Abstract

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy contamination of the human food chain most likely resulted from nervous system tissue in mechanically recovered meat used in the manufacture of processed meats. We spiked hot dogs with 263K hamster-adapted scrapie brain (10% wt/wt) to produce an infectivity level of ≈9 log10 mean lethal doses (LD50) per g of paste homogenate. Aliquots were subjected to short pressure pulses of 690, 1,000, and 1,200 MPa at running temperatures of 121–137°C. Western blots of PrPres were found to be useful indicators of infectivity levels, which at all tested pressures were significantly reduced as compared with untreated controls: from ≈103 LD50 per g at 690 MPa to ≈106 LD50 per g at 1,200 MPa. The application of commercially practical conditions of temperature and pressure could ensure the safety of processed meats from bovine spongiform encephalopathy contamination, and could also be used to study phase transitions of the prion protein from its normal to misfolded state.

Keywords: food processing‖scrapie‖bovine spongiform encephalopathy‖ new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease‖prion disease

Since 1995, over 140 patients with variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease have died as a probable result of having consumed processed meat products contaminated by the agent of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in mechanically recovered meat (MRM) that contained vertebral column nervous tissue. Although almost all cases have occurred in Great Britain, France and Italy have had indigenous cases, and future cases may appear in any country in which BSE exists.

Governments in Europe, as elsewhere, have taken steps to minimize the risk of exposure to BSE, both in terms of breaking the cycle of animal exposure to halt the spread of disease among cattle, and of prohibiting potentially infectious cattle tissue from entering the human food chain. However, implementation of these precautions has not been uniform, and regulatory strategies, even when implemented, require continuous inspection to assure compliance.

A complementary strategy based on the inactivation of infectivity in processed meat would therefore be an attractive further safeguard to human health, but neither of the two proven inactivating methods, autoclaving or exposure to strong alkali or bleach, are applicable to foodstuffs. In this paper we show that the level of infectivity in processed meat “spiked” with scrapie-infected brain is reduced by 103 to 106 mean lethal doses (LD50) per g of tissue when subjected to several short pulses of high pressure (690–1,200 MPa) at temperatures of 121–137°C.

Materials and Methods

Infectious Tissue.

The 263K strain of hamster-adapted scrapie was passaged in hamsters, and the brains of terminally ill animals were removed and stored at −70°C until use. Bioassays of brain tissue from earlier passage animals regularly yielded infectivity titers in the range of 9 log10LD50 per g.

Substrate Tissue.

Oscar Mayer brand hot dogs were purchased at a U.S. food store chain and brought to Europe at ambient temperature, where sample preparation was performed. Analysis showed 0.98 water activity (Aw), pH of 6.8, fat content of 30%, and salt level of 2.2%. Three hot dogs were mechanically homogenized for 3 min.

Sample Preparation.

Six grams of brain tissue were blended into 54 g of the hot dog paste with a further 3 min of mechanical homogenization to achieve a final 10% (wt/wt) concentration of brain in the hot dog substrate. Approximately 2-g quantities of the “spiked” hot dog homogenate were distributed into 0.75 mil nylon/2.25 mil (1 mil = 25.4 μm) polyethylene pouches, heat-sealed, repacked in 100 mm × 125 mm pouches (12-μm polyester outer layer; 15 μm of nylon, 12.5 μm of aluminum foil, 102 μm of polypropylene-inner layer), and heat sealed again. An undiluted aliquot of brain macerate used for the spikes was similarly packaged for testing.

Pressure Testing.

