Abstract

The antimicrobial activity of the human RNase A superfamily member RNase 8 was evaluated. Recombinant RNase 8 exhibited broad-spectrum microbicidal activity against potential pathogenic microorganisms (including multidrug-resistant strains) at micro- to nanomolar concentrations. Thus, RNase 8 was identified as a novel antimicrobial protein and may contribute to host defense.

Antimicrobial proteins comprise various groups of small gene-encoded endogenous proteins exhibiting a broad spectrum of microbicidal activity against bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Antimicrobial proteins offer a fast response against invading potentially pathogenic microorganisms, thus playing an important role in innate immunity. The widespread occurrence of antimicrobial proteins in the plant and animal kingdoms reflects the significance of these evolutionarily ancient host defense molecules (13). In addition, humans produce various classes of antimicrobial proteins such as alpha- and beta-defensins (4), the cathelicidin LL-37 (12), histatins (8), lysozyme (3), and dermcidin (11).

Another class of human antimicrobial proteins are represented by members of the RNase A superfamily, among them ECP (eosinophil cationic protein/RNase 3), EDN (eosinophil-derived neurotoxin/RNase 2), angiogenin (RNase 5), and RNase 7 (6, 7, 9, 14). Recently, a novel member of the RNase A superfamiliy, termed RNase 8, has been discovered by searching the human genome databases (15). Interestingly, RNase 8 and RNase 7 have an amino acid sequence similarity of 78% and a genomic distance of only 15,000 bp, suggesting that their genes may have evolved from a common ancestor gene by a duplication event (15). RNase 7 exhibits potent antimicrobial activity against gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (6, 14). Although one study reported no antimicrobial activity of a recombinant RNase 8 fusion protein against Escherichia coli (15), the high similarity of RNase 8 to the antimicrobially active RNase 7 suggests that RNase 8 might also act as an antimicrobial protein.

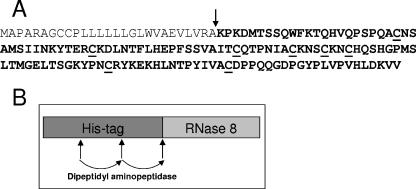

To investigate this hypothesis, we generated recombinant RNase 8 in E. coli. We used the program SignalP 3.0 (1) to determine the putative cleavage site in the RNase 8 amino acid sequence to generate the mature protein (Fig. 1A). The corresponding DNA encoding RNase 8 was amplified from genomic DNA (Promega, Mannheim, Germany) using the forward primer 5′-ACTGCATATGAAGCCCAAGGACATGACATCA-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ATTTGCGGCCGCTTAGACAACTTTATCCAAGTGCA-3′. The resulting fragment was cloned into the expression vector pQE-2 (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) to generate a fusion protein containing an N-terminal His tag sequence allowing purification of the fusion protein by the use of a nickel affinity column (Fig. 1B). After expression of the fusion protein in E. coli BL21(DE3)pLysS (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) the protein was purified using a nickel affinity column (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany), followed by C8 reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) as described previously for the purification of human beta-defensin-3 (5). The N-terminal part of the purified fusion protein was cleaved off by dipeptidyl aminopeptidase I (QIAGEN), and the resulting mature RNase 8 protein was purified by C2/C18 reversed-phase HPLC as previously described (5). Mass analysis using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (QTOF-II hybrid mass spectrometer; Micromass, Manchester, United Kingdom) yielded a mass of 14,201.4 Da, which is 8 Da less than the theoretical mass calculated from the deduced amino acid sequence (14,209.3 kDa), suggesting that the eight cysteyl residues of RNase 8 are connected through four disulfide bridges.

FIG. 1.

Recombinant generation of RNase 8 in E. coli. (A) Amino acid sequence of RNase 8 (single-letter code). Processing at the indicated putative cleavage site (arrow) leads to the mature RNase 8 sequence (boldface letters), which was recombinantly expressed in E. coli. The cysteyl residues presumably involved in disulfide bridges are underlined. (B) Strategy for expression of RNase 8 in E. coli. RNase 8 was expressed as a fusion protein containing an N-terminal His tag sequence. Cleavage of the expressed fusion protein with dipeptidyl aminopeptidase I results in the mature RNase 8 protein.

To test the antimicrobial activity of RNase 8, a panel of reference and clinical isolates of different bacteria and fungi were analyzed in a microdilution assay system (10). Test isolates were grown for 2 to 3 h in brain heart infusion broth at 37°C, washed three times in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and adjusted to 104 to 105 microorganisms/ml. A 100-μl volume of the microbial suspension was mixed with 10 μl of RNase 8 dissolved in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and incubated at 37°C (range of final RNase 8 concentrations tested, 0.001 to 7 μM). After 2 h, the antimicrobial activity of RNase 8 was analyzed by plating serial dilutions of the incubation mixture and determining the CFU the following day. Results are given either as minimal bactericidal concentration (≥99.9% killing) or as the concentration necessary to kill 90% of the microorganisms (90% lethal dose [LD90]).

