15643. doi: 10.1021/bi020583k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karlin A. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrn731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liman E R, Tytgat J, Hess P. Neuron. 1992;9:861–871. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90239-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.