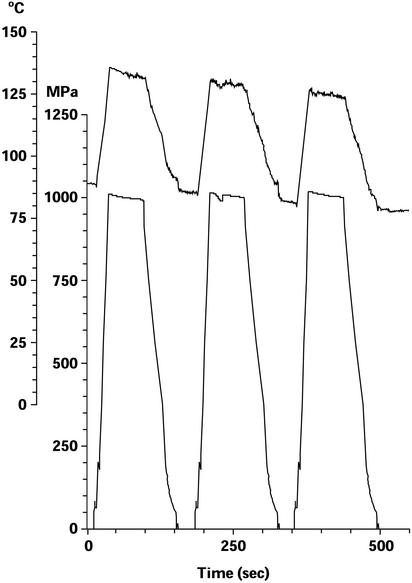

The sealed samples were immersed in polyethylene bottles filled with castor oil, brought to temperatures in the range of 80–90°C in a water bath, and then placed into the 1.8-liter capacity chamber of a high-pressure apparatus with an external heater (Avure, Vasteras, Sweden). This model achieves pressures as high as 1,450 MPa, with rapid compression and decompression times. The chamber was filled with water, sealed, and then subjected to pressures of 690 MPa (100,000 psi), 1,000 MPa (145,000 psi), or 1,200 MPa (174,000 psi) in a series of either 3 or 10 60-sec pulses, with 60-sec intervals of decompression. Chamber temperatures and pressures were continuously recorded during each test run (Fig. 1). After testing, samples were frozen at −40°C and transported to Rome, where Western blots and bioassays were performed.

Figure 1.

Example of pressure/temperature test run recording: three pulses of 1,000 MPa at a starting temperature of ≈85°C. Upper tracing shows temperature; lower tracing shows pressure. Adiabatic heating during pressure application raised the temperature by 50°C to ≈135°C during the first pressure pulse; heat loss through the chamber lowered the temperature of each succeeding pulse by ≈5°C.

To determine the contribution of heat to the pressure/heat inactivation, we also performed a carefully monitored autoclaving, in which an identically packaged sample was brought to 121°C in <1 min, autoclaved for 5 min (during which the temperature slowly rose to 134°C) and was then immediately brought back to subfreezing temperature in an ethanol–dry ice slurry.

Western Blot Immunoassays.

Aliquots of thawed brain macerate and spiked hot dog pastes were removed from the sealed pouches and prepared as follows.

Brain tissue.

Ten milligrams of the brain pool specimen were homogenized as a 10% (wt/vol) suspension in PBS, pH 7.4, and digested with proteinase K (final concentration = 50 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Digestion was terminated by the addition of 2 μl of 0.1 M PMSF (final concentration = 2 mM).

Hot dogs.

Ten milligrams of spiked hot dog paste were homogenized as a 10% (wt/vol) suspension in distilled water containing 10% sarkosyl, incubated 30 min at room temperature, and centrifuged at 22,000 × g for 20 min at 10°C. Supernatants were ultracentrifuged at 200,000 × g for 1 h at 10°C. Pellets were sonicated in 1% sarkosyl and then digested with proteinase K (final concentration = 10 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. Digestion was terminated by the addition of 2 μl of 0.1 M PMSF (final concentration = 2 mM).

SDS/PAGE and Western blotting.

Samples were suspended in NuPAGE gel loading buffer, heated for 10 min in a boiling water bath, and clarified by brief centrifugation. Supernatants were loaded onto a 12-well 12% Bis-Tris NuPAGE polyacrylamide gel and run according to manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Samples were tested in a series of half-log dilution steps. Electro-transfer to nitrocellulose membranes and immunostains (using a 1:2,000 dilution of 3F4 monoclonal anti-hamster PrPres antibody), were performed as described (2).

Duplicate sample aliquots were sent to the Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy (TSE) Group at Bayer Biological Products (Research Triangle Park, NC) for Western blot testing as described in their most recent publication (3).

Infectivity Bioassays.

A 0.3- to 0.5-g aliquot of each thawed sample was added to a sufficient volume of PBS to make a 10% wt/vol suspension, which was homogenized by using a Teflon-glass Potter tissue grinder and then serially diluted in one-log steps in PBS. Samples were inoculated into groups of four or more weanling hamsters: 50 μl of each sample were inoculated into the left cerebral hemisphere of each animal. Animals were observed for clinical signs of scrapie for 9 months. The brains of all dying animals, and of surviving animals in dilution groups at and above the highest positive dilution, were examined by Western blot for the diagnostic presence of PrPres.

Infectivity titers were calculated by using the method of Reed and Muench (4). For some titrations it was not possible to calculate a precise titer by this method, and in these cases we made what we considered a reasonable estimate based on the observed dilution series data. For example, the untreated spiked hot dog sample transmitted disease to all inoculated animals through the 10−7 dilution, and to three of four animals in the 10−8 dilution. Although the exact Reed–Muench 50% end point could not be calculated, the number of transmissions in the next (10−9) dilution would most likely have been either 0 or 1 of 4. These assumed values yield Reed–Muench titers of 108.3 and 108.5 per 0.03-ml inoculum.

