Abstract

Candida albicans is a commensal fungus of mucosal surfaces that can cause disease in susceptible hosts. One aspect of the success of C. albicans as both a commensal and a pathogen is its ability to adapt to diverse environmental conditions, including dramatic variations in environmental pH. The response to a neutral-to-alkaline pH change is controlled by the Rim101 signal transduction pathway. In neutral-to-alkaline environments, the zinc finger transcription factor Rim101 is activated by the proteolytic removal of an inhibitory C-terminal domain. Upon activation, Rim101 acts to induce alkaline response gene expression and repress acidic response gene expression. Previously, recombinant Rim101 was shown to directly bind to the alkaline-pH-induced gene PHR1. Here, we demonstrate that endogenous Rim101 also directly binds to the alkaline-pH-repressed gene PHR2. Furthermore, we find that of the three putative binding sites, only the −124 site and, to a lesser extent, the −51 site play a role in vivo. In C. albicans, the predicted Rim101 binding site was thought to be CCAAGAA, divergent from the GCCAAG site defined in Aspergillus nidulans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Our results suggest that the Rim101 binding site in C. albicans is GCCAAGAA, but slight variations are tolerated in a context-dependent fashion. Finally, our data suggest that Rim101 activity is governed not only by proteolytic processing but also by an additional mechanism not previously described.

The ability of microbes to sense and respond to changes in environmental pH is critical for their survival. The Rim101/PacC signal transduction pathway is required for adaptation to neutral-to-alkaline environments in fungi. This pathway is found throughout both yeast and molds of the ascomycota and has recently been identified in the basidiomycota (2, 6, 25). The Rim101/PacC pathway is also important for pathogenesis in both animal and plant pathogens (5, 7). Thus, the ability to respond to environmental pH is linked to the ability of fungi to cause disease.

The conserved Rim101/PacC pathway governs changes in gene expression through the zinc finger transcription factor Rim101/PacC, which is itself regulated by proteolytic processing. At an acidic pH, Rim101/PacC is found in either a full-length (unprocessed) form or a processed form thought to be inactive; at alkaline pH, Rim101/PacC is found in a processed form that is capable of promoting changes in gene expression (6, 19, 25, 33). Proteolytic processing is controlled by a number of upstream members of the pathway including Rim8/PalF, Rim13/PalB, Rim20/PalA, Rim21/PalH, and Snf7 (6, 8, 10, 15, 16, 19, 20, 26, 33, 34). Furthermore, many members of the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complex required for transport) machinery, which includes Snf7, are required for Rim101 processing (34). In total, these factors act to promote Rim101/PacC processing and adaptation to neutral-to-alkaline environments.

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Rim101 appears to act primarily as a repressor of pH-dependent gene expression. In this system, Rim101-dependent induction of targets, such as ENA1, is indirect (17, 18). Rim101 represses the expression of additional transcriptional repressors, such as Nrg1, which is a repressor of ENA1 expression. In fact, all of the Rim101 activity in S. cerevisiae can be attributed to its ability to repress transcription (17). In Aspergillus nidulans, PacC appears to directly act as both a repressor and an inducer of pH-dependent gene expression (11, 25, 29).

In Candida albicans, Rim101 acts as a repressor of genes expressed preferentially at acidic pH compared to alkaline pH and as an inducer of genes expressed preferentially at alkaline pH compared to acidic pH (4, 8, 26, 28). However, its role as an inducer is more clearly defined. For example, Rim101 is required for the induction of PHR1 at a neutral-to-alkaline pH (8, 28). Ramon and Fonzi previously demonstrated that a recombinant Rim101 DNA binding domain-glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion binds directly to the PHR1 promoter. Furthermore, those authors showed that this binding is required for alkaline-pH-dependent induction of PHR1 (27). In A. nidulans and S. cerevisiae, PacC/Rim101 binds with high affinity to the 5′-GCCAAG sequence (17, 27, 29). However, the C. albicans PHR1 promoter does not contain a 5′-GCCAAG sequence. Interestingly, Ramon and Fonzi found that C. albicans Rim101 binds to the divergent 5′-CCAAGAA sequence. Thus, C. albicans Rim101 can act directly as an inducer of gene expression by binding to a divergent Rim101/PacC binding site.

However, C. albicans Rim101 may not be specific for the divergent 5′-CCAAGAA sequence. We identified 186 alkaline-pH-induced and Rim101-dependent genes by transcriptional profiling (4). Analysis of alkaline-pH- and Rim101-dependent promoters revealed the 5′-GCCAAGAA site as a conserved motif. This site contains both the classical 5′-GCCAAG and divergent 5′-CCAAGAA Rim101 binding sites. Thus, C. albicans Rim101 may in fact bind to a classical site motif.

While Rim101 clearly acts as an inducer in C. albicans, it is not known if it can directly act as a repressor. Rim101 binding sites can be found in the promoters of some genes repressed at alkaline pH in a Rim101-dependent manner, but analysis of the 20 most alkaline-pH-repressed Rim101-dependent promoters using the MEME algorithm did not identify a Rim101 binding site. Furthermore, in the absence of Rim101, all analyzed alkaline-pH-repressed Rim101-dependent genes became alkaline induced (4, 8). This suggests that an additional factor(s) may regulate these genes. Thus, Rim101 may indirectly govern alkaline-pH-repressed gene expression through this other factor. This situation would mirror that in S. cerevisiae, where Rim101 indirectly acts as an inducer by repression of another transcriptional repressor (17).

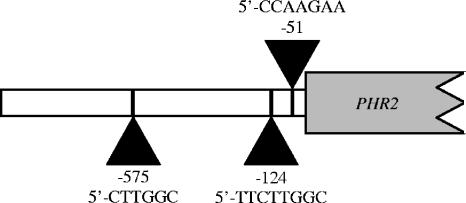

Here, we studied the role of C. albicans Rim101 in the repression of the PHR2 gene. PHR2 encodes a functional homolog of the Phr1 cell wall β-glycosidase and is expressed in a pH- and Rim101-dependent manner (14, 23). However, unlike PHR1, PHR2 is expressed preferentially at acidic pH and is repressed at alkaline pH in a Rim101-dependent manner (8, 23). Sequence analysis of a 1,000-bp region of the PHR2 promoter upstream of ATG identified three potential Rim101 binding sites at positions −575, −124, and −51, suggesting that PHR2 may be directly regulated by Rim101 (Fig. 1). While all three sites are potential Rim101 binding sites, the −575 and −124 sites are in the opposite orientation. Furthermore, the −575 site specifies a classical consensus sequence, 5′-CTTGGC; the −124 site can specify both a classical and a divergent consensus sequence, 5′-TTCTTGGC; and the −51 site specifies only the divergent consensus sequence 5′-CCAAGAA. Through electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) and LacZ reporter analyses, we found that specific Rim101 binding sites within the PHR2 promoter are important for Rim101-dependent repression at alkaline pH. Furthermore, we found that endogenous Rim101 binds to these sites in vitro and that binding does not require Rim101 processing. Thus, our studies demonstrate that Rim101 acts directly as a repressor of transcription in C. albicans. Finally, our results suggest that Rim101 binding activity is governed by an additional mechanism independent of proteolytic processing.

FIG. 1.

Diagram of the putative Rim101 binding sites within the PHR2 promoter. The sites at positions −575 and −124 are in the opposite orientation to the start codon. All three sequences are listed from the sense strand.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

All strains used in these studies are listed in Table 1 and have been previously described.