RNase 8 exhibited a broad spectrum of potent antimicrobial activity against various bacterial strains tested. Many tested strains of gram-positive cocci, gram-negative fermentative rods, and gram-negative nonfermentative rods were shown to be highly susceptible (Table 1). In particular, many pathogenic bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecium, Enterococcus faecalis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae were killed by small amounts of RNase 8 (LD90 = 0.1 to 0.4 μM). Also the yeast Candida albicans was efficiently killed by RNase 8 (LD90 = 0.2 μM). To directly compare the antimicrobial activity of RNase 8 with the activity of RNase 7, we tested natural RNase 7 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 10145) and Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 12600). An LD90 value of 0.1 μM for both Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus indicates a slightly higher activity of RNase 7 compared to RNase 8.

TABLE 1.

Antimicrobial activity of RNase 8 against various clinically relevant microorganisms

| Straina | MBCb (μM) | LD90 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive strains | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 12600 | 1.8 | 0.4 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 33593 (MRSA) | 1.8 | 0.4 |

| Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 43300 (MRSA) | 0.9 | 0.2-0.4 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 14990 | 0.9-1.8 | 0.4-0.9 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 12344 | 0.9-3.5 | 0.2-0.4 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 33400 | >7.0 | 3.5-7.0 |

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 29212 | 0.4-1.8 | 0.2 |

| Enterococcus faecalis ATCC 51299 (VRE) | 3.5 | 0.2-0.4 |

| Enterococcus faecium DSM 2146 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Enterococcus faecium clinical isolate (VRE) | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Enterococcus faecium clinical isolate (VRE) | >7.0 | 0.2 |

| Enterococcus faecium clinical isolate | 0.4 | 0.2-0.4 |

| Gram-negative strains | ||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 | 0.2-0.9 | 0.1-0.2 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 35218 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Escherichia coli ATCC 11775 | 0.4 | 0.1-0.4 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13882 | 0.2-0.9 | 0.1-0.4 |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 | 0.1-0.2 | 0.1 |

| Enterobacter cloacae ATCC 13047 | 7.0 | 0.4 |

| Serratia marcescens NCTC 10211 | >7.0 | >7.0 |

| Citrobacter freundii NCTC 9750 | >7.0 | 0.4-3.5 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 10145 | 0.4-0.9 | 0.2-0.4 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Pseudomonas fluorescens NCTC 10038 | >7.0 | 0.9-1.8 |

| Burkholderia cepacia ATCC 25416 | >7.0 | >7.0 |

| Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 | 0.2 | 0.1 |

| Fungus, Candida albicans ATCC 24433 | 1.8 | 0.2 |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

MBC, minimal bactericidal concentration.

The high activity of RNase 8 indicates that this antimicrobial protein could contribute to innate immunity and may help to protect the body from infection. Using Northern blot analysis Zhang and colleagues screened various tissues for RNase 8 gene expression and detected RNase 8 gene expression only in the placenta (15). This suggests that RNase 8 may play a role in protecting the placenta from infection.

The signal sequence of RNase 8 (Fig. 1A) displays a high similarity with the signal sequence of RNase 7 (85% identity). Since RNase 7 is secreted by epithelial cells (6; our unpublished data), one can speculate that RNase 8 may also be secreted. However, this remains to be proven.

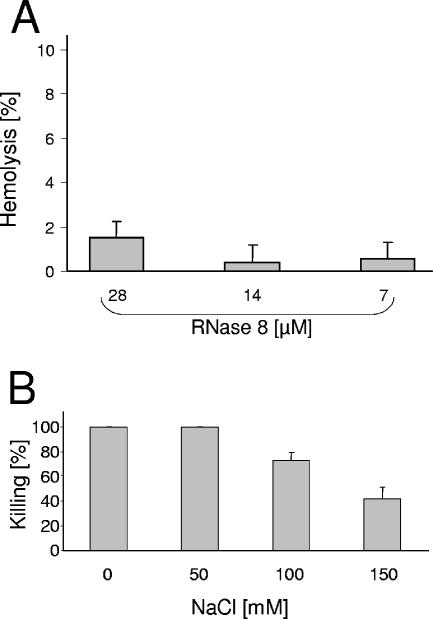

Since several antimicrobial proteins have been reported to exhibit cytotoxic activity against eukaryotic cells, RNase 8 was also assayed for hemolytic activity against human erythrocytes as previously described (5). Little hemolytic activity was observed after incubation of erythrocytes with up to 28 μM RNase 8 (Fig. 2A). These data indicate that the killing activity of RNase 8 is specific for microorganisms and does not affect human cells.