For all such estimated end-points, we chose the most conservative values to minimize the degree of treatment infectivity reductions.

Results

Western blot data are shown in Table 1; bioassay data are shown in Table 2, and PrPres and infectivity clearance values are summarized in Table 3. Although the Bayer Western blot protocol was ≈100-fold more sensitive than the protocol used in our laboratory (allowing an expanded range of reduction values), both methods gave broadly similar results, and were useful predictors of the more costly and time consuming infectivity bioassays. Significant inactivation (2–3 log LD50 per g) occurred at the lowest tested pressure of 690 MPa, and higher levels of inactivation (4–6 log LD50 per g) were achieved at pressures of 1,000 and 1,200 MPa, whether using 3 or 10 1-min pulses. Even greater reductions were seen after exposure to a single 5-min 1,200 MPa pulse (6.3 log LD50 per g), or a 5-min exposure to steam autoclaving (≥6.7 log LD50 per g).

Table 1.

Western blots of brain tissue and spiked hot dog-brain mixtures under various test conditions

| Subject | Test conditions

|

Log10 dilution of sample (weights of brain loaded onto gel)

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure, MPa | Temperature, °C | Number of 1-min pulses | 0.5 (3 mg) | 1 (1 mg) | 1.5 (330 μg) | 2 (100 μg) | 2.5 (33 μg) | 3 (10 μg) | 3.5 (3.3 μg) | 4 (1 μg) | 4.5 (0.3 μg) | |

| Brain tissue | ||||||||||||

| Ambient | Ambient | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | |||

| 1,200 | 135 | 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||||

| Hot dogs | ||||||||||||

| Ambient | Ambient | 0 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | |||

| 1,200 | 135 | 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| 1,000 | 135 | 3 | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||||

| 690 | 124 | 3 | + | + | − | − | ||||||

| 1,200 | 135 | 10 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| 1,000 | 137 | 10 | − | − | − | − | − | − | ||||

| 690 | 121 | 10 | + | + | − | − | ||||||

| 1,200 | 142 | 1 (5 min) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||

| 0.2 | 121–134 | Autoclave (5 min) | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |||

Table 2.

Bioassays of brain tissue and spiked hot dog-brain mixtures under various test conditions

| Subject | Test conditions

|

Log10 dilution of sample (weights of brain loaded onto gel)

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure, MPa | Temperature, °C | Number of 1-min pulses | 1 (5 mg) | 2 (0.5 mg) | 3 (50 μg) | 4 (5 μg) | 5 (0.5 μg) | 6 (50 ng) | 7 (5 ng) | 8 (0.5 ng) | |

| Brain tissue | |||||||||||

| Ambient | Ambient | 0 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 0/4 | |||

| 1,200 | 135 | 3 | 4/4 | 3/3 | 5/5 | 2/4 | 0/3 | ||||

| Hot dogs | |||||||||||

| Ambient | Ambient | 0 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 6/6 | 7/7 | 4/4 | 3/4 | |||

| 1,200 | 135 | 3 | 3/4 | 0/4 | 1/4 | 0/3 | |||||

| 1,000 | 135 | 3 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | 1/5 | |||||

| 690 | 124 | 3 | 3/3 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | |||||

| 1,200 | 135 | 10 | 3/3 | 1/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |||||

| 1,000 | 137 | 10 | 2/4 | 1/4* | 1/4 | 1/4 | |||||

| 690 | 121 | 10 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 4/4 | 3/4 | |||||

| 1,200 | 142 | 1 (5 min) | 1/2 | 0/3 | 0/4 | 0/3 | |||||

| 0.2 | 121–134 | Autoclave (5 min) | 0/4 | 1/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | 0/4 | |||

Fractions represent positive over total number of inoculated animals.

The positive animal was unique in having a subclinical infection (documented by the presence of cerebral PrPres) when killed at the conclusion of the study. All other PrPres-positive animals were symptomatic, and in no other asymptomatic animal was PrPres detected in the brain.