TABLE 1.

Strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| DAY1 (BWP17) | ura3Δ::λimm434his1::hisGarg4::hisG | 32 |

| ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG arg4::hisG | ||

| DAY5 | ura3Δ::λimm434his1::hisGarg4::hisGrim101::URA3 | 32 |

| ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG arg4::hisG rim101::ARG4 | ||

| DAY286 | ura3Δ::λimm434his1::hisGpARG4::URA3::arg4::hisG | 9 |

| ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG arg4::hisG | ||

| DAY432 | ura3Δ::λimm434his1::hisGarg4::hisGrim101::dpl200 | 31 |

| ura3Δ::λimm434 his1::hisG arg4::hisG rim101::dpl200 | ||

| DAY492 | ura3Δ::λimm434arg4::hisGrim101::ARG4pHIS1::RIM101-V5-AgeI::his1::hisG | 19 |

| ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG rim101::URA3 his1::hisG | ||

| DAY643 | ura3Δ::λimm434arg4::hisGrim13::URA3pHIS1::RIM101-V5-AgeI::his1::hisG | 19 |

| ura3Δ::λimm434 arg4::hisG rim13::ARG4 his1::hisG |

Genotypes are shown as the two alleles of a given locus.

The PPHR2-driven lacZ construct pDDB225 was generated as follows. LacZ from Streptococcus thermophilus was amplified from pAU36 in a PCR (30) by using primers St. LacZ fus5′ and Mlu-Not-ACT1 UTR (Table 2). The resulting PCR product was ligated into pGEM-T Easy (Promega) to generate pDDB211. A total of 998 bp of the PHR2 promoter was amplified in a PCR using primers PHR2-1005 and PHR2-ATG, and the resulting PCR product was ligated into pGEM-T Easy to generate pDDB213. pDDB211 was digested with AseI/MluI and ligated into NdeI/MluI-digested pDDB213 to generate pDDB218. The PPHR2-lacZ construct was removed from pDDB218 by SapI/NgoMIV digestion and transformed into a trp1− S. cerevisiae strain with NotI/EcoRI-digested pDDB78 to generate pDDB225 by in vivo recombination (22).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| 3′ detect | tgtggaattgtgagcggataacaatttcac |

| 5′SnaBICaHis1 | gtagtggaagatattctttattgaaaaatagcttgtcaccggatcctggaggatgaggag |

| St. LacZ fus5′ | attaatgaacatgactgaaaaaattc |

| Mlu-Not-ACT1 UTR | acgcgtgcggccgctttacaatcaaaggtggtcc |

| LacZ+354c | acagcatttgattcttgagg |

| PHR2 ATG | catatggatcgaatgtgtgt |

| PHR2-1005 | cgtcgtgtggatcgagtggc |

| Pphr2-48m1 | gtttagtactttccttctagCCggcAAttcaaggaatcatcgtc |

| Pphr2-48m2 | gacgatgattccttgaaTTgccGGctagaaggaaagtactaaac |

| Pphr2-117m1 | cttttttttttcttgTTgccGGCtttcctccccttaactgg |

| Pphr2-117m2 | ccagttaaggggaggaaaGCCggcAAcaagaaaaaaaaaag |

| Pphr2-569m1 | gaaggaaaaaaaatatttcgccGGCttaaacatcgctggcgttg |

| Pphr2-569m2 | caacgccagcgatgtttaaGCCccggaaatattttttttccttc |

| PPHR2-117 aCCAAGA 5′ | ttcttcatctttcttttttttttcttgttTCTTGGttttcctccccttaactggttttttttct |

| PPHR2-117 aCCAAGA 3′ | agaaaaaaaaccagttaaggggaggaaaaCCAAGAaacaagaaaaaaaaaagaaagatgaagaa |

| PPHR2-117 GCCAAGg 5′ | ttcttcatctttcttttttttttcttgttcCTTGGCtttcctccccttaactggttttttttct |

| PPHR2-117 GCCAAGg 3′ | agaaaaaaaaccagttaaggggaggaaaGCCAAGgaacaagaaaaaaaaaagaaagatgaagaa |

| PPHE2-117 aCCAAGA 5′EMSA | ttttttttcttgttTCTTGGttttcctccccttaa |

| PPHE2-117 aCCAAGA 3′EMSA | ttaaggggaggaaaaCCAAGAaacaagaaaaaaaa |

| PPHR2-117 GCCAAGg 5′EMSA | ttttttttcttgttcCTTGGCtttcctccccttaa |

| PPHR2-117 GCCAAGg 3′EMSA | ttaaggggaggaaaGCCAAGgaacaagaaaaaaaa |

| BS-825sh | aaaaaaaaaCCAAGAAaaatattccatctttata |

| BS-825shc | tataaagatggaatatttTTCTTGGttttttttt |

| BS-825Xsh | aaaaaaaaatCtAGAAaaatattccatctttata |

| BS-825Xshc | tataaagatggaatatttTTCTaGattttttttt |

| PHR2-48 5a′ | agtactttccttctaCCAAGAAattcaaggaatca |

| PHR2-48 3a′ | tgattccttgaatTTCTTGGtagaaggaaagtact |

| PHR2-48mut 5a′ | agtactttccttctgCCggcAaattcaaggaatca |

| PHR2-48mut 3a′ | tgattccttgaattTgccGGcagaaggaaagtact |

| PHR2-117 5a′ | ttttttttcttgtTTCTTGGCtttcctccccttaa |

| PHR2-117 3a′ | ttaaggggaggaaaGCCAAGAAacaagaaaaaaaa |

| PHR2-117mut 5a′ | ttttttttcttgtTTgccGGCtttcctccccttaa |

| PHR2-117mut 3a′ | ttaaggggaggaaaGCCggcAAacaagaaaaaaaa |

| PHR2-569 5′ | gaaaaaaaatatttcCTTGGCttaaacatcgctgg |

| PHR2-569 3′ | ccagcgatgtttaaGCCAAGgaaatattttttttc |

| PHR2-569mut 5′ | gaaaaaaaatatttcgccGGCttaaacatcgctgg |

| PHR2-569mut 3′ | ccagcgatgtttaaGCCggcgaaatattttttttc |

Rim101 binding sites are in capital letters, and mutations are underlined.

The −51 site-specific mutation within PPHR2 was derived from pDDB213 using primers PHR2-48mut 5a′ and PHR2-48 mut 3a′ using the GeneEditor system (Promega) to generate pDDB251. Next, pDDB211 was digested with AseI/MluI and ligated into NdeI/MluI-digested pDDB251 to generate pDDB252. The PPHR2-51-lacZ construct was removed from pDDB252 by SapI/NgoMIV digestion and introduced into pDDB78 by in vivo recombination to yield pDDB254.

The −124 and −575 site-specific mutations were generated as follows. PPHR2-lacZ was amplified in two fragments from pDDB225 using primers Pphr2-117m1b (or Pphr2-569m1) with 3′-detect and Pphr2-117m2b (or Pphr2-569m2) with 5′SnaBICaHis1. These two fragments were introduced into NheI/ClaI-digested pDDB225 by in vivo recombination, resulting in pDDB255 for −124 site-specific mutation and pDDB256 for −575 site-specific mutation.

The double mutations at positions −51 and −124, −51 and −575, and −124 and −575 were generated by the same strategy used for the −124 and −575 site-specific mutations with the same primers using NheI/ClaI-digested pDDB254 for the double mutations at positions −51 and −124 and −51 and −575 and pDDB333 for the double mutations at positions −124 and −575 to yield pDDB334, pDDB335, and pDDB336, respectively, after in vivo recombination. The triple mutation at positions −51, −124, and −575 was generated using NheI/ClaI-digested pDDB335 to yield pDDB337.