FIG. 2.

Hemolytic activity and salt sensitivity of RNase 8. (A) For analysis of hemolytic activity RNase 8 was incubated at 37°C for 3 h with 1 × 109 human erythrocytes/ml in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 0.34 M sucrose. Hemolysis was determined by measuring the A450 of the supernatants using 0.1% Triton X-100 for 100% hemolysis. (B) To test the salt sensitivity of RNase 8, E. coli (ATCC 35218) was treated with 3.5 μM RNase 8 in the presence of various concentrations of NaCl.

The activity of many antimicrobial proteins is inhibited by increased salt concentrations. Here we show that RNase 8 is still active in the presence of 100 mM NaCl but exhibits reduced antimicrobial activity in the presence of 150 mM NaCl, indicating that increased salt concentrations affect the antimicrobial activity of RNase 8 (Fig. 2B). Recently, it has been shown that carbonate confers on cathelicidins such as LL-37 the ability to kill at high salt concentrations (2). We found that addition of 50 mM carbonate did not reduce the salt sensitivity of RNase 8 (not shown). A major goal of future research should be to identify and analyze the cellular sources of RNase 8, its local concentrations, and the characteristics of its physiological environmental conditions (i.e., ion and protein composition, pH, and bacterial physiology). This would provide more insight into the role of RNase 8 in host defense.

As mentioned above Zhang and colleagues recently reported that RNase 8 exhibits no antibacterial activity (15), an observation that is at variance with our results reported here. However, in contrast to our study Zhang et al. examined antibacterial activity against E. coli by measuring the growth of E. coli that expressed a recombinant RNase 8-FLAG fusion protein (15). These methodological differences may most likely account for the different results of these studies.

In summary, our data suggest that RNase 8 could contribute to innate immunity by acting as a potent antimicrobial protein. The broad-spectrum activity of RNase 8 also against multiresistant strains indicates that RNase 8 may be a useful agent for treating infections caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB 617).

We thank C. Butzeck-Mehrens, J. Quitzau, K. Schultz, and S. Voss for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bendtsen, J. D., H. Nielsen, G. von Heijne, and S. Brunak. 2004. Improved prediction of signal peptides: SignalP 3.0. J. Mol. Biol. 340:783-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorschner, R. A., B. Lopez-Garcia, A. Peschel, D. Kraus, K. Morikawa, V. Nizet, and R. L. Gallo. 2006. The mammalian ionic environment dictates microbial susceptibility to antimicrobial defense peptides. FASEB J. 20:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ganz, T. 2004. Antimicrobial polypeptides. J. Leukoc. Biol. 75:34-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ganz, T. 2003. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:710-720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harder, J., J. Bartels, E. Christophers, and J. M. Schröder. 2001. Isolation and characterization of human beta-defensin-3, a novel human inducible peptide antibiotic. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5707-5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harder, J., and J. M. Schröder. 2002. RNase 7, a novel innate immune defense antimicrobial protein of healthy human skin. J. Biol. Chem. 277:46779-46784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hooper, L. V., T. S. Stappenbeck, C. V. Hong, and J. I. Gordon. 2003. Angiogenins: a new class of microbicidal proteins involved in innate immunity. Nat. Immunol. 4:269-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kavanagh, K., and S. Dowd. 2004. Histatins: antimicrobial peptides with therapeutic potential. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 56:285-289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenberg, H. F. 1998. The eosinophil ribonucleases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 54:795-803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahly, H., S. Schubert, J. Harder, P. Rautenberg, U. Ullmann, J. Schröder, and R. Podschun. 2003. Burkholderia is highly resistant to human beta-defensin 3. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1739-1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schittek, B., R. Hipfel, B. Sauer, J. Bauer, H. Kalbacher, S. Stevanovic, M. Schirle, K. Schroeder, N. Blin, F. Meier, G. Rassner, and C. Garbe. 2001. Dermcidin: a novel human antibiotic peptide secreted by sweat glands. Nat. Immunol. 2:1133-1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zanetti, M. 2005. The role of cathelicidins in the innate host defenses of mammals. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 7:179-196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zasloff, M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang, J., K. D. Dyer, and H. F. Rosenberg. 2003. Human RNase 7: a new cationic ribonuclease of the RNase A superfamily. Nucleic Acids Res. 31:602-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang, J., K. D. Dyer, and H. F. Rosenberg. 2002. RNase 8, a novel RNase A superfamily ribonuclease expressed uniquely in placenta. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:1169-1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]