Table 3.

Summary of PrPres and infectivity reductions in brain and brain-spiked hot dogs

| Subject | Test conditions

|

Log10 PrPres reduction

|

Log10LD50 per g

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure, MPa | Temperature, °C | Number of 1-min pulses | Rome | Bayer | Titer | Reduction | |

| Brain tissue | |||||||

| Ambient | Ambient | 0 | 8.8 | ||||

| 1,200 | 135 | 3 | ≥3.5 | 3 | 5.3 | 3.5 | |

| Hot dogs | |||||||

| Ambient | Ambient | 0 | ≈9.6 | ||||

| 1,200 | 135 | 3 | ≥3.5 | 4.5 | 3.8 | 5.8 | |

| 1,000 | 135 | 3 | ≥3.0 | 3.5 | 5.8 | 3.8 | |

| 690 | 124 | 3 | 1.5 | 2 | ≈6.8 | ≈2.8 | |

| 1,200 | 135 | 10 | ≥3.5 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 5.6 | |

| 1,000 | 137 | 10 | ≥3.0 | 4.5 | 3.9 | 5.7 | |

| 690 | 121 | 10 | 1.5 | 2 | ≈6.6 | ≈3.0 | |

| 1,200 | 142 | 1 (5 min) | ≥3.5 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 6.3 | |

| 0.2 | 121–134 | Autoclave (5 min) | ≥3.5 | NT | ≤2.9 | ≥6.7 | |

NT, not tested.

It should be noted that several of these infectivity reduction values were approximated because the end-point dilutions of some titrations were not fully bracketed; however, judging by decreasing transmission rates and increasing incubation periods, such titrations were very near their end points. For example, in the titrations of samples exposed to 690 MPa, animals in the highest tested dilution groups had incubation periods of 139–210 days, which were as long or longer than those of animals in the end-point dilution groups of the untreated positive controls (125–139 days), and at least double those of both treated and control animals in lower dilution groups, which ranged between 73–89 days.

The ≈1 log titer difference between the untreated positive controls (brain and brain-spiked hot dog) is consistent with the variability inherent in bioassays (typically in the range of ± 0.5 log). The 2 log greater reduction of infectivity at 1,200 MPa in the sample of brain diluted 1:10 in hot dog homogenate than in the sample of crude brain macerate is unexplained, but may be due to a greater inactivation of diluted than crude brain. The smaller infectivity reduction at 690 MPa than at the two higher pressures could have resulted either because of the lower pressure, or because the temperature rise due to adiabatic heating at this pressure did not achieve the same end temperature level as the higher pressures.

Discussion

The effect of high pressure on reducing the bacterial load in foodstuffs (thus enhancing preservation) was first examined >100 years ago (5), but was largely neglected until the past 15 years, when reliable high-pressure equipment was developed and introduced into commerce. A substantial literature has since accumulated on the use of pressure to inactivate a variety of bacterial, fungal, and viral pathogens (6). Generally speaking, the higher the pressure (and/or temperature) the better the result, although a few notable exceptions have been observed, such as an optimal inactivation temperature near 0°C for Listeria (7) and λ phage (8).

Bacterial endospores, the most durable of known conventional pathogens, resist inactivation in the range of pressures that kill vegetative bacteria or fungi, but are substantially inactivated when heated and then exposed to pressures ≥600 MPa. We have recently established a temperature/pressure checkerboard for the inactivation of several different spores, including Clostridium sporogenes and Bacillus subtilis (9).

Prions are even more resistant than endospores to standard inactivation methods such as heat, irradiation, and chemicals. Like the agent of BSE, the 263K strain of hamster-adapted scrapie chosen for the present experiment is particularly hardy: very small amounts of infectivity have been shown to survive steam autoclaving at 134°C (10), or dry heat up to 600°C (11). The 263K strain also proved to be unusually difficult to inactivate by pressure/heat combinations, with minimal survival under conditions that sterilize all other pathogenic agents. Nevertheless, a significant reduction of infectivity (2–3 log10LD50 per g) was observed in spiked hot dog meat at a pressure of 690 MPa, and it is probable that by compensating for the smaller adiabatic temperature rise with a higher initial temperature, so that the end temperature would reach that of the higher tested pressures (135°C), a greater infectivity reduction could be achieved.