The −124 point mutations for the classical and divergent Rim101 binding consensus sequences (GCCAAGAA) were generated by in vivo recombination between two amplified PPHR2-lacZ fragments using primers Pphr2-117 aCCAAGA 5′ (or Pphr2-117 GCCAAGg-5′) with 3′-detect and Pphr2-117 aCCAAGA 3′ (or Pphr2-117 GCCAAGg-3′) with 5′SnaBICaHis1 and NheI/ClaI-digested pDDB225 to yield pDDB338 and pDDB339, respectively.

Plasmids pDDB225, pDDB254, and pDDB332 through pDDB339 were digested with NruI and transformed into DAY1 and DAY432 to generate strains for β-galactosidase assays. Correct integration was verified by PCR with the primers PHR2-1005 and LacZ + 354c. The PHR2 promoter region of all plasmid constructs was confirmed by sequencing.

Media and growth conditions.

C. albicans was routinely grown in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose plus uridine (2% Bacto peptone, 1% yeast extract, 2% dextrose, and 80 μg of uridine per ml). Selection for the His+ transformants was done on synthetic medium (0.67% yeast nitrogen base plus ammonium sulfate and without amino acids, 2% dextrose, and 80 μg of uridine per ml supplemented with the required auxotrophic needs of the cells).

β-Galactosidase assays.

For liquid β-galactosidase assays, cell pellets grown to mid-log phase in 35 ml of pH 4 or pH 8 M199 medium with 150 mM HEPES were resuspended in 1 ml Z buffer (1). Each cell suspension was diluted 20-fold to determine the optical density at 600 nm. One hundred fifty microliters of cell suspension was then added to a mixture of 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and chloroform for permeabilization. After a 10-min incubation at 37°C, 0.7 ml ONPG (o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside) (1 mg/ml) was added for the β-galactosidase reaction. Reactions were terminated by adding 0.5 ml 1 M Na2CO3 when the solution turned yellow, and the A420 was determined. Miller units were calculated as follows: A420/(optical density at 600 nm × volume assayed × time) (1). Data were analyzed by analysis of variance to determine statistical relationships.

Protein preparation.

Cultures were grown to saturation overnight in yeast extract-peptone-dextrose plus uridine. Cells were diluted 40-fold into M199 medium buffered with 150 mM HEPES to pH 4 or pH 8 and grown for 4 h at 30°C. Cells were pelleted and stored at −80°C prior to protein extraction. Cell pellets were resuspended in ice-cold radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml pepstatin, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 10 mM dithiothreitol and transferred into glass test tubes containing acid-washed glass beads. Cells were lysed by vortexing four times for 2 min, followed by 2 min on ice. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and supernatants were removed and stored at −80°C.

Western blot analyses.

For Western blots, 20 μl of 2× SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) sample buffer was added to 20 μl supernatant, and samples were boiled for 5 min. Samples were loaded onto an 8% SDS-PAGE gel and run overnight at 35 V. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose and blocked. Anti-V5-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) antibody (Invitrogen) in 30 ml 5% nonfat milk-Tris-buffered saline-Tween solution (1:7,500 dilution) was added to the blot for 4 h at 4°C. Blots were washed in Tris-buffered saline-Tween, incubated with ECL reagent (Amersham Biosciences), and exposed to film. Blots were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH).

EMSA.

EMSAs were performed as follows. Forty femtomoles of DNA probe was incubated with 20 μg of cell extract in 20 μl of binding buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 4% glycerol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 50 mM NaCl, 2 μg of poly(dI-dC)] at room temperature for 30 min. DNA-protein complexes were resolved on 4% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gels in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer at room temperature overnight. After electrophoresis, the gels were dried and visualized with a phosphorimager. For supershift assays, 20 μg of cell extract was incubated with 1 μg of anti-V5-HRP antibody on ice for 30 min prior to the addition of the DNA probe, and the binding reaction was allowed to proceed for an additional 30 min at room temperature. All DNA probes were end labeled by T4 polynucleotide kinase with [γ-32P]dATP. EMSAs were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH).

RESULTS

Rim101 can bind to all three Rim101 binding sites within the PHR2 promoter.

Previous studies demonstrated that PHR2 expression is pH and Rim101 dependent (8). We predicted that this regulation was due to Rim101 binding sites within the PHR2 promoter. To biochemically test this possibility, we conducted ESMAs using C. albicans whole-cell protein extracts. Previous studies demonstrated that a recombinant Rim101 DNA binding domain-GST fusion bound to the PHR1 promoter by EMSA (27). Thus, we first assessed the binding of endogenous Rim101 to the PHR1 promoter. Radiolabeled DNA probes were generated by annealing the PHR1 oligomers BS-825sh and BS-825shc (27) and end labeling. The resulting probes were incubated with protein extracts from wild-type cells, separated by nondenaturing PAGE, and analyzed on a phosphorimager. EMSA of these probes incubated with protein extracts from wild-type cells revealed two distinct gel shift bands compared to free probe (noted as A and B in Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 2). Radiolabeled DNA probes were next generated using oligomers BS-825Xsh and BS-825Xshc (27), which contain a mutated Rim101 binding site, and incubated with protein extracts from wild-type cells. EMSA of these mutated probes revealed a gel shift to band A but not to band B (Fig. 2, lane 3). Similar results were obtained using radiolabeled DNA probes from oligomers BS-825sh and BS-825shc and protein extracts from rim101−/− cells (Fig. 2, lane 4). These results extend the results described previously by Ramon and Fonzi (27) and suggest that endogenous Rim101 binds to the divergent sequence 5′-CCAAGAA of the PHR1 promoter.

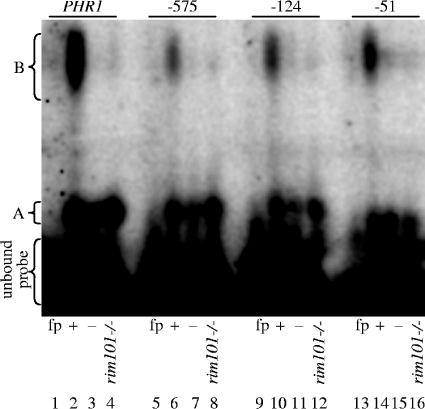

FIG. 2.

EMSA of promoter regions containing putative Rim101 binding sites. Protein extracts from wild-type (DAY286) (lanes 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, and 15) and rim101−/− (DAY5) (lanes 4, 8, 12, and 16) strains grown at pH 8 were incubated with radiolabeled DNA probes for endogenous (+) (lanes 2 and 4) or mutated (−) (lane 3) PHR1 oligomers or endogenous (+) (lanes 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16) or mutated (−) (lanes 7, 11, and 15) PHR2 (−575, −124, and −51) oligomers and analyzed by EMSA. Lanes 1, 5, 9, and 13 contain free probe (fp) without protein extracts.

We next determined whether each of the putative Rim101 binding sites within the PHR2 promoter can interact with Rim101. Radiolabeled 35-bp DNA probes that span the −575, −124, or −51 putative Rim101 binding site were generated by annealing probes PHR2-569 5′ and PHR2-569 3′, PHR2-117 5′ and PHR2-117 3′, or PHR2-48 5′ and PHR2-48 5′, respectively, and end labeling. Like the results observed for the PHR1 probe, EMSA of these probes incubated with protein extracts from wild-type cells revealed two distinct gel shift bands (A and B) (Fig. 2, lanes 2, 6, 10, and 14). However, there was less gel shift to band B observed for the PHR2 probes than for the PHR1 probes. These results demonstrate that a protein(s) is able to bind to the PHR2 promoter fragments.

We next asked whether the gel shifts observed with the PHR2 promoter fragments were dependent on the predicted Rim101 binding sites. Oligomers in which the core sequence found in both the classical and divergent Rim101 binding sites was changed from 5′-CCAAG to 5′-CCGGC (change is underlined) were designed. Radiolabeled probes that span the −575, −124, or −51 site and that contain these mutations were generated using oligomers PHR2-569mut 5′ and PHR2-569mut 3′, PHR2-117mut 5′ and PHR2-117mut 3′, and PHR2-48mut 5′ and PHR2-48mut 5′, respectively. EMSA of these mutated probes incubated with protein extracts from wild-type cells revealed a dramatic decrease in the amount of probe shifted to band B but not band A, similar to results seen for the PHR1 binding site (Fig. 2, lanes 3, 7, 11, and 15). Finally, probes derived from oligomer probes PHR2-569 5′ and PHR2-569 3′, PHR2-117 5′ and PHR2-117 3′, and PHR2-48 5′ and PHR2-48 5′ were incubated with protein extracts from rim101−/− cells and analyzed by EMSA (Fig. 2, lanes 4, 8, 12, and 16). Again, a drastic reduction in probe shifted to band B but not band A was observed, supporting the idea that these PHR2 site promoter fragments interact with Rim101 through the Rim101 binding site.

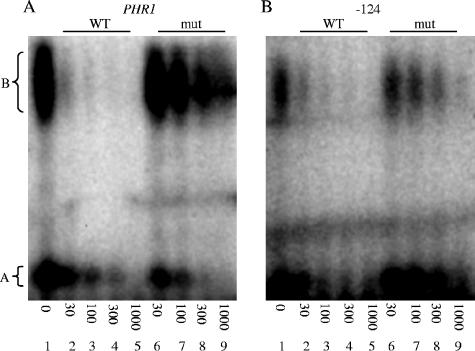

The fact that the mutated PHR1 and PHR2 DNA probes failed to interact with Rim101 strongly suggests that this interaction is specific. To further address this possibility, we conducted competition EMSAs. We first analyzed the ability of cold wild-type PHR1 or mutated PHR1 DNA fragments, generated by annealing the primer pairs described above, to compete for Rim101 binding to a radiolabeled wild-type PHR1 probe (Fig. 3). The addition of 30-fold excess cold wild-type PHR1 DNA fragment effectively abolished most of the Rim101-dependent gel shift (Fig. 3A, lane 2). However, the addition of 1,000-fold excess cold mutated PHR1 DNA fragment was required to reduce the Rim101-dependent gel shift to band B (Fig. 3A, lane 9). We noted that band A was effectively competed with either cold competitor, suggesting that this band is a nonspecific artifact. We next analyzed the ability of cold wild-type −124 and mutated −124 PHR2 DNA fragments, generated as described above, to compete for Rim101 binding to the radiolabeled wild-type −124 probe. The addition of 30-fold excess cold wild-type −124 PHR2 DNA fragment significantly reduced the Rim101-dependent gel shift (Fig. 3B, lane 2). However, the addition of 300-fold excess cold mutated −124 PHR2 DNA fragment was required to similarly reduce the Rim101-dependent gel shift (Fig. 3B, lane 8). These results support the idea that the band B gel shift is due to a specific Rim101-dependent interaction.

FIG. 3.

Competition assays for Rim101-dependent binding to the putative Rim101 binding sites. Protein extracts from wild-type (DAY286) cells grown at pH 8 were incubated with radiolabeled probe for PHR1 (A) or PHR2 −124 (B) in the absence (lane 1) of competitor, in the presence of 30- to 1,000-fold excess wild-type (WT) (lanes 2 to 5) cold competitor, or in the presence of 30- to 1,000-fold excess mutant (mut) (lanes 6 to 9) cold competitor.

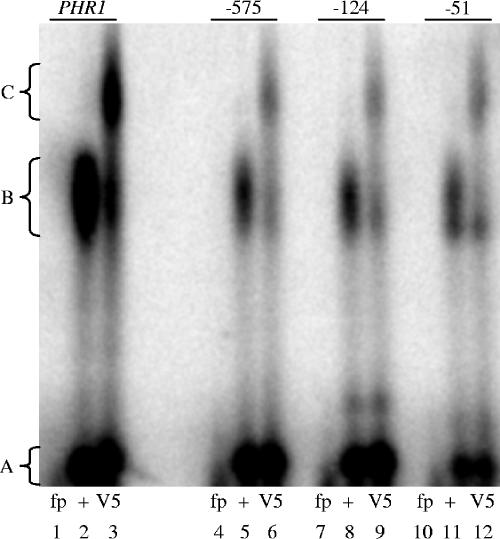

Although these results implicate Rim101 as the factor responsible for the gel shift, it is possible that another factor, which is itself Rim101 dependent, binds to the putative Rim101 binding sites in the PHR2 promoter. To establish whether the gel shifts observed are directly due to Rim101, we conducted EMSAs using extracts from rim101−/− + RIM101-V5 cells, which express only epitope-tagged Rim101-V5 (19). Protein extracts from rim101−/− + RIM101-V5 cells showed gel shift patterns with the PHR1 and PHR2 probes and the mutated PHR2 probes similar to wild-type protein extracts (Fig. 4, lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11 and data not shown). However, protein extracts from rim101−/− + RIM101-V5 cells incubated with an anti-V5-HRP antibody and the PHR1 and PHR2 probes resulted in a supershift C band (Fig. 4, lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12). Concomitant with the presence of the C band, there was a loss of the B band but not the A band. No band C gel shift was observed using protein extracts from a strain carrying the V5 epitope tag within the Snf7 protein, demonstrating that the V5 epitope tag was not conferring DNA binding ability (data not shown). Thus, in total, these results suggest that endogenous Rim101 can interact with all three Rim101 binding sites within the PHR2 promoter.

FIG. 4.

Supershift assays demonstrate that Rim101 binds to promoter regions containing the Rim101 binding site. Protein extracts from rim101−/− + RIM101-V5 (DAY492) cells grown at pH 8 incubated with anti-V5-HRP antibody (V5) (lanes 3, 6, 9, and 12) or without anti-V5-HRP antibody (+) (lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11) were allowed to bind to DNA probes for wild-type PHR1 or PHR2 (−575, −124, and −51) promoters. Lanes 1, 4, 7, and 10 contain free probe (fp) without protein extract.

The −124 binding site is the most important site in vivo.