Although steam autoclaving at temperatures in the range of 121–134°C will drastically reduce or eliminate infectivity in the absence of high pressure, and is the simpler method of inactivation, meats do not retain satisfactory flavor and/or texture when subjected to steam autoclaving. Thus, the need for a practical alternative, and a consideration of the question as to whether an infectivity reduction of 2–3 log10LD50 per g, achievable with 690 MPa, would be an adequate guarantee of safety.

The infectivity titer of brain, as measured by intracerebral (ic) inoculation of cattle, is ≈106 LD50 per g in an animal with clinical disease (12). Spinal cord and ganglia infectivity levels are slightly lower than brain, and oral infection requires at least 100 times more tissue than ic infection (13), so that it would be fair to estimate the oral dose infectivity of spinal cord and ganglia as not exceeding 104 LD50 per g (less, if there is any cattle to human species barrier to infection).

After manual removal of the head, viscera, long bones, and meat, the remaining carcass used for the production of MRM weighs ≈30 kg, of which ≈300 g is contributed by spinal cord and ≈30 g by paraspinal ganglia (the only remaining infectious tissues). The resulting dilution of nervous system infectivity by noninfectious tissue (1:100 or 1:1,000, depending on the presence or absence of spinal cord) is partially negated by an overall carcass to MRM concentration ratio of ≈5:1, resulting in an MRM infectivity level of 5 × 101 to 102 per g (50–500 LD50 per g).

The incorporation of MRM as an ingredient of processed meat is typically in the range of 10% by weight, further reducing infectivity to 5–50 LD50 per g. This would be the level of contamination if the MRM were entirely produced from BSE-infected cattle. However, the highest in-herd incidence of BSE never exceeded 10%, even at the height of the U.K. epidemic, so that the proportion of unaffected cattle in any given batch of carcasses would have resulted in at least another 10-fold dilution, yielding a maximum concentration of infectivity in the final product of 0.5–5 LD50 per g.

This estimate is still too generous, because the periodic consumption of 2-oz (60-g) hot dogs with this level of infectivity would have surely already caused far more than the ≈130 cases of disease so far seen in the British population. However, it underscores the point that the inclusion of a processing step that inactivated no more than 2 log10LD50 per g (100 LD50 per g) would provide a significant measure of safety from infection by BSE, and presumably from infection by other animal TSEs, such as chronic wasting disease of deer and elk. Commercially available 215-liter high-pressure machines capable of operating at 690 MPa can process up to 25 million tons annually, at a cost estimated to add only a few pennies per pound to the final product.

The present study is presented as a work in progress, to which a number of additional experiments will be added, or are already underway. In particular, we wish to explore a larger range of pressure/temperature/pulse combinations, and to verify the efficiency of inactivation for additional TSE strains (e.g., natural and experimentally adapted BSE, variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, and chronic wasting disease) in a variety of processed meat products (e.g., hamburger, pureed baby food, paté, meat broth, and pet food). Other kinds of potentially contaminated materials that do not withstand autoclaving might also retain biological integrity under short pressure/temperature pulses, such as Cohn fraction plasma pastes, reusable chromatography gels, or tissue culture meat broths, and it is even possible that instruments such as endoscopes could be successfully decontaminated without damage.

Although our primary focus has been the application of high pressure for purposes of disinfection, the method could also be used to investigate the kinetic and structural aspects of PrPres formation. The potential of high pressure to investigate protein misfolding diseases, including Alzheimer's disease and prion diseases, has been noted (14, 15), and there are reports of reversible disaggregation of transthyretin and amyloid A subjected to pressures of 350 and 1,200 MPa, respectively (16, 17). In another study, the normal form of the yeast prion (URE 2) suffered only limited structural change under pressures as high as 600 MPa (18).