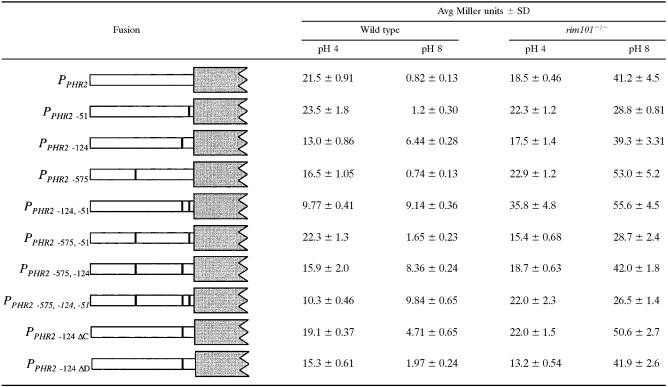

Rim101 appears to bind to all three putative binding sites within the PHR2 promoter in vitro. However, these assays contain a vast excess of probe as demonstrated by the amount of unbound probe shown in Fig. 2, so it is possible that these interactions are artifacts of the in vitro assay. Thus, we asked whether these sites were important in vivo. In order to address this issue, we constructed a LacZ reporter driven from the PHR2 promoter. The PHR2 promoter region, containing all three putative Rim101 binding sites, was amplified by PCR and cloned next to lacZ from S. thermophilus (30). The resulting PPHR2-lacZ reporter was introduced into plasmid pDDB78 and transformed into wild-type and rim101−/− C. albicans strains (Table 3). In wild-type cells, PPHR2-lacZ was repressed ∼30-fold when cells were grown at pH 8 compared to pH 4. In rim101−/− cells, PPHR2-lacZ expression was similar to that of wild-type cells at pH 4 but was now overexpressed about two- to threefold at pH 8. These results are consistent with Northern blot data, which demonstrated that PHR2 is expressed preferentially at pH 4 compared to pH 8 in wild-type cells and was expressed about threefold more at pH 8 than at pH 4 in rim101−/− cells (8). Thus, the PPHR2-lacZ construct is expressed in a pH- and Rim101-dependent manner.

TABLE 3.

PHR2 promoter LacZ fusions identify the −124 site as the critical Rim101 binding sitea

β-Galactosidase assays were performed on PPHR2-lacZ reporter strains grown at pH 4 and pH 8. At least three independent transformants were used to determine average Miller units and standard deviations.

To determine if the putative Rim101 binding sites confer pH- and/or Rim101-dependent expression, we generated site-specific mutations in each of the three sites and assayed the effect of these mutations on LacZ expression. We first mutated the −51 and the −575 sites, which were changed from 5′-aCCAAGAA to 5′-gCCggcAA and from 5′-CTTGGC to 5′-gccGGC, respectively, and then analyzed LacZ expression at pH 4 and pH 8 (Table 3) (underlining represents mutations compared to the wild-type sequence, capital letters are the Rim101 binding site, and lowercase indicates a mutation or non-Rim101 binding site nucleotide). In wild-type cells at pH 4, PPHR2-575-lacZ was expressed at slightly reduced levels compared to PPHR2-lacZ (P < 0.0015), although no effect was observed for PPHR2-51-lacZ. At pH 8, both PPHR2-51-lacZ and PPHR2-575-lacZ were repressed ∼20-fold, which was not significantly different than that of the wild-type PPHR2-lacZ fusion (P = 0.071 and 0.48, respectively). Thus, the −51 and −575 sites do not have a dramatic effect on PHR2 pH-dependent expression.

We next mutated the −124 site from 5′-TTCTTGGC to 5′-TTgccGGC and analyzed expression. In wild-type cells at pH 4, PPHR2-124-lacZ was expressed at reduced levels compared to PPHR2-lacZ (P < 5 × 10−5), suggesting that bases at the −124 site may play a role in basal transcription. In wild-type cells at pH 8, PPHR2-124-lacZ showed only twofold repression, which is ∼15-fold less repression than that observed for PPHR2-lacZ. This suggests that the −124 site plays a dramatic role in PHR2 pH-dependent expression.

In rim101−/− cells at pH 4, PPHR2-51-lacZ, PPHR2-124-lacZ, and PPHR2-575-lacZ were expressed at levels similar to those observed in wild-type cells. PPHR2-124-lacZ and PPHR2-575-lacZ were overexpressed like PPHR2-lacZ in the rim101−/− background. However, at pH 8, PPHR2-51-lacZ was overexpressed significantly less than PPHR2-lacZ in the rim101−/− background (P < 0.0093). These results suggest that the −51 site, but not the −124 and the −575 sites, may play a role in PHR2 Rim101-independent transcriptional regulation.

The −124 site appears to be the most important site for the pH-dependent repression of PHR2. However, alkaline-pH-dependent repression was still present in the PPHR2-124-lacZ construct. To determine if this residual repression was conferred by the −51 and/or −575 site, we constructed PPHR2-lacZ fusions that contained mutations in two or three of the putative Rim101 binding sites and analyzed expression in wild-type and rim101−/− cells (Table 3).

The PPHR2-124,-575-lacZ construct had no differences in lacZ expression compared to the PPHR2-124-lacZ construct at either pH 4 or pH 8. Furthermore, in the wild-type background, the PPHR2-51,-575-lacZ double-mutant construct was not statistically different from the PPHR2-51-lacZ construct. These results support the idea that the −575 site is not critical for PHR2 pH-dependent regulation. However, the PPHR2-51,-124-lacZ construct showed a significant difference in lacZ expression compared to the PPHR2-124-lacZ construct at pH 4 (P < 0.0015), suggesting that the −51 site in conjunction with the −124 site plays a role in basal transcription. At pH 8, the PPHR2-51,-124-lacZ construct did not have any significant repression compared to pH 4 levels. This was distinct from the −124 mutation alone, which retained twofold repression. These results suggest that the −51 site contributes to the pH-dependent regulation of PHR2. Finally, we found that the PPHR2-51,-124,-575-lacZ construct showed no significant differences compared to the PPHR2-51,-124-lacZ construct in either the wild-type or rim101−/− background regardless of pH. These results demonstrate that Rim101-dependent repression is conferred by the −51 and −124 sites alone and that the −575 site does not play a role in the Rim101- or pH-dependent regulation of PHR2.

The −124 site acts as a classical Rim101 binding site.

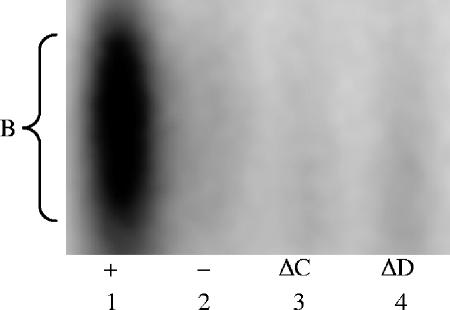

Based on the LacZ assays, the −124 Rim101 binding site is the primary site for pH- and Rim101-dependent expression. Interestingly, this site is both a classical and a divergent site (5′-TTCTTGGC). To determine if this site is acting as either a classical or a divergent site, we conducted EMSAs using mutations in nucleotides specific for either the classical (the C in position 8) or the divergent (the T in position 2) sites. Protein extracts from wild-type cells shifted the radiolabeled DNA fragment spanning the wild-type −124 site but not a mutated −124 site (Fig. 2 and 5, lanes 1 and 2). Importantly, protein extracts from wild-type cells were also unable to shift the DNA fragments containing a mutation in either the classical site (ΔC) or the divergent site (ΔD) (Fig. 5, lanes 3 and 4). Based on these results, nucleotides specific to both the classical and divergent sites of the −124 site are critical for Rim101 binding in vitro.

FIG. 5.

The −124 site acts as a classical and divergent Rim101 binding site by EMSA. Protein extracts from wild-type (DAY286) cells grown at pH 8 were incubated with DNA probes for the endogenous (+), the mutated (−), the classical-site mutated (ΔC), and the divergent-site mutated (ΔD) sequences of the −124 PHR2 site.

To further address this issue, we constructed the same site-specific mutations to disrupt either the classical or divergent binding sites in the PPHR2-lacZ construct to generate PPHR2-124ΔC-lacZ and PPHR2-124ΔD-lacZ, respectively. These constructs were introduced into the wild-type and rim101−/− backgrounds, and β-galactosidase activity was determined (Table 3). In wild-type cells at pH 4, mutation of either the classical or the divergent site reduced expression compared to the PPHR2-lacZ construct (P < 0.004 and P < 3 × 10−5, respectively), although the divergent site mutation had a greater reduction in expression, similar to that observed for the PPHR2-124-lacZ construct at pH 4. At pH 8, the classical-site mutation resulted in about fourfold repression compared to that at pH 4; the divergent-site mutation resulted in about eightfold repression. While mutation of the classical and divergent sites reduced pH-dependent repression compared to the PPHR2-lacZ construct, the classical site mutation had the greatest effect on pH-dependent repression. These results demonstrate that the C in position 8 of the −124 site, which specifies a classical Rim101 binding site, is important for pH-dependent expression.

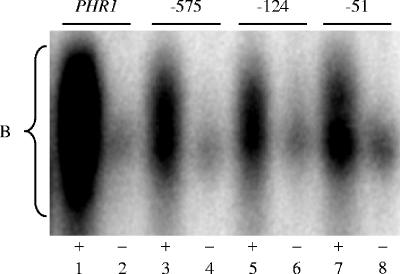

Rim101 processing is not required for DNA binding.

Previous studies, as well as those described above, demonstrated that Rim101 can bind to Rim101-dependent promoters (27). However, these analyses did not address whether Rim101 processing affects DNA binding. To address this question, EMSAs were conducted using protein extracts from a rim13−/− strain, which does not process Rim101 (19). Using whole-cell extracts from rim13−/− cells grown at pH 8, in the presence of the PHR1, PHR2 −575, PHR2 −124, or PHR2 −51 radiolabeled probes, a gel shift was observed (Fig. 6, lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7). However, in the presence of the PHR1, PHR2 −575, PHR2 −124, or PHR2 −51 radiolabeled probes containing a mutated Rim101 binding site, a dramatic reduction in gel shift was observed (Fig. 6, lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8). These results are similar to those observed for protein extracts from wild-type cells and demonstrate that full-length Rim101 can bind to the Rim101 binding site.

FIG. 6.

Rim101 processing is not required for DNA binding by EMSA. Protein extracts from rim13−/− + RIM101-V5 (DAY643) cells grown at pH 8 were incubated with radiolabeled DNA probes for the endogenous (+) (lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7) or mutated (−) (lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8) PHR1 promoter or PHR2 (−575, −124, and −51) promoters.

Environmental pH affects Rim101 binding activity.

Like other fungi, C. albicans Rim101 is processed to an active form at alkaline pH. However, unlike other fungi, it is also processed to a novel 65-kDa form at acidic pH (19). To determine if the 65-kDa processed form can bind promoters, we conducted EMSAs on wild-type cells grown at either alkaline or acidic pH. As observed previously, protein extracts from wild-type cells grown at pH 8 shifted the PHR1, PHR2 −575, PHR2 −124, and PHR2 −51 radiolabeled probes but not the mutated radiolabeled probes (Fig. 7A, lanes 9 to 16). Protein extracts from wild-type cells grown at pH 4 also shifted the PHR1, PHR2 −575, PHR2 −124, and PHR2 −51 radiolabeled probes (Fig. 7A, lanes 1 to 8), but surprisingly, there was a dramatic reduction in gel shift from cells grown at pH 4 compared to cells grown at pH 8 (for example, compare lanes 1 and 9 in Fig. 7A). The pH of the protein extracts following purification was not affected by the pH of the growth medium, demonstrating that these results are not due to a pH-dependent effect on protein-DNA complex formation for the EMSA. We also considered the possibility that there was less Rim101 protein from the cells grown at pH 4, compared to the cells grown at pH 8, that would account for this reduction in DNA binding activity. Thus, 250 μg of the protein extracts used for the EMSA was run on Western blots and probed using the anti-V5 antibody (Fig. 7A, lanes 17 and 18). While we observed slightly more Rim101 protein at pH 8 than at pH 4 (1.2-fold), this difference does not account for the fivefold decrease in DNA binding activity observed in cultures grown at pH 4 compared to cultures grown at pH 8. These results suggest the possibility that Rim101 may not be as competent to bind to the Rim101 binding site in promoters from cells grown at pH 4 compared to pH 8.

FIG. 7.

EMSAs show that Rim101 DNA binding ability is affected by environmental pH. Protein extracts from rim101−/− + RIM101-V5 (DAY492) (A) and rim13−/− + RIM101-V5 (DAY643) (B) cells grown at pH 4 (lanes 1 to 8) and pH 8 (lanes 9 to 16) were incubated with radiolabeled DNA probes for endogenous (+) PHR1 (lanes 1 and 9); mutated (−) PHR1 (lanes 2 and 10); endogenous (+) PHR2 at the −575 (lanes 3 and 11), −124 (lanes 5 and 13), and −51 (lanes 7 and 15) sites; or mutated (−) PHR2 at the −575 (lanes 4 and 12), −124 (lanes 6 and 14), and −51 (lanes 8 and 16) sites and analyzed by EMSA. Protein samples (250 μg) from rim101−/− + RIM101-V5 (A, lanes 17 and 18) and rim13−/− + RIM101-V5 (B, lanes 17 and 18) grown at pH 4 (lane 17) or pH 8 (lane 18) were analyzed by Western blotting. The 75-kDa molecular mass marker, full-length (FL) Rim101-V5, and processed (P1 and P2) Rim101-V5 are noted.

Since there are distinct processed forms of Rim101 at pH 4 and pH 8 (19), we considered the possibility that one or more of these forms may promote or inhibit the DNA binding activity. Since processing is not required for DNA binding activity in vitro (Fig. 6), we conducted EMSAs using protein extracts from rim13−/− cells, which express only the full-length form of Rim101 (19). Similar to the results described above, protein extracts from rim13−/− cells grown at pH 4 did shift the PHR1, PHR2 −575, PHR2 −124, and PHR2 −51 radiolabeled probes (Fig. 7B, lanes 1 to 8). However, the amount of probe shifted from cells grown at pH 4 was dramatically reduced compared to the amount shifted from cells grown at pH 8 (Fig. 7B, lanes 9 to 16). Furthermore, Western blot analyses of the rim13−/− protein extracts used for the EMSAs showed that comparable amounts of Rim101 protein were purified from the cultures grown at pH 4 and those grown at pH 8 (Fig. 7B, lanes 17 and 18). These results indicate that the difference between the Rim101 DNA binding activity observed at pH 4 compared to that observed at pH 8 is clearly not due to differences in Rim101 protein concentration. Furthermore, these results demonstrate that this pH-dependent DNA binding activity is not mediated by the different processed forms of Rim101. Thus, we infer that another factor, which is pH dependent, affects the ability of the Rim101 protein to interact with DNA.