We know of no previous reports of high-pressure technology applied to mammalian prions. Given the primacy of the misfolded protein in the pathogenesis of TSE, and the proven utility of high pressure to elucidate protein transitional states (19–21), the method could prove to be an interesting tool with which to probe prion protein misfolding, intermediate (“molten globule”) forms, and aggregation–disaggregation phenomena. It may even be possible to establish the minimum size and conformational profile of an infectious particle.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Huub Lelieveld (Unilever Corporation, Vlaardingen, The Netherlands) for use of the Vlaardingen Research Laboratory facility to prepare specimens; to Jan Hjelmqwist and other personnel of Avure Inc. (Vasteras, Sweden) for use of their facility and assistance in performing the pressure testing; to Dr. Loredana Ingrosso, Dr. Mei Lu, Maurizio Bonanno, and Nicola Bellizzi for assistance in the bioassay; to Dr. Quanguo Liu for performing Western blots; and to Tonino Piermattei, Ferdinando Costa, Patrizia Cocco, and Daniela Diamanti for their assistance with autoclave tests. We also thank Jeannette Miller and Kang Cai of the Bayer Corporation (Research Triangle Park, NC) for performing Western blot tests of duplicate samples. This work has been partially supported by the Ministero della Salute, Italy, Progetto Finalizzato 1% 2002/3ABF.

Abbreviations

- TSE

transmissible spongiform encephalopathy

- MRM

mechanically recovered meat

- BSE

bovine spongiform encephalopathy

References

- 1.Zanusso G, Righetti P G, Ferrari S, Terrin L, Farinazzo A, Cardone F, Pocchiari M, Rizzuto N, Monaco S. Electrophoresis. 2002;23:347–355. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200202)23:2<347::AID-ELPS347>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cardone F, Liu Q G, Petraroli R, Ladogana A, D'Alessandro M, Arpino C, Pocchiari M. Brain Res Bull. 1999;49:429–433. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee D C, Stenland C J, Miller J L C, Cai K, Ford E K, Gilligan K J, Hartwell R C, Terry J C, Rubenstein R, Fournel M, Petteway S R., Jr Transfusion. 2001;41:449–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41040449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reed J, Muench H. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hite B H. West Virginia Agric Exp Station Bull. 1899;58:15–35. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Food Technologists. Kinetics of Microbial Inactivation for Alternative Food Processing Technologies. Washington, DC: U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2000. http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/∼comm/ift-toc.html , International Food Technology Report, http://vm.cfsan.fda.gov/∼comm/ift-toc.html. . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knorr D. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:485–491. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradley D W, Hess R A, Tao F, Sciaba-Lentz L, Remaley A T, Laugharn J A, Jr, Manak M. Transfusion. 2000;40:193–200. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2000.40020193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer R S, Cooper K L, Knorr D, Lelieveld H L M. Food Technol. 2000;54:67–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor D M. J Hosp Infect. 1999;43,(Suppl.):S69–S76. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(99)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown P, Rau E H, Johnson B K, Bacote A E, Gibbs C J, Jr, Gajdusek D C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3418–3421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050566797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scientific Steering Committee of the European Commission for Food Safety. Update of the Opinion on TSE Infectivity Distribution in Ruminant Tissues. Brussels: Scientific Steering Committee of the European Commission for Food Safety; 2002. http://europa.eu.int/comm/food/fs/sc/ssc/out296_en.pdf , http://europa.eu.int/comm/food/fs/sc/ssc/out296_en.pdf. . [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimberlin R H, Walker C A. Virus Res. 1989;12:213–220. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(89)90040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perrett S, Zhou J-M. Biochim Biophys Acta Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 2002;1595:210–223. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randolph T W, Seefeldt M, Carpenter J F. Biochim Biophys Acta Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 2002;1595:224–234. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrão-Gonzales A D, Souto S O, Silva J L, Foguel D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6445–6450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubois J, Ismail A A, Chan S L, Ali-Khan Z. Scand J Immunol. 1999;49:376–380. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1999.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou J-M, Zhu L, Balny C, Perrett S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:147–152. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Messens W, Van Camp J, Huyghebaert A. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1997;8:107–112. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balny C, Mozhaev V V, Lange R. Comp Biochem A Physiol. 1997;116:299–304. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boonyaratanakornkit B B, Park C B, Clark D S. Biochim Biophys Acta Protein Struct Mol Enzymol. 2002;1595:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(01)00347-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]