DISCUSSION

The mechanism of Rim101/PacC transcriptional regulation has been the focus of studies of numerous fungi, including S. cerevisiae, A. nidulans, and C. albicans (6, 25). In A. nidulans, PacC acts directly as an activator of genes such as ipnA and as a repressor of genes such as gabA (11, 13). In S. cerevisiae, Rim101 has been shown only to act directly as a repressor of genes such as NRG1 and SMP1 (17). In C. albicans, Ramon and Fonzi previously demonstrated that Rim101 is a direct activator of PHR1 transcription (27). Based on the studies presented here, we demonstrate that C. albicans Rim101 can interact with PHR2 promoter elements, that this interaction requires the Rim101 binding site, and that these interactions are important in vivo. While we cannot rule out the possibility that Rim101 associates with these sites indirectly through an additional factor, the simplest model suggests that Rim101 is a direct repressor of PHR2 transcription. Thus, C. albicans Rim101 appears to act like A. nidulans PacC in that it clearly has both positive and negative transcriptional regulatory functions. Furthermore, we were able to demonstrate that endogenous Rim101 is capable of binding to promoters of alkaline-pH-induced genes, PHR1, and promoters of alkaline-pH-repressed genes, PHR2. We were also able to establish that Rim101 processing is not required for DNA binding, similar to results obtained for S. cerevisiae and A. nidulans (17, 24). However, in vivo, processing promotes PacC nuclear localization (21), and we expect this to also be the case for C. albicans.

The PHR2 promoter contains three sequences that are predicted classical or divergent Rim101 binding sites (13, 27). The most distal site, at position −575, is strictly a classical Rim101 binding site (5′-CTTGGC). We found that Rim101 could bind to this site in vitro; however, the −575 site is not required for pH-dependent regulation in vivo. Thus, Rim101 binding to the −575 site in vivo is neither necessary nor sufficient to repress PHR2 expression. The most proximal site, at position −51, is strictly a divergent Rim101 binding site (5′-CCAAGAA). We found that Rim101 could also bind to this site in vitro. However, in vivo studies demonstrated that while the −51 site is not required for pH-dependent regulation, it can play a role when the −124 site is mutated (see below).

The −124 site can specify both a classical and a divergent site (5′-TTCTTGGC), and this site binds Rim101 in vitro. However, unlike the −51 and −575 sites, the −124 site confers most of the pH-dependent regulation observed for PHR2. While the −124 site is required for PHR2 repression, there is still residual repression when the −124 site is mutated. This residual repression is now dependent on the −51 site, suggesting that this site may indeed be involved in PHR2 regulation in vivo.

In the absence of Rim101, the normally alkaline-pH-repressed PHR2 becomes an alkaline-pH-induced gene. Interestingly, we found that mutation of the −51 site, but not the −124 or the −575 site, impaired alkaline induction in the rim101−/− background. In all cases where the −51 site is intact, lacZ is induced more than twofold at alkaline pH in the rim101−/− background. However, in all cases where the −51 site is mutated, lacZ is induced less than twofold at alkaline pH in the rim101−/− background. One possibility is that this region of the PHR2 promoter is important for RNA polymerase binding or stability. However, lacZ expression at acidic pH is similar when driven from the PHR2 promoter containing an intact −51 site, a mutated −51 site, and the mutated −51 and −575 sites, suggesting that the −51 site is not required for general transcription. Thus, the −51 site may recruit a factor that promotes gene expression at alkaline pH in the absence of Rim101.

What is the Rim101 binding site? Previous work of Ramon and Fonzi, and work also described here, clearly demonstrates that C. albicans Rim101 does not require the first G of the classical site for binding (see Fig. 2, specifically, the PHR1 and the PHR2 −51 lanes). This is contrary to findings for A. nidulans, which demonstrated that any other nucleotide in the first position besides G resulted in markedly reduced GST-PacC binding (13). However, in C. albicans, the requirement for a G in this position is binding site dependent. For the PHR1 Rim101 binding site and the PHR2 −51 site, there is no G in the first position, yet Rim101 binds to these sites in vitro, and these sites are relevant in vivo. However, for the PHR2 −124 site, there is a G in the first position that is essential for Rim101 binding in vitro and important for repression in vivo. Computer analysis of promoters from Rim101-dependent alkaline-pH-induced genes identified the consensus sequence GCCAAGAA, supporting the idea that the first G is often important for Rim101-dependent regulation (4). Thus, we propose that, in general, the Rim101 binding site can be considered GCCAAGAA, although divergence from this site can be tolerated. Support for this idea comes from A. nidulans. For example, the A in position 5 of the PacC site is frequently a G (5′-GCCAGG), although this results in lower-affinity binding (12). Furthermore, in the gabA promoter, the A in position 4 can be changed with no apparent effect on PacC binding (11); however, in the ipnA promoter, the A in position 4 is essential for PacC binding (29). Finally, our EMSAs revealed that Rim101 binds more efficiently to the Rim101 binding site of the PHR1 promoter than to any of the PHR2 binding sites, including the −51 and −124 sites, which share the CCAAGAA sequence. This result is supported by competition studies (unpublished data). Thus, we suggest that the ability of Rim101 to bind to the consensus sequence GCCAAGAA is context dependent.

Why is the −575 site dispensable for Rim101-mediated PHR2 regulation? One possibility is that the orientation of the binding site is important for Rim101-dependent regulation. This does not seem likely, since the −124 site, which plays the major role in PHR2 repression, is in the same orientation as the −575 site. Another possibility is that this site is too far away from the transcriptional start site. In the case of the PHR1 promoter, the Rim101 binding sites are located at positions −516 and −825. Thus, the distance from the transcriptional start site does not appear to be a sufficient explanation. However, if Rim101 repression is mediated by inhibiting the binding of an activator, then binding site location is critical. In A. nidulans, expression of gabA is governed by the transcriptional activator IntA (3). However, gabA is repressed at alkaline pH in a PacC-dependent manner. Repression occurs because the PacC binding sites overlap with the IntA binding site (11). At alkaline pH, PacC is active and binds to the gabA promoter, which excludes IntA from binding to its site. Thus, we propose that a similar mechanism may occur in C. albicans PHR2 Rim101-dependent repression. Support for this model comes from the fact that in the absence of Rim101, PHR2 becomes an alkaline-pH-induced gene, suggesting that additional factors are at play.

Our results strongly suggest the existence of additional regulatory factors that govern PHR2 expression. First, as stated above, PHR2 becomes an alkaline-pH-induced gene in the absence of Rim101. If Rim101 were the only factor involved in expression, then PHR2 should be expressed similarly at acidic and alkaline pHs. This additional regulatory control does not appear to be PHR2 specific, as several genes repressed at alkaline pH in a Rim101-dependent manner become alkaline induced in the absence of Rim101 (4). Second, from our EMSAs, we have found at least one additional DNA-protein complex that results in a band that we refer to as band A (see Fig. 2, for example). While this band may be a nonspecific artifact, it appears that the −51 site was not as efficiently shifted to band A compared to the PHR1 binding site or the PHR2 −124 and −575 sites, suggesting some specificity in binding (Fig. 4). For example, all of the sequences that are shifted to band A also contain an uninterrupted stretch of eight to nine A residues, whereas the longest run of As in the −51 site is three residues.

Finally, we found that Rim101 binding to DNA is dependent on the pH in which the cells were grown. This pH-dependent binding was not an attribute of processing, as Rim101 isolated from rim13−/− cells was able to efficiently bind to the Rim101 binding site when isolated from cells grown at alkaline pH but not when isolated from cells grown at acidic pH. Thus, we propose that at acidic pH, Rim101 binding activity is inhibited by an as-yet-unidentified factor or that at alkaline pH, Rim101 binding activity is promoted by an unidentified factor. Regardless, we are unaware of any previous descriptions of Rim101 regulation except for the well-described proteolytic processing. Thus, in addition to proteolytic activation, C. albicans appears to have at least one additional mechanism to regulate Rim101 activity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Uhl and Alexander Johnson for providing plasmid pAU36. We thank Amy Kullas, Julie Wolf, and Lucia Zacchi for critical reading of the manuscript. Dana A. Davis thanks Debra L. McWilliam for continued support during the course of this work.

This work of Dana A. Davis is supported by NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease award 1R01-AI064054-01 and by the Investigators in Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, A., D. E. Gotschling, C. A. Kaiser, and T. Stearns. 1997. Methods in yeast genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 2.Arechiga-Carvajal, E. T., and J. Ruiz-Herrera. 2005. The RIM101/pacC homologue from the basidiomycete Ustilago maydis is functional in multiple pH-sensitive phenomena. Eukaryot. Cell 4:999-1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey, C. R., H. A. Penfold, and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1979. cis-dominant regulatory mutations affecting the expression of GABA permease in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 169:79-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bensen, E. S., S. J. Martin, M. Li, J. Berman, and D. A. Davis. 2004. Transcriptional profiling in C. albicans reveals new adaptive responses to extracellular pH and functions for Rim101p. Mol. Microbiol. 54:1335-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bignell, E., S. Negrete-Urtasun, A. M. Calcagno, H. N. Arst, Jr., T. Rogers, and K. Haynes. 2005. Virulence comparisons of Aspergillus nidulans mutants are confounded by the inflammatory response of p47phox−/− mice. Infect. Immun. 73:5204-5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis, D. 2003. Adaptation to environmental pH in Candida albicans and its relation to pathogenesis. Curr. Genet. 44:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis, D., J. E. Edwards, Jr., A. P. Mitchell, and A. S. Ibrahim. 2000. Candida albicans RIM101 pH response pathway is required for host-pathogen interactions. Infect. Immun. 68:5953-5959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis, D., R. B. Wilson, and A. P. Mitchell. 2000. RIM101-dependent and -independent pathways govern pH responses in Candida albicans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:971-978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis, D. A., V. M. Bruno, L. Loza, S. G. Filler, and A. P. Mitchell. 2002. Candida albicans Mds3p, a conserved regulator of pH responses and virulence identified through insertional mutagenesis. Genetics 162:1573-1581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denison, S. H., M. Orejas, and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1995. Signaling of ambient pH in Aspergillus involves a cysteine protease. J. Biol. Chem. 270:28519-28522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espeso, E. A., and H. N. Arst, Jr. 2000. On the mechanism by which alkaline pH prevents expression of an acid-expressed gene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:3355-3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Espeso, E. A., and M. A. Penalva. 1996. Three binding sites for the Aspergillus nidulans PacC zinc-finger transcription factor are necessary and sufficient for regulation by ambient pH of the isopenicillin N synthase gene promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 271:28825-28830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Espeso, E. A., J. Tilburn, L. Sanchez-Pulido, C. V. Brown, A. Valencia, H. N. Arst, Jr., and M. A. Penalva. 1997. Specific DNA recognition by the Aspergillus nidulans three zinc finger transcription factor PacC. J. Mol. Biol. 274:466-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fonzi, W. A. 1999. PHR1 and PHR2 of Candida albicans encode putative glycosidases required for proper cross-linking of β-1,3- and β-1,6-glucans. J. Bacteriol. 181:7070-7079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Futai, E., T. Maeda, H. Sorimachi, K. Kitamoto, S. Ishiura, and K. Suzuki. 1999. The protease activity of a calpain-like cysteine protease in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for alkaline adaptation and sporulation. Mol. Gen. Genet. 260:559-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kullas, A. L., M. Li, and D. A. Davis. 2004. Snf7p, a component of the ESCRT-III protein complex, is an upstream member of the RIM101 pathway in Candida albicans. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1609-1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamb, T. M., and A. P. Mitchell. 2003. The transcription factor Rim101p governs ion tolerance and cell differentiation by direct repression of the regulatory genes NRG1 and SMP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:677-686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb, T. M., W. Xu, A. Diamond, and A. P. Mitchell. 2001. Alkaline response genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their relationship to the RIM101 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276:1850-1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li, M., S. J. Martin, V. M. Bruno, A. P. Mitchell, and D. A. Davis. 2004. Candida albicans Rim13p, a protease required for Rim101p processing at acidic and alkaline pHs. Eukaryot. Cell 3:741-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maccheroni, W., Jr., G. S. May, N. M. Martinez-Rossi, and A. Rossi. 1997. The sequence of palF, an environmental pH response gene in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 194:163-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mingot, J. M., E. A. Espeso, E. Diez, and M. A. Penalva. 2001. Ambient pH signaling regulates nuclear localization of the Aspergillus nidulans PacC transcription factor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1688-1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muhlrad, D., R. Hunter, and R. Parker. 1992. A rapid method for localized mutagenesis of yeast genes. Yeast 8:79-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muhlschlegel, F. A., and W. A. Fonzi. 1997. PHR2 of Candida albicans encodes a functional homolog of the pH-regulated gene PHR1 with an inverted pattern of pH-dependent expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:5960-5967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orejas, M., E. A. Espeso, J. Tilburn, S. Sarkar, H. N. Arst, Jr., and M. A. Penalva. 1995. Activation of the Aspergillus PacC transcription factor in response to alkaline ambient pH requires proteolysis of the carboxy-terminal moiety. Genes Dev. 9:1622-1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peñalva, M. A., and H. N. Arst, Jr. 2002. Regulation of gene expression by ambient pH in filamentous fungi and yeasts. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:426-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porta, A., A. M. Ramon, and W. A. Fonzi. 1999. PRR1, a homolog of Aspergillus nidulans palF, controls pH-dependent gene expression and filamentation in Candida albicans. J. Bacteriol. 181:7516-7523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramon, A. M., and W. A. Fonzi. 2003. Diverged binding specificity of Rim101p, the Candida albicans ortholog of PacC. Eukaryot. Cell 2:718-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramon, A. M., A. Porta, and W. A. Fonzi. 1999. Effect of environmental pH on morphological development of Candida albicans is mediated via the PacC-related transcription factor encoded by PRR2. J. Bacteriol. 181:7524-7530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tilburn, J., S. Sarkar, D. A. Widdick, E. A. Espeso, M. Orejas, J. Mungroo, M. A. Penalva, and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1995. The Aspergillus PacC zinc finger transcription factor mediates regulation of both acid- and alkaline-expressed genes by ambient pH. EMBO J. 14:779-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uhl, M. A., and A. D. Johnson. 2001. Development of Streptococcus thermophilus lacZ as a reporter gene for Candida albicans. Microbiology 147:1189-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson, R. B., D. Davis, B. M. Enloe, and A. P. Mitchell. 2000. A recyclable Candida albicans URA3 cassette for PCR product-directed gene disruptions. Yeast 16:65-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson, R. B., D. Davis, and A. P. Mitchell. 1999. Rapid hypothesis testing in Candida albicans through gene disruption with short homology regions. J. Bacteriol. 181:1868-1874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu, W., and A. P. Mitchell. 2001. Yeast PalA/AIP1/Alix homolog Rim20p associates with a PEST-like region and is required for its proteolytic cleavage. J. Bacteriol. 183:6917-6923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu, W., F. J. Smith, Jr., R. Subaran, and A. P. Mitchell. 2004. Multivesicular body-ESCRT components function in pH response regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Candida albicans. Mol. Biol. Cell 15:5528-5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]